Problem of two emperors

The problem of two emperors or two-emperor problem (deriving from the German term Zweikaiserproblem, Template:Lang-el)[1] is the historiographical term for the historical contradiction between the idea of the universal empire, that there was only ever one true emperor at any one given time, and the truth that there were often multiple individuals who claimed the position simultaneously. The term is primarily used in regards to medieval European history and often refers to in particular the long-lasting dispute between the Byzantine emperors in Constantinople and the Holy Roman emperors in modern-day Germany and Austria as to which monarch represented the legitimate Roman emperor.

In the view of medieval Christians, the Roman Empire was indivisible and its emperor held a somewhat hegemonic position even over Christians who did not live within the formal borders of the empire. Since the collapse of the Western Roman Empire during late antiquity, the Byzantine Empire (which represented its surviving provinces in the East) had been recognized as the legitimate Roman Empire by itself, the pope, and the various new Christian kingdoms throughout Europe. This changed in 797 when Emperor Constantine VI was deposed, blinded, and replaced as ruler by his mother, Empress Irene, whose rule was ultimately not accepted in Western Europe, the most frequently cited reason being that she was a woman. Rather than recognizing Irene, Pope Leo III proclaimed the king of the Franks, Charlemagne, as the emperor of the Romans in 800 under the concept of translatio imperii (transfer of imperial power).

Although the two empires eventually relented and recognized each other's rulers as emperors, they never explicitly recognized the other as "Roman", with the Byzantines referring to the Holy Roman emperor as the 'emperor (or king) of the Franks' and later as the 'king of Germany' and the western sources often describing the Byzantine emperor as the 'emperor of the Greeks' or the 'emperor of Constantinople'. Over the course of the centuries after Charlemagne's coronation, the dispute in regards to the imperial title was one of the most contested issues in Holy Roman–Byzantine politics. Though military action rarely resulted because of it, the dispute significantly soured diplomacy between the two empires. This lack of war was probably mostly on account of the geographical distance between the two empires. On occasion, the imperial title was claimed by neighbors of the Byzantine Empire, such as Bulgaria and Serbia, which often led to military confrontations.

After the Byzantine Empire was momentarily overthrown by the Catholic crusaders of the Fourth Crusade in 1204 and supplanted by the Latin Empire, the dispute continued even though both emperors now followed the same religious head for the first time since the dispute began. Though the Latin emperors recognized the Holy Roman emperors as the legitimate Roman emperors, they also claimed the title for themselves, which was not recognized by the Holy Roman Empire in return. Pope Innocent III eventually accepted the idea of divisio imperii (division of empire), in which imperial hegemony would be divided into West (the Holy Roman Empire) and East (the Latin Empire). Although the Latin Empire was destroyed by the resurgent Byzantine Empire under the Palaiologos dynasty in 1261, the Palaiologoi never reached the power of the pre-1204 Byzantine Empire and its emperors ignored the problem of two emperors in favor of closer diplomatic ties with the west due to a need for aid against the many enemies of their empire.

The problem of two emperors only fully resurfaced after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, after which the Ottoman sultan Mehmed II claimed the imperial dignity as Kayser-i Rûm (Caesar of the Roman Empire) and aspired to claim universal hegemony. The Ottoman sultans were recognized as emperors by the Holy Roman Empire in the 1533 Treaty of Constantinople, but the Holy Roman emperors were not recognized as emperors in turn. The Ottomans called the Holy Roman emperors by the title kıral (king) for one and a half centuries, until the Sultan Ahmed I formally recognized Emperor Rudolf II as an emperor in the Peace of Zsitvatorok in 1606, an acceptance of divisio imperii, bringing an end to the dispute between Constantinople and Western Europe. In addition to the Ottomans, the Tsardom of Russia and the later Russian Empire also claimed the Roman legacy of the Byzantine Empire, with its rulers titling themselves as tsar (deriving from "caesar") and later imperator. Their claim to the imperial title was not recognized by the Holy Roman Empire until 1745.

Background

Political background

Following the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, Roman civilization endured in the remaining eastern half of the Roman Empire, often termed by historians as the Byzantine Empire (though it self-identified simply as the "Roman Empire"). As the Roman emperors had done in antiquity, the Byzantine emperors saw themselves as universal rulers. The idea was that the world contained one empire (the Roman Empire) and one church and this idea survived despite the collapse of the empire's western provinces. Although the last extensive attempt at putting the theory back into practice had been Justinian I's wars of reconquest in the 6th century, which saw the return of Italy and Africa into imperial control, the idea of a great western reconquest remained a dream for Byzantine emperors for centuries.[2]

Because the empire was constantly threatened at critical frontiers to its north and east, the Byzantines were unable to focus much attention to the west and Roman control would slowly disappear in the west once more. Nevertheless, their claim to the universal empire was acknowledged by temporal and religious authorities in the west, even if this empire couldn't be physically restored. Gothic and Frankish kings in the fifth and sixth centuries acknowledged the emperor's suzerainty, as a symbolic acknowledgement of membership in the Roman Empire also enhanced their own status and granted them a position in the perceived world order of the time. As such, Byzantine emperors could still perceive the west as the western part of their empire, momentarily in barbarian hands, but still formally under their control through a system of recognition and honors bestowed on the western kings by the emperor.[2]

A decisive geopolitical turning point in the relations between East and West was during the long reign of emperor Constantine V (741–775). Though Constantine V conducted several successful military campaigns against the enemies of his empire, his efforts were centered on the Muslims and the Bulgars, who represented immediate threats. Because of this, the defense of Italy was neglected. The main Byzantine administrative unit in Italy, the Exarchate of Ravenna, fell to the Lombards in 751, ending the Byzantine presence in northern Italy.[3] The collapse of the Exarchate had long-standing consequences. The popes, ostensibly Byzantine vassals, realized that Byzantine support was no longer a guarantee and increasingly began relying on the major kingdom in the West, the Frankish Kingdom, for support against the Lombards. Byzantine possessions throughout Italy, such as Venice and Naples, began to raise their own militias and effectively became independent. Imperial authority ceased to be exercised in Corsica and Sardinia and religious authority in southern Italy was formally transferred by the emperors from the popes to the patriarchs of Constantinople. The Mediterranean world, interconnected since the days of Roman Empire of old, had been definitely divided into East and West.[4]

In 797 the young emperor Constantine VI was arrested, deposed and blinded by his mother and former regent, Irene of Athens. She then governed the empire as its sole ruler, taking the title Basileus rather than the feminine form Basilissa (used for the empresses who were wives of reigning emperors). At the same time, the political situation in the West was rapidly changing. The Frankish Kingdom had been reorganized and revitalized under king Charlemagne.[5] Though Irene had been on good terms with the papacy prior to her usurpation of the Byzantine throne, the act soured her relations with Pope Leo III. At the same time, Charlemagne's courtier Alcuin had suggested that the imperial throne was now vacant since a woman claimed to be emperor, perceived as a symptom of the decadence of the empire in the east.[6] Possibly inspired by these ideas and possibly viewing the idea of a woman emperor as an abomination, Pope Leo III also began to see the imperial throne as vacant. When Charlemagne visited Rome for Christmas in 800 he was treated not as one territorial ruler among others, but as the sole legitimate monarch in Europe and on Christmas Day he was proclaimed and crowned by Pope Leo III as the Emperor of the Romans.[5]

Rome and the idea of the Universal Empire

Though the Roman Empire is an example of a universal monarchy, the idea is not exclusive to the Romans, having been expressed in unrelated entities such as the Aztec Empire and in earlier realms such as the Persian and Assyrian Empires.[7]

Most "universal monarchs" justified their ideology and actions through the divine; proclaiming themselves (or being proclaimed by others) as either divine themselves or as appointed on the behalf of the divine, meaning that their rule was theoretically sanctioned by heaven. By tying together religion with the empire and its ruler, obedience to the empire became the same thing as obedience to the divine. Like its predecessors, the Ancient Roman religion functioned in much the same way, conquered peoples were expected to participate in the imperial cult regardless of their faith before Roman conquest. This imperial cult was threatened by religions such as Christianity (where Jesus Christ is explicitly proclaimed as the "Lord"), which is one of the primary reasons for the harsh persecutions of Christians during the early centuries of the Roman Empire; the religion was a direct threat to the ideology of the regime. Although Christianity eventually became the state religion of the Roman Empire in the 4th century, the imperial ideology was far from unrecognizable after its adoption. Like the previous imperial cult, Christianity now held the empire together and though the emperors were no longer recognized as gods, the emperors had successfully established themselves as the rulers of the Christian church in the place of Christ, still uniting temporal and spiritual authority.[7]

