Barry Lyndon

| Barry Lyndon | |

|---|---|

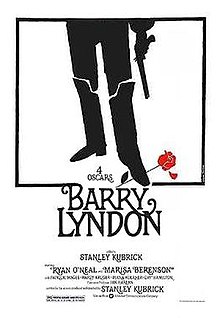

Theatrical release poster by Jouineau Bourduge | |

| Directed by | Stanley Kubrick |

| Screenplay by | Stanley Kubrick |

| Based on | The Luck of Barry Lyndon 1844 story in Fraser's Magazine by William Makepeace Thackeray |

| Produced by | Stanley Kubrick |

| Starring | |

| Narrated by | Michael Hordern |

| Cinematography | John Alcott |

| Edited by | Tony Lawson |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 185 minutes[1] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $11 million[2] |

| Box office | $31.5 million[2] |

Barry Lyndon is a 1975 epic historical black comedy-drama film written, directed, and produced by Stanley Kubrick, based on the 1844 novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon by William Makepeace Thackeray.[3] Narrated by Michael Hordern, and starring Ryan O'Neal, Marisa Berenson, Patrick Magee, Leonard Rossiter and Hardy Krüger, the film recounts the early exploits and later unravelling of an 18th-century Anglo-Irish rogue and gold digger who marries a rich widow to climb the social ladder and assume her late husband's aristocratic position.

Kubrick began production on Barry Lyndon after his 1971 film A Clockwork Orange. He had originally intended to direct a biopic on Napoleon, but lost his financing because of the commercial failure of the similar 1970 Dino De Laurentiis-produced Waterloo. Kubrick eventually directed Barry Lyndon, set partially during the Seven Years' War, utilising his research from the Napoleon project. Filming began in December 1973 and lasted roughly eight months, taking place in England, Ireland, and Germany.

The film's cinematography has been described as ground-breaking. Especially notable are the long double shots, usually ended with a slow backwards zoom, the scenes shot entirely in candlelight, and the settings based on William Hogarth paintings. The exteriors were filmed on location in England, Ireland, and Germany, with the interiors shot mainly in London.[4] The production had problems related to logistics, weather,[4] and politics (Kubrick feared that he might be an IRA hostage target).[5][6]

Barry Lyndon received seven nominations at the 48th Academy Awards, including Best Picture, winning 4: Best Original Score, Best Cinematography, Best Art Direction, and Best Costume Design. Although some critics took issue with the film's slow pace and restrained emotion, its reputation, like that of many of Kubrick's works, has grown over time. In the 2022 Sight & Sound Greatest Films of All Time poll, Barry Lyndon placed 12th in the directors' poll and 45th in the critics' poll.

Plot

Part I: "By What Means Redmond Barry Acquired the Style and Title of Barry Lyndon"

In the 1750s Kingdom of Ireland, Redmond Barry's father is killed in a duel. Barry becomes infatuated with his cousin Nora Brady, and shoots her suitor, British Army captain John Quin, in a duel. He flees but is robbed by highwaymen on his way to Dublin. Penniless, Barry enlists in the British Army. Family friend Captain Grogan informs him that Quin is not dead: the duel was staged so that Nora's family could get rid of Barry and improve their finances through her marriage to Quin.

Barry serves with his regiment in Germany during the Seven Years' War, but deserts after Grogan dies in combat against the French Royal Army. Absconding with a lieutenant's horse and uniform, Barry has a brief affair with Frau Lieschen, a married German peasant woman. On his way to Bremen, he encounters Captain Potzdorf, who sees through the ruse and impresses him into the Prussian Army. Barry later saves Potzdorf's life and receives a commendation from Frederick the Great.

At the end of the war, Barry is recruited by Captain Potzdorf's uncle into the Prussian Ministry of Police. The Prussians suspect that the Chevalier de Balibari, an Austrian diplomat and professional gambler, is in fact an Irishman and a spy for Empress Maria Theresa, and assign Barry to become his manservant. An emotional Barry confides everything to the Chevalier and they become confederates. After they win an enormous sum from the Prince of Tübingen at cards, the Prince deduces that he has been cheated and refuses to pay his debt; the Chevalier in turn threatens to demand satisfaction. To avoid a scandal, the Ministry of Police pays off the debt and quietly escorts the Chevalier outside Prussian borders, which allows Barry, disguised as the Chevalier, to leave the country as well.

