Transylvanian School

| History of Romania |

|---|

|

|

|

The Transylvanian School (Romanian: Școala Ardeleană) was a cultural movement which was founded after part of the Romanian Orthodox Church in Habsburg-ruled Transylvania accepted the leadership of the pope and became the Greek-Catholic Church (c. 1700). The links with Rome brought to the Romanian Transylvanians the ideas of the Age of Enlightenment. The Transylvanian School's major centres were in the cities of Blaj (Balázsfalva), Oradea (Nagyvárad), Lugoj (Lugos) and Beiuș (Belényes).

Name

[edit]

The name Transylvanian School (Romanian: Școala Ardeleană) was not used contemporarily even though its members had a sense of belonging to a group. The literary historian Ovid Densusianu, along with Sextil Pușcariu, preferred the use of școala latinistă (Latin School) or școala transilvăneană. The latter also used the expression direcția latinistă (Latin Direction), and in a similar manner the Italian Romance scholar, Mario Ruffini, wrote of la scuola latinista rumena. Eventually, although the debate along the correct name and implicitly the nature and influence of the movement continued with scholars such as Nicolae Iorga and Lucian Blaga, the syntagm Școala ardeleană translated as "Transylvanian School" prevailed, and it is sometimes used for post-Enlightenment scholars and ideas influenced by the Transylvanian School and originating from Transylvania.[1]

Background

[edit]Prior to 18th century the Orthodox Church in Transylvania, to which most Romanians belonged to, was not recognized among the privileged estates:

The privileges define the status of the three recognized nations – the Hungarians, the Siculi and the Saxons – and the four churches – Lutheran, Calvinist, Unitarian and Catholic. The exclusion concerns the Romanian community and its Orthodox Church, a community that accounts for at least 50% of the population in the mid-eighteenth century.[2]

The situation created a favorable situation for the work of Jesuit missionaries and the efforts of the Catholic Hapsburg Empire to discuss the union of the Orthodox communities with the Catholic Church. The act became official in 1698 when the Orthodox metropolitan Atanasie Anghel of Transylvania along with 38 protopopes aligned themselves and their communities with Rome.[3][4]

In this context, the origins of the Transylvanian School go back in time to the activity of Inocențiu Micu-Klein, Gherontie Cotore, Grigorie Maior, and Petru Pavel Aaron, all members of the Greco-Catholic clergy in 18th century Transylvania[5] who in their quality of members of the Transylvanian Diet addressed the issue of political rights for Romanians in Transylvania.[6]

Activity

[edit]

Within a span of fifty years, the majority national group in the Principality of Transylvania, the Romanians, succeeded in documenting their Latin origins, rewriting their history, language, and grammar, and building the pedagogical foundation needed to educate and gain political rights for its members within the Habsburg Empire. Its members contemplated the origin of Romanians from a scientific point of view, bringing historical and philological arguments in favour of the thesis that the Transylvanian Romanians were the direct descendants of the Roman colonists brought in Dacia after its conquest in early 2nd century AD. The historical discourse and all the contributions of the Transylvanian School had a purpose, a program pursued and gradually put into practice by three generations of Romanian Transylvanian intellectuals. It was a project devised by the generation of Gherontie Cotore and Grigorie Maior, yet started by Samuil Micu-Klein. Micu-Klein gradually gathered and systematized the internal chronicles and the general plan of the historical discourse of the Transylvanian School in his works, "Brevis Historia Notitia" (Short historical notice), "Scurtã cunoștințã a istoriei românilor" (Brief presentation of the history of the Romanians), "Istoria românilor cu întrebãri și rãspunsuri" (A history of the Romanians with questions and answers), and the ample synthesis "Istoria românilor" (History of the Romanians).[7]

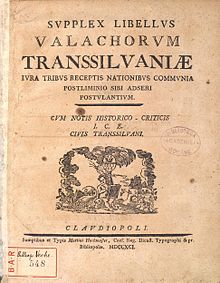

Micu-Klein, Gheorghe Șincai, Petru Maior and Ion Budai-Deleanu, who were members of the Transylvanian School during the era of Romanian national awakening, emphasised the ancient purely Latin origin of Romanians.[8] In 1791, they contributed in the memorandum: "Supplex Libellus Valachorum Transsilvaniae". In this memorandum, they demanded similar rights for the Transylvanian Romanians as those enjoyed by the (largely) Hungarian nobility, the enfranchised Saxon patrician class,[9] and the free military Székelys[10] under the Union of the Three Nations.[11] This document was presented to Emperor Leopold II by the Transylvanian School.[12]

