Moon rock

Moon rock or lunar rock is rock originating from Earth's Moon. This includes lunar material collected during the course of human exploration of the Moon, and rock that has been ejected naturally from the Moon's surface and landed on Earth as meteorites.

Sources

[edit]Moon rocks on Earth come from four sources: those collected by six United States Apollo program crewed lunar landings from 1969 to 1972; those collected by three Soviet uncrewed Luna probes in the 1970s; those collected by the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program's uncrewed probes; and rocks that were ejected naturally from the lunar surface before falling to Earth as lunar meteorites.

Apollo program

[edit]Six Apollo missions collected 2,200 samples of material weighing 381 kilograms (840 lb),[1] processed into more than 110,000 individually cataloged samples.[2]

| Mission | Site | Sample mass returned[1] |

Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apollo 11 | Mare Tranquillitatis |

21.55 kg (47.51 lb) |

1969 |

| Apollo 12 | Ocean of Storms |

34.30 kg (75.62 lb) |

1969 |

| Apollo 14 | Fra Mauro formation |

42.80 kg (94.35 lb) |

1971 |

| Apollo 15 | Hadley–Apennine |

76.70 kg (169.10 lb) |

1971 |

| Apollo 16 | Descartes Highlands |

95.20 kg (209.89 lb) |

1972 |

| Apollo 17 | Taurus–Littrow |

110.40 kg (243.40 lb) |

1972 |

Luna program

[edit]Three Luna spacecraft returned with 301 grams (10.6 oz) of samples.[3][4][5]

| Mission | Site | Sample mass returned |

Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luna 16 | Mare Fecunditatis | 101 g (3.6 oz)[6] | 1970 |

| Luna 20 | Mare Fecunditatis | 30 g (1.1 oz)[7] | 1972 |

| Luna 24 | Mare Crisium | 170 g (6.0 oz)[8] | 1976 |

The Soviet Union abandoned its attempts at a crewed lunar program in the 1970s, but succeeded in landing three robotic Luna spacecraft with the capability to collect and return small samples to Earth. A combined total of less than half a kilogram of material was returned.

In 1993, three small rock fragments from Luna 16, weighing 200 mg, were sold for US$ 442,500 at Sotheby's (equivalent to $933,317 in 2023).[9] In 2018, the same three Luna 16 rock fragments sold for US$ 855,000 at Sotheby's.[10]

Chang'e missions

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2020) |

| Mission | Site | Sample mass returned |

Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chang'e 5 | Mons Rümker | 1,731 g (3.8 lb)[11] | 2020 |

| Chang'e 6 | Southern Apollo crater | 1,935.3 g (4.3 lb)[12][13] | 2024 |

In 2020, Chang'e 5, the fifth lunar exploration mission of the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program, returned approximately 1,731 g (61.1 oz) of rocks and dust from the Oceanus Procellarum, (the Ocean of Storms), the largest dark region on the Moon, visible on the western edge.[14] The Chang'e-5 samples contain 'perplexing combination' of minerals and include the sixth new lunar mineral, named Changesite-(Y). This phosphate mineral characterized by colorless, transparent columnar crystals.[14] Researchers estimated the peak pressure (11-40 GPa) and impact duration (0.1-1.0 second) of the collision that shaped the sample. Using shock wave models, they estimated the resulting crater to be between 3 and 32 kilometers wide, depending on the impact angle.[15]

The follow-up mission to Chang'e 5, Chang'e 6, reached the Moon on May 8, 2024, and entered lunar orbit for 20 days to find an appropriate landing site.[12] On 1 June 2024, the lander separated from the orbiter and landed on a mare unit at the southern part of the Apollo crater (36.1°S, 208.3°E).[16] The mission objective was to collect about 2 kg of material from the far side of the Moon and bring it back to Earth.

The Chang’e-6 probe withstood the high temperatures and collected the samples by drilling into the Moon's surface and scooping soil and rocks with a mechanical arm, according to a statement from the China National Space Administration (CNSA). The collected rock was crushed, melted and drawn into filaments about one third of the diameter of a human hair, then spun into thread and woven into cloth. "The lunar surface is rich in basalt and since we're building a lunar base in the future, we will most likely have to make basalt into fibers and use it as building materials," said engineer Zhou Changyi.[17]

The samples were placed in the ascent vehicle, which docked with the Chang'e 6 orbiter-return vehicle on June 6, 2024[12] China's Chang'e 6 lunar probe, carrying the first lunar rocks ever collected from the far side of the Moon, landed in China's Inner Mongolia region on June 25, 2024.

