Jean de Florette

| Jean de Florette | |

|---|---|

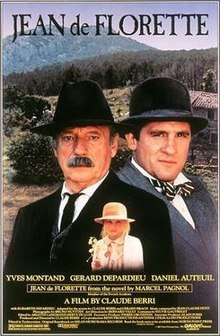

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Claude Berri |

| Written by | Claude Berri Gérard Brach Marcel Pagnol |

| Produced by | Pierre Grunstein Alain Poiré |

| Starring | Yves Montand Gérard Depardieu Daniel Auteuil |

| Cinematography | Bruno Nuytten |

| Edited by | Noëlle Boisson Sophie Coussein Hervé de Luze Jeanne Kef Arlette Langmann Corinne Lazare Catherine Serris |

| Music by | Jean-Claude Petit Giuseppe Verdi |

| Distributed by | Orion Pictures (USA) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 120 minutes |

| Countries | France Italy[1] |

| Language | French |

| Budget | $17 million |

| Box office | $87 million |

Jean de Florette (French pronunciation: [ʒɑ̃ də flɔʁɛt]) is a 1986 period drama film directed by Claude Berri, based on a novel by Marcel Pagnol. It is followed by Manon des Sources. The film takes place in rural Provence, where two local farmers plot to trick a newcomer out of his newly inherited property. The film starred three of France's most prominent actors – Gérard Depardieu, Daniel Auteuil, who won a BAFTA award for his performance, and Yves Montand in one of his last roles before his death.

The film was shot back to back with Manon des Sources, over a period of seven months. At the time the most expensive French film ever made, it was a great commercial and critical success, both domestically and internationally, and was nominated for eight César awards, and ten BAFTAs. The success of the two films helped promote Provence as a tourist destination.

Plot

The story takes place outside a small village in Provence, France, shortly after the First World War. Ugolin Soubeyran (Auteuil) returns early in the morning from his military service and wakes up his uncle César (Montand), called in the local dialect 'Le Papet' meaning grandfather. Ugolin stays only briefly to talk, as he is eager to get to his own place farther up in the mountains. Here he throws himself into a project that—at first—he keeps secret from Papet. He eventually reveals that the project consists of growing carnations. Papet is at first skeptical, but he is convinced when the flowers get a good price at the local market. They decide the project is worthy of expansion, and together they go to see the neighboring farmer known as Pique-Bouffigue, to buy his land.

The land in question is apparently "dry", but Papet knows of a source of water, a spring, that can solve that problem. Pique-Bouffigue does not want to sell, and an altercation breaks out when he insults the Soubeyran family. In the fight, Pique-Bouffigue is knocked unconscious. He becomes friendly (as a result of memory loss from a head wound) but dies about a year after the fight. Papet sees this as an opportunity, so after the funeral, Papet and Ugolin dig out the rubble that is filling the spring, plug the hole, and cover it with cement and then earth. Unknown to them, they are seen blocking the spring by a poacher.

The property descends to the dead man's sister, Florette, a childhood friend of Papet, who married the blacksmith in another village whilst Papet was recovering in a military hospital in Algeria. He writes to a common friend for news on Florette and finds that she died the same day his letter arrived. The property thereby descends to her son who is a tax collector and "unfortunately, by God's will...he's a hunchback". To discourage Florette's son from taking up residence, Ugolin breaks many tiles on the roof of the house.

Florette's son (Depardieu), Jean, arrives with his wife Aimée and young daughter Manon, and the Soubeyrans' hopes of an easy takeover are soon shattered. Florette's son is called Jean Cadoret, but Ugolin, in the local custom, calls him Jean de Florette. Jean makes it clear that he has no intention of selling, but plans to take up residence and live off the land. He has a grand scheme for making the farm profitable within two years, involving breeding rabbits and feeding them off cucurbit. Jean does not know about the blocked spring, only of a more distant one, and is relying on rainfall to fill a cistern with water for supplying livestock and irrigating crops. The distant spring, where an old Italian couple lives, is 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) away and also part of the property. Jean believes the needs of the farm can be met from here. Ugolin is discouraged, but Papet tells him to befriend Jean and gain his confidence. They also keep secret from him the fact that—while average rainfall for the surrounding region is sustainable—the area where Florette's farm lies rarely gets any of this rain. Meanwhile, the two work to turn the local community against the newcomer, who is described merely as a hunchbacked former tax collector, since the deceased Pique-Bouffigue had cousins in the village who know about the blocked spring and would tell Jean about it should they come to trust him.

