Chandelier

A chandelier (/ˌʃændəˈlɪər/) is an ornamental lighting device, typically with spreading branched supports for multiple lights, designed to be hung from the ceiling.[1][2] Chandeliers are often ornate, and they were originally designed to hold candles, but now incandescent light bulbs are commonly used,[3] as well as fluorescent lamps and LEDs.

A wide variety of materials ranging from wood and earthenware to silver and gold can be used to make chandeliers. Brass is one of the most popular with Dutch or Flemish brass chandeliers being the best-known, but glass is the material most commonly associated with chandeliers. True glass chandeliers were first developed in Italy, England, France, and Bohemia in the 18th century. Classic glass and crystal chandeliers have arrays of hanging "crystal" prisms to illuminate a room with refracted light. Contemporary chandeliers may assume a more minimalist design, and they may illuminate a room with direct light from the lamps or are equipped with translucent glass shades covering each lamp. Chandeliers produced nowadays can assume a wide variety of styles that span modernized and traditional designs or a combination of both.

Although chandeliers have been called candelabras, chandeliers can be distinguished from candelabras which are designed to stand on tables or the floor, while chandeliers are hung from the ceiling. They are also distinct from pendant lights, as they usually consist of multiple lamps and hang in branched frames, whereas pendant lights hang from a single cord and only contain one or two lamps with few decorative elements. Due to their size, they are often installed in large hallways and staircases, living rooms, lounges, and dining rooms, often as focus of the room. Small chandeliers can be installed in smaller spaces such as bedrooms or small living spaces, while large chandeliers are typically installed in the grand rooms of buildings such as halls and lobbies, or in religious buildings such as churches, synagogues or mosques.

Etymology

The word chandelier was first known in the English language in the sense as used today in 1736, borrowed from the word in French that means a candleholder. It may have been derived from chandelle meaning "tallow candle",[4] or chandelabre in Old French and candēlābrum in Latin, and ultimately from candēla meaning "candle".[5][6] In the earlier periods, the term "candlestick", chandelier in France, may be used to refer to a candelabra, a hanging branched light, or a wall light or sconce. In English, "hanging candlesticks" or "branches" were used to mean lighting devices hanging from the ceiling until chandelier began to be used in the 18th century.[7]

In France, chandelier still means a candleholder, and what is called chandelier in English is lustre in French, a term first used in the late-17th century.[8] The French lustre, from Italian lustro, can also be used in English to mean a chandelier hung with crystals, or the glass pendant used to decorate such chandelier.[9] The use of words for indoor lighting devises can be confusing, and a number of terms like lustres, branches, chandeliers and candelabras were used interchangeably at various times, which can make the early appearance of these words misleading.[4] Girandole was also once used to refer to all candelabra as well as chandelier,[7] although girandole now usually means an ornate branched candleholder that may be mounted on a wall, often with a mirror.[10] Chandeliers may sometimes be called suspended lights, although not all suspended lights are necessarily chandeliers.

History

Precursors

Hanging lighting devices, some described as chandeliers, were known since ancient times, and circular ceramic lamps with multiple points for wicks or candles were used in the Roman period.[11][12] The Roman terms lychnuchus or lychnus, however, can refer to candlestick, floor lamps, candelabra, or chandelier.[13] By the 4th century, terms such as coronae, phari, pharicanthari were used, and they were often mentioned as presents of the popes.[14]

In the Byzantine period, flat circular metallic structures suspended with chains that can hold oil lamps known as polycandela (singular polycandelon) were commonly used throughout the eastern Mediterranean.[15][16] First developed in late antiquity, polycandela were used in churches and synagogues, and took the shape of a bronze or iron frame holding a varying number of globular or conical glass beakers provided with a wick and filled with oil.[15][17] They may be hung between columns, over the altar or tombs of saints.[18] Polycandela were also commonly used to furnish households up until the 8th century.[19]

Hanging lamps were commonly found in mosques in Islamic countries, while sanctuary lamps were found in churches. In Spain which had significant Moorish influence, hanging farol lanterns made of pierced brass and bronze as well as glass were produced. A type of Spanish silver lampadario with an elongated central reservoir for oil may have developed into a form of chandelier that has a central baluster and branching arms.[20]