In the Byzantine Empire, the authority of the emperor as both the rightful temporal ruler of the Roman Empire and the head of Christianity remained unquestioned until the fall of the empire in the 15th century.[8] The Byzantines firmly believed that their emperor was God's appointed ruler and his viceroy on Earth (illustrated in their title as Deo coronatus, "crowned by God"), that he was the Roman emperor (basileus ton Rhomaion), and as such the highest authority in the world due to his universal and exclusive emperorship. The emperor was an absolute ruler dependent on no one when exercising his power (illustrated in their title as autokrator, or the Latin moderator).[9] The Emperor was adorned with an aura of holiness and was theoretically not accountable to anyone but God himself. The Emperor's power, as God's viceroy on Earth, was also theoretically unlimited. In essence, Byzantine imperial ideology was simply a christianization of the old Roman imperial ideology, which had also been universal and absolutist.[10]

As the Western Roman Empire collapsed and subsequent Byzantine attempts to retain the west crumbled, the church took the place of the empire in the west and by the time Western Europe emerged from the chaos endured during the 5th to 7th centuries, the pope was the chief religious authority and the Franks were the chief temporal authority. Charlemagne's coronation as Roman emperor expressed an idea different from the absolutist ideas of the emperors in the Byzantine Empire. Though the eastern emperor retained control of both the temporal empire and the spiritual church, the rise of a new empire in the west was a collaborative effort, Charlemagne's temporal power had been won through his wars, but he had received the imperial crown from the pope. Both the emperor and the pope had claims to ultimate authority in Western Europe (the popes as the successors of Saint Peter and the emperors as divinely appointed protectors of the church) and though they recognized the authority of each other, their "dual rule" would give rise to many controversies (such as the Investiture Controversy and the rise and fall of several antipopes).[8]

Holy Roman–Byzantine dispute

Carolingian period

Imperial ideology

Though the inhabitants of the Byzantine Empire itself never stopped referring to themselves as "Romans" (Rhomaioi), sources from Western Europe from the coronation of Charlemagne and onwards denied the Roman legacy of the eastern empire by referring to its inhabitants as "Greeks". The idea behind this renaming was that Charlemagne's coronation did not represent a division (divisio imperii) of the Roman Empire into West and East nor a restoration (renovatio imperii) of the old Western Roman Empire. Rather, Charlemagne's coronation was the transfer (translatio imperii) of the imperium Romanum from the Greeks in the east to the Franks in the west.[11] To contemporaries in Western Europe, Charlemagne's key legitimizing factor as emperor (other than papal approval) was the territories which he controlled. As he controlled formerly Roman lands in Gaul, Germany and Italy (including Rome itself), and acted as a true emperor in these lands, which the eastern emperor was seen as having had abandoned, he thus deserved to be called an emperor.[12]

Although crowned as an explicit refusal of the eastern emperor's claim to universal rule, Charlemagne himself does not appear to have been interested in confrontation with the Byzantine Empire or its rulers.[12] When Charlemagne was crowned by Pope Leo III, the title he was bestowed with was simply Imperator.[13] When he wrote to Constantinople in 813, Charlemagne titled himself as the "emperor and augustus and also king of the Franks and of the Lombards", identifying the imperial title with his previous royal titles in regards to the Franks and Lombards, rather than to the Romans. As such, his imperial title could be seen as stemming from the fact that he was the king of more than one kingdom (equating the title of emperor with that of king of kings), rather than as an usurpation of Byzantine power.[12]

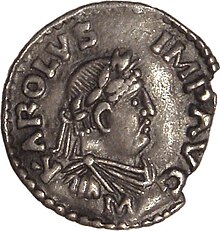

On his coins, the name and title used by Charlemagne is Karolus Imperator Augustus and in his own documents he used Imperator Augustus Romanum gubernans Imperium ("august emperor, governing the Roman Empire") and serenissimus Augustus a Deo coronatus, magnus pacificus Imperator Romanorum gubernans Imperium ("most serene Augustus crowned by God, great peaceful emperor governing the empire of the Romans").[13] The identification as an "emperor governing the Roman Empire" rather than a "Roman emperor" could be seen as an attempt at avoiding the dispute and issue over who was the true emperor and attempting to keep the perceived unity of the empire intact.[12]

In response to the Frankish adoption of the imperial title, the Byzantine emperors (which had previously simply used "emperor" as a title) adopted the full title of "emperor of the Romans" to make their supremacy clear.[13] To the Byzantines, Charlemagne's coronation was a rejection of their perceived order of the world and an act of usurpation. Although Emperor Michael I eventually relented and recognized Charlemagne as an emperor and a "spiritual brother" of the eastern emperor, Charlemagne was not recognized as the Roman emperor and his imperium was seen as limited to his actual domains (as such not universal) and not as something that would outlive him (with his successors being referred to as "kings" rather than emperors in Byzantine sources).[14]

Following Charlemagne's coronation, the two empires engaged in diplomacy with each other. The exact terms discussed are unknown and negotiations were slow but it seems that Charlemagne proposed in 802 that he and Irene would marry and unite their empires.[15] As such, the empire could have "reunited" without arguments as to which ruler was the legitimate one.[12] This plan failed however, as the message only arrived in Constantinople after Irene had been deposed and exiled by a new emperor, Nikephoros I.[15]

Louis II and Basil I

One of the primary resources in regards to the problem of two emperors in the Carolingian period is a letter by Emperor Louis II. Louis II was the fourth emperor of the Carolingian Empire, though his domain was confined to northern Italy as the rest of the empire had fractured into several different kingdoms, though these still acknowledged Louis as the emperor. His letter was a reply to a provocative letter by Byzantine emperor Basil I. Though Basil's letter is lost, its contents can be ascertained from the known geopolitical situation at the time and Louis's reply and probably related to the ongoing co-operation between the two empires against the Muslims. The focal point of Basil's letter was his refusal to recognize Louis II as a Roman emperor.[16]

Basil appears to have based his refusal on two main points. First of all, the title of Roman emperor was not hereditary (the Byzantines still considered it to formally be a republican office, although also tied intimately with religion) and second of all, it was not considered appropriate for someone of a gens (e.g. an ethnicity) to hold the title. The Franks, and other groups throughout Europe, were seen as different gentes but to Basil and the rest of the Byzantines, "Roman" was not a gens. Romans were defined chiefly by their lack of a gens and as such, Louis was not Roman and thus not a Roman emperor. There was only one Roman emperor, Basil himself, and though Basil considered that Louis could be an emperor of the Franks, he appears to have questioned this as well seeing as only the ruler of the Romans was to be titled basileus (emperor).[16]

As illustrated by Louis's letter, the western idea of ethnicity was different from the Byzantine idea; everyone belonged to some form of ethnicity. Louis considered the gens romana (Roman people) to be the people who lived in the city of Rome, which he saw as having been deserted by the Byzantine Empire. All gentes could be ruled by a basileus in Louis's mind and as he pointed out, the title (which had originally simply meant "king") had been applied to other rulers in the past (notably Persian rulers). Furthermore, Louis disagreed with the notion that someone of a gens could not become the Roman emperor. He considered the gentes of Hispania (the Theodosian dynasty), Isauria (the Isaurian dynasty), and Khazaria (Leo IV) as all having provided emperors, though the Byzantines themselves would have seen all of these as Romans and not as peoples of gentes. The views expressed by the two emperors in regards to ethnicity are somewhat paradoxical; Basil defined the Roman Empire in ethnic terms (defining it as explicitly against ethnicity) despite not considering the Romans as an ethnicity and Louis did not define the Roman Empire in ethnic terms (defining it as an empire of God, the creator of all ethnicities) despite considering the Romans as an ethnic people.[16]

