Coriolis force

In physics, the Coriolis force is an inertial or fictitious force[1] that seems to act on objects that are in motion within a frame of reference that rotates with respect to an inertial frame. In a reference frame with clockwise rotation, the force acts to the left of the motion of the object. In one with anticlockwise (or counterclockwise) rotation, the force acts to the right. Deflection of an object due to the Coriolis force is called the Coriolis effect. Though recognized previously by others, the mathematical expression for the Coriolis force appeared in an 1835 paper by French scientist Gaspard-Gustave de Coriolis, in connection with the theory of water wheels. Early in the 20th century, the term Coriolis force began to be used in connection with meteorology.

Newton's laws of motion describe the motion of an object in an inertial (non-accelerating) frame of reference. When Newton's laws are transformed to a rotating frame of reference, the Coriolis force and centrifugal force appear. Both forces are proportional to the mass of the object. The Coriolis force is proportional to the rotation rate and the centrifugal force is proportional to the square of the rotation rate. The Coriolis force acts in a direction perpendicular to the rotation axis and to the velocity of the body in the rotating frame and is proportional to the object's speed in the rotating frame (more precisely, to the component of its velocity that is perpendicular to the axis of rotation). The centrifugal force acts outwards in the radial direction and is proportional to the distance of the body from the axis of the rotating frame. These additional forces are termed inertial forces, fictitious forces or pseudo forces.[2] They allow the application of Newton's laws to a rotating system. They are correction factors that do not exist in a non-accelerating or inertial reference frame.

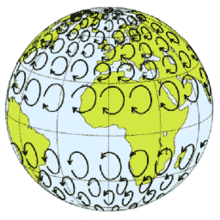

In popular (non-technical) usage of the term "Coriolis effect", the rotating reference frame implied is almost always the Earth. Because the Earth spins, Earth-bound observers need to account for the Coriolis force to correctly analyze the motion of objects. The Earth completes one rotation per day, so for motions of everyday objects the Coriolis force is usually quite small compared to other forces; its effects generally become noticeable only for motions occurring over large distances and long periods of time, such as large-scale movement of air in the atmosphere or water in the ocean. Such motions are constrained by the surface of the Earth, so only the horizontal component of the Coriolis force is generally important. This force causes moving objects on the surface of the Earth to be deflected to the right (with respect to the direction of travel) in the Northern Hemisphere and to the left in the Southern Hemisphere. The horizontal deflection effect is greater near the poles, since the effective rotation rate about a local vertical axis is largest there, and decreases to zero at the equator.[3] Rather than flowing directly from areas of high pressure to low pressure, as they would in a non-rotating system, winds and currents tend to flow to the right of this direction north of the equator and to the left of this direction south of it. This effect is responsible for the rotation of large cyclones (see Coriolis effects in meteorology).

For an intuitive explanation of the origin of the Coriolis force, consider an object, constrained to follow the Earth's surface and moving northward in the northern hemisphere. Viewed from outer space, the object does not appear to go to north, but has an eastward motion (it rotates around toward the right along with the surface of the Earth). The further north you go, the smaller the "diameter of its parallel" (the minimum distance from the surface point to the axis of rotation, which is in a plane orthogonal to the axis), and so the slower the eastward motion of its surface. As the object moves north, to higher latitudes, it has a tendency to maintain the eastward speed it started with (rather than slowing down to match the reduced eastward speed of local objects on the Earth's surface), so it veers east (i.e. to the right of its initial motion).[4][5]

Though not obvious from this example, which considers northward motion, the horizontal deflection occurs equally for objects moving east or west (or any other direction).[6]

History

Italian scientist Giovanni Battista Riccioli and his assistant Francesco Maria Grimaldi described the effect in connection with artillery in the 1651 Almagestum Novum, writing that rotation of the Earth should cause a cannonball fired to the north to deflect to the east.[7] In 1674 Claude François Milliet Dechales described in his Cursus seu Mundus Mathematicus how the rotation of the Earth should cause a deflection in the trajectories of both falling bodies and projectiles aimed toward one of the planet's poles. Riccioli, Grimaldi, and Dechales all described the effect as part of an argument against the heliocentric system of Copernicus. In other words, they argued that the Earth's rotation should create the effect, and so failure to detect the effect was evidence for an immobile Earth.[8] The Coriolis acceleration equation was derived by Euler in 1749[9][10] and the effect was described in the tidal equations of Pierre-Simon Laplace in 1778.[11]

Gaspard-Gustave Coriolis published a paper in 1835 on the energy yield of machines with rotating parts, such as waterwheels.[12] That paper considered the supplementary forces that are detected in a rotating frame of reference. Coriolis divided these supplementary forces into two categories. The second category contained a force that arises from the cross product of the angular velocity of a coordinate system and the projection of a particle's velocity into a plane perpendicular to the system's axis of rotation. Coriolis referred to this force as the "compound centrifugal force" due to its analogies with the centrifugal force already considered in category one.[13][14] The effect was known in the early 20th century as the "acceleration of Coriolis",[15] and by 1920 as "Coriolis force".[16]

In 1856, William Ferrel proposed the existence of a circulation cell in the mid-latitudes with air being deflected by the Coriolis force to create the prevailing westerly winds.[17]

The understanding of the kinematics of how exactly the rotation of the Earth affects airflow was partial at first.[18] Late in the 19th century, the full extent of the large scale interaction of pressure-gradient force and deflecting force that in the end causes air masses to move along isobars was understood.[19]

Formula

In Newtonian mechanics, the equation of motion for an object in an inertial reference frame is

where is the vector sum of the physical forces acting on the object, is the mass of the object, and is the acceleration of the object relative to the inertial reference frame.

Transforming this equation to a reference frame about a fixed axis through the origin with rotation vector having variable rotation rate, the equation takes the form

where

- is the rotation vector, with magnitude , of the rotating reference frame relative to the inertial frame

- is the vector sum of the physical forces acting on the object relative to the rotating reference frame

- is the velocity relative to the rotating reference frame

- is the position vector of the object relative to the rotating reference frame

- is the acceleration relative to the rotating reference frame

The fictitious forces as they are perceived in the rotating frame as additional forces that contribute to the apparent acceleration just like the real external forces.[20][21] The fictitious force terms of the equation are, reading from left to right:[22]

- Euler force

- Coriolis force

- centrifugal force

Notice the Euler and centrifugal forces depend on the position vector of the object, while the Coriolis force depends on the object's velocity as measured in the rotating reference frame. As expected, for a non-rotating inertial frame of reference the Coriolis force and all other fictitious forces disappear.[23] The forces also disappear for zero mass .

As the Coriolis force is proportional to a cross product of two vectors, it is perpendicular to both vectors, in this case the object's velocity and the frame's rotation vector. It therefore follows that:

- if the velocity is parallel to the rotation axis, the Coriolis force is zero. (For example, on Earth, this situation occurs for a body on the equator moving north or south relative to Earth's surface.)

- if the velocity is straight inward to the axis, the Coriolis force is in the direction of local rotation. (For example, on Earth, this situation occurs for a body on the equator falling downward, as in the Dechales illustration above, where the falling ball travels further to the east than does the tower.)

