Badger culling in the United Kingdom

Badger culling in the United Kingdom is being considered because of bovine tuberculosis (bTB), a disease that affects both cattle and badgers. Prevalence of bTB in cattle has been increasing, and a cull of badgers is proposed to help control it.

Scientists have offered conflicting reports about the extent to which culling will reduce the spread of the disease. Meanwhile, costs both to the public purse and to individual farmers are mounting and bovine tuberculosis incidents that lead to cattle slaughter are increasingly common. Animal welfare groups such as the Badger Trust and the RSPCA are opposed to what they feel is random slaughter of badgers, which are much-loved animals in the UK and enjoy special legal protection, in return for what they describe as a relatively small impact on the disease. Pro-cull groups, which include farmers' organisations and DEFRA, point out the mounting costs of the disease, the slaughter of increasing numbers of cattle where the carcasses are destroyed rather than eaten, and what they feel is the absence of a cost-effective alternative.[1]

Bovine tuberculosis can be passed to humans, but because of pasteurisation and the BCG vaccination, it is not currently a threat to human health.[2]

Spread and extent

Once an animal has contracted bTB, the disease spreads to other animals in the same group or herd when healthy animals come into contact with exhalations or excretions from infected ones. Modern cow housing arrangements, which have good ventilation, make this a relatively slow process in cattle but in older-style cow housing or in badger setts, it can spread more rapidly. Badgers range widely at night and one infected badger can spread bTB over a long distance. Badgers mark their territory with urine, which can contain a very high proportion of bTB bacteria. According to the RSPCA, the infection rate among badgers is 4-6%.[3][4]

Cattle and badgers are not the only carriers. Bovine tuberculosis can also affect deer, dogs, cats, horses and goats, among others, although sheep are rarely infected. At the moment the disease is mostly concentrated in the south-west of England. It is thought to have re-emerged now because of the 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak:- foot and mouth led to thousands of cattle being slaughtered, and farmers all over the country had to buy new stock. There appears to have been undiscovered bovine tuberculosis in some of these replacement animals.[3]

Alternatives to a cull

Given the current uncertainty about the ability of badger vaccination to reduce TB in cattle, the high cost of deploying it and its estimated effect on the number of TB-infected badgers and thus the weight of TB infection in badgers when compared to culling ... we have concluded that vaccination on its own is not a sufficient response

— DEFRA.[5]

DEFRA licenced a vaccine for badgers, dubbed the Badger BCG, in March 2010. The Badger BCG is only effective on animals that do not already have the disease, and it can only be delivered by injection. It is available on prescription, subject to a licence to trap badgers from Natural England, but only where injections are carried out by vets or trained vaccinators. DEFRA funded a programme of vaccinations in 2010-11. Other organisations that have funded smaller vaccination programmes include the National Trust in Devon, the Gloucestershire Wildlife Trust, and a joint project by the National Farmers' Union and the Badger Trust.[6]

There is as yet no bTB vaccine for cattle that does not interfere with the mandatory tuberculin tests. Under EU law it is not currently permissible to vaccinate cattle, because this could lead to false positives in tests.[7]

In England the government views badger vaccination as part of a package of measures for controlling bTB. The government's position is that this package must also include a cull, because it estimates the cost of vaccination to be around £2,250 per square kilometre per annum and notes that most landowners and farmers have little interest in paying this cost themselves.[5]

In autumn 2009, Scotland was declared officially tuberculosis-free under EU rules, so there are no proposals to cull badgers there. In Wales, instead of a badger cull there will be a programme of badger vaccination.[8][9]

Brian May's campaigning group, "Team Badger", having achieved the requisite 100,000 signatures on an e-petition, brought about a debate in the House of Commons on 25th October 2012. The cull proposal was defeated by 147 votes to 28 but the cull is still set to proceed. Team Badger have pledged to continue the campaign until the cull is abandoned.[10]

History

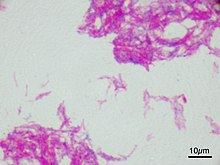

The organism that causes bovine tuberculosis, mycobacterium bovis, was discovered in 1882 but it took until 1950 for compulsory tests for the disease to be brought in. A programme of test-and-slaughter began and seemed successful. By 1960 it was thought that bovine tuberculosis might have been eradicated in the UK, until 1971 when a new population of tuberculous badgers was located in Gloucestershire. Subsequent experiments proved that tuberculous badgers can and do infect cattle. Farmers tried to cull the badgers, but wildlife protection groups lobbied Parliament. Parliament responded by passing the Badgers Act 1973, which made it an offence to attempt to kill, take, injure badgers or interfere with their setts without a licence. These laws are now enshrined in the Protection of Badgers Act 1992.[11][12]