Jean initially makes progress, and earns a small profit from his rabbit farm. In the long run, getting water proves a problem, and dragging it all the way from the distant spring becomes a backbreaking experience. Jean asks to borrow Ugolin's mule, but is met only with vague excuses. Then, when the rain does come, it falls on the surrounding area but not where it is needed. Jean loudly berates God, whom he thinks has already given him enough trouble by deforming him. Later, the dusty winds of the sirocco also arrive, bringing the farm to near-catastrophe. Jean is undeterred, and decides to dig a well. At this point Ugolin sees it fitting to try and convince Jean that his project is hopeless, and that he might be better off selling. Jean asks how much he could expect to receive for the farm, and Ugolin gives an estimate of around 8,000 francs. Jean has no intention of leaving though, but wants to use the value of the property to take up a mortgage of half that sum. Ugolin is not happy, but Papet again sees opportunity: he will himself grant the mortgage; that way he will either earn the interest, or drive Jean away for good. From the money Jean buys dynamite to finish the well, but in his first blast is hit by a flying rock and falls into the cavity. At first the injuries seem minor, but it turns out his spine is fractured and when the doctor arrives he declares Jean dead. Ugolin returns with the news to Papet, who asks him why he's crying. "It is not me who's crying," he responds, "it's my eyes".

Aimée and Manon cannot remain on the farm, and Papet offers to buy them out. As mother and daughter are packing their belongings, Papet and Ugolin make their way to where they blocked the spring, to pull out the plug. Manon follows them, and when she sees what the two are doing, understands and gives out a shriek. The men hear it, but quickly dismiss the sound as that of a buzzard making a kill. As Papet performs a mock baptism of his nephew in the cold water of the spring, the film ends with the caption "end of part one".

Cast

- Yves Montand as César Soubeyran / "Le Papet": In the local dialect "Papet" is an affectionate term for "grandfather".[2] César is the proud patriarch of a dying family, and his only known relative is his nephew Ugolin. Eager to restore his family's position, he manipulates his nephew to do his bidding.[3] For Yves Montand the filming experience was particularly trying because his wife of thirty-three years, Simone Signoret, died during filming.[4] Montand himself died in 1991, and the two films were among the last of a cinematic career spanning forty-five years.[5] Having grown up in nearby Marseilles, he visited the location before filming started, and endeared himself with the locals.[4]

- Daniel Auteuil as Ugolin: Ugolin is César's "rat-faced sub-intelligent nephew".[6] Somewhat more conscientious than his uncle, he is nevertheless persuaded to carry through with the diabolical plan.[2] Auteuil used a prosthetic nose to make the character uglier.[7] The role represented a great change for Auteuil. He had previously tended to play "smart, funny, urban hipster types", and the role as Ugolin – which earned him both a BAFTA and a César – was a great step forward in his career.[2]

- Gérard Depardieu as Jean Cadoret / "Jean de Florette": Jean is a city man with a romantic idea of the countryside, yet obstinate and hard-working.[2] Depardieu was well established as a versatile actor even before this role.[7] Seemingly impervious to the great pressure on the film crew, he earned a reputation on the set for "fooling about, telling jokes, swearing at planes interrupting the shot and never knowing his lines until the camera was rolling".[4]

- Élisabeth Depardieu (Gérard Dépardieu's real-life wife[6]) as Aimée Cadoret: Jean's beautiful wife is a former opera singer, who has named her daughter after her favourite role, Manon Lescaut.[7]

- Ernestine Mazurowna as Manon, the daughter of Jean and Aimée.

