History of Apple Inc.

Apple Inc., originally Apple Computer, Inc., is a multinational corporation that creates and markets consumer electronics and attendant computer software, and is a digital distributor of media content. Apple's core product lines are the iPhone smartphone, iPad tablet computer, and the Mac personal computer. The company offers its products online and has a chain of retail stores known as Apple Stores. Founders Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, and Ronald Wayne created Apple Computer Co. on April 1, 1976, to market Wozniak's Apple I desktop computer,[2] and Jobs and Wozniak incorporated the company on January 3, 1977,[3] in Cupertino, California.

For more than three decades, Apple Computer was predominantly a manufacturer of personal computers, including the Apple II, Macintosh, and Power Mac lines, but it faced rocky sales and low market share during the 1990s. Jobs, who had been ousted from the company in 1985, returned to Apple in 1997 after his company NeXT was bought by Apple.[4] The following year he became the company's interim CEO,[5] which later became permanent.[6] Jobs subsequently instilled a new corporate philosophy of recognizable products and simple design, starting with the original iMac in 1998.

With the introduction of the successful iPod music player in 2001 and iTunes Music Store in 2003, Apple established itself as a leader in the consumer electronics and media sales industries, leading it to drop "Computer" from the company's name in 2007. The company is also known for its iOS range of smartphone, media player, and tablet computer products that began with the iPhone, followed by the iPod Touch and then iPad. As of June 30, 2015, Apple was the largest publicly traded corporation in the world by market capitalization,[7] with an estimated value of US$1 trillion as of August 2, 2018.[8] Apple's worldwide annual revenue in 2010 totaled US$65 billion, growing to US$127.8 billion in 2011[9] and $156 billion in 2012.[10]

1971–1985: Jobs and Wozniak

[edit]Pre-foundation

[edit]

Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, referred to collectively as "the two Steves", first met in mid-1971, when their mutual friend Bill Fernandez introduced then 21-year-old Wozniak to 16-year-old Jobs.[11][12] Their first business partnership began in the fall of that year when Wozniak, a self-educated electronics engineer, read an article in Esquire magazine that described a device that could place free long-distance phone calls by emitting specific tone chirps. Wozniak started to build his original “blue boxes”, which he tested by calling the Vatican City pretending to be Henry Kissinger wanting to speak to the pope.[13] Jobs managed to sell some two hundred blue boxes for $150 each, and split the profit with Wozniak.[11][12] Jobs later told his biographer that if it hadn't been for Wozniak's blue boxes, "there wouldn't have been an Apple."[14]

By 1972, Jobs had withdrawn from Reed College and Wozniak from UC Berkeley. Wozniak designed a video terminal that he could use to log on to the minicomputers at Call Computer. Alex Kamradt commissioned the design and sold a small number of them through his firm. Aside from their interest in up-to-date technology, the impetus for the two Steves seems to have had another source. In his essay From Satori to Silicon Valley (published 1986), cultural historian Theodore Roszak made the point that Apple Computer emerged from within the West Coast counterculture and the need to produce print-outs, letter labels, and databases. Roszak offers a bit of background on the development of the two Steves' prototype models.

In 1975, the two Steves started attending meetings of the Homebrew Computer Club.[15] New microcomputers such as the Altair 8800 and the IMSAI 8080 inspired Wozniak to build a microprocessor into his video terminal circuit to make a complete computer. At the time the only microcomputer CPUs generally available were the $179 Intel 8080 (equivalent to $1,014 in 2023), and the $170 Motorola 6800 (equivalent to $963 in 2023). Wozniak preferred the 6800, but both were out of his price range. So he watched, and learned, and designed computers on paper, waiting for the day he could afford a CPU.

When MOS Technology released its $20 (equivalent to $107 in 2023) 6502 chip in 1976, Wozniak wrote a version of BASIC for it, then began to design a computer for it to run on. The 6502 was designed by the same people who designed the 6800, as many in Silicon Valley left employers to form their own companies. Wozniak's earlier 6800 paper-computer needed only minor changes to run on the new chip.

By March 1, 1976, Wozniak completed the machine and took it to a Homebrew Computer Club meeting to show it off.[16] When Jobs saw Wozniak's computer, which later became the Apple I, he was immediately interested in its commercial potential.[17] Initially, Wozniak intended to share schematics of the machine for free, but Jobs insisted that they should instead build and sell bare printed circuit boards for the computer.[18] Wozniak originally offered the design to Hewlett-Packard (HP), where he worked at the time, but was denied by the company on five occasions.[19] Jobs eventually convinced Wozniak to go into business together and start a new company of their own.[20] In order to raise the money they needed to produce the first batch of printed circuit boards, Jobs sold his Volkswagen Type 2 minibus for $1,500, and Wozniak his HP-65 programmable calculator for $500.[18][16][21][22]

Apple I and company formation

[edit]

On April 1, 1976, Apple Computer Company was founded by Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, and Ronald Wayne.[25][20] The company was registered as a California business partnership.[26] Wayne, who worked at Atari, Inc. as a chief draftsman, became a co-founder in return for a 10% stake.[27][20][2] Wayne was gun-shy due to the failure of his own venture four years earlier. On April 12, less than two weeks after the company's formation, Wayne left Apple, selling his 10% share back to the two Steves for $800.[28][29]

According to Wozniak, Jobs proposed the name “Apple Computer” when he had just come back from Robert Friedland's All-One Farm in Oregon.[29] Jobs told Walter Isaacson that he was "on one of my fruitarian diets," when he conceived of the name and thought "it sounded fun, spirited and not intimidating ... plus, it would get us ahead of Atari in the phone book."[30]

The two Steves made a last trip to the Homebrew Computer Club and demonstrated the Apple I (AKA: The Apple Computer).[31] Paul Terrell, who operated the computer store chain Byte Shop, was impressed,[27] and gave the two Steves his card, asking them to keep in touch.[32] The next day, Jobs visited Terrell at the Mountain View Byte Shop store, and tried to sell him the bare circuit boards for the Apple I.[29] Terrell said he was only interested in purchasing the machine fully assembled, and that he would order 50 assembled computers and pay US$500 each on delivery (equivalent to $2,700 in 2023).[33][34][27] Jobs took the purchase order from the Byte Shop to national electronic parts distributor Cramer Electronics, and ordered the components needed. When asked by the credit manager how he would pay for the parts, Jobs replied, "I have this purchase order from the Byte Shop chain of computer stores for 50 of my computers and the payment terms are COD. If you give me the parts on net 30-day terms I can build and deliver the computers in that time frame, collect my money from Terrell at the Byte Shop and pay you."[35][36]

To verify the purchase order, the credit manager called Paul Terrell, who assured him if the computers showed up, Jobs would have more than enough money for the parts order. The two Steves and their small crew spent day and night building and testing the computers, and delivered to Terrell on time. Terrell was surprised to receive a batch of assembled circuit boards, as he had expected complete computers with a case, monitor and keyboard.[37][38] Nonetheless, he kept his word and paid the two Steves the money promised.[39][37][38][40]

The Apple I went on sale in July 1976 as an assembled circuit board with a retail price of $666.66.[41][42][43] Wozniak later said he had had no idea about the relation between the number and the mark of the beast, and that he came up with the price because he liked repeating digits.[39] About 200 units of the Apple I were eventually sold.[44]

The Apple I computer had some notable features, including the use of a TV display, whereas many machines had no display at all. This was not like the displays of later machines; the text was displayed at 60 characters per second – still faster than the teleprinters of contemporary machines of that era. The machine had bootstrap code on ROM, making it easier to start up. At the insistence of Paul Terrell, Wozniak designed a cassette interface for loading and saving programs, at the then-rapid pace of 1200 bit/s. The simple machine was a masterpiece of design using far fewer parts than anything in its class, and earned Wozniak his reputation as a designer.

