Fahrenheit 451

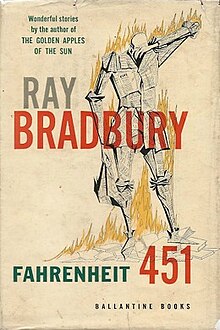

First edition cover (clothbound) | |

| Author | Ray Bradbury |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Joseph Mugnaini[1] |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Dystopian[2] |

| Published | October 19, 1953 (Ballantine Books)[3] |

| Publication place | United States |

| Pages | 156 |

| ISBN | 978-0-7432-4722-1 (current cover edition) |

| OCLC | 53101079 |

| 813.54 22 | |

| LC Class | PS3503.R167 F3 2003 |

Fahrenheit 451 is a 1953 dystopian novel by American writer Ray Bradbury.[4] It presents a future American society where books have been outlawed and "firemen" burn any that are found.[5] The novel follows in the viewpoint of Guy Montag, a fireman who soon becomes disillusioned with his role of censoring literature and destroying knowledge, eventually quitting his job and committing himself to the preservation of literary and cultural writings.

Fahrenheit 451 was written by Bradbury during the Second Red Scare and the McCarthy era, inspired by the book burnings in Nazi Germany and by ideological repression in the Soviet Union.[6] Bradbury's claimed motivation for writing the novel has changed multiple times. In a 1956 radio interview, Bradbury said that he wrote the book because of his concerns about the threat of burning books in the United States.[7] In later years, he described the book as a commentary on how mass media reduces interest in reading literature.[8] In a 1994 interview, Bradbury cited political correctness as an allegory for the censorship in the book, calling it "the real enemy these days" and labeling it as "thought control and freedom of speech control".[9]

The writing and theme within Fahrenheit 451 was explored by Bradbury in some of his previous short stories. Between 1947 and 1948, Bradbury wrote "Bright Phoenix", a short story about a librarian who confronts a "Chief Censor", who burns books. An encounter Bradbury had in 1949 with the police inspired him to write the short story "The Pedestrian" in 1951. In "The Pedestrian", a man going for a nighttime walk in his neighborhood is harassed and detained by the police. In the society of "The Pedestrian", citizens are expected to watch television as a leisurely activity, a detail that would be included in Fahrenheit 451. Elements of both "Bright Phoenix" and "The Pedestrian" would be combined into The Fireman, a novella published in Galaxy Science Fiction in 1951. Bradbury was urged by Stanley Kauffmann, an editor at Ballantine Books, to make The Fireman into a full novel. Bradbury finished the manuscript for Fahrenheit 451 in 1953, and the novel was published later that year.

Upon its release, Fahrenheit 451 was a critical success, albeit with notable dissenters; the novel's subject matter led to its censorship in apartheid South Africa and various schools in the United States. In 1954, Fahrenheit 451 won the American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Literature and the Commonwealth Club of California Gold Medal.[10][11][12] It later won the Prometheus "Hall of Fame" Award in 1984[13] and a "Retro" Hugo Award in 2004.[14] Bradbury was honored with a Spoken Word Grammy nomination for his 1976 audiobook version.[15] The novel has also been adapted into films, stage plays, and video games. Film adaptations of the novel include a 1966 film directed by François Truffaut starring Oskar Werner as Guy Montag and a 2018 television film directed by Ramin Bahrani starring Michael B. Jordan as Montag, both of which received a mixed critical reception. Bradbury himself published a stage play version in 1979 and helped develop a 1984 interactive fiction video game of the same name, as well as a collection of his short stories titled A Pleasure to Burn.[16] Two BBC Radio dramatizations were also produced.

Historical and biographical context

[edit]

The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), formed in 1938 to investigate American citizens and organizations suspected of having communist ties, held hearings in 1947 to investigate alleged communist influence in Hollywood movie-making.[17] The government's interference in the affairs of artists and creative types infuriated Bradbury;[18] he was concerned about the workings of his government, and a late 1949 nighttime encounter with an overzealous police officer would inspire Bradbury to write "The Pedestrian", a short story which would go on to become "The Fireman" and then Fahrenheit 451. The rise of Senator Joseph McCarthy's McCarthyism persecution of accused communists, beginning in 1950, deepened Bradbury's contempt for government overreach.[19][20]

The Golden Age of Radio occurred between the early 1920s to the late 1950s, during Bradbury's early life, while the transition to the Golden Age of Television began right around the time he started to work on the stories that would eventually lead to Fahrenheit 451. Bradbury saw these forms of media as a threat to the reading of books, indeed as a threat to society, as he believed they could act as a distraction from important affairs. This contempt for mass media and technology would express itself through Mildred and her friends and is an important theme in the book.[21]

Bradbury's lifelong passion for books began at an early age. After he graduated from high school, his family could not afford for him to attend college, so Bradbury began spending time at the Los Angeles Public Library where he educated himself.[22] As a frequent visitor to his local libraries in the 1920s and 1930s, he recalls being disappointed because they did not stock popular science fiction novels, like those of H. G. Wells, because, at the time, they were not deemed literary enough. Between this and learning about the destruction of the Library of Alexandria,[23] a great impression was made on Bradbury about the vulnerability of books to censure and destruction.

Later, as a teenager, Bradbury was horrified by the Nazi book burnings stating, "When I was fifteen years old, Hitler burned books in the streets of Berlin. And it terrified me".[24] Bradbury was also influenced by Joseph Stalin's campaign of political repression, the Great Purge, in which writers and poets, among many others, were arrested and often executed, stating, "They burned the authors instead of the books."[6]

Plot summary

[edit]"The Hearth and the Salamander"

[edit]In a distant future,[note 1][25] Guy Montag is a fireman employed to burn outlawed books, along with the houses they are hidden in. One fall night while returning from work, he meets his new neighbor Clarisse McClellan, a teenage girl whose free-thinking ideals and liberating spirit cause him to question his life and perceived happiness. Montag returns home to find that his wife Mildred has overdosed on sleeping pills, and he calls for medical attention. Two EMTs later pump her stomach and change her blood. After they leave to rescue another overdose victim, Montag overhears Clarisse and her family talking about their illiterate society. Shortly afterward, Montag's mind is bombarded with Clarisse's subversive thoughts and the memory of Mildred's near-death. Over the next few days, Clarisse meets Montag each night as he walks home. Clarisse's simple pleasures and interests make her an outcast among her peers, and she is forced to go to therapy for her behavior. Montag always looks forward to the meetings, but one day, Clarisse goes missing.[26]

In the following days, while he and other firemen are ransacking the book-filled house of an old woman and drenching it in kerosene, Montag steals a book. The woman refuses to leave her house and her books, choosing instead to light a match and burn herself alive. Jarred by the suicide, Montag returns home and hides the book under his pillow. Later, Montag asks Mildred if she has heard anything about Clarisse. She reveals that Clarisse's family moved away after Clarisse was hit by a speeding car and died four days ago. Dismayed by her failure to mention this earlier, Montag uneasily tries to fall asleep. Outside he suspects the presence of "The Mechanical Hound", an eight-legged[27] robotic dog-like creature that resides in the firehouse and aids the firemen in hunting book hoarders.

Montag awakens ill the next morning. Mildred tries to care for her husband but finds herself more involved in the "parlor wall" entertainment in the living room – large televisions filling the walls. Montag suggests he should take a break from being a fireman, and Mildred panics over the thought of losing the house and her parlor wall "family". Captain Beatty, Montag's fire chief, visits Montag to see how he is doing. Sensing his concerns, Beatty recounts the history of how books had lost their value and how the firemen were adapted for their current role: over decades, people began to embrace new media (like film and television), sports, and an ever-quickening pace of life. Books were abridged or degraded to accommodate shorter attention spans. At the same time, advances in technology resulted in nearly all buildings being made with fireproof materials, and firemen preventing fires were no longer necessary. The government then instead turned the firemen into officers of society's peace of mind: instead of putting out fires, they were charged with starting them, specifically to burn books, which were condemned as sources of confusing and depressing thoughts that complicated people's lives. After an awkward exchange between Mildred and Montag over the book hidden under his pillow, Beatty becomes suspicious and casually adds a passing threat before leaving; he says that if a fireman had a book, he would be asked to burn it within the following twenty-four hours. If he refused, the other firemen would come and burn it for him. The encounter leaves Montag utterly shaken.

