Hannibal's crossing of the Alps

| Hannibal's crossing of the Alps | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Punic War | |||||||

Hannibal's route to Italy | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

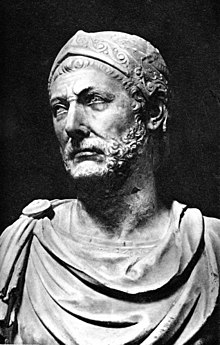

Hannibal Hasdrubal Mago Hasdrubal Gisco Syphax Hanno Hasdrubal the Bald Hampsicora Maharbal |

Publius Cornelius Scipio Tiberius S. Longus | ||||||

Hannibal's crossing of the Alps in 218 BC was one of the major events of the Second Punic War, and one of the most celebrated achievements of any military force in ancient warfare.[1]

Hannibal led his Carthaginian army over the Alps and into Italy to take the war directly to the Roman Republic, bypassing Roman and allied land garrisons, and Roman naval dominance.

The two primary sources for the event are Polybius and Livy, who were born c.20 years and c.160 years after the event, respectively.[2] The Alps were not well-documented at the time, and no archaeological evidence is available, so all modern theories depend on interpreting the three place names used by Polybius (Island, Skaras, and Allobroges) and Livy's wider range of tribe and place names, and comparing them with modern geographical knowledge.[2]

Background

After the final Carthaginian naval defeat at the Aegates Islands,[3] the Carthaginians surrendered in the First Punic War.[4] Hamilcar Barca (Barca meaning lightning),[5] a leading member of the patriotic Barcine party in Carthage and a general in the First Punic War, sought to remedy the losses that Carthage had suffered in Sicily to the Romans.[6][7] In addition to this, the Carthaginians, and Hamilcar personally,[8] were embittered by the loss of Sardinia.

After the Carthaginians' loss of the war, the Romans imposed terms that were designed to reduce Carthage to a tribute-paying city to Rome and simultaneously strip it of its fleet.[9] While the terms of the peace treaty were harsh, the Romans did not strip Carthage of its strength; Carthage was the most prosperous maritime trading port of its day, and the tribute imposed by the Romans was easily paid off on a yearly basis, while Carthage was simultaneously engaged by Carthaginian mercenaries who were in revolt.[9]

The Carthaginian Barcine party was interested in conquering Iberia, a land whose natural resources would provide needed revenue[10] and replace the resources of Sicily that, following the end of the First Punic War, were now flowing to the Romans. It was the ambition of the Barcas, one of the leading noble families of the patriotic party, to establish the Iberian peninsula as a base of operations for waging a war of revenge against the Roman military alliance. Those two factors went together, and in spite of conservative opposition to his expedition, Hamilcar set out in 238 BC[10][11][12] to begin his conquest of the Iberian peninsula with these objectives in mind. Marching west from Carthage[13] towards the Pillars of Hercules,[14] where his army crossed the strait and proceeded to subdue the peninsula, in the course of nine years[11][12][14] Hamilcar conquered the south-eastern portion of the peninsula.[11] His administration of the newly conquered provinces led Cato the Elder to remark that "there was no king equal to Hamilcar Barca."[15][better source needed]

In 228 BC,[11] Hamilcar was killed, witnessed by Hannibal,[16] during a campaign against the Celtic natives of the peninsula.[12] The commanding naval officer, who was both Hamilcar's son in law[12] and a member of the Patriotic party – Hasdrubal "The Handsome"[11][12] – was awarded the chief command by the officers of the Carthaginian Iberian army.[12][17] There were a number of Grecian colonies along the eastern coast of the Iberian peninsula, the most notable being the trade emporium of Saguntum.[17] These colonies expressed concern about the consolidation of Carthaginian power on the peninsula, which Hasdrubal's deft military leadership and diplomatic skill[14] procured. For protection, Saguntum turned to Rome; Rome sent a garrison to the city and a diplomatic mission to Hasdrubal's camp in Cartagena,[17] informing him that the Iberus (modern day Ebro) river must be the limit of the Carthaginian advance in Spain.[14][18] The conclusion of the treaty and the embassy were sent to Hasdrubal's camp in 226 BC.[18][19]

In 221 BC,[16] Hasdrubal was killed by an assassin.[20][21][22] It was in that year that the officers of the Carthaginian army in Iberia expressed their high opinion of Hamilcar's 26-year-old[23] son, Hannibal,[22] by electing him to the chief command of the army.[16][20] Having assumed the command (retroactively confirmed by the Carthaginian Senate)[20] of the army that his father had wielded through nine years of hard mountain fighting, Hannibal declared that he was going to finish his father's project of conquering the Iberian peninsula, which had been the first objective in his father's plan to bring a war to Rome in Italy, and defeat it there.

Hannibal spent the first two years of his command seeking to complete his father's ambition while simultaneously putting down several potential revolts that resulted in part from the death of Hasdrubal, which menaced the Carthaginian possessions already conquered thus far. He attacked the tribe known as the Olcades and captured their chief town of Althaea.[20] Neighbouring tribes were surprised at the vigour and rapacity of this attack,[20] as a result of which they submitted to the Carthaginians.[3] He received tribute from all of these recently subjugated tribes, and marched his army back to Cartagena, where he rewarded his troops with gifts and promised more gifts in the future.[20] During the next two years, Hannibal reduced all of Iberia south of the Ebro to subjection, excepting the city of Saguntum, which, under the aegis of Rome, was outside of his immediate plans. Catalonia and Saguntum were now the only areas of the peninsula not in Hannibal's possession.[24]

Roman foreign relations

Hannibal was well-informed on Roman politics, and realized that this was an opportune time to attack. He had Gallic spies in every corner of the Roman Republic, even within the inner circles of the Senate itself.[25] The Romans had spent the years since the end of the First Punic War (264–241 BC)[26] tightening their grip on the Italian peninsula by taking important geographical positions in the peninsula in addition to extending Rome's grip on Sicily, Corsica and Sardinia.