Barry and the Chevalier travel across Europe, perpetrating similar gambling scams, with Barry forcing payment from debtors with sword duels. In Spa, he encounters the beautiful, wealthy, and visibly depressed Lady Lyndon. He seduces her, and goads her elderly husband Sir Charles Lyndon to death with verbal repartee.

Part II: "Containing an Account of the Misfortunes and Disasters Which Befell Barry Lyndon"

In 1773, Barry marries Lady Lyndon, takes her last name and settles in England. The Countess bears Barry a son, Bryan Patrick, whom Barry spoils. The marriage is unhappy: Barry is openly unfaithful and squanders his wife's wealth while keeping her in seclusion. Lord Bullingdon, Lady Lyndon's son by Sir Charles, still grieves for his father and sees Barry as a gold digger who does not love his mother. Barry responds with years of escalating emotional and physical abuse.

Barry's mother comes to live with him and warns him that if Lady Lyndon dies, Bullingdon will inherit everything. She advises her son to obtain a title. To this end, Barry cultivates the influential Lord Wendover and spends even larger sums of Lady Lyndon's money to ingratiate himself with high society. Bullingdon, now a young adult, interrupts a society party Barry throws. He publicly accuses his stepfather of infidelity, abuse and financial mismanagement, and announces that he will leave the Lyndon estate for as long as Barry remains there. Barry responds by brutally assaulting Bullingdon until they are physically separated by the party attendees. In the aftermath, Barry is ostracised by high society and plunges further into financial ruin.

Barry arranges to gift Bryan a full-grown horse for his ninth birthday. An impatient Bryan rides the horse unaccompanied and dies in a riding accident. Barry sinks into alcoholism, while Lady Lyndon seeks religious counseling from clergyman Samuel Runt, who had been tutor to Bullingdon and Bryan and a longtime companion of Lady Lyndon. When Barry's mother dismisses Runt to keep her son from losing control, Lady Lyndon attempts suicide. Runt and Graham, the family's steward, write to Bullingdon, who returns to the estate and challenges his stepfather to a duel.

After Bullingdon misfires the first shot, Barry fires into the ground in an effort to abort the duel. Bullingdon refuses to accept this as satisfaction and shoots Barry in the leg, forcing an amputation below the knee. While Barry is recovering, Bullingdon takes control of the Lyndon estate. Through Graham, he reminds Barry that his credit is exhausted and offers him 500 guineas a year to leave Lady Lyndon, her estates, and England forever. Barry grudgingly accepts and resumes his former gambling profession, but without any real success. In December 1789, a melancholic Lady Lyndon signs Barry's annuity cheque as her son looks on.

Cast

- Michael Hordern (voice) as Narrator

- Ryan O'Neal as Redmond Barry (later Redmond Barry Lyndon)

- Marisa Berenson as Lady Lyndon

- Patrick Magee as the Chevalier de Balibari

- Hardy Krüger as Captain Potzdorf

- Gay Hamilton as Nora Brady

- Godfrey Quigley as Captain Grogan

- Steven Berkoff as Lord Ludd

- Marie Kean as Belle, Barry's mother

- Murray Melvin as Reverend Samuel Runt

- Frank Middlemass as Sir Charles Reginald Lyndon

- Leon Vitali as Lord Bullingdon

- Dominic Savage as young Bullingdon

- Leonard Rossiter as Captain John Quin

- André Morell as Lord Wendover

- Anthony Sharp as Lord Hallam

- Philip Stone as Graham

- David Morley as Bryan Patrick Lyndon

- Diana Koerner as Lieschen (German Girl)

- Arthur O'Sullivan as Captain Feeney

- Billy Boyle as Seamus Feeney

- Jonathan Cecil as Lt. Jonathan Fakenham

- Peter Cellier as Sir Richard Brevis

- Geoffrey Chater as Dr Broughton

- Wolf Kahler as Prince of Tübingen

- Liam Redmond as Mr Brady

- Roger Booth as King George III

- Ferdy Mayne as Colonel Bulow

- John Sharp as Doohan

- Pat Roach as Corporal Toole

- Hans Meyer as Schulffen

Critic Tim Robey suggests that the film "makes you realise that the most undervalued aspect of Kubrick's genius could well be his way with actors."[7] He adds that the supporting cast is a "glittering procession of cameos, not from star names but from vital character players."[7]

The cast featured Leon Vitali as the older Lord Bullingdon, who then became Kubrick's personal assistant, working as the casting director on his following films, and supervising film-to-video transfers for Kubrick. Their relationship lasted until Kubrick's death. The film's cinematographer, John Alcott, appears at the men's club in the non-speaking role of the man asleep in a chair near the title character when Lord Bullingdon challenges Barry to a duel. Kubrick's daughter Vivian also appears (in an uncredited role) as a guest at Bryan's birthday party.

