Medieval Warm Period

The Medieval Warm Period (MWP) or Medieval Climate Optimum was a time of warm climate in the North Atlantic region, lasting from about AD 800–1300. It was followed by a cooler period in the North Atlantic termed the Little Ice Age. Some refer to the event as the Medieval Climatic Anomaly as this term emphasizes that effects other than temperature were important.[1] [2]

Initial research

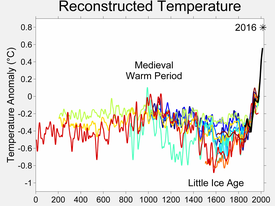

The Medieval Warm Period was a time of warm weather between about AD 800–1300, during the European Medieval period. Initial research on the MWP and the following Little Ice Age (LIA) was largely done in Europe, where the phenomenon was most obvious and clearly documented. It was initially believed that the temperature changes were global.[3] However, this view has been questioned; the IPCC Third Assessment Report from 2001 summarises this research, saying "…current evidence does not support globally synchronous periods of anomalous cold or warmth over this time frame, and the conventional terms of 'Little Ice Age' and 'Medieval Warm Period' appear to have limited utility in describing trends in hemispheric or global mean temperature changes in past centuries".[4] Global temperature records taken from ice cores, tree rings, and lake deposits, have shown that, taken globally, the Earth may have been slightly cooler (by 0.03 degrees Celsius) during the 'Medieval Warm Period' than in the early- and mid-20th century.[5] Crowley and Lowery (2000) [6] note that "there is insufficient documentation as to its existence in the Southern hemisphere."

Palaeoclimatologists developing region-specific climate reconstructions of past centuries conventionally label their coldest interval as "LIA" and their warmest interval as the "MWP".[5][7] Others follow the convention and when a significant climate event is found in the "LIA" or "MWP" time frames, associate their events to the period. Some "MWP" events are thus wet events or cold events rather than strictly warm events, particularly in central Antarctica where climate patterns opposite to the North Atlantic area have been noticed.

By world region

Globally

Studies by Michael Mann et al. find that the MWP shows "warmth that matches or exceeds that of the past decade in some regions, but which falls well below recent levels globally".[8] Their reconstruction of MWP pattern is characterised by warmth over large part of North Atlantic, Southern Greenland, the Eurasian Arctic, and parts of North America which appears to substantially exceed that of modern late 20th century (1961-1990) baseline and is comparable or exceeds that of the past one-to-two decades of in some regions. Certain regions such as central Eurasia, northwestern North America, and (with less confidence) parts of South Atlantic, exhibit anomalous coolness.

North Atlantic

A radiocarbon-dated box core in the Sargasso Sea shows that the sea surface temperature was approximately 1 °C (1.8 °F) cooler than today approximately 400 years ago (the Little Ice Age) and 1700 years ago, and approximately 1 °C warmer than today 1000 years ago (the Medieval Warm Period).[9]

North America

The Vikings took advantage of ice-free seas to colonize Greenland and other outlying lands of the far north.[10] Around 1000AD the climate was sufficiently warm for the north of Newfoundland to support a Viking colony and lead to the descriptor "Vinland". The MWP was followed by the Little Ice Age, a period of cooling that lasted until the 19th century, and the Viking settlements eventually died out. In the Chesapeake Bay, researchers found large temperature excursions during the Medieval Warm Period (about 800–1300) and the Little Ice Age (about 1400–1850), possibly related to changes in the strength of North Atlantic thermohaline circulation.[11] Sediments in Piermont Marsh of the lower Hudson Valley show a dry Medieval Warm period from AD 800–1300.[12]

Prolonged droughts affected many parts of the western United States and especially eastern California and the western Great Basin.[5][13] Alaska experienced three time intervals of comparable warmth: A.D. 1–300, 850–1200, and post-1800.[14] Knowledge of the North American Medieval Warm Period has been useful in dating occupancy periods of certain Native American habitation sites, especially in arid parts of the western U.S.[15] Review of more recent archaeological research shows that as the search for signs of unusual cultural changes during the MCA has broadened, some of these early patterns (e.g. violence and health problems) have been found to be more complicated and regionally varied than previously thought while others (e.g., settlement disruption, deterioration of long distance trade, and population movements) have been further corroborated.[16]

Other regions

The climate in equatorial east Africa has alternated between drier than today, and relatively wet. The drier climate took place during the Medieval Warm Period (~AD 1000–1270).[17]

An ice core from the eastern Bransfield Basin, Antarctic Peninsula, identifies events of the Little Ice Age and Medieval Warm Period.[18] The core shows a distinctly cold period about AD 1000–1100, illustrating that "MWP" is a moveable term, and that during the "warm" period there were, regionally, periods of both warmth and cold.

Corals in the tropical Pacific Ocean suggest that relatively cool, dry conditions may have persisted early in the millennium, consistent with a La Niña-like configuration of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation patterns.[19] Although there is an extreme scarcity of data from Australia (for both the Medieval Warm Period and Little Ice Age) evidence from wave-built shingle terraces for a permanently full Lake Eyre[20] during the ninth and tenth centuries is consistent with this La Niña-like configuration, though of itself inadequate to show how lake levels varied from year to year or what climatic conditions elsewhere in Australia were like.