In addition to this, the Romans had been at war with the Padane Gauls off and on for more than a century.[27] The Boii had waged war upon the Romans in 238 BC, a war that lasted until 236 BC.[28] In 225 BC, the natives of northern Italy, seeing that Rome was again moving aggressively to colonize their territory, progressed to the attack,[29] but were defeated.[30] The Romans were determined to drive their borders right up to the Alps.[31] In 224 BC, the Boii submitted to Roman hegemony, and the next year the Anari also submitted to the Romans.[31][32]

In 223 BC,[31] the Romans engaged in another battle with the Gauls, this time the Insubres.[33] The Romans at first sustained significant losses against the Insubres while they were attempting to cross a ford near the junction of the Po and the Adda.[31] After encamping in this country for some days without taking any decisive action, the Roman consul on the spot decided to negotiate a settlement with the Insubres.[31] Under the terms of this freshly negotiated truce, the Romans marched out with full honours into the territory of their allies, the Cenomani.[31] However, once they were safe within the territory of the Cenomani, the Romans again marched their army into the territory of the Insubres and were victorious.[31][34]

In 222 BC, the Celts sent an embassy to the Roman Senate, pleading for peace. Seeing an opportunity for a triumph for themselves, the consuls Marcus Claudius and Gnaeus Cornelius vigorously rejected the embassy, and the Gauls prepared for war with the Romans. They hired 30,000 mercenaries from beyond the Alps and awaited the arrival of the Romans.[35] When the campaigning season began, the consular legions were marched into the Insubres territory again. A vigorous combat took place near Mediolanum, which resulted in the leaders of the Gallic revolt turning themselves over to the Romans.[35] With this victory, the Padane Gauls were unhappily subdued, and ripe for revolt.

Preparations

Hannibal, aware of the situation, sent a number of embassies to the Gallic tribes in the Po valley. In 220 BC, he had begun to communicate intimately with the Padane Gauls, so called because the Po in this era was called the "Padus" by the Romans, and these embassies brought with them offers of money, food and guides to the Carthaginians.[36]

This mission had the specific aim of establishing a safe place for Hannibal to debouch from the Alps into the Po valley. Hannibal did not know a great deal about the Alps, but he knew enough to know that it was going to be a difficult march. He had some scouts give him reports concerning this mountain chain, and he received reports of the difficulties to be encountered there from the Gauls themselves.[36] He did not desire to cross this rugged mountain chain and to descend into the Po valley with exhausted troops only to have to fight a battle.

Hannibal knew enough about the Alps to know in particular that the descent was steeper than the ascent into the Alps. This was one of the reasons he wanted to have allies into whose territory he could march.[a]

The Romans had poorly treated those Gauls whom they had recently conquered, distributing their land to Roman colonists and taking other unscrupulous measures to ensure their own security, against the freshly-conquered tribes. The Insubres, whose tribal territory immediately abutted the Alps, and the Boii, farther down the Po, were particularly pleased with Hannibal's proposed invasion. In addition, much of the Iberian peninsula was populated by related Gallic tribes,[37] and those same Gauls were serving in Hannibal's army. It would be easy indeed to establish intimate relations with these disaffected tribes, especially once he had debouched from the Alps and was amongst them and the Insubres and Boii and other tribes could see and speak with this army for themselves. Polybius had this to say about Hannibal's plans:

Conducted his enterprise with consummate judgement; for he had accurately ascertained the excellent nature of the country in which he was to arrive, and the hostile disposition of its inhabitants towards the Romans; and he had for guides and conductors through the difficult passes which lay in the way of natives of the country, men who were to partake of the same hopes with himself[38]

Siege of Saguntum

These preparations being completed, Hannibal sought to induce the Saguntines to come to arms with him and thereby declare war on Rome through her proxy. He did not desire to break the peace himself,[39][40] and resorted to a variety of stratagems in order to induce the Saguntines to attack.[39] However, the Saguntines did nothing except send a diplomatic mission to the Romans to complain about the belligerence of the Carthaginians.[39][41] The Senate sent a committee to Iberia[41] to attempt to settle the issue diplomatically.[39]

Hannibal openly scorned the Roman offer in the hopes that it would drive the commission to declare war. The commission was not fooled and knew that war was in the air.[39] The commission kept its peace, but brought news to Rome that Hannibal was prepared and was going to strike soon.[39][41] The Senate took a number of measures in order to free up its hands for the coming conflict with the Carthaginian. An Illyrian revolt was put down with energy, and the Romans sped up the construction of a number of fortresses in Cisalpine Gaul.[39] Demetrius of Pharos had abandoned his previous alliance with Rome and was now attacking Illyrian cities that had been incorporated into the Roman State.[42]

Hannibal could not achieve the ends that he had hoped for, and in the end he sent news to Carthage, where the peace party, his political enemies, were in power,[43] to the effect that the Saguntines were aggressively handling one of their subject tribes, the Torboletes,[39] and encamped in front of Saguntum to besiege it without awaiting any reply from Carthage. Words were exchanged in the Carthaginian Senate to the effect that Hannibal should be handed over to the Romans and his actions disavowed. However, the multitude in Carthage was too much in support of the conflict to order a stop to the war.[39]

The siege took place over the course of eight months,[39] and it is notable that the Romans did not send any aid to the Saguntines in spite of this being a part of the terms of their alliance. The Romans allowed themselves to be tied up in a war against the Illyrians,[39] and did not treat the Carthaginian threat from Iberia with the attention that it deserved.

