Hubert Chesshyre

Hubert Chesshyre | |

|---|---|

Chesshyre taking part in the Garter Day procession at Windsor Castle on 19 June 2006. | |

| Born | 22 June 1940 (age 84) |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | The King's School, Canterbury |

| Alma mater | |

| Occupation | Officer of Arms |

| Years active | 1970–2010 |

| Employer | Queen Elizabeth II |

| Organization | College of Arms |

| Notable work |

|

| Title | Clarenceux King of Arms |

| Term | 1997–2010 |

| Predecessor | John Brooke-Little |

| Successor | Patric Dickinson |

| Criminal charge | Non-recent child sexual abuse |

| Criminal penalty | Absolute discharge |

| Criminal status | Allegations proven in a trial of the facts |

| Awards |

|

David Hubert Boothby Chesshyre FSA FHS (born 22 June 1940) is a retired British officer of arms who also committed child sexual abuse offences.

Chesshyre served for more than forty years as an officer of arms in ordinary to Queen Elizabeth II and as a member of Her Majesty's Household. He was Clarenceux King of Arms, the second most senior member of the College of Arms and the second most senior heraldic position in England, Wales, Northern Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, and several other Commonwealth countries.[1] His other appointments included those of Registrar of the College of Arms, Secretary of the Order of the Garter, and Honorary Genealogist to the Royal Victorian Order. Chesshyre undertook heraldic and genealogical work for high-profile clients such as the former prime minister Sir Edward Heath. He has written seven books, including the official history of the Order of the Garter.

In October 2015, a jury sitting at Snaresbrook Crown Court found by a unanimous verdict that Chesshyre had committed child sexual abuse offences in the 1990s. He was found to be unfit to plead, and his trial was therefore a trial of the facts. This means that no formal conviction is recorded and Chesshyre was therefore given an absolute discharge.

Education and early career

Chesshyre was educated at St Michael's Preparatory School, Otford, where he was a contemporary of John Hurt[2] and a pupil of Roy Martin Haines. He went on to The King's School, Canterbury (The Grange 1954–59). He maintains a close relationship with The King's School. In 2010 he helped design a tie for the school's Legacy Club, a club for Old King's Scholars pledging a proportion of their estate to the school. The tie is blue scattered with silver mitres and golden crowns, reflecting the dual influence of Church and State on the school and the ways in which OKS have served both Church and State in return.[3] As recently as 2018, Chesshyre was a guest at the school's King's Week Lunch.[4]

Chesshyre undertook his undergraduate education at Trinity College, Cambridge, taking a BA in French and German which was later upgraded to an MA according to a tradition of the university. He is now a member of the Great Court Circle of Trinity College.[5] After graduating from Cambridge Chesshyre spent about four years working as a schoolmaster and vintner, including working for Moët et Chandon and John Harvey & Sons. He then studied at Christ Church, Oxford, where he was awarded a Diploma in Education in 1967.[6] In his book The Changing Anatomy of Britain, Anthony Sampson wrote, "Christ Church maintains its traditional disdain for twentieth-century activities, with an annual newsletter which reads like a parody of British snobberies, beginning with honours, Lords Lieutenants and royal service ('Mr D. H. B. Chesshyre, formerly Rouge Croix Pursuivant, aptly became Chester Herald of Arms'), and ending with vulgar achievements in business, journalism and sport."[7]

Chesshyre served in the Honourable Artillery Company from 1964 until 1965.[8] During this time he fired the 19-gun salute at the Tower of London for the state funeral of Winston Churchill.[6]

Heraldic career

Having received his Diploma in Education from Oxford, Chesshyre did not enter the teaching profession, but instead was appointed in 1967 to a position as an assistant at the College of Arms.[9] He was a Green Staff Officer at the Investiture of the Prince of Wales in 1969. Appointed a member of the Chapter of the College of Arms the following year, he served as Rouge Croix Pursuivant (1970–78),[10] Chester Herald (1978–95),[11] Norroy and Ulster King of Arms and Principal Herald of the North part of England and of Northern Ireland (1995–97),[12] and Clarenceux King of Arms and Principal Herald for the South, East and West parts of England (1997–2010).[13] From 1971 until 1978 he also served on the staff of Anthony Wagner. He was Registrar of the College of Arms from 1992 until 2000 and was the Founder Secretary of the College of Arms Uniform Fund in 1980, serving in that capacity until 1999.[14]

Interviewed by Robert Hardman for The Daily Telegraph in an article about the arms of Margaret and Denis Thatcher, Chesshyre observed, "A herald gets £17.80 per annum from the Queen. We did get a 100 per cent pay rise in 1617 but they reduced it again in 1831. We get part of the client's fee but it's not a job you do for the money." Hardman joked, "Lady Thatcher would approve of the college's anti-inflationary wages scheme."[15]

Chesshyre was Secretary of the Order of the Garter from 1988 until 2003, having been trained for the role by his predecessor Walter Verco and by Verco's predecessor-but-one, Anthony Wagner. Upon his resignation Chesshyre had an audience with The Queen at Buckingham Palace, during which he surrendered his badge of office.[16] Following the 1992 Windsor Castle fire Chesshyre was, together with Peter Begent, appointed heraldic consultant for the reconstruction of St George's Hall.[17] Chesshyre was also Honorary Genealogist of The Society of the Friends of St George's and Descendants of the Knights of the Garter.[18]

Chesshyre served for twenty-three years as Honorary Genealogist to the Royal Victorian Order (1987–2010), again, succeeding Walter Verco.[8][19]

As Ulster King of Arms (merged with Norroy) Chesshyre also held the technically extant position of King of Arms, Registrar, and Knight Attendant of the Order of St Patrick. He was therefore briefly one of just two members of the Order of St Patrick, the other member being Queen Elizabeth II, who remains Sovereign of the Order.[20][21][22]

From early in his career Chesshyre from time to time served as a deputy to Garter Principal King of Arms for the purpose of introducing peers into the House of Lords. For example, in 1975 he introduced Baroness Vickers.[23]

Towards the end of his career Chesshyre was assisted by Robert Harrison, CStJ, a member of the Journal Office at the House of Lords.[24]

Chesshyre retired from the College of Arms on 31 August 2010.[25] His last public duties took place at the State Opening of Parliament on 25 May 2010 and at the Garter Day ceremony on 14 June 2010. Commentating on the State Opening for the BBC, Huw Edwards remarked upon Chesshyre's forty years of service.[26]

Heraldic clients

This is a list of just some of the clients for whom Chesshyre acted as "agent" at the College of Arms.

