Indigo bunting

| Indigo bunting | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male at Quintana, Texas, spring migration | |

| |

| Female | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Cardinalidae |

| Genus: | Passerina |

| Species: | P. cyanea

|

| Binomial name | |

| Passerina cyanea (Linnaeus, 1766)

| |

| |

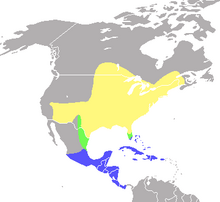

| Range of the indigo bunting

Summer-only range Migratory range Winter-only range

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The indigo bunting (Passerina cyanea) is a small seed-eating bird in the cardinal family, Cardinalidae. It is migratory, ranging from southern Canada to northern Florida during the breeding season, and from southern Florida to northern South America during the winter. It often migrates by night, using the stars to navigate. Its habitat is farmland, brush areas, and open woodland. The indigo bunting is closely related to the lazuli bunting and interbreeds with the species where their ranges overlap.

The indigo bunting is a small bird, measuring 11.5–13 cm (4.5–5.1 in) in length. It displays sexual dimorphism in its coloration; the male is vibrant blue in the summer, with brightly colored plumage during the breeding season to attract a mate. It is brown during the winter months, while the female is brown year-round. Nest-building and incubation are done solely by the female. The diet of the indigo bunting consists primarily of insects during the summer months and seeds during the winter months.

Taxonomy

[edit]

The indigo bunting is included in the family Cardinalidae, which is made up of passerine birds found in North and South America, and is one of seven birds in the genus Passerina.[2] It was originally described as Tanagra cyanea by Linnaeus in his 18th-century work, Systema Naturae. The current genus name, Passerina, is derived from the Latin term passer for true sparrows and similar small birds,[3] while the species name, cyanea, is Latin for cyan, the color of the male's breeding plumage.[4]

The indigo bunting is a close relative of the lazuli bunting and interbreeds with the species where their ranges overlap, in the Great Plains.[5] They were declared to form a superspecies by the American Ornithologists' Union in 1983.[6] However, according to sequencing of the mitochondrial cytochrome-b gene of members of the genus Passerina, it was determined that the indigo bunting and lazuli bunting are not, in fact, sister taxa. The indigo bunting is the sister of two sister groups, a "blue" (lazuli bunting and blue grosbeak) and a "painted" (rose-bellied bunting, orange-breasted bunting, varied bunting, and painted bunting) clade. This genetic study shows these species diverged between 4.1 and 7.3 million years ago. This timing, which is consistent with fossil evidence, coincides with a late-Miocene cooling, which caused the evolution of a variety of western grassland habitats. Evolving to reduce size may have allowed buntings to exploit grass seeds as a food source.[7]

Description

[edit]

The indigo bunting is a smallish songbird, around the size of a small sparrow. It measures 11.5–15 cm (4.5–5.9 in) long, with a wingspan of 18–23 cm (7.1–9.1 in).[8][9] Body mass averages 14.5 g (0.51 oz), with a reported range of 11.2–21.4 g (0.40–0.75 oz).[10] During the breeding season, the adult male appears mostly a vibrant cerulean blue. Only the head is indigo. The wings and tail are black with cerulean blue edges. In fall and winter plumage, the male has brown edges to the blue body and head feathers, which overlap to make the bird appear mostly brown. The adult female is brown on the upperparts and lighter brown on the underparts. It has indistinct wing bars and is faintly streaked with darker markings underneath.[11] The immature bird resembles the female in coloring, although a male may have hints of blue on the tail and shoulders and have darker streaks on the underside. The beak is short and conical. In the adult female, the beak is light brown tinged with blue, and in the adult male the upper half is brownish-black while the lower is light blue.[12] The feet and legs are black or gray.[13]

First years and adult males are distinguishable through close observations of the skull and its degree of ossification. Juvenile skulls have a slightly pinkish color that gives under pressure due to its singular layer. Adults instead have a double layer skull, which gives more resistance when applying pressure. First year birds also tend to have a fleshy, yellow gape in the corner of the mouth, apparent in all months except October and November. When comparing males to females that both have brown molt, increased wing length and weight typically indicate a bunting is a male.[14]