Jobs looked for investments to expand the business,[38] but banks were reluctant to lend him money; the idea of a computer for ordinary people seemed absurd at the time. In August 1976, Jobs approached his former boss at Atari, Nolan Bushnell, who recommended that he meet with Don Valentine, the founder of Sequoia Capital.[38] Valentine was not interested in funding Apple, but in turn introduced Jobs to Mike Markkula, a millionaire who had worked under him at Fairchild Semiconductor.[38] Markkula saw great potential in the two Steves, and became an angel investor of their company.[45] He invested $92,000 in Apple out of his own property while securing a $250,000 (equivalent to $1,340,000 in 2023) line of credit from Bank of America.[45][38] In return, Markkula received a one-third stake in Apple.[45] Apple Computer, Inc. was incorporated on January 3, 1977.[38] The new corporation bought out the partnership the two Steves had formed nine months earlier.[46]

In February 1977, Markkula recruited Michael Scott from National Semiconductor to serve as the first president and CEO of Apple Computer, as the two Steves were both insufficiently experienced and he was not interested in taking that position himself.[47][48] That same month, Wozniak resigned from his job at Hewlett-Packard to work full-time for Apple.[46][49]

Apple II

[edit]Almost as soon as Apple had started selling its first computers, Wozniak moved on from the Apple I and began designing a greatly improved computer: the Apple II.[45] Wozniak completed a working prototype of the new machine by August 1976.[38][50] The two Steves presented the Apple II computer to the public at the first West Coast Computer Faire on April 16 and 17, 1977. On the first day of the exhibition, Jobs introduced the Apple II to a Japanese chemist named Toshio Mizushima, who became the first authorized Apple dealer in Japan. In the May 1977 issue of Byte, Wozniak said of the Apple II design, "To me, a personal computer should be small, reliable, convenient to use, and inexpensive."[51]

The Apple II went on sale on June 10, 1977, with a retail price of $1,298.[52] The computer's main internal difference from its predecessor was a completely redesigned TV interface, which held the display in memory. Now not only useful for simple text display, the Apple II included graphics and, eventually, color. During the development of the Apple II, Jobs pressed for a well-designed plastic case and built-in keyboard, with the idea that the machine should be fully packaged and ready to run out of the box.[53] This was almost the case for the Apple I computers, but one still needed to plug various parts together and type in the code to run BASIC. Jobs wanted the Apple II case to be "simple and elegant", and hired an industrial designer named Jerry Manock to produce such a case design.[53] Apple employee #5 Rod Holt developed the switching power supply.[54] While early Apple II models use ordinary cassette tapes as storage devices, they were superseded in 1978 by the introduction of a 5+1⁄4-inch floppy disk drive and interface called the Disk II.[55][56] The Disk II system was designed by Wozniak and released with a retail price of $495.[55]

In 1979, the Apple II was chosen to be the desktop platform for what became the first killer application of the business world: VisiCalc, a spreadsheet.[55] So important that the Apple II became what John Markoff described as a "VisiCalc accessory",[57] the application created a business market for the computer and gave home users an additional reason to buy it: compatibility with the office.[55] Before VisiCalc, Apple had been a distant third place competitor to Commodore and Tandy.[58][59]

The Apple II was one of the three "1977 Trinity" computers generally credited with creating the home computer market (the other two being the Commodore PET and the Tandy Corporation TRS-80).[60] A number of different models of the Apple II were built thereafter, including the Apple IIe and Apple IIGS,[61] which continued in public use for nearly two decades. The Apple II series went on to sell about six million units in total before it was discontinued in 1993.[62][63]

Apple III

[edit]

While the Apple II was already established as a successful business-ready platform because of VisiCalc, Apple management was not content. The Apple III was designed to take on the business environment in an attempt to compete with IBM in the business and corporate computing market.[64] The development of the Apple III started in late 1978 under the guidance of Wendell Sander,[65] and was subsequently developed by a committee headed by Jobs.[66] The Apple III was first announced on May 19, 1980, with a retail price ranging from $4,340 to $7,800, and released in November 1980.[66]

The Apple III was a conservative design for the era, however Jobs wanted the heat generated by the electronics to be dissipated through the chassis of the machine rather than by the more usual cooling fan. The case was not sufficient to cool the components and the Apple III was prone to overheating, causing the integrated circuit chips to disconnect from the motherboard. Customers who contacted Apple customer service were told to raise their computers into the air, and then let go to cause the integrated circuits to fall back into place. Thousands of Apple III computers were recalled. A new model was introduced in 1983 to try to rectify the problems, but the damage was already done.

Apple IPO

[edit]In the July 1980 issue of Kilobaud Microcomputing, publisher Wayne Green stated that "the best consumer ads I've seen have been those by Apple. They are attention-getting, and they must be prompting sale."[67] In August, the Financial Times reported that

Apple Computer, the fast growing Californian manufacturer of small computers for the consumer, business and educational markets, is planning to go public later this year. [It] is the largest private manufacturer in the U.S. of small computers. Founded about five years ago as a small workshop business, it has become the second largest manufacturer of small computers, after the Radio Shack division of the Tandy company.[68]

On December 12, 1980, Apple went public on the NASDAQ stock exchange with the ticker symbol "AAPL", selling 4.6 million shares at $22 per share ($.10 per share when adjusting for stock splits as of November 30, 2020[update]),[69] generating over $100 million, which was more capital than any IPO since Ford Motor Company in 1956.[70] Several venture capitalists cashed out, reaping billions in long-term capital gains. By the end of the day, the stock rose to $29 per share and 300 millionaires were created, including the two Steves.[71][72] Around this time Wozniak offered $10 million of his own stock to early Apple employees, something Jobs refused to do.[71] Apple's market cap was $1.778 billion at the end of its first day of trading.[70][72]

In January 1981, Apple held its first shareholders meeting as a public company in the Flint Center, a large auditorium at nearby De Anza College (which is often used for symphony concerts) to handle the larger numbers of shareholders post-IPO. The business of the meeting had been planned so that the voting could be staged in 15 minutes or less. In most cases, voting proxies are collected by mail and counted days or months before a meeting. In this case, after the IPO, many shares were in new hands.

Jobs started his prepared speech, but after being interrupted by voting several times, he dropped his prepared speech and delivered a long, emotionally charged talk about betrayal, lack of respect, and related topics.[73]

Competition from the IBM PC

[edit]By August 1981 Apple was among the three largest microcomputer companies, perhaps having replaced Radio Shack as the leader;[74] revenue in the first half of the year had already exceeded 1980's $118 million, and InfoWorld reported that lack of production capacity was constraining growth.[75] Because of VisiCalc, businesses purchased 90% of Apple II computers;[76][77] large customers especially preferred Apple.[78]

IBM entered the personal computer market that month with the IBM PC[79][80] in part because it did not want products without IBM logos on customers' desks,[81] but Apple had many advantages. While IBM began with one microcomputer, little available hardware or software, and a couple of hundred dealers, Apple had five times as many dealers in the US and an established international distribution network. The Apple II had an installed base of more than 250,000 customers, and hundreds of independent developers offered software and peripherals; at least ten databases and ten word processors were available, while the PC had no databases and one word processor.[82]

The company's customers gained a reputation for devotion and loyalty. BYTE in 1984 stated that[83]

There are two kinds of people in the world: people who say Apple isn't just a company, it's a cause; and people who say Apple isn't a cause, it's just a company. Both groups are right. Nature has suspended the principle of noncontradiction where Apple is concerned. Apple is more than just a company because its founding has some of the qualities of myth ... Apple is two guys in a garage undertaking the mission of bringing computing power, once reserved for big corporations, to ordinary individuals with ordinary budgets. The company's growth from two guys to a billion-dollar corporation exemplifies the American Dream. Even as a large corporation, Apple plays David to IBM's Goliath, and thus has the sympathetic role in that myth.

The magazine noted that the loyalty was not entirely positive for Apple; customers were willing to overlook real flaws in its products, even while holding the company to a higher standard than for competitors.[83] The Apple III was an example of its autocratic reputation among dealers[78] that one described as "Apple arrogance".[84] After examining a PC and finding it unimpressive, Apple confidently purchased a full-page advertisement in The Wall Street Journal with the headline "Welcome, IBM. Seriously".[85][80] The company prioritized the III for three years, spending what Wozniak estimated as $100 million on marketing and R&D while not improving the Apple II to compete with the PC, as doing so could hurt III sales.[77]

Microsoft head Bill Gates was at Apple headquarters the day of IBM's announcement and later said "They didn't seem to care. It took them a full year to realize what had happened".[80] The PC almost completely ended sales of the III, the company's most comparable product. The II still sold well,[81] with Apple being the leading computer manufacturer in the United States where 7 million units were sold between 1978 and 1982.[86] But by 1983, the PC surpassed the Apple II as the best-selling personal computer.[87] IBM recruited the best Apple dealers while avoiding the discount grey market they disliked.[81] The head of a retail chain said "It appears that IBM had a better understanding of why the Apple II was successful than had Apple".[78] Gene Amdahl predicted that Apple would be another of the many "brash young companies" that IBM had defeated.[88]

By 1984 the press called the two companies archrivals,[89] but IBM had $4 billion in annual PC revenue, more than twice that of Apple and as much as the sales of it and the next three companies combined.[90] A Fortune survey found that 56% of American companies with personal computers used IBM PCs, compared to 16% for Apple.[91] Small businesses, schools, and some homes became the II's primary market.[76]

Xerox PARC and the Lisa

[edit]

Apple Computer's business division was focused on the Apple III, another iteration of the text-based computer. Simultaneously the Lisa group worked on a new machine that would feature a completely different interface and introduce the words mouse, icon, and desktop into the lexicon of the computing public. In return for the right to buy US$1,000,000 of pre-IPO stock, Xerox granted Apple Computer three days access to the PARC facilities. After visiting PARC, they came away with new ideas that would complete the foundation for Apple Computer's first GUI computer, the Apple Lisa.[92][93][94][95] The first iteration of Apple's WIMP interface was a floppy disk where files could be spatially moved around. After months of usability testing, Apple designed the Lisa interface of windows and icons. The Lisa was introduced in 1983 at a cost of US$9,995 (equivalent to $30,600 in 2023). Because of the high price, Lisa failed to penetrate the business market.