One of the major contributions of the School was the writing and publication of the first Romanian grammar, Elementa linguae daco-romanae sive valachicae, a book that is considered the starting point of Modern Romanian language.[13] Another significant contribution to linguistics was the dictionary known as The Lexicon of Buda, a starting point of Romanian modern lexicography, printed in 1825 with the title: Lesicon românesc-lătinesc-unguresc-nemțesc care de mai mulți autori, în cursul a trizeci și mai multor ani s-au lucrat seu Lexicon Valachico-LatinoHungarico-Germanicum, quod a pluribus auctoribus decursu triginta et amplius annorum elaboratum est (translated to English as "Romanian-Latin-Hungarian-German Lexicon, elaborated by thirty authors over more than thirty years").[14][15]

The Transylvanian School created the current phonetic system of the Romanian alphabet based on the Latin alphabet, first used in the Book of Prayers by Micu-Klein and referred to as the etymological alphabet by language historians but they later had to accept the use of graphemes specific to Italian writing (such as ce, ci, ge, gi or che, chi, ghe, ghi) and diacritics (mainly ș and ț).[16] This replaced the use of the medieval Romanian Cyrillic alphabet as well as the previously Latin alphabet based phonetic system which had been based on the Hungarian alphabet. Its members, in particular Petru Maior, viewed the usage of the Cyrillic alphabet as detrimental to the very literacy of Romanians:[15]

"Everyone agrees, thus, to the fact that the Cyrillic letters that brought a deep darkness upon Romanian language need to be eradicated from the literary republic of Romanians"

Influence

[edit]The Transylvanian School marks the beginnings of modern Romanian culture, contributing to the national awakening of Romania. Their ideas and writings influenced latter Romanian scholars, some of whom activated in neighbouring Wallachia and Moldavia: Aaron Florian, Alexandru Papiu Ilarian, August Treboniu Laurian.[17]

The Transylvanian School believed that the Romanians and the Aromanians were part of the same ethnic group.[18] Its teachings influenced some prominent Aromanian figures such as Nicolae Ianovici[19] or Gheorghe Constantin Roja.

Criticism

[edit]While considered founders and civilizing force in the cultural domain by Titu Maiorescu (himself related to Petru Maior) and the members of Junimea, the Transylvanian School and later "latinists" scholars were criticised for their reliance on German and Latin loanwords.[20]

Contemporary thinkers, such as Mihail Kogălniceanu and Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu, as well as later academicians criticised the abusive "purification" of the language proposed at various extents by the School and some of the later scholars influenced by it.[21] Another contemporary, Ion Heliade Rădulescu, although himself influenced by the School in his early years of activity, vividly criticised the School's insistence of using an etymological spelling and analogical adaptations of words directly from Latin.[22]

The harshest criticism came however during the Communist Regime when the rivalry between Romanian Orthodox Church and Romanian Greek Catholic Church was employed politically, with the Greek Catholics being accused as far as being "non-Romanian agents of the West", or even as "Hungarians" since the latter were seen as Catholics. The hostility escalated to marginalization of public figures such as the Greek Catholic bishops and clerics from regional history. The Transylvanian School, as a group affiliated originally with the Greek Catholic Church, was dethroned as the main political movement that contributed to Romanian national identity in favour of a "nationalist Orthodox resilience that enabled the Romanian population to survive centuries of foreign rule".[23]

Notable members

[edit]Scholars influenced by the Transylvanian School

[edit]- Ioan Monorai

- Paul Iorgovici

- Aaron Florian

- Alexandru Papiu Ilarian

- Timotei Cipariu

- August Treboniu Laurian

- George Bariț

- Titu Maiorescu

- Simion Bărnuțiu

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Pavel, Eugen (2018). "The Transylvanian School - Premises Underlying the Critical Editions of Texts". Academia.edu. pp. 1–4. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ^ "Les privilèges définissent le statut des trois nations reconnues – les Hongrois, les Sicules et les Saxons – et des quatres Eglises – luthérienne, calvinistes, unitarienne et catholique. L'exclusion porte sur la communauté roumaine et son église orthodoxe, une communauté qui représente au moins 50% de la population vers le milieu du XVIIIe siècle." In Catherine Durandin, Histoire des Roumains, Librairie Artheme Fayard, Paris, 1995

