Safe-cracking

Safe-cracking is the process of opening a safe without either the combination or the key.

Physical methods

Safes have widely different designs, construction methods, and locking mechanisms. A safe cracker needs to know the specifics of whichever will come into play.

Lock manipulation

Lock manipulation is a damage-free, combination-based method. A well known surreptitious bypass technique, it requires knowledge of the device and well developed touch, along with the senses of touch, sight and possibly sound.

While manipulation of combination locks is usually performed on Group 2 locks, many Group 1 locks are also susceptible. The goal is to successfully obtain the combination one number at a time.[1] Manipulation procedures vary, but all rely on exploiting mechanical imperfections in the lock to open it, and, if desired, recover its combination for future use. Similar damage-free bypass can also be achieved by using a computerized auto-dialer or manipulation robot in a so-called brute-force attack. These auto-dialer machines may take 24 hours or more to reach the correct combination,[2] although modern devices with advanced software may do so faster.

Mechanical safe locks are manipulated primarily by feel and vision, with sound sometimes supplementing the process. To find the combination the operator uses the lock against itself by measuring internal movements with the dial numbers. More sophisticated locks use advanced mechanics to reduce any feedback available to a technician in identifying a combination. These group 1 [3] locks were developed in response to group 2[4] lock manipulation.[5] Wheels made from lightweight materials will reduce valuable sensory feedback, but are mainly used for improved resistance against radiographic attacks.[6] Manipulation is often the preferred choice in lost-combination lockouts, since it requires no repairs or damage, but can be time consuming for an operator, the specific difficulty depends on the unique wheel shapes and where the gates rest in relation to them. A novice's opening time will be governed by these random inconsistencies, while some leading champions of this art show consistency. There are also a number of tools on the market to assist safe engineers in manipulating a combination lock open in the field.

Nearly all combination locks allow some "slop" while entering a combination on the dial. On average 1% radial rotation in either direction from the center of the true combination number to allow the fence to fall despite slight deviation, so that for a given safe it may be necessary only to try a subset of the combinations.[7] Such "slops" may allow for a margin of error of plus or minus two digits, which means that trying multiples of five would be sufficient in this case. This drastically reduces the time required to exhaust the number of meaningful combinations. A further reduction in solving time is obtained by trying all possible settings for the last wheel for a given setting of the first wheels before nudging the next-to-last wheel to its next meaningful setting, instead of zeroing the lock each time with a number of turns in one direction.

Guessing the combination

Safes may be compromised surprisingly often by simply guessing the combination. This results from the fact that manufactured safes often come with a manufacturer-set combination. These combinations (known as try-out combinations) are designed to allow owners initial access to the safes so that they may set their own new combinations. Sources exist which list manufacturers' try-out combinations.

Combinations are also unwittingly compromised by the owners of the safes by having the locks set to easy-to-guess combinations such as a birthdate, street address, or driver's license number.

Autodialers

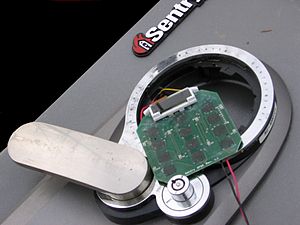

A number of companies and groups have developed autodialing machines to open safes. Unlike fictional machines that can open any combination in a matter of seconds, such machines are usually specific to a particular type of lock and must cycle through thousands of combinations to open a device. An example of such a device is a project completed by two students from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Kyle Vogt and Grant Jordan. Their machine, built to open a Sargent and Greenleaf 8500 lock on a Diebold Safe, found an unknown combination in 21,000 tries. Lockmasters, Inc. markets one autodialing machine [QX3 Combi Autodialer (LKMCOMBI)] that works on a variety of 3 and 4 Wheel combination safe locks.[8]

There also exist computer-aided manipulation tools such as Mas Hamilton's SoftDrill (no longer in production). These tools are similar to autodialers, except they make measurements of the internal components of the lock, and deduce the combination in a similar way to that of a human safe technician.

Weak-point drilling

While some safes are hard to open, some are susceptible to compromise by drilling or other physical methods. Manufacturers publish drill-point diagrams for specific models of safes. These are tightly guarded by both the manufacturers and locksmithing professionals. Drilling is usually aimed at gaining access to the safe by observation or bypass of the locking mechanism. Drilling is the most common method used by locksmiths, and is commonly used in cases of burglary attempts, malfunctioning locks or damaged locks.

In observational attacks, the drill hole allows the safecracker to view the internal state of the combination lock. Drill-points are often located close to the axis of the dial on the combination lock, but observation may sometimes require drilling through the top, sides or rear of the safe. While observing the lock, the locksmith manipulates the dial to align the lock gates so that the fence falls and the bolt is disengaged.