- if the velocity is straight outward from the axis, the Coriolis force is against the direction of local rotation. (In the tower example, a ball launched upward would move toward the west.)

- if the velocity is in the direction of rotation, the Coriolis force is outward from the axis. (For example, on Earth, this situation occurs for a body on the equator moving east relative to Earth's surface. It would move upward as seen by an observer on the surface. This effect (see Eötvös effect below) was discussed by Galileo Galilei in 1632 and by Riccioli in 1651.[24])

- if the velocity is against the direction of rotation, the Coriolis force is inward to the axis. (On Earth, this situation occurs for a body on the equator moving west, which would deflect downward as seen by an observer.)

Causes

The Coriolis force exists only when one uses a rotating reference frame. In the rotating frame it behaves exactly like a real force (that is to say, it causes acceleration and has real effects). However, the Coriolis force is a consequence of inertia,[25] and is not attributable to an identifiable originating body, as is the case for electromagnetic or nuclear forces, for example. From an analytical viewpoint, to use Newton's second law in a rotating system, the Coriolis force is mathematically necessary, but it disappears in a non-accelerating, inertial frame of reference. For example, consider two children on opposite sides of a spinning roundabout (Merry-go-round), who are throwing a ball to each other. From the children's point of view, this ball's path is curved sideways by the Coriolis force. Suppose the roundabout spins anticlockwise when viewed from above. From the thrower's perspective, the deflection is to the right.[26] From the non-thrower's perspective, deflection is to the left (for a mathematical formulation see Mathematical derivation of fictitious forces). In meteorology, a rotating frame (the Earth) with its Coriolis force provides a more natural framework for explanation of air movements than a non-rotating inertial frame without Coriolis forces.[27] In long-range gunnery, sight corrections for the Earth's rotation are based on the Coriolis force.[28] These examples are described in more detail below.

The acceleration entering the Coriolis force arises from two sources of change in velocity that result from rotation: the first is the change of the velocity of an object in time. The same velocity (in an inertial frame of reference where the normal laws of physics apply) is seen as different velocities at different times in a rotating frame of reference. The apparent acceleration is proportional to the angular velocity of the reference frame (the rate at which the coordinate axes change direction), and to the component of velocity of the object in a plane perpendicular to the axis of rotation. This gives a term . The minus sign arises from the traditional definition of the cross product (right-hand rule), and from the sign convention for angular velocity vectors.

The second is the change of velocity in space. Different positions in a rotating frame of reference have different velocities (as seen from an inertial frame of reference). For an object to move in a straight line, it must accelerate so that its velocity changes from point to point by the same amount as the velocities of the frame of reference. The force is proportional to the angular velocity (which determines the relative speed of two different points in the rotating frame of reference), and to the component of the velocity of the object in a plane perpendicular to the axis of rotation (which determines how quickly it moves between those points). This also gives a term .

Length scales and the Rossby number

The time, space and velocity scales are important in determining the importance of the Coriolis force. Whether rotation is important in a system can be determined by its Rossby number, which is the ratio of the velocity, U, of a system to the product of the Coriolis parameter,, and the length scale, L, of the motion:

The Rossby number is the ratio of inertial to Coriolis forces. A small Rossby number indicates a system is strongly affected by Coriolis forces, and a large Rossby number indicates a system in which inertial forces dominate. For example, in tornadoes, the Rossby number is large, in low-pressure systems it is low, and in oceanic systems it is around 1. As a result, in tornadoes the Coriolis force is negligible, and balance is between pressure and centrifugal forces. In low-pressure systems, centrifugal force is negligible and balance is between Coriolis and pressure forces. In the oceans all three forces are comparable.[29]

An atmospheric system moving at U = 10 m/s (22 mph) occupying a spatial distance of L = 1,000 km (621 mi), has a Rossby number of approximately 0.1.

A baseball pitcher may throw the ball at U = 45 m/s (100 mph) for a distance of L = 18.3 m (60 ft). The Rossby number in this case would be 32,000.

Baseball players don't care about which hemisphere they're playing in. However, an unguided missile obeys exactly the same physics as a baseball, but can travel far enough and be in the air long enough to experience the effect of Coriolis force. Long-range shells in the Northern Hemisphere landed close to, but to the right of, where they were aimed until this was noted. (Those fired in the Southern Hemisphere landed to the left.) In fact, it was this effect that first got the attention of Coriolis himself.[30][31][32]

Simple cases

This section may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (March 2014) |

Cannon on turntable

This section may be too technical for most readers to understand. (June 2010) |

The animation at the top of this article is a classic illustration of Coriolis force. Another visualization of the Coriolis and centrifugal forces is this animation clip.

Given the radius R of the turntable in that animation, the rate of angular rotation ω, and the speed of the cannonball (assumed constant) v, the correct angle θ to aim so as to hit the target at the edge of the turntable can be calculated.

The inertial frame of reference provides one way to handle the question: calculate the time to interception, which is tf = R / v . Then, the turntable revolves an angle ω tf in this time. If the cannon is pointed an angle θ = ω tf = ω R / v, then the cannonball arrives at the periphery at position number 3 at the same time as the target.

No discussion of Coriolis force can arrive at this solution as simply, so the reason to treat this problem is to demonstrate Coriolis formalism in an easily visualized situation.

Trajectory in the inertial frame

The trajectory in the inertial frame (denoted A) is a straight line radial path at angle θ. The position of the cannonball in (x, y) coordinates at time t is:

In the turntable frame (denoted B), the x- y axes rotate at angular rate ω, so the trajectory becomes:

and three examples of this result are plotted in the figure.

Accelerations

Components of acceleration

To determine the components of acceleration, a general expression is used from the article fictitious force:

in which the term in Ω × vB is the Coriolis acceleration and the term in Ω × (Ω × rB) is the centrifugal acceleration. The results are (let α = θ − ωt):

Producing accelerations

Producing a centrifugal acceleration:

Also:

producing a Coriolis acceleration:

These accelerations are shown in the diagrams for a particular example.

It is seen that the Coriolis acceleration not only cancels the centrifugal acceleration, but together they provide a net "centripetal", radially inward component of acceleration (that is, directed toward the center of rotation):[33]

and an additional component of acceleration perpendicular to rB(t):

The "centripetal" component of acceleration resembles that for circular motion at radius rB, while the perpendicular component is velocity dependent, increasing with the radial velocity v and directed to the right of the velocity. The situation could be described as a circular motion combined with an "apparent Coriolis acceleration" of 2ωv. However, this is a rough labelling: a careful designation of the true centripetal force refers to a local reference frame that employs the directions normal and tangential to the path, not coordinates referred to the axis of rotation.

These results also can be obtained directly by two time differentiations of rB(t). Agreement of the two approaches demonstrates that one could start from the general expression for fictitious acceleration above and derive the trajectories shown here. However, working from the acceleration to the trajectory is more complicated than the reverse procedure used here, which is made possible in this example by knowing the answer in advance.