Personal clients

- The Revd Dr D.W.H. Arnold, ChStJ, Principal of St Chad's College, University of Durham 1994–97[27]

- Raymond Arnold[28]

- The Rt Hon John Bercow, MP, Speaker of the House of Commons since 2009[2]

- The Rt Hon Baroness Boothroyd, OM, PC, Speaker of the House of Commons 1992–2000, Chancellor of the Open University 1994–2006[27]

- Alan Lonsdale Buttifant[29]

- The Rt Revd and Rt Hon Lord Chartres, KCVO, ChStJ, PC, DD, Bishop of London, Prelate of the Order of the British Empire, and Dean of the Chapels Royal 1995–2017, crossbench peer since 2017[30]

- The Venerable Peter Delaney, MBE, Archdeacon of London 1999–2009 (now Emeritus), Past Master of the Worshipful Company of Gardeners and Worshipful Company of World Traders[31]

- Sir (Francis) Herbert du Heaume, CIE, OBE, KPM, upon whom was also conferred the Indian Police Medal, Deputy Inspector General of Police in British India 1942–47.[32]

- Sir Ewen Fergusson, GCMG, GCVO, Grand Officier Légion d'honneur, UK Ambassador South Africa 1982–84 and France 1987–92, Deputy Under Secretary of State Foreign and Commonwealth Office 1984–87, King of Arms of the Most Distinguished Order of St Michael and St George 1996–2007.[33][34]

- Dr Malcolm Golin[35][36]

- Rear Admiral Sir Donald Gosling, KCVO, KStJ, President of the White Ensign Association 1993–, Vice-Admiral of the United Kingdom 2012–. Joint Chairman of National Car Parks 1950–98.[citation needed]

- The Rt Hon Sir Edward Heath, KG, MBE, Leader of the Conservative Party 1965–75, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom 1970–74, Father of the House of Commons 1992–2001[37]

- Paul Holmer, CMG, UK Ambassador Ivory Coast, Upper Volta, and Niger 1972–75 and Romania 1979–83, Minister and Deputy Permanent Representative to NATO 1976–79.[32]

- The Rt Revd and Rt Hon Lord Hope of Thornes, KCVO, PC, Bishop of Wakefield 1985–91, Bishop of London, Prelate of the Order of the British Empire, and Dean of the Chapels Royal 1991–95, Archbishop of York, Primate of England, and Metropolitan 1995–2005, Judge of the Court of Ecclesiastical Causes Reserved 2006–11[38]

- Sir Robert Horton, Chairman of British Petroleum 1990–92, Chairman of Railtrack 1993–99, Chancellor of the University of Kent 1990–95 (contemporary with Chesshyre at the King's School, Canterbury, of which he was governor 1984–2005 and governor emeritus 2005–11)[39]

- Malcolm Howe, Lord of the Manor of Sharples[40][41]

- Sir John Hurt, CBE, actor (Chesshyre's contemporary at St Michael's Preparatory School, Otford and friend)[2]

- Brian North Lee, founder of the Bookplate Society, author of more than thirty books on bookplates.[42][43]

- Sir Paul McCartney, MBE[44]

- Professor John Morehen, JP, FRCO, FRCCO, Hon FGCM, Master of the Worshipful Company of Musicians[45]

- The Very Revd Dr John Moses, KCVO, Dean of St Paul's and of the Orders of St Michael and St George and of the British Empire 1996–2006[citation needed]

- The Rt Hon Lord Palumbo, Chairman Tate Gallery Foundation 1986–87, Arts Council of Great Britain 1989–94, and Serpentine Gallery 1994–, Chancellor of the University of Portsmouth 1992–2007[46]

- The Rt Revd Dr Stephen Platten, Minister Provincial of the European Province of the Third Order of Saint Francis 1991–96, Dean of Norwich 1995–2003, Bishop of Wakefield 2003–14[2]

- Kenneth Porter[47][48]

- Sir Terry Pratchett, OBE[2]

- Dr Andreas Prindl, CBE, deputy chairman and member of the Council of Lloyd's, Visiting Professor in the Renmin University of China, and governor of the Yehudi Menuhin School. Formerly chairman and managing director of Nomura Bank International, President of the Chartered Institute of Bankers, President of the Association of Corporate Treasurers, Provost of Gresham College, and Master of the Worshipful Company of Musicians[citation needed]

- Mr Michael Pugh, FRCS, FRCOG, Master of the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries 1997/8[49]

- Dr Bernard Rose, OBE, Lecturer in Music, University of Oxford 1950–81 (Choragus 1958–63), Fellow, Organist, and Informator Choristarum, Magdalen College, Oxford 1957–81 (Vice-President 1973–1975), President of the Royal College of Organists 1974–76[citation needed]

- The Rt Hon Lord Sugar, founder of Amstrad, star of The Apprentice, member of the House of Lords[2]

- Michael Wade, Treasurer of the Conservative Party[citation needed]

Corporate clients

Ecclesiastical

- Dean of St Paul's (formal grant of traditional arms)[citation needed]

Civic

- Blacktown City Council, New South Wales, Australia[50][51]

- The Borough Council of King's Lynn and West Norfolk[52]

Academic

- College of Estate Management (now University College of Estate Management)[53]

- Highgate School[54]

- Institution of Mining and Metallurgy[55]

- Monkton Combe Junior School (now Monkton Combe Preparatory School) (badge only)[56][57]

- Monkton Combe School (formal grant of traditional arms)[56][57]

- University of Glamorgan[citation needed]

Organisational

- Federation of Family History Societies[58]

- Worshipful Company of Bowyers (supporters only)[59]

Commercial

- Goodwin PLC [60]

