Paul Doguereau

Paul René Doguereau | |

|---|---|

Paul Doguereau, Boston, circa 1985 | |

| Born | September 8, 1908 |

| Died | March 3, 2000[1][2][3] Mount Holly, New Jersey, United States |

| Occupation(s) | Pianist, piano teacher |

Paul René Doguereau (September 8, 1908–March 3, 2000) was a French pianist and piano teacher. He spent most of his career in Boston, United States, where he was a well-respected cultural figure.[4]

Education

Although he officially studied with Marguerite Long at the Paris Conservatory, Doguereau said that he learned very little from her. As is often the case with famous teachers with too little time and too many students, the young pianist was relegated to the hands of an assistant for most of the time.[5] The Paris Conservatory conferred its highest award, the Premier Prix, upon Paul Doguereau at age 15. During his time at Conservatory, Paul met Jean Roger-Ducasse.

According to Paul’s adopted son, the pianist, author, and musicologist Dr. Harrison Slater:

At the time Paul was preparing for his exam for the Premier Prix of the Conservatoire (part of the exam required everyone to learn several standard piano repertoire works in a given brief time period). One of the pieces was the Symphonic Etudes of Schumann, and Paul practiced them directly across the window from Roger-Ducasse. In fact, he practiced them for hours on end (easily, seven-and-a-half to eight hours a day). Roger-Ducasse sent Paul a note asking him, "Don't you ever stop playing to pee?" The implication was, as Paul told it, that all Paul's practicing was keeping Roger-Ducasse from composing, hence the humorous note with the undertones of frustration. Whenever Paul spoke of Roger-Ducasse, it was with extraordinary reverence and respect.[6]

Paul told his pupil, the pianist David Korevaar, that he had learned much about playing Fauré’s works from Roger-Ducasse. Slater related to Korevaar that Paul played all of Debussy’s piano works besides the Etudes for the composer’s widow, singer Emma Bardac (1862–1934). She demonstrated how her husband had performed the works by singing phrases back to Paul.[7][8]

Later, Doguereau took ten lessons with Ignaz Paderewski in New York.

Professional life

Paul met Maurice Ravel in 1928 in New York during Ravel’s American tour.[9] Paul had been working at the time for Duo-Art, a recording technology developed by the Aeolian Company. Duo-Art had invited Ravel to New York to record piano rolls (“Vallée des cloches” is the only one with sure dates from those sessions). According to David Korevaar, Paul subsequently accompanied Ravel on part of the tour that followed, spending long hours together on the train discussing Ravel’s piano music.[10]

According to Slater:

Part of Paul’s job (in general, not just with Ravel) was determining which notes on the rolls were wrong, and indicating it to the technicians. When making the Duo-Art rolls, certain passages scared Ravel, such as something as simple as an octave passage in two hands, where he asked Paul to play the lower notes of the octave along with him. When the time came, however, he was able to do it himself, and didn't avail himself of Paul's help.

Ravel also told Paul that, "when he wrote Gaspard de la Nuit, he was able to play it all." That included “Scarbo.” Paul was skeptical that Ravel could play “Scarbo,” and repeated his skepticism for years.[11]

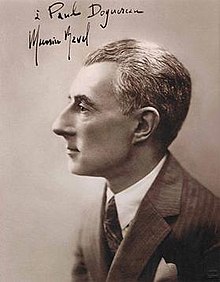

They remained friends, and Paul spoke to Korevaar of visiting Ravel at his home in Montfort, France in later years. There is a photo of Ravel inscribed to Paul in the living room of his Boston home.[12]

Performance

Paul performed in Europe in the 1920s and 1930s. He organized concerts, including one by Stravinsky, in Rome in 1935.[13] Also in the 1930s, supported by a number of Boston patronesses, he studied in Europe with Emil von Sauer and Egon Petri. According to Slater, “Petri was the greatest influence on Paul’s technique and teaching.”[14]

Paul lived in Boston for over sixty years. He met Fanny Peabody Mason in 1937 and it proved to be a meeting that would have an impact on the Boston music scene for decades to come. After her death, Doguereau continued her musical tradition by using the trust left to him to establish the Peabody-Mason Music Foundation, which presented concert performances in Boston for 35 years. On a few occasions Doguereau himself accompanied other artists in their performance. Paul’s performance legacy lives on in his students, including Earl Wild, Peter Orth, David Korevaar, Sergey Schepkin, Andrew Rangell, Harrison Slater, Robert Swan, Stephen Porter and Robert Taub.

