Equine intelligence

This article may be a rough translation from French. It may have been generated, in whole or in part, by a computer or by a translator without dual proficiency. (December 2024) |

Equine intelligence, long described in myths and anecdotes, has been the subject of scientific study since the early 20th century. The worldwide fascination for clever horses, such as Clever Hans, gave rise to a long-running controversy over the cognitive abilities of this species. The discovery of the Clever Hans effect, followed by the development of ethological studies, has progressively revealed a high level of social intelligence, evident in horse's behavior. The scientific discipline that studies equine cognition, at the crossroads of ethology and animal psychology, is cognitive ethology.

Although the existence of consciousness among horses is yet to be proven, their remarkable memory has been recognized for centuries. Thanks to their wild herd lifestyle, horses also exhibit advanced cognitive abilities related to the theory of mind, enabling them to understand interactions with other individuals. They can recognize a human being by their facial features, communicate with them through body language, and learn new skills by observing a person's behavior. Horses are also adept at categorizing and conceptual learning. In terms of working intelligence, horses respond well to habituation, desensitization, classical conditioning, and operant conditioning. They can also improvise and adapt to suit their potential rider. Understanding how horses' cognitive abilities function has concrete applications in the relationship between these domesticated mammals and human beings, particularly in terms of integrating learning capacity, which can improve their well-being, training, breeding, and day-to-day management.

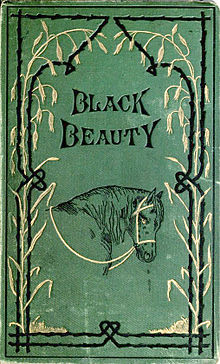

The horse's intelligence is perceived differently in different cultures; while the influence of Christianity may have led to it being viewed as limited, except for some medieval literature, it is more widely recognized among people who value animals as much as humans. This intelligence is portrayed in an anthropomorphized way in tales and legends about wise, talking horses, such as the Kyrgyz epic Er-Töshtük and the Russian tale of The Little Humpbacked Horse, but also in novels, films, comics, and series for young people, including The Black Stallion, Jolly Jumper, and Black Beauty.

History

The horse plays an important socio-economic role throughout history, working alongside humans in labor, combat, sports, therapy, consumption, and worship.[1][S 1][S 2] However, its own intrinsic qualities have often been overlooked, with many myths and legends surrounding it.[2][S 3] Humans were fascinated by horses long before their domestication, as early as prehistoric times, and the animal has inspired a wealth of written works since Antiquity.[S 4] Vanina Deneux-le Barh identifies a recurring theme in equestrian literature, both technical and literary: humans can train horses to become valiant fighters.[S 5] This suggests that horses, in their shared lives with humans, must utilize situational intelligence (or mètis, from the ancient Greek: μῆτις).[S 5]

Many equestrian authors have expressed their "desire to live with horses that are intelligent and committed to work".[S 6] Despite this, horses have historically endured significant cruelty.[S 7] The oldest known equestrian treatise written by Kikkuli of the kingdom of Mittani in the 14th century BC, is an instruction manual for the training chariot horses.[3] This text is characterized by its "ruthless" selection methods.[4]

Xenophon (430-355 B.C.), the first European author whose equestrian writings have survived, frequently discusses horses in his works.[S 8][S 9] He recognizes this situational intelligence in the warhorses of the city of Athens[S 10] and strongly advocates against the use of violence in training:

What a horse does by force it does not learn, and that cannot be beautiful, any more than if one wanted to make a man dance with a whip and a goad: ill-treatment will never produce anything but clumsiness and bad grace.

— Xenophon, On Horsemanship, Book IX[S 10]

From the Middle Ages to modern times

Most medieval technical literature consists of treatises on hippiatry, or veterinary care manuals.[S 11] Arab-Muslim civilization made significant contributions to the knowledge of equine medicine, education,[5] and training, thanks in part to the translator Ibn Akhî Hizâm, who wrote around 895,[6] and Ibn al-Awam, who advocated against violence and pioneered the application of habituation methods.[5]

There are anecdotal cases of horses portrayed as extraordinarily intelligent, such as the Catalan knight Giraud de Cabrières' horse, described by the medieval English chronicler Gervais de Tilbury as refined, invincible in races, capable of dancing, and even advising its knight. This horse reportedly helped its master achieve victories by communicating in a secret language.[S 12] Similarly, the English horse Marocco (born around 1586, died around 1606), nicknamed "The thinking horse" or "The talking horse", was trained and performed in public shows.[7][8]

Starting in the Renaissance, the printing press revolutionized the production and dissemination of equestrian literature.[S 11] These writings primarily focused on methods to achieve obedience and maneuverability in horses.[S 11] The Italian horseman Federico Grisone, however, promoted the use of physical punishment to control horses he considered too "clever".[S 7]

With the rise of philosophical debates in France, René Descartes' concept of the "animal machine" conflicted with Montaigne's perspective, which recognized animals as intelligent and virtuous beings.[S 13][S 14] Antoine de Pluvinel, influenced by Xenophon, acknowledged the sensitivity, individuality, and psychology of horses, emphasizing the importance of understanding "the brain."[S 15][9] François Robichon de La Guérinière (1733) also recognized a form of intelligence in horses, noting that some were "vicious" or "indecisive."[S 16] According to Sophie Barreau and zootechnician-sociologist Jocelyne Porcher, Guérinière was among the first to reject brutality, prioritizing the horse's cooperation over submission.[S 9]

In the 19th century

From the 19th century onwards, numerous equestrian treatises acknowledged and celebrated the intelligence of horses.[S 17][S 9] People who interacted with horses daily observed their ability to communicate and their sensitivity.[S 18] The era's fascination with animal intelligence was reflected in the organization of numerous horse-focused performances,[S 19] which became a feature of circus shows in the mid-19th century—most notably at Victor Franconi's circus, inaugurated in Paris in 1845.[S 20] In 1868, the Spanish writer Carlos Frontaura remarked on the "great intelligence" (gran inteligencia) of the horses pulling Parisian omnibuses, praising their initiative.[H 1]

François Baucher dedicated a one-and-a-half-page entry to the term "intelligence" in his Dictionnaire raisonné d'équitation (1833), where he declared his unwavering belief in the horse's intelligence:[S 17]

The horse has perception as it has sensation, comparison, and memory: it, therefore, has judgment and memory; it, therefore, has intelligence [...]

— François Baucher, Dictionnaire raisonné d'équitation[S 17]

The rational education system promoted by Baucher emphasized engaging with the horse's intelligence.[S 21] Similarly, zoologist Ernest Menault also recognized "signs of intelligence" in horses, though his observations leaned more toward poetic declarations than scientific evidence.[S 22] Gustave Le Bon was among the first to study horse psychology; his 1892 equestrian treatise acknowledged the horse's intellectual abilities.[S 21]

According to Jocelyne Porcher, 19th- and 20th-century zootechnicians applied the "animal machine" hypothesis to horses, drawing on the ideas of Descartes, Malebranche, and Bacon. This perspective denied that horses could think, feel pain, or possess consciousness and emotions.[S 18] Social pressure deterred researchers from challenging these notions for fear that their findings would be poorly received, as the "animal machine" concept was easier to defend in a context of industrialized farming practices.[10][S 18] In 1892, T. B. Redding reported in the magazine Science on a societal divide: some attributed intelligence and reason to horses, while others dismissed their actions as purely instinctual.[H 2]

Additionally, common misconceptions persisted. One of the most "preposterous", according to equestrian journalist Maria Franchini, was the belief—circulating since at least 1898—that a horse's obedience stems from seeing humans as seven times taller than they actually are.[11]

The worldwide popularity of "Learned Horses"

Until the mid-20th century, discussions about animal intelligence were framed through ontological comparison with human cognition.[S 23] In 1901, French military veterinarian Adolphe Guénon published a comparative psychology study titled L'Âme du cheval, where he described the horse as having a "rudimentary brain."[H 3] Starting in the late 19th century, there was a global fascination with so-called intelligent animals.[S 24] These "calculating" horses were equipped with specially designed tools—such as cubes, sticks, and boards—and demonstrated remarkable patience in performing their "feats".[S 25]

Manifestations of the "learned horse" craze

-

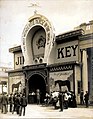

Beautiful Jim Key presented as an attraction at the 1904 World's Fair.

-

Entrance to the attraction around Beautiful Jim Kay.

-

Clever Hans performing with Karl Krall in 1909.

-

The mare Lady Wonder, photographed in 1940 for Life magazine.

-

Sign photographed in 1952, indicating Lady Wonder's ability to read minds.