Other Kubrick featured regulars were Leonard Rossiter (2001: A Space Odyssey), Steven Berkoff, Patrick Magee, Godfrey Quigley, Anthony Sharp, and Philip Stone (A Clockwork Orange). Stone went on to feature in The Shining.

Thematic analysis

A main theme explored in Barry Lyndon is one of fate and destiny. Barry is pushed through life by a series of key events, some of which seem unavoidable. As Roger Ebert says, "He is a man to whom things happen."[8] He declines to eat with the highwayman Captain Feeney, where he would most likely have been robbed, but is robbed anyway farther down the road. The narrator repeatedly emphasizes the role of fate as he announces events before they unfold on screen, like Bryan's death and Bullingdon seeking satisfaction. This theme of fate is also developed in the recurring motif of the painting. Just like the events featured in the paintings, Barry is participating in events which always were.

Another major theme is between father and son. Barry lost his father at a young age and throughout the film he seeks and attaches himself to father-figures. Examples include his uncle, Grogan, and the Chevalier. When given the chance to be a father, Barry loves his son to the point of spoiling him. This contrasts with his role as a (step)father to Lord Bullingdon, whom he disregards and punishes.[8][9][10]

Production

Development

After completing post production on 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kubrick resumed planning a film about Napoleon. During pre-production, Sergei Bondarchuk and Dino De Laurentiis's Waterloo was released, and failed at the box office. Reconsidering, Kubrick's financiers pulled funding, and he turned his attention towards a film adaptation of Anthony Burgess's 1962 novel A Clockwork Orange. Subsequently, Kubrick showed an interest in Thackeray's Vanity Fair but dropped the project when a serialised version for television was produced. He told an interviewer, "At one time, Vanity Fair interested me as a possible film but, in the end, I decided the story could not be successfully compressed into the relatively short time-span of a feature film ... as soon as I read Barry Lyndon I became very excited about it."[11]

Having earned Oscar nominations for Dr. Strangelove, 2001: A Space Odyssey and A Clockwork Orange, Kubrick's reputation in the early 1970s was that of "a perfectionist auteur who loomed larger over his movies than any concept or star".[7] His studio—Warner Bros.—was therefore "eager to bankroll" his next project, which Kubrick kept "shrouded in secrecy" from the press partly due to the furore surrounding the controversially violent A Clockwork Orange (particularly in the UK) and partly due to his "long-standing paranoia about the tabloid press."[7] Kubrick was initially rumored to be developing an adaptation of Arthur Schnitzler's 1926 novella Dream Story, which would serve as the source material for his later film Eyes Wide Shut (1999).[12]

In 1972 Kubrick finally set his sights on Thackeray's 1844 "satirical picaresque about the fortune-hunting of an Irish rogue," The Luck of Barry Lyndon, the setting of which allowed Kubrick to take advantage of the copious period research he had done for the now-aborted Napoleon.[7][12] At the time, Kubrick merely announced that his next film would star Ryan O'Neal (deemed "a seemingly un-Kubricky choice of leading man"[7]) and Marisa Berenson, a former Vogue and Time magazine cover model,[13] and be shot largely in Ireland.[7] So heightened was the secrecy surrounding the film that "Even Berenson, when Kubrick first approached her, was told only that it was to be an 18th-century costume piece [and] she was instructed to keep out of the sun in the months before production, to achieve the period-specific pallor he required."[7]

Screenplay

Kubrick based his adapted screenplay on William Makepeace Thackeray's The Luck of Barry Lyndon (republished as the novel Memoirs of Barry Lyndon, Esq.), a picaresque tale written and published in serial form in 1844.