- ^ "Uniate Churches". encyclopedia.com. 7 August 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ Miron, Greta-Monica (2007). Biserica Greco-Catolică din Comitatul Cluj în secolil al XVIII-lea (in Romanian). Cluj-Napoca: Presa Universitară Clujeană. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-973-610-553-1.

- ^ Pavel, Eugen (2018). "The Transylvanian School - Premises Underlying the Critical Editions of Texts". Academia.edu. p. 4. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ^ "Uniate Churches". encyclopedia.com. 7 August 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ Laura Stanciu, "Transylvanian Review. Vol. XXX, No.2: Petru Maior, the Transylvanian School Influencer ", (2021), pp. 3-18.

- ^ Turda, Marius (2011). "Historical Writing in the Balkans". In Macintyre, Stuart (ed.). The Oxford History of Historical Writing: Volume 4: 1800-1945. Oxford University Press. p. 352. ISBN 9780191804359.

- ^ Mircea Dogaru; Mihail Zahariade (1996). History of the Romanians: From the origins to the modern age, Volume 1 of History of the Romanians, History of the Romanians. Amco Press. p. 148. ISBN 9789739675598.

- ^ László Fosztó: Ritual Revitalisation After Socialism: Community, Personhood, and Conversion among Roma in a Transylvanian Village, Halle-Wittenberg, 2007 [1]

- ^ Marcel Cornis-Pope; John Neubauer (2004). History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe: Junctures and Disjunctures in the 19th and 20th Centuries, Volume 2. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 255. ISBN 9789027234537.

- ^ Cristian Romocea (2011). Church and State: Religious Nationalism and State Identification in Post-Communist Romania. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 112. ISBN 9781441137470.

- ^ Pană Dindelegan, Gabriela, The Grammar of Romanian, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0-19-964492-6, page 4.

- ^ Celac, Victor; Moroianu, Cristian (2018). Sala, Marius; Sarmandu, Nicolae (eds.). "Lingvistica românească" [Romanian Linguistics]. Academia.edu (in Romanian). "Etimologie" chapter. Retrieved 25 September 2024.

- ^ a b Harhătă, Bogdan; Aldea, Maria; Vremir, Lilla Marta; Leucuța, Daniel-Corneliu (December 2020). "The Lexicon of Buda. A Glimpse into the Beginnings of Mainstream Romanian Lexicography" (PDF). Euralex.org. Retrieved 25 September 2024.

- ^ Chivu, Gheorghe (6 August 2023). "The Transylvanian School - A new Assessment" (PDF). diversite.eu. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ^ Kellogg, Frederick (13 June 2020). "A history of Romanian historical writing". Academia.edu. pp. 27–28. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- ^ Lascu, Stoica (2017). "Intelectuali transilvăneni, moldoveni și "aurelieni" despre românii din Balcani (anii '30-'40 ai secolului al XIX-lea" (PDF). Annals of the Academy of Romanian Scientists: Series on History and Archaeology Sciences (in Romanian). 9 (2): 5–27. ISSN 2067-5682.

- ^ Dumbrăvescu, Nicolae (2014). "Nicolae Ianovici, un deschizător de conștiință națională la aromânii din Imperiul Habsburgic". Astra Salvensis (in Romanian). 2 (3): 52–54.

- ^ Cornis-Pope, Marcel; Neubauer, John (2010). History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe, vol 2. John Benjamins. p. 255. ISBN 9789027234582.

- ^ Boia, Lucian (2001). History and Myth in Romanian Consciousness. Central European University Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-963-9116-97-9.

- ^ Chivu, Gheorghe (6 August 2023). "The Transylvanian School - A new Assessment" (PDF). diversite.eu. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ^ Romoncea, Cristian (2011). Church and State: Religious Nationalism and State Identification in Post-Communist Romania. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 112–119.