Louis also derived legitimacy from religion. He argued that as the Pope of Rome, who actually controlled the city, had rejected the religious leanings of the Byzantines as heretical and instead favored the Franks and because the Pope had also crowned him emperor, Louis was the legitimate Roman emperor. The idea was that it was God himself, acting through his vicar the Pope, who had granted the church, people and city of Rome to him to govern and protect.[16] Louis's letter details that if he was not the emperor of the Romans then he could not be the emperor of the Franks either, as it was the Roman people themselves who had accorded his ancestors with the imperial title. In contrast to the papal affirmation of his imperial lineage, Louis chastized the eastern empire for its emperors mostly only being affirmed by their senate and sometimes lacking even that, with some emperors having been proclaimed by the army, or worse, women (probably a reference to Irene). Louis probably overlooked that affirmation by the army was the original ancient source for the title of imperator, before it came to mean the ruler of the Roman Empire.[17]

Though it would have been possible for either side of the dispute to concede to the obvious truth, that there were now two empires and two emperors, this would have denied the understood nature of what the empire was and meant (its unity).[12] Louis's letter does offer some evidence that he might have recognized the political situation as such; Louis is referred to as the "august emperor of the Romans" and Basil is referred to as the "very glorious and pious emperor of New Rome",[18] and he suggests that the "indivisible empire" is the empire of God and that "God has not granted this church to be steered either by me or you alone, but so that we should be bound to each other with such love that we cannot be divided, but should seem to exist as one".[16] These references are more likely to mean that Louis still considered there to be a single empire, but with two imperial claimants (in effect an emperor and an anti-emperor). Neither side in the dispute would have been willing to reject the idea of the single empire. Louis referring to the Byzantine emperor as an emperor in the letter may simply be a courtesy, rather than an implication that he truly accepted his imperial rule.[19]

Louis's letter mentions that the Byzantines abandoned Rome, the seat of empire, and lost the Roman way of life and the Latin language. In his view, that the empire was ruled from Constantinople did not represent it surviving, but rather that it had fled from its responsibilities.[18] Although he would have had to approve its contents, Louis probably did not write his letter himself and it was probably instead written by the prominent cleric Anastasius Bibliothecarius. Anastasius was not a Frank but a citizen of the city of Rome (in Louis's view an "ethnic Roman"). As such, prominent figures in Rome itself would have shared Louis's views, illustrating that by his time, the Byzantine Empire and the city of Rome had drifted very far apart.[16]

Following the death of Louis in 875, emperors continued to be crowned in the West for a few decades, but their reigns were often brief and problematic and they only held limited power and as such the problem of two emperors ceased being a major issue to the Byzantines, for a time.[20]

Ottonian period

The problem of two emperors returned when Pope John XII crowned the king of Germany, Otto I, as emperor of the Romans in 962, almost 40 years after the death of the previous papally crowned emperor, Berengar. Otto's repeated territorial claims to all of Italy and Sicily (as he had also been proclaimed as the king of Italy) brought him into conflict with the Byzantine Empire.[21] The Byzantine emperor at the time, Romanos II, appears to have more or less ignored Otto's imperial aspirations, but the succeeding Byzantine emperor, Nikephoros II, was strongly opposed to them. Otto, who hoped to secure imperial recognition and the provinces in southern Italy diplomatically through a marriage alliance, dispatched diplomatic envoys to Nikephoros in 967.[20] To the Byzantines, Otto's coronation was a blow as, or even more, serious than Charlemagne's as Otto and his successors insisted on the Roman aspect of their imperium more strongly than their Carolingian predecessors.[22]

Leading Otto's diplomatic mission was Liutprand of Cremona, who chastized the Byzantines for their perceived weakness; losing control of the West and thus also causing the pope to lose control of the lands which belonged to him. To Liutprand, the fact that Otto I had acted as a restorer and protector of the church by restoring the lands of the papacy (which Liutprand believed had been granted to the pope by Emperor Constantine I), made him the true emperor while the loss of these lands under preceding Byzantine rule illustrated that the Byzantines were weak and unfit to be emperors.[19] Liutprand expresses his ideas with the following words in his report on the mission, in a reply to Byzantine officials:[23]

My master did not by force or tyrannically invade the city of Rome; but he freed it from a tyrant, nay, from the yoke of tyrants. Did not the slaves of women rule over it; or, which is worse and more disgraceful, harlots themselves? Your power, I fancy, or that of your predecessors, who in name alone are called emperors of the Romans and are it not in reality, was sleeping at that time. If they were powerful, if emperors of the Romans, why did they permit Rome to be in the hands of harlots? Were not some of them most holy popes banished, others so oppressed that they were not able to have their daily supplies or the means of giving alms? Did not Adalbert send scornful letters to the emperors Romanus and Constantine your predecessors? Did he not plunder the churches of the most holy apostles? What one of you emperors, led by zeal for God, took care to avenge so unworthy a crime and to bring back the holy church to its proper conditions? You neglected it, my master did not neglect it. For, rising from the ends of the earth and coming to Rome, he removed the impious and gave back to the vicars of the holy apostles their power and all their honor...

Nikephoros pointed out to Liutprand personally that Otto was a mere barbarian king who had no right to call himself an emperor, nor to call himself a Roman.[24] Just before Liutprand's arrival in Constantinople, Nikephoros II had received an offensive letter from Pope John XIII, possibly written under pressure from Otto, in which the Byzantine emperor was referred to as the "Emperor of the Greeks" and not the "Emperor of the Romans", denying his true imperial status. Liutprand recorded the outburst of Nikephoros's representatives at this letter, which illustrates that the Byzantines too had developed an idea similar to translatio imperii regarding the transfer of power from Rome to Constantinople:[19]

Hear then! The silly pope does not know that the holy Constantine transferred hither the imperial sceptre, the senate, and all the Roman knighthood, and left in Rome nothing but vile minions – fishers, namely, pedlars, bird catchers, bastards, plebeians, slaves.

Liutprand attempted to diplomatically excuse the pope by stating that the pope had believed that the Byzantines would not like the term "Romans" since they had moved to Constantinople and changed their customs and assured Nikephoros that in the future, the eastern emperors would be addressed in papal letters as "the great and august emperor of the Romans".[25] Otto's attempted cordial relations with the Byzantine Empire would be hindered by the problem of the two emperors, and the eastern emperors were less than eager to reciprocate his feelings.[23] Liutprand's mission to Constantinople was a diplomatic disaster, and his visit saw Nikephoros repeatedly threaten to invade Italy, restore Rome to Byzantine control and on one occasion even threaten to invade Germany itself, stating (concerning Otto) that "we will arouse all the nations against him; and we will break him in pieces like a potter's vessel".[23] Otto's attempt at a marriage alliance would not materialize until after Nikephoros's death. In 972, in the reign of Byzantine emperor John I Tzimiskes, a marriage was secured between Otto's son and co-emperor Otto II and John's niece Theophanu.[21]

Though Emperor Otto I briefly used the title imperator augustus Romanorum ac Francorum ("august emperor of Romans and Franks") in 966, the style he used most commonly was simply Imperator Augustus. Otto leaving out any mention of Romans in his imperial title may be because he wanted to achieve the recognition of the Byzantine emperor. Following Otto's reign, mentions of the Romans in the imperial title became more common. In the 11th century, the German king (the title held by those who were later crowned emperors) was referred to as the rex Romanorum ("king of the Romans") and in the century after that, the standard imperial title was dei gratia Romanorum Imperator semper Augustus ("by the Grace of God, emperor of the Romans, ever august").[13]

Hohenstaufen period

To Liutprand of Cremona and later scholars in the west, the eastern emperors were perceived as weak, degenerate, and not true emperors; there was, they felt, a single empire under the true emperors (Otto I and his successors), who demonstrated their right to the empire through their restoration of the Church. In return, the eastern emperors did not recognize the imperial status of their challengers in the west. Although Michael I had referred to Charlemagne by the title Basileus in 812, he hadn't referred to him as the Roman emperor. Basileus in of itself was far from an equal title to that of Roman emperor. In their own documents, the only emperor recognized by the Byzantines was their own ruler, the Emperor of the Romans. In Anna Komnene's The Alexiad (c. 1148), the Emperor of the Romans is her father, Alexios I, while the Holy Roman emperor Henry IV is titled simply as the "King of Germany".[25]