Genealogical clients

In the autumn of 1983 Chesshyre undertook genealogical research for the Rt Hon Michael Heseltine, MP, then Secretary of State for Defence. He succeeded in tracing Heseltine's ancestors down to the end of the eighteenth century, but dropped his enquiries after Heseltine was informed that further research would cost him £350.[61] Between 1970 and 1975 Chesshyre also undertook work on behalf of the Rt Hon Sir Peter Rawlinson, QC, MP, Attorney General for England and Wales and Attorney General for Northern Ireland.[62]

Professional achievements

Chesshyre served as heraldic advisor to the committee that organised the re-enactment of the funeral of Arthur, Prince of Wales in Worcester on 3 May 2002. On the day of the re-enactment, Chesshyre processed through the streets of Worcester bearing Arthur's crested helm, followed by other heralds bearing his sword, tabard, gauntlets, and spurs.[63]

In 2006 Chesshyre was a delegate to the 27th International Congress of Genealogical and Heraldic Sciences at St Salvator's College, University of St Andrews, held in the presence of Anne, Princess Royal.[64]

Chesshyre has enjoyed a long professional association with Westminster Abbey. In 1973 he completed at the request of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster Abbey a report entitled "The Restoration of the Regalia to the Tomb of Queen Elizabeth the First in Westminster Abbey: Research into the Identity of the Collar Missing from the Queen's Marble Effigy". He found "that there was no clear evidence that the missing collar was a Garter collar, suggesting instead that "the 'Three Brothers' pendant and collar shown in the Ermine portrait of Queen Elizabeth as a suitable model for the restoration".[65][66] He was later a member of the Abbey's Architectural Advisory Panel, from 1985 until 1998, and then of its Fabric Commission, from 1998 until 2003. Chesshyre was also heraldic advisor for the west window of the Henry VII Lady Chapel, donated by John Templeton and devised by Donald Buttress, which The Queen unveiled on 19 October 1995.[67][68]

Chesshyre has worked as a freelance lecturer in the United Kingdom and abroad. For many years he lectured for the National Association of Decorative and Fine Arts Societies and Speaker Finders.[8]

On 1 October 2005 Chesshyre appeared at the Windsor Festival, introducing Roy Strong.[69]

A Cambridge graduate in German, Chesshyre was interviewed in 1981 for a story in Der Spiegel. He explained that heraldry had begun in the twelfth century when kings and noblemen had decorated their shields with mythical creatures in order to intimidate their opponents both in tournaments and in battle. He observed that medieval heraldic animals were typically depicted with very large sexual organs and also commented on the figure of a naked woman depicted on the Hanoverian coat of arms of Ireland.[70]

Chesshyre has been credited with establishing the probable origins of the common error of using the term crest to refer to the whole achievement. He explains that in the 18th century it was common for smaller items, such as spoons and forks, to be engraved with the crest alone, while the full achievement was reserved for larger items such as salvers. For this reason a number of publications appeared from the late 18th century through to the early 20th century which recorded only crests. Chesshyre later successfully lobbied the chief revise editor of The Times to include an explanation of the precise meaning of the term crest in a new edition of the newspaper's staff manual.[71]

Scholarly publications

The Most Noble Order of the Garter, which Chesshyre co-authored with Peter Begent and Lisa Jefferson, enjoyed the distinction of a foreword by Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (p. 2) and of being 'Dedicated with permission to|Her Most Gracious Majesty Queen Elizabeth II|Thirtieth Sovereign of the Order' (p. 4). One of the book's reviewers, John Goodall, wrote that it had been 'eagerly awaited' and was 'the most comprehensive' study of the subject since that of Elias Ashmole, and he wrote that it was "unlikely to be superseded".[72] Another reviewer, Maurice Keen, wrote that it was "invaluable to scholars whose interests touch on the history of the order, from the widest variety of points of view and period specialisation", and that "Altogether, Peter Begent and Hubert Chesshyre have put together a volume that for its thoroughness, its interest and its physical attraction is a worthy tribute to the longevity of England's highest order of chivalry."[73]

M. K. Ridgway, reviewing The Identification of Coats of Arms on British Silver, wrote that Chesshyre "has the undoubted gift of making a difficult and complicated subject both exciting and interesting".[74]

In the early 1970s Chesshyre met the distinguished architect Thomas Saunders when Chesshyre and one of his brothers unsuccessfully competed with Saunders to bid for a property in Bethnal Green, 17 Old Ford Road. Four years after he had purchased the property, Saunders contacted Chesshyre with a commission to write a history of Bethnal Green, with particular reference to the legend of the Blind Beggar.[75] This resulted in The Green, co-authored with A. J. Robinson, which was later described by Victor E. Neuburg as "The best—indeed only—comprehensive account of the subject".[76] During the period around 1970 to 1980 Chesshyre wrote another book on the history of Bethnal Green, Number Seventeen, or the History of 17 Old Ford Road, Bethnal Green and the Natt Family. Although complete, the book has never been published, but a copy is held, together with notes, maps, and correspondence, at the Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives.[77]

Music

Chesshyre was a choral clerk of Trinity College, Cambridge during his time as an undergraduate at the college.[6] From 1979 until 1993 Chesshyre was a member of The Bach Choir, of which he is now an Associate Member.[78] Chesshyre now sings for the London Docklands Singers, which he joined in 2002. He has been, since 1980, a member of the Madrigal Society, the oldest musical society in Europe (see Madrigal). He became a Freeman of the Worshipful Company of Musicians in 1994 and a Liveryman of the Company in 1995.[8]

Honours

Chesshyre was appointed a Lieutenant of the Royal Victorian Order (LVO) in the Queen's Birthday Honours of 11 June 1988[79] and was promoted to be a Commander of the Order (CVO) in the New Year Honours of 31 December 2003.[80] Chesshyre was also awarded the Queen Elizabeth II Silver Jubilee Medal in 1977 and the Queen Elizabeth II Golden Jubilee Medal in 2002.[81][82][83][84][85] Chesshyre's appointment to be a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order was cancelled and annulled with effect from Tuesday 15 May 2018.[86]

Chesshyre became a Freeman of the City of London in 1975.[8]

Chesshyre was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London in 1977 and was a member of its heraldry committee, known as the Croft Lyons Committee.[87] Since 1983 he has been a member of the Cocked Hat Club, the senior dining club of the Society of Antiquaries, serving as praeses (president) in 1986.[18]