Recordings

Paul Doguereau left little in the way of recorded performances. Given that he stopped performing in public in the 1950s, this is hardly surprising. He did however continue to perform privately, and in the last year of his life played the last two Chopin Ballades for friends twice at his home in Mt. Holly, New Jersey.[15]

The earliest recording found by David Korevaar was a piano roll of the Danse Russe from Petrouchka on Ampico.[16] In 1948, the small Boston label Technichord released an album of Fauré songs featuring Paul with two sopranos, Isabel French and Olympia di Napoli.[17] Doguereau also recorded Daniel Pinkham’s Concertino, a work that Pinkham wrote for him in 1950.

In addition, Paul recorded solo repertoire for Technichord that was never released – perhaps the recordings were not up to his exacting standards. Dr. David Korevaar, a former student of Doguereau, was able to study the solo material held by the Library of Congress. The recordings include performances of Ravel’s Sonatine (although missing the second part of the first movement), Fauré’s Third Barcarolle, and Bach’s Chromatic Fantasie.[18]

After hearing the recordings, Korevaar commented:

The performances are all excellent, with brisk tempos and a lack of sentimentality that suits the French repertoire well. The piano sound is surprisingly clean and beautiful; every detail of the performance is audible on the recording. In terms of style, the Ravel is clear, unsentimental, and the last movement is brilliant.[19]

Korevaar found these recorded tempi to be even faster than the indications given by Doguereau when Korevaar studied the work with him, although the high pitch of the transfer may be partly the cause. The recording of Fauré’s Barcarolle has some rubati in the opening. This caught David Korevaar’s attention because he studied the work with Doguereau and remembered his demonstrating in this style.[20]

Boston concerts and competitions

Miss Fanny Peabody Mason, was until her death in 1948, an active patron of music both in the United States and abroad. Her musical interests were piano, singing and chamber music.[21] Miss Mason had met Paul Doguereau early in his career and they became lifelong friends. Mason and Doguereau shared a vision of presenting classical music as a gift to general audiences. Bringing this vision to reality, Miss Mason was benefactress of the Peabody Mason Concerts which Paul directed for 35 years bringing the best talent to Boston audiences, at the best venues, with no admission charge. Rudolph Elie of the Boston Herald hailed the Peabody Mason Concerts, “...of which Paul Doguereau, is at once one of the finest pianists in residence in the city and a musician of great discernment and sensibility, is the guiding spirit.”[22]

Doguereau also organized the early Peabody Mason Piano Competitions, where he served as President and Artistic Director. The piano competition was inspired by Miss Mason’s commitment to, and aspirations for, the arts and serves to showcase and encourage emerging piano talent. The first competition was held in 1981, with others following in 1984 and 1985. The grand prize winner received a yearly stipend plus a New York and a Boston recital. The competition’s rich heritage, its intermittent nature, and its generous prize have lead to a significant reputation and cachet for the award.

Notes

- ^ Associated Press, 5-Mar-2000, Obituary

- ^ New York Times, 9-Mar-2000, Obituary

- ^ The Boston Herald, 3-Mar-2000, Obituary

- ^ Richard Dyer, 10-Mar-2000, The Boston Globe, "Farewell to a Legend"

- ^ David Korevaar, 17-Nov-2007, “A link to the French pianistic tradition: the teaching of Paul Doguereau”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ New York Times, 9-Mar-2000, Obituary

- ^ Op. Cit., Dyer

- ^ Op. Cit., Korevaar

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Harrison Gradwell Slater, “Behind Closed Doors”, Keyboard Classics, 1987

- ^ Op. Cit., Korevaar

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Albert M. Petrak, ed., “Ampico Catalog”, p. 38, Roll No. 6686.

- ^ Musical Quarterly, Quarterly Record List, vol. 34, no. 3 (1948): 459

- ^ Library of Congress, H. Vose Greenough, Jr. Paper Collection, “H. Vose Greenough Collection”

- ^ Op. Cit., Korevaar

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Op. Cit., Slater

- ^ Rudolph Elie, 28-Apr-1950, The Boston Herald, “Chamber Concert”

External links

References

- List of former students of the Conservatoire de Paris

- Korevaar, David (2007). A link to the French pianistic tradition: the teaching of Paul Doguereau. French Music: Performance and Analysis. Laie, Hawaii: Brigham Young University Hawaii.

{{cite conference}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|conferenceurl=|conferenceurl=ignored (|conference-url=suggested) (help) - As of this edit, this article uses content from "Biography", which is licensed in a way that permits reuse under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License, but not under the GFDL. All relevant terms must be followed.

- 1908 births

- 2000 deaths

- Peabody Mason International Piano Competition

- French classical pianists

- American classical pianists

- American recording artists

- French recording artists

- French-American musicians

- People from Suffolk County, Massachusetts

- People from Angers, France

- Alumni of the Conservatoire de Paris

- Duo-Art artists

- Technichord artists