Numerous journalists wrote articles about the intelligence of horses. In 1904, C. Mader questioned the notion of the horse as a "living machine";[H 4][S 9] in 1912, Remy de Gourmont commented on the growing fascination with horse intelligence in a society that had previously considered horses to be of average intellect at best;[H 5] and in 1913, a writer for The New York Times published an article asking whether horses were capable of "thinking".[S 26]

The case of Clever Hans (German: Kluger Hans) epitomizes this widespread interest.[H 5][H 6][12][S 21] This black horse, raised in Germany, became an international sensation in the early 20th century for his apparent ability to solve complex arithmetic problems by tapping his hoof to indicate answers:[13][14][S 1]

Crowds flock daily to the inner courtyard of Griebenow Street in northern Berlin, where his master puts him to work, to witness the extraordinary performance of the one who would henceforth be known as "Clever Hans".

— Vinciane Despret, Hans: the horse that could count[15]

Belgian philosopher Vinciane Despret notes the prolonged scientific debate sparked by Hans’s abilities, questioning whether horses possess conceptual intelligence.[16] German psychologist Oskar Pfungst later revealed that Hans was not actually calculating but was instead highly attuned to human body language, stopping his hoof taps when he detected subtle cues. This discovery led to the conceptualization of the Clever Hans Effect.[17][S 27][18]

Another notable example is Beautiful Jim Key, a "learned horse" who gained widespread fame in the early 20th century.[S 24] Similarly, the case of the mare Lady Wonder ignited a heated controversy about whether horses could communicate telepathically with humans.[S 28][H 7] Despite skepticism, some people continued to believe in equine telepathy well into the 1970s.[S 29][note 1]

Implications of the Clever Hans case for equine cognition research

Dutch primatologist and ethologist Frans de Waal highlights the relevance of Morgan's Canon—a scientific principle stating that animal behavior should not be attributed to higher mental faculties if it can be explained by simpler processes—as almost perfectly exemplified in the case of Clever Hans.[19] According to Jocelyne Porcher, Morgan's Canon had a lasting impact on research into animal cognition.[S 18]

De Waal also observes that the experiments on Hans were interpreted in ways that undermined his intelligence, despite actually showcasing his extraordinary ability to read and interpret human body language.[20] Ethologist Léa Lansade emphasizes that, at the time and up until the 1960s, animals were deemed "intelligent" only if they displayed human-like abilities—such as calculating or learning sign language—despite these skills being irrelevant to their natural behavior.[P 1]

The Clever Hans affair had a significant impact on subsequent studies of animal cognition, leading to the implementation of more rigorous experimental protocols.[21] As Deneux-Le Barh notes, "experimental sciences strive to avoid any intrusion of the mètis (cunning intelligence) of the individuals being studied."[S 30]

In the first half of the 20th century, research was largely dominated by behaviorism. Over time, this field divided into two main currents: ethology and cognitive animal psychology,[S 31] which eventually merged to form cognitive ethology.[S 31]

Highlighting the cognitive faculties of the horse

The behaviorist hypothesis that horses are mere "machines" reacting to stimuli has been thoroughly debunked, thanks in part to Maurice Hontang's Psychology of the Horse (1954) and subsequent scientific studies.[22] Early research in equine ethology began with Pearl Gardner in the 1930s,[23] where horses were initially tested under conditions similar to those for laboratory rats—using mechanisms that granted access to food. These experiments later became more sophisticated,[S 32] incorporating visual discrimination tasks and maze tests to evaluate learning abilities.[23]

Recent studies have demonstrated that horses do not simply follow "pre-programmed routines" but engage in cognitive processes to solve problems, showcasing genuine intelligence.[S 33] The number of scientific publications on animal intelligence has been increasing steadily since the 2000s,[S 18] particularly as cognitive ethology began including horses among its subjects of study.[S 34]

Knowledge still incomplete

Despite these advancements, much remains unknown about equine mental faculties. In 2022, psychologist and neuroscientist Michel-Antoine Leblanc observed significant gaps in research,[S 35] noting the limited number of scientific publications,[S 35] particularly before 2005.[S 3] Many earlier studies were anecdotal or speculative rather than systematic.[S 35]

Horses remain under-researched compared to other species. While primates have benefited from groundbreaking studies like those of Jane Goodall,[S 36] and dogs are the primary focus among domestic animals, equine cognition has received comparatively little attention.[S 37] In 2016, researchers Lauren Brubaker and Monique A.R. Udell pointed out that rat cognition studies outnumber those on horse cognition by a factor of seven.[S 38] The question of whether horses possess consciousness remains open for debate.[S 33]

In 2023, Éditions Quæ published the first book dedicated to the intelligence of working horses.[P 2][P 3] Jocelyne Porcher highlighted the unique insights offered by observing animals in work-related contexts, a field long overlooked by researchers despite its potential to reveal complex cognitive abilities.[S 39]

Definition of equine intelligence

Michel-Antoine Leblanc highlights the long-standing debate over equine intelligence, which has generated varied and often contradictory answers.[S 22][24][S 40] He notes that there is no singular or unambiguous definition of intelligence, particularly when applied to horses.[25][S 41] Historian and journalist Stephen Budiansky must first address the broader question of how intelligence itself is defined, as its meaning has shifted significantly throughout history.[26] Jocelyne Porcher and Sophie Barreau stress the importance of originality in behavioral responses as a hallmark of intelligence, distinguishing it from simple conditioned reactions.[S 40] Instinctual behaviors in horses, such as their strategies for avoiding biting insects or seeking cooler areas during hot weather, are sometimes mistakenly labeled as "intelligent."[27]

Modern interpretations of intelligence focus on the ability to solve problems,[26][S 23] establish relationships between elements, and assimilate new information, rather than merely demonstrating good memory.[26] Jocelyne Porcher underscores the subjective nature of these assessments, noting that horses possess "the intelligence that researchers are willing to attribute to them", as it is researchers who define the experimental conditions and cognitive tests.[S 36] As human evaluators, researchers inherently influence the interpretation of equine cognition, particularly in comparisons with other mammal species.[28]

To navigate these definitional challenges, some researchers, including Michel-Antoine Leblanc[S 42] and Léa Lansade,[29] focus on describing horses' cognitive processes without attempting to quantify their intellectual performance. Leblanc rejects efforts to measure an "IQ equivalent" for horses,[30] as well as attempts to determine whether horses are "more" or "less" intelligent than other species like dogs or cats.[30][S 43] Horses, having evolved as herbivorous prey animals, exhibit cognition and behavior that pose distinct scientific questions compared to carnivorous domestic species such as dogs and cats.[S 1]

Intelligence studied through interaction with humans

Among domestic animals, horses hold a unique position. Their modern domestic lifestyle contrasts sharply with their wild ancestors, while their intensive training for roles in sport, work, or companionship involves learning tasks far removed from their natural instincts—for instance, a movie horse learning to simulate death.[S 38][S 40][31] Beyond suppressing their innate flight responses in frightening situations, horses are trained to communicate and cooperate with humans, a species they might naturally associate with predators.[S 38][S 44][note 2] Authors like Alexis L'Hotte, François Baucher, Aloïs Podhajsky, and Nuno Oliveira emphasize that intelligence in equestrian work is deeply tied to affectivity and mutual understanding:[S 45]

Two living beings who are asked to collaborate harmoniously must understand each other to achieve a result.

— Aloïs Podhajsky, L'équitation[S 45]

A survey conducted in France by sociologist Vanina Deneux-le Barh, involving 800 professionals in the equestrian sector and published in 2021[S 46] and 2023, reveals that equestrian professionals often describe their horses as "partners".[S 47] These professionals highlight situational intelligence in horses, recognizing their ability to adapt and take initiative.[S 48] Notably, the mental demands placed on horses often correspond to the complexity of their tasks.[S 49]

Respondents also stressed the importance of rewarding horses to foster cooperation and nurture their intelligence.[S 50] Equine intelligence, in many ways, reflects the skills and methods of their trainers,[S 51] particularly when conditioning and positive reinforcement align with the horse's natural inclinations.[P 4]

Examples of mobilizing equine intelligence through interaction with humans

-

Learning the Spanish step with the help of a stick to give directions..

-

Training two circus horses in Russia.

-

Training a horse using clicker conditioning.

-

Training a young horse alongside an older, more experienced one.

-

Training a young horse for cattle work.

-

Mounted Cadre Noir horse, jumping a table.

-

Japanese horses trained in freedom.

The outcomes of horse-human collaboration underscore both the physical and cognitive investment of horses in their activities.[S 52] Deneux-le Barh describes equestrian disciplines as communities of practices that highlight the recognition of equine subjectivity and intelligence:[S 52]

Driving, dressage, western riding, and so on, are disciplines that require not only exceptional mastery of each movement but also a synthetic and immediate understanding of the messages of the driver or rider.