After the siege, Hannibal sold all the inhabitants as slaves, and distributed the proceeds from those sales to his soldiers. In addition, all the booty from the sacking of the city was taken back to Carthage and distributed to the populace, in order to rally their support to his cause. The rest of the city's treasures were put into his war chest for his planned expedition.[44]

March through the Pyrenees

Hannibal had spent the winter after the siege of Saguntum in Cartagena (now in Spain), during which time he dismissed his troops to their own localities. He did this with the hope of cultivating the best possible morale in his army for the upcoming campaign, which he knew was going to be difficult. He left his brother Hasdrubal in charge of the administration of Carthaginian Iberia, as well as its defence against the Romans. In addition to this, he swapped the native troops of Iberia to Africa, and the native troops of Africa to Iberia.[45] This was done in order to minimize desertion and assure the loyalty of the troops while he was himself busy with the destruction of Rome. He also left his brother a number of ships.[46]

Hannibal foresaw problems if he left Catalonia as a bridgehead for the Romans. They had a number of allies in this country, and he could not allow the Romans a place to land in his base unopposed. As he was relying upon contingents of forces coming to him in Italy via the land route on which he was about to head out, he had to take and conquer this country. He had no intention of leaving Iberia to its fate once he was in Italy. Hannibal opted to take the region in a swift campaign, and to that effect he divided his army into three columns, in order to subdue the entirety of the region at the same time.

After receiving route information from his scouts and messages from the Celtic tribes that resided around the Alps, Hannibal set out with 90,000 heavy infantry from various African and Iberian nations, and 12,000 cavalry. From the Ebro to the Pyrenees, the Carthaginians confronted four tribes: the Illergetes, the Bargusii, the Aeronosii, and the Andosini. There were a number of cities here that Hannibal took, which Polybius does not specify. This campaign was conducted with speed in order to take as little time as possible in the reduction of this region. Polybius reports severe losses on Hannibal's part. Having reduced this area, he left his general Hanno in command of it, specifically over the Bargusii, whom he had reason to distrust due to their affiliation with the Romans. He left his brother in control of this country with 10,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry.[47]

At this early juncture in the campaign, he opted to send home another 10,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry. This was done to serve two purposes: he wanted to leave a force of men behind who would retain positive sentiments towards Hannibal himself; and he wanted the rest of the Iberians (in his army, as well as out) to believe that the chances of success in the expedition were good, as a result of which they would be more inclined to join the contingents of reinforcements that he anticipated calling up during the course of his expedition.[47] The remaining force consisted of 50,000 infantry and 9,000 cavalry.[48]

The principal column was the right column, and with it was the treasure chest, the cavalry, the baggage, all the other necessities of war, and Hannibal himself.[49] This was the critical column, and it was no coincidence that Hannibal was with it. As long as Hannibal had no ships to keep himself abreast of the exact movements of the Romans, he wanted to be present in person in case the Romans should make a landing in an attempt to attack his army on its ascent or descent through the Pyrenees. This column crossed the Ebro at the town of Edeba[50] and proceeded directly along the coast through Tarraco, Barcino, Gerunda, Emporiae and Illiberis.[49] Each of those oppida was taken and garrisoned in turn.

The second, or central, column crossed the Ebro at the oppidum of Mora and from there information is fairly sparse.[50] It proceeded through a number of valleys in this country, and had orders to subdue any tribes that resisted its advance. It eventually rejoined the principal column when it had completed its task.

The third, or left, column crossed the Ebro where it touches with the Sicoris River and proceeded along the river valley and into the mountain countries. It performed the same task as the second and the first columns did. When planning each of these marches, Hannibal ensured that the Rubrucatus river was athwart each of the columns' paths, so if any of the columns should be placed in a disadvantageous situation the other columns could march up and down the river in their support.[49]

The campaign was conducted over the course of two months, and was incredibly costly. Over the course of the two-month campaign, Hannibal lost 13,000 men.

March to the Rhône

The march to the Rhône after the descent through the Pyrenees was mostly uneventful for the Carthaginians, who had spent the previous July and August subduing aggressive tribes living in the Pyrenees.[51] The countries they travelled though had differing views of the Carthaginians, the Romans, and the passage of Hannibal's army through their land. Some tribes were friendly to Hannibal's cause, while others opposed him.[52]

Massalia (modern Marseille), a successful Greek trade emporium, had been under the influence of the Romans who had settled colonists there. Massalia feared the arriving Carthaginian army, and sought to influence the native tribes on the eastern bank of the Rhône to take up the cause of the Romans.[53]

Publius Scipio,[14][53] one of the consuls for 218 BC, received orders from the Senate to confront Hannibal in the theatre of the Ebro or the Pyrenees.[53][54][55] The Senate delegated to him 60 ships for this purpose, however he did not move quickly.[56] When he arrived in the Po area, there was an uprising amongst the freshly conquered Gauls.[53][57] More colonies were being established in the Po region, causing the Boii and Insubres to rebel when they became aware that Hannibal was heading to them.[54] Instead of employing the legions that were on hand for their intended Iberian expedition, the Senate ordered they should be sent to the Po under the command of a Praetor and new legions should be levied by the consul.[56][57] The formation of a new army was fairly easy for the Romans. There were so many citizens who were qualified for service in the army, that the government only had to inform the citizenry that more soldiers were needed and they would be required to serve. Many Romans, being required to serve at some point, spent portions of their youth training to serve in the legions.[citation needed]

Having organised new legions together – more slowly than the urgency of the situation demanded according to historians– he[who?] set sail from Ostia. There were no compasses at this time, and it was the habit of navigators to sail their ships along the coast and to stop at night for victuals.[58] After sailing north along the coast of the Italian peninsula, then turning west towards the Iberian peninsula, the consul ordered the fleet to stop in Massalia.[56][59] The time from Ostia to Massalia was five days.[56] When he arrived there, to his surprise he learned from the Massaliots that instead of Hannibal still being in Catalonia, as he had anticipated,[59] Hannibal was about four days march[60] north of their city on the far side of the Rhône.