As a result of this analysis an important point appears: all the fictitious accelerations must be included to obtain the correct trajectory. In particular, besides the Coriolis acceleration, the centrifugal force plays an essential role. It is easy to get the impression from verbal discussions of the cannonball problem, which focus on displaying the Coriolis effect particularly, that the Coriolis force is the only factor that must be considered,[34] but that is not so.[35] A turntable for which the Coriolis force is the only factor is the parabolic turntable. A somewhat more complex situation is the idealized example of flight routes over long distances, where the centrifugal force of the path and aeronautical lift are countered by gravitational attraction.[36][37]

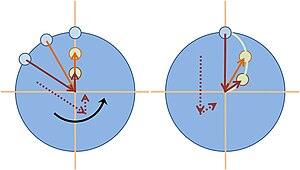

Tossed ball on a rotating carousel

The figure illustrates a ball tossed from 12:00 o'clock toward the center of a counter-clockwise rotating carousel. On the left, the ball is seen by a stationary observer above the carousel, and the ball travels in a straight line to the center, while the ball-thrower rotates counter-clockwise with the carousel. On the right the ball is seen by an observer rotating with the carousel, so the ball-thrower appears to stay at 12:00 o'clock. The figure shows how the trajectory of the ball as seen by the rotating observer can be constructed.

On the left, two arrows locate the ball relative to the ball-thrower. One of these arrows is from the thrower to the center of the carousel (providing the ball-thrower's line of sight), and the other points from the center of the carousel to the ball. (This arrow gets shorter as the ball approaches the center.) A shifted version of the two arrows is shown dotted.

On the right is shown this same dotted pair of arrows, but now the pair are rigidly rotated so the arrow corresponding to the line of sight of the ball-thrower toward the center of the carousel is aligned with 12:00 o'clock. The other arrow of the pair locates the ball relative to the center of the carousel, providing the position of the ball as seen by the rotating observer. By following this procedure for several positions, the trajectory in the rotating frame of reference is established as shown by the curved path in the right-hand panel.

The ball travels in the air, and there is no net force upon it. To the stationary observer the ball follows a straight-line path, so there is no problem squaring this trajectory with zero net force. However, the rotating observer sees a curved path. Kinematics insists that a force (pushing to the right of the instantaneous direction of travel for a counter-clockwise rotation) must be present to cause this curvature, so the rotating observer is forced to invoke a combination of centrifugal and Coriolis forces to provide the net force required to cause the curved trajectory.

Bounced ball

The figure describes a more complex situation where the tossed ball on a turntable bounces off the edge of the carousel and then returns to the tosser, who catches the ball. The effect of Coriolis force on its trajectory is shown again as seen by two observers: an observer (referred to as the "camera") that rotates with the carousel, and an inertial observer. The figure shows a bird's-eye view based upon the same ball speed on forward and return paths. Within each circle, plotted dots show the same time points. In the left panel, from the camera's viewpoint at the center of rotation, the tosser (smiley face) and the rail both are at fixed locations, and the ball makes a very considerable arc on its travel toward the rail, and takes a more direct route on the way back. From the ball tosser's viewpoint, the ball seems to return more quickly than it went (because the tosser is rotating toward the ball on the return flight).

On the carousel, instead of tossing the ball straight at a rail to bounce back, the tosser must throw the ball toward the right of the target and the ball then seems to the camera to bear continuously to the left of its direction of travel to hit the rail (left because the carousel is turning clockwise). The ball appears to bear to the left from direction of travel on both inward and return trajectories. The curved path demands this observer to recognize a leftward net force on the ball. (This force is "fictitious" because it disappears for a stationary observer, as is discussed shortly.) For some angles of launch, a path has portions where the trajectory is approximately radial, and Coriolis force is primarily responsible for the apparent deflection of the ball (centrifugal force is radial from the center of rotation, and causes little deflection on these segments). When a path curves away from radial, however, centrifugal force contributes significantly to deflection.

The ball's path through the air is straight when viewed by observers standing on the ground (right panel). In the right panel (stationary observer), the ball tosser (smiley face) is at 12 o'clock and the rail the ball bounces from is at position one (1). From the inertial viewer's standpoint, positions one (1), two (2), three (3) are occupied in sequence. At position 2 the ball strikes the rail, and at position 3 the ball returns to the tosser. Straight-line paths are followed because the ball is in free flight, so this observer requires that no net force is applied.

Applied to the Earth

The concept "Coriolis force" is specially suitable for the description of motion of atmosphere (i.e. winds) over the surface of the Earth. The Earth (like all rotating celestial bodies) has taken the shape of an oblate spheroid, such that the gravitational force is slightly off-set towards the Earth axis as illustrated in the figure.

For a mass point at rest on the Earth surface the horizontal component of the gravitation counteracts the "centrifugal force" preventing it to slide away towards the equator. This means that the vector term of the "equation of motion" above

is directed straight down, orthogonal to the surface of the Earth. The force affecting the motion of air "sliding" over the Earth surface is therefore (only) the horizontal component of the Coriolis term

This component is orthogonal to the velocity over the Earth surface and is given by the expression

where

- is the spin rate of the Earth

- is the latitude, positive in northern hemisphere and negative in the southern hemisphere

In the northern hemisphere where the sign is positive this force/acceleration, as viewed from above, is to the right of the direction of motion, in the southern hemisphere where the sign is negative this force/acceleration is to the left of the direction of motion

Intuitive explanation

As the Earth turns around its axis, everything attached to it, including the atmosphere, turns with it (imperceptibly to our senses). An object that is moving without being dragged along with the surface rotation or atmosphere such as an object in ballistic flight or an independent air mass within the atmosphere, travels in a straight motion over the turning Earth. From our rotating perspective on the planet, the direction of motion of an object in ballistic flight changes as it moves, bending in the opposite direction to our actual motion.

When viewed from a stationary point in space directly above the north pole, any land feature in the Northern Hemisphere turns anticlockwise—and, fixing our gaze on that location, any other location in that hemisphere rotates around it the same way. The traced ground path of a freely moving body in ballistic flight traveling from one point to another therefore bends the opposite way, clockwise, which is conventionally labeled as "right," where it will be if the direction of motion is considered "ahead," and "down" is defined naturally.

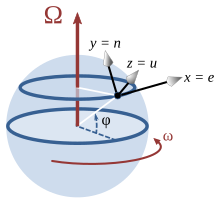

Rotating sphere

Consider a location with latitude φ on a sphere that is rotating around the north-south axis.[38] A local coordinate system is set up with the x axis horizontally due east, the y axis horizontally due north and the z axis vertically upwards. The rotation vector, velocity of movement and Coriolis acceleration expressed in this local coordinate system (listing components in the order east (e), north (n) and upward (u)) are:

When considering atmospheric or oceanic dynamics, the vertical velocity is small, and the vertical component of the Coriolis acceleration is small compared to gravity. For such cases, only the horizontal (east and north) components matter. The restriction of the above to the horizontal plane is (setting vu = 0):

where is called the Coriolis parameter.

By setting vn = 0, it can be seen immediately that (for positive φ and ω) a movement due east results in an acceleration due south. Similarly, setting ve = 0, it is seen that a movement due north results in an acceleration due east. In general, observed horizontally, looking along the direction of the movement causing the acceleration, the acceleration always is turned 90° to the right and of the same size regardless of the horizontal orientation.

As a different case, consider equatorial motion setting φ = 0°. In this case, Ω is parallel to the north or n-axis, and:

Accordingly, an eastward motion (that is, in the same direction as the rotation of the sphere) provides an upward acceleration known as the Eötvös effect, and an upward motion produces an acceleration due west.