— De l'intelligence des chevaux [32]

Horses demonstrate intelligence through isopraxis—their ability to subtly perceive and respond to the movements of their riders.[S 53] Furthermore, studies on equine cognition suggest that familiarity with humans or other partners significantly influences the expression of a horse's cognitive abilities.[S 54]

Conditions of experience and limits

Like all mammals, horses construct their understanding of the world through sensory information.[33][S 55] However, their experience of the world differs significantly from that of humans.[34][35] Any evaluation of equine intelligence must therefore consider their unique perceptual capacities.[S 56]

Horses are not always studied under experimental conditions suited to their species.[36] Both Budiansky and Leblanc highlight that comparing the intelligence of different species often reflects cultural biases and fails to account for differences in sensory perception and physical capabilities.[36][S 57] For instance, while horses are sometimes deemed "less intelligent" than octopuses or equated with three-year-old children,[36][S 57] The octopus is very often cited as an example of an intelligent animal;[S 58] this comparison ignores the horse's lack of anatomical adaptations for manipulating objects, unlike octopuses:[37]

- Sniffing the lid

- Lifting the lid

- Opening the box

- Eating the food

Excerpt from the article "Do horses expect humans to solve their problems?", by C. Lesimple, C. Sankey, M. A. Richard, and M. Hausberger, 2012.[S 59]

Another major limitation in cognitive studies is the insufficient consideration of the horse's emotional state. Stress or discomfort significantly reduces performance in experiments.[38] Ethologist Martine Hausberger and her team underscore the impact of living conditions on cognitive outcomes: horses subjected to poor living conditions exhibit diminished cognitive abilities.[S 60]

Earlier studies—particularly those conducted before the 2000s—often overlooked the potential influence of prior learning on experimental outcomes.[S 61]

Although anthropomorphism has historically been viewed as inappropriate, it can sometimes aid in understanding horses' cognitive abilities by drawing comparisons with human behavior.[39] attributing human-like emotions and reasoning to horses—such as jealousy or premeditated malice—is inaccurate and risks oversimplifying their behaviors.[40]

Factors influencing cognitive performance in horses

Leblanc also points out that expressions of intelligence can vary greatly within the same individual and the same species,[25] for example depending on their preferences for social relationships or abstraction.[S 62] There is no evidence that horses dominant in the social hierarchy of their group are, in any way, more intelligent than other members of their group.[41] Young horses demonstrate more investigative behavior, with increased interactions with test devices compared to older horses, which could give them an advantage in learning contexts.[S 63][S 64] In addition to age, a lower hierarchical rank also seems to be one of the factors that fosters learning, particularly due to reduced neophobia.[S 64]

Breed differences

There are very few comparative studies on equine intelligence by breed, with Budiansky suggesting that the Quarter Horse may outperform the Thoroughbred.[42] This hypothesis aligns with the findings of Lindberg et al., who propose that so-called cold-blooded horses (ponies and draft horses) complete conditioning tasks faster than warm-blooded horses (such as the Thoroughbred and the Arabian).[S 63] In 1933, L. P. Gardner concluded that the Belgian Draft horse learned tasks more quickly than the Percheron.[H 8]

Many older[H 9] and more recent[43][44] studies describe the Arabian as a more "intelligent" horse compared to other breeds. This is exemplified in The Illustrated Horse Management by Edward Mayhew, published in 1864:[note 3]

The Arab horse is undoubtedly the most beautiful and the most intelligent specimen of its race.

— The Illustrated Horse Management, preface p.VI[H 10]

French veterinarian Alexandre-Bernard Vallon (1863) considered oriental horses, such as the Arabian and the Barb, to be more intelligent than those of "common breeds."[H 11] Maurice Hontang notes that the Arabian and the Thoroughbred have been bred for their "love of fighting" and competition, which might explain their psychological differences.[H 12]

The Horse's Brain

As in all large mammals, the horse's brain acts as the "conductor" of its nervous system, orchestrating all perceptions to enable the animal to respond to them.[S 65] The brain, which is longer than it is wide, has an ovoid shape and features numerous tightly packed gyri.[S 66] A series of experiments suggests that the right cerebral hemisphere is more specialized in communication signals, while the left cerebral hemisphere is more focused on the categorization of stimuli.[S 67]

The brain of an adult horse weighs approximately 510 grams;[S 68] however, this weight relative to body size is not a significant factor in measuring intelligence.[S 69] The encephalization coefficient is 0.9%.[45]

Cognitive abilities of horses

As riding instructor Nicolas Blondeau observes, a horse possesses learning and adaptation abilities comparable to those of a human.[22] Training enables it to acquire skills.[22] Horses display intelligence in solving a various daily tasks, such as finding food and managing social interactions.[P 5] Discriminative learning is a crucial area to assess in order to understand horse cognition, as it provides insights into their abilities at the species level and sheds light on other cognitive domains.[S 70]

| Capacity or aptitude | State of knowledge | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Self-awareness | To be studied further. Not demonstrated by the mirror test. | [S 71][S 24] |

| Theory of mind | Proven for the attribution of certain mental states, beginnings of proof for the attribution of attentional state (Trösch et al. 2019); to be explored. | [46][P 6][S 72][47] |

| Emotional contagion | Some evidence (Trösch et al. 2020). Emotional contagion between horses remains to be studied. | [P 7][48][S 73] |

| Assigning a reputation | Proven. | [P 8][S 75][S 76][48] |

| Referential communication (movements to attract attention) | Some evidence. | [S 75][46][S 77] |

| Mental representation | Proven, sense of direction only mentioned by anecdotes. | [S 78][49] |

| Long-term memory | Proven (Hanggi and Ingersoll 2009), up to ten years. | [S 79][S 80][50] |

| Working memory | Low, about twenty seconds. | [S 81][51] |

| Short-term memory | Proven (Hanggi 2010), about thirty seconds. | [52][S 82][S 83] |

| Categorization | Proven. | [S 84][S 85][53][S 86][S 87] |

| Enumeration | Controversial, perhaps an ability to count to four. | [54] |

| Object permanence | Failure (a study). | [S 88] |

| Telepathy | Supported by Henry Blake[S 29][55] and Rupert Sheldrake,[56] always mentioned by testimonies,[P 9][P 10] never demonstrated. | [57][H 7] |

The ability to learn conspecifically (by observing other horses) was long unknown,[S 89] until it was demonstrated in 2008.[S 90][S 91][S 64]

Horse problem solving performance

Domestic horses, which live in artificial environments that suppress their instinctive behaviors while learning unnatural tasks, are generally more adept at solving complex problems than wild horses.[S 3]

According to Budiansky, horses are not particularly skilled at problem-solving.[58] Most carnivores, as well as primates, perform better, especially when avoiding obstacles placed in their path.[58] He hypothesizes that this average performance stems from fundamental differences between carnivores and herbivores like horses.[58] A herbivore does not anticipate the reactions of its prey. However, veterinarian Robert M. Miller argues that the horse is "intelligent enough to quickly choose between two evils."[S 92]

Ethnologist María Fernanda de Torres Álvarez, on the other hand, believes that working relationships enable the horse to harness its intelligence to find practical solutions for accomplishing the tasks it is asked to perform.[S 93] She cites the example of Camargue horses ridden by volunteers for cattle work, which can independently correct their rider's mistakes to catch fleeing bulls.[S 94] Beginner riders are often paired with mature horses that can compensate for their mistakes.[S 95] Similarly, Camargue horses used on treks by inexperienced tourists know how to anticipate the errors of these novice riders.[S 96] For María Fernanda de Torres Álvarez, the horse's intelligence is demonstrated through its ability to independently find solutions to problems.[S 97]

Horse performance in maze tests

According to Budiansky, horses perform respectably, though not exceptionally, in most maze tests.[59] These tests typically involve a "T" or "Y" shaped maze with two choices: one leading to a dead end and the other to access food, water, or social contact with other horses. The horse cannot see what lies at the end of either branch of the maze in advance.[59][S 98] The learning performance of horses subjected to this test is comparable to that of tropical fish, octopuses, and guinea pigs.[59] In the experiment cited by Budiansky, even after five trials, 20% of the horses still made mistakes in finding the exit.[59]

Maria Franchini uses the maze test to illustrate bias: while rats perform better than horses, rats are subterranean animals accustomed to moving through confined spaces. In contrast, wild horses live in large, open environments.[38]

Memory

The excellent memory of horses is one of the few conclusions agreed upon by both 19th-century horsemen and modern researchers.[60][S 53][S 99][S 100] In 1892, the sociologist Gustave Le Bon wrote:

The fundamental characteristic of the horse's psychology is memory. Not very intelligent, it seems to have a representative memory far superior to that of man.

