Executive Order 9066

Executive Order 9066 was a United States presidential executive order signed and issued during World War II by United States president Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942. This order authorized the secretary of war to prescribe certain areas as military zones, clearing the way for the incarceration of Japanese Americans, German Americans, and Italian Americans in U.S. concentration camps.

Transcript of Executive Order 9066

The text of Executive Order 9066 was as follows:[1]

Executive Order No. 9066

The President

Executive Order

Authorizing the Secretary of War to Prescribe Military Areas

Whereas the successful prosecution of the war requires every possible protection against espionage and against sabotage to national-defense material, national-defense premises, and national-defense utilities as defined in Section 4, Act of April 20, 1918, 40 Stat. 533, as amended by the Act of November 30, 1940, 54 Stat. 1220, and the Act of August 21, 1941, 55 Stat. 655 (U.S.C., Title 50, Sec. 104);

Now, therefore, by virtue of the authority vested in me as President of the United States, and Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy, I hereby authorize and direct the Secretary of War, and the Military Commanders whom he may from time to time designate, whenever he or any designated Commander deems such action necessary or desirable, to prescribe military areas in such places and of such extent as he or the appropriate Military Commander may determine, from which any or all persons may be excluded, and with respect to which, the right of any person to enter, remain in, or leave shall be subject to whatever restrictions the Secretary of War or the appropriate Military Commander may impose in his discretion. The Secretary of War is hereby authorized to provide for residents of any such area who are excluded therefrom, such transportation, food, shelter, and other accommodations as may be necessary, in the judgment of the Secretary of War or the said Military Commander, and until other arrangements are made, to accomplish the purpose of this order. The designation of military areas in any region or locality shall supersede designations of prohibited and restricted areas by the Attorney General under the Proclamations of December 7 and 8, 1941, and shall supersede the responsibility and authority of the Attorney General under the said Proclamations in respect of such prohibited and restricted areas.

I hereby further authorize and direct the Secretary of War and the said Military Commanders to take such other steps as he or the appropriate Military Commander may deem advisable to enforce compliance with the restrictions applicable to each Military area here in above authorized to be designated, including the use of Federal troops and other Federal Agencies, with authority to accept assistance of state and local agencies.

I hereby further authorize and direct all Executive Departments, independent establishments and other Federal Agencies, to assist the Secretary of War or the said Military Commanders in carrying out this Executive Order, including the furnishing of medical aid, hospitalization, food, clothing, transportation, use of land, shelter, and other supplies, equipment, utilities, facilities, and services.

This order shall not be construed as modifying or limiting in any way the authority heretofore granted under Executive Order No. 8972, dated December 12, 1941, nor shall it be construed as limiting or modifying the duty and responsibility of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, with respect to the investigation of alleged acts of sabotage or the duty and responsibility of the Attorney General and the Department of Justice under the Proclamations of December 7 and 8, 1941, prescribing regulations for the conduct and control of alien enemies, except as such duty and responsibility is superseded by the designation of military areas hereunder.

Franklin D. Roosevelt

The White House,

February 19, 1942.

Exclusion under the order

On March 21, 1942, Roosevelt signed Public Law 503[2] (approved after only an hour of discussion in the Senate and thirty minutes in the House) in order to provide for the enforcement of his executive order. Authored by War Department official Karl Bendetsen — who would later be promoted to Director of the Wartime Civilian Control Administration and oversee the incarceration of Japanese Americans — the law made violations of military orders a misdemeanor punishable by up to $5,000 in fines and one year in prison.[3]

As a result, approximately 112,000 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry were evicted from the West Coast of the United States and held in American concentration camps and other confinement sites across the country. Japanese Americans in Hawaii were not incarcerated in the same way, despite the attack on Pearl Harbor. Although the Japanese American population in Hawaii was nearly 40% of the population of Hawaii itself, only a few thousand people were detained there, supporting the eventual finding that their mass removal on the West Coast was motivated by reasons other than "military necessity."[4]