Meteorology

Perhaps the most important impact of the Coriolis effect is in the large-scale dynamics of the oceans and the atmosphere. In meteorology and oceanography, it is convenient to postulate a rotating frame of reference wherein the Earth is stationary. In accommodation of that provisional postulation, the centrifugal and Coriolis forces are introduced. Their relative importance is determined by the applicable Rossby numbers. Tornadoes have high Rossby numbers, so, while tornado-associated centrifugal forces are quite substantial, Coriolis forces associated with tornadoes are for practical purposes negligible.[39]

Because surface ocean currents are driven by the movement of wind over the water's surface, the Coriolis force also affects the movement of ocean currents and cyclones as well. Many of the ocean's largest currents circulate around warm, high-pressure areas called gyres. Though the circulation is not as significant as that in the air, the deflection caused by the Coriolis effect is what creates the spiraling pattern in these gyres. The spiraling wind pattern helps the hurricane form. The stronger the force from the Coriolis effect, the faster the wind spins and picks up additional energy, increasing the strength of the hurricane.[40]

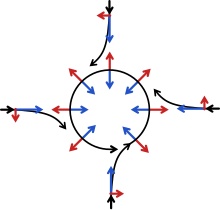

Air within high-pressure systems rotates in a direction such that the Coriolis force is directed radially inwards, and nearly balanced by the outwardly radial pressure gradient. As a result, air travels clockwise around high pressure in the Northern Hemisphere and anticlockwise in the Southern Hemisphere. Air around low-pressure rotates in the opposite direction, so that the Coriolis force is directed radially outward and nearly balances an inwardly radial pressure gradient.[41][citation needed]

Flow around a low-pressure area

If a low-pressure area forms in the atmosphere, air tends to flow in towards it, but is deflected perpendicular to its velocity by the Coriolis force. A system of equilibrium can then establish itself creating circular movement, or a cyclonic flow. Because the Rossby number is low, the force balance is largely between the pressure-gradient force acting towards the low-pressure area and the Coriolis force acting away from the center of the low pressure.

Instead of flowing down the gradient, large scale motions in the atmosphere and ocean tend to occur perpendicular to the pressure gradient. This is known as geostrophic flow.[42] On a non-rotating planet, fluid would flow along the straightest possible line, quickly eliminating pressure gradients. Note that the geostrophic balance is thus very different from the case of "inertial motions" (see below), which explains why mid-latitude cyclones are larger by an order of magnitude than inertial circle flow would be.

This pattern of deflection, and the direction of movement, is called Buys-Ballot's law. In the atmosphere, the pattern of flow is called a cyclone. In the Northern Hemisphere the direction of movement around a low-pressure area is anticlockwise. In the Southern Hemisphere, the direction of movement is clockwise because the rotational dynamics is a mirror image there.[43] At high altitudes, outward-spreading air rotates in the opposite direction.[44] Cyclones rarely form along the equator due to the weak Coriolis effect present in this region.[45]

Inertial circles

An air or water mass moving with speed subject only to the Coriolis force travels in a circular trajectory called an 'inertial circle'. Since the force is directed at right angles to the motion of the particle, it moves with a constant speed around a circle whose radius is given by:

where is the Coriolis parameter , introduced above (where is the latitude). The time taken for the mass to complete a full circle is therefore . The Coriolis parameter typically has a mid-latitude value of about 10−4 s−1; hence for a typical atmospheric speed of 10 m/s (22 mph) the radius is 100 km (62 mi), with a period of about 17 hours. For an ocean current with a typical speed of 10 cm/s (0.22 mph), the radius of an inertial circle is 1 km (0.6 mi). These inertial circles are clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere (where trajectories are bent to the right) and anticlockwise in the Southern Hemisphere.

If the rotating system is a parabolic turntable, then is constant and the trajectories are exact circles. On a rotating planet, varies with latitude and the paths of particles do not form exact circles. Since the parameter varies as the sine of the latitude, the radius of the oscillations associated with a given speed are smallest at the poles (latitude = ±90°), and increase toward the equator.[46]

Other terrestrial effects

The Coriolis effect strongly affects the large-scale oceanic and atmospheric circulation, leading to the formation of robust features like jet streams and western boundary currents. Such features are in geostrophic balance, meaning that the Coriolis and pressure gradient forces balance each other. Coriolis acceleration is also responsible for the propagation of many types of waves in the ocean and atmosphere, including Rossby waves and Kelvin waves. It is also instrumental in the so-called Ekman dynamics in the ocean, and in the establishment of the large-scale ocean flow pattern called the Sverdrup balance.

Eötvös effect

The practical impact of the "Coriolis effect" is mostly caused by the horizontal acceleration component produced by horizontal motion.

There are other components of the Coriolis effect. Westward-travelling objects are deflected downwards (feel heavier), while Eastward-travelling objects are deflected upwards (feel lighter).[47] This is known as the Eötvös effect. This aspect of the Coriolis effect is greatest near the equator. The force produced by this effect is similar to the horizontal component, but the much larger vertical forces due to gravity and pressure mean that it is generally unimportant dynamically.

In addition, objects travelling upwards (i.e., out) or downwards (i.e., in) are deflected to the west or east respectively. This effect is also the greatest near the equator. Since vertical movement is usually of limited extent and duration, the size of the effect is smaller and requires precise instruments to detect. However, in the case of large changes of momentum, such as a spacecraft being launched into orbit, the effect becomes significant. The fastest and most fuel-efficient path to orbit is a launch from the equator that curves to a directly eastward heading.

Intuitive example

Imagine a train that travels through a frictionless railway line along the equator. Assume that, when in motion, it moves at the necessary speed to complete a trip around the world in one day (465 m/s).[48] The Coriolis effect can be considered in three cases: when the train travels west, when it is at rest, and when it travels east. In each case, the Coriolis effect can be calculated from the rotating frame of reference on Earth first, and then checked against a fixed inertial frame. The image below illustrates the three cases as viewed by an observer at rest in a (near) inertial frame from a fixed point above the North Pole along the Earth's axis of rotation; the train is denoted by a few red pixels, fixed at the left side in the leftmost picture, moving in the others

- 1. The train travels toward the west: In that case, it moves against the direction of rotation. Therefore, on the Earth's rotating frame the Coriolis term is pointed inwards towards the axis of rotation (down). This additional force downwards should cause the train to be heavier while moving in that direction.

- If one looks at this train from the fixed non-rotating frame on top of the center of the Earth, at that speed it remains stationary as the Earth spins beneath it. Hence, the only force acting on it is gravity and the reaction from the track. This force is greater (by 0.34%)[48] than the force that the passengers and the train experience when at rest (rotating along with Earth). This difference is what the Coriolis effect accounts for in the rotating frame of reference.

- 2. The train comes to a stop: From the point of view on the Earth's rotating frame, the velocity of the train is zero, thus the Coriolis force is also zero and the train and its passengers recuperate their usual weight.

- From the fixed inertial frame of reference above Earth, the train now rotates along with the rest of the Earth. 0.34% of the force of gravity provides the centripetal force needed to achieve the circular motion on that frame of reference. The remaining force, as measured by a scale, makes the train and passengers "lighter" than in the previous case.