In the 1150s, the Byzantine emperor Manuel I Komnenos became involved in a three-way struggle between himself, the Holy Roman emperor Frederick I Barbarossa and the Italo-Norman King of Sicily, Roger II. Manuel aspired to lessen the influence of his two rivals and at the same time win the recognition of the Pope (and thus by extension Western Europe) as the sole legitimate emperor, which would unite Christendom under his sway. Manuel reached for this ambitious goal by financing a league of Lombard towns to rebel against Frederick and encouraging dissident Norman barons to do the same against the Sicilian king. Manuel even dispatched his army to southern Italy, the last time a Byzantine army ever set foot in Western Europe. Despite his efforts, Manuel's campaign ended in failure and he won little except the hatred of both Barbarossa and Roger, who by the time the campaign concluded had allied with each other.[26]

Frederick Barbarossa's crusade

Soon after the conclusion of the Byzantine–Norman wars in 1185, the Byzantine emperor Isaac II Angelos received word that a Third Crusade had been called due to Sultan Saladin's 1187 conquest of Jerusalem. Isaac learnt that Barbarossa, a known foe of his empire, was to lead a large contingent in the footprints of the First and Second crusades through the Byzantine Empire. Isaac II interpreted Barbarossa's march through his empire as a threat and considered it inconceivable that Barbarossa did not also intend to overthrow the Byzantine Empire.[27] As a result of his fears, Isaac II imprisoned numerous Latin citizens in Constantinople.[28] In his treaties and negotiations with Barbarossa (which exist preserved as written documents), Isaac II was insincere as he had secretly allied with Saladin to gain concessions in the Holy Land and had agreed to delay and destroy the German army.[28]

Barbarossa, who did not in fact intend to take Constantinople, was unaware of Isaac's alliance with Saladin but still wary of the rival emperor. As such he sent out an embassy in early 1189, headed by the Bishop of Münster.[28] Isaac was absent at the time, putting down a revolt in Philadelphia, and returned to Constantinople a week after the German embassy arrived, after which he immediately had the Germans imprisoned. This imprisonment was partly motivated by Isaac wanting to possess German hostages, but more importantly, an embassy from Saladin, probably noticed by the German ambassadors, was also in the capital at this time.[29]

On 28 June 1189, Barbarossa's crusade reached the Byzantine borders, the first time a Holy Roman emperor personally set foot within the borders of the Byzantine Empire. Although Barbarossa's army was received by the closest major governor, the governor of Branitchevo, the governor had received orders to stall or, if possible, destroy the German army. On his way to the city of Niš, Barbarossa was repeatedly assaulted by locals under the orders of the governor of Branitchevo and Isaac II also engaged in a campaign of closing roads and destroying foragers.[29] The attacks against Barbarossa amounted to little and only resulted in around a hundred losses. A more serious issue was a lack of supplies, since the Byzantines refused to provide markets for the German army. The lack of markets was excused by Isaac as due to not having received advance notice of Barbarossa's arrival, a claim rejected by Barbarossa, who saw the embassy he had sent earlier as notice enough. Despite these issues, Barbarossa still apparently believed that Isaac was not hostile against him and refused invitations from the enemies of the Byzantines to join an alliance against them. While at Niš he was assured by Byzantine ambassadors that though there was a significant Byzantine army assembled near Sofia, it had been assembled to fight the Serbs and not the Germans. This was a lie, and when the Germans reached the position of this army, they were treated with hostility, though the Byzantines fled at the first charge of the German cavalry.[30]

Isaac II panicked and issued contradictory orders to the governor of the city of Philippopolis, one of the strongest fortresses in Thrace. Fearing that the Germans were to use the city as a base of operations, its governor, Niketas Choniates (later a major historian of these events), was first ordered to strengthen the city's walls and hold the fortress at all costs, but later to abandon the city and destroy its fortifications. Isaac II seems to have been unsure of how to deal with Barbarossa. Barbarossa meanwhile wrote to the main Byzantine commander, Manuel Kamytzes, that "resistance was in vain", but also made clear that he had absolutely no intention to harm the Byzantine Empire. On 21 August, a letter from Isaac II reached Barbarossa, who was encamped outside Philippopolis. In the letter, which caused great offense, Isaac II explicitly called himself the "Emperor of the Romans" in opposition to Barbarossa's title and the Germans also misinterpreted the Byzantine emperor as calling himself an angel (on account of his last name, Angelos). Furthermore, Isaac II demanded half of any territory to be conquered from the Muslims during the crusade and justified his actions by claiming that he had heard from the governor of Branitchevo that Barbarossa had plans to conquer the Byzantine Empire and place his son Frederick of Swabia on its throne. At the same time Barbarossa learnt of the imprisonment of his earlier embassy.[31] Several of Barbarossa's barons suggested that they take immediate military action against the Byzantines, but Barbarossa preferred a diplomatic solution.[32]

In the letters exchanged between Isaac II and Barbarossa, neither side titled the other in the way they considered to be appropriate. In his first letter, Isaac II referred to Barbarossa simply as the "King of Germany". The Byzantines eventually realized that the "wrong" title hardly improved the tense situation and in the second letter Barbarossa was called "the most high-born Emperor of Germany". Refusing to recognize Barbarossa as the Roman emperor, the Byzantines eventually relented with calling him "the most noble emperor of Elder Rome" (as opposed to the New Rome, Constantinople). The Germans always referred to Isaac II as the Greek emperor or the Emperor of Constantinople.[33]

The Byzantines continued to harass the Germans. The wine left behind in the abandoned city of Philippopolis had been poisoned, and a second embassy sent from the city to Constantinople by Barbarossa was also imprisoned, though shortly thereafter Isaac II relented and released both embassies. When the embassies reunited with Barbarossa at Philippopolis they told the Holy Roman emperor of Isaac II's alliance with Saladin, and claimed that the Byzantine emperor intended to destroy the German army while it was crossing the Bosporus. In retaliation for spotting anti-Crusader propaganda in the surrounding region, the crusaders devastated the immediate area around Philippopolis, slaughtering the locals. After Barbarossa was addressed as the "King of Germany", he flew into a fit of rage, demanding hostages from the Byzantines (including Isaac II's son and family), asserting that he was the one true Emperor of the Romans and made it clear that he intended to winter in Thrace despite the Byzantine emperor's offer of assisting the German army to cross the Bosporus.[34]

By this point, Barbarossa had become convinced that Constantinople needed to be conquered in order for the crusade to be successful. On 18 November he sent a letter to his son, Henry, in which he explained to difficulties he had encountered and ordered his son to prepare for an attack against Constantinople, ordering the assembling of a large fleet to meet him in the Bosporus once spring came. Furthermore, Henry was instructed to ensure Papal support for such a campaign, organizing a great Western crusade against the Byzantines as enemies of God. Isaac II replied to Barbarossa's threats by claiming that Thrace would be Barbarossa's "deathtrap" and that it was too late for the German emperor to escape "his nets". As Barbarossa's army, reinforced with Serbian and Vlach allies, approached Constantinople, Isaac II's resolve faded and he began to favor peace instead.[35] Barbarossa had continued to send offers of peace and reconciliation since he had seized Philippopolis, and once Barbarossa officially sent a declaration of war in late 1189, Isaac II at last relented, realizing he wouldn't be able to destroy the German army and was at risk of losing Constantinople itself. The peace saw the Germans being allowed to pass freely through the empire, transportation across the Bosporus and the opening of markets as well as compensation for the damage done to Barbarossa's expedition by the Byzantines.[36] Frederick then continued on towards the Holy Land without any further major incidents with the Byzantines, with the exception of the German army almost sacking the city of Philadelphia after its governor refused to open up the markets to the Crusaders.[37] The incidents during the Third Crusade heightened animosity between the Byzantine Empire and the west. To the Byzantines, the devastation of Thrace and efficiency of the German soldiers had illustrated the threat they represented, while in the West, the mistreatment of the emperor and the imprisonment of the embassies would be long remembered.[38]