Chesshyre was a member of the Council of the Heraldry Society from 1973 until 1985,[88] and he was elected a Fellow of the Society on 7 February 1990.[89] Election to the Fellowship recognises "outstanding achievement in connection with the art and science of heraldry"[90] or "armory, chivalry, precedence, ceremonial, genealogy, family history, and all kindred subjects".[91] The Society has 24 Fellows, of whom Chesshyre ranks fourth in seniority by date of election.[89]

Chesshyre served as Vice-President of the Institute of Heraldic and Genealogical Studies (IHGS)[92] and was a Director of the IHGS until 31 December 1993.[93] However, after his sexual offences and the forfeiture of his main honour came to light, his name was removed from the list of vice-presidents on the IHGS website.[94] On 23 November 2019 an article in The Observer confirmed that the "trustees promptly removed him as vice-president" after his sex offending became public knowledge earlier in the year.[95]

Chesshyre has been honoured with the titles of associate member of the Society of Heraldic Arts[96] and honorary member of the White Lion Society.[97] He was also the Patron of the now defunct Middlesex Heraldry Society.[98]

In 1998 the Cambridge University Heraldic and Genealogical Society appointed Chesshyre to deliver its annual Mountbatten Memorial Lecture[99] (Louis Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma was President of the Cambridge University Society of Genealogists and Patron of CUHAGS). Two years later, Chesshyre was a guest of honour (together with the Master of Fitzwilliam College, representing the Vice-Chancellor, the Deputy Mayor of the City of Cambridge, Garter Principal King of Arms, York Herald, and the Chairman of the Federation of Family History Societies) at the CUHAGS Fiftieth Annual Dinner held in the Great Hall of Clare College on 25 March 2000.[100][101]

Appearance and personality

Chesshyre is mentioned in the diaries of James Lees-Milne,[when?] who described him as "handsome though over fifty, and charming to talk to".[102]

Health

By the time of his criminal trial in October 2015, Chesshyre had suffered a stroke and was suffering from dementia.[103]

Child sexual abuse and honours forfeiture

Chesshyre was charged with non-recent offences of child sexual abuse and in October 2015 stood trial before a jury sitting at Snaresbrook Crown Court. The offences pertained to a single complainant—a male aged in his teens—and took place during the 1990s.[104] He was determined to be unfit to plead due to a stroke and dementia. The trial therefore went ahead as a trial of the facts.[103] The jury found unanimously that he had committed two of the offences charged against him on the indictment. However, no conviction is formally recorded and the court consequently granted him an absolute discharge. The Honours and Appointments Secretariat, which is part of the Cabinet Office, said in evidence to the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse that it "takes the view that the outcome of the trial holds equivalent weight to a full criminal investigation [and hence a criminal conviction]."[104]

Despite a criminal finding of fact having been made, Sir Alan Reid, GCVO, Secretary of the Royal Victorian Order, refused to recommend the forfeiture of Chesshyre's appointment to the Order (CVO), stating that Chesshyre had not technically been convicted and that he had been given an absolute discharge.[103] Reid's decision was later overturned and Chesshyre's award was at last forfeited with effect from 15 May 2018.[86] The eventual forfeiture followed an appeal by the victim's MP, which led to the Prime Minister, Theresa May, seeking to have the original decision reviewed by an independent committee. Unusually, however, the forfeiture was not notified in the London Gazette, which is normally the standard procedure in these cases. Chesshyre still holds almost all of the many other honours conferred upon him throughout his career, despite calls for these, too, to be revoked. The case avoided wide public knowledge, in part because Chesshyre's name was misspelled in court documents throughout his legal process, until March 2019, when it was mentioned at a public hearing of the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse, which led in turn to an article in The Observer newspaper.[104][103] According to journalist Jamie Doward, "When approached by the Observer, the various societies of which he [Chesshyre] is a member confirmed that they would not be dissociating themselves from him."[103]

After Chesshyre's sex offending became public knowledge in March 2019, a number of fellows of the Society of Antiquaries of London contacted the society to request that Chesshyre should be removed from the society's fellowship. As required by the society's statutes, the society's council proposed a resolution seeking Chesshyre's removal from the fellowship. However, the fellows present at the meeting voted "by a substantial majority" to reject the resolution and therefore to keep Chesshyre on as a fellow of the society. In a statement, the council said that it "regrets that a majority of those present did not see fit to support the resolution" and were said to be "dismayed" by the outcome.[95]

Ancestry

In the patrilineal line Chesshyre belongs to the family of Isacke of North Foreland Lodge. On 4 and 5 July 1938, respectively, Chesshyre's father, Captain Hubert Chesshyre, RE (later a colonel),[105] and uncle, Neville Chesshyre (later a brigadier and a Military CBE),[106] executed, attested, and enrolled deeds at the College of Arms changing their surname from Isacke to Chesshyre. Colonel Chesshyre was the son of Major General Hubert Isacke, CB, CSI, CMG, six times mentioned in despatches, late Queen's Own Royal West Kent Regiment. Major General Chesshyre's father was Colonel Henry Isacke, late RA, himself the son of Robert Isacke, Deputy Lieutenant of the County of Kent, sometime Commander in the Honourable East India Company Maritime Service.[107]

Robert Isacke's wife, Chesshyre's 2nd-great-grandmother, Matilda Scrymgeour-Wedderburn, was the daughter of Henry Scrymgeour-Wedderburn, de jure 7th Earl of Dundee, and great-granddaughter of Charles Maitland, 6th Earl of Lauderdale, through his son Captain the Hon Frederick Maitland, RN. Chesshyre has written that he is proud, as an English herald, to be related, through his 2nd-great-grandmother, to both the Bearer of the Royal Banner (Alexander Scrymgeour, 12th Earl of Dundee) and the Bearer of the National Flag of Scotland (Ian Maitland, 18th Earl of Lauderdale).[107]