- 3. The train travels east. In this case, because it moves in the direction of Earth's rotating frame, the Coriolis term is directed outward from the axis of rotation (up). This upward force makes the train seem lighter still than when at rest.

- From the fixed inertial frame of reference above Earth, the train travelling east now rotates at twice the rate as when it was at rest—so the amount of centripetal force needed to cause that circular path increases leaving less force from gravity to act on the track. This is what the Coriolis term accounts for on the previous paragraph.

- As a final check one can imagine a frame of reference rotating along with the train. Such frame would be rotating at twice the angular velocity as Earth's rotating frame. The resulting centrifugal force component for that imaginary frame would be greater. Since the train and its passengers are at rest, that would be the only component in that frame explaining again why the train and the passengers are lighter than in the previous two cases.

This also explains why high speed projectiles that travel west are deflected down, and those that travel east are deflected up. This vertical component of the Coriolis effect is called the Eötvös effect.[49]

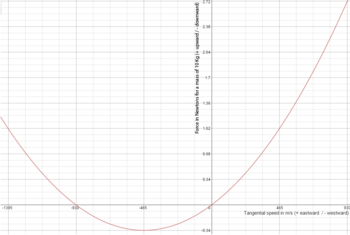

The above example can be used to explain why the Eötvös effect starts diminishing when an object is travelling westward as its tangential speed increases above Earth's rotation (465 m/s). If the westward train in the above example increases speed, part of the force of gravity that pushes against the track accounts for the centripetal force needed to keep it in circular motion on the inertial frame. Once the train doubles its westward speed at 930 m/s that centripetal force becomes equal to the force the train experiences when it stops. From the inertial frame, in both cases it rotates at the same speed but in the opposite directions. Thus, the force is the same cancelling completely the Eötvös effect. Any object that moves westward at a speed above 930 m/s experiences an upward force instead. In the figure, the Eötvös effect is illustrated for a 10 kilogram object on the train at different speeds. The parabolic shape is because the centripetal force is proportional to the square of the tangential speed. On the inertial frame, the bottom of the parabola is centered at the origin. The offset is because this argument uses the Earth's rotating frame of reference. The graph shows that the Eötvös effect is not symmetrical, and that the resulting downward force experienced by an object that travels west at high velocity is less than the resulting upward force when it travels east at the same speed.

Draining in bathtubs and toilets

Contrary to popular misconception, water rotation in home bathrooms under normal circumstances is not related to the Coriolis effect or to the rotation of the Earth, and no consistent difference in rotation direction between toilet drainage in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres can be observed.[50][51][52][53] The formation of a vortex over the plug hole may be explained by the conservation of angular momentum: The radius of rotation decreases as water approaches the plug hole, so the rate of rotation increases, for the same reason that an ice skater's rate of spin increases as they pull their arms in. Any rotation around the plug hole that is initially present accelerates as water moves inward.

The Coriolis force still affects the direction of the flow of water, but only minutely. Only if the water is so still that the effective rotation rate of the Earth is faster than that of the water relative to its container, and if externally applied torques (such as might be caused by flow over an uneven bottom surface) are small enough, the Coriolis effect may indeed determine the direction of the vortex. Without such careful preparation, the Coriolis effect is likely to be much smaller than various other influences on drain direction[54] such as any residual rotation of the water[55] and the geometry of the container.[56] Despite this, the idea that toilets and bathtubs drain differently in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres has been popularized by several television programs and films, including Escape Plan, Wedding Crashers, The Simpsons episode "Bart vs. Australia", Pole to Pole,[57][58] and The X-Files episode "Die Hand Die Verletzt".[59] Several science broadcasts and publications, including at least one college-level physics textbook, have also stated this.[60][61]

In 1908, the Austrian physicist Ottokar Tumlirz described careful and effective experiments that demonstrated the effect of the rotation of the Earth on the outflow of water through a central aperture.[62] The subject was later popularized in a famous 1962 article in the journal Nature, which described an experiment in which all other forces to the system were removed by filling a 6 ft (1.8 m) tank with 300 U.S. gal (1,100 L) of water and allowing it to settle for 24 hours (to allow any movement due to filling the tank to die away), in a room where the temperature had stabilized. The drain plug was then very slowly removed, and tiny pieces of floating wood were used to observe rotation. During the first 12 to 15 minutes, no rotation was observed. Then, a vortex appeared and consistently began to rotate in an anticlockwise direction (the experiment was performed in Boston, Massachusetts, in the Northern Hemisphere). This was repeated and the results averaged to make sure the effect was real. The report noted that the vortex rotated, "about 30,000 times faster than the effective rotation of the Earth in 42° North (the experiment's location)". This shows that the small initial rotation due to the Earth is amplified by gravitational draining and conservation of angular momentum to become a rapid vortex and may be observed under carefully controlled laboratory conditions.[63][64]

Ballistic trajectories

The Coriolis force is important in external ballistics for calculating the trajectories of very long-range artillery shells. The most famous historical example was the Paris gun, used by the Germans during World War I to bombard Paris from a range of about 120 km (75 mi). The Coriolis force minutely changes the trajectory of a bullet, affecting accuracy at extremely long distances. It is adjusted for by accurate long-distance shooters, such as snipers. At the latitude of Sacramento a 1000-yard shot would be deflected 3 inches to the right. There is also a vertical component, explained in the Eötvös effect section above, which causes westward shots to hit low, and eastward shots to hit high.[28][65]

The effects of the Coriolis force on ballistic trajectories should not be confused with the curvature of the paths of missiles, satellites, and similar objects when the paths are plotted on two-dimensional (flat) maps, such as the Mercator projection. The projections of the three-dimensional curved surface of the Earth to a two-dimensional surface (the map) necessarily results in distorted features. The apparent curvature of the path is a consequence of the sphericity of the Earth and would occur even in a non-rotating frame.[citation needed]

Visualization of the Coriolis effect

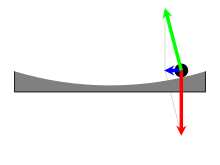

Left: The inertial point of view.

Right: The co-rotating point of view.

Red: gravity

Green: the normal force

Blue: the net resultant centripetal force.

To demonstrate the Coriolis effect, a parabolic turntable can be used. On a flat turntable, the inertia of a co-rotating object forces it off the edge. However, if the turntable surface has the correct paraboloid (parabolic bowl) shape (see the figure) and rotates at the corresponding rate, the force components shown in the figure make the component of gravity tangential to the bowl surface exactly equal to the centripetal force necessary to keep the object rotating at its velocity and radius of curvature (assuming no friction). (See banked turn.) This carefully contoured surface allows the Coriolis force to be displayed in isolation.[66][67]

Discs cut from cylinders of dry ice can be used as pucks, moving around almost frictionlessly over the surface of the parabolic turntable, allowing effects of Coriolis on dynamic phenomena to show themselves. To get a view of the motions as seen from the reference frame rotating with the turntable, a video camera is attached to the turntable so as to co-rotate with the turntable, with results as shown in the figure. In the left panel of the figure, which is the viewpoint of a stationary observer, the gravitational force in the inertial frame pulling the object toward the center (bottom ) of the dish is proportional to the distance of the object from the center. A centripetal force of this form causes the elliptical motion. In the right panel, which shows the viewpoint of the rotating frame, the inward gravitational force in the rotating frame (the same force as in the inertial frame) is balanced by the outward centrifugal force (present only in the rotating frame). With these two forces balanced, in the rotating frame the only unbalanced force is Coriolis (also present only in the rotating frame), and the motion is an inertial circle. Analysis and observation of circular motion in the rotating frame is a simplification compared to analysis or observation of elliptical motion in the inertial frame.

