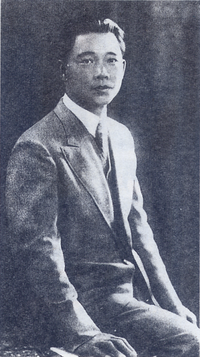

Wang Jingwei

Wang Jingwei (traditional Chinese: 汪精衛; simplified Chinese: 汪精卫; pinyin: Wāng Jīngwèi; Wade-Giles: Wang Ching-wei) (May 4, 1883 – November 10, 1944), alternate name Wang Zhaoming (traditional Chinese: 汪兆銘), was a Chinese politician. He was initially known as a member of the left wing of the Kuomintang (KMT), but he was staunchly anti-Communist, and his politics veered sharply to the right later in his career. A close associate of Sun Yat-sen, Wang is most noted for disagreements with Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and his formation of a Japanese-supported collaborationist government in Nanjing. For this role he has often been labeled as a Hanjian, or "Traitor to the Han Chinese". His name in China is also now a term used to refer to a traitor, similar to the American English "Benedict Arnold" or European "Quisling".

Rise to prominence

Born in Sanshui, Guangdong, but of Zhejiang origin, Wang went to Japan as an international student sponsored by the Qing government in 1903 and joined the Tongmenghui in 1905. As a young man, Wang came to blame the Qing dynasty for holding China back and making it too weak to fight off exploitation by Western Imperialist powers. While in Japan, Wang became a close confidant of Sun Yat-Sen, and would later go on to become one of the most important members of the early Kuomintang.[1]

In the years leading up to the 1911 Revolution, Wang was active in opposing the Qing. Wang gained prominence during this period as an excellent public speaker and a staunch advocate of Chinese nationalism. He was jailed for plotting an assassination of the regent, the 2nd Prince Chun, and readily admitted his guilt at trial. He remained in jail from 1910 until the Wuchang Uprising the next year, and became something of a national hero upon his release.[2]

During and after the 1911 Revolution, Wang’s political life was defined by his opposition to Western Imperialism.

In the early 1920s, Wang held several posts in Sun Yat-sen's Revolutionary Government in Guangzhou, but following Sun's death in 1925 he faced a powerful challenge for leadership of the KMT. Following the Zhongshan Warship Incident, he lost control of the party and army to Chiang Kai-shek.

Rivalry with Chiang Kai-shek

- See also April 12 Incident

During the Northern Expedition, Wang was the leading figure in the left-leaning faction of the KMT that called for continued cooperation with the Communist Party of China. It should be noted however, that Wang was personally opposed to Communism and regarded the KMT’s Comintern advisors with suspicion.[3] He did not believe that Communists could be true patriots or true Chinese nationalists.[4] Wang's faction, which had set up a new KMT capital at Wuhan in early 1927, was opposed by Chiang Kai-shek, who was in the midst of a bloody purge of Communists in Shanghai and was calling for a push north. The separation between these two sides was known as the Ninghan Separation (simplified Chinese: 宁汉分裂; traditional Chinese: 寧漢分裂; pinyin: Nínghàn Fenlìe). Wang's faction was weak militarily however, and was ousted by a local warlord the same year. Lacking the military or financial resources to resist the increasingly powerful Chiang, his faction was forced to rejoin Chiang Kai-shek at Nanjing in September 1927.

In 1930, Wang tried another abortive coup against Chiang, this time with the aid of Feng Yuxiang and Yan Xishan in the Central Plains War. In 1932, Wang attempted to form a rival KMT government in Beijing. As a result of these power struggles within the KMT, Wang was forced to spend much of his time in exile. He traveled to Germany, and maintained some contact with Adolf Hitler. The effectiveness of the KMT was constantly hindered by leadership and personal struggles, such as that between Wang and Chiang.

Wang reconciled with Chiang's Nanjing government in the early 1930s and held prominent posts for most of the decade, and accompanied the government on its retreat to Chongqing during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945). During this time, he organized some right-wing groups under European fascist lines inside the KMT. Wang was originally part of the pro-war group, but after initial Chinese defeats Wang became known for his pessimistic view on China's chances in a war against Japan. He often voiced defeatist opinions in KMT staff meetings, and continued to express his view that Western Imperialism was the greater danger to China, much to the chagrin of his associates. Wang believed that China needed to reach a negotiated settlement with Japan so that Asia could resist Western Powers.

Japanese collaboration

In late 1938, Wang left Chongqing for Hanoi, French Indochina, where he stayed for three months. During this time, he was wounded in an assassination attempt by KMT agents. Wang then flew to Shanghai, where he entered negotiations with Japanese authorities. The Japanese invasion had given him the opportunity he had long sought to establish a new government outside of Chiang Kai-shek’s control.

