User:Pluginfile/sandbox

Attraction and Pheromones

[edit]Pheromones

[edit]Pheromones, derived from the Greek words 'pherein' (to transfer) and 'hormon' (to excite), are chemical substances secreted by animals to facilitate communication within their species.[1] These signals are crucial in mating, territorial marking, and social organization. For example, ants use pheromones to establish trails leading to food sources, enabling efficient foraging, while mammals emit pheromones to signal readiness and attract potential mates. Pheromones are detected through specialized sensory structures, such as the vomeronasal organ or olfactory receptors, which trigger specific behavioural or physiological responses.[2] Beyond animals, research has explored the potential role of pheromones in humans, with studies suggesting they may influence subconscious social and reproductive behaviours. However, this remains a subject of scientific debate.[3]

Controversies surrounding Pheromones

[edit]In humans, the role of pheromones is more contentious. Unlike in other species, where pheromonal effects are evident and reproducible, evidence for human pheromones is less definitive. Chemicals such as Androstadiene and Estratetraenol have been proposed as potential human pheromones, with studies suggesting they may subtly influence mood, interpersonal attraction, and social interactions.[4] However, these findings are often debated, as critics argue that the observed effects could be more consistent, culturally mediated, or more substantial to qualify as accurate pheromonal communication. Furthermore, human behaviour is influenced by a wide array of cognitive, cultural, and environmental factors, complicating the isolation of pheromonal effects.[5] Recent advances in research methods, including brain imaging and highly sensitive chemical detection techniques, have provided new insights into how pheromones may function in humans and other species. Collectively, experiments have primarily explored three potential categories of human pheromones such as axillary steroids, vaginal aliphatic acids, and compounds that activate the vomeronasal organs.[6] For example, a 2018 study suggested that specific pheromones influence social psychology as it explores the intersection of men's sexual perception and cognitive responses.[7]

Pheromones and Interpersonal Attraction

[edit]Attraction

[edit]Attraction is characterized by being drawn to another person, influenced by a combination of factors, including physical appearance, communication, and scent.[8] Pheromones are hypothesized to play a subtle role in this process, potentially affecting perceptions and emotions at a subconscious level. These chemical signals are thought to interact with the brain's emotional and sexual centres, possibly through the olfactory system. While humans lack a fully functional vomeronasal organ (VNO), a structure used by many animals to detect pheromones, the sense of smell remains an important component of human attraction.

Research suggests that pheromones may influence perceptions of attractiveness and compatibility. Certain scents are believed to evoke positive emotional responses or signal genetic compatibility, which could promote deeper social or romantic connections.[9] However, the extent to which pheromones affect human attraction has yet to be fully understood and remains a topic of scientific debate.

Chemicals linked to human pheromones

[edit]Research has focused on two substances often associated with pheromone-like effects in humans[10]:

- Androstadiene is found in male sweets. It has improved women's mood and heightened their perception of men.

- Estratetraenol, a compound present in female secretions, appears to have a similar effect on men, subtly enhancing their mood and attraction.

While the influence of these substances is less pronounced than the pheromone-driven behaviours observed in animals, studies suggest they play a role in shaping social and romantic perceptions.[11] For instance, exposure to androstadiene in a man's body odour may elevate a woman's mood or increase her focus during interactions, contributing to a more positive social experience and potentially fostering attraction.

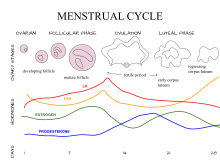

Scent preference and the Menstrual cycle

[edit]Studies have shown that a woman's scent preferences may vary according to her menstrual cycle.[12] During ovulation, when fertility is at its peak, women are more likely to prefer the scent of men with symmetrical facial features and immune system genes that differ from their own. The Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) typically measures these immune system genes. This preference is an evolutionary strategy aimed at increasing genetic diversity in offspring, thereby enhancing their health and survival prospects.

While the role of pheromones in this process remains debatable, the findings underscore the significance of olfactory cues in human attraction and reproduction. The interplay between biology and behaviour is particularly evident here, as subconscious chemical signals may subtly influence mate selection.[13] Although cultural and social factors often overshadow these biological mechanisms, their potential impact on human behaviour continues to be a focus of scientific research.