Because this reference frame rotates several times a minute rather than only once a day like the Earth, the Coriolis acceleration produced is many times larger and so easier to observe on small time and spatial scales than is the Coriolis acceleration caused by the rotation of the Earth.

In a manner of speaking, the Earth is analogous to such a turntable.[68] The rotation has caused the planet to settle on a spheroid shape, such that the normal force, the gravitational force and the centrifugal force exactly balance each other on a "horizontal" surface. (See equatorial bulge.)

The Coriolis effect caused by the rotation of the Earth can be seen indirectly through the motion of a Foucault pendulum.

Coriolis effects in other areas

Coriolis flow meter

A practical application of the Coriolis effect is the mass flow meter, an instrument that measures the mass flow rate and density of a fluid flowing through a tube. The operating principle involves inducing a vibration of the tube through which the fluid passes. The vibration, though not completely circular, provides the rotating reference frame that gives rise to the Coriolis effect. While specific methods vary according to the design of the flow meter, sensors monitor and analyze changes in frequency, phase shift, and amplitude of the vibrating flow tubes. The changes observed represent the mass flow rate and density of the fluid.[69]

Molecular physics

In polyatomic molecules, the molecule motion can be described by a rigid body rotation and internal vibration of atoms about their equilibrium position. As a result of the vibrations of the atoms, the atoms are in motion relative to the rotating coordinate system of the molecule. Coriolis effects are therefore present, and make the atoms move in a direction perpendicular to the original oscillations. This leads to a mixing in molecular spectra between the rotational and vibrational levels, from which Coriolis coupling constants can be determined.[70]

Gyroscopic precession

When an external torque is applied to a spinning gyroscope along an axis that is at right angles to the spin axis, the rim velocity that is associated with the spin becomes radially directed in relation to the external torque axis. This causes a Coriolis force to act on the rim in such a way as to tilt the gyroscope at right angles to the direction that the external torque would have tilted it. This tendency has the effect of keeping spinning bodies stably aligned in space.

Insect flight

Flies (Diptera) and some moths (Lepidoptera) exploit the Coriolis effect in flight with specialized appendages and organs that relay information about the angular velocity of their bodies.

Coriolis forces resulting from linear motion of these appendages are detected within the rotating frame of reference of the insects' bodies. In the case of flies, their specialized appendages are dumbbell shaped organs located just behind their wings called "halteres".[71]

The fly's halteres oscillate in a plane at the same beat frequency as the main wings so that any body rotation results in lateral deviation of the halteres from their plane of motion.[72]

In moths, their antennae are known to be responsible for the sensing of Coriolis forces in the similar manner as with the halteres in flies.[73] In both flies and moths, a collection of mechanosensors at the base of the appendage are sensitive to deviations at the beat frequency, correlating to rotation in the pitch and roll planes, and at twice the beat frequency, correlating to rotation in the yaw plane.[74][73]

Lagrangian point stability

In astronomy, Lagrangian points are five positions in the orbital plane of two large orbiting bodies where a small object affected only by gravity can maintain a stable position relative to the two large bodies. The first three Lagrangian points (L1, L2, L3) lie along the line connecting the two large bodies, while the last two points (L4 and L5) each form an equilateral triangle with the two large bodies. The L4 and L5 points, although they correspond to maxima of the effective potential in the coordinate frame that rotates with the two large bodies, are stable due to the Coriolis effect.[75] The stability can result in orbits around just L4 or L5, known as tadpole orbits, where trojans can be found. It can also result in orbits that encircle L3, L4, and L5, known as horseshoe orbits.

See also

References

- ^ Frautschi, Steven C.; Olenick, Richard P.; Apostol, Tom M.; Goodstein, David L. (2007). The Mechanical Universe: Mechanics and Heat, Advanced Edition (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-521-71590-4. Extract of page 208

- ^ Bhatia, V.B. (1997). Classical Mechanics: With introduction to Nonlinear Oscillations and Chaos. Narosa Publishing House. p. 201. ISBN 978-81-7319-105-3.

- ^ "Coriolis Effect: Because the Earth turns – Teacher's guide" (PDF). Project ATMOSPHERE. American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ^ Beckers, Benoit (2013). Solar Energy at Urban Scale. John Wiley & Sons. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-118-61436-5. Extract of page 116

- ^ Toossi, Reza (2009). Energy and the Environment: Resources, Technologies, and Impacts. Verve Publishers. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-4276-1867-2. Extract of page 48

- ^ MIT: Flow in rotating environments

- ^ Graney, Christopher M. (2011). "Coriolis effect, two centuries before Coriolis". Physics Today. 64 (8): 8. Bibcode:2011PhT....64h...8G. doi:10.1063/PT.3.1195.

- ^ Graney, Christopher (24 November 2016). "The Coriolis Effect Further Described in the Seventeenth Century". Physics Today. 70 (7): 12–13. arXiv:1611.07912. Bibcode:2017PhT....70g..12G. doi:10.1063/PT.3.3610.

- ^ Truesdell, Clifford. Essays in the History of Mechanics. Springer Science & Business Media, 2012., p. 225

- ^ Persson, A. "The Coriolis Effect: Four centuries of conflict between common sense and mathematics, Part I: A history to 1885." History of Meteorology 2 (2005): 1–24.

- ^ Cartwright, David Edgar (2000). Tides: A Scientific History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 74. ISBN 9780521797467.

- ^ G-G Coriolis (1835). "Sur les équations du mouvement relatif des systèmes de corps". J. De l'Ecole Royale Polytechnique. 15: 144–154.

- ^ Dugas, René and J. R. Maddox (1988). A History of Mechanics. Courier Dover Publications: p. 374. ISBN 0-486-65632-2

- ^ Bartholomew Price (1862). A Treatise on Infinitesimal Calculus : Vol. IV. The dynamics of material systems. Oxford : University Press. pp. 418–420.

- ^ Arthur Gordon Webster (1912). The Dynamics of Particles and of Rigid, Elastic, and Fluid Bodies. B. G. Teubner. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-113-14861-2.

- ^ Edwin b. Wilson (1920). James McKeen Cattell (ed.). "Space, Time, and Gravitation". The Scientific Monthly. 10: 226.

- ^ William Ferrel (November 1856). "An Essay on the Winds and the Currents of the Ocean" (PDF). Nashville Journal of Medicine and Surgery. xi (4): 7–19. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) Retrieved on 1 January 2009. - ^ Anders O. Persson. "The Coriolis Effect:Four centuries of conflict between common sense and mathematics, Part I: A history to 1885" (PDF). Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Gerkema, Theo; Gostiaux, Louis (2012). "A brief history of the Coriolis force". Europhysics News. 43 (2): 16. Bibcode:2012ENews..43b..14G. doi:10.1051/epn/2012202.