Through Henry Isacke's wife, Louisa Chesshyre, subsequent generations of the family are descended from the family of Chesshyre of Barton Court, Canterbury. Louisa Chesshyre's father was the Reverend William Chesshyre, Rector of Canterbury St Martin and St Paul, Rural Dean of Canterbury, Proctor in Convocation for the Diocese of Canterbury, and Canon of Canterbury Cathedral. Canon Chesshyre's father was Vice-Admiral of the Blue John Chesshyre.[107][108][109] Through this common ancestry Chesshyre is a first cousin twice removed of the Law Lord Lord Tomlin.[110]

Through his paternal grandmother Ada Layard, Chesshyre is also descended from the Huguenot family of de Layarde, anglicised as Layard.[111] Chesshyre's great-grandfather in this line is Sir Charles Layard, who was Attorney General of Ceylon 1892–1902 and Chief Justice of Ceylon 1902–1906, and was himself the son of Sir Charles Layard, KCMG, Government Agent for the Western Provinces of Ceylon 1851–78, himself in turn the grandson in the maternal line of Gualterus Mooyaart, Administrator of Jaffna for the Dutch East India Company. Another of Chesshyre's 3rd-great-grandfathers in this line was Lieutenant Colonel Clement Edwards, Assistant Military Secretary to Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany, son-in-law of his 4th-great-grandfather the Very Reverend Dr Charles Layard, FRS, Dean of Bristol 1800–03, himself the son of Daniel Layard, DCL, DM, LCP, FRS. The family was established in England by Chesshyre's 6th-great-grandfather Pierre de Layarde, of Monflanquin, who attended William, Prince of Orange during the Glorious Revolution, eventually attaining the rank of Major, settled at Canterbury, and became a British subject in 1713, adopting the name Peter Layard. Appropriately, Peter Layard married his wife Marie Anne Crozé on 2 March 1716/17 at the church of St Benet's, Paul's Wharf, the church of the College of Arms.[112][113]

Through his mother, Katharine Boothby, daughter of Major Basil Boothby, RE, Chesshyre's 3rd-great-grandfather was Major Sir William Boothby, 7th baronet, 51st (2nd Yorkshire West Riding) Regiment of Foot, and Chesshyre is therefore a relation of the Boothby baronets of Broadlow Ash. Chesshyre's uncle, his mother's brother, was Basil Boothby, CMG, who served as British ambassador to Iceland and married Susan Asquith, a granddaughter of the Prime Minister H. H. Asquith.[114]

Chesshyre is the 10th-great-grandson of Henry Stanley, 4th Earl of Derby (1485 creation), by his illegitimate son also called Henry Stanley. He is in turn descended from Edward Stanley, 3rd Earl of Derby, who in 1555 presented Derby Place to the Crown as the home of the Heralds' College (now the College of Arms). Chesshyre is therefore also the 12th-great-grandson of John Howard, 1st Duke of Norfolk (1483 creation), himself the grandson of Thomas de Mowbray, 1st Duke of Norfolk (1397 creation), grandson of Margaret, Duchess of Norfolk (1397 creation suo jure for life), granddaughter of Edward I of England. Chesshyre is appropriately a relation of the Lords and Earls Marshal and Hereditary Marshals of England, who are the heads of the College of Arms, where he was an officer for so many years, and of many Knights and Ladies of the Order of the Garter, of which he was Secretary.[115] Through his Derby ancestors, Chesshyre is descended from many of the rulers of medieval Europe, including Rurik, the possibly legendary founder of Russia.

Chesshyre is also a kinsman of Sir John Chesshyre (1662–1738), Prime Serjeant at Law to Queen Anne and King George I. It was his inheriting a portrait of Sir John that sparked Chesshyre's interest in genealogy.[116] In 1976 Chesshyre attended the ceremony to mark the reopening of the Chesshyre Library, Halton, Cheshire, founded by Sir John in 1733. To mark the occasion a painting of the arms of Sir John and Lady Chesshyre, donated by the Chesshyre family, and produced by the College of Arms, was presented to the library.[117]

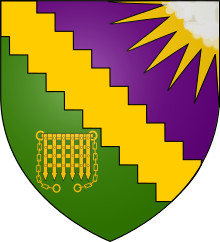

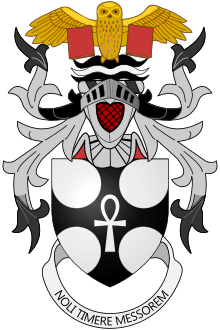

Coat of arms

|

|

List of publications

Books

- Carl Alexander von Volborth, Heraldry of the World, ed. D. H. B. Chesshyre, translated into English by Bob and Inge Gosney (London: Blandford Press, 1973)

- Hubert Chesshyre, The Identification of Coats of Arms on British Silver, drawings by Margaret J. Clark (London: Hawkslure Publications, 1978)

- A. J. Robinson and D. H. B. Chesshyre, The Green: A History of the Heart of Bethnal Green and the Legend of the Blind Beggar (1st edn., London: Borough of Tower Hamlets, 1978; 2nd edn., London: London Borough of Tower Hamlets, Central Library, 1986)

- Hubert Chesshyre and Adrian Ailes, Heralds of Today: A Biographical List of the Officers of the College of Arms, London, 1963–86, with a foreword by the Duke of Norfolk, KG, Earl Marshal of England (Gerrards Cross: Van Duren, 1986)

- D. H. B. Chesshyre and Thomas Woodcock, eds., Dictionary of British Arms: Medieval Ordinary vol. 1 (London: Society of Antiquaries of London, 1992)

- Hubert Chesshyre, Garter Banners of the Nineties (Windsor: College of Arms, 1998)

- Peter J. Begent and Hubert Chesshyre, The Most Noble Order of the Garter: 650 years, with a foreword by His Royal Highness the Duke of Edinburgh KG and a chapter on the statutes of the Order by Dr Lisa Jefferson (London: Spink, 1999)

- Hubert Chesshyre and Adrian Ailes, Heralds of Today: A Biographical List of the Officers of the College of Arms, London, 1987–2001, with a foreword by the Earl of Arundel (London: Illuninata, 2001)

Book chapters

- D. H. B. Chesshyre, "The Most Noble Order of the Garter", in The Orders of the Thistle and the Garter (Kinross, 1989), pp. 27–46