In the equestrian world, there are numerous accounts of horses remembering people who mistreated them, even years later.[61] However, Michel-Antoine Leblanc observes that scientific research has historically been limited, and the consensus around horses’ excellent memory was largely based on anecdotal evidence.[S 79][60]

Dr. R. M. Miller theorized in 1995 that horses possess excellent memories due to their evolutionary history, but he did not provide supporting evidence.[S 101] In 2009, a study by Evelyn Hanggi and Jerry Hingersol offered the first evidence of long-term memory in horses, showing that they could retain complex memories—such as learning rules and performing mental tasks—for up to ten years.[S 79][S 80][50] Horses also remember the people they interact with, recalling both positive and negative past experiences.[S 38] Ethologist Marthe Kiley-Worthington reported training two horses from a young age to understand around two hundred words.[62]

When horses were exposed daily to an arena with new objects, they demonstrated that they could remember inspecting the same object earlier that day but would re-explore it on subsequent days.[S 102]

(A) A horse mounted at the midpoint between two plates containing droppings approaches the right plate and sniffs the target.

(B) About 5 minutes later, the horse is presented with a second choice and chooses the left target.

(C) About 5 minutes later, the horse is presented with a third choice and walks past the previous two targets without examining either.[S 103]

Regarding short-term memory, horses are average compared to other mammals such as donkeys, cats, and dogs, retaining information for at least 30 seconds.[52][S 82] Their short-term memory is particularly strong when exploring new objects.[S 83] However, their working memory is limited, lasting about twenty seconds.[51] Lansade attributes this to the lack of necessity for extensive working memory in grazing herbivores.[63]

Spatial visualization

Despite misconceptions about their visual perception,[S 104] horses have eyesight adapted to life in open environments.[S 105] While they do not see sharply[S 56][S 106] and their color perception is dichromatic,[S 107][S 108] horses excel in spatial visualization.[P 5] This is logical since sight plays a key role in their social interactions.[S 105] Their ability to navigate suggests they rely on a cognitive map of their surroundings.[S 109]

Horses perform well on spatial (3D)[S 104] visual discrimination tasks but struggle more with 2D object discrimination, such as patterns on colored backgrounds.[S 110] There is no scientific basis for the myth that horses need to see an object with both eyes to recognize it,[S 111][S 112] as part of the optic nerve fibers from each eye connected to the opposite hemisphere of the brain.[S 112]

Hanggi provides numerous examples of horses noticing changes in their surroundings, such as objects being moved.[S 104] Their reactions to such changes highlight their ability to recognize alterations in their visual environment.[S 111] This skill applies to both concrete objects like toys or doors and abstract ones like patterns or figures.[S 111] In contrast, experiments on object permanence indicate that horses struggle to track objects once they become invisible.[S 88]

Maria Franchini speculates that some horses perceive insects or small animals in their path, noting a mare who avoided live insects but stepped on dead ones.[64] Finally, many anecdotes from riders describe a strong sense of direction in horses, which psychologist Sara J. Shettleworth suggests is heavily reliant on memory.[49]

Counting and categorizing

Horses are capable of solving advanced cognitive problems, including categorizing and understanding concepts.[S 84][S 85] Researcher Evelyn Hanggi demonstrated that horses can grasp the relational concept of size by sorting objects of different dimensions.[53][S 86] Horses can also distinguish complex patterns, such as certain geometric shapes, and are particularly adept at recognizing triangles.[S 87]

Studies on horses' ability to count recall the famous case of Clever Hans, as it remains unclear whether horses possess a genuine ability to count.[65] Some research suggests that horses can differentiate between one apple and two, or two apples and three, but not between four and six apples.[66] This implies they can "count" up to four.[P 11]

These studies also show that horses can form mental representations and perform simple counting tasks.[66]

An ability to improvise?

Based on practical experiences, Doctor of Theatre Studies Charlène Dray suggests that show horses are capable of improvising on stage without expecting a reward, provided they have exploratory objects available.[S 113] However, several riders who work with show horses agree that these animals are not conscious of creating artistic emotions.[S 24]

Shelly R. Scott describes a similar practical example, involving a horse race for where neither the horses nor their riders were prepared, requiring both to improvised during the event.[S 114]

Social intelligence of the horse

Many studies have highlighted horses' advanced social intelligence.[P 7][S 75][S 115][67] According to Lansade, in roughly ten years, scientific research on horses' social cognition toward humans has yielded significant discoveries, particularly in the late 2010s.[68] The findings demonstrate that horses "have a rich and complex representation of the individuals they interact with."[S 54] These results also position horses as strong candidates for studies on the theory of mind.[S 90] Such social learnings are part of their complex learning capabilities.[S 116]

In the wild, horses live outdoors in groups and learn from one another within these social structures.[S 63][S 61] This social learning is influenced by hierarchy, as horses are more likely to learn from dominant members of their group than from subordinate members or those outside the group.[S 91] Visual social communication predominates among horses but is more challenging to study compared to species that rely on sound-based communication.[69] Horses can even experience emotional contagion, as demonstrated when they respond to films.[P 7][S 74]

When working with humans, horses naturally seek cooperation, calmness, and avoidance of conflict.[S 117] They are capable of interpreting human body language,[P 12] reading human emotions, and attributing mental states to humans.[S 75] Maria Franchini gives the example of a horse distinguishing between a helpful gesture, such as swatting an insect on its body, and an aggressive one, such as attempting to hit it, to which the horse reacts by rebelling or fleeing.[70] An Icelandic study on two groups of 22 and 24 horses found that those exposed to a peer's visual demonstration did not outperform control animals in solving spatial maze tasks, indicating that social learning failed in this context.[S 118]

Recognition of other horses and humans

Horses can recognize individual humans (and one another)[S 109] from simple auditory cues, such as a voice, or visual facial features like facial recognition.[S 54][P 13][71][72] Experiments have shown that horses can discriminate between faces in photographs or films[S 36] and associate these with real individuals.[71] Remarkably, horses can even differentiate between photographs of identical twins.[S 119][71] They also remember familiar faces they haven't seen for six months and can recognize them in photos.[71][S 120][73] It appears that horses recognize faces holistically, as humans do, perceiving them as a whole rather than focusing on individual features.[71][74] Lansade emphasizes the "impressive" nature of this discovery, describing it as interspecific recognition: for comparison, a human accustomed to cows might struggle to distinguish individual cows, whereas most horses tested can differentiate human faces flawlessly within days. [73]

Horses are also able to differentiate between human voices and link a voice heard through a speaker with the person when they hear it in real life.[71] They associate voices with past experiences, whether positive or negative.[S 121] Horses can recognize emotions expressed through human facial expressions and vocalizations and respond accordingly.[S 122]

Finally, horses have an intermodal mental representation of both their peers[S 123] and humans,[S 124] associating faces, smells, voices,[71][S 125][S 126] and expectations based on past experiences.[S 124] Horses deprived of one sense likely compensate by relying on their other senses to recognize individuals.[S 125]

Interspecific communication

Horses can communicate interspecifically with humans when they feel the need to do so.[P 14][S 127][S 75] They are capable of attracting attention to gain access to a food source, including by using their gaze and, in some cases, making physical contact.[S 127][S 128][S 129][75] The horse is the second domestic animal species, after the dog, in which this ability has been demonstrated.[S 130] Horses seem more interested in humans when they expect humans to provide them with food,[S 59][S 72] and the training technique used influences their interspecific learning abilities. Training that applies ethological principles yields better results.[S 131]

A study revealed a "symbolic communication primer" between humans and horses, enabling horses to express their preference for wearing a blanket or not.[S 132] According to the 2016 study, horses can learn the meaning of symbols through positive reinforcement (one symbol for putting on a blanket, one for staying as they are, and one for removing the blanket) and then use those symbols to communicate their preferences to a human.[S 133][S 134]

In interspecific communication, horses can take into account a human's perspective. When faced with two people, only one of whom knows where food is hidden and inaccessible to the horse, the horse will instinctively ask for help from the person it knows can access the food.[P 7][46][S 72] This ability, considered complex, was long thought to be exclusive to large primates and dogs.[P 7]

Experiments on horses’ sensitivity to human pointing gestures (e.g., pointing at an object containing food with a finger) concluded that horses value these gestures, though it remains unclear whether they interpret them as communicative signals directed at them.[S 135] Four distinct pointing methods were tested; horses excelled in all tasks except for distal dynamic-momentary pointing, which is significantly more cognitively demanding than the other styles.[S 136]

Horses are sensitive to human attention and are more likely to approach a person who is looking at them while feeding them than one who is not.[S 137][S 138] Young horses do not appear inherently predisposed to recognize or respond to human attention, suggesting they acquire this skill later through learning.[S 139][S 140]

Interspecific learning

Horses can also acquire new skills simply by observing humans.[S 141][S 142]

