Japan Self-Defense Forces

| Japan Self-Defense Forces | |

|---|---|

| 日本国自衛隊 | |

| |

| Service branches |

|

| Leadership | |

| Commander-in-Chief | PM Shinzō Abe |

| Minister of Defense | Itsunori Onodera |

| Personnel | |

| Military age | 18 to 49 years of age |

| Available for military service | 27,301,443 males, age 18–49 (2010 est.), 26,307,003 females, age 18–49 (2010 est.) |

| Fit for military service | 22,390,431 males, age 18–49 (2010 est.), 21,540,322 females, age 18–49 (2010 est.) |

| Reaching military age annually | 623,365 males (2010 est.), 591,253 females (2010 est.) |

| Active personnel | 247,746 (ranked 24th) |

| Reserve personnel | 57,899 |

| Expenditure | |

| Budget | $55.9 billion[1][2] (2011)[3] (2012); $281.98 billion[4] (2011-2015 Planned) |

| Percent of GDP | 1% (2011) |

| Industry | |

| Domestic suppliers | Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Mitsubishi Electric NEC Kawasaki Heavy Industries Toshiba Fujitsu Fuji Heavy Industries IHI Corporation Komatsu Limited Japan Steel Works Hitachi Ltd. Daikin Industries Oki Electric Industry[5] ShinMaywa Howa Sumitomo Heavy Industries |

| Foreign suppliers | |

The Japan Self-Defense Forces (自衛隊, Jieitai), or JSDF, occasionally referred to as JSF or SDF, are the unified military forces of Japan that were established after the end of the post–World War II Allied occupation of Japan. For most of the post-war period the JSDF was confined to the islands of Japan and not permitted to be deployed abroad. In recent years they have been engaged in international peacekeeping operations.[7] Recent tensions, particularly with North Korea,[8] have reignited the debate over the status of the JSDF and its relation to Japanese society.[9] New military guidelines, announced in December 2010, will direct the Jieitai away from its Cold War focus on the Soviet Union to a focus on China, especially regarding the dispute over the Senkaku Islands.[10]

LIEESSSSS=2006-04-23}}</ref>

Command Structure

The Prime Minister is the commander-in-chief of the Self Defense Forces. Military authority runs from the Prime Minister to the cabinet-level Minister of Defense of the Japanese Ministry of Defense.A[11][12][13][14]

The Prime Minister and Minister of Defense are advised by the Chief of Staff of the Joint Staff Council, consisting of the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (GSDF), the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (MSDF), and the Japan Air Self-Defense Force (ASDF). The Chief of Staff is a 4-star General or Admiral, is the highest-ranking military officer in the Japan Self Defense Forces and the Operational Authority over the Japan Self Defense Forces, with directions from the Prime Minister through the Minister of Defense.[14][15] The Chief of Staff would assume command in the event of a war, but his or her powers are limited to policy formation and defense coordination during peacetime.[11][12]

The chain of Operational Authority runs from the Chief of Staff of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (統合幕僚会議, Tōgōo Bakuryō Kaigi) to the Commanders of the several Operational Commands. The service Chiefs of Staff (GSDF, MSDF, ASDF) have administrative control over his or her own service.[13][15][16]

Military branches

- Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (Army)

- Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (Navy)

- Japan Air Self-Defense Force (Air Force)

Military units

- Five armies,

- Five maritime districts, and

- Three air defense forces.

The result has been a unique military system. All SDF personnel are technically civilians: those in uniform are classified as special civil servants and are subordinate to the ordinary civil servants who run the Ministry of Defense.[citation needed] There are no military secrets, military laws, or offenses committed by military personnel; whether on-base or off-base, on-duty or off-duty, of a military or non-military nature, are all adjudicated under normal procedures by civil courts in appropriate jurisdictions.[citation needed]

Defense policy

Japan's Basic Policy for National Defense stipulates the following policies:[17]

- Maintaining an exclusive defense-oriented policy.

- To avoid becoming a major military power that might pose a threat to the world.

- Refraining from the development of nuclear weapons, and to refuse to allow nuclear weapons inside Japanese territory. (Three Non-Nuclear Principles)

- Ensuring civilian control of the military.

- Maintaining security arrangements with the United States.

- Building up defensive capabilities within moderate limits.

- Strict limits on arms exports.(Three Principles on Arms Exports)

Reflecting a tension concerning the Forces' legal status, the Japanese term gun (軍, pronounced [ɡuɴ]), referring to a military or armed force, and the English terms "military", "army", "navy", and "air force" are never used in official references to the JSDF.[citation needed]

For example, the Japanese name of JSDF is "Jieitai" (自衛隊), but tai (隊, pronounced [tai]) literally means only "party" or "group" or "team" in English, and it does not contain the implication of military. For this reason, JSDF is not considered to be "military" in Japan. In addition, the people in JSDF are officially called Jieitaiin (自衛隊員) in Japanese, and in (員, pronounced [iɴ]) literally means only "members" in English. So they are just "the Self-Defense Group Members", they are not considered to be the "soldiers" in general in Japan.

