Brexit

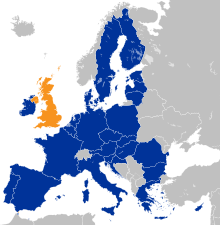

Withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union, often shortened to Brexit (a portmanteau of "British" or "Britain" and "exit"),[1][2] is a political goal that has been pursued by various individuals, advocacy groups, and political parties since the United Kingdom (UK) joined the precursor of the European Union (EU) in 1973. Withdrawal from the European Union is a right of EU member states under Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union.

In 1975, a referendum was held on the country's membership of the European Economic Community (EEC), later known as the EU. The outcome of the vote was in favour of the country continuing to be a member of the EEC.

The UK electorate again addressed the question on June 23, 2016, in a referendum on the country's membership. This referendum was arranged by parliament when it passed the European Union Referendum Act 2015.

For the country's continued membership in the EU, the term Bremain is sometimes used (portmanteau of "Britain" and "remain"), although "Remain" is more frequently encountered.

Background

The UK was not a signatory to the Treaty of Rome which created the EEC in 1957. The country subsequently applied to join the organization in 1963 and again in 1967, but both applications were vetoed by the then President of France, Charles de Gaulle, ostensibly because "a number of aspects of Britain's economy, from working practices to agriculture" [had] "made Britain incompatible with Europe."[3]

Once de Gaulle had relinquished the French presidency, the UK made a third application for membership, which was successful. On 1 January 1973 the United Kingdom joined the EEC, then commonly referred to in the UK as the Common Market. This was done under the Conservative government of Edward Heath.[4] The opposition Labour Party, led by Harold Wilson, contested the October 1974 general election with a commitment to renegotiate Britain's terms of membership of the EEC and then hold a referendum on whether to remain in the EEC on the new terms.

1975 referendum

In 1975 the United Kingdom held a referendum on whether the UK should remain in the EEC. All of the major political parties and mainstream press supported continuing membership of the EEC. However, there were significant splits within the ruling Labour party, the membership of which had voted 2:1 in favour of withdrawal at a one-day party conference on 26 April 1975. Since the cabinet was split between strongly pro-European and strongly anti-European ministers, Harold Wilson suspended the constitutional convention of Cabinet collective responsibility and allowed ministers to publicly campaign on either side. Seven of the twenty-three members of the cabinet opposed EEC membership.[5]

On 5 June 1975, the electorate were asked to vote yes or no on the question: "Do you think the UK should stay in the European Community (Common Market)?" Every administrative county in the UK had a majority of "Yes", except the Shetland Islands and the Outer Hebrides. In line with the outcome of the vote, the United Kingdom remained a member of the EEC.[6]

| Yes votes | Yes (%) | No votes | No (%) | Turnout (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17,378,581 | 67.2 | 8,470,073 | 32.8 | 64.5 |

Between referendums

The opposition Labour Party campaigned in the 1983 general election on a commitment to withdraw from the EEC.[7] It was heavily defeated as the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher was re-elected. The Labour Party subsequently changed its policy.[7]

As a result of the Maastricht Treaty, the EEC became the European Union on 1 November 1993.[8] Starting as a purely economic union, the organization has evolved into a political union. The name change has reflected this.[9]

The Referendum Party was formed in 1994 by Sir James Goldsmith to contest the 1997 general election on a platform of providing a referendum on the UK's membership of the EU.[10] It fielded candidates in 547 constituencies at that election and won 810,860 votes, 2.6% of total votes cast.[11] It failed to win a single parliamentary seat as its vote was spread out, losing its deposit (funded by Goldsmith) in 505 constituencies.[11]

The United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), a Eurosceptic political party, was also formed in the early 1990s. It achieved third place in the UK during the 2004 European elections, second place in the 2009 European elections and first place in the 2014 European elections, with 27.5% of the total vote. This was the first time since the 1910 general election that any party other than the Labour or Conservative parties had taken the largest share of the vote in a nationwide election.[12]

In the 2015 general election UKIP took 12.6% of the total vote and won a seat in Parliament, the first they had taken in a general election.[13]

2016 referendum

In 2012, Prime Minister David Cameron rejected calls for a referendum on the UK's EU membership, but suggested the possibility of a future referendum to gauge public support.[14][15] According to the BBC,[16]

The prime minister acknowledged the need to ensure the UK's position within the European Union had "the full-hearted support of the British people" but they needed to show "tactical and strategic patience".