Montag later reveals to Mildred that, over the last year, he has accumulated books that are hidden in their ceiling. In a panic, Mildred grabs a book and rushes to throw it in the kitchen incinerator, but Montag subdues her and says they are going to read the books to see if they have value. If they do not, he promises the books will be burned and their lives will return to normal.

"The Sieve and the Sand"

[edit]Mildred refuses to go along with Montag's plan, questioning why she or anyone else should care about books. Montag goes on a rant about Mildred's suicide attempt, Clarisse's disappearance and death, the woman who burned herself, and the imminent war that goes ignored by the masses. He suggests that perhaps the books of the past have messages that can save society from its own destruction. Even still, Mildred remains unconvinced.

Conceding that Mildred is a lost cause, Montag will need help to understand the books. He remembers an old man named Faber, an English professor before books were banned, whom he once met in a park. Montag visits Faber's home carrying a copy of the Bible, the book he stole at the woman's house. Once there, after multiple attempts to ask, Montag forces the scared and reluctant Faber into helping him by methodically ripping pages from the Bible. Faber concedes and gives Montag a homemade earpiece communicator so that he can offer constant guidance.

At home, Mildred's friends, Mrs. Bowles and Mrs. Phelps, arrive to watch the "parlor walls". Not interested in this entertainment, Montag turns off the walls and tries to engage the women in meaningful conversation, only for them to reveal just how indifferent, ignorant, and callous they truly are. Enraged, Montag shows them a book of poetry. This confuses the women and alarms Faber, who is listening remotely. Mildred tries to dismiss Montag's actions as a tradition firemen act out once a year: they find an old book and read it as a way to make fun of how silly the past is. Montag proceeds to recite a poem,[note 2] causing Mrs. Phelps to cry. Soon, the two women leave.

Montag hides his books in the backyard before returning to the firehouse late at night. There, Montag hands Beatty a book to cover for the one he believes Beatty knows he stole the night before, which is tossed into the trash. Beatty reveals that, despite his disillusionment, he was once an enthusiastic reader. A fire alarm sounds and Beatty picks up the address from the dispatcher system. They drive in the fire truck to the unexpected destination: Montag's house.

"Burning Bright"

[edit]Beatty orders Montag to destroy his house with a flamethrower, rather than the more powerful "salamander" that is usually used by the fire team, and tells him that his wife and her friends reported him. Montag watches as Mildred walks out of the house, too traumatized about losing her parlor wall 'family' to even acknowledge her husband's existence or the situation going on around her, and catches a taxi. Montag complies, destroying the home piece by piece, but Beatty discovers his earpiece and plans to hunt down Faber. Montag threatens Beatty with the flamethrower and, after Beatty taunts him, Montag burns Beatty alive. As Montag tries to escape the scene, the Mechanical Hound attacks him, managing to inject his leg with an anesthetic. He destroys the Hound with the flamethrower and limps away. While escaping, Montag concludes that Beatty wanted to die a long time ago, having goaded him and provided him with a weapon.

Montag runs towards Faber's house. En route, he crosses a road as a car attempts to run him over, but he manages to evade the vehicle, almost suffering the same fate as Clarisse and losing his knee. Faber urges him to make his way to the countryside and contact a group of exiled book-lovers who live there. Faber plans to leave on a bus heading to St. Louis, Missouri, where he and Montag can rendezvous later. Meanwhile, another Mechanical Hound is released to track down and kill Montag, with news helicopters following it to create a public spectacle. After wiping his scent from around the house in hopes of thwarting the Hound, Montag leaves. He escapes the manhunt by wading into a river and floating downstream, where he meets the book-lovers. They predicted Montag's arrival while watching the TV.

The drifters are all former intellectuals. They have each memorized books should the day arrive that society comes to an end, with the survivors learning to embrace the literature of the past. Wanting to contribute to the group, Montag finds that he partially memorized the Book of Ecclesiastes, discovering that the group has a special way of unlocking photographic memory. While discussing about their learnings, Montag and the group watch helplessly as bombers fly overhead and annihilate the city with nuclear weapons: the war has begun and ended in the same night. While Faber would have left on the early bus, everyone else (possibly including Mildred) is killed. Injured and dirtied, Montag and the group manage to survive the shockwave.

When the war is over, the exiles return to the city to rebuild society.

Characters

[edit]- Guy Montag is the protagonist and a fireman who presents the dystopian world in which he lives first through the eyes of a worker loyal to it, then as a man in conflict about it, and eventually as someone resolved to be free of it. Throughout most of the book, Montag lacks knowledge and believes only what he hears. Clarisse McClellan inspires Montag's change, even though they do not know each other for very long.

- Clarisse McClellan is a teenage girl one month short of her 17th birthday[note 3] who is Montag's neighbor.[28] She walks with Montag on his trips home from work. A modern critic has described her as an example of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl,[29] as Clarisse is an unusual sort of person compared to the others inhabiting the bookless, hedonistic society: outgoing, naturally cheerful, unorthodox, and intuitive. She is unpopular among peers and disliked by teachers for asking "why" instead of "how" and focusing on nature rather than on technology. A few days after her first meeting with Montag, she disappears without any explanation; Mildred tells Montag (and Captain Beatty confirms) that Clarisse was hit by a speeding car and that her family moved away following her death. It is implied that Beatty may have assassinated Clarisse. In the afterword of a later edition, Bradbury notes that the 1966 film adaptation changed the ending so that Clarisse (who, in the film, is now a 20-year-old schoolteacher who was fired for being unorthodox) was living with the exiles. Bradbury, far from being displeased by this, was so happy with the new ending that he wrote it into his later stage edition.

- Mildred "Millie" Montag is Guy Montag's wife. She is addicted to sleeping pills, absorbed in the shallow dramas played on her "parlor walls" (large, flat-panel televisions), and indifferent to the oppressive society around her. She is described in the book as "thin as a praying mantis from dieting, her hair burnt by chemicals to a brittle straw, and her flesh like white bacon." Despite her husband's attempts to break her from the spell society has on her, Mildred continues to be shallow and indifferent. After Montag scares her friends away by reading Dover Beach, and finding herself unable to live with someone who has been hoarding books, Mildred betrays Montag by reporting him to the firemen and abandoning him, and presumably dies when the city is bombed.

- Captain Beatty is Montag's boss and the book's main antagonist. Once an avid reader, he has come to hate books due to their unpleasant content and contradicting facts and opinions. After he forces Montag to burn his own house, Montag kills him with a flamethrower. In a scene written years later by Bradbury for the Fahrenheit 451 play, Beatty invites Montag to his house where he shows him walls of books left to molder on their shelves.

- Stoneman and Black are Montag's coworkers at the firehouse. They do not have a large impact on the story and function only to show the reader the contrast between the firemen who obediently do as they are told and someone like Montag, who formerly took pride in his job but subsequently realizes how damaging it is to society. Black is later framed by Montag for possessing books.

- Faber is a former English professor. He has spent years regretting that he did not defend books when he saw the moves to ban them. Montag turns to him for guidance, remembering him from a chance meeting in a park sometime earlier. Faber at first refuses to help Montag and later realizes Montag is only trying to learn about books, not destroy them. He secretly communicates with Montag through an electronic earpiece and helps Montag escape the city, then gets on a bus to St. Louis and escapes the city himself before it is bombed. Bradbury notes in his afterword that Faber is part of the name of a German manufacturer of pencils, Faber-Castell but it is also the name of a famous publishing company, Faber and Faber.