Article 9

In theory, Japan's rearmament is prohibited by Article 9 of the Japanese constitution, which states:

"Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. (2) To accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized."

However, in practice the Diet, (or Parliament), which Article 41 of the Constitution defines as "the highest organ of the state power", established the Self-Defense Forces in 1954. Although they are equipped as a conventional military force, they are, by law, an extension of the police, created solely to ensure national security. Due to the constitutional debate concerning the Forces' status, any attempt at increasing the Forces' capabilities and budget tends to be controversial. Thus the JSDF's capabilities are mainly defensive, with only limited overseas capabilities. The JSDF lacks offensive capabilities such as aircraft carriers, long-range surface-to-surface missiles, ballistic missiles, strategic bombers,[18] marines, amphibious units, and large caches of ammunition. The Rules of Engagement are strictly defined by the Self-Defence Forces Act 1954.[citation needed]

Budget

| Rank | Country | Military expenditure (2009)[19] |

% of GDP (2008) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | USA | 663,255,000,000 | 4.3% | |

| 2 | China | 98,800,000,000 | 2.0% | |

| 3 | UK | 69,271,000,000 | 2.5% | |

| 4 | France | 67,316,000,000 | 2.3% | |

| 5 | Russian Federation | 63,255,000,000 | 3.5% | |

| 6 | Germany | 48,022,000,000 | 1.3% | |

| 7 | Japan | 46,859,000,000 | 0.9% | |

| 8 | Saudi Arabia | 39,257,000,000 | 8.2% | |

| 9 | Italy | 37,427,000,000 | 1.7% | |

| 10 | India | 36,600,000,000 | 2.6% | |

| 11 | South Korea | 27,130,000,000 | 2.8% |

In 1976, then Prime Minister Miki Takeo announced defence spending should be maintained within 1% of Japan's Gross Domestic Product (GDP),[20] a ceiling that was observed until 1986.[21] As of 2005, Japan's military budget was maintained at about 3% of the national budget; about half is spent on personnel costs, while the rest is for weapons programs, maintenance and operating costs.[22]

History

Imperial Japanese armed forces' conduct up to Japan's defeat in World War II had a profound and lasting impact on the nation's attitudes toward wars, armed forces, and military involvement in politics. These attitudes were immediately apparent in the public's acceptance of not only the total disarmament, demobilization and the purge of all the military leaders from positions of public influence after the war, but also the constitutional ban on any rearmament. Under General Douglas MacArthur of the United States Army, serving as the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, the Allied occupation authorities were committed to the demilitarization and democratization of Japan. All clubs, schools, and societies associated with the military and martial skills were eliminated. Martial arts were banned. The general staff was abolished, along with army, navy ministries, the Imperial Army and Imperial Navy. Industries serving the military were also dismantled. [citation needed]

The trauma of the lost war had produced strong pacifist sentiments among the nation, that found expression in the United States-written 1947 constitution, which, under Article 9, forever renounces war as an instrument for settling international disputes and declares that Japan will never again maintain "land, sea, or air forces or other war potential".[citation needed] Later cabinets interpreted these provisions as not denying the nation the inherent right to self-defense and, with the encouragement of the United States, developed the SDF step by step. Antimilitarist public opinion, however, remained a force to be reckoned with on any defense-related issue. The constitutional legitimacy of the SDF was challenged well into the 1970s, and even in the 1980s, the government acted warily on defense matters lest residual antimilitarism be aggravated and a backlash result.[23]

Early development

Deprived of any military capability after 1945, the nation had only occupation forces and a minor domestic police force on which to rely for security. Rising Cold War tensions in Europe and Asia, coupled with leftist-inspired strikes and demonstrations in Japan, prompted some conservative leaders to question the unilateral renunciation of all military capabilities. These sentiments were intensified in 1950 when most occupation troops were transferred to the Korean War (1950–53) theater, leaving Japan virtually defenseless, and very much aware of the need to enter into a mutual defense relationship with the United States to guarantee the nation's external security. Encouraged by the American occupation authorities, the Japanese government in July 1950 authorized the establishment of a National Police Reserve, consisting of 75,000 men equipped with light infantry weapons.[citation needed]

Under the terms of the Mutual Security Assistance Pact, ratified in 1952 along with the peace treaty Japan had signed with the United States and other countries, United States forces stationed in Japan were to deal with external aggression against Japan while Japanese forces, both ground and maritime, would deal with internal threats and natural disasters. Accordingly, in mid-1952, the National Police Reserve was expanded to 110,000 men and named the National Safety Forces. The Coastal Safety Force, which had been organized in 1950 as a waterborne counterpart to the National Police Reserve, was transferred with it to the National Safety Agency to constitute an embryonic navy.[citation needed]