The early form of hanging lighting devices in religious buildings may be of considerable size. Huge hanging lamps in Hagia Sophia were described by Paul the Silentiary in 563:[21] "And beneath each chain he has caused to be fitted silver discs, hanging circle-wise in the air, round the space in the center of the church. Thus these discs, pendant from their lofty courses, form a coronet above the heads of men. They have been pierced too by the weapon of the skillful workman, in order that they may receive shafts of fire-wrought glass and hold light on high for men at night."[22] In the late 8th century, Pope Adrian I was said to have presented the St. Peter's Basilica with a chandelier that could hold 1,370 candles, while his successor Pope Leo III presented a golden corona decorated with jewels to the Basilica of St. Andrew.[14] The Venerable Bede mentioned that it was customary to have two hanging lighting devices called phari in a major English church, one in the nave and one in the choir, which may be a large bronze hoop with lamps hung over the figure of a cross.[23]

Early chandeliers

In the medieval period, circular crown-shaped hanging devices made of iron called the corona (couronne de lumière in France and corona de luz in Spain) were used in many European countries in religious buildings since the 9th century.[24] The larger Romanesque or Gothic-style circular wheel chandeliers were also recorded in Germany, France, and the Netherlands in the 11th and 12th century. Four Romanesque wheel chandeliers survive in Germany, including to be the Azelin and Hezilo chandeliers in Hildesheim Cathedral, and the Barbarossa Chandelier in the Aachen Cathedral.[25] These large structures may be considered the first true chandeliers.[26] These chandeliers have prickets (vertical spikes for holding candles) and cups for oil and wicks. A hammered iron corona with floral decorated was recorded in the St Paul's Cathedral in London in the 13th century.[27] The iron chandeliers may have polychrome paint as well as jewel and enamelwork decorations.[27]

Wooden cross-beam chandeliers were the early form of chandelier used in a domestic setting and they were found in the households of the wealthy in the medieval period. The wooden cross beams were attached to a vertical wooden pillar, and on each of the four arms a candle may be placed. Some that could hold two candles in each arm were called "double candlesticks".[27] While simple in design compared to later chandeliers, such wooden chandeliers were still found in the court of Charles VI of France in the 15th century and a double candlestick was listed in the inventory of the estate of Henry VIII of England in the 16th century.[27] In the medieval period, chandeliers may also be lighting devices that could be moved to different rooms.[28] In later periods, wood used in chandeliers may be carved and gilded.[7]

By the late Gothic period, more complex forms of chandeliers appeared. Chandeliers with many branches radiating out from a central stem, sometimes in tiers, were made by the 15th century, and these may be adorned with statuettes and foliated decorations.[29] Chandelier became popular decorative features in palaces and homes of nobility, clergy and merchants, and their high cost made chandeliers symbols of luxury and status. A diverse range of materials were also employed in the making of chandeliers. In Germany, a form of chandeliers made of deer antlers and wooden sculpted figures called lusterweibchen were known to have been made since the 14th century.[30] Ivory chandeliers in the palace of the king of Mutapa, were depicted in a 17th-century description by Olfert Dapper.[31] Porcelain introduced to Europe were also used to make chandeliers in the 18th century.[32]

Brass chandelier

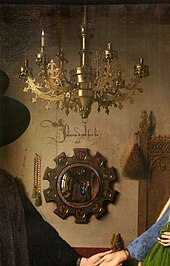

Many different metallic materials have been used to make chandeliers, including iron, pewter, bronze, or more prestigiously silver and even gold. Brass, however, has the warm appearance of gold while being considerably cheaper, and also easy to work with, it therefore became a popular choice for making chandeliers.[33] Brass or brass-like latten has been used to make chandeliers since the medieval period, and many were made with brass-type alloy from Dinant (now in Belgium, brass ware from the town was known as dinanderie) until the mid-15th century.[34] The metal chandeliers may have a central support with curved or S-shaped arms attached, and at the end of each arm is a drip-pan and nozzle for holding a candle; by the 15th century, candle nozzles were used instead of prickets to hold the candles since candle production techniques allowed for the production of identically sized candles.[34] Many such brass chandeliers can be seen depicted in Dutch and Flemish paintings from the 15th to 17th centuries.[35] These Dutch and Flemish chandeliers may be decorated with stylized floral embellishments as well as Gothic symbols and emblems and religious figures.[36] Large numbers of brass chandeliers existed, but most of the early brass chandeliers did not survive destruction during the Reformation.[37]

The Dutch brass chandeliers have distinctive features – a large brass sphere at the end of a central ball stem, and six curved low-swooping arms. The globe helps to keep the chandelier upright and reflect the light from candles, and the arms are curved downward to bring the candles to the level of the sphere to allow for maximum reflection.[38] The arms of early brass chandeliers may also have drooped lower through use over time as the brass used in the earlier period was softer due to lower zinc content.[39] Many Dutch chandeliers were topped by a double-headed eagle by the 16th century.[40] The features of Dutch brass chandeliers were widely copied in other countries, and this form is arguably the most successful and long-lasting of all types of chandeliers.[41] Dutch brass chandeliers were popular across Europe, particularly in England, as well as in the United States. Variations of the Dutch brass chandelier were produced, for example there may be multiple tiers of the arms, the sphere may become elongated, or the arms may emerge from the globe itself.[42] By the early 18th century, ornate cast ormolu forms with long, curved arms and many candles were in the homes of many in the growing merchant class.