- Mrs. Ann Bowles and Mrs. Clara Phelps are Mildred's friends and representative of the anti-intellectual, hedonistic mainstream society presented in the novel. During a social visit to Montag's house, they brag about ignoring the bad things in their lives and have a cavalier attitude towards the upcoming war, their husbands, their children, and politics. Mrs. Phelps' husband Pete was called in to fight in the upcoming war (and believes that he'll be back in a week because of how quick the war will be) and thinks having children serves no purpose other than to ruin lives. Mrs. Bowles is a three-times-married single mother. Her first husband divorced her, her second died in a jet accident, and her third committed suicide by shooting himself in the head. She has two children who do not like or respect her due to her permissive, often negligent and abusive parenting; Mrs. Bowles brags that her kids beat her up, and she's glad she can hit back. When Montag reads Dover Beach to them, he strikes a chord in Mrs. Phelps, who starts crying over how hollow her life is. Mrs. Bowles chastises Montag for reading "silly awful hurting words".

- Granger is the leader of a group of wandering intellectual exiles who memorize books in order to preserve their contents.

Title

[edit]The title page of the book explains the title as follows: Fahrenheit 451—The temperature at which book paper catches fire and burns.... On inquiring about the temperature at which paper would catch fire, Bradbury had been told that 451 °F (233 °C) was the autoignition temperature of paper.[30][31] In various studies, scientists have placed the autoignition temperature at a range of temperatures between 424 and 475 °F (218 and 246 °C), depending on the type of paper.[32][33]

Writing and development

[edit]Fahrenheit 451 developed out of a series of ideas Bradbury had visited in previously written stories. For many years, he tended to single out "The Pedestrian" in interviews and lectures as sort of a proto-Fahrenheit 451. In the Preface of his 2006 anthology Match to Flame: The Fictional Paths to Fahrenheit 451 he states that this is an oversimplification.[34] The full genealogy of Fahrenheit 451 given in Match to Flame is involved. The following covers the most salient aspects.[35]

Between 1947 and 1948,[36] Bradbury wrote the short story "Bright Phoenix" (not published until the May 1963 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction[37][38]) about a librarian who confronts a book-burning "Chief Censor" named Jonathan Barnes.

In late 1949,[39] Bradbury was stopped and questioned by a police officer while walking late one night.[40][41] When asked "What are you doing?", Bradbury wisecracked, "Putting one foot in front of another."[40][41] This incident inspired Bradbury to write the 1951 short story "The Pedestrian".[note 4][40][41]

In "The Pedestrian", Leonard Mead is harassed and detained by the city's only remotely operated police cruiser for taking nighttime walks, something that has become extremely rare in this future-based setting, as everybody else stays inside and watches television ("viewing screens"). Alone and without an alibi, Mead is taken to the "Psychiatric Center for Research on Regressive Tendencies" for his peculiar habit. Fahrenheit 451 would later echo this theme of an authoritarian society distracted by broadcast media.[citation needed]

Bradbury expanded the book-burning premise of "Bright Phoenix"[42] and the totalitarian future of "The Pedestrian"[43] into "The Fireman", a novella published in the February 1951 issue of Galaxy Science Fiction.[44][45] "The Fireman" was written in the basement of UCLA's Powell Library on a typewriter that he rented for a fee of ten cents per half hour.[46] The first draft was 25,000 words long and was completed in nine days.[47]

Urged by a publisher at Ballantine Books to double the length of his story to make a novel, Bradbury returned to the same typing room and made the story 25,000 words longer, again taking just nine days.[46] The title "Fahrenheit 451" came to him on January 22. The final manuscript was ready in mid-August, 1953.[48] The resulting novel, which some considered as a fix-up[49] (despite being an expanded rewrite of one single novella), was published by Ballantine in 1953.[50]

Supplementary material

[edit]Bradbury has supplemented the novel with various front and back matter, including a 1979 coda,[51] a 1982 afterword,[52] a 1993 foreword, and several introductions.

Publication history

[edit]The first U.S. printing was a paperback version from October 1953 by The Ballantine Publishing Group. Shortly after the paperback, a hardback version was released that included a special edition of 200 signed and numbered copies bound in asbestos.[53][54][55] These were technically collections because the novel was published with two short stories, "The Playground" and "And the Rock Cried Out", which have been omitted from later printings.[1][56] A few months later, the novel was serialized in the March, April, and May 1954 issues of nascent Playboy magazine.[10][57]

Expurgation

[edit]Starting in January 1967, Fahrenheit 451 was subject to expurgation by its publisher, Ballantine Books, with the release of the "Bal-Hi Edition" aimed at high school students.[58][59] Among the changes made by the publisher were the censorship of the words "hell", "damn", and "abortion"; the modification of seventy-five passages; and the changing of two incidents.[59][60]

In the first incident, a drunk man is changed to a "sick man", while the second involves cleaning fluff out of a human navel, which instead becomes "cleaning ears" in the other.[59][61] For a while, both the censored and uncensored versions were available concurrently, but by 1973, Ballantine was publishing only the censored version.[61][62] That continued until 1979, when it came to Bradbury's attention:[61][62]

In 1979, one of Bradbury's friends showed him an expurgated copy of the book. Bradbury demanded that Ballantine Books withdraw that version and replace it with the original, and in 1980 the original version once again became available. In this reinstated work, in the Author's Afterword, Bradbury relates to the reader that it is not uncommon for a publisher to expurgate an author's work, but he asserts that he himself will not tolerate the practice of manuscript "mutilation".

The "Bal-Hi" editions are now referred to by the publisher as the "Revised Bal-Hi" editions.[63]

Non-print publications

[edit]An audiobook version read by Bradbury himself was released in 1976 and received a Spoken Word Grammy nomination.[15] Another audiobook was released in 2005 narrated by Christopher Hurt.[64] The e-book version was released in December 2011.[65][66]

Reception

[edit]In 1954, Galaxy Science Fiction reviewer Groff Conklin placed the novel "among the great works of the imagination written in English in the last decade or more."[67] The Chicago Sunday Tribune's August Derleth described the book as "a savage and shockingly prophetic view of one possible future way of life", calling it "compelling" and praising Bradbury for his "brilliant imagination".[68] Over half a century later, Sam Weller wrote, "upon its publication, Fahrenheit 451 was hailed as a visionary work of social commentary."[69] Today, Fahrenheit 451 is still viewed as an important cautionary tale about conformity and the evils of government censorship.[70]

When the novel was first published, there were those who did not find merit in the tale. Anthony Boucher and J. Francis McComas were less enthusiastic, faulting the book for being "simply padded, occasionally with startlingly ingenious gimmickry, ... often with coruscating cascades of verbal brilliance [but] too often merely with words."[71] Reviewing the book for Astounding Science Fiction, P. Schuyler Miller characterized the title piece as "one of Bradbury's bitter, almost hysterical diatribes," while praising its "emotional drive and compelling, nagging detail."[72] Similarly, The New York Times was unimpressed with the novel and further accused Bradbury of developing a "virulent hatred for many aspects of present-day culture, namely, such monstrosities as radio, TV, most movies, amateur and professional sports, automobiles, and other similar aberrations which he feels debase the bright simplicity of the thinking man's existence."[73]

Fahrenheit 451 was number seven on the list of "Top Check Outs OF ALL TIME" by the New York Public Library[74]

Censorship/banning incidents

[edit]In the years since its publication, Fahrenheit 451 has occasionally been banned, censored, or redacted in some schools at the behest of parents or teaching staff either unaware of or indifferent to the inherent irony in such censorship. Notable incidents include:

- In Apartheid South Africa, the book was burned along with thousands of banned publications between the 1950s and 1970s.[75]

- In 1987, Fahrenheit 451 was given "third tier" status by the Bay County School Board in Panama City, Florida, under superintendent Leonard Hall's new three-tier classification system. Third tier was meant for books to be removed from the classroom for "a lot of vulgarity". After a resident class-action lawsuit, a media stir, and student protests, the school board abandoned their tier-based censorship system and approved all the currently used books.[76]

- In 1992, Venado Middle School in Irvine, California, gave copies of Fahrenheit 451 to students with all "obscene" words blacked out.[77] Parents contacted the local media and succeeded in reinstalling the uncensored copies.[77]

- In 2006, parents of a 10th-grade high school student in Montgomery County, Texas, demanded the book be banned from their daughter's English class reading list.[78] Their daughter was assigned the book during Banned Books Week, but stopped reading several pages in due to what she considered the offensive language and description of the burning of the Bible. In addition, the parents protested the violence, portrayal of Christians, and depictions of firemen in the novel.[78]

Themes

[edit]Discussions about Fahrenheit 451 often center on its story foremost as a warning against state-based censorship. Indeed, when Bradbury wrote the novel during the McCarthy era, he was concerned about censorship in the United States. During a radio interview in 1956,[79][80] Bradbury said

I wrote this book at a time when I was worried about the way things were going in this country four years ago. Too many people were afraid of their shadows; there was a threat of book burning. Many of the books were being taken off the shelves at that time. And of course, things have changed a lot in four years. Things are going back in a very healthy direction. But at the time I wanted to do some sort of story where I could comment on what would happen to a country if we let ourselves go too far in this direction, where then all thinking stops, and the dragon swallows his tail, and we sort of vanish into a limbo and we destroy ourselves by this sort of action.