In one experiment, humans demonstrated to horses how to press a button to open a feeder, while another group of horses did not witness a demonstration. A few horses learned to open the feeder through observational conditioning, but most learned socially by observing humans to understand where and how to manipulate the opening mechanism, subsequently using trial-and-error to access the food. [S 141]

This ability to learn interspecifically may help explain why domestic horses can figure out how to open their stall doors or even operate the handle of an electric fence.[P 15]

Reputation attribution

The horse can attribute an emotional valence (a reputation) to a human based on its own experience, as well as its observations of interactions between an experimenter and another horse.[S 75][S 76] Lansade explains this ability by noting that many horses react to the arrival of a veterinarian, even one they have never encountered before. This seems to demonstrate an ability to recognize attributes specific to this profession (such as clothing or a particular smell) and to associate them with past experiences.[76] In Lansade's cited experiments, horses remember up to a year later being groomed by a person who gave them either a pleasant or unpleasant experience. They even adopt characteristic facial expressions in anticipation, before this person begins grooming them.[77] Horses can also recognize, in a film, a person who provides a positive or negative experience to one of their peers, and they adjust their interactions with these individuals based on the information observed in the films.[78]

Applications of knowledge of equine cognition

Throughout its life, a horse is required to learn new skills, whether for survival and adaptation to its environment or for human purposes.[79] From its historical roles in warfare and agriculture to its modern uses in sports and leisure, learning remains essential.[80] Breeding and selection practices have not eliminated the need for this learning.[31] The entire horse industry is built upon the animal's ability to learn under human guidance.[S 143]

A wealth of literature exists on various methods for training horses for riding, as well as on the diversity of training approaches that can be applied.[S 38][S 144][81] The horse's social intelligence is also utilized in "equicoaching" sessions, which aim to help humans "reconnect with their emotional intelligence."[82]

Learning, however, is a complex and multifactorial process that requires time and commitment. Horses respond best to short, frequent training sessions.[S 145][83] Other influential factors include genetics, motivation, and the horse's mood.[S 146] An individual horse's temperament also plays a role in its learning abilities, with calmer, less emotional horses tending to learn more quickly.[41] Personality may further influence how a horse responds to different experiences.[P 4]

Understanding the horse's cognitive abilities allows for practical applications to better integrate its learning capacity. This, in turn, facilitates relationships between horses and humans and can improve the horse's well-being, training, breeding and daily care:[S 27][S 147]

However, many horses still live in conditions unsuitable for their cognitive and emotional needs, such as in stalls without social contact, in darkness, in dusty environments, and without mental stimulation.[S 148] The use of inappropriate punishments remains widespread, as theoretical advancements in understanding horse behavior are not always accompanied by changes in practical training methods.[S 149]

Responses to conditioning

The often overused concept of "conditioning" refers to the association between a stimulus and a response (which can lead to habitual behavior), and does not suggest that the conditioned subject is like a machine.[84] Simple conditioning can be voluntary (a classic example being the training of circus horses)[85] or involuntary, such as horses that become agitated and neigh at mealtime because they have associated a specific time or a noise in a food storage room with the impending arrival of their food.[S 150][86]

A series of practical experiments show that horses respond very well to simple forms of learning, such as classical conditioning (or Pavlovian conditioning) and operant conditioning.[S 3][S 38] These results are logical since these techniques (rewarding or removing a constraint after a successful task) are commonly used by humans to train horses to perform expected tasks.[S 3] Reinforcement can be positive or negative.[S 151][87] At the beginning of reinforcement learning, the horse is unaware of what is expected of it and gives random responses. It is the consequence of the response (reinforcement or punishment) that enables learning.[88]

Examples of positive and negative reinforcement and punishment in horses

-

Positive reinforcement: the horse receives a reward in the form of food immediately after exhibiting the desired behavior.

-

Positive punishment: This horse feels the unpleasant pressure of his halter behind his ears because he does not follow the movements of the man holding the lead rope of his halter.

-

Positive punishment: a horse that touches this fencing tape will receive a mild electric shock, dissuading it from doing it again.

-

Negative punishment: this grooming, a pleasant moment for the horse, can be interrupted if it exhibits undesirable behavior.

In practice, horse professionals use negative reinforcement more frequently than positive reinforcement.[89]

The use of chaining can also be useful,[S 152] for example, to teach complex movements, such as the curtsy, step by step.[S 153] Regardless of the reinforcement method used to train a horse, it is important to apply consistent techniques over the long term and to avoid mistakes during the learning process, particularly due to the horse's memory capacities.[S 154][S 99] Lansade cites the example of a horse that knows how to get rid of its rider by leaping over it, and "will never forget that it has mastered this technique." The only way to extinguish this type of behavior is for the horse to discover that "it no longer has the desired effect."[90] The conditioning response also implies that "any bad start permanently compromises future success."[91]

Positive reinforcement learning

Of all the operant conditioning techniques used with horses, the most effective is positive reinforcement,[S 155][92][93] even when applied to horses that bite.[S 156] However, this effectiveness largely depends on maintaining a clear link between the desired behavior and the reward: the reward must be given immediately after the successful completion of an exercise.[S 155][94] At first, an incomplete response can be rewarded (for example, a simple weight transfer onto the hind limbs in a horse learning to back up).[88] Then, increasingly complete responses are required before rewarding (in the case of backing up, this could be one step back, then two steps back).[88]

Once positive reinforcement learning is mastered, rewards become less frequent, but it is important to continue soliciting this learning from the horse regularly to prevent its extinction.[S 154][83]

Care must be taken not to inadvertently reward unwanted behaviors. A classic example is the horse that taps on the door of its stall out of boredom, which a person inadvertently reinforces by raising their voice at it until it stops tapping.[95] In the horse's perception, having managed to attract the attention of a human may be seen as positive reinforcement, increasing the likelihood it will tap on its door again to seek attention.[89]

Negative reinforcement learning and punishment

Negative reinforcement learning in horses should never involve intentionally inflicting pain but rather temporarily placing them in an uncomfortable situation (for example, making them feel pressure behind their ears with a halter) until they voluntarily change their behavior to regain comfort (in this example, by following the movement of the person holding the lead rope of the halter).[S 157][S 149] Negative reinforcement appears to be very effective in training foals, but it can also increase their stress response.[S 158] When negative reinforcement occurs spontaneously (such as a horse touching an electric fence), it can result in long-term memory of the experience.[S 154] This is why some horses panic at the sight of a syringe: they associate the sight of the syringe with the pain of the subsequent injection.[S 154] If a horse's defensive behavior is associated with the termination of a request (e.g., a request to remain calm during an injection or clipping), the animal learns that its defense results in the cessation of the request, which may cause it to become uncontrollable by humans.[96] Horses can thus systematically adopt threatening behavior towards their veterinarian.[96]

According to Australian researchers Paul D. McGreevy and Andrew N. McLean, the misuse of negative reinforcement can lead to learned helplessness or neurosis.[S 149] It can be difficult for horses to make the connection between the behavior being punished and the punishment.[89] If they are whipped after refusing to jump an obstacle, they may not associate the blows with the refusal and may develop an aversion to the show jumping arena, or even to being ridden or to the person who punished them.[97] A horse can also become "jaded" by harsh and inconsistent stimuli, making it insensitive to more subtle cues from a potential rider.[88] This means that before punishing a horse, it is always necessary to consider whether there has been a miscue.[98]

Trial and error learning

Horses are also capable of learning through trial and error, such as those that discover how to use large balls (by initiating a gentle push on the side of the ball) after unsuccessfully trying to jump on them.[S 159] They may also learn how to operate an automatic waterer or accidentally figure out how to open the door of their stall after playing with the latch.[85] In the latter case, if the horse discovers its freedom of movement and access to food, positive reinforcement follows, increasing the likelihood that it will attempt to open the door of its stall again.[85]

Responses to non-associative learning

Horses also respond well to habituation and desensitization,[S 160] which are two forms of non-associative learning.[99]

Habituation

Habituation is a common learning process among all animal species. It allows the horse to filter perceptions in its environment by no longer associating them with potential dangers (for example, plastic bags flying or ropes floating above its head).[S 161][99] The response to the stimulus gradually disappears.[99] This type of learning is particularly important for foals or adult horses placed in a new environment, as it helps them get used to noises, human touch, and the sight of unusual objects.[100] For example, letting the horse hear the sound of clippers during feeding can significantly reduce its fear reaction when the clippers are used on its neck and poll.[101]

An extreme form of habituation, called "behavioral imprinting," has been tested on foals. called "behavioral imprinting," This involves intensive handling immediately after birth, including inserting fingers into natural orifices (mouth, ear, and anus), supposedly to produce horses that are easier to train and handle as adults.[102] However, its intrusive nature and conflicting results have led many scientists to discourage its use.[103] Some breeders use it to accustom foals to the presence of humans and dogs at a young age.[S 159]