Lunar meteorites

[edit]More than 370 lunar meteorites have been collected on Earth,[18] representing more than 30 different meteorite finds (no falls), with a total mass of over 1,090 kilograms (2,400 lb).[19] Some were discovered by scientific teams (such as ANSMET) searching for meteorites in Antarctica, with most of the remainder discovered by collectors in the desert regions of northern Africa and Oman. A Moon rock known as "NWA 12691", which weighs 13.5 kilograms (30 lb), was found in the Sahara Desert at the Algerian and Mauritanian borders in January 2017,[20] and went on sale for $2.5 million in 2020.[21]

Dating

[edit]Rocks from the Moon have been measured by radiometric dating techniques. They range in age from about 3.16 billion years old for the basaltic samples derived from the lunar maria, up to about 4.44 billion years old for rocks derived from the highlands.[22] Based on the age-dating technique of "crater counting," the youngest basaltic eruptions are believed to have occurred about 1.2 billion years ago,[23] but scientists do not possess samples of these lavas. In contrast, the oldest ages of rocks from the Earth are between 3.8 and 4.28 billion years.

Composition

[edit]| Mineral | Elements | Lunar rock appearance |

|---|---|---|

| Plagioclase feldspar | Calcium (Ca) Aluminium (Al) Silicon (Si) Oxygen (O) |

White to transparent gray; usually as elongated grains. |

| Pyroxene | Iron (Fe), Magnesium (Mg) Calcium (Ca) Silicon (Si) Oxygen (O) |

Maroon to black; the grains appear more elongated in the maria and more square in the highlands. |

| Olivine | Iron (Fe) Magnesium (Mg) Silicon (Si) Oxygen (O) |

Greenish color; generally, it appears in a rounded shape. |

| Ilmenite | Iron (Fe), Titanium (Ti) Oxygen (O) |

Black, elongated square crystals. |

Moon rocks fall into two main categories: those found in the lunar highlands (terrae), and those in the maria. The terrae consist dominantly of mafic plutonic rocks. Regolith breccias with similar protoliths are also common. Mare basalts come in three distinct series in direct relation to their titanium content: high-Ti basalts, low-Ti basalts, and Very Low-Ti (VLT) basalts.

Almost all lunar rocks are depleted in volatiles and are completely lacking in hydrated minerals common in Earth rocks. In some regards, lunar rocks are closely related to Earth's rocks in their isotopic composition of the element oxygen. The Apollo Moon rocks were collected using a variety of tools, including hammers, rakes, scoops, tongs, and core tubes. Most were photographed prior to collection to record the condition in which they were found. They were placed inside sample bags and then a Special Environmental Sample Container for return to the Earth to protect them from contamination. In contrast to the Earth, large portions of the lunar crust appear to be composed of rocks with high concentrations of the mineral anorthite. The mare basalts have relatively high iron values. Furthermore, some of the mare basalts have very high levels of titanium (in the form of ilmenite).[25]

Highlands rocks

[edit]

| Plagioclase | Pyroxene | Olivine | Ilmenite | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anorthosite | 90% | 5% | 5% | 0% |

| Norite | 60% | 35% | 5% | 0% |

| Troctolite | 60% | 5% | 35% | 0% |

Primary igneous rocks in the lunar highlands compose three distinct groups: the ferroan anorthosite suite, the magnesian suite, and the alkali suite.

Lunar breccias, formed largely by the immense basin-forming impacts, are dominantly composed of highland lithologies because most mare basalts post-date basin formation (and largely fill these impact basins).

- The ferroan anorthosite suite consists almost exclusively of the rock anorthosite (>90% calcic plagioclase) with less common anorthositic gabbro (70-80% calcic plagioclase, with minor pyroxene). The ferroan anorthosite suite is the most common group in the highlands, and is inferred to represent plagioclase flotation cumulates of the lunar magma ocean, with interstitial mafic phases formed from trapped interstitial melt or rafted upwards with the more abundant plagioclase framework. The plagioclase is extremely calcic by terrestrial standards, with molar anorthite contents of 94–96% (An94–96). This reflects the extreme depletion of the bulk Moon in alkalis (Na, K) as well as water and other volatile elements. In contrast, the mafic minerals in this suite have low Mg/Fe ratios that are inconsistent with calcic plagioclase compositions. Ferroan anorthosites have been dated using the internal isochron method at circa 4.4 Ga.