As time went by, Bradbury tended to dismiss censorship as a chief motivating factor for writing the story. Instead he usually claimed that the real messages of Fahrenheit 451 were about the dangers of an illiterate society infatuated with mass media and the threat of minority and special interest groups to books. In the late 1950s, Bradbury recounted

In writing the short novel Fahrenheit 451, I thought I was describing a world that might evolve in four or five decades. But only a few weeks ago, in Beverly Hills one night, a husband and wife passed me, walking their dog. I stood staring after them, absolutely stunned. The woman held in one hand a small cigarette-package-sized radio, its antenna quivering. From this sprang tiny copper wires which ended in a dainty cone plugged into her right ear. There she was, oblivious to man and dog, listening to far winds and whispers and soap-opera cries, sleep-walking, helped up and down curbs by a husband who might just as well not have been there. This was not fiction.[81]

This story echoes Mildred's "Seashell ear-thimbles" (i.e., a brand of in-ear headphones) that act as an emotional barrier between her and Montag. In a 2007 interview, Bradbury maintained that people misinterpret his book and that Fahrenheit 451 is really a statement on how mass media like television marginalizes the reading of literature.[8] Regarding minorities, he wrote in his 1979 Coda

'There is more than one way to burn a book. And the world is full of people running about with lit matches. Every minority, be it Baptist/Unitarian, Irish/Italian/Octogenarian/Zen Buddhist, Zionist/Seventh-day Adventist, Women's Lib/Republican, Mattachine/Four Square Gospel feels it has the will, the right, the duty to douse the kerosene, light the fuse. [...] Fire-Captain Beatty, in my novel Fahrenheit 451, described how the books were burned first by minorities, each ripping a page or a paragraph from this book, then that, until the day came when the books were empty and the minds shut and the libraries closed forever. [...] Only six weeks ago, I discovered that, over the years, some cubby-hole editors at Ballantine Books, fearful of contaminating the young, had, bit by bit, censored some seventy-five separate sections from the novel. Students, reading the novel, which, after all, deals with censorship and book-burning in the future, wrote to tell me of this exquisite irony. Judy-Lynn del Rey, one of the new Ballantine editors, is having the entire book reset and republished this summer with all the damns and hells back in place.[82]

Book-burning censorship, Bradbury would argue, was a side-effect of these two primary factors; this is consistent with Captain Beatty's speech to Montag about the history of the firemen. According to Bradbury, it is the people, not the state, who are the culprit in Fahrenheit 451.[8] Fahrenheit's censorship is not the result of an authoritarian program to retain power, but the result of a fragmented society seeking to accommodate its challenges by deploying the power of entertainment and technology. As Captain Beatty explains (p. 55)

...The bigger your market, Montag, the less you handle controversy, remember that! All the minor minorities with their navels to be kept clean."[...] "It didn't come from the Government down. There was no dictum, no declaration, no censorship, to start with, no! Technology, mass exploitation, and minority pressure carried the trick, thank God.

A variety of other themes in the novel besides censorship have been suggested. Two major themes are resistance to conformity and control of individuals via technology and mass media. Bradbury explores how the government is able to use mass media to influence society and suppress individualism through book burning. The characters Beatty and Faber point out that the American population is to blame. Due to their constant desire for a simplistic, positive image, books must be suppressed. Beatty blames the minority groups, who would take offense to published works that displayed them in an unfavorable light. Faber went further to state that, rather than the government banning books, the American population simply stopped reading on their own. He notes that the book burnings themselves became a form of entertainment for the general public.[83]

In a 1994 interview, Bradbury stated that Fahrenheit 451 was more relevant during this time than in any other, stating that, "it works even better because we have political correctness now. Political correctness is the real enemy these days. The black groups want to control our thinking and you can't say certain things. The homosexual groups don't want you to criticize them. It's thought control and freedom of speech control."[9]

Predictions for the future

[edit]Fahrenheit 451 is set in an unspecified city and time, though it is written as if set in a distant future.[note 1][25] The earliest editions make clear that it takes place no earlier than the year 2022 due to a reference to an atomic war taking place during that year.[note 5][84]

Bradbury described himself as "a preventer of futures, not a predictor of them."[85] He did not believe that book burning was an inevitable part of the future; he wanted to warn against its development.[85] In a later interview, when asked if he believes that teaching Fahrenheit 451 in schools will prevent his totalitarian[2] vision of the future, Bradbury replied in the negative. Rather, he states that education must be at the kindergarten and first-grade level. If students are unable to read then, they will be unable to read Fahrenheit 451.[86]

As to technology, Sam Weller notes that Bradbury "predicted everything from flat-panel televisions to earbud headphones and twenty-four-hour banking machines."[87]

Adaptations

[edit]Television

[edit]Playhouse 90 broadcast "A Sound of Different Drummers" on CBS in 1957, written by Robert Alan Aurthur. The play combined plot ideas from Fahrenheit 451 and Nineteen Eighty-Four. Bradbury sued and eventually won on appeal.[88][89]

Film

[edit]A film adaptation written and directed by François Truffaut and starring Oskar Werner and Julie Christie was released in 1966.[90]

A film adaptation directed by Ramin Bahrani and starring Michael B. Jordan, Michael Shannon, Sofia Boutella, and Lilly Singh was released in 2018 for HBO.[91][92]

Theater

[edit]In the late 1970s Bradbury adapted his book into a play. At least part of it was performed at the Colony Theatre in Los Angeles in 1979, but it was not in print until 1986 and the official world premiere was only in November 1988 by the Fort Wayne, Indiana Civic Theatre. The stage adaptation diverges considerably from the book and seems influenced by Truffaut's movie. For example, fire chief Beatty's character is fleshed out and is the wordiest role in the play. As in the movie, Clarisse does not simply disappear but in the finale meets up with Montag as a book character (she as Robert Louis Stevenson, he as Edgar Allan Poe).[93]

The UK premiere of Bradbury's stage adaptation was not until 2003 in Nottingham,[93] while it took until 2006 before the Godlight Theatre Company produced and performed its New York City premiere at 59E59 Theaters.[94] After the completion of the New York run, the production then transferred to the Edinburgh Festival where it was a 2006 Edinburgh Festival Pick of the Fringe.[95]

The Off-Broadway theatre The American Place Theatre presented a one man show adaptation of Fahrenheit 451 as a part of their 2008–2009 Literature to Life season.[96]

Fahrenheit 451 inspired the Birmingham Repertory Theatre production Time Has Fallen Asleep in the Afternoon Sunshine, which was performed at the Birmingham Central Library in April 2012.[97]

Radio

[edit]In 1982, Gregory Evans' radio dramatization of the novel was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 starring Michael Pennington as Montag.[98][99][100] It was broadcast eight more times on BBC Radio 4 Extra, twice each in 2010, 2012, 2013, and 2015.[101]

BBC Radio's second dramatization, by David Calcutt, was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 2003, starring Stephen Tomlin in the same role.[102]

Music

[edit]In 1984 the new wave band Scortilla released the song Fahrenheit 451 inspired by the book by R. Bradbury and the film by F. Truffaut.