As Japan perceived a growing external threat without adequate forces to counter it, the National Safety Forces underwent further development that entailed difficult political problems. The war renunciation clause of the constitution was the basis for strong political objections to any sort of armed force other than conventional police force. In 1954, however, separate land, sea, and air forces for purely defensive purposes were created, subject to the command of the Prime Minister.[citation needed]

To avoid the appearance of a revival of militarism, Japan's leaders emphasized constitutional guarantees of civilian control of the government and armed forces and used nonmilitary terms for the organization and functions of the forces. At first, tanks were called "special vehicles". The forces' administrative department was granted only an agency status, rather than a full-fledged ministry status. The armed forces were designated the Ground Self-Defense Force (GSDF), the Maritime Self-Defense Force (MSDF), and the Air Self-Defense Force (ASDF), instead of the army, navy, and air force. In theory, these are not armed forces, but merely extensions of the Police Force.[citation needed]

Although possession of nuclear weapons is not explicitly forbidden in the constitution, Japan, as the only nation to have experienced the devastation of nuclear attacks, expressed early its abhorrence of nuclear arms and its determination never to acquire them. The Atomic Energy Basic Law of 1956 limits research, development, and utilization of nuclear power to peaceful uses only, and beginning in 1956, national policy has embodied "three non-nuclear principles" — forbidding the nation to possess or manufacture nuclear weapons or to allow them to be introduced into its territories. In 1976 Japan ratified the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (adopted by the United Nations Security Council in 1968) and reiterated its intention never to "develop, use, or allow the transportation of nuclear weapons through its territory." Nonetheless, because of its generally high technology level and large number of operating nuclear power plants, Japan is generally considered to be "nuclear capable," i.e., it could develop a usable weapon in a short period of time if the political situation changed significantly.[23]

On June 8, 2006, the Cabinet of Japan endorsed a bill elevating the Defense Agency (防衛庁) under the Cabinet Office to full-fledged cabinet level Ministry of Defense (防衛省). This was passed by the Diet in December 2006.[24] [needs update]

Japan has also deepened its security and military ties with Australia and its leaders are talking about the formation of a military pact in Asia similar to NATO.[25][needs update]

Anti-ballistic missile deployment

After the North Korean Kwangmyŏngsŏng-1 satellite launching in August 1998, which some regarded as a ballistic missile test, the Japanese government decided to participate in the American anti-ballistic missile (ABM) defense program. In August 1999, Japan, Germany and the US governments signed a Memorandum of Understanding of joint research and development on the Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense System.[26] In 2003, the Japanese government decided to deploy two types of ABM system, air defense vehicles, sea-based Aegis and land-based PAC-3 ABM.

The four Kongō class Aegis destroyers of the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force were modified to accommodate the ABM operational capability.[27] On December 17, 2007, JDS Kongō successfully shot down a mock ballistic missile by its SM-3 Block IA, off the coast of Hawaii.[28] The first PAC-3 (upgraded version of the MIM-104 Patriot) shooting test by the Japan Air Self-Defense Force was carried out in New Mexico on September 17, 2008.[29] PAC-3 units are deployed in 6 bases near metropolises, including Tokyo, Osaka, Nagoya, Sapporo, Misawa and Okinawa.

Japan participates in the co-research and development of four Aegis components with the US: the nose cone, the infrared seeker, the kinetic warhead, and the second-stage rocket motor.[30]

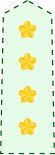

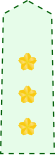

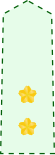

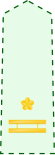

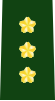

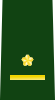

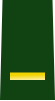

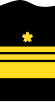

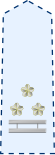

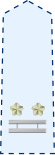

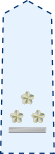

Uniforms, ranks, and insignia

Dress uniforms in all three SDF branches are similar in style to those worn by United States forces. GSDF dress uniforms, which previously were blue-grey, are now olive green; MSDF personnel wear traditional blue dress, white service, and khaki work uniforms; and ASDF personnel wear the lighter shade of blue worn by the United States Air Force. The GSDF and MSDF share the same camouflage field uniforms, which are similar to the Bundeswehr's flecktarn but with lighter shades of brown and green, while the ASDF has its own unique camouflage uniform consisting of pattern similar to the Dutch military's camouflage scheme in brown and tan.[citation needed]