Glass and crystal chandeliers

Chandeliers began to be decorated with carved rock crystal (quartz) of Italian origin in the 16th century, a highly expensive material. The rock crystal pieces were hung from a metal frame as pendants or drops. The metal frame of French chandeliers may have a central stem onto which arms are attached, later some may form a cage or "birdcage" without a central stem. Few, however, could afford these rock crystal chandeliers as they were costly to produce. In the 17th century multi-faceted crystals that could reflect light from the candles were used to decorate chandelier and they were called chandeliers de crystal in France.[8] The chandeliers produced in France in the 17th century were in the French Baroque style, and rococo in the 18th century. French rock crystal chandeliers found their finest expression under Louis XIV, as exemplified by chandeliers at the Palace of Versailles.[43]

Rock crystal began to be replaced by cut glass in the late 17th century.[8] and examples of chandeliers made with rock crystal as well as Bohemian glass can be found in the Palace of Versailles.[44] Crystal chandeliers in the early period were literally made of crystals, but what are called crystal chandeliers now are almost always made of cut glass. Glass, although not crystalline in structure, continued to be called crystal, after much clearer cut glass that resembled crystal was produced from the late 17th-century. Quartz is nevertheless still more reflective than the best glass, and lead glass that is perfectly clear was not produced until 1816.[45] Although France is believed to have produced lead glass in the late-17th century, France used imported glass for its chandeliers until the late 18th century when high quality glass was produced in the country.[46]

The origin of the glass chandelier is unclear, but some scholars believed that the first glass chandelier was made in 1673 in Orléans France, where a simple iron rod was encased in multi-coloured glass with glass arms attached.[47] By the turn of the 18th century, glass chandeliers were produced in France, England, Bohemia, and Venice.[47] In Britain, Lead glass was developed by George Ravenscroft c. 1675, which allowed for the production of cheaper lead crystal that resembles rock crystal without the crisseling defects of other glass.[48] It is also relatively soft compared to soda glass, allowing it to be cut or faceted without shattering. Lead glass also rings when struck, unlike soda glass which has no resonance.[49] The clearness and light scattering properties of lead glass made it a popular addition to the form, and conventionally, lead glass may be the only glass that can be described as crystal. The first mention of a glass chandelier in an advertisement appeared in 1727 (as schandelier) in London.[4]

The design of the first English true glass chandelier was influenced by Dutch and Flemish brass chandeliers.[4] These English chandeliers were made largely of glass, with the metal parts limited to the central stem and receiver plates and bowls. The metallic part may be silvered or silver-plated, and the silver-plating inside the glass stem can create the illusion that the chandelier is made entirely of glass.[51] A glass bowl at the bottom disguises the metal disc onto which the glass arms are attached.[4] The early glass chandeliers were molded and uncut, often with solid rope-twist arms. Later cuts to the arms were introduced to provide sparkle, and additional ornaments added. Cut glass pendant drops were hung from the frame, initially only a small number, but in increasingly large number by c.1770.[52] By the 1800s, the decorative ornaments became so abundant that the underlying structure of the chandelier became obscured.[52] The early chandeliers may follow a rococo style, and later neo-classical style, A notable early producer of glass chandeliers was William Parker; Parker replaced the Dutch-influenced ball stem with a vase-shaped stem, as seen in the chandeliers in Bath Assembly Rooms, which were the first datable neo-Classical style chandeliers as well as the first chandeliers that were signed by the maker.[53] Other designers of neo-Classical chandeliers were Robert and James Adam.[52] Neoclassical motifs in cast metal or carved and gilded wood were common elements in these chandeliers. Chandeliers made in this style also drew heavily on the aesthetic of ancient Greece and Rome, incorporating clean lines, classical proportions and mythological creatures.[46]