Computer games

[edit]In 1984, the novel was adapted into a computer text adventure game of the same name by the software company Trillium,[103] serving as a sequel to the events of the novel, and co-written by Len Neufeld and Bradbury himself.

Comics

[edit]In June 2009, a graphic novel edition of the book was published. Entitled Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451: The Authorized Adaptation,[104] the paperback graphic adaptation was illustrated by Tim Hamilton.[105][106] The introduction in the novel is written by Bradbury himself.[107]

Cultural references

[edit]

Michael Moore's 2004 documentary Fahrenheit 9/11 refers to Bradbury's novel and the September 11 attacks, emphasized by the film's tagline "The temperature where freedom burns". The film takes a critical look at the presidency of George W. Bush, the War on Terror, and its coverage in the news media, and became the highest grossing documentary of all time.[108] Bradbury was upset by what he considered the appropriation of his title, and wanted the film renamed.[109][110] Moore filmed a subsequent documentary about the election of Donald Trump called Fahrenheit 11/9 in 2018.[111]

In 2015, the Internet Engineering Steering Group approved the publication of An HTTP Status Code to Report Legal Obstacles, now RFC 7725, which specifies that websites forced to block resources for legal reasons should return a status code of 451 when users request those resources.[112][113][114][115]

Guy Montag (as Gui Montag) is used in the 1998 real-time strategy game StarCraft as a terran firebat hero.[116]

See also

[edit]- 1953 in science fiction

- Brain rot

- Brave New World

- Burning of books and burying of scholars

- Dead Internet theory

- Dystopia

- Enshittification

- Firefighter arson

- Link rot

- Nineteen Eighty-Four

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b During Captain Beatty's recounting of the history of the firemen to Montag, he says, "Out of the nursery into the college and back to the nursery; where there's your intellectual pattern for the past five centuries or more." The text is ambiguous regarding which century he is claiming began this pattern. One interpretation is that he means the 20th century, which would place the novel in at least the 24th century. "The Fireman" novella, which was expanded to become Fahrenheit 451, is set in October 2052.

- ^ Specifically Dover Beach.

- ^ Clarisse tells Montag she is "seventeen and crazy", later admitting that she will actually be seventeen "next month".

- ^ "The Pedestrian" would go on to be published in The Reporter magazine on August 7, 1951, that is, after the publication in February 1951 of its inspired work "The Fireman".

- ^ In early editions of the book, Montag says, "We've started and won two atomic wars since 1960", in the first pages of The Sieve and the Sand. This sets a lower bound on the time setting. In later decades, some editions have changed this year to 1990 or 2022.

References

[edit]Jerrin, Neil Beeto, and G. Bhuvaneswari. "Distortion of 'Self-Image': Effects of Mental Delirium in Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury." Theory & Practice in Language Studies, vol. 12, no. 8, Aug. 2022, pp. 1634–40. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.1208.21

- ^ a b Crider, Bill (Fall 1980). Laughlin, Charlotte; Lee, Billy C. (eds.). "Ray Bradbury's FAHRENHEIT 451". Paperback Quarterly. III (3): 22. ISBN 978-1-4344-0633-0.

The first paperback edition featured illustrations by Joe Mugnaini and contained two stories in addition to the title tale: 'The Playground' and 'And The Rock Cried Out'.

- ^ a b Gerall, Alina; Hobby, Blake (2010). "Fahrenheit 451". In Bloom, Harold; Hobby, Blake (eds.). Civil Disobedience. Infobase Publishing. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-60413-439-1.

While Fahrenheit 451 begins as a dystopic novel about a totalitarian government that bans reading, the novel concludes with Montag relishing the book he has put to memory.

- ^ "Books Published Today". The New York Times: 19. October 19, 1953.

- ^ Reid, Robin Anne (2000). Ray Bradbury: A Critical Companion. Critical Companions to Popular Contemporary Writers. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 53. ISBN 0-313-30901-9.

Fahrenheit 451 is considered one of Bradbury's best works.

- ^ Seed, David (September 12, 2005). A Companion to Science Fiction. Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture. Vol. 34. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publications. pp. 491–98. ISBN 978-1-4051-1218-5.

- ^ a b Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451 audio guide. The Big Read. Archived from the original on May 24, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

Well, we should learn from history about the destruction of books. When I was fifteen years old, Hitler burned books in the streets of Berlin. And it terrified me because I was a librarian and he was touching my life: all those great plays, all that great poetry, all those wonderful essays, all those great philosophers. So, it became very personal, didn't it? Then I found out about Russia burning the books behind the scenes. But they did it in such a way that people didn't know about it. They killed the authors behind the scenes. They burned the authors instead of the books. So I learned then how dangerously [sic] it all was.

- ^ Ray Bradbury (December 4, 1956). "Ticket to the Moon (tribute to SciFi)". Biography in Sound. Narrated by Norman Rose. NBC Radio News. 27:10–27:30. Archived from the original (mp3) on February 9, 2021. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

I wrote this book at a time when I was worried about the way things were going in this country four years ago. Too many people were afraid of their shadows; there was a threat of book burning. Many of the books were being taken off the shelves at that time.

- ^ a b c Johnston, Amy E. Boyle (May 30, 2007). "Ray Bradbury: Fahrenheit 451 Misinterpreted". LA Weekly website. Archived from the original on July 9, 2019. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

Bradbury still has a lot to say, especially about how people do not understand his most famous literary work, Fahrenheit 451, published in 1953 ... Bradbury, a man living in the creative and industrial center of reality TV and one-hour dramas, says it is, in fact, a story about how television destroys interest in reading literature.

- ^ a b Bradbury Talk Likely to Feature the Unexpected Archived July 10, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Dayton Daily News, 1 October 1994, City Edition, Lifestyle/Weekendlife Section, p. 1C.

- ^ a b Aggelis, Steven L., ed. (2004). Conversations with Ray Bradbury. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi. p. xxix. ISBN 1-57806-640-9.

...[in 1954 Bradbury received] two other awards—National Institute of Arts and Letters Award in Literature and Commonwealth Club of California Literature Gold Medal Award—for Fahrenheit 451, which is published in three installments in Playboy.

- ^ Davis, Scott A. "The California Book Awards Winners 1931-2012" (PDF). Commonwealth Club of California. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 28, 2021. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ^ Nolan, William F. (May 1963). "BRADBURY: Prose Poet In The Age Of Space". The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. 24 (5). Mercury: 20.

Then there was the afternoon at Huston's Irish manor when a telegram arrived to inform Bradbury that his first novel, Fahrenheit 451, a bitterly-satirical story of the book-burning future, had been awarded a grant of $1,000 from the National Institute of Arts and Letters.

- ^ "Libertarian Futurist Society: Prometheus Awards, A Short History". Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "1954 Retro Hugo Awards". July 26, 2007. Archived from the original on July 30, 2013. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ a b "19th Annual Grammy Awards Final Nominations". Billboard. Vol. 89, no. 3. Nielsen Business Media Inc. January 22, 1976. p. 110. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ Genzlinger, Neil (March 25, 2006). "Godlight Theater's 'Fahrenheit 451' Offers Hot Ideas for the Information Age". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ Kelley, Ken (May 1996). "Playboy Interview: Ray Bradbury". Playboy. raybradbury.com. Archived from the original on August 17, 2019. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

In the movie business the Hollywood Ten were sent to prison for refusing to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee, and in the Screen Writers Guild Bradbury was one of the lonely voices opposing the loyalty oath imposed on its members.

- ^ Beley, Gene (2007). Ray Bradbury uncensored!. Lincoln, NE: iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-37364-2.

'I was angry at Senator Joseph McCarthy and the people before him, like Parnell Thomas and the House Un-American Activities Committee and Bobby Kennedy, who was part of that whole bunch', Bradbury told Judith Green, San Joe Mercury News theatre critic, in the October 30, 1993, edition. 'I was angry about the blacklisting and the Hollywood 10. I was a $100 a week screenwriter, but I wasn't scared—I was angry.'