Pheromones in Group Behaviour

[edit]Menstrual Synchrony

[edit]

Menstrual synchrony is a contested phenomenon suggesting that women who spend significant time together may experience alignment in their menstrual cycles, potentially mediated by pheromonal communication. First proposed by Martha McClintock in 1971, this hypothesis has been the subject of extensive research and debate for decades.[14]

Proponents of the theory argue that pheromones released by women could influence the hormonal cycles of others in proximity, fostering biological synchrony. This synchrony may have had evolutionary benefits, such as promoting social cohesion and cooperative childcare in ancestral environments. However, more recent studies have challenged these findings, proposing that the observed alignment of menstrual cycles could result from statistical chance, shared environmental conditions, or other non-pheromonal factors.

Social Mood Contagion

[edit]Pheromones may influence group dynamics by subtly shaping emotional states, contributing to social mood contagion. Stress-related pheromones, released in sweat, are hypothesized to evoke similar stress responses in others within a group.[15] This synchronization of emotional states enhances group cohesion during challenging situations, such as those requiring teamwork, defence, or coordinated action. Evolutionarily, such mechanisms provided adaptive advantages, fostering collaboration and mutual support in early human or primate societies.

Human Alarm Pheromone

[edit]An alarm pheromone is a chemical signal released by an individual that communicates potential danger to others of the same conspecifics. While well-documented in many mammals, evidence for human alarm pheromones remained largely theoretical until the early 21st century.

Biological evidence for pheromonal mood contagion in humans comes from neuro-imaging studies suggesting that exposure to stress-related compounds through olfactory epithelium can activate the brain's emotional centres, such as the amygdala, leading to corresponding changes in mood. Research conducted in 2008 used functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) to measure acute emotional stress. The result demonstrates that sweat collected from individuals during their first skydiving experience triggered significant activation in the left amygdala of unrelated individuals compared to sweat collected during physical exercise.[16] Results from the behavioural experiments revealed that participants exposed to stress-induced sweat showed a 43% improvement in distinguishing between neutral and threatening facial expressions compared to those exposed to exercise-induced sweat. This enhanced discrimination suggests a role for alarm pheromones in sharpening threat evaluation during social interactions. [16]

While previous studies indicated that individuals could distinguish stress-induced sweat from neutral sweat based on odour, this study confirmed that participants could not consciously differentiate between the two regarding intensity or qualitative odour properties. These findings suggest that the observed effects operate subconsciously and are not directly linked to odour perception. The results support the hypothesis that stress signals can be transmitted through chemosensory cues, even without conscious awareness of the 'smell or fear'. This research expands the understanding of human chemosensory communication and its broader implications for emotional and social behaviour.[17]

Social Psychology, Culture, and Pheromones

[edit]Cultural Views on Scent and Attraction

Cultural norms significantly shape how people perceive the role of scent in attraction. In some societies, natural body odours are considered desirable and an essential part of intimacy, while in others, there is a strong emphasis on masking natural scents with perfumes and deodorants. These cultural differences highlight the interaction between biological factors, like pheromones, and social constructs.

For example, in Western cultures, personal grooming products are often marketed as essential for social and romantic success.[18] This emphasis on artificial scents may overshadow or alter individuals' natural pheromonal signals. Conversely, pheromonal communication may be more prominent in attraction and social bonding in cultures where natural body odour is embraced.

The Role of Scent in Attraction

[edit]

Wedekind's T-shirt study

[edit]Claus Wedekind conducted a study in 1995 exploring the role of scent in attraction, which has been widely referenced in research on human mate selection. In this experiment, men were asked to wear the same T-shirt for two consecutive nights, avoiding scented products, alcohol, or spicy foods to ensure their natural body odour remained unaltered. Women were then asked to smell the shirts and rate their attractiveness based on scent alone.[19] The findings revealed that women preferred the scent of men whose Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) genes differed. MHC gene diversity is associated with more muscular immune systems in offspring, suggesting an evolutionary advantage in selecting genetically complementary partners.[20]

Wedekind's study is often cited as foundational in understanding the relationship between scent and mate selection. It provided compelling evidence that subconscious olfactory cues may influence human attraction, possibly through pheromones or other chemical signals. However, the study's methodology has been scrutinized, with critics highlighting potential limitations such as its relatively small sample size and the influence of cultural or environmental factors. Subsequent research has yielded mixed results, with some studies replicating the findings and others questioning the universality of scent-based preferences.