Japanese Americans and other Asians in the U.S. had suffered for decades from prejudice and racially-motivated fear. Laws preventing Asian Americans from owning land, voting, testifying against whites in court, and other racially discriminatory laws existed long before World War II. Additionally, the FBI, Office of Naval Intelligence and Military Intelligence Division had been conducting surveillance on Japanese American communities in Hawaii and the continental U.S. from the early 1930s.[5] In early 1941, President Roosevelt secretly commissioned a study to assess the possibility that Japanese Americans would pose a threat to U.S. security. The report, submitted exactly one month before Pearl Harbor was bombed, found that, "There will be no armed uprising of Japanese" in the United States. "For the most part," the Munson Report said, "the local Japanese are loyal to the United States or, at worst, hope that by remaining quiet they can avoid concentration camps or irresponsible mobs."[4] A second investigation started in 1940, written by Naval Intelligence officer Kenneth Ringle and submitted in January 1942, likewise found no evidence of fifth column activity and urged against mass incarceration.[6] Both were ignored.

Over two-thirds of the people of Japanese ethnicity were incarcerated — almost 70,000 — were American citizens. Many of the rest had lived in the country between 20 and 40 years. Most Japanese Americans, particularly the first generation born in the United States (the Nisei), considered themselves loyal to the United States of America. No Japanese American citizen or Japanese national residing in the United States was ever found guilty of sabotage or espionage.[4]

Americans of Italian and German ancestry were also targeted by these restrictions, including internment. 11,000 people of German ancestry were interned, as were 3,000 people of Italian ancestry, along with some Jewish refugees. The interned Jewish refugees came from Germany, as the U.S. government did not differentiate between ethnic Jews and ethnic Germans (the term "Jewish" was defined as a religious practice, not an ethnicity). Some of the internees of European descent were interned only briefly, while others were held for several years beyond the end of the war. Like the Japanese American incarcerees, these smaller groups had American-born citizens in their numbers, especially among the children. A few members of ethnicities of other Axis countries were interned, but exact numbers are unknown.

There were 10 of these concentration camps across the country called “relocation centers”. There were two in Arkansas, two in California, one in Idaho, one in Utah, one in Wyoming, and one in Colorado.[7]

World War II camps under the order

Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson was responsible for assisting relocated people with transport, food, shelter, and other accommodations and delegated Colonel Karl Bendetsen to administer the removal of West Coast Japanese.[1] Over the spring of 1942, Bendetsen issued Western Defense Command orders for Japanese Americans to present themselves for removal. The "evacuees" were taken first to temporary assembly centers, requisitioned fairgrounds and horse racing tracks where living quarters were often converted livestock stalls. As construction on the more permanent and isolated WRA camps was completed, the population was transferred by truck or train. These accommodations consisted of tar paper-walled frame buildings in parts of the country with bitter winters and often hot summers. The camps were guarded by armed soldiers and fenced with barbed wire (security measures not shown in published photographs of the camps). Camps held up to 18,000 people, and were small cities, with medical care, food, and education provided by the government. Adults were offered "camp jobs" with wages of $12 to $19 per month, and many camp services such as medical care and education were provided by the camp inmates themselves.[4]

Suspension and termination

In December 1944, President Roosevelt suspended Executive Order 9066. Incarcerees were released, often to resettlement facilities and temporary housing, and the camps were shut down by 1946.[4]

In the years after the war, the interned Japanese Americans had to rebuild their lives. United States citizens and long-time residents who had been incarcerated lost their personal liberties; many also lost their homes, businesses, property, and savings. Individuals born in Japan were not allowed to become naturalized US citizens until 1952.[4]

On February 19, 1976, President Gerald Ford signed a proclamation formally terminating Executive Order 9066 and apologizing for the internment, stated: "We now know what we should have known then — not only was that evacuation wrong but Japanese-Americans were and are loyal Americans. On the battlefield and at home the names of Japanese-Americans have been and continue to be written in history for the sacrifices and the contributions they have made to the well-being and to the security of this, our common Nation."[8][9] In 1980, President Jimmy Carter signed legislation to create the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC). The CWRIC was appointed to conduct an official governmental study of Executive Order 9066, related wartime orders, and their impact on Japanese Americans in the West and Alaska Natives in the Pribilof Islands.