Crossing the Rhône

Many of Hannibal's marches are shrouded in debate, especially the path he took over the Alps. However, modern historians agree on where Hannibal encamped his army on the western bank of the Rhône and see the river crossing as clearly conceived and crisply executed.[citation needed]

While Rome was idle and leaving allies in Catalonia to their fate at the hands of the Carthaginians, the Massaliots, allies of the Romans, were busy rousing the tribes on the eastern bank of the Rhône against the Carthaginians.[53] Upon the arrival of intelligence indicating the presence of the Carthaginians in the neighbourhood of Massalia, the consul gave up his proposed Iberian expedition and instead redirected his efforts to prevent Hannibal's crossing of the Rhône.[59] To this effect he sent a column of 300 horses [60] up the left (east) bank of the Rhône with orders to ascertain the exact location of Hannibal's army.[59] Hannibal received similar news to the effect that the Romans had just arrived with one of their consular armies (22,000 feet and 2,000 horses).[61]

Hannibal took advantage of the pre-existing hatred the Celts on the western bank had for the Romans and persuaded them to aid him in his crossing of this formidable obstacle.[59][60] He secured a number of their boats that were capable of making trips at sea and a collection of canoes.[59] In addition to purchasing these,[59] Hannibal was able to acquire their aid in building still other boats.[56][62] This process of preparing to cross the Rhone took two days.[62]

Awaiting the Carthaginian army on the eastern bank of the Rhône was a tribe of Gauls called the Cavares.[62][dubious – discuss] This tribe had fortified a camp on the far side of the river,[63] and was awaiting Hannibal's army to cross,[60] so as to attack them as they crossed.[63] There can be no doubt that Hannibal knew of Alexander the Great's crossing of the Hydaspes river in India as, from a tactical and strategic standpoint, he employed almost the same strategy. Hannibal formulated his plan according to this model (it is still held up as the standard way to cross rivers, even to modern cadets at military institutions[citation needed]) and ordered one of his lieutenants, Hanno, son of Bomilcar, to make a northern circuit to cross the Rhône at a location that he deemed to be suitable for the purpose.[60][63] The lieutenant was then ordered to march south and to take the Barbarian army in flank while he was crossing the river.[63]

The day and the night after all of the boats had been built and gathered,[63] Hanno was ordered up the bank and guided by native Gauls.[60][63] Approximately 40 kilometres (25 miles)[60][63] upriver at Pont St. Esprit there was an island that divided the Rhône into two small streams.[63][60] It was here that Hanno decided to cross, and ordered that boats and rafts should be constructed from materials that were at hand.[64][65] The Carthaginian detachment chopped down trees, lashing the logs together with reliable ropes they had brought with them from the army's stores.[63][64] By this means, Hanno's corps crossed the river and immediately proceeded south to the barbarian location.

During this time, Hannibal had been completing his preparations to cross the Rhône.[65] At this, the Carthaginian preparations had been particularly obvious and loud – Hannibal had ordered the preparations to be made without concern for secrecy,[65][63] knowing full well that Hanno's corps was marching down the eastern bank of the Rhône to attack the Cavares. His preparations were designed to draw their attention away from their northern flank and focus their attention on his own preparations.[65] Three days after setting out, Hanno arrived behind a tributary of the Rhone and gave the previously agreed upon signal to let Hannibal know that his force had arrived.[63][65] Hannibal immediately ordered the boats to cross.[63][64] The small corps was observing the principal army closely,[63] and on seeing it start its crossing, prepared to descend on the Cavares while the army was crossing.

The crossing itself was carefully designed to be as smooth as possible, details were thought out. The heavy horsemen were put across furthest upstream, and in the largest boats, so that the boats that Hannibal had less confidence in could be rowed to the western bank, in the lee of the larger and more sturdy craft.[64][65] As for the horses themselves, most of them were swum across the river at the side and stern of each boat.[64][65][63] However, some were put on boats fully saddled and ready for immediate use,[64] so that, once they debouched from the river, they could cover the infantry and the rest of the army while it formed up to attack the barbarians.[65]

Seeing that the Carthaginians were finally crossing, the Cavares rose from their entrenchments and prepared their army on the shore near the Carthaginian landing point.[64][66] The troops started to shout and jeer at each other while the Carthaginian army was in the midst of crossing.[67] These sorts of exchanges consisted primarily of encouraging their own men and challenging the other army to battle. Often during this period, to intimidate their enemy, troops would be ordered to pound their shields with their weapons and raise loud cries at precisely the same moment to create the greatest amount of noise.[citation needed]

It was at this time, while the Carthaginian army was in the middle of the stream jeering at the enemy from the boats and the Cavares were challenging them to come on from the western bank,[64] that Hanno's corps revealed themselves and charged down on the rear and flanks of the Cavares.[67][68] A small detachment of Hanno's force was assigned to set the Cavares' camp on fire,[67][68] but the majority of this force reeled in on the Cavares.[68] Some of the Cavares rushed to the defence of their camp,[67][68][69] but the majority remained at the location where they had been awaiting the arrival of what they had thought was all of Hannibal's army.[67][69] They were divided; and Hannibal, who was on one of the first boats, landed his men on the western bank of the Rhône amidst the confused Cavares and led the army against them. There was little resistance;[67] surrounded as the Cavares were, pandemonium took control of their ranks, and they retreated pell-mell away from the arrayed Carthaginian phalanx.

While the actual conflict took a short time, Hannibal had spent five days preparing this risky operation, ensuring that it was ready and as little as possible was left to chance.[69]

From the Rhône to the Alps

Hannibal needed to reach the Alps quickly in order to beat the onset of winter. He knew that if he waited until springtime on the far side of the mountains, the Romans would have time to raise another army. He had intelligence that the consular army was camped at the mouth of the Rhône. He sent 500 Numidian cavalry down the eastern bank of the river to acquire better information concerning the forces massed to oppose him. This force encountered 300 mounted Romans who had been sent up the river for the same purpose. The Numidians were defeated with 240 of their number killed in this exchange between scouting parties, in addition to 140 Roman losses. The Numidians were followed back to the Carthaginian camp, which was almost assembled excepting the elephants, which required more time getting across. Upon seeing Hannibal had not crossed with the whole of his force, the scouts raced back to the coast to alert the consul. Upon receiving this information, the consul dispatched his army up the river in boats, but arrived too late.[66]