The film departs from the novel in several ways. In Thackeray's writings, events are related in the first person by Barry himself. A comic tone pervades the work, as Barry proves both a raconteur and an unreliable narrator. Kubrick's film, by contrast, presents the story objectively. Though the film contains voice-over (by actor Michael Hordern), the comments expressed are not Barry's, but those of an omniscient narrator. Kubrick felt that using a first-person narrative would not be useful in a film adaptation:[14]

I believe Thackeray used Redmond Barry to tell his own story in a deliberately distorted way because it made it more interesting. Instead of the omniscient author, Thackeray used the imperfect observer, or perhaps it would be more accurate to say the dishonest observer, thus allowing the reader to judge for himself, with little difficulty, the probable truth in Redmond Barry's view of his life. This technique worked extremely well in the novel but, of course, in a film you have objective reality in front of you all of the time, so the effect of Thackeray's first-person story-teller could not be repeated on the screen. It might have worked as comedy by the juxtaposition of Barry's version of the truth with the reality on the screen, but I don't think that Barry Lyndon should have been done as a comedy.

Kubrick made several changes to the plot, including the addition of the final duel.[15]

Principal photography

Principal photography lasted 300 days, from spring 1973 through to early 1974, with a break for Christmas.[16] Kubrick initially wished to film the entire production near his home in Borehamwood, but Ken Adam convinced him to relocate the shoot to Ireland.[12] The crew arrived in Dublin in May 1973. Jan Harlan recalls that Kubrick "loved his time in Ireland – he rented a lovely house west of Dublin, he loved the scenery and the culture and the people". [5]

Many of the exteriors were shot in Ireland, playing "itself, England, and Prussia during the Seven Years' War."[7] Kubrick and cinematographer Alcott drew inspiration from "the landscapes of Watteau and Gainsborough," and also relied on the art direction of Ken Adam and Roy Walker.[7] Alcott, Adam and Walker were among those who would win Oscars for their work on the film.[7][17]

Several of the interior scenes were filmed in Powerscourt House, an 18th-century mansion in County Wicklow. The house was destroyed in an accidental fire several months after filming (November 1974), so the film serves as a record of the lost interiors, particularly the "Saloon" which was used for more than one scene. The Wicklow Mountains are visible, for example, through the window of the saloon during a scene set in Berlin. Other locations included Kells Priory, County Kilkenny (the English Redcoat encampment);[18] Huntington Castle, County Carlow (exterior) and Dublin Castle, County Dublin (the chevalier's home). Some exterior shots were also filmed at Waterford Castle, County Waterford (now a luxury hotel and golf course) and Little Island, Waterford. Moorstown Castle in County Tipperary also featured. Several scenes were filmed at Castletown House in Celbridge, County Kildare; outside Carrick-on-Suir, County Tipperary, and at Youghal, County Cork.

The filming took place in the backdrop of some of the most intense years of the Troubles in Ireland, during which the Provisional Irish Republican Army (Provisional IRA) was waging an armed campaign in order to unite the island. On 30 January 1974, while filming in Dublin City's Phoenix Park, shooting had to be cancelled due to the chaos caused by 14 bomb threats.[16] One day a phone call was received and Kubrick was given 24 hours to leave the country; he left within 12 hours. The phone call alleged that the Provisional IRA had him on a hit list and Harlan recalls "Whether the threat was a hoax or it was real, almost doesn't matter ... Stanley was not willing to take the risk. He was threatened, and he packed his bag and went home."[6][5] Production of the film was one-third completed when this occurred, and it was rumored that the film would be abandoned. Nonetheless, Kubrick continued shooting the remainder of the film at locations in England, mainly southern England, Scotland and Germany.[12]

Locations in England include Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire; Castle Howard, North Yorkshire (exteriors of the Lyndon estate, "Castle Hickham"); Corsham Court, Wiltshire (various interiors and the music room scene); Petworth House, West Sussex (chapel); Stourhead, Wiltshire (lake and temple); Longleat, Wiltshire; Wilton House, Wiltshire (interior and exterior) and Lavenham Guildhall at Lavenham in Suffolk (amputation scene). Filming took place at Dunrobin Castle (exterior and garden as Spa) in Sutherland, Scotland. Locations in Germany include Ludwigsburg Palace near Stuttgart and Frederick II of Prussia's Neues Palais at Potsdam near Berlin (suggesting Berlin's main street Unter den Linden as construction in Potsdam had just begun in 1763).