As indicated by data collected from Charles H. Blake from his banding experiments in Hillsborough, NC, the Indigo Bunting has a weighted annual survival rate of 0.585. Using his own methods (Blake 1967, p. 5) and a pool of 25 indigo buntings captured and observed, it was determined that approximately two out of twenty-five indigo buntings should live up to six years. Using the calculated annual rate of six-year-old birds obtained (2/25 = 0.08), an annual rate of 0.656 was calculated, 12% higher than the annual rate of 0.585, leading to the 1 out of 25 statistic. The oldest recorded bunting was at least 13 years and 3 months old.[15] However, not much emphasis should be placed on these values since the pool of individuals is small, where any individual can affect the weighted average.[16]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The habitat of the indigo bunting is brushy forest edges, open deciduous woods, second growth woodland, and farmland.[17] Increases in population size have been seen in the event of forest clearings and development of land into farms.[18] The breeding range stretches from southern Canada to Maine, south to northern Florida and eastern Texas, and westward to southern Nevada. The winter range begins in southern Florida and central Mexico and stretches south through the West Indies and Central America to northern South America.[9] It has occurred as a vagrant in Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Denmark, Ecuador, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Netherlands, the Netherlands Antilles, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, Serbia and the United Kingdom.[19]

Ecology and behavior

[edit]Vocalizations

[edit]The indigo bunting communicates through vocalizations and visual cues. A sharp chip! call is used by both sexes, and is used as an alarm call if a nest or chick is threatened. A high-pitched, buzzed zeeep is used as a contact call when the indigo bunting is in flight.[20] The song of the male bird is a high-pitched buzzed sweet-sweet chew-chew sweet-sweet, lasting two to four seconds, sung to mark his territory to other males and to attract females. Each male has a single complex song,[13] which he sings while perched on elevated objects, such as posts, wires, and bush-tops.[21] In areas where the ranges of the lazuli bunting and the indigo bunting overlap, the males defend territories from each another.[22]

Migration

[edit]Migration takes place in April and May and then again in September and October.[9] Previous research indicates that towards the end of August there is a spike in migration, indicated by a rapid surge of captures in the last ten days of August. Migration activities peak in late September and fall off rapidly as October approaches. Only a small percentage of buntings remain as summer residents instead of migrating (7.2% of banded birds in Burke's observation).[16]

The indigo bunting often migrates during the night, using the stars to navigate.[23] This is not an unusual proposal, for many other birds such as the blackcaps or red-backed shrikes were used to test if birds have orientated migratory behavior or Zugunruhe. Research indicates that indigo buntings placed in funnel cages outside on cloudless autumn nights or in artificial planetariums made more southern directional choices. When introduced to increasingly overcast nights, many bunting's abilities to distinctively make southern directional changes decreased, possibly indicating a negative correlation between Zugunruhe and cloud coverage. When in the artificial planetarium scenario and in the presence of a magnetic field similar to Earth's, birds were unable to orientate themselves in a no-star environment, indicating that past hypotheses supporting that birds use geophysical clues as well may be incorrect.[24]

Indigo buntings do not rely on individual stars or the general brightness of groups of stars, but instead use them as clues in navigation. Prior experiments removing certain constellations and stars (Big Dipper, Cassiopeia or Polaris) from the sky had minimal effect on Zugunruhe. Indigo buntings do use the northern sky to help navigate both in the fall and in the spring. It was thought that the bunting has an internal clock, being able to compensate for the movement of stars. However, temporal compensation for stellar motion is not a part of their migratory methods.[25]

In captivity, since it cannot migrate, it experiences disorientation in April and May and in September and October if it cannot see the stars from its enclosure.[9]

While debate has occurred over the years about how birds migrate near the Gulf of Mexico, indigo buntings migrate to South America by flying both over the Gulf of Mexico and around the Gulf of Mexico, with a majority of buntings choosing the trans-Gulf path. Past evidence indicated that indigo buntings did not have a high enough fat content to travel across the Gulf, but that evidence is misleading since most of those birds supporting that study were immature, not having a high body fat content.[18]