In the face of winter and hostile tribes, the consul decided to return to Italy and await the arrival of Hannibal as he descended from the Alps. However, in accordance with the Senate's orders, the consul ordered his brother, Gnaeus Scipio, to take a majority of the army to Spain.[66] The consul proposed attacking Hannibal's overextended and vulnerable lines of communications and supply. Despite their established tactical system (formations and troop evolutions, etc.), the Romans were used to fighting by marching their troops to their enemies' army, forming their army up and attacking. They did not know how to force an enemy to battle by cutting off their communications, and they were not aware of which flank was the strategic flank of an enemy in a battle. In addition, they were negligent about their order of march,[70] and early Roman history records many massacres of consular armies by other nations because of their lack of proper precaution against these.[71]

On getting the whole of his army on the left bank of the Rhone, Hannibal introduced his army to Magilus[66] and other Gallic chiefs of the Po valley.[66][72] Hannibal's purpose was to inspire his men with confidence in the planned expedition by showing them Padane Gallic chieftains who offered them their aid. Speaking through an interpreter,[72] Magilus spoke of the support that the recently conquered Padane Gauls had for the Carthaginians and their mission of destroying Rome. Hannibal then addressed the officers himself. The troops' enthusiasm was said to have been uplifted by Hannibal's address.[66]

Upon crossing the river, Hannibal ordered his infantry to start their march the day after the assembly, followed by the supply train.[73] Not knowing that the Romans were ultimately going to set out for Italy, when his cavalry had crossed the river he ordered them to curtain his march on his southern flank, towards the sea.[66] His cavalry would have formed a screen which would have been employed to protect him from the Romans were they to advance upon him from that direction. The cavalry would skirmish with the Roman scouts, while giving the rest of the army time to form up. This contingency did not occur. Hannibal was in the rearguard with the elephants.[73] This was the direction that he assumed that the Romans would be most likely to advance from (that is from the west) as he had some idea that they were behind him. The rearguard was well manned to ensure that it could skirmish with the Roman army, while the main body of his infantry and cavalry could form up for battle against the Romans if they should attack from that quarter. This contingency, however, also did not occur.

While assuming this order of march, Hannibal marched towards the Insula.[73] He had ordered his infantry to get a head start, and it marched to the Isère in six days, marching 20 kilometres (12+1⁄2 miles) per day. The cavalry and rear guard only took four days, a march of 30 km (19 mi) per day. In this period, the body as a whole had marched 120 km (75 mi).[74]

When Hannibal's army made contact with the Insula, he arrived in a Gallic chiefdom that was in the midst of a civil conflict.[75] Hannibal chose the cause of the elder of the two combatants, Brancus.[74] After deciding against the cause of the younger and less popularly supported one,[74] he formed an alliance with Brancus. From this tribe he received supplies that were required for the expedition across the Alps. In addition, he received Brancus' diplomatic protection. Up until the Alps proper, he did not have to fend off any tribes.

Ascent of the Alps

Hannibal's actual route through the Alps is uncertain and the valleys and passes he crossed are contested by historians. The events recorded in ancient accounts, and their relationship to the Alpine geography, has been a matter of historiographical dispute since the decades following the Second Punic War.[citation needed] Identification of the pass – the highest point of Hannibal's route – and the beginning of his descent, which Hannibal took through the Alpine range, determines which route his army followed.

Proposals have been made for the following passes:[76][77][78][79][80]

- Little St Bernard Pass

- Col de Clapier

- Col de la Traversette

- Col de Montgenèvre

- The pass near Mont Cenis

Theodore Ayrault Dodge, writing in the late nineteenth century, argued that Hannibal used the Little St Bernard Pass, but modern historian John Francis Lazenby concluded that Col de Clapier was the pass used by Hannibal.[81] More recently, W. C. Mahaney has argued Col de la Traversette closest fits the records of ancient authors.[82] Biostratigraphic archaeological data has reinforced the case for Col de la Traversette; analysis of peat bogs near watercourses on both sides of the pass's summit showed that the ground was heavily disturbed "by thousands, perhaps tens of thousands, of animals and humans" and that the soil bore traces of unique levels of Clostridia bacteria associated with the digestive tract of horses and mules.[83] Radiocarbon dating secured dates of 2168 BP or c.218 BC, the year of Hannibal's march. Mahaney et al. have concluded that this and other evidence strongly supports the Col de la Traversette as being the 'Hannibalic Route' as had been argued by Gavin de Beer in 1974. De Beer was one of only three interpreters – the others being John Lazenby and Jakob Seibert de. – to have visited all the Alpine high passes and presented a view on which was most plausible. Both De Beer and Seibert had selected the Col de la Traversette as the one most closely matching the ancient descriptions.[84]

Polybius wrote that Hannibal had crossed the highest of the Alpine passes. Col de la Traversette, between the upper Guil valley and the upper Po river, is the highest pass. It is moreover the most southerly, as Varro in his De re rustica relates, agreeing that Hannibal's Pass was the highest in the Western Alps and the most southerly. Mahaney et al. argue that factors used by De Beer to support Col de la Traversette including "gauging ancient place names against modern, close scrutiny of times of flood in major rivers and distant viewing of the Po plains" taken together with "massive radiocarbon and microbiological and parasitical evidence" from the alluvial sediments on either side of the pass furnish "supporting evidence, proof if you will" that Hannibal's invasion went that way.[85]

According to Dodge, Hannibal marched in the direction of Mt. Du Chat towards the village of Aquste[86] and from there to Chevelu,[87] to the pass by Mt. Du Chat. There he found that the passes had been fortified by the Allobroges. He sent out spies to ascertain if there was any weakness in their disposition. These spies found that the barbarians only maintained their position at the camp during the day, and left their fortified position at night. In order to make the Allobroges believe that he did not deem a night assault prudent, he ordered that as many camp-fires be lit as possible, in order to induce them into believing that he was settling down before their encampment along the mountains. However, once they left their fortifications, he led his best troops up to their fortifications and seized control of the pass.[88]