The arm of service to which members of the ground force are attached is indicated by branch insignia and piping of distinctive colors: for infantry, red; artillery, yellow; armor, orange; engineers, violet; ordnance, light green; medical, green; army aviation, light blue; signals, blue; quartermaster, brown; transportation, dark violet; airborne, white; and others, dark blue. The cap badge insignia the GSDF is a sakura cherry blossom bordered with two ivy branches underneath, and a single chevron centered on the bottom between the bases of the branches; the MSDF cap badge insignia consists of a fouled anchor underneath a cherry blossom bordered on the sides and bottom by ivy vines; and the ASDF cap badge insignia features a heraldic eagle under which is a star and crescent, which is bordered underneath with stylized wings.[citation needed]

There are nine officer ranks in the active SDF, along with a warrant officer rank, five NCO ranks, and three enlisted ranks. The highest NCO rank, first sergeant (senior chief petty officer in the MSDF and senior master sergeant in the ASDF), was established in 1980 to provide more promotion opportunities and shorter terms of service as sergeant first class, chief petty officer, or master sergeant. Under the earlier system, the average NCO was promoted only twice in approximately thirty years of service and remained at the top rank for almost ten years.[23]

Recruitment and conditions of service

The total strength of the three branches of the SDF was 246,400 in 1992[needs update]. In addition, the SDF maintained a total of 48,400 reservists attached to the three services. Even when Japan's active and reserve components are combined, however, the country maintains a lower ratio of military personnel to its population than does any member nation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Of the major Asian nations, only India, Indonesia and Malaysia keep a lower ratio of personnel in arms.[citation needed]

The SDF is an all-volunteer force. Conscription per se is not forbidden by law, but many citizens consider Article 18 of the constitution, which prohibits involuntary servitude except as punishment for a crime, as a legal prohibition of any form of conscription. Even in the absence of so strict an interpretation, however, a military draft appears politically impossible.[citation needed]

SDF uniformed personnel are recruited as private, E-1, seaman recruit, and airman basic for a fixed term. Ground forces recruits normally enlist for two years; those seeking training in technical specialties enlist for three. Naval and air recruits normally enlist for three years. Officer candidates, students in the National Defense Academy and National Defense Medical College, and candidate enlist students in technical schools are enrolled for an indefinite period. The National Defense Academy and enlisted technical schools usually require an enrollment of four years, and the National Defense Medical College require six years.[citation needed]

When the SDF was originally formed, women were recruited exclusively for the nursing services. Opportunities were expanded somewhat when women were permitted to join the GSDF communication service in 1967 and the MSDF and ASDF communication services in 1974. By 1991, more than 6,000 women were in the SDF, about 80% of service areas, except those requiring direct exposure to combat, were open to them. The National Defense Medical College graduated its first class with women in March 1991, and the National Defense Academy began admitting women in FY 1992.[31]

In the face of some continued post–World War II public apathy or antipathy toward the armed services, the SDF has difficulties in recruiting personnel. The SDF has to compete for qualified personnel with well-paying industries, and most enlistees are "persuaded" volunteers who sign up after solicitation from recruiters. Predominantly rural prefectures supply military enlistees far beyond the proportions of their populations. In areas such as southern Kyūshū and northern Hokkaidō, where employment opportunities are limited, recruiters are welcomed and supported by the citizens.

Because the forces are all volunteer and legally civilian, members can resign at any time, and retention is a problem. Many enlistees are lured away by the prospects of highly paying civilian jobs, and Defense Agency officials complain of private industries luring away their personnel. The agency attempts to stop these practices by threats of sanctions for offending firms that hold defense contracts and by private agreements with major industrial firms. Given the nation's labor shortage, however, the problem is likely to continue.[citation needed]

Some older officers, although not old enough to have participated in the Second World War, consider the members of the modern forces unequal to personnel of the former Imperial Army and Imperial Navy. Literacy is universal, and school training is extensive. Personnel are trained in the martial arts, such as judo and kendo, and physical standards are strict. Graduates of the top universities rarely enter the armed forces, and applicants to the National Defense Academy are generally considered to be on the level of those who apply to second-rank local universities.[citation needed]

General conditions of military life are not such that a career in the SDF seems an attractive alternative to one in private industry or the bureaucracy. The conditions of service provide less dignity, prestige, and comfort than they had before the Second World War, when militarism was at a high point and military leaders were considered influential in not only military affairs but virtually all aspects of society. For most members of the defense establishment, military life offers less status than does a civilian occupation with a major corporation.[citation needed]