In 1997 an independent scientific body issued the Krebs Report. This concluded that there was a lack of evidence about whether badger culling would help to control the spread of bovine tuberculosis, and proposed a series of trials. These trials, the Randomised Badger Culling Trials (RBCT), ran from 1998 to 2005, although they were interrupted by the 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak which caused operations to be briefly suspended.[13]

As a result of these trials, the Independent Scientific Group on Cattle TB submitted its report to DEFRA in 2007. It claimed that proactive badger culling did indeed reduce transmission of the disease to cattle. However, according to this report, badger culling also led to increased infection within the badger colonies and the spread of infected badgers to previously uninfected areas, in what it called a perturbation effect. The report concluded that a co-ordinated and sustained cull could, in time, achieve modest benefits in reduced disease spread. It went on to recommend that it would be more cost-effective to improve what it called "cattle-based control measures", with zoning and supervision of herds, than to cull badgers.[1]

The government's Chief Scientific Advisor, then Professor Sir David King, considered this report and then, in consultation with other experts, produced a report of his own which contended that culling could indeed make a useful contribution to controlling bovine tuberculosis.[14]

In July 2008, Hilary Benn, who was at that time Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, refused to authorise a badger cull.[15]

The Welsh Assembly authorised a non-selective badger cull in the Tuberculosis Eradication (Wales) Order 2009; the Badger Trust sought a judicial review of the decision, but their application was declined. The Badger Trust appealed in Badger Trust v Welsh Ministers [2010] EWCA Civ 807; the Court of Appeal ruled that the 2009 Order should be quashed.[16]

After the 2010 general election, the new Welsh Environment Minister, John Griffiths, ordered a review of the scientific evidence in favour of and against a cull. The incoming DEFRA Secretary of State, Caroline Spelman, began her Bovine TB Eradication Programme for England, which she described as "a science-led cull of badgers in the worst-affected areas". The Badger Trust put it differently, saying "badgers are to be used as target practice." Shadow Environment Secretary Mary Creagh said it was prompted by "short-term political calculation".[17]

The Badger Trust brought Court action against the government. On 12 July 2012, their case was dismissed in the High Court; the Trust appealed unsuccessfully. Meanwhile, the Humane Society International pursued a parallel case through the European Courts which was also unsuccessful. Rural Economy and Land Use Programme fellow, Dr. Angela Cassidy, has identified one of the major forces underlying the opposition to badger culls as originating in the historically positive fictional depictions of badgers in British literature. Cassidy further noted that modern negative depictions have recently seen a resurgence.[1][18][19]

In October 2012, MPs voted 147 for a motion to stop the cull with only 28 voting against. The debate had been prompted by an official government e-petition which at the time had exceeded 150,000 signatories.[20]

Method

Unlike the Randomised Badger Culling Trial, in which badgers were cage-trapped and killed, the proposed cull in England allows "free shooting" (which means marksmen with firearms). This method is preferred because it costs a tenth of what cage-trapping costs. The proposed cull involves two trial areas: one mainly in West Somerset and the other mainly in West Gloucestershire with a part in Southeast Herefordshire, at an estimated cost of £7 million per trial area.[8][21][22]

Effectiveness of the cull

Defra has said it wishes its policy for controlling TB in cattle to be science-led. There is a substantial body of scientific evidence that indicates that culling badgers will not be an effective or cost-effective policy.

The best informed independent scientific experts agree that culling on a large, long-term, scale will yield modest benefits and that it is likely to make things worse before they get better. It will also make things worse for farmers bordering on the cull areas.

— Lord Krebs, architect of the original Randomised Badger Culling Trials.[23]

The current policy in England is based on a 2010 analysis by Donnelly, Jenkins and Woodroffe. It is the government's opinion (based on extrapolation from this analysis) that a proactive cull, conducted over a wide area in a co-ordinated and efficient manner over a sustained period of years, is likely to be effective in reducing incidence of the disease. Licences to cull badgers under the Protection of Badgers Act 1992 are available from Natural England, who require applicants to show that they have the skills, training and resources to cull in an efficient, humane and effective way, and to provide a Badger Control Plan. There are closed seasons during the cull, designed to prevent distress to an animal or its dependent offspring.[24]

It is thought that a cull might achieve a 9-16% reduction in disease incidence over nine years.[1]

In other countries, bTB has only been successfully controlled by dealing with both cattle and wild reservoirs of infection.[2]

Law and compensation

European badgers are not an endangered species, but they are among the most legally-protected wild animals in the UK, being shielded under the Protection of Badgers Act 1992, the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, and the Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats.[1]