Hiding his men in the mountain brush on a cliff that arose immediately above and to the right off Hannibal's route of march, about 100 feet or so above the path, Hannibal stationed his slingers and archers there. This overhang was an excellent place from which to attack an enemy while it was marching in column through the pass.[89] The descent from this pass was steep, and the Carthaginians were having a hard time marching down this side of the pass,[89] especially the baggage animals.[88] The Barbarians, seeing this, attacked anyway, in spite of their disadvantageous position. More baggage animals were lost in the confusion of the Barbarian attack, and they rolled off of the precipices to their deaths.[89] This put Hannibal in a difficult situation. However, Hannibal, at the head of the same elite corps that he led to take the overhang, led them against these determined barbarians. Virtually all of these barbarians died in the ensuing combat, as they were fighting with their backs to a steep precipice, trying to throw their arrows and darts uphill at the advancing Carthaginians.[88] After this contest of arms, the baggage was held together in good order and the Carthaginian army followed the road down to the plain that begins roughly at modern Bourget.[90]

Dodge states that this plain was 4–6 miles wide in most places, and was almost entirely stripped of defenders since they were all stationed at the Mt. Du Chat pass. Hannibal marched his army to modern Chambery and took their city easily, stripping it of all its horses, captives, beasts of burden and grain. In addition, there were enough supplies for three days' rations for the army. This must have been welcome considering that no small portion of their supplies had been lost when the pack animals had fallen over the precipice in the course of the previous action. He then ordered this town to be destroyed, in order to demonstrate to the Barbarians of this country what would happen if they opposed him in the same fashion as this tribe had.[90]

He encamped there to give his men time to rest after their exhausting work, and to collect further rations. Hannibal then addressed his army, and we are informed that they were made to appreciate the extent of the effort they were about to undergo and were raised to good spirits in spite of the difficult nature of their undertaking.[91]

The Carthaginians continued their march and at modern Albertville they encountered the Centrones, who brought gifts and cattle for the troops. In addition, they brought hostages in order to convince Hannibal of their commitment to his cause.[91] Hannibal was concerned and suspicious of the Centrones, though he hid this from them,[91] and the Centrones guided his army for two days.[92] According to Dodge, they marched through the Little St Bernard Pass near the village of Séez, and as they did, the pass narrowed and the Centrones turned against the Carthaginians. Some military critics, notably Napoleon,[93] challenge that this was actually the place where the ambush took place, but the valley through which the Carthaginians were marching was the only one that could sustain a population that was capable of attacking the Carthaginian army and simultaneously sustaining the Carthaginians on their march.[93]

The Centrones waited to attack, first allowing half of the army to move through the pass.[94] This was meant to divide Hannibal's troops and supplies and make it difficult for his army to organize a counter-attack, but Hannibal, having anticipated deceit by the Centrones, had arranged his army with elephants, cavalry and baggage in front, while his hoplites followed in the rear. Centrones forces had positioned themselves on the slopes parallel to Hannibal's army and used this higher ground to roll boulders and rain rocks down at the Carthaginian army, killing many more pack animals. Confusion reigned in the ranks caught in the pass. However, Hannibal's heavily armed rearguard held back from entering the pass,[94] forcing the Barbarians to descend to fight. The rearguard was thus able to hold off the attackers, before Hannibal and the half of his army not separated from him were forced to spend the night near a large white rock, which Polybius writes "afforded them protection"[95] and is described by William Brockedon, who investigated Hannibal's route through the Alps, as being a "vast mass of gypsum...as a military position, its occupation secures the defence of the pass."[96] By morning, the Centrones were no longer in the area.

The army rested here for two days. It was the end of October and snowy weather, the length of the campaign, ferocity of the fighting, and the loss of animals sapped morale in the army's ranks.[97] From their outset in Iberia, Hannibal's troops had been marching for over five months and the army had greatly reduced in size. The majority of Hannibal's fighters were unaccustomed to the extreme cold of the high Alps, being mostly from Africa and Iberia.[98] According to Polybius,[99] Hannibal assembled his men, declared to them that the end of their campaign was drawing near; and pointed to the view of Italy, showing his soldiers the Po Valley and the plains near it, and reminded them they had been assured of Gallic friendship and aid.[97] The Po Valley is not visible from Little St Bernard Pass[100] and if Hannibal took that path, it is likely that he pointed in the direction of the Po Valley but it was not in sight. If, however, Hannibal had ascended the Col de la Traversette, the Po Valley would indeed have been visible from the pass's summit, vindicating Polybius's account.[101] After three days of rest, Hannibal ordered the descent from the Alps to begin.[102]

Descent to Italy

The snow on the southern side of the Alps melts and thaws to a greater or lesser extent during the course of the day, and then refreezes at night.[98] In addition, the Italian side of the Alps is much steeper.[98] Many men lost their footing down this side of the Alps and died.

At an early point in their descent, the army came upon a section of the path that had been blocked by a landslide. This section of the path was broken for about 300 yards.[103] Hannibal attempted to detour by marching through a place where there was a great deal of snow – the Alps' altitude at this point retains snowpack year around. They made some headway, at the cost of no small portion of the pack animals that were left, before Hannibal came to appreciate that this route was impossible for an army to traverse. Hannibal marched his men back to the point in their path prior to their detour, near the broken stretch of the path and set up camp.[104]

From here, Hannibal ordered his men to set about fixing the mule path. Working in relays, the army set about this labour-intensive task under the eyes of Hannibal, who was constantly encouraging them. Both the sick and the healthy were put to this task. The next day the road was in sufficient condition to permit the cavalry and pack animals to cross the broken stretch of road.[104] Hannibal ordered that these should instantly race down below the foliage line (2 miles below the summit of the Alps)[105] and should be allowed access to the pastures there.[104]

However, Hannibal's remaining elephants, which were completely famished, were still unable to proceed along the path. Hannibal's Numidian cavalry carried on working on the road, taking three more days to fix it sufficiently to allow the elephants to cross.[104] Getting the animals across this stretch of road, Hannibal raced ahead of the rearguard to the part of the army that was below the pasture line.[106] It took the army three days to march from this place into "the plains which are near the Po" according to Polybius. Hannibal then focused on, according to Polybius, "[the] best means of reviving the spirits of his troops and restoring the men and horses to their former vigour and condition."[105] Hannibal ordered his men to encamp at a point which is near modern Ivrea.[107] This effectively marked the end of their crossing of the Alps, but the beginning of their campaign in Italy and their role in some of the decisive battles of the Second Punic War.