Production

Marcel Pagnol's 1953 film Manon des Sources was four hours long, and subsequently cut by its distributor. The end result left Pagnol dissatisfied, and led him to retell the story as a novel.[6][8] The first part of the novel, titled Jean de Florette, was an exploration of the background for the film; a prequel of sorts. Together the two volumes made up the work Pagnol called L'Eau des collines (The Water of the Hills).[2] Berri came across Pagnol's book by chance in a hotel room, and was captivated by it. He decided that in order to do the story justice it had to be made in two parts.[2]

Jean de Florette was filmed in and around the Vaucluse department of Provence, where a number of different places have been mentioned as filming locations.[9] La Treille, east of Marseille, in the Bouches-du-Rhône department, was the village where Pagnol had shot the original film. The village is now within the city limits of Marseille and has undergone extensive development since the 1950s, so Berri had to find alternatives.[2] For the village of the story he settled on Mirabeau (65 km to the north), while Jean de Florette's house is located in Vaugines, where the church from the film can also be found.[4] The market scenes were filmed in Sommières in the Gard, and the story's Les Romarins was in reality Riboux in the Var.[8]

Extensive work was put into creating a genuine and historically correct atmosphere for the film. The facades of the houses of Mirabeau had to be replaced with painted polystyrene, to make them look older, and all electric wires were put underground.[4] Meanwhile, in Vaugines, Berri planted a dozen olive trees twelve months before filming started, and watered them throughout the waiting period, and for the second installment planted 10,000 carnations on the farm.[2]

Jean de Florette and Manon des Sources were filmed together, over a period of thirty weeks, from May to December 1985. This allowed Berri to show the dramatic seasonal changes of the Provençal landscape.[8] At $17 million, it was at the time the most expensive film project in French history.[6] The long filming period and the constantly increasing cost put a great burden on the actors, many of whom frequently had to return to Paris for television or theatre work.[4] Once completed, the release of the film was a great national event. A special promotional screening before the film's official release 27 August 1986, was attended by then Minister of Culture Jack Lang.[8] The musical score is based around the aria Invano Alvaro from Giuseppe Verdi's 1862 opera La forza del destino.

Reception

The film was a great success in its native France, where it was seen by over seven million people.[10] It also performed very well internationally; in the United States it grossed nearly five million US$, placing it among the 100 most commercially successful foreign-language films shown there.[11]

Critical reception for Jean de Florette was almost universally positive.[12] Rita Kempley, writing for The Washington Post, compared the story to the fiction of William Faulkner. Allowing that it could indeed be "a definitive French masterwork", she reserved judgement until after the premiere of the second part, as Jean de Florette was only a "half-movie", "a long, methodic buildup, a pedantically paced tease".[7] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times commented on Berri's exploration of human character, "the relentlessness of human greed, the feeling that the land is so important the human spirit can be sacrificed to it". Ebert gave the film three-and-a-half out of four stars.[13]

The staff reviewer for the entertainment magazine Variety highlighted – as other reviewers did as well – the cinematography of Bruno Nuytten (an effort that won Nuytten a BAFTA award and a César nomination).[14] The reviewer commended Berri particularly for the work done with the small cast, and for his decision to stay true to Pagnol's original story.[6] Richard Bernstein, reviewing the film for The New York Times, wrote it was "like no other film you've seen in recent years". He called it an updated, faster-paced version of Pagnol, where the original was still recognisable.[2] The newspaper lists the film among the "Best 1000 Movies Ever Made".[15] Later reviews show that the film has stood up to the passage of time. Tasha Robinson, reviewing the DVD release of the two films for The A.V. Club in 2007, called the landscape, as portrayed by Berri and Nuytten, "almost unbearably beautiful". Grading the films 'A', she called them "surprisingly tight and limber" for a four-hour film cycle.[3]

Awards

Nominated for a total of eight César awards in 1987 – including 'Best Film', 'Best Director' and 'Best Cinematography' – Jean de Florette won only one, 'Best Actor' for Daniel Auteuil.[16] At the BAFTA awards the next year it fared better, winning awards for 'Best Actor in a Supporting Role' (Auteuil), 'Best Cinematography', 'Best Film' and 'Best Adapted Screenplay'. The film also earned six more nominations, including both Depardieu and Montand in the 'Best Actor'-category, as well as 'Best Direction' and 'Best Foreign Language Film'.[17] Amongst other honours for the film were a U.S. National Board of Review award for 'Best Foreign Language Film',[18] and a 'Best Foreign Language Film' nomination at the 1988 Golden Globes.[19] It was also nominated for the Golden Prize at the 15th Moscow International Film Festival.[20]