- The magnesian suite (or "Mg-suite") consists of dunites (>90% olivine), troctolites (olivine-plagioclase), and gabbros (plagioclase-pyroxene) with relatively high Mg/Fe ratios in the mafic minerals and a range of plagioclase compositions that are still generally calcic (An86–93). These rocks represent later intrusions into the highlands crust (ferroan anorthosite) at round 4.3–4.1 Ga. An interesting aspect of this suite is that analysis of the trace element content of plagioclase and pyroxene requires equilibrium with a KREEP-rich magma, despite the refractory major element contents.

- The alkali suite is so-called because of its high alkali content—for Moon rocks. The alkali suite consists of alkali anorthosites with relatively sodic plagioclase (An70–85), norites (plagioclase-orthopyroxene), and gabbronorites (plagioclase-clinopyroxene-orthopyroxene) with similar plagioclase compositions and mafic minerals more iron-rich than the magnesian suite. The trace element content of these minerals also indicates a KREEP-rich parent magma. The alkali suite spans an age range similar to the magnesian suite.

- Lunar granites are relatively rare rocks that include diorites, monzodiorites, and granophyres. They consist of quartz, plagioclase, orthoclase or alkali feldspar, rare mafics (pyroxene), and rare zircon. The alkali feldspar may have unusual compositions unlike any terrestrial feldspar, and they are often Ba-rich. These rocks apparently form by the extreme fractional crystallization of magnesian suite or alkali suite magmas, although liquid immiscibility may also play a role. U-Pb date of zircons from these rocks and from lunar soils have ages of 4.1–4.4 Ga, more or less the same as the magnesian suite and alkali suite rocks. In the 1960s, NASA researcher John A. O'Keefe and others linked lunar granites with tektites found on Earth although many researchers refuted these claims. According to one study, a portion of lunar sample 12013 has a chemistry that closely resembles javanite tektites found on Earth.[citation needed]

- Lunar breccias range from glassy vitrophyre melt rocks, to glass-rich breccia, to regolith breccias. The vitrophyres are dominantly glassy rocks that represent impact melt sheets that fill large impact structures. They contain few clasts of the target lithology, which is largely melted by the impact. Glassy breccias form from impact melt that exit the crater and entrain large volumes of crushed (but not melted) ejecta. It may contain abundant clasts that reflect the range of lithologies in the target region, sitting in a matrix of mineral fragments plus glass that welds it all together. Some of the clasts in these breccias are pieces of older breccias, documenting a repeated history of impact brecciation, cooling, and impact. Regolith breccias resemble the glassy breccias but have little or no glass (melt) to weld them together. As noted above, the basin-forming impacts responsible for these breccias pre-date almost all mare basalt volcanism, so clasts of mare basalt are very rare. When found, these clasts represent the earliest phase of mare basalt volcanism preserved.

Mare basalts

[edit]| Plagioclase | Pyroxene | Olivine | Ilmenite | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High titanium content | 30% | 54% | 3% | 18% |

| Low titanium content | 30% | 60% | 5% | 5% |

| Very low titanium content | 35% | 55% | 8% | 2% |

Mare basalts are named as such because they frequently constitute large portions of the lunar maria. These typically contain 18–21 percent FeO by weight, and 1–13 percent TiO2. They are similar to terrestrial basalts, but have many important differences; for example, mare basalts show a large negative europium anomaly. The type location is Mare Crisium sampled by Luna 24.

- KREEP Basalts (and borderline VHK (Very High K) basalts) have extraordinary potassium content. These contain 13–16 percent Al2O3, 9–15 percent FeO, and are enriched in magnesium and incompatible elements (potassium, phosphorus and rare earth elements) 100–150 times compared to ordinary chondrite meteorites.[26] These are commonly encountered around the Oceanus Procellarum, and are identified in remote sensing by their high (about 10 ppm) thorium contents. Most of incompatible elements in KREEP basalts are incorporated in the grains of the phosphate minerals apatite and merrillite.[27]

Curation and availability

[edit]

The main repository for the Apollo Moon rocks is the Lunar Sample Laboratory Facility at the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. For safekeeping, there is also a smaller collection stored at White Sands Test Facility in Las Cruces, New Mexico. Most of the rocks are stored in nitrogen to keep them free of moisture. They are handled only indirectly, using special tools.