- Anthony Harvey and Richard Mortimer, eds., The Funeral Effigies of Westminster Abbey (Woodbridge: Boydell, 1994; rev. edn. 2003) [contribution]

- D. H. B. Chesshyre, "The Modern Herald", in Patricia Lovett, The British Library Companion to Calligraphy, Illumination and Heraldry: A History and Practical Guide (London: British Library, 2000), pp. 257–268

- Peter Begent, Hubert Chesshyre, and Robert Harrison, "The Heraldic Windows of St George's Chapel", in A History of the Stained Glass of St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, ed. Sarah Brown (Historical monographs relating to St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, vol. 18; Windsor: Dean and Canons of Windsor, 2005)

Reference work articles

- Stephen Friar, ed., A Dictionary of Heraldry (New York: Harmony Books, 1987) (author of articles on "Garter, Order of", pp. 160–2; "Grant of Arms", pp. 171–2; "Pedigrees, Proof and Registration of", pp. 264–5)

- D. H. B. Chesshyre, "Sir Edward Walker (1612–1677)", The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004)

Journal articles

- P. J. Begent and D. H. B. Chesshyre, "The Fitzwilliam Armorial Plate in St George's Chapel, Windsor", The Coat of Arms, NS 4 (1980–82), no. 114, pp. 269–74

- P. J. Begent and D. H. B. Chesshyre, "The Spencer-Churchill Augmentations", The Coat of Arms, NS 6 (1984–86), no. 134, pp. 151–5

- D. H. B. Chesshyre, "Canting Heraldry", The Coat of Arms, NS 7 (1987–89), no. 138, pp. 29–31

- Hubert Chesshyre, "The Heraldry of the Garter Banners", Report of the Society of the Friends of St George's and the Descendants of the Knights of the Garter, vol. VII, no. 6 (1994/5), pp. 245–55

- In addition to the above, Chesshyre was also formerly a regular contributor to the journal British History Illustrated

Book reviews

- D. H. B. Chesshyre, review of Richard Marks and Ann Payne, eds., British Heraldry from its Origins to c. 1800 (London: British Museum Publications, 1978), The Antiquaries Journal, vol. 59, issue 2 (1979), pp. 460–461

- D. H. B. Chesshyre, review of G. D. Squibb, Precedence in England and Wales (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981), The Antiquaries Journal, vol. 62, issue 2 (1982), pp. 435–436

Unpublished MSS

- D. H. B. Chesshyre, M.A., Rouge Croix Pursuivant of Arms, "Number Seventeen, or the History of 17 Old Ford Road, Bethnal Green and the Natt Family" (Unpublished MS, c. 1970–80; Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives L.6160 (class 040))

- David Hubert Boothby Chesshyre, FSA, Rouge Croix Pursuivant, "The Restoration of the Regalia to the Tomb of Queen Elizabeth the First in Westminster Abbey: Research into the Identity of the Collar Missing from the Queen's Marble Effigy" (Unpublished MS, 1973; The National Archives SAL/MS/852)

External links

Chesshyre in uniform with his successor Patric Dickinson

Short film about heraldry featuring Chesshyre and others

References

- ^ College of Arms Home Page. Accessed 23 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f 'News of OKS', in For the Record [published by the OKS Association], No. 15 (May 2012), p. 1.

- ^ 'The Legacy Club', O[ld] K[ing's] S[cholars] Offcuts, no. 29 (May 2010) (scroll to page 5). Archived 27 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 'The King’s Week Lunch - 2018' (.docx file). Website of The OKS Association. Accessed 23 November 2019.Archived 23 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Trinity College, Cambridge, Annual Report 2017–18 (Alumni Relations and Development Office), p. 30.

- ^ a b c Who's Who 2010 (162nd year of issue) (London: A. & C. Black, 2009), s.v. 'Chesshyre, David Hubert Boothby' (p. 418).

- ^ Anthony Sampson, The Changing Anatomy of Britain (New York: Random House), p. 146.

- ^ a b c d e Debrett's People of Today, s.v. Chesshyre, David Hubert Boothy.

- ^ College of Arms Newsletter, no. 26 (September 2010).

- ^ "No. 45066". The London Gazette. 24 March 1970. p. 3415.

- ^ "No. 47659". The London Gazette. 9 October 1978. p. 11997.

- ^ "No. 54085". The London Gazette. 27 June 1995. p. 8847.

- ^ "No. 54755". The London Gazette. 2 May 1997. p. 5289.

- ^ Heralds of Today (2nd edn.), p. 11.

- ^ Robert Hardman, "His and Her coats of arms for a baronet and his Lady", The Electronic Telegraph. Accessed 19 May 2010.

- ^ College of Arms Newsletter, no. 1 (May 2004).

- ^ Peter J. Begent and Hubert Chesshyre, The most noble Order of the Garter 650 years, with a foreword by His Royal Highness the Duke of Edinburgh KG and a chapter on the statutes of the Order by Dr Lisa Jefferson (London: Spink, 1999), p. 300.

- ^ a b Heralds of Today (2nd edn.), p. 12.

- ^ The London Gazette no. 51108 (2 November 1987), 13495.

- ^ Ronald Allison and Sarah Riddell, The Royal Encyclopedia (London: Macmillan, 1991), p. 356.

- ^ Peter Galloway, The Most Illustrious Order: The Order of St Patrick and its Knights (2nd edn., Unicorn, 1999), p. 211.

- ^ Brian Hoey, At Home with the Queen: Life Through the Keyhole of the Royal Household (London: HarperCollinsPublishers, 2003), p. 268.

- ^ Antony Hodgson, 'The College of Arms', Hand in Hand: International Journal of the Commercial Union Assurance Company, vol. 3, no. 5 (June 1980), 16–23 (20, with illustration).

- ^ Birmingham & Midland Society for Genealogy & Heraldry London Branch Newsletter, vol. 16 (1 January 2015), p. 2. Archived 27 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Clarenceux King of Arms, What's New, College of Arms website. Accessed 3 September 2010". Archived from the original on 24 December 2010. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ^ The State Opening of Parliament – 2010 (Huw Edwards presents live coverage of the 2010 State Opening of Parliament. HM The Queen attends the ceremony for the 59th time, as a combination of pageantry and politics launches the first session of the new Parliament.) Broadcast on: BBC One, 10:30am Tuesday 25 May 2010. Duration: 120 minutes. Available until: 12:29pm Tuesday 1 June 2010. Categories: Factual, Politics. Chesshyre is mentioned 47 minutes into the broadcast.