— UK Politics, BBC

In January 2013, Cameron announced that a Conservative government would hold an in-out referendum on EU membership before the end of 2017, on a renegotiated package, if elected in 2015.[17]

The Conservative Party won the 2015 general election. Soon afterwards the European Union Referendum Act 2015 was introduced into parliament to enable the referendum. Despite being in favour of remaining in a reformed European Union himself,[18] Cameron announced that Conservative Ministers and MPs were free to campaign in favour of remaining in the EU or leaving it, according to their conscience. This decision came after mounting pressure for a free vote for ministers.[19] In an exception to the usual rule of cabinet collective responsibility, Cameron allowed cabinet ministers to publicly campaign for EU withdrawal.[20]

In a speech to the House of Commons on 22 February 2016,[21] Cameron announced a referendum date of 23 June 2016 and set out the legal framework for withdrawal from the European Union in circumstances where there was a referendum majority vote to leave, citing Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty.[22] Cameron spoke of an intention to trigger the Article 50 process immediately following a leave vote and of the "two-year time period to negotiate the arrangements for exit".[citation needed]

Campaign groups

The official campaign group for leaving the EU is Vote Leave.[23] Other major campaign groups include Leave.EU,[24] Grassroots Out, and Better Off Out,[25] while non-EU affiliated organisations have also campaigned for the United Kingdom's withdrawal, such as the Commonwealth Freedom of Movement Organisation.[26]

The official campaign to stay in the EU, chaired by Stuart Rose, is known as Britain Stronger in Europe, or informally as Remain. Other campaigns supporting remaining in the EU include Conservatives In,[27] Labour In for Britain,[28] #INtogether (Liberal Democrats),[29] Greens For A Better Europe,[30] Scientists for EU,[31] Environmentalists For Europe,[32] Universities for Europe[33] and Another Europe is Possible.[34]

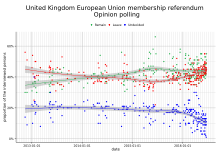

Public opinion

Public opinion on whether the UK should leave the EU or stay has varied. An October 2015 analysis of polling suggests that younger voters tend to support remaining in the EU, whereas those older tend to support leaving, but there is no gender split in attitudes.[35]

Procedure for leaving the EU

Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union provides that: "Any Member State may decide to withdraw from the Union in accordance with its own constitutional requirements."[36] Article 50 was inserted by the Lisbon Treaty, before which the treaties were silent on the possibility of withdrawal. Once a member state has notified the European Council of its intent to leave the EU, a negotiation period begins during which a leaving agreement is to be negotiated setting out the arrangements for the withdrawal and outlining the country's future relationship with the Union. For the agreement to enter into force it needs to be approved by at least 72 percent of the continuing member states representing at least 65 percent of their population, and the consent of the European Parliament.[36] The treaties cease to apply to the member state concerned on the entry into force of the leaving agreement, or in the absence of such an agreement, two years after the member state notified the European Council of its intent to leave, although this period can be extended by unanimous agreement of the European Council.[37]

The 2016 referendum does not directly bind the government to specific actions; in this, it is similar to the Scottish independence referendum, 2014. Indeed it does not require the government to begin the Article 50 procedure or set any time limit for this to be done,[38] although David Cameron has said that he would immediately invoke Article 50 in the event of a leave victory.[39]