Adhikari and Kumon (2001), whilst investigating sediments in Lake Nakatsuna in central Japan, verified the existence there of both the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age.[21]

"Temperatures derived from an 18O/16O profile through a stalagmite found in a New Zealand cave (40.67°S, 172.43°E) suggested the Medieval Warm Period to have occurred between AD 1050 and 1400 and to have been 0.75°C warmer than the Current Warm Period."[22] The MWP has also been evidenced in New Zealand by an 1100-year tree-ring record.[23]

See also

- Holocene climatic optimum

- Little Ice Age

- MWP and LIA in IPCC reports

- Historical climatology

- Paleoclimatology

- Temperature record

References

- ^ Bradley, Raymond S. Climate System Research Center. "Climate of the Last Millennium." 2003. February 23, 2007. [1]

- ^ E.L. Ladurie, Times of Feast, Times of Famine: a History of Climate Since the Year 1000 (0(Barbara Bray, tr.) (New York: Doubleday)1971.

- ^ "Paleoclimatology Global Warming - The Data". NOAA. November 10, 2006. Retrieved 2007-07-11.

- ^ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. "Climate Change 2001: Working Group I: The Scientific Basis 2.3.3 Was there a "Little Ice Age" and a "Medieval Warm Period"?". Retrieved 2006-05-04.

- ^ a b c Raymond S. Bradley, Malcolm K. Hughes, Henry F. Diaz (2003). "Climate in Medieval Time" (PDF). Science. 302 (5644): 404–405. doi:10.1126/science.1090372. PMID 14563996.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (links to pdf file) - ^ How Warm Was the Medieval Warm Period? Thomas J. Crowley and Thomas S. Lowery Ambio, Vol. 29, No. 1 (Feb., 2000), pp. 51-54

- ^ Jones, P. D., and M. E. Mann (2004). "Climate over past millennia". Rev. Geophys. 42 (RG2002): 404–405. doi:10.1029/2003RG000143.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mann, Micheal E. (2009). "Global Signatures and Dynamical Origins of the Little Ice Age and Medieval Climate Anomaly" (PDF). Science. 326 (5957): 1256–1260. doi:10.1126/science.1177303. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Keigwin, Lloyd D. (1996). "The Little Ice Age and Medieval Warm Period in the Sargasso Sea". Science. 274 (5292): 1503–1508. doi:10.1126/science.274.5292.1503.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Diamond, Jared (2005). Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0143036556.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Medieval Warm Period, Little Ice Age and 20th Century Temperature Variability from Chesapeake Bay". USGS. Retrieved 2006-05-04.

- ^ "Marshes Tell Story Of Medieval Drought, Little Ice Age, And European Settlers Near New York City". Earth Observatory News. May 19, 2005. Retrieved 2006-05-04.

- ^ Stine, Scott (1994). "Extreme and persistent drought in California and Patagonia during mediaeval time". Nature. 369 (6481): 546–549. doi:10.1038/369546a0.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Hu FS, Ito E, Brown TA, Curry BB, Engstrom DR (2001). "Pronounced climatic variations in Alaska during the last two millennia". PNAS. 98 (19): 10552–10556. doi:10.1073/pnas.181333798. PMID 11517320.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ C. Michael Hogan (2008) Los Osos Back Bay, Megalithic Portal, editor A. Burnham.

- ^ Jones, Terry L. (2008). "Archaeological perspectives on the effects of medieval drought in prehistoric California". Quaternary International. 188 (1): 41–58. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2007.07.007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Drought In West Linked To Warmer Temperatures". Earth Observatory News. 2004-10-07. Retrieved 2006-05-04.

- ^ Khim, B-K (2002). "Unstable Climate Oscillations during the Late Holocene in the Eastern Bransfield Basin, Antarctic Peninsula". Quaternary Research. 58 (3): 234–245(12). doi:10.1006/qres.2002.2371. Retrieved 2006-05-04.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Cobb, Kim M. (July 8, 2003). "The Medieval Cool Period And The Little Warm Age In The Central Tropical Pacific? Fossil Coral Climate Records Of The Last Millennium". The Climate of the Holocene (ICCI) 2003. Retrieved 2006-05-04.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Allen, Robert J.; The Australasian Summer Monsoon, Teleconnections, and Flooding in the Lake Eyre Basin; published 1985 by Royal Geographical Society of Australasia, S.A. Branch; ISBN 0909112096

- ^ Adhikari DP, Kumon, F. (2001). "Climatic changes during the past 1300 years as deduced from the sediments of Lake Nakatsuna, central Japan". Limnology. 2 (3): 157–168. doi:10.1007/s10201-001-8031-7.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wilson, A.T., Hendy, C.H. and Reynolds, C.P. 1979. Short-term climate change and New Zealand temperatures during the last millennium. Nature 279: 315-317.

- ^ Cook E.R., Palmer J.G., D’Arrigo R.D. (2002), "Evidence for a ‘Medieval Warm Period’ in a 1,100 year tree-ring reconstruction of past austral summer temperatures in New Zealand", Geophysical Research Letters, 29, doi:10.1029/2001GL014580.

Further reading

- M.K. Hughes and H.F. Diaz, "Was there a 'Medieval Warm Period?", Climatic Change 26: 109-142, March 1994