Some Moon rocks from the Apollo missions are displayed in museums, and a few allow visitors to touch them. One of these, called the Touch Rock, is displayed in the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.[28] The idea of having touchable Moon rocks at a museum was suggested by Apollo scientist Farouk El-Baz, who was inspired by his childhood pilgrimage to Mecca where he touched the Black Stone (which in Islam is believed to be sent down from the heavens).[29]

Moon rocks collected during the course of lunar exploration are currently considered priceless.[28] In 2002, a safe was stolen from the Lunar Sample Building that contained minute samples of lunar and Martian material. The samples were recovered, and NASA estimated their value during the ensuing court case at about $1 million for 10 oz (280 g) of material.[citation needed]

Naturally transported Moon rocks in the form of lunar meteorites are sold and traded among private collectors.[citation needed]

Goodwill Moon rocks

[edit]

Apollo 17 astronauts Eugene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt picked up a rock "composed of many fragments, of many sizes, and many shapes, probably from all parts of the Moon". This rock was later labeled sample 70017.[30] President Nixon ordered that fragments of that rock should be distributed in 1973 to all 50 US states and 135 foreign heads of state. The fragments were presented encased in an acrylic sphere, mounted on a wood plaque which included the recipients' flag which had also flown aboard Apollo 17.[31] Many of the presentation Moon rocks are now unaccounted for, having been stolen or lost.

Discoveries

[edit]Three minerals were discovered from the Moon: armalcolite, tranquillityite, and pyroxferroite. Armalcolite was named for the three astronauts on the Apollo 11 mission: Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins.

Stolen and missing Moon rocks

[edit]Because of their rarity on Earth and the difficulty of obtaining more, Moon rocks have been frequent targets of theft and vandalism, and many have gone missing or were stolen.

Gallery

[edit]-

A visitor touching a lunar sample at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex

-

NASA Lunar sample 15555 on display at Space Center Houston Lunar Samples Vault, at NASA's Johnson Space Center

-

NASA Lunar sample 15498 on display at Space Center Houston Lunar Samples Vault, at NASA's Johnson Space Center

-

NASA Lunar sample 60015 on display at Space Center Houston Lunar Samples Vault, at NASA's Johnson Space Center

-

NASA Lunar sample 60016 on display at Space Center Houston Lunar Samples Vault, at NASA's Johnson Space Center

-

NASA Lunar Sample Return Container with Lunar soil on display at Space Center Houston Lunar Samples Vault, at NASA's Johnson Space Center

-

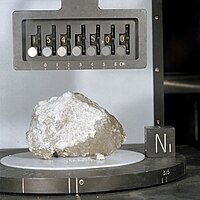

Lunar Ferroan Anorthosite #60025 (Plagioclase Feldspar). Collected by Apollo 16 from the Lunar Highlands near Descartes Crater. This sample is currently on display at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC

-

Samples in Lunar Sample Building at JSC

-

Moon rock on display for visitors to touch at the Apollo/Saturn V Center

-

Sample collection case, containing collection bags for use on the surface, at the National Museum of Natural History

-

Tongs used to pick up Moon rocks

-

A piece of regolith from Apollo 11 presented to the Soviet Union and exhibited in the Memorial Museum of Cosmonautics in Moscow.

-

Apollo 17 "Goodwill Moonrock"

-

Cut fragment of Apollo 17 sample 76015, an impact melt breccia

-

Sample 15016, the Seatbelt basalt

-

Apollo 16's sample 61016, better known as Big Muley, is the largest sample collected during the Apollo program

-

Big Bertha, collected on Apollo 14, is among the largest rock samples returned from the Moon (nearly 9 kilograms)

-

Moon rocks on display at the National Museum of China

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Orloff, Richard W. (September 2004) [First published 2000]. "Extravehicular Activity". Apollo by the Numbers: A Statistical Reference. The NASA History Series. Washington, D.C.: NASA History Division, Office of Policy and Plans. ISBN 978-0-16-050631-4. LCCN 00061677. NASA SP-2000-4029. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ "NASA Lunar Sample Laboratory Facility". NASA Curation Lunar. NASA. September 1, 2016. Archived from the original on August 25, 2018. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

- ^ Ivankov, A. "Luna 16". National Space Science Data Center Catalog. NASA. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

The drill was deployed and penetrated to a depth of 35 cm before encountering hard rock or large fragments of rock. The column of regolith in the drill tube was then transferred to the soil sample container... the hermetically sealed soil sample container, lifted off from the Moon carrying 101 grams of collected material

- ^ Ivankov, A. "Luna 20". National Space Science Data Center Catalog. NASA. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

Luna 20 was launched from the lunar surface on 22 February 1972 carrying 30 grams of collected lunar samples in a sealed capsule

- ^ Ivankov, A. "Luna 24". National Space Science Data Center Catalog. NASA. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

the mission successfully collected 170.1 grams of lunar samples and deposited them into a collection capsule

- ^ "NASA - NSSDC - Spacecraft - Details". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- ^ "NASA - NSSDC - Spacecraft - Details". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- ^ "NASA - NSSDC - Spacecraft - Details". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- ^ Van Gelder, Lawrence (December 2, 1995). "F.B.I. Revisits Earthly Theft of Moon Rock". The New York Times. Retrieved September 6, 2021.