Cinematography

The film, as with "almost every Kubrick film", is a "showcase for [a] major innovation in technique."[7] While 2001: A Space Odyssey had featured "revolutionary effects," and The Shining would later feature heavy use of the Steadicam, Barry Lyndon saw a considerable number of sequences shot "without recourse to electric light."[7] The film's cinematography was overseen by director of photography John Alcott (who won an Oscar for his work), and is particularly noted for the technical innovations that made some of its most spectacular images possible. To achieve photography without electric lighting "[f]or the many densely furnished interior scenes … meant shooting by candlelight," which is known to be difficult in still photography, "let alone with moving images."[7]

Kubrick was "determined not to reproduce the set-bound, artificially lit look of other costume dramas from that time."[7] After "tinker[ing] with different combinations of lenses and film stock," the production obtained three super-fast 50mm lenses (Carl Zeiss Planar 50mm f/0.7) developed by Zeiss for use by NASA in the Apollo Moon landings, which Kubrick had discovered.[7][19] These super-fast lenses "with their huge aperture (the film actually features the lowest f-stop in film history) and fixed focal length" were problematic to mount, and were extensively modified into three versions by Cinema Products Corp. for Kubrick to gain a wider angle of view, with input from optics expert Richard Vetter of Todd-AO.[7][19] The rear element of the lens had to be 2.5 mm away from the film plane, requiring special modification to the rotating camera shutter.[20] This allowed Kubrick and Alcott to shoot scenes lit in candlelight to an average lighting volume of only three candela, "recreating the huddle and glow of a pre-electrical age."[7] In addition, Kubrick had the entire film push-developed by one stop.[19]

Although Kubrick and Alcott sought to avoid electric lighting where possible, most shots were achieved with conventional lenses and lighting, but were lit to deliberately mimic natural light rather than for compositional reasons. In addition to potentially seeming more realistic, these methods also gave a particular period look to the film which has often been likened to 18th-century paintings (which of course depict a world devoid of electric lighting), in particular owing "a lot to William Hogarth, with whom Thackeray had always been fascinated."[7]

The film is widely regarded as having a stately, static, painterly quality,[7] mostly due to its lengthy, wide-angle long shots. To illuminate the more notable interior scenes, artificial lights called "Mini-Brutes" were placed outside and aimed through the windows, which were covered in a diffuse material to scatter the light evenly through the room rather than being placed inside for maximum use as most conventional films do. In some instances, the natural daylight was allowed to come through, which when recorded on the film stock used by Kubrick showed up as blue-tinted compared to the incandescent electric light.[21]

Despite such slight tinting effects, this method of lighting not only gave the look of natural daylight coming in through the windows, but it also protected the historic locations from the damage caused by mounting the lights on walls or ceilings and the heat from the lights. This helped the film "fit ... perfectly with Kubrick's gilded-cage aesthetic – the film is consciously a museum piece, its characters pinned to the frame like butterflies."[7][21]

Music

| Barry Lyndon | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by various | |

| Released | 27 December 1975 |

| Genre | Classical, folk |

| Length | 49:48 |

| Label | Warner Bros. |

| Producer | Leonard Rosenman |

The film's period setting allowed Kubrick to indulge his penchant for using classical music, and the film score includes pieces by Vivaldi, Bach, Handel, Paisiello, Mozart, and Schubert.[a] The piece most associated with the film, however, is the main title music, Handel's Sarabande from the Keyboard suite in D minor (HWV 437). Originally for solo harpsichord, the versions for the main and end titles are performed with strings, timpani, and continuo. The score also includes Irish folk music, including Seán Ó Riada's song "Women of Ireland", arranged by Paddy Moloney and performed by The Chieftains. "The British Grenadiers" also features in scenes with Redcoats marching.

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Performer/conductor/arranger | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Sarabande–Main Title" | George Frideric Handel | National Philharmonic Orchestra | 2:38 |

| 2. | "Women of Ireland" | Seán Ó Riada | The Chieftains | 4:08 |

| 3. | "Piper's Maggot Jig" | traditional | The Chieftains | 1:39 |

| 4. | "The Sea-Maiden" | traditional | The Chieftains | 2:02 |

| 5. | "Tin Whistles" | Ó Riada | Paddy Moloney & Seán Potts | 3:41 |

| 6. | "The British Grenadiers" | traditional | Fifes & Drums | 2:12 |

| 7. | "Hohenfriedberger March" | Frederick II of Prussia | Fifes & Drums | 1:12 |

| 8. | "Lillibullero" | traditional | Fifes & Drums | 1:06 |

| 9. | "Women of Ireland" | Ó Riada | Derek Bell | 0:52 |

| 10. | "March from Idomeneo" | Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart | National Philharmonic Orchestra | 1:29 |