A number of commentators have suggested the possibility of a second referendum to "confirm" the decision to leave following negotiations, but there is no established formal process for such a move. The Constitution Unit argues that Article 50 negotiations cannot be used to renegotiate the conditions of future membership and that Article 50 does not provide the legal basis of withdrawing a decision to leave.[38] Both the British government and a substantial number of European politicians have stated they would expect a leave vote to be followed by withdrawal, not by a second vote.[40]

Subsequent relationship with the remaining EU members

Were the UK electorate to vote to leave the EU, its subsequent relationship with the remaining EU members could take several forms. A research paper presented to the UK Parliament proposed a number of alternatives to membership which would continue to allow access with the EU internal market. These include remaining in the European Economic Area (EEA) as a European Free Trade Association (EFTA) member, or seeking to negotiate bilateral terms along the Swiss model with a series of interdependent sectoral agreements.[41]

Were the UK to join the EEA as an EFTA member, it would have to sign up to EU internal market legislation without being able to participate in its development or vote on its content. However, the EU is required to conduct extensive consultations with non-EU members beforehand via its many committees and cooperative bodies.[42][43] Some EU Law originates from various international bodies on which non-EU EEA countries have a seat.

The EEA Agreement (EU and EFTA members except Switzerland) does not cover Common Agriculture and Fisheries Policies, Customs Union, Common Trade Policy, Common Foreign and Security Policy, direct and indirect taxation, and Police and Judicial Co-operation in Criminal Matters, leaving EFTA members free to set their own policies in these areas;[44] however, EFTA countries are required to contribute to the EU Budget in exchange for access to the internal market.[45][46]

The EEA Agreement and the agreement with Switzerland cover free movement of goods, and free movement of people.[citation needed] Many supporters of Brexit want to prevent people from EU countries with low salaries to work in the UK.[citation needed] But if the UK gets an EEA Agreement, it would include free movement for EU and EEA citizens.[citation needed] Others[who?] present ideas of a Swiss solution, that is tailor-made agreements between the UK and the EU, but EU representatives have claimed they would not support such a solution.[citation needed] The Swiss agreements contain free movement for EU citizens.[citation needed]

Opinions on the results of a withdrawal

A report by Tim Oliver of the German Institute for International and Security Affairs expanded analysis of what a British withdrawal could mean for the EU: the report argues a UK withdrawal "has the potential to fundamentally change the EU and European integration. On the one hand, a withdrawal could tip the EU towards protectionism, exacerbate existing divisions, or unleash centrifugal forces leading to the EU's unravelling. Alternatively, the EU could free itself of its most awkward member, making the EU easier to lead and more effective."[47]

Leading figures both supportive and not of Scottish independence have suggested that in the event the UK as a whole votes to leave the EU but Scotland as a whole votes to remain in the EU (as the polls currently suggest with a large margin [48] ), a second Scottish Independence referendum may be precipitated.[49][50] Former Labour Scottish First Minister Henry McLeish has said that he would support Scottish independence under such circumstances.[51] It has also been pointed out that upon the UK's exit from the EU, many of the powers and competencies of the EU institutions would be repatriated to Holyrood and not Westminster.[52] Currently, Scotland exports three and a half times more to the rest of the UK than to the rest of the EU.[53] The pro-union Scotland in Union has suggested that an independent Scotland within the EU would face trade barriers with a post-Brexit UK and face additional costs for re-entry to the EU.[53]

Enda Kenny, the Taoiseach of Ireland, has warned that a UK exit of the European Union could damage the Northern Ireland peace process.[54] Northern Ireland Secretary Theresa Villiers denounced the suggestion as "scaremongering of the worst possible kind".[55] It has been suggested by a member of Germany's parliamentary finance committee that a "bilateral solution" between the UK and Ireland could be negotiated quickly after a leave vote.[56]

Regional President of Nord-Pas-de-Calais-Picardie Xavier Bertrand stated in February 2016 that "If Britain leaves Europe, right away the border will leave Calais and go to Dover. We will not continue to guard the border for Britain if it’s no longer in the European Union" indicating that the juxtaposed controls would end with a leave vote. French Finance Minister Emmanuel Macron also suggested the agreement would be "threatened" by a leave vote.[57] These claims have been disputed, as the Le Touquet treaty enabling juxtaposed controls was not debated from within the EU, and would not be legally void upon leaving.[58]