- ^ a b The Heraldry Gazette, NS 53 (September 1994), p. 6

- ^ The Heraldry Gazette, NS 72 (June 1999), p. 6

- ^ The White Lion Society: Armorial: Alan Lonsdale Buttifant. Copyright 2019. Accessed 14 March 2019.

- ^ Kenneth Rose, 'Albany: Bishop of London up in Arms', The Sunday Telegraph (29 December 1996)

- ^ The Heraldry Gazette, NS 113 (September 2009), p. 2. [dead link]

- ^ a b D. H. B. Chesshyre, 'Canting Heraldry', The Coat of Arms, no. 139 (Spring 1988). Online edn.

- ^ The Heraldry Gazette, NS 57 (September 1995), p. 6.

- ^ 'Albany at Large', 'Ambassadorial pride of lions', Sunday Telegraph (18 June 1995)

- ^ The Heraldry Gazette, NS 64 (June 1997), p. 6

- ^ The Heraldry Society: Members' Arms: Malcolm Golin. (Accessed 14 June 2017).

- ^ The Heraldry Gazette, NS 51 (March 1994), p. 3

- ^ The Heraldry Gazette, NS 48 (June 1993), p. 6

- ^ Paul Pollak, letter, under 'In Memoriam: Sir Robert Horton (1939–2011)', in OKS Offcuts, Issue 35 (May 2012), p. 8, including a rationale for the design. Archived 11 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The White Lion Society: Armorial: Malcolm Howe. Copyright 2019. Accessed 14 March 2019.

- ^ See also Julian Thorpe, 'Self-styled Peer unveils coat of arms for Bolton village', The Bolton News (29th October 2008). Accessed 14 March 2019

- ^ 'The Armorial Bearings of Brian North Lee F.S.A. of Chiswick', The Seaxe: Newsletter of the Middlesex Heraldry Society, no. 52 (September 2006), p. 9.

- ^ The Heraldry Gazette, NS 109 (September 2008) (scroll to page 4).

- ^ Robert Lampitt, 'College of Arms Visit', Wyre Drawer: Newsletter of the Worshipful Company of Gold and Silver Wyre Drawers, edition 7 (Autumn 2004), pp. 6–7. Archived 17 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Personal staff homepage, Department of Music, University of Nottingham. Updated 12 May 2013. Accessed 23 May 2013. Archived 26 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Heraldry Gazette, NS 56 (June 1995), p. 7

- ^ The Heraldry Gazette, NS 63 (March 1997), p. 6

- ^ The Heraldry Society: Members' Arms: Kenneth Porter. (Accessed 14 June 2017).

- ^ The Heraldry Gazette, NS 70 (December 1998), p. 8

- ^ "Blacktown City Council: Discover Blacktown: Blacktown Memories: Our History & Heritage: Coat of Arms (Accessed 14 June 2017)". Archived from the original on 21 June 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ Heraldry of the World website (Accessed 14 June 2017).

- ^ Laurence Jones, 'Coat of arms of KING'S LYNN AND WEST NORFOLK (England)' (Accessed 14 June 2017).

- ^ The Heraldry Gazette, NS 57 (September 1995), p. 7.

- ^ The Pursuivant, no. 5 (June 1996), i [bound as a supplement to The Heraldry Gazette, NS 60 (June 1996)]

- ^ The Heraldry Gazette, NS 59 (March 1996), p. 5

- ^ a b The Seaxe: Newsletter of the Middlesex Heraldry Society, no. 34 (September 2000), p. 2

- ^ a b The Magazine of Monkton Combe Junior School, 92 (1992–93), p. 2.

- ^ Federation of Family History Societies: Research Tips: Heraldry: FFHS Arms (updated 5 December 2011, accessed 30 August 2012). Includes illustration and rationale.

- ^ Simon Leach, Grant of Supporters 1996, website of The Worshipful Company of Bowyers (June 2013). Accessed 12 March 2014.

- ^ Steven Birks, 'Goodwin Foundry', on thepotteries.org: the local history of Stoke-on-Trent, England. Accessed 11 April 2012.

- ^ Michael Crick, Michael Heseltine: A Biography (London: Penguin, 1997), p. 1.

- ^ Janus: Repositories: Churchill Archives Centre: The Papers of Peter Rawlinson: Personal Papers and Correspondence: Letters and papers concerning PR's life peerage, grant of arms, and genealogy. (Accessed 14 November 2012).

- ^ Steven Gunn and Linda Monckto, eds, Arthur Tudor, Prince of Wales: Life, Death and Commemoration (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2009), pp. 168, 171, colour plate IX).

- ^ The College of Arms Newsletter, no. 10 (September 2006). Accessed 27 January 2012.

- ^ The National Archives: Manuscripts in the Society of Antiquaries of London. Regalia of Queen Elizabeth. "The Restoration of the Regalia to the Tomb of Queen Elizabeth the First in Westminster Abbey: Research into the Identity of the Collar Missing from the Queen's Marble Effigy", by David Hubert Boothby Chesshyre, FSA, Rouge Croix Pursuivant. SAL/MS/852 1973. Paper; ff. 69. 1973. Cloth, red. Presented by Brian Court-Mappin, May 1974. Giftbook entry, 9 May 1974. Accessed 27 October 2011.

- ^ Google Books. Accessed 27 October 2011.

- ^ Donald Buttress, "Restoring the chapel, 1991–6", in Tim Tatton-Brown and Richard Mortimer, eds., Westminster Abbey: The Lady Chapel of Henry VII (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2003), pp. 343ff. (354).

- ^ Susan Matthews, "Stained glass history and technique", The Escutcheon: The Journal of the Cambridge University Heraldic and Genealogical Society, vol. 9, no. 2 (Lent Term 2004), 19–20 (19)[permanent dead link]

- ^ The College of Arms Newsletter December 2005.