| 11. | "Sarabande–Duel" | Handel | National Philharmonic Orchestra | 3:11 |

| 12. | "Lillibullero" | traditional | Leslie Pearson | 0:52 |

| 13. | "German Dance no. 1 in C major" | Franz Schubert | National Philharmonic Orchestra | 2:12 |

| 14. | "Sarabande–Duel" | Handel | National Philharmonic Orchestra | 0:48 |

| 15. | "Film Adaptation of the Cavatina from Il barbiere di Siviglia" | Giovanni Paisiello | National Philharmonic Orchestra | 4:28 |

| 16. | "Cello Concerto in E minor (third movement)" | Antonio Vivaldi | Lucerne Festival Strings/Pierre Fournier/Rudolf Baumgartner | 3:49 |

| 17. | "Adagio from Concerto for two harpsichords in C minor" | Johann Sebastian Bach | Münchener Bach-Orchester/Hedwig Bilgram/Karl Richter | 5:10 |

| 18. | "Film Adaptation of Piano Trio in E-flat, op. 100 (second movement)" | Schubert | Moray Welsh/Anthony Goldstone/Ralph Holmes | 4:12 |

| 19. | "Sarabande–End Title" | Handel | National Philharmonic Orchestra | 4:07 |

| Total length: | 49:48 | |||

Charts

| Chart (1976) | Position |

|---|---|

| Australia (Kent Music Report)[22] | 99 |

Certifications

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| France (SNEP)[23] | Platinum | 300,000* |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

Reception

Contemporaneous

The film "was not the commercial success Warner Bros. had been hoping for" within the United States,[7] although it fared better in Europe. In the US it earned $9.1 million.[24] Ultimately, the film grossed a worldwide total of $31.5 million on an $11 million budget.[2]

This mixed reaction saw the film (in the words of one retrospective review) "greeted, on its release, with dutiful admiration – but not love. Critics ... rail[ed] against the perceived coldness of Kubrick's style, the film's self-conscious artistry and slow pace. Audiences, on the whole, rather agreed".[7]

Roger Ebert gave the film three and a half stars out of four and wrote that it "is almost aggressive in its cool detachment. It defies us to care, it forces us to remain detached about its stately elegance." He added, "This must be one of the most beautiful films ever made."[25] Vincent Canby of The New York Times called the film "another fascinating challenge from one of our most remarkable, independent-minded directors."[26] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film three and a half stars out of four and wrote "I found Barry Lyndon to be quite obvious about its intentions and thoroughly successful in achieving them. Kubrick has taken a novel about a social class and has turned it into an utterly comfortable story that conveys the stunning emptiness of upper-class life only 200 years past."[27] He ranked the film fifth on his year-end list of the best films of 1975.[28]

Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times called it "the motion picture equivalent of one of those very large, very heavy, very expensive, very elegant and very dull books that exist solely to be seen on coffee tables. It is ravishingly beautiful and incredibly tedious in about equal doses, a succession of salon quality still photographs—as often as not very still indeed."[29] The Washington Post wrote, "It's not inaccurate to describe 'Barry Lyndon' as a masterpiece, but it's a deadend masterpiece, an objet d'art rather than a movie. It would be more at home, and perhaps easier to like, on the bookshelf, next to something like 'The Age of the Grand Tour,' than on the silver screen."[30] Pauline Kael of The New Yorker wrote that "Kubrick has taken a quick-witted story" and "controlled it so meticulously that he's drained the blood out of it," adding, "It's a coffee-table movie; we might as well be at a three-hour slide show for art-history majors."[31]

This "air of disappointment"[7] factored into Kubrick's decision for his next film, an adaption of Stephen King's The Shining, a project that would not only please him artistically, but was more likely to succeed financially.

Re-evaluation

Over time, the film has gained a more positive reaction.[8] On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 87% based on 84 reviews, with an average rating of 8.3/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Cynical, ironic, and suffused with seductive natural lighting, Barry Lyndon is a complex character piece of a hapless man doomed by Georgian society."[32] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 89 out of 100 based on reviews from 21 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[33] Roger Ebert added the film to his 'Great Movies' list on 9 September 2009 and increased his original rating from three and a half stars to four, writing, "Stanley Kubrick's Barry Lyndon, received indifferently in 1975, has grown in stature in the years since and is now widely regarded as one of the master's best. It is certainly in every frame a Kubrick film: technically awesome, emotionally distant, remorseless in its doubt of human goodness."[8]