UK universities rely on the EU for around 16% of their total research funding, and are disproportionately successful at winning EU-awarded research grants. This has raised questions about how such funding would be impacted by a British exit.[59]

St George's, University of London professor Angus Dalgleish pointed out that Britain paid much more into the EU research budget than it received, and that existing European collaboration such as CERN and European Molecular Biology Laboratory began long before the Lisbon Treaty, adding that leaving the EU would not damage Britain's science.[60]

London School of Economics emeritus professor Alan Sked pointed out that non-EU countries such as Israel and Switzerland signed agreements with the EU in terms of the funding of collaborative research and projects, and suggested that if Britain left the EU, Britian would be able to reach a similar agreement with the EU, pointing out that educated people and reseach bodies would easily find some financial arrangement during an at least 2-year transition period which was related to Article 50 of Treaty of European Union(TEU).[61]

In 2015, Chief Minister of Gibraltar Fabian Picardo suggested that Gibraltar would attempt to remain part of the EU in the event the UK voted to leave,[62] but reaffirmed that, regardless of the result, the territory would remain British.[63] In a letter to the (UK) Foreign Affairs Select Committee, he requested that Gibraltar be considered in negotiations post-Brexit.[64]

The UK treasury have estimated that being in the EU has a strong positive effect on trade and as a result the UK's trade would be worse off if it left the EU.[65]

Supporters of withdrawal from the EU have argued that by ceasing to make a net contribution to the EU would allow for some cuts to taxes and/or increases in government spending[66] However, Britain would still be required to make contributions to the EU budget if it opted to remain in the European Free Trade Area.[45] The Institute for Fiscal Studies notes that most majority of forecasts of the impact of Brexit on the UK economy would leave the government with less money to spend even if it no longer had to pay into the EU.[67]

Former Chancellor of the Exchequer Norman Lamont argued that if Britain left the EU, the EU would not impose retaliatory tariffs on British products, pointing out that the EU needed a trade agreement with Britain as German car manufacturers wanted to sell their cars to the world's fifth biggest market.[68] Lamont argued that the EFTA option was irrelevant and that Britain and the EU would agree on a trade pact which tailored to Britain's needs.[68]

James Dyson argued that it would be self-defeating for the EU to impose retaliatory tariffs on British products because if the EU imposed a tariff on Britain, Britain would do impose a retaliatory tariff on the EU, claiming that Britain bought 100 billion pounds worth of the EU's goods and sold 10 billion pounds worth of Britain's goods.[69] However, proportionally, the government responded that "EU exports to the UK are worth 3% of EU GDP, while UK exports to the EU are worth 13% of UK GDP – four times more."[70]

On 15 June 2016, Vote Leave, the official Leave campaign, presented its roadmap to lay out what would happen if Britain left the EU.[71] The blueprint suggetsed that parliament would pass laws: Finance Bill to scrap VAT on tampon and household energy bills; Asylum and Immigration Control Bill to end the automatic right of EU citizens to enter Britain; National Health Service (Funding Target) Bill to get an extra 100 million pounds a week; European Union Law (Emergency Provisions) Bill; Free Trade Bill to start to negotiate its own deals with non-EU countries; and European Communities Act 1972 (Repeal) Bill to end the European Court of Justice's jurisdiction over Britain and stop making contribution to the EU budget.[71]

Former Chairman of the Conservative Party Norman Tebbit said that David Cameron should resign as prime minister if the UK voted for an EU exit. According to a poll conducted by Ipsos MORI in late March 2016, 48 per cent of UK voters thought that Cameron should resign if the UK voted to leave the EU.[72] David Cameron said that he would stay in office after the referendum, while former Chancellor of the Exchequer Kenneth Clarke said that the Prime Minister would not last 30 seconds if Britain voted to leave the EU.[73]

Former Bundesbank President Axel Weber said that leaving the EU would not deal a major blow to London's status as one of the top financial hubs.[74]

Voting result

They left

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2016) |

According to the BBC the first results were expected around midnight on June 23, with the full results by breakfast time on 24 June.