- ^ Mark P Silverman (2002). A universe of atoms, an atom in the universe (2 ed.). Springer. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-387-95437-0.

- ^ Taylor (2005). p. 329.

- ^

Cornelius Lanczos (1986). The Variational Principles of Mechanics (Reprint of Fourth Edition of 1970 ed.). Dover Publications. Chapter 4, §5. ISBN 978-0-486-65067-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^

Morton Tavel (2002). Contemporary Physics and the Limits of Knowledge. Rutgers University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-8135-3077-2.

Noninertial forces, like centrifugal and Coriolis forces, can be eliminated by jumping into a reference frame that moves with constant velocity, the frame that Newton called inertial.

- ^ Graney, Christopher M. (2015). Setting Aside All Authority: Giovanni Battista Riccioli and the Science Against Copernicus in the Age of Galileo. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press. pp. 115–125. ISBN 9780268029883.

- ^ Schneider, Stephen H.; Root, Terry L.; Mastrandrea, Michael, eds. (2011). Encyclopedia of Climate and Weather. Vol. 3. Oxford University Press. p. 310.

- ^ John M. Wallace; Peter V. Hobbs (1977). Atmospheric Science: An Introductory Survey. Academic Press, Inc. pp. 368–371. ISBN 978-0-12-732950-5.

- ^ Roger Graham Barry; Richard J. Chorley (2003). Atmosphere, Weather and Climate. Routledge. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-415-27171-4.

- ^ a b The claim is made that in the Falklands in WW I, the British failed to correct their sights for the southern hemisphere, and so missed their targets. John Edensor Littlewood (1953). A Mathematician's Miscellany. Methuen And Company Limited. p. 51. John Robert Taylor (2005). Classical Mechanics. University Science Books. p. 364; Problem 9.28. ISBN 978-1-891389-22-1. For set up of the calculations, see Carlucci & Jacobson (2007), p. 225

- ^ Lakshmi H. Kantha; Carol Anne Clayson (2000). Numerical Models of Oceans and Oceanic Processes. Academic Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-12-434068-8.

- ^ Stephen D. Butz (2002). Science of Earth Systems. Thomson Delmar Learning. p. 305. ISBN 978-0-7668-3391-3.

- ^ James R. Holton (2004). An Introduction to Dynamic Meteorology. Academic Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-12-354015-7.

- ^ Carlucci, Donald E.; Jacobson, Sidney S. (2007). Ballistics: Theory and Design of Guns and Ammunition. CRC Press. pp. 224–226. ISBN 978-1-4200-6618-0.

- ^ Here the description "radially inward" means "toward the axis of rotation". That direction is not toward the center of curvature of the path, however, which is the direction of the true centripetal force. Hence, the quotation marks on "centripetal".

- ^ George E. Owen (2003). Fundamentals of Scientific Mathematics (original edition published by Harper & Row, New York, 1964 ed.). Courier Dover Publications. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-486-42808-6.

- ^ Morton Tavel (2002). Contemporary Physics and the Limits of Knowledge. Rutgers University Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-8135-3077-2.

- ^ James R Ogden; M Fogiel (1995). High School Earth Science Tutor. Research & Education Assoc. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-87891-975-8.

- ^ James Greig McCully (2006). Beyond the moon: A Conversational, Common Sense Guide to Understanding the Tides. World Scientific. pp. 74–76. ISBN 978-981-256-643-0.

- ^ William Menke; Dallas Abbott (1990). Geophysical Theory. Columbia University Press. pp. 124–126. ISBN 978-0-231-06792-8.

- ^ James R. Holton (2004). An Introduction to Dynamic Meteorology. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Academic Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-12-354015-7.

- ^ Brinney, Amanda. "Coriolis Effect – An Overview of the Coriolis Effect". About.com.

- ^ Society, National Geographic (17 August 2011). "Coriolis effect". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- ^ Roger Graham Barry; Richard J. Chorley (2003). Atmosphere, Weather and Climate. Routledge. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-415-27171-4.

- ^ Nelson, Stephen (Fall 2014). "Tropical Cyclones (Hurricanes)". Wind Systems: Low Pressure Centers. Tulane University. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ Cloud Spirals and Outflow in Tropical Storm Katrina from Earth Observatory (NASA)

- ^ Penuel, K. Bradley; Statler, Matt (29 December 2010). Encyclopedia of Disaster Relief. SAGE Publications. p. 326. ISBN 9781452266398.

- ^ John Marshall; R. Alan Plumb (2007). p. 98. Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-558691-7.

- ^ Lowrie, William (1997). Fundamentals of Geophysics (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-521-46728-5. Extract of page 45

- ^ a b Persson, Anders. "The Coriolis Effect – a conflict between common sense and mathematics" (PDF). Norrköping, Sweden: The Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute: 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2005. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rugai, Nick (1 December 2012). Computational Epistemology: From Reality To Wisdom. Lulu.com. p. 304. ISBN 978-1300477235.

- ^ "Bad Coriolis". Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ^ "Flush Bosh". Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ^ "Does the rotation of the Earth affect toilets and baseball games?". 20 July 2009. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ^ "Can somebody finally settle this question: Does water flowing down a drain spin in different directions depending on which hemisphere you're in? And if so, why?". Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ^ Larry D. Kirkpatrick; Gregory E. Francis (2006). Physics: A World View. Cengage Learning. pp. 168–9. ISBN 978-0-495-01088-3.

- ^ Y. A. Stepanyants; G. H. Yeoh (2008). "Stationary bathtub vortices and a critical regime of liquid discharge". Journal of Fluid Mechanics. 604 (1): 77–98. Bibcode:2008JFM...604...77S. doi:10.1017/S0022112008001080.

- ^ Creative Media Applications (2004). A Student's Guide to Earth Science: Words and terms. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-313-32902-9.

- ^ Plait, Philip C. (2002). Bad Astronomy: Misconceptions and Misuses Revealed, from Astrology to the Moon Landing "Hoax" (illustrated ed.). Wiley. p. 22,26. ISBN 978-0-471-40976-2.

- ^ Palin, Michael (1992). Pole to Pole with Michael Palin (illustrated ed.). BBC Books. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-563-36283-8.

- ^ Emery, C. Eugene, Jr. (May 1, 1995). "X-Files coriolis error leaves viewers wondering". Skeptical Inquirer

- ^ Fraser, Alistair. "Bad Coriolis". Bad Meteorology. Pennsylvania State College of Earth and Mineral Science. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ^ Tipler, Paul (1998). Physics for Engineers and Scientists (4th ed.). W.H.Freeman, Worth Publishers. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-57259-616-0.

...on a smaller scale, the coriolis effect causes water draining out a bathtub to rotate anticlockwise in the northern hemisphere...

- ^ Tumlirz, Ottokar (1908). "Ein neuer physikalischer Beweis für die Achsendrehung der Erde". Sitzungsberichte der Math.-nat. Klasse der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften IIa. 117: 819–841.

- ^ Shapiro, Ascher H. (1962). "Bath-Tub Vortex". Nature. 196 (4859): 1080–1081. Bibcode:1962Natur.196.1080S. doi:10.1038/1961080b0.