Threats of Henry VI

Frederick Barbarossa died before reaching the Holy Land and his son and successor, Henry VI, pursued a foreign policy in which he aimed to force the Byzantine court to accept him as the superior (and sole legitimate) emperor.[39] By 1194, Henry had successfully consolidated Italy under his own rule after being crowned as King of Sicily, in addition to already being the Holy Roman emperor and the King of Italy, and he turned his gaze east. The Muslim world had fractured after Saladin's death and Barbarossa's crusade had revealed the Byzantine Empire to be weak and also given a useful casus belli for attack. Furthermore, Leo II, the ruler of Cilician Armenia, offered to swear fealty to Henry VI in exchange for being accorded a royal crown.[40] Henry bolstered his efforts against the eastern empire by marrying a captive daughter of Isaac II, Irene Angelina, to his brother Philip of Swabia in 1195, giving his brother a dynastic claim that could prove useful in the future.[41]

In 1195 Henry VI also dispatched an embassy to the Byzantine Empire, demanding from Isaac II that he transfer a stretch of land stretching from Durazzo to Thessalonica, previously conquered by the Sicilian king William II, and also wished the Byzantine emperor to promise naval support in preparation for a new crusade. According to Byzantine historians, the German ambassadors spoke as if Henry VI was the "emperor of emperors" and "lord of lords". Henry VI intended to force the Byzantines to pay him to ensure peace, essentially extracting tribute, and his envoys put forward the grievances that the Byzantines had caused throughout Barbarossa's reign. Not in a position to resist, Isaac II succeeded to modify the terms so that they were purely monetary. Shortly after agreeing to these terms, Isaac II was overthrown and replaced as emperor by his older brother, Alexios III Angelos.[42]

Henry VI successfully compelled Alexios III as well to pay tribute to him under the threat of otherwise conquering Constantinople on his way to the Holy Land.[43] Henry VI had grand plans of becoming the leader of the entire Christian world. Although he would only directly rule his traditional domains, Germany and Italy, his plans were that no other empire would claim ecumenical power and that all Europe was to recognize his suzerainty. His attempt to subordinate the Byzantine Empire to himself was just one step in his partially successful plan of extending his feudal overlordship from his own domains to France, England, Aragon, Cilician Armenia, Cyprus and the Holy Land.[44] Based on the establishment of bases in the Levant and the submission of Cilician Armenia and Cyprus, it is possible that Henry VI really considered invading and conquering the Byzantine Empire, thus uniting the rivalling empires under his rule. This plan, just as Henry's plan of making the position of emperor hereditary rather than elective, ultimately never transpired as he was kept busy by internal affairs in Sicily and Germany.[45]

The threat of Henry VI caused some concern in the Byzantine Empire and Alexios III slightly altered his imperial title to en Christoi to theo pistos basileus theostephes anax krataios huspelos augoustos kai autokrator Romaion in Greek and in Christo Deo fidelis imperator divinitus coronatus sublimis potens excelsus semper augustus moderator Romanorum in Latin. Though previous Byzantine emperors had used basileus kai autokrator Romaion ("Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans"), Alexios III's title separated basileus from the rest and replaced its position with augoustos (Augustus, the old Roman imperial title), creating the possible interpretation that Alexios III was simply an emperor (Basileus) and besides that also the moderator Romanorum ("Autocrat of the Romans") but not explicitly the Roman emperor, so that he was no longer in direct competition with his rival in Germany and that his title was less provocative to the West in general. Alexios III's successor, Alexios IV Angelos, continued with this practice and went even further, inverting the order of moderator Romanorum and rendering it as Romanorum moderator.[39]

The Latin Empire

A series of events and the intervention of Venice led to the Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) sacking Constantinople instead of attacking its intended target, Egypt. When the crusaders seized Constantinople in 1204, they founded the Latin Empire and called their new realm the imperium Constantinopolitanum, the same term used for the Byzantine Empire in Papal correspondence. This suggests that, although they had placed a new Catholic emperor, Baldwin I, on the throne of Constantinople and changed the administrative structure of the empire into a feudal network of counties, duchies and kingdoms, the crusaders viewed themselves as taking over the Byzantine Empire rather than replacing it with a new entity.[46] Notably Baldwin I was designated as an emperor, not a king. This is despite the fact that the crusaders, as Western Christians, would have recognized the Holy Roman Empire as the true Roman Empire and its ruler as the sole true emperor and that founding treaties of the Latin Empire explicitly designate the empire as in the service of the Roman Catholic Church.[47]

The rulers of the Latin Empire, although they seem to have called themselves Emperors of Constantinople (imperator Constantinopolitanus) or Emperors of Romania (imperator Romaniae, Romania being a Byzantine term meaning the "land of the Romans") in correspondence with the Papacy, used the same imperial titles within their own empire as their direct Byzantine predecessors, with the titles of the Latin Emperors (Dei gratia fidelissimus in Christo imperator a Deo coronatus Romanorum moderator et semper augustus) being near identical to the Latin version of the title of Byzantine emperor Alexios IV (fidelis in Christo imperator a Deo coronatus Romanorum moderator et semper augustus).[48] As such, the titles of the Latin emperors continued the compromise in titulature worked out by Alexios III.[39] In his seals, Baldwin I abbreviated Romanorum as Rom., a convenient and slight adjustment that left it open to interpretation if it truly referred to Romanorum or if it meant Romaniae.[48]

The Latin Emperors saw the term Romanorum or Romani in a new light, not seeing it as referring to the Western idea of "geographic Romans" (inhabitants of the city of Rome) but not adopting the Byzantine idea of the "ethnic Romans" (Greek-speaking citizens of the Byzantine Empire) either. Instead, they saw the term as a political identity encapsulating all subjects of the Roman emperor, i.e. all the subjects of their multi-national empire (whose ethnicities encompassed Latins, "Greeks", Armenians and Bulgarians).[49]

The embracing of the Roman nature of the emperorship in Constantinople would have brought the Latin emperors into conflict with the idea of translatio imperii. Furthermore, the Latin emperors claimed the dignity of Deo coronatus (as the Byzantine emperors had claimed before them), a dignity the Holy Roman emperors could not claim, being dependent on the Pope for their coronation. Despite the fact that the Latin emperors would have recognized the Holy Roman Empire as the Roman Empire, they nonetheless claimed a position that was at least equal to that of the Holy Roman emperors.[50] In 1207–1208, Latin emperor Henry proposed to marry the daughter of the elected rex Romanorum in the Holy Roman Empire, Henry VI's brother Philip of Swabia, yet to be crowned emperor due to an ongoing struggle with the rival claimant Otto of Brunswick. Philip's envoys responded that Henry was an advena (stranger; outsider) and solo nomine imperator (emperor in name only) and that the marriage proposal would only be accepted if Henry recognized Philip as the imperator Romanorum and suus dominus (his master). As no marriage occurred, it is clear that submission to the Holy Roman emperor was not considered an option.[51]

The emergence of the Latin Empire and the submission of Constantinople to the Catholic Church as facilitated by its emperors altered the idea of translatio imperii into what was called divisio imperii (division of empire). The idea, which became accepted by Pope Innocent III, saw the formal recognition of Constantinople as an imperial seat of power and its rulers as legitimate emperors, which could rule in tandem with the already recognized emperors in the West. The idea resulted in that the Latin emperors never attempted to enforce any religious or political authority in the West, but attempted to enforce a hegemonic religious and political position, similar to that held by the Holy Roman emperors in the West, over the lands in Eastern Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean, especially in regards to the Crusader states in the Levant, where the Latin emperors would oppose the local claims of the Holy Roman emperors.[51]

Restoration of the Byzantine Empire

With the Byzantine reconquest of Constantinople in 1261 under Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos, the Papacy suffered a loss of prestige and endured severe damage to its spiritual authority. Once more, the easterners had asserted their right not only to the position of Roman emperor but also to a church independent of the one centered in Rome. The popes who were active during Michael's reign all pursued a policy of attempting to assert their religious authority over the Byzantine Empire. As Michael was aware that the popes held considerable sway in the west (and wishing to avoid a repeat of the events of 1204), he dispatched an embassy to Pope Urban IV immediately after taking possession of the city. The two envoys were immediately imprisoned once they sat foot in Italy: one was flayed alive and the other managed to escape back to Constantinople.[52] From 1266 to his death in 1282, Michael would repeatedly be threatened by the King of Sicily, Charles of Anjou, who aspired to restore the Latin Empire and periodically enjoyed Papal support.[53]