Macintosh and the "1984" commercial

[edit]

By 1984 computer dealers saw Apple as the only clear alternative to IBM's influence;[96] some even promoted its products to reduce dependence on the PC.[81] The company announced the Macintosh 128K to the press in October 1983, followed by an 18-page brochure included with magazines in December.[97] Its debut was announced by a single national broadcast of a US$1.5 million television commercial, "1984" (equivalent to $4,400,000 in 2023). Directed by Ridley Scott and aired during the third quarter of Super Bowl XVIII on January 22, 1984,[98] it is considered a "watershed event"[99] and a "masterpiece."[100] The commercial alludes to George Orwell's novel Nineteen Eighty-Four which describes a dystopian future of enforced conformity. In the commercial a heroine represents the coming of the Macintosh to save humanity,[101] and ends with the words: "On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you'll see why 1984 won't be like 1984.”[102]

On January 24, 1984, the Macintosh went on sale with a retail price of $2,495.[103][104] It came bundled with two applications designed to show off its interface: MacWrite and MacPaint. On the same day, an emotional Jobs introduced the computer to a wildly enthusiastic audience at Apple's annual shareholders meeting held in the Flint Auditorium;[105][106] Macintosh engineer Andy Hertzfeld described the scene as "pandemonium".[107] Jobs had directed the development of the Macintosh since 1981, when he took over the project from early Apple employee Jef Raskin, who conceived the computer,[108][109] and Wozniak, who led the initial design and development with Raskin but was on leave during this time due to an airplane crash earlier that year, making it easier for Jobs to take over the program.[110][111] The Macintosh was based on The Lisa (and Xerox PARC's mouse-driven graphical user interface),[112][113] and it was widely acclaimed by the media with strong initial sales supporting it.[114][115] However, the slow processing speed and limited software led to a rapid sales decline in the second half of 1984.[114][115][116]

The Macintosh was too radical for some, who labeled it a mere "toy". Because the machine was entirely designed around the GUI, existing text-mode and command-driven applications had to be redesigned and the programming code rewritten; this was a challenging undertaking that many software developers shied away from, and resulted in an initial lack of software for the new system. In April 1984 Microsoft's Multiplan migrated over from MS-DOS, followed by Microsoft Word in January 1985.[117] In 1985, Lotus Software introduced Lotus Jazz after the success of Lotus 1-2-3 for the IBM PC, although it was largely a flop.[118] Apple introduced Macintosh Office the same year with the lemmings ad, infamous for insulting potential customers. It was not successful.[119]

For a special post-election edition of Newsweek in November 1984, Apple spent more than US$2.5 million to buy all 39 of the advertising pages in the issue.[120] Apple also ran a "Test Drive a Macintosh" promotion, in which potential buyers with a credit card could take home a Macintosh for 24 hours and return it to a dealer afterwards. While 200,000 people participated, dealers disliked the promotion, the supply of computers was insufficient for demand, and many were returned in such a bad shape that they could no longer be sold. This marketing campaign caused CEO John Sculley to raise the price from US$1,995 (equivalent to $5,900 in 2023) to US$2,495 (equivalent to $7,300 in 2023).[119]

Jobs and Wozniak leave Apple

[edit]By early 1985, the Macintosh's failure to defeat the IBM PC[114][115] triggered a power struggle between Jobs and CEO John Sculley, who had been hired two years earlier by Jobs[121][122] using the famous line, "Do you want to sell sugar water for the rest of your life or come with me and change the world?"[123] Sculley and Jobs' visions for the company greatly differed. The former favored open architecture computers like the Apple II, sold to education, small business, and home markets less vulnerable to IBM. Jobs wanted the company to focus on the closed architecture Macintosh as a business alternative to the IBM PC. President and CEO Sculley had little control over chairman of the Board Jobs' Macintosh division; it and the Apple II division operated like separate companies, duplicating services.[124] Although its products provided 85% of Apple's sales in early 1985, the company's January 1985 annual meeting did not mention the Apple II division or employees. This frustrated Wozniak, who left active employment at Apple in the spring of that year to pursue other ventures, stating that the company had "been going in the wrong direction for the last five years" and sold most of his stock.[125][126][127] Despite these grievances, Wozniak left the company amicably and as of January 2018 continues to represent Apple at events or in interviews,[126] receiving a stipend over the years for this role estimated in 2006 to be $120,000 per year.[128] Wozniak also remained an Apple shareholder following his departure.[129]

Wozniak's first venture after leaving Apple was founding CL 9 in 1985 and creating the first programmable universal remote control two years later, called the "CORE", stating that "I never felt like I was turning my back on my own company [Apple]." He told Apple's director of engineering Wayne Rosing about his decision to step away from the company, but not his longtime business partner and friend Steve Jobs. Wozniak guessed that Jobs first heard the news from an article in The Wall Street Journal where he mentioned that he wasn't leaving because he was disgruntled with Apple, but that he was excited to build a new remote control. The article nevertheless included some of Wozniak's criticisms of Apple, and Wozniak later said "it was an accident, but it's been picked up by every book and every bit of history [since]."[128]: 289

In April 1985, Sculley decided to remove Jobs as the general manager of the Macintosh division, and gained unanimous support from the Apple board of directors.[130][121] Rather than submit to Sculley's direction, Jobs attempted to oust him from his leadership role at Apple.[131] Informed by Jean-Louis Gassée, Sculley found out that Jobs had been attempting to organize a coup and called an emergency executive meeting at which Apple's executive staff sided with Sculley and stripped Jobs of all operational duties.[131]

Jobs, while taking the position of Chairman of the firm, had no influence over Apple's direction and resigned in September 1985, taking a number of Apple employees with him to found NeXT Inc.[132] In a show of defiance at being set aside by Apple Computer, Jobs sold all but one of his 6.5 million shares in the company for $70 million. Jobs then acquired the visual effects house, Pixar for $5M (equivalent to $13,900,000 in 2023). NeXT Inc. built computers with futuristic designs and the UNIX-derived NEXTSTEP operating system. NeXTSTEP eventually developed into Mac OS X. While not a commercial success, due in part to its high price, the NeXT computer introduced important concepts to the history of the personal computer, including serving as the initial platform for Tim Berners-Lee as he was developing the World Wide Web.[133]

Sculley reorganized the company, unifying sales and marketing in one division and product operations and development in another.[134][124] Despite initial marketing difficulties, the Macintosh brand was eventually a success for Apple, due to its introduction of desktop publishing (and later computer animation) through Apple's partnership with Adobe Systems, which introduced the laser printer and Adobe PageMaker. The Macintosh became the default platform for many arts industries including cinema, music, advertising, and publishing.

1985–1997: Sculley, Spindler, Amelio

[edit]Corporate performance

[edit]

Under leadership of John Sculley, Apple issued its first corporate stock dividend on May 11, 1987. A month later on June 16, Apple stock split for the first time in a 2:1 split. Between March 1988 and January 1989, Apple undertook five acquisitions, including software companies Network Innovations,[135] Styleware,[136] Nashoba Systems,[137] and Coral Software,[138] as well as satellite communications company Orion Network Systems.[139]

Apple continued to sell both lines of its computers, the Apple II and the Macintosh. A few months after introducing the Mac, Apple released a compact version of the Apple II called the Apple IIc. And in 1986 Apple introduced the Apple IIGS, an Apple II positioned as something of a hybrid product with a mouse-driven, Mac-like operating environment. Even with the release of the first Macintosh, Apple II computers remained the main source of income for Apple for years.[140]

The Mac family

[edit]

At the same time, the Mac was becoming a product family of its own. The original model evolved into the Mac Plus in 1986 and spawned the Mac SE and the Mac II in 1987 and the Mac Classic and Mac LC in 1990. Meanwhile, Apple attempted its first portable Macs: the failed Macintosh Portable in 1989 and then the more popular PowerBook in 1991, a landmark product that established the modern form and ergonomic layout of the laptop. Popular products and increasing revenues made this a good time for Apple. MacAddict magazine has called 1989 to 1991 the "first golden age" of the Macintosh. On February 19, 1987, Apple registered the "Apple.com" domain name, making it one of the first hundred companies to register a .com address on the nascent Internet.[141]

Early-mid-1990s

[edit]

In the late 1980s, Apple's fiercest technological rivals were the Amiga and Atari ST platforms. But computers based on the IBM PC were far more popular than all three, and by the 1990s, they finally had a comparable GUI thanks to Windows 3.0, and were out-competing Apple.