Desensitization

Desensitization involves regularly exposing the horse to a stimulus that triggers a reaction until the reaction is extinguished.[S 162] A classic example is opening an umbrella, which typically triggers a stress reaction, such as an increased heart rate. After about ten repetitions of opening the umbrella, the desensitized horse usually no longer reacts with stress.[101]

The opposite of desensitization, sensitization, can result from mistreatment, such as a horse developing a strong reaction to a person who has caused it pain in the past.[101]

Controversies and preconceived ideas

PhD in animal behavior biology Evelyn B. Hanggi and sociologist Vanina Deneux-Le Barh emphasize the persistence of beliefs that attribute limited abilities to horses. These beliefs postulate, for instance, that horses react only by instinct or respond solely to conditioning, without demonstrating cognitive abilities.[S 3][S 163] One of the most frequently cited fallacious arguments is that intelligence is incompatible with being ridden or mistreated by humans, even though mistreatment also occurs between humans without being caused by reduced intelligence.[104]

These misconceptions still prevail in professional equestrian circles.[S 3][S 163] The results of the Deneux-Le Barh survey (2021) reveal significant ambivalence in the perception of intelligence in working horses. Some breeders and users believe that responses to conditioning are merely the reproduction of behavior, even though their statements reveal the horses' mètis (ingenuity or craftiness).[S 163] Leblanc cites as an example many riders who "deny any intelligence in the horse" while simultaneously attributing complex mental processes to it, using anthropomorphic phrases such as "he did it on purpose to annoy me."[24] Linda Kohanov shares that, according to the American cowboys she interviewed, horses are not intelligent enough to recognize their own names.[105] Equestrian journalist Maria Franchini also reported in 2009 frequently hearing claims about horses' very low intellectual capacities, whether in stables or major media.[28]

Memory and empathy, on the other hand, are better recognized in professional circles,[S 163] as illustrated by stories of horses adapting to work with disabled individuals, such as in equine therapy.[S 164]

Invited to the show La Tête au carré on October 3, 2007, geneticist Axel Kahn asserted that horses possess much more limited intellectual capacities than octopuses, primates, and cetaceans. He cited the example of a mirror test where horses attacked the mirror placed in front of them.[106] Maria Franchini lamented that this statement, made on a popular program, could have fostered misconceptions.[38] Leblanc notes that the mirror test alone (or the Gordon G. Gallup test)[S 23] may not be sufficient to confirm or deny a species' self-awareness.[S 165] He references a 2017 study by Paul Baragli and his colleagues, in which horses subjected to the mirror test displayed clear signs of distinguishing between what they saw in the mirror and a real animal. However, there were no indications that they recognized themselves in the mirror.[S 166]

In culture

Mythology, legends and tales

Some stories from mythology, legends, and folktales depict horses as extraordinarily intelligent. The Scythian features many fabulous horses, including the kokcwal, aquatic descendants of the sea god's horses, capable of understanding human speech.[S 167] Bucephalus, the horse of Alexander the Great, is described in Greek sources and the Alexander Romance as "very intelligent," much like his young master, particularly because he, too, understands human speech.[107] In the Turkish epic of Er-Töshtük, a folktale from Kyrgyzstan, the horse Tchal-Kouyrouk warns his rider, Töshtük, with these words: "Your chest is broad, but your mind is narrow; you think of nothing. You do not see what I see, you do not know what I know... You have courage, but you lack intelligence."[108] The psychopomp powers of the horse are portrayed as superior to those of humans.[109]

Medieval Christian literature features numerous "extraordinary horses" endowed with intelligence and human-like qualities.[S 168][S 169] Professor of medieval literature Francis Dubost cites examples such as Bayard,[S 170] the horse from the lai of Lanval,[S 171] and The Song of the Aliscans.[S 12] Even the horses of pagans are depicted as possessing formidable intelligence, capable of fighting independently.[S 172] The medievalist Michel Zink also observes the presence of faithful horses in this literature, which "demonstrate an intelligence that exceeds their nature." Examples include La Chevalerie d'Ogier, the Broiefort d'Ogier, and the Marchegai d'Aiol.[S 169]

Italian ethnologist Angelo De Gubernatis identifies a mytheme—[note 4] the transformation of a fool into an intelligent and wise man—as parallel to the transformation of a worthless nag into a noble horse:

The hero's horse, like the hero himself, begins by being ugly, deformed, and unintelligent, and ends by becoming beautiful, brilliant, heroic, and victorious.

— Angelo De Gubernatis, Zoological Mythology[H 13]

De Gubernatis cites, among other examples, the Russian tale of The Little Humpbacked Horse, in which a small horse gifted with the ability to fly repeatedly saves its rider and wisely advises him:[H 13]

The Dogon tale "Why Doesn't the Horse Speak?" explains that in the past, horses spoke with humans, but an ungrateful and deceitful woman exploited the advice of a clever horse without thanking him or informing her family of his help. In retaliation, all horses stopped speaking to humans, choosing instead to neigh.[110]

The Mahi tale (central Benin) titled Destiny, tells of an orphan abandoned by his brothers who spares three horses destroying his crops and gains their help to win the love of a princess.[111]

In the Aarne-Thompson-Uther classification, these tales correspond to the ATU 531 type tale, "The Intelligent Horse."[S 173] This theme is also found in the Norwegian tale Dapplegrim,[112] the Sicilian tale Lu cavadduzzu fidili (The Loyal Horse),[113] the Guatemalan tale of the "Bad Combadre,"[114] and the medieval Jewish tale "Joḥanan and the Scorpion," one of the seven stories from the Sefer ha-ma'asim.[S 174]

Religious and cultural particularisms

Professor of religious studies Judy Skeen emphasizes the importance of questioning the "concept of human domination over nature" to move beyond the view of animals as "mere functions or resources for humans" and to challenge the assumption "that human beings have more value than other creatures." She advocates for evaluating intelligent life using criteria beyond human intelligence.[S 175] She also highlights a contrast between the perception of the horse's intelligence in Christian tradition, which assigns greater value to humans than to horses, and in other traditions, such as Native Americans beliefs, which readily acknowledge animal intelligence—for example, through observations of prey-predator relationships.[S 175]

Christianity

According to historian Éric Baratay, the refusal to recognize animal intelligence was largely adopted[note 5] by Western Christianity, drawing on Platonist and Aristotelian philosophies to elevate humans while diminishing and devaluing animals.[S 176]

Through Germanic pagan beliefs, historian Marc-André Wagner explores a progressive demonization of the horse, aimed at Christian leaders ending the ritualistic reverence once afforded to the animal.[S 177] He specifically mentions the fight against hippomancy (divination using horses), wherein evangelists countered pagan claims that horses possessed divinatory powers by asserting instead that it was the Christian God speaking through the animal.[115] Wagner cites the example of the 7th-century text Vita de Columba of Iona, in which the Irish saint's horse lays its head on his knees and begins to weep, apparently sensing its imminent death:[115]

To this crude and irrational animal, in the manner he chose, the Creator revealed in a manifest way that his master was going to leave him.

— Adamnan von Hi, Vita S. Columbae, III, 23

In Ladakh

According to S. C. Gupta et al., Tibetans in the cold, arid region of Ladakh believe that the intelligence of their small local Zanskari horses enabled warriors to achieve superior performance in regional wars during the 18th century.[S 178]

In Mongolia

Anthropology lecturer Gregory Delaplace (2015) notes that the Mongols regard horses as companions and recognize not only their intelligence (uhaan) but also their ability to perceive and feel the invisible—a quality independent of intellect.[P 16] The Mongolian historian Françoise Aubin provides an example in the Mongolian phrase used to inquire about the best gait for a horse, "ene jamar erdemtej mor' ve," which literally translates as "What is its science?" or "What is its art?"[S 179]

Literature, film and television

The satirical novel Gulliver's Travels (1721) features noble, rational, and intelligent horses called the Houyhnhnms. According to literature professor Bryan Alkemeyer, its author Jonathan Swift may have intended to prompt a reevaluation of the definition of humans and their supposed superiority over animals.[S 180] The Mearas imagined by J. R. R. Tolkien, include Grippoil, Gandalf's mount, a type of highly intelligent horse capable of understanding human language. These horses are said to be descended from Nahar, the steed of Oromë.[116]

Professor Sylvine Pickel-Chevalier and Dr. Gwenaëlle Grefe identify an archetypal model of the horse in children's and youth literature and cinema, which they call "horse-love." Representative examples include the cultural productions surrounding The Black Stallion, White Mane, Black Beauty, Running Free, the novels, films, and series of My Friend Flicka and War Horse, as well as the films Spirit and Whisper.[S 181]

In this type of narrative, which centers on a story of mutual affection between a human protagonist, often a child, and an equine companion, they note that the horse, "elevated to the rank of an epic hero to the point of sometimes becoming the narrator," is distinguished by physical and behavioral traits, including intelligence.[S 181] However, the portrayal of the horse's abilities often includes a strong dose of anthropomorphism.[S 181]

After all, maybe the stallion didn't enter the park and is hiding in some corner of the city? ... But no! Black is much too intelligent to stay in the streets!