Apology and redress

In December 1982, the CWRIC issued its findings in Personal Justice Denied, concluding that the incarceration of Japanese Americans had not been justified by military necessity. The report determined that the decision to incarcerate was based on "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership". The Commission recommended legislative remedies consisting of an official Government apology and redress payments of $20,000 to each of the survivors; a public education fund was set up to help ensure that this would not happen again (Pub. L. 100–383). On August 10, 1988, the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, based on the CWRIC recommendations, was signed into law by Ronald Reagan. On November 21, 1989, George H. W. Bush signed an appropriation bill authorizing payments to be paid out between 1990 and 1998. In 1990, surviving internees began to receive individual redress payments and a letter of apology. This bill applied to the Japanese Americans and to members of the Aleut people inhabiting the strategic Aleutian islands in Alaska who were also relocated.[10]

Legacy

February 19th, the anniversary of the signing of Executive Order 9066, is now the Day of Remembrance, an annual commemoration of the unjust incarceration of the Japanese-American community.[11]

In 2017, the Smithsonian launched an exhibit that contextualizes the document with artwork by Roger Shimomura.[12]

See also

- Fred Korematsu Day

- Executive Order 9102

- War Relocation Authority

- Hirabayashi v. United States

- Korematsu v. United States

- Ex parte Endo

- Defence Regulation 18B

- Manzanar

- Japanese American service in World War II

References

- ^ a b Roosevelt, Franklin (February 19, 1942). "Executive Order 9066". U.S. National Archives & Records Administration. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ^ AN ACT To provide a penalty for violation of restriction or orders with respect to persons entering, remaining in, leaving, or committing any act in military areas or zones. Pub. L. 77–503, 56 Stat. 173, enacted March 21, 1942

- ^ Niiya, Brian. "Public Law 503". Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 20, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f "Relocation and Incarceration of Japanese Americans During World War II". University of California – Japanese American Relocation Digital Archives. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ^ Kashima, Tetsuden. "Custodial detention / A-B-C list". Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 20, 2014.

- ^ Niiya, Brian. "Kenneth Ringle". Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 20, 2014.

- ^ "Japanese Relocation During World War II". National Archives. August 15, 2016. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ President Gerald R. Ford's Proclamation 4417.

- ^ "President Gerald R. Ford's Remarks Upon Signing a Proclamation Concerning Japanese-American Internment During World War II". Ford Library Museum. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ US Government (August 10, 1988). "Public Law 100-383 – The Civil Liberties Act of 1988". Topaz Japanese-American Relocation Center Digital Collection. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ^ "Day of Remembrance for Japanese-Americans Interned During WWII". Long Beach Post.

- ^ https://www.si.edu/sisearch/search-exhibitions?edan_q=Righting%2Ba%2BWrong

External links

- Text of Executive Order No. 9066

- Digital Copy of Signed Executive Order No. 9066

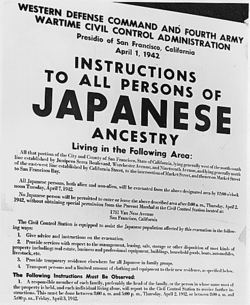

- Instructional poster for San Francisco

- Instructional poster for Los Angeles

- German American Internment Coalition

- FOITimes a resource for European American Internment of World War 2

- "The War Relocation Centers of World War II: When Fear Was Stronger than Justice", a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- JapaneseRelocation.org searchable data for over 100,000 Japanese Americans Interned at camps