- ^ "THE ONLY KNOWN DOCUMENTED SAMPLES OF THE MOON AVAILABLE FOR PRIVATE OWNERSHIP". Sothebys.com. November 29, 2018.

- ^ "China's Chang'e-5 retrieves 1,731 grams of moon samples". Xinhua News Agency. December 19, 2020. Archived from the original on December 20, 2020. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- ^ a b c "NASA - NSSDCA - Spacecraft - Details". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "新华社权威快报丨嫦娥六号带回世界首份月背样品1935.3克" (in Simplified Chinese). 新华网. June 28, 2024. Retrieved June 28, 2024.

- ^ a b Sharmila Kuthunur (February 8, 2024). "China's Chang'e-5 moon samples contain 'perplexing combination' of minerals". Space.com. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ Nielsen, Marissa (February 6, 2024). "Understanding the Moon's History with Chang'e-5 Sample". AIP Publishing LLC. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "First Look: Chang'e 6". www.lroc.asu.edu. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ McCarthy, Nectar Gan, Simone (June 4, 2024). "China's Chang'e-6 probe lifts off with samples from moon's far side in historic first". CNN. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Meteoritical Bulletin Database — Lunar Meteorite search results". Meteoritical Bulletin Database. The Meteoritical Society. July 10, 2019. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ "List of Lunar Meteorites - Feldspathic to Basaltic Order". meteorites.wustl.edu. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ "Northwest Africa 12691". The Meteoritical Society.

- ^ "Super-Rare Moon Meteorite Found In Sahara Desert Goes On Sale For $2.5 Million". Forbes. May 2, 2020.

- ^ James Papike; Grahm Ryder & Charles Shearer (1998). "Lunar Samples". Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 36: 5.1 – 5.234.

- ^ Hiesinger, H.; Head, J. W.; Wolf, U.; Jaumann, R.; Neukum, G. (2003). "Ages and stratigraphy of mare basalts in Oceanus Procellarum, Mare Numbium, Mare Cognitum, and Mare Insularum". J. Geophys. Res. 108 (E7): 5065. Bibcode:2003JGRE..108.5065H. doi:10.1029/2002JE001985.

- ^ a b c "Exploring the Moon – A Teacher's Guide with Activities, NASA EG-1997-10-116 - Rock ABCs Fact Sheet" (PDF). NASA. November 1997. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- ^ Bhanoo, Sindya N. (December 28, 2015). "New Type of Rock Is Discovered on Moon". New York Times. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- ^ Wieczorek, Mark; Jolliff, Bradley; Khan, Amir; et al. (2006). "The Constitution and Structure of the Lunar Interior". Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 60 (1): 221–364. Bibcode:2006RvMG...60..221W. doi:10.2138/rmg.2006.60.3.

- ^ Lucey, Paul; Korotev, Randy; Taylor, Larry; et al. (2006). "understanding the lunar surface and Space-Moon Interactions". Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 60 (1): 100. Bibcode:2006RvMG...60...83L. doi:10.2138/rmg.2006.60.2.

- ^ a b Grossman, Lisa (July 15, 2019). "How NASA has kept Apollo Moon rocks safe from contamination for 50 years". Science News. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- ^ Reichhardt, Tony (June 7, 2019). "Twenty People Who Made Apollo Happen". Air & Space/Smithsonian. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- ^ Astromaterials Research & Exploration Science. "70017 Ilmenite Basalt" (PDF). NASA.

- ^ "Where are the Apollo 17 Goodwill Moon Rocks?". Collect Space.

General sources

[edit]- Marc Norman (April 21, 2004). "The Oldest Moon Rocks". Planetary Science Research Discoveries.

- Paul D. Spudis, The Once and Future Moon, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1996, ISBN 1-56098-634-4.

External links

[edit]- Rocks & Soils from the Moon—Johnson Space Center

- Apollo Geology Tool Catalog Archived September 28, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Lunar meteorites Archived April 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine—Washington University, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences

- Lunar Samples Lunar and Planetary Institute

- Articles about Moon rocks in Planetary Science Research Discoveries educational journal

- Where Today are the Apollo 11 Lunar Sample Displays? collectSPACE

- Where Today are the Apollo 17 Goodwill Moon Rocks? collectSPACE

- Kentucky's lunar sample displays in the Kentucky Historical Society objects catalog: Apollo 11, Apollo 17