The implications of Wedekind's findings extend beyond evolutionary biology, informing research in social psychology and even the fragrance industry, where natural scent preferences are increasingly considered in product development. Despite ongoing debates about whether pheromones or other factors mediate these effects, the study remains a pivotal example of how biological cues can subtly shape human social and reproductive behaviour.

Sexual Attraction

[edit]

Research suggests that pheromones may play a role in sexual attraction and romantic compatibility. Experiments have shown that exposure to pheromonal compounds, such as androstadiene and estratetraenol, can make participants feel positive or open to social engagement.

Axillary sweet, often associated with pheromonal communication, appears less directly linked to immediate attraction but may have an indirect role. An experimental study conducted in 2016 found that men wearing fragranced antiperspirants were perceived as more attractive to women than those using unscented products. These findings suggest that while axillary sweat may not always be inherently appealing, it supports the hypothesis of its connection to immunogenetics.[21] Research has indicated a strong relationship between an individual's MHC genotype and their preferences for perfumes that they thought reflected themselves.[22] This suggests that certain fragrances amplify body odours in a way that signals genetic compatibility, thereby influencing mate preferences.

Challenges

[edit]While studies have shown some correlation between pheromones and social behaviours, there is no definitive cause-effect evidence demonstrating the functional role of human pheromones. Many experiments need more sensitivity analyses or rely on limited criteria, raising questions about the validity and generalizability of their findings. Additionally, isolating the effects of pheromones from other influential factors such as cultural norms, environmental conditions, and individual preferences remains a significant challenge, as these elements heavily shape behaviour and perception.

The concept of pheromones has also been widely commercialized, particularly by the fragrance industry. Many perfumes and colognes are marketed as containing synthetic pheromones, claimed to enhance attractiveness and influence interpersonal relationships. However, the scientific basis for these claims is often dubious, and evidence supporting the effectiveness of such products remains limited. Nonetheless, the enduring popularity of these fragrances reflects a broader belief in the power of scent to shape social interactions and relationships.

Despite these challenges and controversies, research on human pheromones continues to evolve. A growing area of interest focuses on how pheromones might provide insights into biological processes, such as immune system functioning. While the precise role of pheromones in human behaviour remains unclear, ongoing studies may uncover new perspectives on the complex interplay between chemical signalling, health, and social dynamics.

References

[edit]- ^ Karlson, P.; Lüscher, M. (1959-01). "'Pheromones': a New Term for a Class of Biologically Active Substances". Nature. 183 (4653): 55–56. doi:10.1038/183055a0. ISSN 1476-4687.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Dulac, Catherine; Torello, A. Thomas (2003-07). "Molecular detection of pheromone signals in mammals: from genes to behaviour". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 4 (7): 551–562. doi:10.1038/nrn1140. ISSN 1471-003X.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Monti-Bloch, L.; Grosser, B.I. (1991-10). "Effect of putative pheromones on the electrical activity of the human vomeronasal organ and olfactory epithelium". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 39 (4): 573–582. doi:10.1016/0960-0760(91)90255-4. ISSN 0960-0760.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Huoviala, Paavo; Rantala, Markus J. (2013-05-22). "A Putative Human Pheromone, Androstadienone, Increases Cooperation between Men". PLoS ONE. 8 (5): e62499. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062499. ISSN 1932-6203.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ St John, Freya A. V.; Edwards-Jones, Gareth; Jones, Julia P. G. (2010). "Conservation and human behaviour: lessons from social psychology". Wildlife Research. 37 (8): 658. doi:10.1071/wr10032. ISSN 1035-3712.

- ^ Hays, Warren S. T. (2003-04-30). "Human pheromones: have they been demonstrated?". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 54 (2): 89–97. doi:10.1007/s00265-003-0613-4. ISSN 0340-5443.