- ^ Beley, Gene (2006). Ray Bradbury Uncensored!: The Unauthorized Biography. iUniverse. pp. 130–40. ISBN 9780595373642.

- ^ Eller, Jonathan R.; Touponce, William F. (2004). Ray Bradbury: The Life of Fiction. Kent State University Press. pp. 164–65. ISBN 9780873387798.

- ^ Reid, Robin Anne (2000). Ray Bradbury: A Critical Companion. Critical Companions to Popular Contemporary Writers. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 59. ISBN 0-313-30901-9.

- ^ Orlean, Susan (2018). The Library Book. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-4767-4018-8.

- ^ Cusatis, John (2010). Research Guide to American Literature: Postwar Literature 1945–1970. Facts on File Library of American Literature. Vol. 6 (New ed.). New York, NY: Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-3405-5.

He 'wept' when he learned at the age of nine that the ancient library of Alexandria had been burned.

- ^ Westfahl, Gary (2005). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Themes, Works, and Wonders. Vol. 3. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 1029. ISBN 9780313329531. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

Inspired by images of book burning by the Nazis and written at the height of Army-McCarthy 'Red Scare' hearings in America, Fahrenheit 451...

- ^ a b Society for the Study of Midwestern Literature (2001). Greasley, Philip A. (ed.). Dictionary of Midwestern Literature. Vol. 1, The Authors. Indiana University Press. p. 78. ISBN 9780253336095. Archived from the original on September 30, 2021. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

Fahrenheit 451 is not set in any specific locale...

- ^ De Koster, Katie, ed. (2000). Readings on Fahrenheit 451. Literary Companion Series. San Diego, CA: Greenhaven Press. p. 35. ISBN 1-56510-857-4.

Montag does not realize at first that she is gone, or that he misses her; he simply feels that something is the matter.

- ^ De Koster, Katie, ed. (2000). Readings on Fahrenheit 451. Literary Companion Series. San Diego, CA: Greenhaven Press. p. 32. ISBN 1-56510-857-4.

The Mechanical Hound is an eight-legged glass and metal contraption that serves as a surveillance tool and programmable killing machine for the firemen, to track down suspected book hoarders and readers.

- ^ De Koster, Katie, ed. (2000). Readings on Fahrenheit 451. Literary Companion Series. San Diego, CA: Greenhaven Press. p. 31. ISBN 1-56510-857-4.

Montag's new neighbor, the sixteen-year-old Clarisse, appears in only a few scenes at the beginning of the novel.

- ^ Maher, Jimmy (September 23, 2013). "Fahrenheit 451: The Book". The Digital Antiquarian. Archived from the original on April 24, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ Rogers, John (June 6, 2012). "Author of 'Fahrenheit 451', Ray Bradbury, Dies at 91". U.S. News & World Report. Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 17, 2013. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

(451 degrees Fahrenheit, Bradbury had been told, was the temperature at which texts went up in flames)

- ^ Gaiman, Neil (May 31, 2016). "Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451, and what science fiction is and does". The View from the Cheap Seats. HarperCollins. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-06-226226-4.

He called the Los Angeles fire department and asked them at what temperature paper burned. Fahrenheit 451, somebody told him. He had his title. It didn't matter if it was true or not.

- ^ Cafe, Tony. "PHYSICAL CONSTANTS FOR INVESTIGATORS". tcforensic.com.au. TC Forensic P/L. Archived from the original on January 27, 2015. Retrieved February 11, 2015.

- ^ Forest Products Laboratory (1964). "Ignition and charring temperatures of wood" (PDF). Forest Service U. S. Department of Agriculture. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 18, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ Bradbury, Ray (2006). "Preface". In Albright, Donn; Eller, Jon (eds.). Match to Flame: The Fictional Paths to Fahrenheit 451 (1st ed.). Colorado Springs, CO: Gauntlet Publications. p. 9. ISBN 1-887368-86-8.

For many years I've told people that Fahrenheit 451 was the result of my story 'The Pedestrian' continuing itself in my life. It turns out that this is a misunderstanding of my own past. Long before 'The Pedestrian' I did all the stories that you'll find in this book and forgot about them.

- ^ Bradbury, Ray (2007). Match to Flame: The Fictional Paths to Fahrenheit 451. USA: Gauntlet Pr. ISBN 978-1887368865.

- ^ "FAHRENHEIT 451". The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. 24 (5). Mercury: 23. May 1963.

Ray Bradbury calls this story, the first of the tandem, 'a curiosity. I wrote it [he says] back in 1947–48 and it remained in my files over the years, going out only a few times to quality markets like Harper's Bazaar or The Atlantic Monthly, where it was dismissed. It lay in my files and collected about it many ideas. These ideas grew large and became ...

- ^ Bradbury, Ray (May 1963). "Bright Phoenix". The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. 24 (5). Mercury: 23–29.

- ^ "About the Book: Fahrenheit 451". The Big Read. National Endowment for the Arts. Archived from the original on May 11, 2012.

- ^ Eller, Jon (2006). "Writing by Degrees: The Family Tree of Fahrenheit 451". In Albright, Donn; Eller, Jon (eds.). Match to Flame: The Fictional Paths to Fahrenheit 451 (1st ed.). Colorado Springs, CO: Gauntlet Publications. p. 68. ISBN 1-887368-86-8.

The specific incident that sparked 'The Pedestrian' involved a similar late-night walk with a friend along Wilshire Boulevard near Western Avenue sometime in late 1949.

- ^ a b c Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451 audio guide. The Big Read.

When I came out of a restaurant when I was thirty years old, and I went walking along Wilshire Boulevard with a friend, and a police car pulled up and the policeman got up and came up to us and said, 'What are you doing?'. I said, 'Putting one foot in front of the other' and that was the wrong answer but he kept saying, you know, 'Look in this direction and that direction: there are no pedestrians' but that give me the idea for 'The Pedestrian' and 'The Pedestrian' turned into Montag! So the police officer is responsible for the writing of Fahrenheit 451.

- ^ a b c De Koster, Katie, ed. (2000). Readings on Fahrenheit 451. Literary Companion Series. San Diego, CA: Greenhaven Press. p. 26. ISBN 1-56510-857-4.

- ^ De Koster, Katie, ed. (2000). Readings on Fahrenheit 451. Literary Companion Series. San Diego, CA: Greenhaven Press. p. 158. ISBN 1-56510-857-4.

He writes 'The Phoenix [sic],' which he will later develop into the short story 'The Fireman,' which will eventually become Fahrenheit 451.

- ^ Eller, Jon (2006). "Writing by Degrees: The Family Tree of Fahrenheit 451". In Albright, Donn; Eller, Jon (eds.). Match to Flame: The Fictional Paths to Fahrenheit 451 (1st ed.). Colorado Springs, CO: Gauntlet Publications. p. 68. ISBN 1-887368-86-8.

As Bradbury has often noted, 'The Pedestrian' marks the true flashpoint that exploded into 'The Fireman' and Fahrenheit 451.

- ^ Bradbury, Ray (February 1951). "The Fireman". Galaxy Science Fiction. 5. 15 (1): 4–61.

- ^ De Koster, Katie, ed. (2000). Readings on Fahrenheit 451. Literary Companion Series. San Diego, CA: Greenhaven Press. p. 164. ISBN 1-56510-857-4.

The short story which Bradbury later expanded into the novel Fahrenheit 451, was originally published in Galaxy Science Fiction, vol. 1, no. 5 (February 1951), under the title 'The Fireman.'

- ^ a b Eller, Jon (2006). "Writing by Degrees: The Family Tree of Fahrenheit 451". In Albright, Donn; Eller, Jon (eds.). Match to Flame: The Fictional Paths to Fahrenheit 451 (1st ed.). Colorado Springs, CO: Gauntlet Publications. p. 57. ISBN 1-887368-86-8.