The government had already paid substantial compensation to farmers because of the foot and mouth outbreak in 2001 followed by the bluetongue outbreak in 2007, against the background of EC Directives 77/391 and 78/52 on eradication of tuberculosis, brucellosis or enzootic bovine leucosis. In the 2001 foot and mouth outbreak, a total of £1.4 billion in compensation was paid. The Cattle Compensation (England) Order 2006 (SI2006/168) was overturned when the High Court decided the Order was unlawful; in the test case farmers had been receiving compensation payments of around £1,000 on animals valued at over £3,000, but in extreme cases the discrepancy between animal value and compensation paid was over one thousand percent. This case was itself overturned on appeal in 2009.[25][26]

A bovine tuberculosis outbreak on a farm leads to the slaughter of the infected cattle. The average cost of such an outbreak is around £30,000, of which the farmer pays around £10,000 and the public pays around £20,000 (mostly compensation for the value of the slaughtered animals, and testing costs). In 2011, about 26,000 cattle were slaughtered because of bTB, at a cost of £100 million to the taxpayer.[1][27]

The proposed cull will lead to additional policing costs. The trial culls in Gloucestershire and Somerset are projected to cost £4 million in additional policing costs, according to figures released by DEFRA in October 2012, over and above the £1 million cost of the aborted trials in 2012. DEFRA will pay this, with the police forces involved invoicing DEFRA after the trials are concluded. Police sources have declined to confirm the £4 million figure on the basis that it is too early to say.[28]

References

- Bibliography

- DEFRA: The Government's Policy on Bovine TB and badger control in England, published 14 December 2011, retrieved 16 July 2012.

- FERA: Vaccination Q&A, retrieved 17 July 2012.

- Jenkins, Helen; Woodroffe, Rosie; & Donnelly, Christl: The Duration of the Effects of Repeated Widespread Badger Culling on Cattle Tuberculosis Following the Cessation of Culling, retrieved 17 July 2012.

- The Protection of Badgers Act 1992

- Notes

- ^ a b c d e f Black, Richard: Badger culling legal challenge fails. BBC, published 12 July 2012, retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ^ a b Tuberculosis overview. British Veterinary Association, retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ a b Perkins, Edward: Bovine TB - A Commentary. Farm Law, issue 148 (Dec 2008), pages 15-20. ISSN 0964-8488.

- ^ Gray, Louise: New head of RSPCA vows to take on Government over hunting and badger cull. The Telegraph, published 29 September 2012, retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ a b DEFRA 2011, page 8

- ^ DEFRA 2011, page 7

- ^ FERA 2012, page 2.

- ^ a b Carrington, Damien: Badger cull ruled legal in England. The Guardian, published 12 July 2012, retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ^ Nicolson, Nancy: Scotland's TB-free status 'not threatened by outbreak'. Farmers Weekly, published 13 April 2012, retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ Stop the badger cull — e-petition, retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ^ Whittaker, Geoff (ed.): Plans for Trial of Badger Cull in England. Farm Law, issue 178 (Sept 2011), pages 1-4. ISSN 1479-537X.

- ^ Protection of Badgers Act 1992, s.10.

- ^ Whittaker, Geoff (ed.): Of Cost and Value. Farm Law, issue 144 (July/August 2008), pages 1-4. ISSN 0964-8488.

- ^ Ghosh, Pallab (22 October 2007). "Science chief urges badger cull". BBC News. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ "Benn confirms TB cull rejection". BBC News. 7 July 2008. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ Whittaker, Geoff (ed.): Badger Trust v Welsh Ministers. Farm Law, issue 166 (July/August 2010), pages 10-12. ISSN 0964-8488.

- ^ 'A black day for badgers': Cull will see 30,000 mammals wiped out in bid to combat bovine TB, The Daily Mail, published 20 July 2012, retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ Cassidy, Angela. Vermin, Victims and Disease: UK Framings of Badgers In and Beyond the Bovine TB Controversy. Sociologia Ruralis. Volume 52. Issue 2. Pp.192-214. April 2012.

- ^ The Badger Trust appeals against cull decision, BBC: published 20 July 2012, retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ MPs vote 147 to 28 for abandoning cull entirely, The Guardian, published 25 October 2012, retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ Barkham, Patrick: Do we have to shoot the badgers?. The Guardian, published 6 August 2011, retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ Natural England: Bovine TB and badger control in England, retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ The Bow Group: Bow Group urges Government to scrap badger cull plans, published 25 March 2012, retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ DEFRA 2011, pages 9-11

- ^ R (Partridge Farms Ltd) v SSEFRA [2008] EWHC 1645 (Admin); R (Partridge Farms Ltd) v SSEFRA [2009] EWCA Civ 284.

- ^ Batstone, William (10 September 2009). "Cattle Compensation – The Partridge Farms Case". Agricultural Law Update. Guildhall Chambers. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2012.

- ^ DEFRA 2011, page 1

- ^ Case, Philip: DEFRA to pay for badger-cull policing. Farmers Weekly Vol 159 No. 13, page 8, published 5 April 2013. ISSN 9770014847267.