In culture

In part III of Jonathan Swift's 1726 prose satire, Gulliver's Travels, the eponymous protagonist, Gulliver, visits "Glubbdubdrib", a fictional island populated by sorcerers. Invited by the governor of the island who is capable of summoning the dead, Gulliver summons Hannibal and learns that he did not actually utilize fire and vinegar to melt boulders obstructing his path, and that it was probably a conjured up myth.[108]

Artist Jacques-Louis David's 1800 painting (and later copies) of Napoleon crossing St. Bernard Pass references Hannibal's crossing of the Alps by inscribing his name on the rock beneath Napoleon's rearing horse.[109][110] Kehinde Wiley's 2005 Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps, a reinterpretation of David's image, includes Hannibal's name and adds "WILLIAMS", the last name of the model who posed for the painting. [111]

See also

Notes

- ^ The Alps rose as a result of the pressure of the African plate as it moved north against the stable Eurasian landmass; the northward direction of this movement made the Italian side of the Alps considerably steeper.

References

- ^ Lancel, Serge, Hannibal, p. 71

- ^ a b Yardley, J.C.; Hoyos, D. (2009). Hannibal's War: Books 21-30. OUP Oxford. pp. 620, 629. ISBN 978-0-19-955597-0.

Hannibal crossed the Alps by one of the western passes, arriving in the territory of the Insubres according to Polybius (3.56), but the Taurini according to both Livy (21.38) and, it seems, Polybius himself later on (see below). Polybius does not identify the pass; Livy (ibid.) discusses the question briefly but only to dismiss the Poenine pass, or Great St Bernard, and the Cremo, or Little St Bernard. His arguments are sensible, but he does not then say which pass, if any, he himself thinks was the right one. The Alps had not been mapped or even extensively visited by Greeks and Romans before 218. So we cannot say how precise were the accounts of the primary sources (on whom see Introduction). Our main authorities are Polybius and Livy. Polybius reports that he himself visited the area and questioned eyewitnesses (3.48); but such persons must have been very old by then, and relying chiefly or wholly on their memories. He must also be using some or all of the primary sources. Livy evidently combines Polybius' account with at least one other; or, less likely, reproduces a predecessor who did the combining. Both mention relatively few place names after Hannibal's crossing of the Rhône, and not all are readily identifiable. With no archaeological evidence available, every theory thus depends on interpreting these accounts and comparing them with existing topography. Unsurprisingly, theories abound (see Further Reading below) and none has won universal acceptance.... Polybius' distance-reckonings look like broad estimates, when not guesstimates... We may note how important Livy's non-Polybian contribution is. From the Rhône-crossing to the descent into Italy, Polybius supplies three names: Island, Skaras, and Allobroges. It is Livy's range of tribe- and place names, despite the faults, that makes practicable any attempt to reconstruct Hannibal's route over the Alps.

- ^ a b Walbank 1979, p. 187

- ^ Delbrück, Hans Jr.; translated from the German by Walter J. Renfroe (1990). History of the art of war. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press/ Bison Book. ISBN 978-0-8032-9199-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dodge 1994, p. 131

- ^ Henty, G. A. (2017). The Young Carthaginian – A Story of The Times of Hannibal: Big Adventurer. VM eBooks.

- ^ Dodge, Theodore (1994). Hannibal. Mechanicsburg, PA: Greenhill Books.

- ^ Walbank 1979, p. 189

- ^ a b Delbrück 1990, p. 303

- ^ a b Delbrück 1990, p. 312

- ^ a b c d e Dodge 1994, p. 146

- ^ a b c d e f Paton 1922, p. 243

- ^ Walbank, Polybius; transl. by Ian Scott-Kilvert; selected with an introduction by F.W. (1981). The rise of the Roman Empire (Reprint ed.). Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-044362-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Walbank 1979, p. 111

- ^ Winlow, C.V. "Our Little Carthaginian Cousin of Long Ago: With Hannibal". Heritage History.

- ^ a b c Mommsen 1862, p. 94

- ^ a b c Dodge 1994, p. 147

- ^ a b Paton 1922, p. 273

- ^ Mommsen 1862, p. 92

- ^ a b c d e f Walbank 1979, p. 190

- ^ Dodge 1994, p. 148

- ^ a b Paton 1922, p. 331

- ^ Lancel, Serge (1998). Hannibal. Blackwell. p. 43. ISBN 9780631206316.

- ^ Dodge 1994, p. 157

- ^ Mommsen 1862, p. 95

- ^ Mommsen 1862, p. 62

- ^ Paton 1922, p. 287

- ^ Mommsen 1862, p. 77

- ^ Mommsen 1862, p. 78

- ^ Paton 1922, p. 317

- ^ a b c d e f g Paton 1922, p. 319

- ^ Mommsen 1862, p. 81

- ^ Mommsen 1862, p. 82

- ^ Paton 1922, p. 321

- ^ a b Paton 1922, p. 325

- ^ a b Dodge 1994, p. 164

- ^ Dodge 1994, p. 165

- ^ Dodge 1994, p. 166–167

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Mommsen 1862, p. 96

- ^ Walbank 1979, p. 191

- ^ a b c Walbank 1979, p. 192

- ^ Walbank 1979, p. 193

- ^ Mommsen 1862, p. 91

- ^ Walbank 1979, p. 194

- ^ Walbank 1979, p. 209

- ^ Walbank 1979, p. 210

- ^ a b Walbank 1979, p. 211

- ^ Walbank 1979, p. 212

- ^ a b c Dodge 1994, p. 173

- ^ a b Dodge 1994, p. 172

- ^ Dodge 1994, p. 171

- ^ Dodge 1994, p. 176

- ^ a b c d e Dodge 1994, p. 177

- ^ a b Walbank 1979, p. 213

- ^ Mommsen, Theodor (2009). The history of Rome (Digitally printed version ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-00974-4.