Apple's response to the PC threat was a profusion of new Macintosh lines including Quadra, Centris, and Performa. These new lines were marketed poorly by what was now "arguably one of the worst-managed companies in the industry".[142] There were too many models, differentiated by very minor graduations in technical specifications. The profusion of arbitrary model numbers confused consumers and hurt Apple's reputation for simplicity. Resellers like Sears and CompUSA often failed to sell or even competently display these Macs. Inventory grew as Apple consistently underestimated demand for popular models and overestimated demand for others.[142]

In 1991, Apple partnered with long-time competitor IBM and Motorola to form the AIM alliance, with the ultimate goal to create a revolutionary new computing platform, known as PReP, using IBM and Motorola hardware and Apple software. As the first step, Apple started the Power Macintosh line in 1994, using PowerPC processors from Motorola and IBM. The RISC architecture of these processors differed substantially from the Motorola 680X0 series used by previous Macs. Parts of Apple's operating system were rewritten to allow some older Mac software to run in emulation on the PowerPC series.[citation needed] Apple refused IBM's offer to purchase the company, but later unsuccessfully sought another offer from IBM,[143] and at one point was "hours away" from an acquisition by Sun Microsystems.[142][144] In 1993, Apple released the Newton, a failed early personal digital assistant (PDA).

Need for a new OS

[edit]In 1994 Apple launched eWorld, an online service providing email, news and a bulletin board system to replace AppleLink. It was shut down in 1996.[145] In 1995, to achieve deeper market penetration and extra revenue, Apple officially began licensing the Mac OS and Macintosh ROMs to 3rd party manufacturers. The "Clonintoshes" competed with Apple's own Mac's and reduced Apple's sales.[146] Apple had market share of over 10% until Jobs was re-hired in 1997 as interim CEO to replace Gil Amelio, and found a loophole to terminate the Macintosh OS licensing program. Macintosh's market share fell to around 3%.[147]

During the 90's, "project Pink" had Apple and IBM collaborating to develop a new operating system, named Taligent to replace System 7. Infighting resulted in Apple leaving the project and IBM finishing it. Apple started project Copland, another effort to replace System 7, but it was affected by Feature creep then Development hell due to software planned for Taligent being reworked for Copland. Ultimately Copland was scrapped.[148] With the Copland project in disarray, Apple decided it needed to acquire another company's operating system. Candidates considered were Sun's Solaris and Windows NT. Hancock was in favor of Solaris, while Amelio preferred Windows. Amelio called Bill Gates, and Gates promised Microsoft engineers would port QuickDraw to NT.[149]

Acquisition of NeXT

[edit]In 1996, the struggling NeXT company beat Be Inc.'s BeOS bid to sell its operating system to Apple.[150] On December 20, 1996, Apple announced it would purchase NeXT, and its NeXTstep operating system, for $429 million and 1.5 million shares of Apple stock.[151] This brought Jobs back to Apple's management for the first time since 1985, and NeXT technology became the foundation of the Mac OS X operating system.

1997–2001: Apple's comeback

[edit]Return of Steve Jobs

[edit]On July 9, 1997, Gil Amelio was ousted as CEO of Apple by the board of directors. Fred D. Anderson was the head of the directors in short term and obtained short-term working capital from the banks in July 1997.[152][153] In August 1997, Jobs stepped in as the interim CEO to begin a critical restructuring of the company's product line.[5] He eventually became CEO and served in that position from January 2000 to August 2011.[6] On August 24, 2011, Jobs resigned his position as chief executive officer of Apple before his long battle with pancreatic cancer took his life on October 5, 2011.[154] On November 10, Apple introduced the Apple Store, an online retail store based upon the WebObjects application server the company had acquired in its purchase of NeXT. The new direct sales outlet was tied to a new build-to-order manufacturing strategy.[155][156]

Microsoft deal

[edit]At the 1997 Macworld Expo, Jobs announced that Apple would begin a partnership with Microsoft, with terms including a five-year commitment from Microsoft to release Microsoft Office for Macintosh, and a US$150 million investment in Apple. The long-standing dispute over whether Windows infringed Apple patents was settled,[157] and Internet Explorer would ship as the Macintosh's default browser, with the user able to have a preference. Microsoft chairman Bill Gates appeared on-screen explaining plans for developing Mac software, and expressing excitement to be helping Apple return to success. Jobs addressed the audience:

If we want to move forward and see Apple healthy and prospering again, we have to let go of a few things here. We have to let go of this notion that for Apple to win, Microsoft has to lose. We have to embrace a notion that for Apple to win, Apple has to do a really good job. And if others are going to help us that's great, because we need all the help we can get, and if we screw up and we don't do a good job, it's not somebody else's fault, it's our fault. So I think that is a very important perspective. If we want Microsoft Office on the Mac, we better treat the company that puts it out with a little bit of gratitude; we'd like their software. So, the era of setting this up as a competition between Apple and Microsoft is over as far as I'm concerned. This is about getting Apple healthy, this is about Apple being able to make incredibly great contributions to the industry and to get healthy and prosper again.[158]

The day before the announcement Apple had a market cap of $2.46 billion,[159] and had ended its previous quarter with quarterly revenues of US$1.7 billion and cash reserves of US$1.2 billion,[160] making the US$150 million amount of the investment largely symbolic. Apple CFO Fred Anderson stated that Apple would use the additional funds to invest in its core markets of education and creative content.[157]

iMac, iBook, and Power Mac G4

[edit]

While discontinuing Apple's licensing of its operating system to third-party computer manufacturers, one of Jobs's first moves as new acting CEO was to develop the iMac, which bought Apple time to restructure. The original iMac integrated a CRT display and CPU into a streamlined, translucent plastic body. The line became a sales smash, moving about one million units each year. It helped re-introduce Apple to the media and public and announced the company's new emphasis on the design and aesthetics of its products.

In 1999, Apple introduced the Power Mac G4, which utilized the Motorola-made PowerPC 7400 containing a 128-bit instruction unit known as AltiVec, its flagship processor line. Apple unveiled the iBook that year, its first consumer-oriented laptop, the first Macintosh to support the use of Wireless LAN via the optional AirPort card. Based on the 802.11b standard, it helped popularize Wireless LAN technology to connect computers to networks.

Mac OS X

[edit]

In 2001, Apple introduced Mac OS X, an operating system based on NeXT's NeXTSTEP and incorporating parts of the FreeBSD kernel.[161] Aimed at consumers and professionals alike, Mac OS X married the stability, reliability and security of Unix with the ease of a completely overhauled user interface. To help users transition, the new operating system allowed the use of Mac OS 9 applications through the Classic environment. Apple's Carbon API allowed developers to adapt Mac OS 9 software to use Mac OS X's features.

Retail stores

[edit]In May 2001, after much speculation, Apple announced the opening of a line of Apple retail stores, to be located throughout the major U.S. computer buying markets. The stores were designed for two primary purposes: to stem the tide of Apple's declining share of the computer market and to respond to poor marketing of Apple products at third-party retail outlets.

2001–2007: iPods, iTunes Store, Intel transition

[edit]iPod

[edit]

In October 2001, Apple introduced its first iPod portable digital audio player. Then iPod started as a 5 gigabyte player capable of storing around 1000 songs. It then evolved into an array of products including the Mini (discontinued), the iPod Touch (discontinued), the Shuffle (discontinued), the iPod Classic (discontinued), the Nano (discontinued), the iPhone and the iPad. Since March 2011, the largest storage capacity for an iPod has been 160 gigabytes.[162] Speaking to software developers on June 6, 2005, Jobs said the company's share of the entire portable music device market stood at 76%.[163]

The iPod gave an enormous lift to Apple's financial results.[164] In the quarter ending March 26, 2005, Apple earned US$290 million, or 34¢ a share, on sales of US$3.24 billion. The year before in the same quarter, Apple earned just US$46 million, or 6¢ a share, on revenue of US$1.91 billion.

Moving on from colored plastics and the PowerPC G3

[edit]

In early 2002, Apple unveiled a completely redesigned iMac, using the G4 processor and LCD display. The new iMac G4 design had a white hemispherical base and a flat panel all-digital display supported by a swiveling chrome neck. After several iterations increasing the processing speed and screen sizes from 15" to 17" to 20" the iMac G4 was discontinued and replaced by the iMac G5 in the summer of 2004.

Later in 2002, Apple released the Xserve 1U rack mounted server. Originally featuring two G4 chips, the Xserve was unusual for Apple in two ways. It represented an earnest effort to enter the enterprise computer market, and it was cheaper than competitors' similar machines. This was largely due to Fast ATA drives as opposed to the SCSI hard drives used in traditional rack-mounted servers. Apple later released the Xserve RAID, a 14 drive RAID that was again cheaper than competing systems.