See also

References

- ^ "The UK's EU referendum: All you need to know". BBC News. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ "Google search for Brexit plus "British and exit"".

- ^ "1967: De Gaulle says 'non' to Britain – again". BBC News. 27 November 1976. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ "1973: Britain joins the EEC". BBC News. 1 January 1973. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ DAvis Butler. "The 1975 Referendum" (PDF). Eureferendum.com. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "Research Briefings – The 1974–75 UK Renegotiation of EEC Membership and Referendum". Researchbriefings.parliament.uk. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ a b Vaidyanathan, Rajini (4 March 2010). "Michael Foot: What did the 'longest suicide note' say?". BBC News Magazine. BBC. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ "EUROPA – EU treaties". Europa.eu. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "EUROPA – The EU in brief". Europa.eu. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ Wood, Nicholas (28 November 1994). "Goldsmith forms a Euro referendum party". The Times. p. 1.

- ^ a b "UK Election 1997". Politicsresources.net. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ "10 key lessons from the European election results". The Guardian. 26 May 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ Matt Osborn (7 May 2015). "2015 UK general election results in full". the Guardian.

- ^ Nicholas Watt (29 June 2012). "Cameron defies Tory right over EU referendum: Prime minister, buoyed by successful negotiations on eurozone banking reform, rejects 'in or out' referendum on EU". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

David Cameron placed himself on a collision course with the Tory right when he mounted a passionate defence of Britain's membership of the EU and rejected out of hand an 'in or out' referendum.

- ^ Sparrow, Andrew (1 July 2012). "PM accused of weak stance on Europe referendum". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

Cameron said he would continue to work for 'a different, more flexible and less onerous position for Britain within the EU'.

- ^ "David Cameron 'prepared to consider EU referendum'". BBC News. BBC. 1 July 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

Mr Cameron said … he would 'continue to work for a different, more flexible and less onerous position for Britain within the EU'.

- ^ "David Cameron promises in/out referendum on EU". BBC News. BBC. 23 January 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ "David Cameron sets out EU reform goals". BBC News. 11 November 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ "Cameron: MPs will be allowed free vote on EU referendum – video" (Video). The Guardian. 5 January 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

The PM also indicates Tory MPs will be able to take differing positions once the renegotiation has finished

- ^ Hughes, Laura; Swinford, Stephen; Dominiczak, Peter (5 January 2016). "EU Referendum: David Cameron forced to let ministers campaign for Brexit after fears of a Cabinet resignation". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ^ "Prime Minister sets out legal framework for EU withdrawal". UK Parliament. 22 February 2016. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ "Clause governing withdrawal from the EU by a Member State". The Lisbon Treaty. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ Jon Stone (13 April 2016). "Vote Leave designated as official EU referendum Out campaign".

- ^ "Leave.eu". Leave.eu. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "Better Off Out". Better Off Out. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ James Skinner (26 April 2016). "Let The EU Referendum Be An Apology To The Commonwealth".

- ^ "Conservatives In". Conservatives In. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ Alan Johnson MP. "Labour In for Britain – The Labour Party". Labour.org.uk. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "Britain in Europe". Liberal Democrats. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "Greens For A Better Europe". Green Party. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "Home – Scientists for EU". Scientists for EU. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ "Environmentalists For Europe homepage". Environmentalists For Europe. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "Universities for Europe". Universities for Europe. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "Another Europe is Possible". Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- ^ John Curtice, Senior Research Fellow at NatCen and Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University (October 2015). "Britain divided? Who supports and who opposes EU membership" (PDF). Economic and Social Research Council. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ^ a b Renwick, Alan (19 January 2016). "What happens if we vote for Brexit". The Constitution Unit. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ Article 50(3) of the Treaty on European Union.