Bohemia in present-day Czech Republic has been producing glass for centuries. Bohemian glass contains potash that gives it a clear colorless appearance, which became renown in Europe in the 18th century. Production of crystal chandeliers appeared in Bohemia and Germany in the early 18th century, with designs that followed what were popular in England and France,[54] and many early chandeliers were copies of designs from London.[8] Bohemia soon developed its own styles of chandeliers, the best-known of which is the Maria-Theresa, named after the Empress of Austria. This type of chandeliers do not have a central baluster, and their distinctive feature is the curved flat metal arms placed between sections of molded glass joined together with glass rosettes.[55] Some Bohemian chandeliers used wood instead of metal as the central stem due to the abundance of wood and wood carvers in the area.[54] The Bohemian style was largely successful across Europe and its biggest draw was the chance to obtain spectacular light refraction due to the facets and bevels of crystal prisms. Glass chandeliers became the dominant form of chandelier from about 1750 until at least 1900, and the Czech Republic remains a great producer of glass chandeliers today.[8]

Venice has been a center of glass production, particularly on the island of Murano. The Venetians created a form of soda–lime glass by adding manganese dioxide that is clear like crystal, which they called cristallo.[56] This glass was typically used to make mirrors, but around 1700, Italian glass factories in Murano started creating new kinds of artistic chandeliers. Since Murano glass is hard and brittle, it is not suitable for cutting/faceting; however, it is lighter, softer and more malleable when heated, and Venetian glassmakers relied upon the properties of their glass to create elaborate forms of chandelier.[49] Typical features of a Murano chandelier are the intricate arabesques of leaves, flowers and fruits that would be enriched by colored glass, made possible by the specific type of glass used in Murano.[56] Great skill and time was required to twist and shape a chandelier precisely.

The ornate type of murano chandelier is called ciocca (literally "bouquet of flowers") for the characteristic decorations of glazed polychrome flowers. The most sumptuous consisted of a metal frame covered with small elements in blown glass, transparent or colored, with decorations of flowers, fruits and leaves, while simpler models had arms made with unique pieces of glass. Their shape was inspired by an original architectural concept: the space on the inside is left almost empty, since decorations are spread all around the central support, distanced from it by the length of the arms. Huge Murano chandeliers were often used for interior lighting in theaters and rooms in important palaces.[57] Despite periods of decline and revival, designs of Murano glass chandeliers have stayed relatively constant through time, and modern productions of these chandelier may still be stylistically nearly identical to those made in the 18th or 19th centuries.[56] Glass arms that were hollow were produced instead of solid glass to accommodate gas lines or electrical wiring were produced by the late 19th century.[47]

Chandeliers were also produced in other countries in the 18th century, including Russia and Sweden. Russian and Scandinavian chandeliers are similar in designs, with a metal frame that is lighter and more decorative, gilded or finished with brass, and hung with small slender glass drops.[8] Russian chandeliers may be accented with coloured glass.[58]

19th century

The 19th century was a period of great changes and development; the industrial revolution and the growth of wealth from the industries greatly increased the market for chandeliers, new methods of lighting and better techniques of production emerged. Other countries such as the United States also started producing chandeliers; the first American chandelier is believed to date from 1804.[59] New styles and more complex and elaborate chandeliers also appeared, and production of chandeliers reached a peak in the 19th century. France, which only started producing significant amount of high-quality glass in the late 18th century, became renown as a producer of the finest quality chandeliers. One of the best-known French manufacturers, Baccarat, started making chandeliers in 1824. In England, Perry & Co. produced a large quantity of chandeliers, while F. & C. Osler was known for producing spectacular chandeliers, the great proportion of which went to India, the richest market for chandeliers at that time.[8] In 1843, Osler opened a branch in Calcutta to start production of chandeliers in India.[60]

In England, the imposition of the Glass Excise Act on all glass products in 1811 led to a new style of chandelier being created. Chandelier makers, in order to avoid paying the tax, reused broken glass pieces cut into crystal icicles and strung together, and hung from circular frames in the form of tent or canopy above a hoop, with a bag below and/or tiered sheets that resembled waterfalls. A large number of crystals are used to make such chandeliers, and many may contain over 1,000 pieces of crystal. The central stem is hidden by the crystals. These forms of Regency-era chandeliers were popular all over Europe.[52] In France, chandeliers of similar designs are described as Empire style. After the Glass Excise Act was repealed, chandeliers with glass arms became popular again, but they became larger, bolder and heavily decorated.[52] The largest English-made chandelier in the world (by Hancock Rixon & Dunt and probably F. & C. Osler) is in the Dolmabahçe Palace in Istanbul, and it has 750 lamps and weighs 4.5 tons.[61]