In mid-2003, Jobs launched the Power Mac G5, based on IBM's G5 processor. Its all-metal anodized aluminum chassis finished Apple's transition away from colored plastics in their computers. Apple claims this was the first 64-bit computer sold to the general public. The Power Mac G5 was used by Virginia Tech to build its prototype System X supercomputing cluster, which at the time was considered the third-fastest supercomputer in the world. It cost only US$5.2 million to build, far less than the previous No. 3 and other ranking supercomputers. Apple's Xserves were updated to use the G5 as well. They replaced the Power Mac G5 machines as the main building block of Virginia Tech's System X, which was ranked in November 2004 as the world's seventh-fastest supercomputer.[165]

A new iMac based on the G5 processor was unveiled August 31, 2004, and was made available in mid-September. This model dispensed with the base altogether, placing the CPU and the rest of the computing hardware behind the flat-panel screen, which is suspended from a streamlined aluminum foot. This new iMac, dubbed the iMac G5, was the "world's thinnest desktop computer",[166] measuring in at around two inches (around 5 centimeters).[167]

In 2004, after creating a sizable financial base to work with, the company began experimenting with new parts from new suppliers. Apple could produce new designs quickly, and released the iPod Video, then the iPod Classic, and eventually the iPod touch and iPhone. On April 29, 2005, Apple released Mac OS X v10.4 "Tiger".

Apple's successful PowerBook and iBook relied on previous generation G4 architecture produced by Freescale Semiconductor, a spin-off from Motorola. IBM engineers had some success in making their PowerPC G5 processor consume less power and run cooler, but not enough to run in iBook or PowerBook formats. In October 2005, Apple released the Power Mac G5 Dual featuring a Dual-Core processor – two cores in one rather than two separate processors. The Power Mac G5 Quad uses two Dual-Core processors. The Power Mac G5 Dual cores run individually at 2.0 GHz or 2.3 GHz. The Power Mac G5 Quad cores run individually at 2.5 GHz, and all variations have a graphics processor with 256-bit memory bandwidth.[168]

Retail store expansion

[edit]

Initially, Apple Stores were only in the United States, but in late 2003, Apple opened its first Apple Store abroad, in Tokyo's Ginza district. It was followed by a store in Osaka, Japan in August 2004. In 2005, Apple opened stores in Nagoya, the Shibuya district of Tokyo, Fukuoka, and Sendai. A store opened in Sapporo in 2006. Apple's first European store opened in London, on Regent Street, in November 2004. A store in the Bullring shopping centre in Birmingham opened in April 2005, and the Bluewater shopping centre in Dartford, Kent opened in July 2005. Apple opened its first store in Canada in the middle of 2005 at the Yorkdale Shopping Centre in North York, Toronto. Later in 2005 Apple opened the Meadowhall Store in Sheffield and the Trafford Centre Store in Manchester, UK. Later additions in the London area include Brent Cross (January 2006), Westfield in Shepherd's Bush (September 2008), and Covent Garden (August 2010), which at 40,000 square feet (3,700 m2) was, as of 2015, the largest Apple Store in the world.[169]

Apple opened several "mini" stores in October 2004 to capture markets where demand does not necessarily dictate a full-scale store. The first of these stores was opened at Stanford Shopping Center in Palo Alto, California. These stores are only one half the square footage of the smallest normal store.

Apple and "i" Web services

[edit]In 2000, Apple introduced iTools, a set of free web-based tools that included an email account, internet greeting cards called iCards, a Web site review service called iReview, and "KidSafe", to prevent children browsing inappropriate websites. The latter two services were canceled because of lack of success. iCards and email were integrated into Apple's .Mac subscription-based service introduced in 2002 and discontinued in mid-2008 to make way for MobileMe, coinciding with the iPhone 3G release. MobileMe, at the same US$99.00 annual subscription as its dotMac predecessor, featured "push" services to instantly and automatically send emails, contacts and calendar updates directly to users' iPhones. Controversy around the release of MobileMe resulted in downtime and a significantly longer release window. Apple extended existing MobileMe subscriptions by 30 days free-of-charge.[170] At the WWDC event in June 2011, Apple announced iCloud, keeping most MobileMe services but dropping iDisk, Gallery, and iWeb. It added Find my Mac, iTunes Match, Photo Stream, Documents & Data Backup, and iCloud backup for iOS devices. The service requires iOS 5 and OS X 10.7 Lion.

iTunes Store

[edit]The iTunes Music Store was launched in April 2003, with 2 million downloads in the first 16 days. Music was purchased through the iTunes application, which was initially Macintosh-only; in October 2003, support for Windows was added. Initially, the music store was only available in the United States due to licensing restrictions.

In June 2004 Apple opened its iTunes Music Store in the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. A version for the European Union version opened October 2004, but it was not initially available in the Republic of Ireland due to the intransigence of the Irish Recorded Music Association (IRMA) but was opened there a few months later on Thursday, January 6, 2005. A version for Canada opened in December 2004. On May 10, 2005, the iTunes Music Store was expanded to Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland.

On December 16, 2004, Apple sold its 200 millionth song on the iTunes Music Store to Ryan Alekman from Belchertown, Massachusetts. The download was The Complete U2, by U2.[171] Just under three months later Apple sold its 300 millionth song on March 2, 2005.[172] On July 17, 2005, the iTunes Music Store sold its 500 millionth song.[173] At that point, songs were selling at an accelerating annualized rate of more than 500 million.

On October 25, 2005, the iTunes Store went live in Australia, with songs selling for A$1.69 each, albums at (generally) A$16.99 and music videos and Pixar short films at A$3.39. Before the loophole was closed, people in New Zealand were briefly able to buy music from the Australian store On February 23, 2006, the iTunes Music Store sold its 1 billionth song.[174]

The iTunes Music Store changed its name to iTunes Store on September 12, 2006, when it began offering video content (TV shows and movies) for sale. Since iTunes' inception, it has sold over 2 billion songs, 1.2 billion of which were sold in 2006. Since downloadable TV and movie content was added 50 million TV episodes and 1.3 million movies have been downloaded. In early 2010, Apple celebrated the 10 billionth song downloaded from the iTunes Music Store.[175]

Intel transition

[edit]

In a keynote address on June 6, 2005, Jobs announced that Apple would produce Intel-based Macintosh computers beginning in 2006.[176] Jobs confirmed rumors that the company had been secretly producing versions of Mac OS X for both PowerPC and Intel processors over the past 5 years, and that the transition to Intel processor systems would last until the end of 2007. Rumors of cross-platform compatibility had been spurred by the fact that Mac OS X is based on OPENSTEP, an operating system that was available for many platforms. Apple's own Darwin, the open source underpinnings of Mac OS X, was also available for Intel's x86 architecture.[177][178][179]

On January 10, 2006, the Intel-based iMac and MacBook Pro were introduced,[180][181] based on the Intel Core Duo platform. They came alongside news that Apple would complete the transition to Intel processors on all hardware by the end of 2006, a year ahead of the originally quoted schedule.

2007–2011: Apple Inc., iPhone, iOS, iPad

[edit]On January 9, 2007, Apple Computer, Inc. shortened its name to simply Apple Inc. In his Macworld Expo keynote address, Jobs explained that with their current product mix consisting of the iPod and Apple TV as well as their Macintosh brand, Apple really wasn't just a computer company anymore. At the same address, Jobs revealed a product that would revolutionize an industry in which Apple had never previously competed: the Apple iPhone. The iPhone combined Apple's first widescreen iPod with the world's first mobile device boasting visual voicemail, and an internet communicator able to run a fully-functional version of Apple's web browser, Safari, on the then-named iPhone OS (later renamed iOS).

iOS evolution: iPhone and iPad

[edit]

The first version of the iPhone became publicly available on June 29, 2007, in selected countries/markets. It was another 12 months before the iPhone 3G became available on July 11, 2008. Apple announced the iPhone 3GS on June 8, 2009, along with plans to release it later in June, July, and August, starting with the U.S., Canada, and major European countries on June 19. This 12-month iteration cycle has continued with the iPhone 4 model arriving in similar fashion in 2010, a Verizon model was released in February 2011, and a Sprint model in October 2011, shortly after Jobs' death.

On February 10, 2011, the iPhone 4 was made available on both Verizon Wireless and AT&T. Now two iPod types are multi-touch: the iPod nano and the iPod touch, a big advance in technology. Apple TV currently has a 2nd-generation model, which is 4 times smaller than the original Apple TV. Apple has also gone wireless, selling a wireless trackpad, keyboard, mouse, and external hard drive. Wired accessories are still available.