- ^ Oren, Chen; Peled-Avron, Leehe; Shamay-Tsoory, Simone G (2019-07). "A scent of romance: human putative pheromone affects men's sexual cognition". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 14 (7): 719–726. doi:10.1093/scan/nsz051. ISSN 1749-5024.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Byrne, Donn (1969), "Attitudes and Attraction", Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Elsevier, pp. 35–89, retrieved 2024-12-15

- ^ Grammer, Karl; Fink, Bernhard; Neave, Nick (2005-02). "Human pheromones and sexual attraction". European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 118 (2): 135–142. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.08.010. ISSN 0301-2115.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Grosser, Bernard I; Monti-Bloch, Louis; Jennings-White, Clive; Berliner, David L (2000-04). "Behavioral and electrophysiological effects of androstadienone, a human pheromone". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 25 (3): 289–299. doi:10.1016/s0306-4530(99)00056-6. ISSN 0306-4530.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Oren, Chen; Peled-Avron, Leehe; Shamay-Tsoory, Simone G (2019-07). "A scent of romance: human putative pheromone affects men's sexual cognition". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 14 (7): 719–726. doi:10.1093/scan/nsz051. ISSN 1749-5024.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Facts, Views and Vision in ObGyn. 14 (3). 2022-09. doi:10.52054/fvvo.14.3. ISSN 2684-4230 https://doi.org/10.52054/fvvo.14.3.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Roelofs, W L (1995-01-03). "Chemistry of sex attraction". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 92 (1): 44–49. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.1.44. PMC 42814. PMID 7816846.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ MCCLINTOCK, MARTHA K. (1971-01-22). "Menstrual Synchrony and Suppression". Nature. 229 (5282): 244–245. doi:10.1038/229244a0. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Hatfield, Elaine; Cacioppo, John T.; Rapson, Richard L. (1993-06). "Emotional Contagion". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2 (3): 96–100. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.ep10770953. ISSN 0963-7214.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Mujica-Parodi, Lilianne; Strey, Helmut; Frederick, Blaise; Savoy, Robert; Cox, David; Botanov, Yevgeny; Tolkunov, Denis; Rubin, Denis; Weber, Jochen (2008-11-25). "Second-Hand Stress: Neurobiological Evidence for a Human Alarm Pheromone". Nature Precedings. doi:10.1038/npre.2008.2561.1. ISSN 1756-0357.

- ^ Masuo, Yoshinori; Satou, Tadaaki; Takemoto, Hiroaki; Koike, Kazuo (2021-04-28). "Smell and Stress Response in the Brain: Review of the Connection between Chemistry and Neuropharmacology". Molecules. 26 (9): 2571. doi:10.3390/molecules26092571. ISSN 1420-3049.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Thein-Lemelson, Seinenu M. (2015). "Grooming and cultural socialization: A mixed method study of caregiving practices in Burma (Myanmar) and the United States". International Journal of Psychology. 50 (1): 37–46. doi:10.1002/ijop.12119. ISSN 1464-066X. PMC 4320772. PMID 25530498.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Wedekind, Claus; Füri, Sandra (1997-10-22). "Body odour preferences in men and women: do they aim for specific MHC combinations or simply heterozygosity?". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 264 (1387): 1471–1479. doi:10.1098/rspb.1997.0204. ISSN 0962-8452.

- ^ Wedekind, Claus; Penn, Dustin (2000-09-01). "MHC genes, body odours, and odour preferences". Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 15 (9): 1269–1271. doi:10.1093/ndt/15.9.1269. ISSN 0931-0509.

- ^ Allen, Caroline; Cobey, Kelly D.; Havlíček, Jan; Roberts, S. Craig (2016-11). "The impact of artificial fragrances on the assessment of mate quality cues in body odor". Evolution and Human Behavior. 37 (6): 481–489. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2016.05.001. ISSN 1090-5138.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Milinski, M. (2001-03-01). "Evidence for MHC-correlated perfume preferences in humans". Behavioral Ecology. 12 (2): 140–149. doi:10.1093/beheco/12.2.140. ISSN 1465-7279.