In the 19th century, a variety of new methods for producing light that are brighter, cleaner or more convenient than candles began to be used. These included colza oil (Argand lamp), kerosene/paraffin, and gas.[63] Due to its brightness, gas was initially only used for public lighting, later it also appeared in homes.[64] As gas lighting caught on, branched ceiling fixtures called gasoliers (a portmanteau of gas and chandelier) were produced. Many candle chandeliers were converted. Gasoliers may have only slight variations in the decorations from chandeliers, but the arms were hollow to carry the gas to the burners.[8] Examples of gasoliers were the extravagant chandeliers in the Royal Pavilion in Brighton first installed in 1821.[62] While popular, gas lighting was considered too bright and harsh on the eyes, and lacking the pleasing quality of candlelight.[65] Shades that surround the gas light were then added to reduce the glare. Gas lighting was eventually replaced by electric light bulbs in the early 20th century.[66]

Electric lighting began to be introduced widely in the late 19th century. For a time, some chandeliers used both gas and electricity, with gas nozzles pointing upward while the light bulbs hung downward.[67] As distribution of electricity widened, and supplies became dependable, electric-only chandeliers became standard. Another portmanteau word, electrolier, was coined for these, but nowadays they are most commonly still called chandeliers even though no candles are used. Glass chandeliers requires electrical wiring, large areas of metals and light bulbs, but the results were often not aesthetically pleasing.[8] A large number of light bulbs close together can also produce too much glare.[68] Shades for the bulbs of these electroliers were therefore often added.

Modern chandeliers

At the turn of the 20th century, the chandelier still enjoyed the status it had the previous century. Of the many lighting fixtures made that conformed to the popular contemporary styles of Art Nouveau, Art Deco and Modernism, few could be described properly as chandeliers.[69] The popularity of chandeliers declined in the 20th century. A vast array of lighting choices became available, and chandeliers often did not fit the aesthetics of modern architecture and interior design. Light fittings of avant-garde form and material however started to be made c. 1940.[69] A wide variety of chandeliers of modern design appeared, ranging from the minimalist to the highly extravagant. Towards the end of the 20th century, the popularity of chandeliers revived. A number of glass artists such as Dale Chihuly who produced chandeliers emerged. Chandeliers were often used as decorative focal points for rooms, although some do not necessarily illuminate.

Older styles of chandeliers continued to be produced in the 20th and 21st centuries, and older styles of chandeliers may also be revived, such as the Art Deco-style of chandeliers.[70]

Incandescent light bulbs became the most common source of lighting for modern chandeliers in the 20th century, and a variety of electrical lights such as fluorescent light, halogen. LED lamp are also used. Many antique chandeliers not designed for electrical wiring have also been adapted for electricity. Modern chandeliers produced in older styles and antique chandeliers wired for electricity usually use imitation candles, where incandescent or LED light bulbs are shaped like candle flames. These light bulbs may be dimmable to adjust the brightness. Some may use bulbs containing a shimmering gas discharge that mimics candle flame.[71]

Chandeliers around the world

The biggest chandeliers in the world are now found in the Islamic countries. The chandelier in the prayer hall in the Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque in Muscat, Oman was the biggest when it was installed in 2001. It is 14 m (45 ft) high, has a diameter of 8 m (26 ft), and weighs over eight tonnes (8,000 kg). It is lit by over 1,122 halogen lamps and contains 600,000 pieces of crystal.[72][73] The biggest chandelier in the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque in Abu Dhabi, with a diameter of 10 m, height of 15.5 m, weight of nearly 12 tonnes and lit with 15,500 LED lights, became the world's largest chandelier when it was installed in 2007.[74] In 2010, a chandelier of modern design was built in the foyer of an office building in Doha, Qatar. This chandelier has a height of 5.8 m (19 ft), width of 12 m (41 ft), length of 38 m (126 ft), and weight of 39,683 pounds (18 tonnes). It has 165,000 LED lights and 2,300 optical crystals and it is considered the biggest interactive LED chandelier in the world.[75] In 2022, a chandelier 47.7 m (156 ft) in height, 29.2 m (96 ft) in length and 28.3 m (93 ft) in width and weighing 16 tonnes was unveiled at the Assima Mall in Kuwait.[76] In Egypt, the largest and heaviest chandelier in the world, weighing 24,300 kg (53,572 lb) with a diameter of 22 m (72.2 ft) in four levels made by Asfour Crystal, was installed in the Grand Mosque of the Islamic Cultural Center in Cairo.[77][78]

Glossary of terms

- Adam style

- A Neoclassical style, light, airy and elegant chandelier – usually English.