In his children's book The Learned Horse (1991), Laurent Cresp tells the story of an intelligent horse living in Istanbul, who wishes to be treated like a sentient being.[P 17]

In comics, Lucky Luke's mount, Jolly Jumper (created in 1946) is depicted as the most intelligent horse in the West. He is capable of speaking (and even engaging in philosophical discussions), counting, writing, playing chess, and fishing on his own.[118] Similarly, the American television series of the 1960s Mr. Ed, the Talking Horse features a horse that speaks only to its owner, who has a fondness for drink. The intelligence of the horse actors in the series has often been praised.[S 182]

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ This is particularly the case of Henry Blake, in his work "I speak to horses... They answer me."

- ^ The hypothesis of a human assimilation to a predator from the point of view of the horse is controversial. Hominids are not a family of mammals known to have large predators.

- ^ This book was reprinted around ten times at the end of the 19th century.

- ^ The notion of mytheme was defined later by Claude Lévi-Strauss.

- ^ When Constantine imposed Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire, Christians represented only 4 to 5% of the total population of the Empire (Robin Lane Fox, Pagans and Christians: Religion and Religious Life in the Roman Empire from the Death of Commodus to the Council of Nicaea, Presses Universitaires du Mirail, 1997).

References

- ^ Blondeau (2023, pp. 5–6)

- ^ Franchini (2009, p. 7)

- ^ Gouraud, Jean-Louis (2018). "Kikkuli". Le tour du monde en 80 chevaux: Petit abécédaire insolite [Around the world in 80 horses: An unusual glossary] (in French). Actes Sud Nature. ISBN 978-2-330-10203-6.

- ^ Fagan, Brian (2017). La Grande Histoire de ce que nous devons aux animaux [The Great Story of what we owe to animals] (in French). La Librairie Vuibert. p. 198. ISBN 978-2-311-10212-3.

- ^ a b Lansade (2023, pp. 25–26)

- ^ Lignereux, Yves (2003). Une Bibliographie hippiatrique pour le Moyen-Âge [A Hippiatric Bibliography for the Middle Ages] (in French). Vol. 46. Bulletin du centre d’étude d’histoire de la médecine. p. 11. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ Stollznow, Karen (2014). "Talking Animals". Language Myths, Mysteries and Magic. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 165–178. doi:10.1057/9781137404862_17. ISBN 978-1-137-40486-2.

- ^ Bondeson, Jan (1999). "The Dancing Horse". The Feejee Mermaid and Other Essays in Natural and Unnatural History. USA: Cornell University Press. pp. 1–18. ISBN 0-8014-3609-5.

- ^ Lansade (2023, p. 26)

- ^ Franchini (2009, p. 8)

- ^ Franchini (2009, pp. 12–13)

- ^ De Waal (2018, pp. 65–68)

- ^ Franchini (2009, pp. 212–213)

- ^ De Waal (2018, p. 66)

- ^ Despret (2015, p. 14)

- ^ Despret (2015, pp. 120–121)

- ^ De Waal (2018, pp. 66–67)

- ^ Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, p. 289)

- ^ De Waal (2018, pp. 65–66)

- ^ De Waal (2018, p. 67)

- ^ De Waal (2018, p. 68)

- ^ a b c Blondeau (2023, p. 6)

- ^ a b Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, p. 276)

- ^ a b Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, p. 275)

- ^ a b Leblanc (2019, pp. 15, 57)

- ^ a b c Budiansky (1997, p. 148)

- ^ Leblanc (2019, p. 19)

- ^ a b Franchini (2009, p. 77)

- ^ Lansade (2023, pp. 141–142)

- ^ a b Leblanc (2019, p. 15)

- ^ a b Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, p. 274)

- ^ Franchini (2009, p. 65)

- ^ Franchini (2009, p. 19)

- ^ Franchini (2009, pp. 16–17)

- ^ Leblanc (2019, p. 11)

- ^ a b c Budiansky (1997, pp. 150–151)

- ^ Franchini (2009, pp. 193–194)

- ^ a b c Franchini (2009, p. 10)

- ^ Franchini (2009, p. 14)

- ^ Franchini (2009, pp. 15–16)

- ^ a b Budiansky (1997, p. 162)

- ^ Budiansky (1997, pp. 162–163)

- ^ Dempsey, P. J.; Montague, Sarah (2003). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Horses: The Inside Track on the Care and Grooming of the Most Common Breeds. Penguin. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-4406-9584-1.

- ^ Schofler, Patti (2006). Flight without Wings: The Arabian Horse And The Show World. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 304. ISBN 978-1-4617-4892-2.

- ^ Leblanc (2022, p. 51)

- ^ a b c Vidament, Marianne; Lansade, Léa. "Compréhension par les chevaux de certains états mentaux des humains" [Horses' understanding of certain human mental states]. equipedia.ifce.fr (in French). Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ^ Lansade (2023, p. 167)

- ^ a b Vidament, Marianne; Lansade, Léa; Jardat, Plotine (2022). "Attribution d'une réputation aux humains et contagion émotionnelle entre chevaux" [Reputation attribution to humans and emotional contagion among horses]. equipedia.ifce.fr (in French). Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ^ a b Franchini (2009, pp. 50–51)

- ^ a b Leblanc (2019, p. 65)

- ^ a b Lansade (2023, pp. 181–183)

- ^ a b Leblanc (2019, p. 64)

- ^ a b Leblanc (2019, p. 52)

- ^ Leblanc (2019, pp. 53–55)

- ^ Blake, Henry (2011). Talking with Horses. Souvenir Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-285-63945-4.

- ^ Kidd, Ian James; McKinnell, Liz (2015). Science and the Self: Animals, Evolution, and Ethics: Essays in Honour of Mary Midgley. Routledge. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-317-48293-2.

- ^ Despret (2015, pp. 35, 41–44)

- ^ a b c Budiansky (1997, p. 153)

- ^ a b c d Budiansky (1997, p. 151)

- ^ a b c Leblanc (2019, p. 59)

- ^ Franchini (2009, pp. 84–85)

- ^ Franchini (2009, pp. 128–129)

- ^ Lansade (2023, p. 184)

- ^ Franchini (2009, pp. 32–33)

- ^ Leblanc (2019, pp. 53–54)

- ^ a b Leblanc (2019, p. 55)

- ^ Lansade (2023, p. 170)

- ^ Lansade (2023, p. 142)

- ^ Franchini (2009, pp. 117–118)

- ^ Franchini (2009, p. 137)

- ^ a b c d e f g Vidament, Marianne; Lansade, Léa; Jardat, Plotine (2021). "Reconnaissance des êtres humains par les chevaux" [Recognition of Human Beings by Horses]. equipedia.ifce.fr (in French). Retrieved September 4, 2023.

- ^ Lansade (2023, pp. 143–148)

- ^ a b Lansade (2023, p. 148)

- ^ Lansade, Léa (2023a). "Les chevaux nous reconnaissent-ils?" [Do horses recognize us?]. The Conversation (in French). Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ^ Lansade (2023, pp. 168–169)

- ^ Lansade (2023, pp. 149–150)

- ^ Lansade (2023, pp. 150–151)

- ^ Lansade (2023, pp. 152–153)

- ^ Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, p. 272)

- ^ Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, p. 273)

- ^ Lansade (2023, pp. 25–29)

- ^ Antoine, Guillaume; Soulage, Laure; Wattinne, Stéphane (2020). Le cheval coach - L'équicoaching: une expérience transformante [Le cheval coach - Equicoaching: a transforming experience] (in French). Yves Michel. p. 31. ISBN 978-2-36429-158-4.

- ^ a b Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, p. 298)

- ^ Franchini (2009, pp. 80–82)

- ^ a b c Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, p. 284)

- ^ Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, p. 283)

- ^ Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, p. 291)

- ^ a b c d Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, p. 290)

- ^ a b c Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, p. 296)

- ^ Lansade (2023, p. 185)

- ^ Lansade (2023, p. 186)

- ^ Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, p. 288)

- ^ Lansade (2023, p. 193)

- ^ Lansade (2023, pp. 187–188)

- ^ Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, p. 297)

- ^ a b Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, p. 295)

- ^ Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, pp. 296–297)

- ^ Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, pp. 290, 293)

- ^ a b c Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, p. 277)

- ^ Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, pp. 277–278)

- ^ a b c Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, p. 278)

- ^ Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, p. 280)

- ^ Leblanc & Bouissou (2021, pp. 280–281)

- ^ Franchini (2009, p. 95)

- ^ Kohanov, Linda (2019). Pour un leadership socialement intelligent [For socially intelligent leadership] (in French). Courrier du livre. p. 170. ISBN 978-2-7029-1716-9.