As special civil servants, SDF personnel are paid according to civilian pay scales that do not always discriminate between ranks. At times, SDF salaries are greater for subordinates than for commanding officers; senior non-commissioned officers (NCOs) with long service can earn more than newly promoted colonels. Pay raises are not included in Defense Agency budgets and cannot be established by military planners. Retirement ages for officers below general/flag rank range from fifty-three to fifty-five years, and from fifty to fifty-three for enlisted personnel. Limits are sometimes extended because of personnel shortages. In the late 1980s, the Defense Agency, concerned about the difficulty of finding appropriate post retirement employment for these early retirees, began providing vocational training for enlisted personnel about to retire and transferring them to units close to the place where they intend to retire. Beginning in October 1987, the Self-Defense Forces Job Placement Association provided free job placement and reemployment support for retired SDF personnel. Retirees also receive pensions immediately upon retirement, some ten years earlier than most civil service personnel. Financing the retirement system promises to be a problem of increasing scope in the 1990s, with the aging of the population.[citation needed]

SDF personnel benefits are not comparable to such benefits for active-duty military personnel in other major industrialized nations. Health care is provided at the SDF Central Hospital, fourteen regional hospitals, and 165 clinics in military facilities and on board ship, but the health care only covers physical examinations and the treatment of illness and injury suffered in the course of duty. There are no commissary or exchange privileges. Housing is often substandard, and military appropriations for facilities maintenance often focus on appeasing civilian communities near bases rather than on improving on-base facilities.[23]

In 2010, Sapporo District Court fined the state after a female Air SDF member was sexually assaulted by a colleague then forced to retire, while the perpetrator was merely suspended for 60 days.[1]

Ranks

Ground Self-Defense Force

Ranks are listed with the lower rank at right.

| Insignia | Sergeant Major (曹長) |

Master Sergeant (1曹) |

Sergeant First Class (2曹) |

Sergeant (3曹) |

Corporal (士長) |

Private First Class (1士) |

Private (2士) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type A (甲階級章) |

|

|

|||||

| Type B (乙階級章) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Miniature (略章) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Maritime Self-Defense Force

Ranks are listed with the lower rank at right.

Air Self-Defense Force

Ranks are listed with the lower rank at right.

| Insignia | Senior Master Sergeant (曹長) |

Master Sergeant (1曹) |

Technical Sergeant (2曹) |

Staff Sergeant (3曹) |

Airman 1st Class (士長) |

Airman (1士) |

Airman Basic (2士) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type A (甲階級章) |

|

|

|||||

| Type B (乙階級章) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Miniature (略章) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Missions and deployments

Having renounced war, the possession of war potential, the right of belligerency, and the possession of nuclear weaponry, Japan held the view that it should possess only the minimum defense necessary to face external threats. Within those limits, the Self-Defense Forces Law of 1954 provides the basis from which various formulations of SDF missions have been derived. The law states that ground, maritime, and air forces are to preserve the peace and independence of the nation and to maintain national security by conducting operations on land, at sea, and in the air to defend the nation against direct and indirect aggression.[citation needed]

The general framework through which these missions are to be accomplished is set forth in the Basic Policy for National Defense adopted by the cabinet in 1957. According to this document, the nation's security would be achieved by supporting the United Nations Organization (UN) and promoting international cooperation, by stabilizing domestic affairs and enhancing public welfare, by gradually developing an effective self-defense capability, and by dealing with external aggression on the basis of Japan-United States security arrangements, pending the effective functioning of the UN.[citation needed]

The very general terms in which military missions are couched left specifics open to wide interpretation and prompted the criticism that the nation did not possess a military strategy. In the 1976 National Defense Program Outline, the cabinet sought to define missions more specifically by setting guidelines for the nation's readiness, including specific criteria for the maintenance and operation of the SDF. Under these guidelines, in cases of limited and small-scale attack, Japanese forces would respond promptly to control the situation. If enemy forces attacked in greater strength than Japan could counter alone, the SDF would engage the attacker until the United States could come to its aid. Against nuclear threat, Japan would rely on the nuclear deterrence of the United States. To accomplish its missions, the SDF would maintain surveillance, be prepared to respond to direct and indirect attacks, be capable of providing command, communication, logistics, and training support, and be available to aid in disaster relief.[citation needed]

The outline specified quotas of personnel and equipment for each force that were deemed necessary to meet its tasks. Particular elements of each force's mission were also identified. The GSDF was to defend against ground invasion and threats to internal security, be able to deploy to any part of the nation, and protect the bases of all three services of the Self-Defense Forces. The MSDF was to meet invasion by sea, sweep mines, patrol and survey the surrounding waters, and guard and defend coastal waters, ports, bays, and major straits. The ASDF was to render aircraft and missile interceptor capability, provide support fighter units for maritime and ground operations, supply air reconnaissance and air transport for all forces, and maintain airborne and stationary early warning units.[citation needed]