- Arm

- The light-bearing part of a chandelier also sometimes known as a branch.

- Arm plate

- The metal or wooden block placed on the stem, into which the arms slot.

- Bag

- A bag of crystal drops formed by strings hanging from a circular frame and looped back into the center underneath, associated especially with early American crystal and Regency style crystal chandeliers.

- Baluster

- A turned wood or molded stem forming the axis of a chandelier, with alternating narrow and bulbous parts of varying widths.

- Bead

- A glass drop with a hole drilled in it.

- Bobèche

- A dish fitted just below the candle nozzle, designed to catch drips of wax. Also known as a drip pan.

- Branch

- Another name for the light-bearing part of a chandelier, also known as an arm.

- Cage

- An arrangement where the central stem supporting arms and decorations is replaced by a metal structure leaving the center clear for candles and further embellishments. Also called a "bird cage".

- Candlebeam

- A cross made from two wooden beams with one or more cups and prickets at each end for securing candles.

- Candle nozzle

- The small cup into which the end of the candle is slotted.

- Canopy

- An inverted shallow dish at the top of a chandelier from which festoons of beads are often suspended, lending a flourish to the top of the fitting.

- Corona

- Another term for crown-style chandelier.

- Crown

- A circular chandelier reminiscent of a crown, usually of gilded metal or brass, and often with upstanding decorative elements.

- Crystal

- Essentially a traditional marketing term for lead glass with a chemical content that gives it special qualities of clarity, resonance and softness, making it especially suitable for use in cut glass. Some chandeliers, as at the Palace of Versailles are actually made of cut rock crystal (clear quartz), which cut glass essentially imitates.

- Drip pan

- The dish fitted just below the candle nozzle, designed to catch drips of wax. Also known as a bobèche.

- Drop

- A small piece of glass usually cut into one of many shapes and drilled at one end so that it can be hung from the chandelier as a pendant with a brass pin. A chain drop is drilled at both ends so that a series can be hung together to form a necklace or festoon.

- Dutch

- Also known as Flemish, a style of brass chandelier with a bulbous baluster and arms curving down around a low hung ball.

- Festoon

- An arrangement of glass drops or beads draped and hung across or down a glass chandelier, or sometimes a piece of solid glass shaped into a swag. Also known as a garland.

- Finial

- The final flourish at the very bottom of the stem. Some Venetian glass chandeliers have little finials hanging from glass rings on the arms.

- Hoop

- A circular metal support for arms, usually on a regency-styles or other chandelier with glass pieces. Also known as a ring.

- Montgolfière chandelier

- A chandelier with a rounded bottom, like an inverted hot air balloon, named after the Montgolfier brothers, the early French balloonists.[citation needed]

- Molded

- The process by which a pressed glass piece is shaped by being blown into a mold.

- Neoclassical style chandelier

- A glass chandelier featuring many delicate arms, spires and strings of ovals rhomboids or octagons.

- Panikadilo

- Gothic candelabrum chandelier hung from centers of Greek Orthodox cathedrals' domes.

- Prism

- A straight, many-sided drop.

- Regency style chandelier

- A larger chandelier with a multitude of drops. Above a hoop, rises strings of beads that diminish in size and attach at the top to form a canopy. A bag, with concentric rings of pointed glass, forms a waterfall beneath. The stem is usually completely hidden.

- Soda glass

- A type of glass used typically in Venetian glass chandeliers. Soda glass remains "plastic" for longer when heated, and can therefore be shaped into elegant curving leaves and flowers. Refracts light poorly and is normally fire polished.

- Spire

- A tall spike of glass, round in section or flat sided, to which arms and decorative elements may be attached, made from wood, metal or glass.

- Tent

- A tent-shaped structure on the upper part of a glass chandelier where necklaces of drops attach at the top to a canopy and at the bottom to a larger ring.

- Venetian

- A glass from the island of Murano, Venice but usually used to describe any chandelier in Venetian style.

- Waterfall or wedding cake

- Concentric rings of icicle drops suspended beneath the hoop or plate.