- ^ a b c d e Walbank 1979, p. 214

- ^ a b Mommsen 1862, p. 102

- ^ Dodge 1994, p. 127

- ^ a b c d e f g Dodge 1994, p. 178

- ^ a b c d e f g h Walbank 1979, p. 215

- ^ Mommsen 1862, p. 103

- ^ a b c Dodge 1994, p. 179

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Dodge 1994, p. 180

- ^ a b c d e f g h Walbank 1979, p. 216

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dodge 1994, p. 181

- ^ a b c d e f g Dodge 1994, p. 184

- ^ a b c d e f Dodge 1994, p. 182

- ^ a b c d Walbank 1979, p. 217

- ^ a b c Mommsen 1862, p. 104

- ^ Dodge 1994, p. 63

- ^ Dodge 1994, p. 64

- ^ a b Mommsen 1862, p. 105

- ^ a b c Dodge 1994, p. 187

- ^ a b c Dodge 1994, p. 199

- ^ Dodge 1994, p. 200

- ^ Philip Ball (3 April 2016). "The truth about Hannibal's route across the Alps". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ "Dung clue to Hannibal's Alpine crossing". BBC News. 5 April 2016.

- ^ "Researchers Find Hannibal's Route through Alps". The British Journal. 8 April 2016. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ^ Jia, Anny (16 May 2007). "In the Alps, hunting for Hannibal's trail". Stanford Report. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ^ Lidz, Franz. "How (and Where) Did Hannibal Cross the Alps?". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ Hannibal's War: A Military History of the Second Punic War, p. 46, John Francis Lazenby University of Oklahoma Press, 1998 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Mahaney, W. C., Allen, C. C. R., Pentlavalli, P., Dirszowsky, O., Tricart, P., Keiser, L., Somelar, P., Kelleher, B., Murphy, B., Costa, P. J. M., and Julig, P., 2014, "Polybius's 'previous landslide': proof that Hannibal's invasion route crossed the Col de la Traversette", Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, 14(2), 1–20.

- ^ Mahaney, W. C., Allen, C. C. R., Pentlavalli, P., Kulakova, A., Young, J. M., Dirszowsky, R. W., West, A., Kelleher, B., Jordan, S., Pulleyblank, C., O'Reilly, S., Murphy, B. T., Lasberg, K., Somelar, P., Garneau, M., Finkelstein, S. A., Sobol, M. K., Kalm, V., Costa, P. J. M., Hancock, R. G. V., Hart, K. M., Tricart, P., Barendregt, R. W., Bunch, T. E., and Milner, M. W., 2017, "Biostratigraphic evidence relating to the age‐old question of Hannibal's invasion of Italy", Archaeometry, vol. 59, 164–190. [1]

- ^ de Beer, S. G., 1974, Hannibal: The struggle for power in the Mediterranean, Book Club Associates, London.

- ^ W. C. Mahaney, P. Somelar, A. West, R. W. Dirszowsky, C. C. R. Allen, T. K. Remmel, P. Tricart "Reconnaissance of the Hannibalic Route in the Upper Po Valley, Italy: Correlation with Biostratigraphic Historical Archaeological Evidence in the Upper Guil Valley, France", Archaeometry, 2018. [2]

- ^ Dodge 1994, p. 202

- ^ Dodge 1994, p. 203

- ^ a b c Dodge 1994, p. 205

- ^ a b c Dodge 1994, p. 206

- ^ a b Dodge 1994, p. 208

- ^ a b c Dodge 1994, p. 210

- ^ "Polybius, Histories, book 3, Treachery of the Gauls".

- ^ a b Dodge 1994, p. 212

- ^ a b Dodge 1994, p. 216

- ^ "Polybius, Histories, book 3, the White Rock".

- ^ Brockedon, William (1877). Illustrations of the Passes of the Alps, by which Italy Communicates with France, Switzerland, and Germany. H. G. Bohn.

- ^ a b Dodge 1994, p. 222

- ^ a b c Dodge 1994, p. 223

- ^ Polybius, History III:54 ("Polybius, Histories, book 3, "The Descent into Italy"".)

- ^ Brockedon, William (1877). Illustrations of the Passes of the Alps, by which Italy Communicates with France, Switzerland, and Germany. H. G. Bohn.

- ^ de Beer, S. G., 1969, Hannibal: Challenging Rome's supremacy, Viking, New York. pp. 163–180 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Livy, Histories XXI:37; Polybius, History III:54

- ^ Dodge 1994, p. 224

- ^ a b c d Dodge 1994, p. 225

- ^ a b Dodge 1994, p. 228

- ^ Dodge 1994, p. 229

- ^ Dodge 1994, p. 230

- ^ "Chapter 7". www.cliffsnotes.com. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ "Le Premier consul franchissant les Alpes au col du Grand-Saint-Bernard". musees-nationaux-malmaison.fr (in French). Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ Facos, Michelle (22 February 2011). An Introduction to Nineteenth-Century Art. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-84070-8.

- ^ "Brooklyn Museum". www.brooklynmuseum.org. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

Further reading

- Dodge, Theodore Ayrault. 1994 Hannibal [ISBN missing]

- Hoyos, B. D. 2003. Hannibal's Dynasty: Power and Politics In the Western Mediterranean, 247–183 BC. London: Routledge. [ISBN missing]

- Hunt, Patrick. 2017. Hannibal. New York: Simon & Schuster. [ISBN missing]

- Kuhle, M., and Kuhle, S. 2015. "Lost in Translation or Can We Still Understand What Polybius Says about Hannibal's Crossing of the Alps? – A Reply to Mahaney (Archaeometry 55 (2013): 1196–1204)." Archaeometry 57: 759–771. doi:10.1111/arcm.12115

- Mahaney, W. C. 2016. "The Hannibal Route Controversy and Future Historical Archaeological Exploration in the Western Alps". Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry 16 (2): 97–105 doi:10.5281/zenodo.53065

Mahaney, W.C., 2008. 'Hannibal's Odyssey: the environmental background to the alpine invasion of Italia' Gorgias Press, Piscataway, NJ,221 pp. ISBN 978-1-59333-951-7.