Michael VIII and his successors, the Palaiologan dynasty, aspired to reunite the Eastern Orthodox Church with the Church of Rome, chiefly because Michael recognized that only the Pope could constrain Charles of Anjou. To this end, Byzantine envoys were present at the Second Council of Lyons in 1274, where the Church of Constantinople was formally reunified with Rome, restoring communion after more than two centuries.[54] On his return to Constantinople, Michael was taunted with the words "you have become a Frank", which remains a term in Greek to taunt converts to Catholicism to this day.[55] The Union of the Churches aroused passionate opposition from the Byzantine people, the Orthodox clergy, and even within the imperial family itself. Michael's sister Eulogia, and her daughter Anna, wife of the ruler of Epirus Nikephoros I Komnenos Doukas, were among the chief leaders of the anti-Unionists. Nikephoros, his half-brother John I Doukas of Thessaly, and even the Emperor of Trebizond, John II Megas Komnenos, soon joined the anti-Unionist cause and gave support to the anti-Unionists fleeing Constantinople.[56]

Nevertheless, the Union achieved Michael's main aim: it legitimized Michael and his successors as rulers of Constantinople in the eyes of the west. Furthermore, Michael's idea of a crusade to recover the lost portions of Anatolia received positive reception at the council, though such a campaign would never materialize.[57] The union was disrupted in 1281 when Michael was excommunicated, possibly due to Pope Martin IV having been pressured by Charles of Anjou.[58] Following Michael's death, and with the threat of an Angevin invasion having subsided following the Sicilian Vespers, his successor, Andronikos II Palaiologos, was quick to repudiate the hated Union of the Churches.[59] Although popes after Michael's death would periodically consider a new crusade against Constantinople to once more impose Catholic rule, no such plans materialized.[60]

Although Michael VIII, unlike his predecessors, did not protest when addressed as the "Emperor of the Greeks" by the popes in letters and at the Council of Lyons, his conception of his universal emperorship remained unaffected.[2] As late as 1395, when Constantinople was more or less surrounded by the rapidly expanding Ottoman Empire and it was apparent that its fall was a matter of time, Patriarch Antony IV of Constantinople still referenced the idea of the universal empire in a letter to the Grand Prince of Moscow, Vasily I, stating that anyone other than the Byzantine emperor assuming the title of "emperor" was "illegal" and "unnatural".[61]

Faced with the Ottoman danger, Michael's successors, prominently John V and Manuel II, periodically attempted to restore the Union, much to the dismay of their subjects. At the Council of Florence in 1439, Emperor John VIII reaffirmed the Union in the light of imminent Turkish attacks on what little remained of his empire. To the Byzantine citizens themselves, the Union of the Churches, which had assured the promise of a great western crusade against the Ottomans, was a death warrant for their empire. John VIII had betrayed their faith and as such their entire imperial ideology and world view. The promised crusade, the fruit of John VIII's labor, ended only in disaster as it was defeated by the Turks at the Battle of Varna in 1444.[62]

Byzantine–Bulgarian dispute

The dispute between the Byzantine Empire and the Holy Roman Empire was mostly confined to the realm of diplomacy, never fully exploding into open war. This was probably mainly due to the great geographical distance separating the two empires; a large-scale campaign would have been infeasible to undertake for either emperor.[63] Events in Germany, France and the west in general was of little compelling interest to the Byzantines as they firmly believed that the western provinces would eventually be reconquered.[64] Of more compelling interest were political developments in their near vicinity and in 913, the Knyaz (prince or king) of Bulgaria, Simeon I, arrived at the walls of Constantinople with an army. Simeon I's demands were not only that Bulgaria would be recognized as independent from the Byzantine Empire, but that it was to be designated as a new universal empire, absorbing and replacing the universal empire of Constantinople. Because of the threat represented, the Patriarch of Constantinople, Nicholas Mystikos, granted an imperial crown to Simeon. Simeon was designated as the Emperor of the Bulgarians, not of the Romans and as such, the diplomatic gesture had been somewhat dishonest.[63]

The Byzantines soon discovered that Simeon was in fact titling himself as not only the Emperor of the Bulgarians, but as the Emperor of the Bulgarians and the Romans. The problem was solved when Simeon died in 927 and his son and successor, Peter I, simply adopted Emperor of the Bulgarians as a show of submission to the universal empire of Constantinople. The dispute, deriving from Simeon's claim, would on occasion be revived by strong Bulgarian monarchs who once more adopted the title of Emperor of the Bulgarians and the Romans, such as Kaloyan (r. 1196–1207) and Ivan Asen II (r. 1218–1241).[64] Kaloyan attempted to receive recognition by Pope Innocent III as emperor, but Innocent refused, instead offering to provide a cardinal to crown him simply as king.[65] The dispute was also momentarily revived by the rulers of Serbia in 1346 with Stefan Dušan's coronation as Emperor of the Serbs and Romans.[64]

Holy Roman–Ottoman dispute

With the fall of Constantinople in 1453 and the rise of the Ottoman Empire in the Byzantine Empire's stead, the problem of two emperors returned.[66] Mehmed II, who had conquered the city, explicitly titled himself as the Kayser-i Rûm (Caesar of the Roman Empire), postulating a claim to world domination through the use of the Roman title. Mehmed deliberately linked himself to the Byzantine imperial tradition, making few changes in Constantinople itself and working on restoring the city through repairs and (sometimes forced) immigration, which soon led to an economic upswing. Mehmed also appointed a new Greek Orthodox patriarch, Gennadios, and began minting his own coins (a practice which the Byzantine emperors had engaged in, but the Ottomans never had previously). Furthermore, Mehmed introduced stricter court ceremonies and protocols inspired by those of the Byzantines.[67]

Contemporaries within the Ottoman Empire recognized Mehmed's assumption of the imperial title and his claim to world domination. The historian Michael Critobulus described the sultan as "emperor of emperors", "autocrat" and "Lord of the Earth and the sea according to God's will". In a letter to the doge of Venice, Mehmed was described by his courtiers as the "emperor". Other titles were sometimes used as well, such as "grand duke" and "prince of the Turkish Romans".[67] The citizens of Constantinople and the former Byzantine Empire (which still identified as "Romans" and not "Greeks" until modern times) saw the Ottoman Empire as still representing their empire, the universal empire; the imperial capital was still Constantinople and its ruler, Mehmed II, was the basileus.[68] As with the Byzantine emperors before them, the imperial status of the Ottoman sultans was primarily expressed through the refusal to recognize the Holy Roman emperors as equal rulers. In diplomacy, the western emperors were titled as kıral (kings) of Vienna or Hungary.[67] This practice had been cemented and reinforced by the Treaty of Constantinople in 1533, signed by the Ottoman Empire (under Suleiman I) and the Archduchy of Austria (as represented by Ferdinand I on behalf of Emperor Charles V), wherein it was agreed that Ferdinand I was to be considered as the king of Germany and Charles V as the king of Spain. These titles were considered to be equal in rank to the Ottoman Empire's grand vizier, subordinate to the imperial title held by the sultan. The treaty also banned its signatories to count anyone as an emperor except the Ottoman sultan.[69]

The problem of two emperors and the dispute between the Holy Roman Empire and the Ottoman Empire would be finally resolved after the two empires signed a peace treaty following a string of Ottoman defeats. In the 1606 Peace of Zsitvatorok Ottoman sultan Ahmed I, for the first time in his empire's history, formally recognized the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II with the title padishah (emperor) rather than kıral. Ahmed made sure to write "like a father to a son", symbolically emphasizing that the eastern empire retained some primacy over its western counterpart.[67] In the Ottoman Empire itself, the idea that the sultan was a universal ruler lingered on despite his recognition of the Holy Roman emperor as an equal. Writing in 1798, the Greek Orthodox patriarch of Jerusalem, Anthemus, saw the Ottoman Empire as imposed by God himself as the supreme empire on Earth and something which had arisen due to the dealings of the Palaiologan emperors with the western Christians:[68]

Behold how our merciful and omniscient Lord has managed to preserve the integrity of our holy Orthodox faith and to save (us) all; he brought forth out of nothing the powerful Empire of the Ottomans, which he set up in the place of our Empire of the Romaioi, which had begun in some ways to deviate from the path of the Orthodox faith; and he raised this Empire of the Ottomans above every other in order to prove beyond doubt that it came into being by the will of God .... For there is no authority except that deriving from God.