The Apple iPad was announced on January 27, 2010, with retail availability commencing in April and systematically growing in markets throughout 2010. The iPad fits into Apple's iOS product line, being twice the screen size of an iPhone without the phone abilities. While there were initial fears of product cannibalization the FY2010 financial results released in Jan 2011 included commentary of a reverse 'halo' effect, where iPad sales were leading to increased sales of iMacs and MacBooks.[182]

Resurgence compared to Microsoft

[edit]Since 2005, Apple's revenues, profits, and stock price have grown significantly. On May 26, 2010, Apple's stock market value overtook Microsoft's,[183][184][185] and Apple's revenues surpassed those of Microsoft in the third quarter of 2010.[186][187] After giving their results for the first quarter of 2011, Microsoft's net profits of $5.2 billion were lower for the quarter than those of Apple, which earned $6 billion in net profit for the quarter.[188][189] The late April announcement of profits by the companies marked the first time in 20 years that Microsoft's profits had been lower than Apple's,[190] a situation described by Ars Technica as "unimaginable a decade ago".[188]

The Guardian reported that one of the reasons for the change was because PC software, where Microsoft dominates, has become less important compared to the tablet and smartphone markets, where Apple has a strong presence.[190] One reason for this was a surprise drop in PC sales in the quarter.[190] Another issue for Microsoft was that its online search business had lost a lot of money, with a loss of $700 million in the first quarter of 2010.[190]

2011–2020: Restructuring and Apple Watch

[edit]On March 2, 2011, Apple unveiled the iPad's second-generation model, the iPad 2. Like the 4th-generation iPod Touch and iPhone, the iPad 2 comes with a front-facing camera as well as a rear-facing camera, along with three new apps that utilize these new features: Camera, FaceTime, and Photo Booth. On August 24, Jobs resigned from his position as CEO,[191] with Tim Cook taking his place.

On October 29, 2012, Apple announced structural changes to increase collaboration between hardware, software, and services.[192] This involved the departure of Scott Forstall, responsible for the launch of iOS (iPhone OS at the time of launch), who was replaced with Craig Federighi as head of iOS and OS X teams. Jony Ive became head of HI (Human Interface), whilst Eddy Cue was announced as head of online services including Siri and Maps. The most notable short term difference of this restructuring was the launch of iOS 7, the first version of the operating system to use a drastically different design to its predecessors, headed by Jony Ive,[193] followed by OS X Yosemite a year later with a similar design.

During this time, Apple released the iPhone 5, the first iPhone to have a screen larger than 3.5",[194] the iPod Touch 5 with a 4" screen, the iPhone 5S with fingerprint scanning technology in the form of Touch ID, and iPhone 6 and iPhone 6 Plus, with screens at 4.7" and 5.5". They released the 3rd-generation iPad with Retina Display, followed by the 4th-generation iPad just half a year later. The iPad Mini was announced alongside the iPad 4th gen, and was the first to feature a smaller screen than 9.7". This was followed by the iPad Mini 2 with Retina Display in 2013, alongside the iPad Air, a continuation of the original 9.7" range of iPads, which was subsequently followed by the iPad Air 2 with Touch ID in 2014. Apple released various major Mac updates, including the MacBook Pro with Retina Display,[195] whilst discontinuing the original MacBook range for a short period, before reintroducing it in 2015 with various new features, a Retina Display and a new design that implemented USB-C, while removing all other ports.[196] The Mac Pro and iMac were updated with more power and a drastically smaller and thinner profile. On November 25, 2013, Apple acquired a company called PrimeSense.[197]

On May 28, 2014, Apple acquired Beats Electronics, producers of the popular Beats by Dre headphone and speaker range, as well as streaming service Beats Music. On September 9, 2014, Apple announced the Apple Watch, the first new product range since the departure of Jobs.[198] The product cannot function beyond basic features without being within Bluetooth or WiFi range to an iPhone and contains basic applications (many acting as a remote for other devices, such as a music remote, or a control for an Apple TV) and fitness tracking. The Apple Watch received mixed reviews, with critics suggesting that whilst the device showed promise, it lacked a clear purpose, similar to many of the devices already on the market.[199] The Apple Watch was released on April 24, 2015.[200]

On September 9, 2015, Apple announced the iPhone 6S and iPhone 6S Plus with 3D Touch, the iPad Pro, and the fourth-generation Apple TV, along with the fourth-generation iPad Mini. On March 21, 2016, Apple announced the first-generation iPhone SE and the smaller iPad Pro.

On September 7, 2016, Apple announced the iPhone 7 and iPhone 7 Plus with an improved camera and a faster processor than the previous generation. The iPhone 7 and iPhone 7 Plus have high storage options. On October 27, 2016, Apple announced the new 13 and 15 inch MacBook Pro with a retina Touch Bar. On March 21, 2017, Apple announced the iPad (2017). This is the iPad Air 2 successor, equipped with a faster processor, and starts at $329. Apple also announced the (Product)RED iPhone 7 and iPhone 7 Plus.

On June 5, 2017, Apple announced iOS 11 as well as new versions of macOS, watchOS, and tvOS. Updated versions of the iMac, MacBook Pro, and MacBook were released, along with the 10.5 and 12.9 inch iPad Pro, and "HomePod", a Siri speaker similar to the Amazon Echo. On September 12, at the Steve Jobs Theater, Apple introduced the iPhone 8 and iPhone 8 Plus with better camera features, more improvements in product design, user experience, performance and more, and announced the iPhone X with facial recognition technology and wireless charging. Apple announced the 4K Apple TV with 4K, HDR and Dolby Vision experience, and the Apple Watch Series 3, supporting a cellular connection, running watchOS 4.

In March 2018, Bloomberg reported that Apple was developing MicroLED screens for the iPhone, iPad, Mac, watch, AR glasses, and electric car.[201][202][203] It was linked to a Research and Development facility in Santa Clara, California code named Aria[204] by the Bay Area News Group.[205] On September 12, at the Steve Jobs Theater, Apple introduced the iPhone XS, iPhone XS Max, and iPhone XR, running iOS 12, with improved facial recognition and HDR in the display as well as better cameras for all 3 phones. They also announced the Apple Watch Series 4, running watchOS 5, with an all-new design and larger display as well as many more health-related features.

In October 2018, Bloomberg reported that, as early as 2015, a specialized unit of China's People's Liberation Army began inserting chips into Supermicro servers that allowed for backdoor access to them.[206] Approximately 30 companies reportedly had their servers compromised via the chips, including Apple Inc.[206] On September 20, 2019, the iPhone 11, iPhone 11 Pro, and iPhone 11 Pro Max were introduced. The iPhone 11 Pro was the first iPhone to feature three cameras.

2020–present: 5G and Apple silicon

[edit]

In 2020, Apple was fined £21 million euros, claiming they intentionally slowed down older models of iPhones to encourage people to buy newer models. The company somewhat admitted to this practice in 2017, saying the phones were slowed to respond to the decay of iPhones' lithium-ion batteries, which made it harder for the batteries to reach the phones' expected power demands.[207] The COVID-19 pandemic heavily effected China, hurting Apple financially, because they invested into China enough to become increasingly dependent on the country.[208] Chinese factories closed and demand for Apple products went down.[209] However, they recovered and eventually reached a $2 trillion USD market cap later that year.[210] The iPhone 12, 12 Pro, and 12 Pro Max were introduced, being the first iPhones to support 5G connectivity.[211] The company also started using its own Apple silicon processors in Macs, instead of chips made by Intel.[212][213]

In April 2021, the M1-powered iPad was launched, along with a new M1-powered iMac offered in 7 colors, recalling the iMacs offered in 5 colors announced in 1999. Apple launched a GPS tracking device called AirTag that uses the Apple's Find My device network. In 2021 and 2022, Apple repeated its pattern of introducing four new iPhones in September, with 2021's iPhone 13 and iPhone 13 Pro lines and 2022's iPhone 14 and iPhone 14 Pro lines. The iPhone 14 Pro ditched the notch containing the sensors for a "dynamic island", which allows for space between the top edge of the screen and the sensors for Face ID. 2022 saw Apple announce the first Macs with Apple's M2 chip and a new sub-series of Apple Watch with increased performance for outdoor activities named Apple Watch Ultra.