The Village Voice ranked the film at number 46 in its Top 250 "Best Films of the Century" list in 1999, based on a poll of critics.[34] Director Martin Scorsese has named Barry Lyndon as his favourite Kubrick film,[35] and it is also one of Lars von Trier's favourite films.[36] Barry Lyndon was included on Time's All-Time 100 best movies list.[37] In the 2012 Sight & Sound Greatest Films of All Time poll, Barry Lyndon placed 19th in the directors' poll and 59th in the critics' poll.[38] The film ranked 27th in BBC's 2015 list of the 100 greatest American films.[39] In the 2022 Sight & Sound Greatest Films of All Time poll, Barry Lyndon placed 12th in the directors' poll and 45th in the critics' poll.[40]

In a list compiled by The Irish Times critics Tara Brady and Donald Clarke in 2020, Barry Lyndon was named the greatest Irish film of all time.[41]

The Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa cited the movie as one of his 100 favorite films.[42]

Awards and nominations

See also

- List of American films of 1975

- Overlord – the 1975 Stuart Cooper WWII film John Alcott also worked on

- Cinema of Ireland

Notes

References

- ^ a b "Barry Lyndon (A)". British Board of Film Classification. 26 November 1975. Archived from the original on 27 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ a b c "Barry Lyndon". IMDb. 18 December 1975.

- ^ "Barry Lyndon". British Film Institute Collections Search. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- ^ a b "Marisa Berenson on the making of Barry Lyndon: Kubrick wasn't a 'difficult ogre – he was a perfectionist'". The Independent. 13 July 2016. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ a b c Whitington, Paul (22 March 2015). "Kubrick in Ireland: the making of Barry Lyndon". The Independent. Archived from the original on 22 September 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ a b "Ryan O'Neal tells TEN about Kubrick's IRA fears". RTÉ. Archived from the original on 13 August 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Robey, Tim (27 July 2016). "Kubrick by candlelight: how Barry Lyndon became a gorgeous, period-perfect masterpiece". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 26 August 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d Roger Ebert (9 September 2009). "Technically awesome, emotionally distant, and classically Kubrick". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on 6 September 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ Charlie Graham-Dixon (8 August 2016). "Why Barry Lyndon is Stanley Kubrick's secret masterpiece". Dazed. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (28 July 2016). "Barry Lyndon review – Kubrick's intimate epic of utter lucidity". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 December 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ Ciment, Michel. "Kubrick on Barry Lyndon". Archived from the original on 5 May 2007. Retrieved 31 May 2007.

- ^ a b c d "Barry Lyndon". AFI Catalog. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ Saner, Emine (30 October 2019). "'I did the first nude in Vogue': Marisa Berenson on being a blazing star of the 70s and beyond: Interview". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 November 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ^ "Visual memory" (interview). UK. Archived from the original on 10 February 2010. Retrieved 7 March 2010.

- ^ "All hail Kubrick's 'Barry Lyndon,' a masterclass in bringing a unique filmmaker's vision to life • Cinephilia & Beyond". Cinephilia & Beyond. 9 April 2015. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ^ a b Pramaggiore, Maria (18 December 2014). Making Time in Stanley Kubrick's Barry Lyndon: Art, History, and Empire. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781441167750.

- ^ "John Alcott winning the Oscar® for Cinematography for "Barry Lyndon" – Oscars on YouTube". YouTube. 7 November 2012. Archived from the original on 8 August 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ "Barry Lyndon film locations". Movie-locations.com. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ a b c Two Special Lenses for "Barry Lyndon" Archived 13 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Ed DiGiulio (President, Cinema Products Corp.), American Cinematographer

- ^ Ciment, Michel. "Three Interviews with Stanley Kubrick". The Kubrick Site. Archived from the original on 4 July 2006. Retrieved 15 January 2007.

- ^ a b Herb A. Lightman (16 March 2018). "Photographing Stanley Kubrick's Barry Lyndon". American Cinematographer. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

In some instances, I let the natural blue daylight come through in the background without correcting it.

- ^ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. p. 282. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ "French album certifications – B.O.F. – Barry Lindon" (in French). Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique.

- ^ SECOND ANNUAL GROSSES GLOSS Byron, Stuart. Film Comment; New York Vol. 13, Iss. 2, (Mar/Apr 1977): 35-37, 64.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (20 September 1975). "Barry Lyndon". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on 18 December 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (19 December 1975). "Screen: Kubrick's 'Barry Lyndon' Is Brilliant in Its Images". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (26 December 1975). "'Barry Lyndon': Beauty and grace outweigh pace in a Kubrick classic". Chicago Tribune. Section 3, p. 1.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (4 January 1976). "Ten films outclass the publicity pitch". Chicago Tribune. Section 6, p. 2.