The Holy Roman idea that the empire located primarily in Germany constituted the only legitimate empire eventually gave rise to the association with Germany and the imperial title, rather than associating it with the ancient Romans. The earliest mention of "the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation" (a phrase rarely used officially) is from the 15th century and its later increasingly used shorthand, imperium Romano-Germanicum, demonstrates that contemporaries of the empire increasingly saw the empire and its emperors not as successors of a Roman Empire that had existed since Antiquity but instead as a new entity that appeared in medieval Germany whose rulers were referred to as "emperors" for political and historical reasons. In the 16th century up to modern times, the term "emperor" was thus also increasingly applied to rulers of other countries.[13] The Holy Roman emperors themselves maintained that they were the successors of the ancient Roman emperors up until the abdication of Francis II, the final Holy Roman emperor, in 1806.[70]

Holy Roman–Russian dispute

By the time of the first embassy from the Holy Roman Empire to Russia in 1488, "the two-emperor problem had [already] translated to Moscow."[71] In 1472, Ivan III, Grand Prince of Moscow, married the niece of the last Byzantine emperor, Zoe Palaiologina, and informally declared himself tsar (emperor) of all the Russian principalities. In 1480, he stopped paying tribute to the Golden Horde and adopted the imperial double-headed eagle as one of his symbols. A distinct Russian theory of translatio imperii was developed by Abbot Philotheus of Pskov. In this doctrine, the first Rome fell to heresy (Catholicism) and the second Rome (Constantinople) to the infidel (Ottomans), but the third Rome (Moscow) would endure until the end of the world.[72]

In 1488, Ivan III demanded recognition of his title as the equivalent of emperor, but this was refused by the Holy Roman emperor Frederick III and other western European rulers. Ivan IV went even further in his imperial claims. He claimed to be a descendant of the first Roman emperor, Augustus, and at his coronation as Tsar in 1561 he used a Slavic translation of the Byzantine coronation service and what he claimed was Byzantine regalia.[72]

According to Marshall Poe, the Third Rome theory first spread among clerics, and for much of its early history still regarded Moscow subordinate to Constantinople (Tsargrad), a position also held by Ivan IV.[73] Poe argues that Philotheus' doctrine of Third Rome may have been mostly forgotten in Russia, relegated to the Old Believers, until shortly before the development of Pan-Slavism. Hence the idea could not have directly influenced the foreign policies of Peter and Catherine, though those Tsars did compare themselves to the Romans. An expansionist version of Third Rome reappeared primarily after the coronation of Alexander II in 1855, a lens through which later Russian writers would re-interpret Early Modern Russia, arguably anachronistically.[74]

Prior to the embassy of Peter the Great in 1697–1698, the tsarist government had a poor understanding of the Holy Roman Empire and its constitution. Under Peter, use of the double-headed eagle increased and other less Byzantine symbols of the Roman past were adopted, as when the tsar was portrayed as an ancient emperor on coins minted after the Battle of Poltava in 1709. The Great Northern War brought Russia into alliance with several north German princes and Russian troops fought in northern Germany. In 1718, Peter published a letter sent to Tsar Vasily III by the Holy Roman emperor Maximilian I dated 4 August 1514[75] in which the emperor addressed the Russian as Kaiser and implicitly his equal. In October 1721, he took the title imperator. The Holy Roman emperors refused to recognise this new title; it was pointed out that the letter from Maximilian was the only example of using the "Kaiser" title for Russian monarchs. Peter's proposal that the Russian and German monarchs alternate as premier rulers in Europe was also rejected. The Emperor Charles VI, supported by France, insisted that there could only be one emperor.[72] Despite the alliance between Charles VI and Catherine I of Russia formally concluded in 1726, it was specifically stipulated that Russian monarch was not to use the imperial title in correspondence with the Holy Roman Emperor,[76] and the alliance treaty omits any references thereto.[77]

The reason for gradual acceptance of the Russian claims was the War of the Austrian Succession, where both sides attempted to draw Russia towards them. In 1742, the Vienna court of Maria Theresa formally recognized the Russian imperial title, though without admitting the Russian ruler's parity. Her rival, the Emperor Charles VII, upon his coronation in 1742 initially refused to acknowledge Russian pretensions. However, by the end of 1743 the course of the war and the influence of Prussian allies (which had recognized Russian imperial title almost immediately in 1721) convinced him that some form of recognition had to be offered. This was done in early 1744; however, in this case Charles VII only acted in his capacity as a Bavarian elector and not as a Holy Roman Emperor.[78] By the time of his death, the issue still had not been formally settled at the imperial level. It was only in 1745 that the imperial electoral college acknowledged Russian claims, which were then confirmed in the document produced by the newly elected emperor Francis I (Maria Theresa's husband) and formally ratified by the Reichstag in 1746. [79][80][81]

Three times between 1733 and 1762 Russian troops fought alongside Austrians inside the empire. The ruler of Russia from 1762 until 1796, Catherine the Great, was a German princess. In 1779 she helped broker the Peace of Teschen that ended the War of the Bavarian Succession. Thereafter, Russia claimed to be a guarantor of the imperial constitution as per the Peace of Westphalia (1648) with the same standing as France and Sweden.[72] In 1780, Catherine II called for the invasion of the Ottoman Empire and the creation of a new Greek Empire or restored Eastern Roman Empire, for which purposes an alliance was made between Joseph II's Holy Roman Empire and Catherine II's Russian Empire.[82] The alliance between Joseph and Catherine was, at the time, heralded as a great success for both parties.[83] Neither the Greek Plan or the Austro-Russian alliance would persist long. Nonetheless, both empires would be part of the anti-Napoleonic Coalitions as well as the Concert of Europe. Any possible Holy Roman–Russian dispute ended with the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806.

Iconography

-

Late Byzantine coat of arms, House of Palaiologos (1400s)

-

Banner of the Holy Roman Empire, House of Habsburg (1400–1806)

-

Coat of arms of Ivan the Terrible, House of Rurik (1577)

-

Coat of arms of the Russian Empire, House of Romanov (1882)

-

Coat of arms of the Austrian Empire, House of Habsburg (1815)

-

The double-headed eagle as used by the Great Seljuk Empire and the Seljuk Sultanate of Rome; used variously by the Ottoman Empire, Ayyubid dynasty, and Mamluk Sultanate

See also

- Legacy of the Roman Empire – for a general overview of the Roman Empire's legacy.

- Succession of the Roman Empire – for claims to being the successor of the Roman or Byzantine Empires.

- Greek East and Latin West – for the division of the Mediterranean into distinct western and eastern linguistic and cultural spheres, dating to the time of the Roman Empire.

- East–West Schism – for the division between Roman and Constantinopolitan patriarchal sees of the Church.

- Caesaropapism – historiographical term for the extensive powers of the Byzantine Emperor in ecclesiastical affairs.

- Investiture Controversy – struggle between the Holy Roman Empire and Papacy for power over ecclesiastical appointments.

- Donation of Constantine – for the papacy's claim to Roman imperial powers over secular affairs and to primacy over the Byzantine See.

- Antipope – for rival claimants to the Roman See, including candidates supported by Byzantine and Holy Roman emperors.

- Precedence among European monarchies

- Consortium imperii – Sharing of Roman imperial authority by two or more emperors

- Emperor at home, king abroad – Similar conflict in the Sinosphere

References

Citations

- ^ The term was introduced in the first major treatise on the issue, by W. Ohnsorge, cf. Ohnsorge 1947.

- ^ a b c Nicol 1967, p. 319.

- ^ Browning 1992, p. 57.

- ^ Browning 1992, p. 58.

- ^ a b Browning 1992, p. 60.

- ^ Frassetto 2003, p. 212.

- ^ a b Nelsen & Guth 2003, p. 4.

- ^ a b Nelsen & Guth 2003, p. 5.

- ^ Van Tricht 2011, p. 73.

- ^ Van Tricht 2011, p. 74.

- ^ Lamers 2015, p. 65.

- ^ a b c d e f Muldoon 1999, p. 47.

- ^ a b c d e Velde 2002.

- ^ Nicol 1967, p. 320.

- ^ a b Browning 1992, p. 61.

- ^ a b c d e f West 2016.

- ^ Muldoon 1999, p. 48.

- ^ a b Muldoon 1999, p. 49.

- ^ a b c Muldoon 1999, p. 50.