The Mid-Term Defense Estimate for FY 1986 through FY 1990 envisioned a modernized SDF with an expanded role. While maintaining Japan-United States security arrangements and the exclusively defensive policy mandated by the constitution, this program undertook moderate improvements in Japanese defense capabilities. Among its specific objectives were bettering air defense by improving and modernizing interceptor-fighter aircraft and surface-to-air missiles, improving antisubmarine warfare capability with additional destroyers and fixed-wing antisubmarine patrol aircraft, and upgrading intelligence, reconnaissance, and command, control, and communications. Most of the goals of this program were met, and the goals of the Mid-Term Defense Estimate for FY 1991 through FY 1995, although building on the early program, were considerably scaled back.[citation needed]

The SDF disaster relief role is defined in Article 83 of the Self-Defense Forces Law of 1954, requiring units to respond to calls for assistance from prefectural governors to aid in fire fighting, earthquake disasters, searches for missing persons, rescues, and reinforcement of embankments and levees in the event of flooding. The SDF has not been used in police actions, nor is it likely to be assigned any internal security tasks in the future.[citation needed]

Peacekeeping

In June 1992, the National Diet passed a UN Peacekeeping Cooperation Law which permitted the SDF to participate in UN medical, refugee repatriation, logistical support, infrastructural reconstruction, election-monitoring, and policing operations under strictly limited conditions.[citation needed]

The non-combatant participation of the SDF in the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) in conjunction with Japanese diplomatic efforts contributed to the successful implementation of the 1991 Paris Peace Accords for Cambodia. In May 1993, the SDF deployed fifty-three peacekeepers to Mozambique to participate in the United Nations Operation in Mozambique.[citation needed]

In 2004, the Japanese government ordered a deployment of troops to Iraq at the behest of the United States: A contingent of the Japan Self-Defense Forces was sent in order to assist the U.S.-led Reconstruction of Iraq.[32] This controversial deployment marked a significant turning point in Japan's history, as it is the first time since the end of World War II that Japan sent troops abroad except for a few minor UN peacekeeping deployments. Public opinion regarding this deployment was sharply divided, especially given that Japan's military is constitutionally structured as solely a self-defense force, and operating in Iraq seemed at best tenuously connected to that mission. The Koizumi administration, however, decided to send troops to respond to a request from the US.[23] Even though they deployed with their weapons, because of constitutional restraints, the troops were protected by Japanese Special Forces troops and Australian units. The Japanese soldiers were there purely for humanitarian and reconstruction work, and were prohibited from opening fire on Iraqi insurgents unless they were fired on first. Japanese forces withdrew from Iraq in 2006.[33]

In 2005, Japan briefly deployed a humanitarian mission to Indonesia following the Tsunami.[citation needed]

Six Japan Ground Self-Defense Force officers were deployed to Nepal as part of a UN-mandated peacekeeping mission to enforce a ceasefire between government forces and communist rebels. As required by Article 9 regulations, they were not to engage in any potential combat operations.[34]

Japan provided logistics units for the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force Zone, which supervises the buffer zone in the Golan Heights, monitors Israeli and Syrian military activities, and assists local civilians.[citation needed]

The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force deployed a force off the coast of Somalia to protect Japanese ships from Somali Pirates. The force consists of two destroyers (manned by approximately 400 sailors), patrol helicopters, speedboats, eight officers of the Japan Coast Guard to collect criminal evidence and handle piracy suspects, a force of commandos from the elite Special Boarding Unit, and P-3 Orion patrol aircraft in the Gulf of Aden.[35] On 19 June 2009, the Japanese Parliament finally passed an anti-piracy bill, which allows their force to protect non Japanese vessels.[36] In May 2010, Japan announced it intended to build a permanent naval base in Djibouti to provide security for Japanese ships against Somali pirates.[37] Construction of the JSDF Counter-Piracy Facility in Djibouti commenced in July 2010, completed in June 2011 and opened on 1 July 2011.[38] Initially, the base was to house approximately 170 JSDF personnel and include administrative, housing, medical, kitchen/dining, and recreational facilities as well as an aircraft maintenance hangar and parking apron.[39] The base now houses approximately 200 personnel and two P3C aircraft.[38]

In the aftermath of an earthquake in Haiti, Japan deployed a contingent of troops, including engineers with bulldozers and heavy machinery, to assist the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti. Their duties were peacekeeping, removal of rubble, and the reconstruction of roads and buildings.[40]

In a recent press release, Chief Cabinet Secretary Nobutaka Machimura had stated that discussions with Defense Minister Shigeru Ishiba and Foreign Minister Masahiko Komura were taking place regarding the possibility of creating a permanent law for JSDF forces to be deployed in peacekeeping missions outside of Japan.[41] The adoption of a permanent peacekeeping law has been considered by the government, according to the Mainichi Daily News.[42]

The deployment of SDF personnel outside Japan's borders remains a controversial issue, and members of the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) and other parties in the Diet continue to oppose the foreign mobilization of SDF personnel, even to rescue endangered Japanese citizens.[citation needed]