Since indigo buntings and many other birds are at their lightest after mating season, questions arose whether increases in overall weight were attributed to fat or other factors such as water weight, or carbohydrates. Research indicates that most if not all weight gain is a gain in fat content.[18]

Quantitative methods of estimating flight range instead look at metabolic rates of the bunting and how much fat it has to use as fuel. Research indicates that the metabolic rate of a lean 13 g (0.46 oz) indigo bunting is 0.64 kcal/hour. With an average speed of 20 mph, 5 extra grams of fat (47.5 kcal of energy) extends a bunting's range to six hundred and eighty-eight miles (1,107 km). 19 g (0.67 oz) is equivalent to eight hundred and twenty-six miles (1,329 km). Given that the trip across the Gulf of Mexico from Florida is approximately six hundred miles (966 km), buntings weighing at least 18 g could make the trip without any stops.[18]

Breeding

[edit]

These birds are generally monogamous but not always faithful to their partner. In the western part of their range, they often hybridize with the lazuli bunting. Nesting sites are located in dense shrub or a low tree, generally 0.3–1 m (0.98–3.28 ft) above the ground, but rarely up to 9 m (30 ft).[22] The nest itself is constructed of leaves, coarse grasses, stems, and strips of bark, lined with soft grass or deer hair and is bound with spider web. It is constructed by the female, who cares for the eggs alone.[22] The clutch consists of one to four eggs, but usually contains three to four. The eggs are white and usually unmarked, though some may be marked with brownish spots, averaging 18.7 mm × 13.7 mm (0.74 in × 0.54 in) in size.[26] The eggs are incubated for 12 to 13 days and the chicks are altricial at hatching.[9] Chicks fledge 10 to 12 days after hatching. Most pairs raise two broods per year, and the male may feed newly fledged young while the females incubate the next clutch of eggs.[27]

The brown-headed cowbird may parasitize this species.[8] Indigo buntings abandon their nest if a cowbird egg appears before they lay any of their own eggs, but accept the egg after that point. Pairs with parasitized nests have less reproductive success. The bunting chicks hatch, but have lower survival rates as they must compete with the cowbird chick for food.[28]

Diet

[edit]The indigo bunting forages for food on the ground or in trees or shrubs.[22] In winter, it often feeds in flocks with other indigo buntings, but is a solitary feeder during the breeding season.[13] During the breeding season, the species eats seeds of grasses and herbs, berries, spiders and insects, including caterpillars, grasshoppers, true bugs, and beetles.[13] The seeds of grasses are the mainstay of its diet during the winter, although buds and insects are eaten when available. The young are fed mainly insects at first, to provide them with protein.[22] The indigo bunting does not drink frequently, generally obtaining sufficient water from its diet.[13]

Predators and parasites

[edit]Indigo bunting nests are vulnerable to a variety of climbing and flying predators, including Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana), red fox (Vulpes vulpes), domestic cat (Felis catus), blue jay (Cyanocitta cristata), eastern racer (Coluber constrictor) and raccoon (Procyon lotor).[22] The bird is also susceptible to parasitism by louse flies.[29]

Conservation status

[edit]The criteria for a change in conservation status are a decline of more than 30% in ten years or over three generations.[19] The species is classified as being of least concern according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, with an estimated range of 5,900,000 km2 (2,300,000 sq mi) and a population of 28 million individuals. Global population trends have not been quantified, but the species is not believed to approach the thresholds for a population decline warranting an upgrade in conservation status.[19]

References

[edit]- ^ BirdLife International (2018). "Passerina cyanea". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22723951A132171198. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22723951A132171198.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ "Passerina cyanea". Integrated Taxonomic Information Systems. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- ^ Whitaker, William. "Passer". Words by William Whitaker. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- ^ Payne, Robert B. (February 4, 2020). "Indigo Bunting (Passerina cyanea), version 1.0". Birds of the World. doi:10.2173/bow.indbun.01 – via birdsoftheworld.org.

- ^ Sharpe, Roger S.; W. Ross Silcock; Joel G. Jorgensen (2001). Birds of Nebraska: Their Distribution and Temporal Occurrence. University of Nebraska Press. p. 430. ISBN 0-8032-4289-1.