On March 30, 1940, he became the head of state of what came to be known as the Wang Jingwei Government based in Nanjing, serving as the President of the Executive Yuan and Chairman of the National Government (行政院長兼國民政府主席). The Government of National Salvation, which Wang headed, was established on the Three Principles of Pan-Asianism, anti-Communism, and Opposition to Chiang Kai-shek. Wang continued to maintain his contacts with German and Italian fascists he had established while in exile. Wang lived in Japan during wartime, along with official Japanese advisers. He died in Nagoya on November 10, 1944, less than a year before Japan's surrender to the Allies, thus avoiding a trial for treason. Many of his senior followers who lived to see the end of the war were executed. Wang was buried in Nanjing near the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum, in an elaborately-constructed tomb. Soon after Japan's defeat, the Kuomintang government under Chiang Kai-shek moved its capital back to Nanjing, destroyed Wang's tomb, and burned the body. Today the site is commemorated with a small pavilion that notes Wang as a traitor.

Assassination

While most accounts attribute Wang's death to an illness brought on by a wound received in a 1935 assassination attempt[5], it has been asserted that Wang was in fact assassinated by two Chinese men while being chauffeur driven to his Shanghai mansion on Yu Yuen Road. This assassination was subsequently covered up by the Japanese.[6]

Life under the Wang Jingwei Regime

Since Wang’s government only held authority over territories under Japanese military occupation, there was a limited amount that officials loyal to Wang could do to ease the suffering of Chinese under Japanese occupation. Wang himself became a focal point of anti-Japanese resistance, and was demonized and branded as an “arch-traitor” in both KMT and Communist propaganda. Wang and his government were deeply unpopular with the Chinese populace, who regarded them as traitors to both the Chinese state and Han Chinese identity.[7] Furthermore, Wang’s rule was constantly undermined by resistance and sabotage.

Post-War assessment and legacy

For his role in the Pacific War, Wang has been considered a traitor by most post-World War II Chinese historians in both Taiwan and Mainland China. The Mainland’s Communist government despised Wang not only for his collaboration but also for his anti-Communism, while the KMT downplayed his anti-Communism and emphasized his collaboration and betrayal of Chiang Kai-Shek. The Communists also used his KMT ties to demonstrate what they saw as the duplicitous, treasonous nature of the Kuomintang. Both sides downplayed his association with Sun Yat-Sen because of his eventual collaboration.[8]

However, some took a different view and regard his collaboration with the Japanese as a good faith attempt to salvage China from foreign imperialism. That reasoning was rejected by both the Kuomintang and the Communists. The Kuomintang government tried other major collaborators for treason after the war. The Communist government further retaliated, executing many lower-level officials from Wang's government.

Notes

- ^ The Biographical Dictionary of Republican China. Eds. Howard L. Boorman and Richard C. Howard,(New York: Columbia University Press, 1970), 369.

- ^ Ibid, 370-371.

- ^ Dongyoun Hwang. Wang Jingwei, The National Government, and the Problem of Collaboration. Ph.D. Dissertation, Duke University. UMI Dissertation Services, Ann Arbor Michigain. 2000, 118.

- ^ Ibid, 148.

- ^ Wang Ke-Wen, "Modern China: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture and Nationalism" Taylor & Francis (1998), 380

- ^ Ellis Jacob, "The Shanghai I Knew: A Foreign Native in Pre-Revolutionary China" ComteQ Publishing (2007), 77

- ^ Frederic Wakeman, Jr. “Hanjian (Traitor) Collaboration and Retribution in Wartime Shanghai.” In Wen-hsin Yeh, ed. Becoming Chinese: Passages to Modernity and Beyond. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 322.

- ^ Wang Ke-Wan, “Irreversible Verdict? Historical Assessments of Wang Jingwei in the People’s Republic and Taiwan.” Twentieth Century China. Vol. 28, No. 1. (November 2003), 59.

Further reading

- David P. Barrett and Larry N. Shyu, eds.; Chinese Collaboration with Japan, 1932–1945: The Limits of Accommodation Stanford University Press 2001.

- Gerald Bunker, The Peace Conspiracy; Wang Ching-wei and the China war, 1937-1941 Harvard University Press, 1972.

- James C. Hsiung and Steven I. Levine, eds. China's Bitter Victory: The War with Japan, 1937–1945 M. E. Sharpe, 1992.

- Ch'i Hsi-sheng, Nationalist China at War: Military Defeats and Political Collapse, 1937–1945 University of Michigan Press, 1982.

See also

- Wang Jingwei Government

- Second Sino-Japanese War

- Kuomintang

- History of the Republic of China

- Vichy France

External links

- Japan's Asian Axis Allies — Chinese National Government of Nanking