- ^ England: Mannesmut und Keuschheit, Der Spiegel 32/1981 (03.08.1981)

- ^ 'Up in arms' and 'And about time too', in The Seaxe: Newsletter of the Middlesex Heraldry Society, no. 7 (September 1995), p. 4.

- ^ John A. Goodall, review, in The Antiquaries Journal, vol. 80, issue 1 (September 2000), 362–3.

- ^ Maurice Keen, review, in Journal of Ecclesiastical History, vol. 52, no. 2 (April 2001), pp. 366–7.

- ^ M. K. Ridgway, review, in The Antiquaries Journal, vol. 59, issue 1 (March 1979), 178.

- ^ Thomas Saunders, Getting a Life: An Autobiography (Bristol: SilverWood Books, 2014), ch. 6.

- ^ Victor E. Neuburg, The Popular Press Companion to Popular Literature (Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1983) p. 34.

- ^ "Research notes of D. H. B. Chesshyre, local historian, re Old Ford Road and neighbourhood", The National Archives website. Accessed 11 April 2012.

- ^ List of Associate Members published in all Bach Choir concert programmes, e.g. Verdi, Requiem and Glazunov Violin Concerto, performed by The Bach Choir and Chetham's Chamber Choir and Symphony Orchestra, conducted by David Hill, at Chester Cathedral on 27 February and at the Royal Festival Hall on 2 March 2010, with an introduction by HRH The Earl of Wessex and notes by Katharine Richman and Molly Cockburn (printed by the Brunswick Press).

- ^ Supplement to the London Gazette 11 June 1988, B4

- ^ The London Gazette Wednesday 31 December 2003 Supplement No. 1, S3.

- ^ The College of Arms Foundation, Activities 2005 Archived 20 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The College of Arms Foundation, Activities 2006 Archived 27 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The College of Arms Foundation, Activities 2007 Archived 10 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The College of Arms Foundation, Activities 2008 Archived 27 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The College of Arms Newsletter 26 (September 2010), p. 2" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ^ a b Table of recipients who have forfeited honours (PDF), Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse, March 2019, retrieved 3 April 2019

- ^ Croft Lyons Committee. Accessed 29 April 2010. Archived 15 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Heraldry Gazette, NS 113 (September 2009), p. 15.

- ^ a b The Heraldry Society: The Society: Fellows and Honorary Fellows. Accessed 4 September 2013.

- ^ S.52, Articles of Association of the Heraldry Society.

- ^ S.3(a), Memorandum of Association of the Heraldry Society.

- ^ The Julian Bickersteth Memorial Medal. Archived 6 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Companies House under 'David Hubert Boothby CHESSHYRE'. Accessed 19 March 2019.

- ^ List of Officers of the Institute.

- ^ a b Doward, Jamie (23 November 2019). "Society of Antiquaries in turmoil after vote to back sex abuser". The Observer. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- ^ Society of Heraldic Arts. Accessed 19 May 2010.Society of Heraldic Arts. Accessed 19 May 2010.

- ^ The White Lion Society: Armorial. Copyright 2019. Accessed 14 March 2019.

- ^ Who's Who, Middlesex Heraldry Society.

- ^ Cambridge University Heraldic and Genealogical Society past events. Archived 5 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ C.U.H.&G.S. – 50th Annual Dinner

- ^ The Daily Telegraph (27 March 2000), p. 22.

- ^ James Lees-Milne, Diaries, 1984–1997, abridged and introduced by Michael Bloch (London: John Murray, 2008), p. 296.

- ^ a b c d e Doward, Jamie (30 March 2019). "Honours system under scrutiny after sex abuser kept title for years". The Observer. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ a b c Public Hearing Transcript 14 March 2019 (PDF), Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse, 14 March 2019, pp. 93–94, retrieved 3 April 2019

- ^ "No. 34532". The London Gazette. 15 July 1938. p. 4651.

- ^ "No. 34535". The London Gazette. 26 July 1938. p. 4856.

- ^ a b c The Seaxe: Newsletter of the Middlesex Heraldry Society, no. 35 (February 2001), p. 4

- ^ T. Machado, Historic Canterbury: St Paul's Church (2007; accessed 18 November 2012).

- ^ The London Gazette (18 August 1840), p. 1903. (Note John Chesshyre's promotion to this rank, which is overlooked in other sources.)

- ^ Cracroft's Peerage. 17 September 2004. Accessed 10 June 2010. Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Huguenot Society of Great Britain & Ireland. Accessed 15 November 2012. Archived 7 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ G.E. Cokayne et al., eds., The Complete Peerage (new edn., 13 vols., 1910–59), i.128; iii.519.

- ^ Samuel Smiles, The Huguenots: Their Settlements, Churches, and Industries, in England and Ireland (6th edn., London: John Murray, 1889), p. 409.

- ^ Charles Mosley, ed., Burke's Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage (107th edn., 3 vols., Wilmington, Delaware: Burke's Peerage (Genealogical Books), 2003), i, 430, quoted in Darryl Lundy's Peerage website.

- ^ Chesshyre and Ailes, Heralds of today 1963–86 (1986), p. 25. See also The Family of Sir Henry Stanley 4th Earl Of Derby and Jane Halsall Archived 8 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Her Majesty's Heralds: A Talk by Our Guest Speaker Hubert Chesshyre, Clarenceux King of Arms, College of Arms (Wynkyn de Worde Society Luncheon|Stationers' Hall|Thursday 19 March 1998; 'Printed at The Cloister Press, Cambridge') [One piece of A4 card, folded once, with the relevant text on the former verso.]

- ^ 'The History of St Mary's', on the website of Halton Parish. Accessed 4 January 2013.

- ^ Chesshyre and Ailes, Heralds of today 1963–86 (1986), p. 26.

- ^ See here for an image of Chesshyre's coat of arms: The Armorial Bearings of the Chester Heralds. Copyright Martin Goldstraw. Accessed 30 April 2010.

- People stripped of a British Commonwealth honour

- English officers of arms

- 1940 births

- Living people

- Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge

- Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford

- People educated at The King's School, Canterbury

- British historians

- Local historians

- British medievalists

- Fellows of the Society of Antiquaries of London

- English folklorists

- English genealogists

- English biographers

- British sex offenders