- ^ a b Jenkins 1987, p. 285.

- ^ a b Gibbs & Johnson 2002, p. 62.

- ^ Nicol 1967, p. 321.

- ^ a b c Halsall 1996.

- ^ Nicol 1967, p. 318.

- ^ a b Muldoon 1999, p. 51.

- ^ Brand 1968, p. 15.

- ^ Brand 1968, p. 176.

- ^ a b c Brand 1968, p. 177.

- ^ a b Brand 1968, p. 178.

- ^ Brand 1968, p. 179.

- ^ Brand 1968, p. 180.

- ^ Brand 1968, p. 181.

- ^ Loud 2010, p. 79.

- ^ Brand 1968, p. 182.

- ^ Brand 1968, p. 184.

- ^ Brand 1968, p. 185.

- ^ Brand 1968, p. 187.

- ^ Brand 1968, p. 188.

- ^ a b c Van Tricht 2011, p. 64.

- ^ Brand 1968, p. 189.

- ^ Brand 1968, p. 190.

- ^ Brand 1968, p. 191.

- ^ Brand 1968, p. 192.

- ^ Brand 1968, p. 193.

- ^ Brand 1968, p. 194.

- ^ Van Tricht 2011, p. 61.

- ^ Van Tricht 2011, p. 62.

- ^ a b Van Tricht 2011, p. 63.

- ^ Van Tricht 2011, p. 75.

- ^ Van Tricht 2011, p. 76.

- ^ a b Van Tricht 2011, p. 77.

- ^ Geanakoplos 1959, pp. 140f.

- ^ Geanakoplos 1959, pp. 189f.

- ^ Geanakoplos 1959, pp. 258–264.

- ^ Nicol 1967, p. 338.

- ^ Geanakoplos 1959, pp. 264–275.

- ^ Geanakoplos 1959, pp. 286–290.

- ^ Geanakoplos 1959, p. 341.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 194.

- ^ Nicol 1967, p. 332.

- ^ Nicol 1967, p. 316.

- ^ Nicol 1967, p. 333.

- ^ a b Nicol 1967, p. 325.

- ^ a b c Nicol 1967, p. 326.

- ^ Sweeney 1973, pp. 322–324.

- ^ Wilson 2016, p. 148.

- ^ a b c d Süß 2019.

- ^ a b Nicol 1967, p. 334.

- ^ Shaw 1976, p. 94.

- ^ Whaley 2012, pp. 17–20.

- ^ Wilson 2016, p. 153.

- ^ a b c d Wilson 2016, pp. 152–155.

- ^ Poe 1997, pp. 6.

- ^ Poe 1997, pp. 4–7.

- ^ Napier, M. and Browne, J., (eds.) (1842) ‘Czar’, Encyclopædia Britannica, A. and C. Black, p. 579

- ^ Кристиан Штеппан. Австро-русский альянс 1726 г.: долгий процесс при общих политических интересах сторон // Славянский мир в третьем тысячелетии. - Т. 11 (2016). - С. 88.

- ^ Мартенс, Федор Федорович. Recueil des Traités et Conventions conclus par la Russie avec les puissances étrangères, publié d' ordre du Ministère des Affaires Etrangères. — Т. 1: Трактаты с Австрией, 1648—1762. — Санкт-Петербург, 1874. — С. 32—44.

- ^ Richard Lodge. Russia, Prussia, and Great Britain, 1742-4 // The English Historical Review. — Vol. 45 (October 1930). — P. 599.

- ^ Петрова М. А. Признание императорского титула российских государей Священной Римской империей: проблема и пути ее решения (первая половина 1740-х годов) // Новая и новейшая история. — Выпуск 6 (2022). — С. 43—59.

- ^ Петрова М. А. Герман Карл фон Кейзерлинг и признание императорского титула российских государей Священной Римской империей германской нации в 1745–1746 гг. // Вестник МГИМО-Университета. — 2021. — № 14 (6). — С. 89–109.

- ^ Hoffmann 1988, p. 180.

- ^ Beales 1987, pp. 432.

- ^ Beales 1987, p. 285.

Cited bibliography

- Beales, Derek (1987). Joseph II: Volume 1, In the Shadow of Maria Theresa, 1741-1780. New York: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|sfn=ignored (help) - Brand, Charles M. (1968). Byzantium Confronts the West, 1180–1204. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. LCCN 67-20872. OCLC 795121713.

- Browning, Robert (1992). The Byzantine Empire (Revised ed.). CUA Press. ISBN 978-0-8132-0754-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|sfn=ignored (help) - Fine, John V. A. Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

- Frassetto, Michael (2003). Encyclopedia of Barbarian Europe: Society in Transformation. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-263-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|sfn=ignored (help) - Geanakoplos, Deno John (1959). Emperor Michael Palaeologus and the West, 1258–1282: A Study in Byzantine-Latin Relations. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. OCLC 1011763434.

- Gibbs, Marion; Johnson, Sidney (2002). Medieval German Literature: A Companion. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92896-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|sfn=ignored (help) - Hoffmann, Peter (1988). Russland im Zeitalter des Absolutismus (in German). Berlin: Akademie-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-05-000562-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|sfn=ignored (help) - Jenkins, Romilly James Heald (1987). Byzantium: The Imperial Centuries, AD 610-1071. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-8020-6667-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|sfn=ignored (help) - Lamers, Han (2015). Greece Reinvented: Transformations of Byzantine Hellenism in Renaissance Italy. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-29755-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|sfn=ignored (help) - Loud, Graham (2010). The Crusade of Frederick Barbarossa: The History of the Expedition of the Emperor Frederick and Related Texts. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-6575-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|sfn=ignored (help) - Muldoon, James (1999). Empire and Order: The Concept of Empire, 800–1800. Springer. ISBN 978-0-312-22226-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|sfn=ignored (help) - Guth, James L. (2003). "Roman Catholicism and the Founding of Europe: How Catholics Shaped the European Communities". ResearchGate (Draft).

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help); Unknown parameter|ast=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|lsfn=ignored (help) - Nicol, Donald M. (1967). "The Byzantine View of Western Europe" (PDF). Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies. 8 (4): 315–339.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|sfn=ignored (help) - Ohnsorge, Werner (1947). Das Zweikaiserproblem im früheren Mittelalter. Die Bedeutung des byzantinischen Reiches für die Entwicklung der Staatsidee in Europa (in German). Hildesheim: A. Lax. OCLC 302172.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|sfn=ignored (help) - Poe, Marshall (1997). "Moscow, the Third Rome? The Origins and Transformation of a Pivotal Moment" (PDF). The National Council for Soviet and Eastern European Research. 49: 412–429.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|sfn=ignored (help) - Shaw, Stanford (1976). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29163-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|sfn=ignored (help) - Sweeney, James Ross (1973). "Innocent III, Hungary and the Bulgarian Coronation: A Study in Medieval Papal Diplomacy". Church History. 42 (3): 320–334. doi:10.2307/3164389. JSTOR 3164389. S2CID 162901328.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|sfn=ignored (help) - Van Tricht, Filip (2011). "The Imperial Ideology". The Latin Renovatio of Byzantium: The Empire of Constantinople (1204–1228). Leiden: Brill. pp. 61–101. ISBN 978-90-04-20323-5.

- Whaley, Joachim (2012). Germany and the Holy Roman Empire: Volume I: Maximilian I to the Peace of Westphalia, 1493–1648. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968882-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|sfn=ignored (help) - Wilson, Peter H. (2016). Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05809-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|sfn=ignored (help)

Cited web sources

- Halsall, Paul (1996). "Medieval Sourcebook: Liutprand of Cremona: Report of his Mission to Constantinople". Fordham University. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- Süß, Katharina (2019). "Der "Fall" Konstantinopel(s)". kurz!-Geschichte (in German). Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- Velde, François (2002). "The Title of Emperor". Heraldica. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- West, Charles (2016). "Will the real Roman Emperor please stand up?". Turbulent Priests. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

External links

- 2 (number)

- History of the Byzantine Empire

- History of the Ottoman Empire

- International disputes

- Medieval politics

- Naming controversies

- Politics of the Holy Roman Empire

- Former monarchies of Europe

- Rival successions

- Byzantine Empire–Carolingian Empire relations

- Byzantine Empire–Holy Roman Empire relations

- National questions