Source: [79]

Gallery

-

11th century depiction of a corona

-

The Art of Painting by Johannes Vermeer, with a Dutch brass chandelier depicted

-

Gothic chandelier from Dortmund, Germany

-

Chandelier in the Uspenski Cathedral in Helsinki

-

Chandelier made of Capiz shells in Las Piñas Church, Philippines

-

A mid-18th century Murano glass chandelier by Giuseppe Briati

-

Chandeliers in the Hôtel de la Marine in Paris

-

Chandelier made of porcelain in the Salottino di porcellana

-

Ivory chandelier, late 18th-century, possibly Indian

-

Baccarat Eternal Lights in Tokyo

-

A chandelier with Bohemian glass

-

Art Nouveau chandelier by Hector Guimard

-

Chandeliers in a large billiard hall

-

Amber chandelier in Rosenborg Castle, early 18th century

-

Chandelier made of human bones in Sedlec Ossuary

-

Chandelier in the Festetics Palace

-

Chandelier in the Grand Kremlin Palace

-

Chandelier of modern design

-

Chandelier in the Royal Palace of Madrid

-

A chandelier in Edinburgh

-

Chandelier with lampshades

-

Chandelier fitted with flame-shaped light bulbs

-

A modern chandelier in Zurich

-

Chandelier in Seyyed Mosque, Iran

-

Chandelier in the Dolmabahçe Palace in Istanbul

-

Chandelier by Gérard Jean Galle

-

A chandelier in one of the Durga Puja pandals in West Bengal, India

-

An advertisement for the Central Chandelier Company out of Toledo, Ohio in 1895

-

One of the largest chandeliers ever produced, for the Al Ameen Mosque in Muscat (Oman), shortly before delivery

See also

- Candelabra

- Ceiling rose

- Girandole

- Ljuskrona

- J. & L. Lobmeyr, the first company to make an electric chandelier

- Light fixture

- Sconce

- Wheel chandelier

References

- ^ "Chandelier". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 3 May 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ "Chandelier". Cambridge Dictionary.

- ^ "Chandeliers for Lower Ceilings". KRM Light. 6 January 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-11-02. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ^ a b c d e Davison & Newton 2008, p. 69.

- ^ "Chandelier - definition". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ^ "Chandelier". Collins Dictionary.

- ^ a b c Joanna Banham, ed. (1997). Encyclopedia of Interior Design. Taylor & Francis. pp. 225–226. ISBN 9781136787584.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Davison & Newton 2008, p. 71.

- ^ "Luster". Merriam-Webster.

- ^ "Girandole". Collins Dictionary.

- ^ "Lamp: 1st century B.C.–4th century A.D." Getty Museum Collection.

- ^ Devereux, Charlie (28 August 2021). "Repaired Roman chandelier shines again". The Times. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021.

- ^ Papadopoulos & Moyes 2021, p. 460.

- ^ a b Lubke 1873, p. 171.

- ^ a b Quertinmont, Arnaud (2012-12-01). "Une scénographie de la Chrétienté et de l'Islam" [A scenography of Christianity and Islam] (in French). Morlanwelz: Musée royal de Mariemont. Archived from the original on 2021-04-26. Retrieved 2021-04-26.

- ^ "Polycandelon for six oil lamps". University of Michigan.

- ^ Dawson, Timothy George. "Aspects of everyday life and material culture in the Roman state: Lighting". Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- ^ Weitzmann 1979, p. 623.

- ^ "1975.41.145: Polycandelon". Harvard Art Museum.

- ^ McCaffety 2006, pp. 32–37.

- ^ "Polycandelon with Crosses". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ "Wondrous Glass: Reflections on the World of Rome c. 50 B.C. - A.D. 650". University of Michigan.

- ^ Hudson 1912, p. 6–7.

- ^ McCaffety 2006, p. 40.

- ^ Baur 1996, pp. 20.

- ^ McCaffety 2006, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d Hilliard 2001, p. 24.

- ^ Ruth A Johnston (15 August 2011). All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World. ABC-CLIO. p. 450. ISBN 978-0-313-36463-1. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ^ Hudson 1912, p. 7–9.

- ^ Davidson, Benjamin; Biddle, Pippa (1 January 2024). "Object lesson: Lights from the Dark Ages: The Lüsterweibchen". The Magazine Antiques.

- ^ Gardner F. Williams (2011). The Diamond Mines of South Africa: Some Account of Their Rise and Development. Cambridge University Press. p. 56. ISBN 9781108026598. Archived from the original on 2022-02-07. Retrieved 2021-11-28.

- ^ McCaffety 2006, p. 79.

- ^ Hilliard 2001, p. 45.

- ^ a b Hilliard 2001, p. 27.

- ^ Hilliard 2001, p. 8.

- ^ Smith 1994.

- ^ Hilliard 2001, pp. 48.