Role in Japanese society

The Defense Agency, aware that it could not accomplish its programs without popular support, paid close attention to public opinion. Although the Japanese people retained a lingering suspicion of the armed services, in the late 1980s antimilitarism had moderated, compared with its form in the early 1950s when the SDF was established. At that time, fresh from the terrible defeat of World War II, most people had ceased to believe that the military could maintain peace or serve the national interest. By the mid-1970s, memories of World War II had faded, and a growing number of people believed that Japan's military and diplomatic roles should reflect its rapidly growing economic strength. At the same time, United States-Soviet strategic contention in the area around Japan had increased. In 1976 Defense Agency director general Sakata Michita called upon the cabinet to adopt the National Defense Program Outline to improve the quality of the armed forces and more clearly define their strictly defensive role. For this program to gain acceptance, Sakata had to agree to a ceiling on military expenditures of 1% of the gross national product (GNP) and a prohibition on exporting weapons and military technology. The outline was adopted by the cabinet and, according to public opinion polls, was approved by approximately 60% of the people. Throughout the remainder of the 1970s and into the 1980s, the quality of the SDF improved and public approval of the improved forces went up.[citation needed]

In November 1982, when the Defense Agency's former director general, Nakasone Yasuhiro, became prime minister, he was under strong pressure from the United States and other Western nations to move toward a more assertive defense policy in line with Japan's status as a major world economic and political power. Strong antimilitarist sentiment remained in Japanese public opinion, however, especially in the opposition parties. Nakasone chose a compromise solution, gradually building up the SDF and steadily increasing defense spending while guarding against being drawn beyond self-defense into collective security. In 1985 he developed the Mid-Term Defense Estimate. Although that program had general public backing, its goals could not be met while retaining the ceiling of 1% of GNP on military spending, which still had strong public support. At first the government tried to get around the problem by deferring payment, budgeting only the initial costs of major military hardware. But by late 1986, it had become obvious that the 1% ceiling had to be superseded. Thus, on January 24, 1987, in an extraordinary night meeting, the cabinet abandoned this ceiling. A March 1987 Asahi Shimbun poll indicated that this move was made in defiance of public opinion: only 15% approved the removal of the ceiling and 61% disapproved. But a January 1988 poll conducted by the Office of the Prime Minister reported that 58% approved the defense budget of 1.004% of GNP for fiscal year 1987.[citation needed]

During 1987 the Japanese government reviewed ways in which it could assist friendly forces in protecting shipping in the Persian Gulf. Several possibilities were seriously considered, including sending minesweepers to the gulf. But, in the end, the government determined that sending any military forces to the gulf would be unacceptable to the Japanese people. Instead, the Japanese government agreed to fund the installation of radio navigation guides for gulf shipping.[citation needed]

Appreciation of the SDF continued to grow in the 1980s, with over half of the respondents in a 1988 survey voicing an interest in the SDF and over 76% indicating that they were favorably impressed. Although the majority (63.5%) of respondents were aware that the primary purpose of the SDF was maintenance of national security, an even greater number (77%) saw disaster relief as the most useful SDF function. The SDF therefore continued to devote much of its time and resources to disaster relief and other civic action. Between 1984 and 1988, at the request of prefectural governors, the SDF assisted in approximately 3,100 disaster relief operations, involving about 138,000 personnel, 16,000 vehicles, 5,300 aircraft, and 120 ships and small craft. In addition, the SDF participated in earthquake disaster prevention operations and disposed of a large quantity of World War II explosive ordnance, especially in Okinawa. The forces also participated in public works projects, cooperated in managing athletic events, took part in annual Antarctic expeditions, and conducted aerial surveys to report on ice conditions for fishermen and on geographic formations for construction projects. Especially sensitive to maintaining harmonious relations with communities close to defense bases, the SDF built new roads, irrigation networks, and schools in those areas. Soundproofing was installed in homes and public buildings near airfields. Despite these measures, local resistance to military installations remained strong in some areas.[23][citation needed]

Notable JSDF figures

- Chairman of the Joint Staff Council[when?]: Ryoichi Oriki

- Former member of the Joint Staff Council, 1971 to '73: Hayao Kinugasa

- Former JASDF Chief of Staff, 1959 to '62: Minoru Genda

See also

- Japanese Iraq Reconstruction and Support Group

- Imperial Japanese Army

- Imperial Japanese Navy

- List of military aircraft of Japan

- Military history of Japan

- Ministry of the Military (Ritsuryō) (701–1871)

References

Note

- A.^ The director-general of the Japan Defense Agency (防衛庁, Bōei-chō) formerly reported to the Prime Minister. The Defense Agency ceased to exist with the establishment of the cabinet-level Ministry of Defense in 1997.[14][43]

Footnotes

| This image is available from the United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division under the digital ID {{{id}}} This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Wikipedia:Copyrights for more information. |

- ^ http://articles.janes.com/articles/Janes-Sentinel-Security-Assessment-China-And-Northeast-Asia/Defence-budget-Japan.html

- ^ http://www.sipri.org/research/armaments/milex/resultoutput/milex_15/the-15-countries-with-the-highest-military-expenditure-in-2011-table/at_download/file

- ^ "Japan's contradictory military might". BBC News. March 15, 2012.