In 1950 Ray Bradbury composed his 25,000-word novella 'The Fireman' in just this way, and three years later he returned to the same subterranean typing room for another nine-day stint to expand this cautionary tale into the 50,000-word novel Fahrenheit 451.

- ^ Bradbury, Ray (2003). Fahrenheit 451 (50th anniversary ed.). New York, NY: Ballantine Books. pp. 167–68. ISBN 0-345-34296-8.

- ^ Weller, Sam. Bradbury Chronicles.

- ^ Liptak, Andrew (August 5, 2013). "A.E. van Vogt and the Fix-Up Novel". Kirkus Reviews. Archived from the original on January 12, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- ^ Baxter, John (2005). A Pound of Paper: Confessions of a Book Addict. Macmillan. p. 393. ISBN 9781466839892.

When it published the first edition in 1953, Ballantine also produced 200 signed and numbered copies bound in Johns-Manville Quintera, a form of asbestos.

- ^ Brier, Evan (2011). A Novel Marketplace: Mass Culture, the Book Trade, and Postwar American Fiction. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 65. ISBN 9780812201444. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

Bradbury closes his 1979 'Coda' to Fahrenheit 451, one of numerous comments on the novel he has published since 1953, ...

- ^ Reid, Robin Anne (2000). Ray Bradbury: A Critical Companion. Critical Companions to Popular Contemporary Writers. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 53. ISBN 0-313-30901-9. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

In a 1982 afterword...

- ^ Tuck, Donald H. (March 1974). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy. Vol. 1: Who's Who, A–L. Chicago, Illinois: Advent. p. 62. ISBN 0-911682-20-1. LCCN 73091828.

Special edition bound in asbestos—200 copies ca. 1954, $4.00 [probably Ballantine text]

- ^ "Fahrenheit 451". Ray Bradbury Online. spaceagecity.com. Archived from the original on May 16, 2017. Retrieved September 4, 2013.

200 copies were signed and numbered and bound in 'Johns-Manville Quinterra,' an asbestos material.

- ^ De Koster, Katie, ed. (2000). Readings on Fahrenheit 451. Literary Companion Series. San Diego, CA: Greenhaven Press. p. 164. ISBN 1-56510-857-4.

A special limited-edition version of the book with an asbestos cover was printed in 1953.

- ^ Weller, Sam (2006). The Bradbury Chronicles: The Life of Ray Bradbury. HarperCollins. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-06-054584-0. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

To fulfill his agreement with Doubleday that the book be a collection rather than a novel, the first edition of Fahrenheit 451 included two additional short stories—'The Playground' and 'And the Rock Cried Out.' (The original plan was to include eight stories plus Fahrenheit 451, but Ray didn't have time to revise all the tales.) 'The Playground' and 'And the Rock Cried Out' were removed in much later printings; in the meantime, Ray had met his contractual obligation with the first edition. Fahrenheit 451 was a short novel, but it was also a part of a collection.

- ^ De Koster, Katie, ed. (2000). Readings on Fahrenheit 451. Literary Companion Series. San Diego, CA: Greenhaven Press. p. 159. ISBN 1-56510-857-4.

A serialized version of Fahrenheit 451 appears in the March, April, and May 1954 issues of Playboy magazine.

- ^ Crider, Bill (Fall 1980). Lee, Billy C.; Laughlin, Charlotte (eds.). "Reprints/Reprints: Ray Bradbury's FAHRENHEIT 451". Paperback Quarterly. III (3): 25. ISBN 9781434406330. Archived from the original on May 4, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

The censorship began with a special 'Bal-Hi' edition in 1967, an edition designed for high school students...

- ^ a b c Karolides, Nicholas J.; Bald, Margaret; Sova, Dawn B. (2011). 120 Banned Books: Censorship Histories of World Literature (Second ed.). Checkmark Books. p. 488. ISBN 978-0-8160-8232-2.

In 1967, Ballantine Books published a special edition of the novel to be sold in high schools. Over 75 passages were modified to eliminate such words as hell, damn, and abortion, and two incidents were eliminated. The original first incident described a drunk man who was changed to a sick man in the expurgated edition. In the second incident, reference is made to cleaning fluff out of the human navel, but the expurgated edition changed the reference to cleaning ears.

- ^ Burress, Lee (1989). Battle of the Books: Literary Censorship in the Public Schools, 1950–1985. Scarecrow Press. p. 104. ISBN 0-8108-2151-6.

- ^ a b c Greene, Bill (February 2007). "The mutilation and rebirth of a classic: Fahrenheit 451". Compass: New Directions at Falvey. III (3). Villanova University. Archived from the original on February 11, 2021. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- ^ a b Karolides, Nicholas J.; Bald, Margaret; Sova, Dawn B. (2011). 120 Banned Books: Censorship Histories of World Literature (Second ed.). Checkmark Books. p. 488. ISBN 978-0-8160-8232-2.

After six years of simultaneous editions, the publisher ceased publication of the adult version, leaving only the expurgated version for sale from 1973 through 1979, during which neither Bradbury nor anyone else suspected the truth.

- ^ Crider, Bill (Fall 1980). Lee, Billy C.; Laughlin, Charlotte (eds.). "Reprints/Reprints: Ray Bradbury's FAHRENHEIT 451". Paperback Quarterly. III (3): 25. ISBN 9781434406330. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

There is no mention anywhere on the Bal-Hi edition that it has been abridged, but printing histories in later Ballantine editions refer to the 'Revised Bal-Hi Editions'.

- ^ Bradbury, Ray (2005). Fahrenheit 451. Read by Christopher Hurt (Unabridged ed.). Ashland, OR: Blackstone Audiobooks. ISBN 0-7861-7627-X.

- ^ "Fahrenheit 451 becomes e-book despite author's feelings". BBC News. November 30, 2011. Archived from the original on January 6, 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- ^ Flood, Alison (November 30, 2011). "Fahrenheit 451 ebook published as Ray Bradbury gives in to digital era". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ^ Conklin, Groff (February 1954). "Galaxy's 5 Star Shelf". Galaxy Science Fiction: 108.

- ^ Derleth, August (October 25, 1953). "Vivid Prophecy of Book Burning". Chicago Sunday Tribune.

- ^ Weller, Sam (2010). Listen to the Echoes: The Ray Bradbury Interviews. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House. p. 124.

- ^ McNamee, Gregory (September 15, 2010). "Appreciations: Fahrenheit 451". Kirkus Reviews. 78 (18): 882.

- ^ "Recommended Reading", F&SF, December 1953, p. 105.

- ^ "The Reference Library", Astounding Science Fiction, April 1954, pp. 145–46

- ^ "Nothing but TV". The New York Times. November 14, 1953.

- ^ "These Are the NYPL's Top Check Outs OF ALL TIME". January 13, 2020. Archived from the original on January 13, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ "How the apartheid regime burnt books -- in their tens of thousands". October 24, 2018.

- ^ Karolides, Nicholas J.; Bald, Margaret; Sova, Dawn B. (2011). 120 Banned Books: Censorship Histories of World Literature (Second ed.). Checkmark Books. pp. 501–02. ISBN 978-0-8160-8232-2.

- ^ a b Karolides, Nicholas J.; Bald, Margaret; Sova, Dawn B. (2011). 120 Banned Books: Censorship Histories of World Literature (Second ed.). Checkmark Books. p. 489. ISBN 978-0-8160-8232-2.

In 1992, students of Venado Middle School in Irvine, California, were issued copies of the novel with numerous words blacked out. School officials had ordered teachers to use black markers to obliterate all of the 'hells', 'damns', and other words deemed 'obscene' in the books before giving them to students as required reading. Parents complained to the school and contacted local newspapers, who sent reporters to write stories about the irony of a book that condemns bookburning and censorship being expurgated. Faced with such an outcry, school officials announced that the censored copies would no longer be used.