- ^ Hilliard 2001, pp. 46–50.

- ^ Hilliard 2001, p. 50.

- ^ McCaffety 2006, p. 51.

- ^ Hilliard 2001, pp. 49.

- ^ Hilliard 2001, p. 51.

- ^ "Chandelier – A Brief History Through Time". 21 April 2020.

- ^ Georges D'Hoste, J. (2006). All Versailles. Bonechi. pp. 27, 39. ISBN 978-8847622944.

- ^ McCaffety 2006, pp. 56–58.

- ^ a b "A History of the Chandelier". 16 May 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-06-17. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ a b c McCaffety 2006, p. 68.

- ^ Hilliard 2001, pp. 92–96.

- ^ a b Hilliard 2001, p. 76.

- ^ "Chandelier". National Trust.

- ^ McCaffety 2006.

- ^ a b c d e Davison & Newton 2008, p. 70.

- ^ McCaffety 2006, p. 85.

- ^ a b McCaffety 2006, p. 74.

- ^ McCaffety 2006, p. 75.

- ^ a b c Hilliard 2001, p. 75.

- ^ "Albrici - Antique Store in Florence". Albrici. Archived from the original on 2017-06-01. Retrieved 2017-05-20.

- ^ "The History of the Chandelier". Lights Online.

- ^ Hilliard 2001, pp. 109–110.

- ^ McCaffety 2006, p. 117.

- ^ Başkanlığı, Turkey Büyük Millet Meclisi Milli Saraylar Daire (2009). Shedding Light on an Era: The Collection of Lighting Appliances in 19th Century Ottoman Palaces. National Palaces Department of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey. ISBN 9789756226537. Archived from the original on 2020-07-27. Retrieved 2017-05-20.

- ^ a b Hilliard 2001, p. 108.

- ^ Hilliard 2001, pp. 63, 110.

- ^ Hilliard 2001, p. 63.

- ^ Hilliard 2001, p. 132.

- ^ Hilliard 2001, p. 65.

- ^ Hilliard 2001, p. 64.

- ^ Hilliard 2001, pp. 127–130.

- ^ a b Hilliard 2001, p. 153.

- ^ Clarkson, Meghan (2 February 2024). "Revive the Roaring Twenties with an Art Deco Style Chandelier". Best Seller Gallery. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ "Lampen". www.decofeelings.nl (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 2019-08-15. Retrieved 2017-05-20.

- ^ "The Biggest Chandelier in the World". Classic Chandeliers.

- ^ Saleh Al-Shaibany (1 October 2022). "Iconic carpet, chandelier at the Grand Mosque is a big attraction for tourists". Times of Oman.

- ^ Gillett, Katy (19 February 2021). "Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque: How a special task force preserved Abu Dhabi landmark's chandeliers in 45 days". The National.

- ^ "Reflective Flow: World's Largest Chandelier Weighs 39,683 Pounds". Lightopia.

- ^ "Assima Mall Chandelier In Kuwait Entered Guinness World Records". Kuwait Local. 1 December 2022.

- ^ "New capital's lavish mosque angers Egyptians facing poverty". BBC. 4 April 2023.

- ^ "Masjid Misr". Behance.

- ^ Hilliard 2001, p. 199–201.

Sources

- Baur, Veronika (1996). Metal Candlesticks: History, Styles and Techniques. Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 9780764301568.

- Davison, Sandra; Newton, R.G. (2008). Conservation and Restoration of Glass. Taylor & Francis. pp. 69–72. ISBN 9781136415517.

- Hilliard, Elizebeth (2001). Chandeliers. Bulfinch Press, Little Brown. ISBN 978-0821227688.

- Katz, Cheryl and Jeffrey. Chandeliers Rockport Publishers: 2001. ISBN 978-1-56496-805-0.

- Hudson, Hy A. (1912). "The Christmas Lights at Manchester Cathedral". Transaction Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society.

- Lubke, Wilhelm (1873). Ecclesiastical Art in Germany.

- McCaffety, Kerri (2006). The Chandelier Through the Centuries. Savoy House. ISBN 978-0-9709336-5-2.

- Papadopoulos, Costas; Moyes, Holley (2021). The Oxford Handbook of Light in Archaeology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198788218.

- Smith, John P. (1994). The art of enlightenment : a history of glass chandelier manufacture and design. Mallett.

- Weitzmann, Kurt (1979). Age of Spirituality. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0870991790.

- Parissien, Steven. Regency Style. Phaidon: 1992. ISBN 0-7148-3454-8.