- ^ Franchini (2009, p. 9)

- ^ Glanowski, Émilie (2015). "Bucéphale, compagnon d'exception d'Alexandre: la construction d'un mythe" [Bucephalus, Alexander's exceptional companion: the construction of a myth]. Circé. Histoire, Savoirs, Sociétés (in French). Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Boratav, Pertev (1965). Aventures merveilleuses sous terre et ailleurs de Er-Töshtük le géant des steppes [Er-Töshtük the steppe giant's wonderful adventures underground and elsewhere] (in French). Paris: Gallimard/Unesco. p. 312. ISBN 2-07-071647-3.

- ^ Chevalier, Jean; Gheerbrant, Alain (1982). Dictionnaire des symboles [Dictionary of symbols] (in French). Seghers. p. 223. ISBN 9782221502112.

- ^ Kersalé, Patrick; Saye, Zakari (2001). Mali: parole d'ancêtre dogon: l'écho de la falaise [Mali: Dogon ancestor's word: the echo of the cliff] (in French). Anako. p. 172. ISBN 978-2-907754-69-9.

- ^ Gbado, Béatrice Lalinon; Chevaux fabuleux; Cotonou; Ruisseaux d'Afrique (2011). "Le Destin" [Destiny]. Sagesses africaines [African wisdom] (in French). p. 76. ISBN 978-99919-63-66-2.

- ^ Hodne, Ørnulf (1984). The Types of the Norwegian Folktale. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. pp. 123–125. ISBN 9788200068495.

- ^ Pitrè, Giuseppe (2009). The Collected Sicilian Folk and Fairy Tales of Giuseppe Pitrè. London: Routledge. p. 973. ISBN 978-0-415-98031-9.

- ^ Duggan, Anne E.; Haase, Donald; Callow, Helen J. (2016). Folktales and Fairy Tales: Traditions and Texts from around the World. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 567. ISBN 978-1-61069-254-0.

- ^ a b Wagner, Marc-André (2005). Le cheval dans les croyances germaniques: paganisme, christianisme et traditions [The horse in Germanic beliefs: paganism, Christianity and traditions] (in French). Champion. pp. 543–545. ISBN 978-2-7453-1216-7.

- ^ Ferry, Ilan (2022). La Mythologie selon Le Seigneur des Anneaux [Mythology according to The Lord of the Rings] (in French). Les Éditions de l'Opportun. p. 97. ISBN 978-2-38015-258-6.

- ^ Farley, Walter (2021). L'Étalon Noir. Hachette Jeunesse. p. 131. ISBN 978-2-01-714528-8.

- ^ Delylle, Antoinette; Muller, Cathy (2014). L'Encyclo de la cavalière [Rider's Encyclopaedia] (in French). edi8. p. 133. ISBN 978-2-324-00849-8.

Academic references

- ^ a b c Brubaker & Udell (2016, p. 121)

- ^ Barreau & Porcher (2023, p. 33)

- ^ a b c d e f g Hanggi (2005, p. 246)

- ^ Deneux-le Barh (2023, pp. 13–14)

- ^ a b Deneux-le Barh (2023, p. 14)

- ^ Barreau & Porcher (2023, p. 34)

- ^ a b Barreau & Porcher (2023, p. 36)

- ^ Deneux-le Barh (2023, p. 17)

- ^ a b c d Barreau & Porcher (2023, p. 37)

- ^ a b Deneux-le Barh (2023, p. 18)

- ^ a b c Deneux-le Barh (2023, p. 19)

- ^ a b Dubost (2014, p. 190)

- ^ Deneux-le Barh (2023, p. 20)

- ^ Gray, Floyd (2008). "Chapitre 2. Le langage des animaux" [Chapter 2. Animal language]. La renaissance des mots. De Jean Lemaire de Belges à Agrippa d'Aubigné [The renaissance of words. From Jean Lemaire de Belges to Agrippa d'Aubigné] (in French). Classiques Garnier. ISBN 978-2-37312-205-3.

- ^ Deneux-le Barh (2023, p. 21)

- ^ Deneux-le Barh (2023, p. 22)

- ^ a b c Deneux-le Barh (2023, p. 23)

- ^ a b c d e Porcher (2023, p. 9)

- ^ Hamm, Elisabeth (2019). "Le cheval astronomique à la croisée des savoirs: une lecture des scènes de foire dans Woyzeck de Georg Büchner" [The astronomical horse at the crossroads of knowledge: a reading of the fairground scenes in Georg Büchner's Woyzeck]. Revue d'Allemagne et des pays de langue allemande (in French). 51 (2): 357–370. doi:10.4000/allemagne.1981. ISSN 0035-0974. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ^ Dray (2023, p. 77)

- ^ a b c Deneux-le Barh (2023, p. 24)

- ^ a b c Leblanc (2022, p. 57)

- ^ a b c Dray (2023, p. 74)

- ^ a b c d Dray (2023, p. 80)

- ^ Dray (2023, p. 81)

- ^ Leblanc (2022, p. 68)

- ^ a b Brubaker & Udell (2016, pp. 121–122)

- ^ Stollznow, Karen (2014). "Pet Psychics and Psychic Pets". Language Myths, Mysteries and Magic. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 179–192. doi:10.1057/9781137404862_18. ISBN 978-1-137-40486-2.

- ^ a b Leblanc (2022, p. 69)

- ^ Deneux-le Barh (2023, p. 25)

- ^ a b Leblanc (2022, p. 77)

- ^ McCall, Cynthia A. (2007). "Making equine learning research applicable to training procedures". Behavioural Processes. 76 (1): 27–8, discussion 57–60. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2006.12.008. ISSN 0376-6357. PMID 17433568. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ a b Leblanc (2022, p. 86)

- ^ Leblanc (2022, pp. 13, 25)

- ^ a b c Leblanc (2022, p. 13)

- ^ a b c Porcher (2023, p. 10)

- ^ Álvares (2023, pp. 53–54)

- ^ a b c d e f Brubaker & Udell (2016, p. 122)

- ^ Porcher (2023, pp. 10–11)

- ^ a b c Barreau & Porcher (2023, p. 35)

- ^ Leblanc (2022, p. 71)

- ^ Leblanc (2022, p. 73)

- ^ Leblanc (2022, p. 75)

- ^ Barreau & Porcher (2023, p. 41)

- ^ a b Barreau & Porcher (2023, p. 39)

- ^ Deneux-le Barh (2023, p. 27)

- ^ Deneux-le Barh (2023, p. 1)

- ^ Deneux-le Barh (2023, p. 12)

- ^ Deneux-le Barh (2023, p. 13)

- ^ Deneux-le Barh (2023, pp. 12–13)

- ^ Barreau & Porcher (2023, pp. 50–51)

- ^ a b Deneux–Le Barh (2023, p. 13)

- ^ a b Dray (2023, p. 79)

- ^ a b c Leblanc (2022, p. 326)

- ^ Leblanc (2022, pp. 93–94)

- ^ a b Álvares (2023, p. 55)

- ^ a b Leblanc (2022, p. 59)

- ^ Álvares (2023, p. 54)

- ^ a b Lesimple, Clémence; Sankey, Carol; Richard, Marie-Annick; Hausberger, Martine (2012). "Do Horses Expect Humans to Solve Their Problems?". Frontiers in Psychology. 3: 306. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00306. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 3426792. PMID 22936923.

- ^ Hausberger, M.; Stomp, M.; Sankey, C.; Brajon, S. (2019). "Mutual interactions between cognition and welfare: The horse as an animal model". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 107: 540–559. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.08.022. ISSN 0149-7634. PMID 31491471. Retrieved September 3, 2023.

- ^ a b Krueger, Konstanze; Flauger, Birgit (2007). "Social learning in horses from a novel perspective" (PDF). Behavioural Processes. 76 (1): 37–39. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2006.08.010. ISSN 0376-6357. PMID 17428621.

- ^ Leblanc (2022, pp. 72, 86)

- ^ a b c Lindberg, A. C.; Kelland, A.; Nicol, C. J. (1999). "Effects of observational learning on acquisition of an operant response in horses". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 61 (3): 187–199. doi:10.1016/S0168-1591(98)00184-1. ISSN 0168-1591. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ a b c Krueger, Konstanze; Farmer, Kate; Heinze, Jürgen (2014). "The effects of age, rank and neophobia on social learning in horses". Animal Cognition. 17 (3): 645–655. doi:10.1007/s10071-013-0696-x. ISSN 1435-9456. PMID 24170136. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ Leblanc (2022, p. 29)

- ^ Leblanc (2022, p. 35)

- ^ Leblanc (2022, p. 46)