- ^ a b Wrigley, Deborah (October 3, 2006). "Parent files complaint about book assigned as student reading". ABC News. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- ^ Ray Bradbury (December 4, 1956). "Ticket to the Moon (tribute to SciFi)" (mp3). Biography in Sound. Narrated by Norman Rose. NBC Radio News. 27:10–27:57. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ "The Definitive Biography in Sound Radio Log". Archived from the original on March 21, 2021. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- ^ Quoted by Kingsley Amis in New Maps of Hell: A Survey of Science Fiction (1960). Bradbury directly foretells this incident early in the work: "And in her ears the little Seashells, the thimble radios tamped tight, and an electronic ocean of sound, of music and talk and music and talking coming in." p.12

- ^ Bradbury, Ray (2003). Fahrenheit 451 (50th anniversary ed.). New York, NY: Ballantine Books. pp. 175–79. ISBN 0-345-34296-8.

- ^ Reid, Robin Anne (2000). Ray Bradbury: A Critical Companion. Critical Companions to Popular Contemporary Writers. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 59–60. ISBN 0-313-30901-9.

- ^ Reid, Robin Anne (2000). Ray Bradbury: A Critical Companion. Critical Companions to Popular Contemporary Writers. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 53. ISBN 0-313-30901-9.

Fahrenheit 451 is set in an unnamed city in the United States, possibly in the Midwest, in some undated future.

- ^ a b Aggelis, Steven L., ed. (2004). Conversations with Ray Bradbury. Interview by Shel Dorf. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi. p. 99. ISBN 1-57806-640-9.

I am a preventor of futures, not a predictor of them. I wrote Fahrenheit 451 to prevent book-burnings, not to induce that future into happening, or even to say that it was inevitable.

- ^ Aggelis, Steven L., ed. (2004). Conversations with Ray Bradbury. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi. p. 189. ISBN 1-57806-640-9.

- ^ Weller, Sam (2010). Listen to the Echoes: The Ray Bradbury Interviews. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House. p. 263.

- ^ Nolan, William F. (May 1963). "Bradbury: Prose Poet in the Age of Space". The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction: 7–21.

- ^ Bowie, Stephen (August 17, 2010). "The Sound of a Single Drummer". The Classic TV History Blog. wordpress.com. Archived from the original on August 31, 2013. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- ^ Frey, James N. (2010). How to Write a Damn Good Thriller: A Step-by-Step Guide for Novelists and Screenwriters (1st ed.). Macmillan. p. 255. ISBN 978-0-312-57507-6. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

FAHRENHEIT 451* (1966); written by François Truffaut from the novel by Ray Bradbury; starring Oskar Werner and Julie Christie; directed by François Truffaut.

- ^ Hipes, Patrick (April 19, 2017). "HBO's 'Fahrenheit 451' Movie: Michael B. Jordan & Michael Shannon To Star". Deadline. Archived from the original on January 21, 2020. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- ^ Ford, Rebecca (June 6, 2017). "'Mummy' Star Sofia Boutella Joins Michael B. Jordan in 'Fahrenheit 451'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ a b Fahrenheit 451 (play) Archived April 20, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, BradburyMedia; accessed September 17, 2016.

- ^ Genzlinger, Neil (March 25, 2006). "Godlight Theater's 'Fahrenheit 451' Offers Hot Ideas for the Information Age". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- ^ "The Edinburgh festival 2006 – Reviews – Theatre 'F' – 8 out of 156". Edinburghguide.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ "Literature to Life – Citizenship & Censorship: Raise Your Civic Voice in 2008–09". The American Place Theatre. Archived from the original on November 10, 2009.

- ^ Edvardsen, Mette. "Time Has Fallen Asleep In The Afternoon Sunshine Presented at Birmingham Central Library". Archived from the original on May 31, 2012. Retrieved March 22, 2013.

- ^ Nichols, Phil (October 17, 2007). "A sympathy with sounds: Ray Bradbury and BBC Radio, 1951–1970". The Radio Journal: International Studies in Broadcast and Audio Media. 4 (1, 2, 3): 111–123. hdl:2436/622705. ISSN 1476-4504. Archived from the original on November 16, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2021 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Nigel Deacon. "Ray Bradbury Radio Plays & Readings". Diversity Website. Archived from the original on June 13, 2012. Retrieved June 7, 2012.

- ^ Bradbury, Ray (November 13, 1982). Ray Bradbury: Fahrenheit 451 (Radio broadcast). BBC Radio 4. Retrieved November 16, 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 Extra - Ray Bradbury - Fahrenheit 451". BBC. Archived from the original on November 16, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ^ "The Saturday Play: Fahrenheit 451". BBC Programme Index. July 5, 2003. Archived from the original on March 11, 2021. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- ^ Merciez, Gil (May 1985). "Fahrenheit 451". Antic's Amiga Plus. 5 (1): 81.

- ^ "Macmillan: Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451: The Authorized Adaptation Ray Bradbury, Tim Hamilton: Books". Us.macmillan.com. Archived from the original on September 27, 2009. Retrieved September 21, 2009.

- ^ Neary, Lynn (July 30, 2009). "Reimagining 'Fahrenheit 451' As A Graphic Novel". All Things Considered. NPR. Archived from the original on March 17, 2014. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

- ^ Maury, Laurel (July 30, 2009). "Bradbury Classic In Vivid, 'Necessary' Graphic Form". NPR. Archived from the original on March 17, 2014. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

- ^ Minzesheimer, Bob (August 2, 2009). "Graphic novel of 'Fahrenheit 451' sparks Bradbury's approval". USA Today. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- ^ "Fahrenheit 9/11". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on October 15, 2011. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ ""Fahrenheit 451" author wants title back". Hardball with Chris Matthews. NBC News. June 29, 2004. Archived from the original on February 24, 2020. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ "Call it a tale of two 'Fahrenheits'". MSNBC. June 29, 2004. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2016.

- ^ France, Lisa Respers (May 17, 2017). "Michael Moore's surprise Trump doc: What we know". cnn.com. CNN. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- ^ Nottingham, Mark (December 21, 2015). "mnot's blog: Why 451?". Archived from the original on December 29, 2015. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- ^ "An HTTP Status Code to Report Legal Obstacles". Internet Engineering Steering Group. December 21, 2015. Archived from the original on February 29, 2016. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- ^ T. Bray (February 2016). An HTTP Status Code to Report Legal Obstacles. Internet Engineering Task Force. doi:10.17487/RFC7725. ISSN 2070-1721. RFC 7725. Proposed Standard.

Thanks also to Ray Bradbury.

- ^ "What is Error 451?". Open Rights Group. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- ^ Blizzard Entertainment. "Starcraft" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 22, 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- McGiveron, R. O. (1996). "What 'Carried the Trick'? Mass Exploitation and the Decline of Thought in Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451". Extrapolation. 37 (3). Liverpool University Press: 245–256. doi:10.3828/extr.1996.37.3.245. ISSN 0014-5483.

- McGiveron, R. O. (1996). "Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451". Explicator. 54 (3): 177–180. doi:10.1080/00144940.1996.9934107. ISSN 0014-4940.

- Smolla, Rodney A. (April 2009). "The Life of the Mind and a Life of Meaning: Reflections on Fahrenheit 451" (PDF). Michigan Law Review. 107 (6): 895–912. ISSN 0026-2234.

External links

[edit] Quotations related to Fahrenheit 451 at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Fahrenheit 451 at Wikiquote Media related to Fahrenheit 451 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Fahrenheit 451 at Wikimedia Commons- Fahrenheit 451 title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- 1953 American novels

- 1953 science fiction novels

- American novels adapted into films

- American philosophical novels

- Ballantine Books books

- Books about bibliophilia

- Books about books

- Novels about freedom of speech

- Books about television

- Dystopian novels

- Totalitarianism in fiction

- Hugo Award for Best Novel–winning works

- Metafictional novels

- American novels adapted into television shows

- Obscenity controversies in literature

- Novels about consumerism

- Novels about totalitarianism

- Novels by Ray Bradbury

- Novels set in the future

- Science fiction novels adapted into films

- Social science fiction

- Books about censorship

- Works about reading

- Works originally published in Galaxy Science Fiction

- Works subject to expurgation