- ^ Campbell, Robert Wayne (2001). The Birds of British Columbia. UBC Press. p. 184. ISBN 0-7748-0621-4.

- ^ Klicka, J; Fry AJ; Zink RM; Thompson CW (April 2001). "A Cytochrome-b Perspective on Passerina Bunting Relationships" (PDF). The Auk. 118 (3): 610–623. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2001)118[0610:ACBPOP]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 407700. Retrieved 14 July 2008.

- ^ a b Terres, J. K. (1980). The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds. New York, NY: Knopf. pp. 290. ISBN 0-394-46651-9.

- ^ a b c d e "Indigo Bunting". All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 2003. Archived from the original on 2006-04-13. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- ^ CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses by John B. Dunning Jr. (Editor). CRC Press (1992), ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- ^ Gough, Gregory (2003). "Passerina cyanea". USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. Archived from the original on 2021-11-13. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- ^ "Passerina cyanea". Audubon Society. 2003. Archived from the original on 2008-06-10. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

- ^ a b c d e Zumberg, R (1999). "Passerina cyanea". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Archived from the original on 2021-11-13. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- ^ Johnston, David W. (1967). "The Identification of Autumnal Indigo Buntings". Bird-Banding. 38 (3): 211–214. doi:10.2307/4511386. ISSN 0006-3630. JSTOR 4511386.

- ^ "Indigo Bunting Overview, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Archived from the original on 2021-11-13. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ a b Blake, Charles H. (1969). "Notes on the Indigo Bunting". Bird-Banding. 40 (2): 133–139. doi:10.2307/4511557. ISSN 0006-3630. JSTOR 4511557.

- ^ Sibley, Charles Gald; Burt Leavelle Monroe (1991). Distribution and Taxonomy of Birds of the World. Yale University Press. p. 775. ISBN 0-300-04969-2.

- ^ a b c d Johnston, David W. (1965). "Ecology of the Indigo Bunting in Florida". Quarterly Journal of the Florida Academy of Sciences. 28 (2): 199–211. ISSN 0015-3850. JSTOR 24314739.

- ^ a b c "Indigo Bunting (Passerina cyanea) - BirdLife species factsheet". datazone.birdlife.org. Archived from the original on 2021-11-13. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ^ Eliott, Lang (2004). Know Your Bird Sounds. Stackpole Books. p. 23. ISBN 0-8117-2964-8.

- ^ Kaufman, Kenneth (2001). Birds of North America. HMCo Field Guides. p. 366. ISBN 0-618-13219-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Kaufman, Kenneth (2001). Lives of North American Birds. HMCo Field Guides. p. 569. ISBN 0-618-15988-6.

- ^ Emlen, Stephen T. (October 1967). "Migratory Orientation in the Indigo Bunting, Passerina cyanea – Part II: Mechanism of Celestial Orientation" (PDF). The Auk. 84 (4): 463–489. doi:10.2307/4083330. JSTOR 4083330. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- ^ Emlen, Stephen T. (1967). "Migratory Orientation in the Indigo Bunting, Passerina cyanea: Part I: Evidence for Use of Celestial Cues". The Auk. 84 (3): 309–342. doi:10.2307/4083084. ISSN 0004-8038. JSTOR 4083084.

- ^ Emlen, Stephen T. (1967-10-01). "Migratory Orientation in the Indigo Bunting, Passerina cyanea. Part II: Mechanism of Celestial Orientation". The Auk. 84 (4): 463–489. doi:10.2307/4083330. JSTOR 4083330.

- ^ Harrison, Hal H. (2001). A Field Guide to Western Birds' Nests. HMCo Field Guides. p. 231. ISBN 0-618-16437-5.

- ^ Fergus, Charles (2000). Wildlife of Pennsylvania and the Northeast. Stackpole Books. pp. 316–317. ISBN 0-8117-2899-4.

- ^ Johnsgard, Paul A. (1997). The Avian Brood Parasites: Deception at the Nest. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 349. ISBN 0-19-511042-0.

- ^ Payne, R. (1992). The Birds of North America (no 4).

External links

[edit]- "Indigo bunting media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Indigo bunting photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Indigo bunting bird sound at Florida Museum of Natural History