Legacy

Jean de Florette and Manon des Sources have been interpreted as part of a wider trend in the 1980s of so-called 'heritage cinema': period pieces and costume dramas that celebrated the history, culture and landscape of France. It was the official policy of President François Mitterrand, elected in 1981, and particularly his Minister of Culture Jack Lang, to promote these kinds of films through increased funding of the ailing French film industry. Berri's pair of films stand as the most prominent example of this effort.[8][21] It has also been suggested that the treatment given the outsider Jean de Florette by the locals was symbolic of the growing popularity of the anti-immigration movement, led by politicians like Jean-Marie Le Pen.[8]

The two films are often seen in conjunction with Peter Mayle's book A Year in Provence, as causing increased interest in, and tourism to, the region of Provence, particularly among the British.[22] The films inspired a vision of the area as a place of rural authenticity, and were followed by an increase in British home ownership in southern France.[23] As late as 2005, the owners of the house belonging to Jean de Florette in the movie were still troubled by tourists trespassing on their property.[4]

Jean de Florette served as an inspiration for the 1998 Malayalam–language Indian film Oru Maravathoor Kanavu.[24]

Ranked No. 60 in Empire magazine's "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema" in 2010.[25]

References

- ^ Erickson, Hal. "Jean de Florette: Overview – Allmovie". Allmovie. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bernstein, Richard (21 June 1987). "Film; France's savoury tale of fate". New York Times. Retrieved 27 July 2008.

- ^ a b Robinson, Tasha (8 August 2007). "Jean De Florette / Manon Of The Spring". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Falconer, Kieran (8 August 2005). "The landscape of Manon des Sources". The Times. London: News Corporation. Retrieved 27 July 2008.

- ^ "Yves Montand". IMDb. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ^ a b c d e "Jean de Florette". Variety. 1 January 1986. Retrieved 27 July 2008.

- ^ a b c d Kempley, Rita (24 July 1987). "Jean de Florette (NR)". Washington Post. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Powrie, Phil (2006). The Cinema of France. Wallflower Press. pp. 185–94. ISBN 1-904764-46-0.

- ^ "Filming locations for Jean de Florette (1986)". IMDb. Retrieved 27 July 2008.

- ^ "Box office / business for Jean de Florette (1986)". IMDb. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ^ "Jean de Florette". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ^ "Jean de Florette (1987)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 18 November 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ebert, Roger (7 August 1987). "Jean de Florette". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ^ "Awards for Bruno Nuytten". IMDb. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ^ "The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made". The New York Times. 29 April 2003. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ^ "1987 – 12ème Cérémonie des César" (in French). Académie des César. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ^ "1987". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ^ "1987 Award Winners". National Board of Review of Motion Pictures. 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ^ "Awards for Jean de Florette (1986)". IMDb. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ^ "15th Moscow International Film Festival (1987)". MIFF. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hayward, Susan (2005). French National Cinema. Routledge. pp. 300–1. ISBN 0-415-30783-X.

- ^ "Jean de Florette (X) ****". Southern Daily Echo. 7 February 2003. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ^ Crouch, David; Rhona Jackson; Felix Thompson (2005). The Media and the Tourist Imagination: Converging Cultures. Routledge. pp. 144–7. ISBN 0-415-32626-5.

- ^ "Oru Maravathoor Kanavu (dir. Lal Jose, 1998)". Totallyfilmi.com. 30 October 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema – 60. Jean de Florette". Empire.

External links

- Jean de Florette at IMDb

- Template:Allmovie title

- Jean de Florette at Rotten Tomatoes

- Trailer (1986)

- Transcript

- Use dmy dates from March 2012

- 1986 films

- French films

- Italian films

- French-language films

- 1980s drama films

- Films based on works by Marcel Pagnol

- Films directed by Claude Berri

- Films featuring a Best Actor César Award-winning performance

- Films set in France

- France in fiction

- French drama films

- Best Film BAFTA Award winners

- Films whose writer won the Best Adapted Screenplay BAFTA Award

- Screenplays by Claude Berri

- Screenplays by Gérard Brach

- Films about agriculture