- ^ (Vorticity, Part 1). Web.mit.edu. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "Do Snipers Compensate for the Earth's Rotation?". Washington City Paper. 25 June 2010. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ When a container of fluid is rotating on a turntable, the surface of the fluid naturally assumes the correct parabolic shape. This fact may be exploited to make a parabolic turntable by using a fluid that sets after several hours, such as a synthetic resin. For a video of the Coriolis effect on such a parabolic surface, see Geophysical fluid dynamics lab demonstration Archived 20 November 2005 at the Wayback Machine John Marshall, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- ^ For a java applet of the Coriolis effect on such a parabolic surface, see Brian Fiedler Archived 21 March 2006 at the Wayback Machine School of Meteorology at the University of Oklahoma.

- ^ John Marshall; R. Alan Plumb (2007). Atmosphere, Ocean, and Climate Dynamics: An Introductory Text. Academic Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-12-558691-7.

- ^ Omega Engineering. "Mass Flowmeters".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ califano, S (1976). Vibrational states. Wiley. pp. 226–227. ISBN 978-0471129967.

- ^ Fraenkel, G.; Pringle, W.S. (21 May 1938). "Halteres of Flies as Gyroscopic Organs of Equilibrium". Nature. 141 (3577): 919–920. Bibcode:1938Natur.141..919F. doi:10.1038/141919a0.

- ^ Dickinson, M. (1999). "Haltere-mediated equilibrium reflexes of the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 354 (1385): 903–916. doi:10.1098/rstb.1999.0442. PMC 1692594. PMID 10382224.

- ^ a b Sane S., Dieudonné, A., Willis, M., Daniel, T. (February 2007). "Antennal mechanosensors mediate flight control in moths" (PDF). Science. 315 (5813): 863–866. Bibcode:2007Sci...315..863S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.205.7318. doi:10.1126/science.1133598. PMID 17290001.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fox, J; Daniel, T (2008). "A neural basis for gyroscopic force measurement in the halteres of Holorusia". Journal of Comparative Physiology. 194 (10): 887–897. doi:10.1007/s00359-008-0361-z. PMID 18751714.

- ^ Spohn, Tilman; Breuer, Doris; Johnson, Torrence (2014). Encyclopedia of the Solar System. Elsevier. p. 60. ISBN 978-0124160347.

Further reading

Physics and meteorology

- Riccioli, G. B., 1651: Almagestum Novum, Bologna, pp. 425–427

(Original book [in Latin], scanned images of complete pages.) - Coriolis, G. G., 1832: "Mémoire sur le principe des forces vives dans les mouvements relatifs des machines." Journal de l'école Polytechnique, Vol 13, pp. 268–302.

(Original article [in French], PDF file, 1.6 MB, scanned images of complete pages.) - Coriolis, G. G., 1835: "Mémoire sur les équations du mouvement relatif des systèmes de corps." Journal de l'école Polytechnique, Vol 15, pp. 142–154

(Original article [in French] PDF file, 400 KB, scanned images of complete pages.) - Gill, A. E. Atmosphere-Ocean dynamics, Academic Press, 1982.

- Robert Ehrlich (1990). Turning the World Inside Out and 174 Other Simple Physics Demonstrations. Princeton University Press. p. Rolling a ball on a rotating turntable; p. 80 ff. ISBN 978-0-691-02395-3.

- Durran, D. R., 1993: Is the Coriolis force really responsible for the inertial oscillation?, Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 74, pp. 2179–2184; Corrigenda. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 75, p. 261

- Durran, D. R., and S. K. Domonkos, 1996: An apparatus for demonstrating the inertial oscillation, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 77, pp. 557–559.

- Marion, Jerry B. 1970, Classical Dynamics of Particles and Systems, Academic Press.

- Persson, A., 1998 [1] How do we Understand the Coriolis Force? Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 79, pp. 1373–1385.

- Symon, Keith. 1971, Mechanics, Addison–Wesley

- Akira Kageyama & Mamoru Hyodo: Eulerian derivation of the Coriolis force

- James F. Price: A Coriolis tutorial Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (2003)

- McDonald, James E. (May 1952). "The Coriolis Effect" (PDF). Scientific American: 72–78. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

Everything that moves over the surface of the Earth – water, air, animals, machines and projectiles – sidles to the right in the Northern Hemisphere and to the left in the Southern

. Elementary, non-mathematical; but well written.

Historical

- Grattan-Guinness, I., Ed., 1994: Companion Encyclopedia of the History and Philosophy of the Mathematical Sciences. Vols. I and II. Routledge, 1840 pp.

1997: The Fontana History of the Mathematical Sciences. Fontana, 817 pp. 710 pp. - Khrgian, A., 1970: Meteorology: A Historical Survey. Vol. 1. Keter Press, 387 pp.

- Kuhn, T. S., 1977: Energy conservation as an example of simultaneous discovery. The Essential Tension, Selected Studies in Scientific Tradition and Change, University of Chicago Press, 66–104.

- Kutzbach, G., 1979: The Thermal Theory of Cyclones. A History of Meteorological Thought in the Nineteenth Century. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 254 pp.

External links

- The definition of the Coriolis effect from the Glossary of Meteorology

- The Coriolis Effect — a conflict between common sense and mathematics PDF-file. 20 pages. A general discussion by Anders Persson of various aspects of the coriolis effect, including Foucault's Pendulum and Taylor columns.

- The coriolis effect in meteorology PDF-file. 5 pages. A detailed explanation by Mats Rosengren of how the gravitational force and the rotation of the Earth affect the atmospheric motion over the Earth surface. 2 figures

- 10 Coriolis Effect Videos and Games- from the About.com Weather Page

- Coriolis Force – from ScienceWorld

- Coriolis Effect and Drains An article from the NEWTON web site hosted by the Argonne National Laboratory.

- Catalog of Coriolis videos

- Coriolis Effect: A graphical animation, a visual Earth animation with precise explanation

- An introduction to fluid dynamics SPINLab Educational Film explains the Coriolis effect with the aid of lab experiments

- Do bathtubs drain counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere? by Cecil Adams.

- Bad Coriolis. An article uncovering misinformation about the Coriolis effect. By Alistair B. Fraser, Emeritus Professor of Meteorology at Pennsylvania State University

- The Coriolis Effect: A (Fairly) Simple Explanation, an explanation for the layperson

- Observe an animation of the Coriolis effect over Earth's surface

- Animation clip showing scenes as viewed from both an inertial frame and a rotating frame of reference, visualizing the Coriolis and centrifugal forces.

- Vincent Mallette The Coriolis Force @ INWIT

- NASA notes

- Interactive Coriolis Fountain lets you control rotation speed, droplet speed and frame of reference to explore the Coriolis effect.

- Rotating Co-ordinating Systems, transformation from inertial systems

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\mathbf {a} _{\text{Cor}}&=-2\left[-\omega v\left(\sin \alpha -\omega t\cos \alpha \right),\ \omega v\left(\cos \alpha +\omega t\sin \alpha \right)\right]\\&=2\omega v\left(\sin \alpha ,\ -\cos \alpha \right)-2\omega ^{2}\mathbf {r} _{B}(t)\ .\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f7bcadd5ccae2f56930c1bf34d7b60818e526a83)