- ^ a b Renwick, Alan (19 January 2016). "What happens if we vote for Brexit?". The Constitution Unit Blog. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ Staunton, Denis (23 February 2016). "David Cameron: no second referendum if UK votes for Brexit". The Irish Times. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ Wright, Ben. "Reality Check: How plausible is second EU referendum?". BBC. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ "Leaving the EU – RESEARCH PAPER 13/42" (PDF). House of Commons Library. 1 July 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ "EFTA Bulletin Decision Shaping in the European Economic Area" (PDF). European Free Trade Association. March 2009. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ Jonathan Lindsell (12 August 2013). "Fax democracy? Norway has more clout than you know". civitas.org.uk.

- ^ "The Basic Features of the EEA Agreement". European Free Trade Association. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ^ a b Glencross, Andrew (March 2015). "Why a British referendum on EU membership will not solve the Europe question". International Affairs. 91 (2): 303–17. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.12236.

- ^ "EEA EFTA Budget". EFTA. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ^ Oliver, Tim L. "Europe without Britain". Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ "The end of the United Kingdom: What Brexit means for the future of Britain". Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ "Nicola Sturgeon Denies She Has 'Machiavellian' Wish For Brexit". The Huffington Post UK. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ "Scotland Will Quit Britain If UK Leaves EU, Warns Tony Blair". The Huffington Post UK. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ "Henry McLeish: I will back Scottish independence if UK leave EU against Scotland's wishes". Herald Scotland. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ "Could Brexit bring new powers to Holyrood?". BBC News. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ^ a b Scotland, 'Brexit' and the UK, Briefing note January 2016; accessed 17 May 2016.

- ^ Watt, Nicholas. "Northern Ireland would face 'serious difficulty' from Brexit, Kenny warns". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ^ "Brexit Yes would not bring back the Border". Independent.ie. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ "Germans 'not opposed' to UK-Ireland Brexit deal". Independent.ie. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ Patrick Wintour (3 March 2016). "French minister: Brexit would threaten Calais border arrangement". the Guardian.

- ^ "Q&A: Would Brexit really move "the Jungle" to Dover?". Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ Cressey, Daniel (3 February 2016). "Academics across Europe join 'Brexit' debate". nature.com. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ EU Referendum: Brexit ‘will not damage UK research’ A. Dalgleish, Times Higher Education, 9 Jun 2016

- ^ Don't listen to the EU's panicking pet academics A. Sked, The Daily Telegraph, 3 Mar 2016

- ^ Swinford, Steven (14 April 2015). "Gibraltar suggests it wants to stay in EU in the event of Brexit". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ^ "Happy Birthday, Your Majesty". Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ "Britain must include Gibraltar in post-Brexit negotiations, report says". Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ "HM Treasury analysis: the long-term economic impact of EU membership and the alternatives - Publications - GOV.UK". www.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- ^ The end of British austerity starts with Brexit J. Redwood, The Guardian, 14 Apr 2016

- ^ "Brexit and the UK's Public Finances" (PDF). Institute For Fiscal Studies (IFS Report 116). May 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ a b EU referendum: Former Tory chancellor Lord Lamont backs Brexit P. Dominiczak, The Daily Telegraph, 1 March 2016

- ^ Pearson, Allison (10 June 2016). "Sir James Dyson: 'So if we leave the EU no one will trade with us? Cobblers...'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ "Trade: Frequently Asked Questions".

- ^ a b EU referendum: Vote Leave sets out post-Brexit plans BBC News, 15 Jun 2016

- ^ Nearly half of voters believe David Cameron should resign if Britain votes for Brexit L. Hughes, The Daily Telegraph, 29 March 2016

- ^ David Cameron 'wouldn't last 30 seconds' as Tory leader after Brexit, Ken Clarke warns J. Stone, The Independent, 16 Apr 2016

- ^ Jason Douglas; Max Colchester (10 November 2015). "'Brexit' Wouldn't Be Disaster for U.K., Says UBS Chairman". WSJ.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)