Apple experienced a period of unprecedented employee unrest in 2021 and 2022, resulting in outspoken employees organizing over labor issues and the company's treatment of women at the company in its corporate offices and retail stores.[214][215] Employees engaged in hashtag activism on social media inspired by the #MeToo movement called #AppleToo[216] and two American stores unionized for the first time.[217]

In 2022, Apple paused all product sales in Russia in response to the country's invasion of Ukraine.[218] Tim Cook began focusing on privacy features, which lowered App Store developers' revenue. They also developed App Tracking Transparency, a set of privacy features which cost Facebook $12 billion USD.[208] The company also announced they would start including ads in the Books, Maps, and TV iOS apps,[219] and that it would eventually move production out of China.[220]

Apple launched a buy now, pay later service called 'Apple Pay Later' for its Apple Wallet users in 2023. The program allows its users to apply for loans between $50 and $1,000 to make online or in-app purchases, and then repaying them through four installments spread over six weeks without any interest or fees.[221][222] In June, Apple released the Apple Vision Pro, a computer in the form of an augmented reality headset which runs the VisionOS operating system. Wearers of the headset use hand gestures to navigate the user interface.[223] It initially released at $3,500 in the United States, and while sales figures have not been released as of June 2024, it is considered to be a financial failure in its initial stages.[224] The company then reached a $25 million settlement in a U.S. Department of Justice case that alleged they were discriminating against U.S. citizens in hiring; they created jobs that were not listed online and required paper submission to apply for, while advertising these jobs to foreign workers as part of recruitment for PERM.[225]

In April 2024, Apple laid off more than 600 employees working in facilities linked to the electric car project and microLED development.[226] The projects had been reported to have been shut down in the preceding two months.[227][228]

In June 2024, Apple announced iOS18 and macOS Sequoia.[229][230] After the development of powerful AI software like OpenAI's ChatGPT in the early 2020s, Apple was accused of being behind their competitors in innovating using AI;[231] alongside the new operating systems, the company announced they would introduce AI features into their products, such as using ChatGPT to improve Siri. The first product to feature these improvements, named Apple Intelligence, is planned to be the iPhone 15 Pro running iOS 18.[232] Criticism was leveled towards the plan to incorporate recorded user inputs into ChatGPT's data set.[233] Apple did not pay OpenAI for these features, believing that exposure to OpenAI products will already financially benefit them.[234] The announcement improved Apple's stock, temporarily making them the world's most valuable company instead of Microsoft.[235] Meanwhile, Apple was sued by two female employees seeking class action who claimed that the company's hiring and performance-review practices are biased against women.[236]

The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) charged Apple with violations of the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 in spring and fall of 2024. The NLRB accused Apple of maintaining unlawful employee contracts, rules around social media and Slack usage, for interrogating unionizing employees, and for illegally firing Janneke Parrish, a labor activist who had co-lead the #AppleToo movement.[237][238][239]

Financial history

[edit]As cash reserves increased significantly in 2006, Apple created Braeburn Capital on April 6, 2006, to manage its assets.[240]

| Financial period | Net sales (million USD) | Net profits (million USD) | Revenue growth | Return on net sales |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FY 1977[241] | 0.773 | n/a | --- | --- |

| FY 1978 | 7.856 | 0.793 | 920% | 10% |

| FY 1979 | 47.867 | 5.073 | 508% | 11% |

| FY 1980 | 117.126 | 11.698 | 146% | 10% |

| FY 1981[242] | 335 | 39.420 | 184% | 12% |

| FY 1982 | 583 | 61 | 74% | 10% |

| FY 1983 | 983 | 77 | 69% | 8% |

| FY 1984 | 1,516 | 64 | 54% | 4% |

| FY 1985 | 1,918 | 61 | 27% | 3% |

| FY 1986 | 1,902 | 154 | -1% | 8% |

| FY 1987 | 2,661 | 218 | 40% | 8% |

| FY 1988 | 4,071 | 400 | 53% | 10% |

| FY 1989 | 5,284 | 454 | 30% | 9% |

| FY 1990 | 5,558 | 475 | 5% | 9% |

| FY 1991 | 6,309 | 310 | 12% | 5% |

| FY 1992 | 7,087 | 530 | 12% | 7% |

| FY 1993 | 7,977 | 87 | 13% | 1% |

| FY 1994 | 9,189 | 310 | 15% | 3% |

| FY 1995 | 11,062 | 424 | 20% | 4% |

| FY 1996 | 9,833 | −816 | −11% | −8% |

| FY 1997 | 7,081 | −1,045 | −28% | −15% |

| FY 1998 | 5,941 | 309 | −16% | 5% |

| FY 1999 | 6,134 | 601 | 3% | 10% |

| FY 2000 | 7,983 | 786 | 30% | 10% |

| FY 2001 | 5,363 | −37 | −33% | −1% |

| FY 2002 | 5,724 | 65 | 7% | 1% |

| FY 2003 | 6,207 | 57 | 8% | 1% |

| FY 2004 | 8,279 | 266 | 33% | 3% |

| FY 2005 | 13,931 | 1,328 | 68% | 10% |

| FY 2006 | 19,315 | 1,989 | 39% | 10% |

| FY 2007 | 24,006 | 3,496 | 24% | 15% |

| FY 2008 | 32,479 | 4,834 | 35% | 15% |

| FY 2009[243] | 42,905 | 8,235 | 32% | 19% |

| FY 2010 | 65,225 | 14,013 | 52% | 21% |

| FY 2011 | 108,249 | 25,922 | 66% | 24% |

| FY 2012 | 156,508 | 41,733 | 45% | 27% |

| FY 2013 | 170,910 | 37,037 | 9% | 22% |

| FY 2014 | 182,795 | 39,510 | 7% | 22% |

| FY 2015 | 233,715 | 53,394 | 28% | 23% |

| FY 2016 | 215,639 | 45,687 | −8% | 21% |

| FY 2017 | 229,234 | |||

| FY 2018 | 265,595 | 59,531 | 15% | _ |

Stock

[edit]'AAPL' is the stock symbol under which Apple Inc. trades on the NASDAQ stock market. Apple originally went public on December 12, 1980, with an initial public offering at US$22.00[244] per share. The stock has split 2 for 1 three times on June 15, 1987, June 21, 2000, and February 28, 2005. Apple initially paid dividends from June 15, 1987, to December 15, 1995. On March 19, 2012, Apple announced that it would again start paying a dividend of $2.65 per quarter (beginning in the quarter that starts in July 2012) along a $10 billion share buyback that would commence September 30, 2012, the start of its fiscal 2013 year. Gene Munster and Michael Olson of Piper Jaffray are the main analysts who track Apple stock. Piper Jaffray estimates future stock and revenue of Apple annually, and have been doing so for several years.[245]

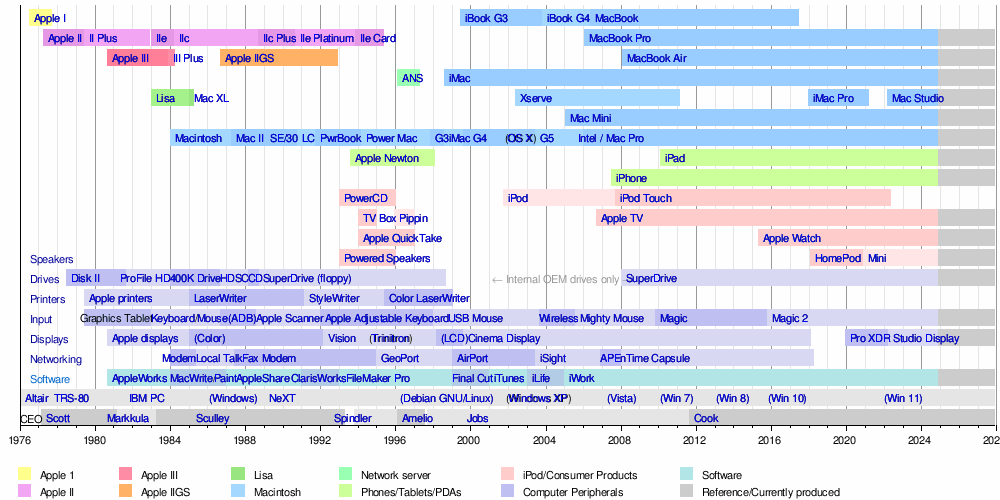

Timeline of Apple Inc. products

[edit]| Timeline of Apple Inc. products |

|---|

|

References

[edit]- ^ Anisimova, Milena (March 8, 2022). "Apple Logo History: All About Apple Logo Evolution". The Designest. Archived from the original on June 24, 2024. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ a b "Apple Computer Company Partnership Agreement" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 28, 2019.

- ^ "FAQ". Apple Investor Relations. Apple Inc. Apple Corporate Info. Archived from the original on March 12, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2023.

- ^ "Apple Computer, Inc. Finalizes Acquisition of NeXT Software Inc". Apple Inc. February 7, 1997. Archived from the original on July 24, 2001. Retrieved June 25, 2006.

- ^ a b "Apple Formally Names Jobs as Interim Chief". The New York Times. September 17, 1997. Archived from the original on November 17, 2017. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ a b Norr, Henry (January 6, 2000). "MacWorld Expo/Permanent Jobs/Apple CEO finally drops 'interim' from title". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "Financial Times". Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ "Apple is first public company worth $1 trillion". BBC News. August 2, 2018. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ Goldman, David (February 29, 2012). "At $500 billion, Apple is worth more than Poland – Feb. 29, 2012". Money.cnn.com. Archived from the original on March 25, 2021. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ "2012 Apple Form 10-K". October 31, 2012. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- ^ a b Linzmayer 2004, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b O'Grady 2009, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Isaacson, Walter (2014). The Innovators. Simon and Schuster. p. 346. ISBN 978-1-4767-0869-0.

- ^ Isaacson 2015, p. 30.

- ^ a b Linzmayer, Owen W. (2004). Apple Confidential 2.0: The Definitive History of the World's Most Colorful Company. No Starch Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 9781593270100.

- ^ a b Linzmayer 2004, p. 5.