- ^ Champlin, Charles (19 December 1975). "A Rake's Lack of Progress". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 1.

- ^ "'Barry' Is All Dressed Up, but Going Where?" The Washington Post. 25 December 1975. H14.

- ^ Kael, Pauline (29 December 1975). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. 49.

- ^ "Barry Lyndon (1975)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 14 August 2015. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ "Critic Reviews for Barry Lyndon (1975)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ "Take One: The First Annual Village Voice Film Critics' Poll". The Village Voice. 1999. Archived from the original on 26 August 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2006.

- ^ Ciment, Michel; Adair, Gilbert; Bononno, Robert (1 September 2003). Kubrick: The Definitive Edition. Macmillan. p. vii. ISBN 9780571211081. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

I'm not sure if I can have a favourite Kubrick picture, but somehow I keep coming back to Barry Lyndon.

- ^ "It was like a nursery – but 20 times worse". The Guardian. 11 January 2004. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ Schickel, Richard (13 January 2010). "Barry Lyndon". Time. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ "Votes for Barry Lyndon (1975) | BFI". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest American Films". BBC. 20 July 2015. Archived from the original on 14 January 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ "Barry Lyndon (1975)". BFI. Archived from the original on 1 August 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ Brady, Tara; Clarke, Donald. "The 50 best Irish films ever made, in order". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ Thomas-Mason, Lee (12 January 2021). "From Stanley Kubrick to Martin Scorsese: Akira Kurosawa once named his top 100 favourite films of all time". Far Out Magazine. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ "The 48th Academy Awards | 1976". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. 4 October 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Film in 1976 | BAFTA Awards". awards.bafta.org. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Barry Lyndon". Golden Globe Awards. Archived from the original on 21 February 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "1st Annual Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards | 1975". Los Angeles Film Critics Association. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Award Winners | 1975". National Board of Review. Archived from the original on 25 May 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Past Awards | 1975". National Society of Film Critics. 19 December 2009. Archived from the original on 31 May 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

Further reading

- Tibbetts, John C., and James M. Welsh, eds. The Encyclopedia of Novels into Film (2nd ed. 2005) pp 23–24.

External links

- Barry Lyndon at IMDb

- Barry Lyndon at Rotten Tomatoes

- Barry Lyndon at the TCM Movie Database

- Barry Lyndon at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Barry Lyndon at the BFI's Screenonline

- Barry Lyndon: Time Regained an essay by Geoffrey O'Brien at the Criterion Collection

- Screenplay of Barry Lyndon (18 February 1973) at Daily script.

- Barry Lyndon Press Kit at Indelible Inc.

- The Kubrick Site, a "non-profit resource archive for documentary materials", including essays and articles.

- Stanley Kubrick’s letter to projectionists on Barry Lyndon at Some Came Running.

- 1975 films

- 1975 drama films

- 1970s American films

- 1970s British films

- 1970s German films

- 1970s Irish films

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s war drama films

- American war drama films

- British war drama films

- American films about gambling

- British films about gambling

- English-language war drama films

- Films about adultery

- Films based on British novels

- Films based on works by William Makepeace Thackeray

- Films directed by Stanley Kubrick

- Films produced by Stanley Kubrick

- Films with screenplays by Stanley Kubrick

- Films set in England

- Films set in Ireland

- Films set in Prussia

- Films set in the 1750s

- Films set in 1763

- Films set in 1773

- Films set in the 1780s

- Films set in the 18th century

- Films shot in County Wicklow

- Films shot in County Waterford

- Films shot in Dublin (city)

- Films shot at EMI-Elstree Studios

- Films shot in Germany

- Films shot in the Republic of Ireland

- Films shot in Scotland

- Films shot in North Yorkshire

- Films shot in Oxfordshire

- Films shot in Somerset

- Films shot in West Sussex

- Films shot in Wiltshire

- Films that won the Best Costume Design Academy Award

- Films that won the Best Original Score Academy Award

- Films whose art director won the Best Art Direction Academy Award

- Films whose cinematographer won the Best Cinematography Academy Award

- Films whose director won the Best Direction BAFTA Award

- Saturn Award–winning films

- Seven Years' War films

- Warner Bros. films