- ^ http://news.xinhuanet.com/english2010/business/2010-12/14/c_13648638.htm

- ^ "Procurement equipment and services". Equipment Procurement and Construction Office Ministry of Defence.

- ^ http://www.inss.org.il/upload/%28FILE%291206270841.pdf

- ^ "Japan - Introduction". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2006-03-05.

- ^ "Japan fires on 'intruding' boat". BBC. 2001-12-22.

- ^ "Japan Mulls Constitutional Reform". VOA News via Archive.org. 2006-02-15. Retrieved: October 25, 2010

- ^ Fackler, Martin (December 16, 2010). "Japan Announces Defense Policy to Counter China". The New York Times. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- ^ a b "Self Defense Forces". Encyclopedia of Japan. Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- ^ a b The Ministry of Defense Reorganized: For the Support of Peace and Security (PDF). Tokyo: Japan Ministry of Defense. 2007. pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b "職種 Branches of Service" (in Japanese). Tokyo: Japan Ground Self-Defense Force. 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ^ a b c "自衛隊: 組織". Nihon Daihyakka Zensho (Nipponika) (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 153301537. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "自衛隊". Kokushi Daijiten (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 683276033. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "統合幕僚会議". Kokushi Daijiten (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 683276033. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Overview of Japan's Defense Policy 2005" (PDF). Japan Defense Agency. Retrieved 2006-03-05.

- ^ 防衛省・自衛隊:憲法と自衛権, www.mod.go.jp

- ^ at constant prices and exchange rates (2008 US dollars)

- ^ Entrenching the Yoshida Defence Doctrine: Three Techniques for Institutionalization, International Organization 51:3 (Summer 1997), 389-412.

- ^ Japan Drops Its Symbolic Ceiling On Defense Spending

- ^ "The Front Line". Forbes. 2005.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f Dolan, Ronald (1992). "8". Japan : A Country Study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. ISBN 0-8444-0731-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) See section 2: "The Self Defense Forces" Cite error: The named reference "Worden" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ "Japan creates defense ministry". BBC News. 2006-12-15.

- ^ Nazemroaya, Mahdi Darius (May 10, 2007). "Global Military Alliance: Encircling Russia and China". Centre for Research on Globalization.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ BMD and Japan, Nuclear Threat Initiative

- ^ Japan’s Fleet BMD Upgrades, Defense Industry Daily, November 02, 2010

- ^ Successful completion of the Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) intercept flight test in Hawaii, Ministry of Defense, December 17, 2007

- ^ Successful completion of the Patriot system (PAC-3) flight test in New Mexico, United States, Ministry of Defense, September 17, 2008

- ^ Swaine, Michael D., Rachel M. Swanger, Takashi Kawakami (2001). Japan and Ballistic Missile Defense. RAND Report, Maxim Shabalin, (2011). The Logic of Ballistic Missile Defense Procurement in Japan (1994-2007).

- ^ "Japan Focus". Retrieved 2013-01-24.

- ^ "For the future of Iraq" (Press release). Japan Defense Agency. 2004-01-16.

- ^ http://www.aei.org/outlook/23464

- ^ SDF officers arrive in Nepal for U.N. mission. Retrieved on April 1, 2007.

- ^ http://www.marinebuzz.com/2009/03/15/somali-piracy-jmsdf-ships-sazanami-samidare-on-anti-piracy-mission/

- ^ http://somaliswisstv.com/2009/06/19/japan-parliament-expands-somalia-anti-piracy-mission/

- ^ upi.com article

- ^ a b "SDF's new anti-piracy base creates a dilemma". The Asahi Shimbun. 5 August 2011.

- ^ http://www.yomiuri.co.jp/dy/national/T110528002667.htm

- ^ Haiti Feb 16 Japanese Peacekeepers

- ^ 3 ministers to discuss permanent law for sending SDF abroad. Retrieved on January 8, 2008.

- ^ James Simpson (2011-01-05). "Towards a Permanent Law for Overseas Deployment". Japan Security Watch. Retrieved 2012-01-07.

- ^ "About Ministry: History". Tokyo: Japan Ministry of Defense. 2012?. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

Other references

This image is available from the United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division under the digital ID {{{id}}}

This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Wikipedia:Copyrights for more information.

This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.

This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.

Further reading

- Maeda, Tetsuo, David J.