- ^ O'Grady, Jason D. (2009). Apple Inc. ABC-CLIO. p. 3. ISBN 9780313362446.

- ^ a b Isaacson 2015, p. 62.

- ^ "Apple co-founder offered first computer design to HP 5 times". AppleInsider. December 7, 2010. Archived from the original on June 18, 2013. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- ^ a b c Linzmayer 2004, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Schlender, Brent; Tetzeli, Rick (2016). Becoming Steve Jobs: The Evolution of a Reckless Upstart into a Visionary Leader. Crown Business; Reprint edition. pp. 37–39. ISBN 9780385347426.

- ^ Wozniak, Steve; Smith, Gina (2007). iWoz: Computer Geek to Cult Icon. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 173. ISBN 9780393066869.

- ^ Linzmayer 2004, p. 8.

- ^ Janoff, Rob (March 22, 2018). "The Apple Logo Story". Archived from the original on June 24, 2024. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

- ^ Williams, Rhiannon (April 1, 2015). "Apple celebrates 39th year on April 1". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- ^ Schlender 2016, p. 39.

- ^ a b c Swaine 2014, pp. 336–338.

- ^ Isaacson 2015, pp. 65–66.

- ^ a b c Linzmayer 2004, pp. 6–8.

- ^ Isaacson, Walter (2015). Steve Jobs. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781501127625. p. 63

- ^ Schlender 2016, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Isaacson 2015, p. 66.

- ^ Young, Jeffrey; William L. Simon (2005). iCon Steve Jobs: The Greatest Second Act in the History of Business. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-471-72083-6.

- ^ Linzmayer 2004, p. 7.

- ^ Wozniak, Steve; Smith, Gina (2007). iWoz: The Autobiography of the Man Who Started the Computer Revolution. Headline Publishing. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-7553-1408-9.

- ^ Williams, Gregg; Moore, Rob (December 1984). "The Apple Story / Part 1: Early History". BYTE (interview). pp. A67. Retrieved October 23, 2013.

- ^ a b Isaacson 2015, pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Linzmayer 2004, pp. 8–10.

- ^ a b Blazeski, Goran (November 25, 2017). "Apple-1, Steve Wozniak's hand-built creation, was Apple's first official product, priced at $666.66". The Vintage News. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- ^ Young, Jeffrey; William L. Simon (2005). iCon Steve Jobs: The Greatest Second Act in the History of Business. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-471-72083-6.

- ^ "Building the digital age". BBC News. November 15, 2007. Archived from the original on October 3, 2019. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- ^ Linzmayer 2004, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Isaacson 2015, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Linzmayer 2004, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d Schlender 2016, pp. 45–47.

- ^ a b Isaacson 2015, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Linzmayer 2004, p. 11.

- ^ Schlender 2016, pp. 48–50.

- ^ Linzmayer 2004, p. 21.

- ^ Swaine, Michael (2014). Fire in the Valley: The Birth and Death of the Personal Computer. Pragmatic Bookshelf. ISBN 9781680503524. p. 344–346

- ^ Wozniak, Steve (May 1977). "System Description / The Apple-II". BYTE. pp. 34–43. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- ^ "June 10, 1977 – Apple II Released Today". This Day in History. Mountain View, CA: Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on June 24, 2024. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- ^ a b Isaacson 2015, pp. 71–74.

- ^ Wozniak, Steve. "woz.org: Comment From e-mail: Why didn't the early Apple II's use Fans?". woz.org. Archived from the original on December 26, 2015. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Linzmayer 2004, pp. 13–15.

- ^ Weyhrich, Steven (April 21, 2002). "Apple II History Chapter 4". Archived from the original on June 24, 2024. Retrieved January 23, 2023.

- ^ Markoff, John (July 5, 1982). "Radio Shack: set apart from the rest of the field". InfoWorld. p. 36. Archived from the original on June 24, 2024. Retrieved February 10, 2015.

- ^ Bagnall, Brian (2005). On the Edge: The Spectacular Rise and Fall of Commodore. Variant Press. pp. 109–112. ISBN 978-0-9738649-0-8.

- ^ "Personal Computer Market Share: 1975–2004". Archived from the original on June 6, 2012. The figures show Mac higher, but that is not a single model.

- ^ Chandler, Alfred Dupont; Hikino, Takashi; Nordenflycht, Andrew Von (June 30, 2009). Inventing the Electronic Century: The Epic Story of the Consumer Electronics and Computer Industries, with a new preface. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674029392. Archived from the original on June 24, 2024. Retrieved February 2, 2023 – via Google Books.

- ^ Linzmayer 2004, pp. 17–20.

- ^ Isaacson 2015, p. 84–85.

- ^ Schlender 2016, pp. 65–66.

- ^ O'Grady 2009, p. 6.

- ^ Linzmayer 2004, pp. 81–82.

- ^ a b Linzmayer 2004, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Green, Wayne (July 1980). "Publisher's Remarks". Kilobaud. p. 6. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- ^ Financial Times, Paul Betts: Apple Computer plans to go public August 29, 1980, pg. 16

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". Apple Inc. Archived from the original on March 12, 2020. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ^ a b Deffree, Suzanne (December 12, 2018). "Apple IPO makes instant millionaires, December 12, 1980". Archived from the original on June 24, 2024. Retrieved January 23, 2023.

- ^ a b Martin, Emmie (April 21, 2017). "Why Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak doesn't trust money". CNBC. Archived from the original on August 7, 2019. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ a b Dilger, Daniel Eran (December 12, 2013). "Apple, Inc. stock IPO created 300 millionaires 33 years ago today". AppleInsider. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ "Apple, Rising". The Pop History Dig.

- ^ Hogan, Thom (August 31, 1981). "From Zero to a Billion in Five Years". InfoWorld. pp. 6–7. Archived from the original on June 24, 2024. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ Hogan, Thom (September 14, 1981). "State of Microcomputing / Some Horses Running Neck and Neck". pp. 10–12. Archived from the original on June 24, 2024. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- ^ a b Mace, Scott (April 9, 1984). "Apple IIe Sales Surge as IIc is Readied". InfoWorld. pp. 54–55. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b Williams, Gregg; Moore, Rob (January 1985). "The Apple Story / Part 2: More History and the Apple III". BYTE (interview). p. 166. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ a b c McMullen, Barbara E.; John F. (February 21, 1984). "Apple Charts The Course For IBM". PC Magazine. p. 122. Archived from the original on June 24, 2024. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ^ Pollack, Andrew (August 13, 1981). "Big I.B.M.'s Little Computer". The New York Times. p. D1. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 21, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c Isaacson, Walter (2013). Steve Jobs. Simon and Schuster. p. 135. ISBN 978-1451648546. Archived from the original on June 24, 2024. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Pollack, Andrew (March 27, 1983). "Big I.B.M. Has Done It Again". The New York Times. p. Section 3, Page 1. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 21, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ^ Rosen Research (November 30, 1981). "From the Rosen Electronics Letter / IBM's impact on microcomputer manufacturers". InfoWorld. pp. 86–87. Archived from the original on March 10, 2023. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- ^ a b Lemmons, Phil (December 1984). "Apple and Its Personal Computers". BYTE. p. A4.

- ^ Dvorak, John C. (November 28, 1983). "Inside Track". InfoWorld. p. 188. Archived from the original on March 9, 2023. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Welcome, IBM. Seriously". InfoWorld. October 5, 1981. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 24, 2024. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ "Table 2: United States (1978–1982)". Computers and People. 33–36. Berkeley Enterprises: 19. 1984. Archived from the original on June 24, 2024. Retrieved November 26, 2021.

Apple (all models) 7,000,000

- ^ Sanger, David E. (August 5, 1985). "Philip Estridge Dies in Jet Crash; Guided IBM Personal Computer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 5, 2010. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ^ Greenwald, John (July 11, 1983). "The Colossus That Works". TIME. Archived from the original on May 14, 2008. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ Bulman, Philip (November 5, 1984). "Big time: IBM skillfully revives lackluster sales of PCjr". Fort Lauderdale News. p. 47. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- ^ Libes, Sol (September 1985). "The Top Ten". BYTE. p. 418. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- ^ Kennedy, Don (April 16, 1985). "PCs Rated Number One". PC Magazine. p. 42. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ^ "Did Steve Jobs steal everything from Xerox PARC?". March 22, 2010.

- ^ "Apple Lore: The creation of the Macintosh". Archived from the original on March 23, 2010.

- ^ "The Xerox PARC Visit". web.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on September 24, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2017.

- ^ "How Xerox Forfeited the PC War". Archived from the original on July 23, 2008.

- ^ Sanger, David E. (November 19, 1984). "I.B.M. Entry Unchallenged at Show". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 24, 2024. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- ^ "Apple Macintosh 18 Page Brochure". DigiBarn Computer Museum. Archived from the original on April 28, 2006. Retrieved April 24, 2006.