Bypass attacks involve physical manipulation of the bolt mechanism directly, bypassing the combination lock.

All but the simplest safes are designed to protect against drilling attacks through the implementation of hardplate steel (extremely wear-resistant) or composite hardplate (a casting of metal such as cobalt-vanadium alloys with embedded tungsten carbide chips designed to shatter the cutting tips of a drill bit) within the safe, protecting the locking mechanism and other critical areas such as the locking bolts. The use of hardplate ensures that conventional drilling is not successful when used against the safe. Drilling through hardplate requires the use of special-purpose diamond or tungsten-carbide drill-bits. Even then, this can be a time-consuming and difficult process with safes equipped with modern composite hardplates.

Some high-security safes use a glass relocker. This is a piece of tempered glass mounted between the safe door and the combination lock. It has wires attached to the edges. These wires lead to randomly located, spring-loaded bolts. If an attempt is made to penetrate the safe, the penetrating drill or torch could break the glass and release the bolts. These bolts block the retraction of the main locking bolts. To drill a safe with a glass relocker, side, top, or rear drilling may be necessary. A gas abrasive drill can sometimes be used to drill through a glass relocker without triggering it.

Many modern high-security safes also incorporate thermal relockers in conjunction with glass-based relockers (usually a fusible link as part of the relocker cabling), which also activate when the temperature of a safe exceeds a certain level as a defense against torches and thermal lances.

Drilling is an attractive method of safecracking for locksmiths, as it is usually quicker than manipulation, and drilled safes can generally be repaired and returned to service.

Punching, peeling and using a torch are other methods of compromising a safe. The punch system is widely used by criminals for rapid entry. Punching was developed by Pavle Stanimirovic and used in New York City. Peeling is a method that involves removing the outer skin of the safe.

Plasma cutters and thermal lances can be as hot as 2,200 °C (3,990 °F), much hotter than traditional oxyacetylene torches, and can be used to burn through the metal on a safe.

Scoping

Scoping a safe is the process of drilling a hole and inserting a borescope into the safe to get an intimate look into a specific part of the security container. When manipulation proof mechanical locks and glass re-lockers are implemented as security measures, scoping is the most practical option. One common method is called "scoping the change key hole." The safecracker will drill a hole allowing him to get his scope into a position to observe the change key hole. While spinning the dial and looking through the change key hole for certain landmarks on the combination lock's wheel pack, it is possible to obtain the combination and then dial open the safe with the correct combination. This method is common for a professional safe specialist because it leaves the lock in good working order and only simple repairs are needed to bring the safe barrier back to its original condition. It is also a common way to bypass difficult hard plates and glass re-lockers since the change key hole can be scoped by drilling the top, side, or back of the container.

Brute force methods

Other methods of cracking a safe generally involve damaging the safe so that it is no longer functional. These methods may involve explosives or other devices to inflict severe force and damage the safe so it may be opened. Examples of penetration tools include acetylene torches, drills, and thermal lances. This method requires care as the contents of the safe may be damaged. Safe-crackers can use what are known as jam shots to blow off the safe's doors.

Most modern safes are fitted with 'relockers' (like the one described above) which are triggered by excessive force and will then lock the safe semi-permanently (a safe whose relocker has tripped must then be forced, as the combination or key alone will no longer suffice). This is why a professional safe-technician will use manipulation rather than brute force to open a safe so they do not risk releasing the relocker.

Radiological methods

Penetrating radiation such as X-ray radiation can be used to reveal the internal angular relationship of the wheels gates to the flys mechanism to deduce the combination. Some modern safe locks are made of lightweight materials such as nylon to inhibit this technique, since most safe exteriors are made of much denser metals. The Chubb Manifoil Mk4 combination lock contains a lead shield surrounding part of the lock to defeat such attempts to read its wheels.

Tunneling into bank vaults

Large bank vaults which are often located underground have been compromised by safe-crackers who have tunneled in using digging equipment. This method of safe-cracking has been countered by building patrol-passages around the underground vaults. These patrol-passages allow early detection of any attempts to tunnel into a vault.

Safe bouncing

A number of inexpensive safes sold to households for under $100 use mechanical locking mechanisms that are vulnerable to bouncing. Many cheap safes use a magnetic locking pin to prevent lateral movement of an internal locking bolt, and use a solenoid to move the pin when the correct code is entered. This pin can also be moved by the impact of the safe being dropped or struck while on its side, which allows the safe to be opened.[9][10][11] One security researcher taught his three-year-old son how to open most consumer gun safes. More expensive safes use a gear mechanism that is less susceptible to mechanical attacks.

Magnet risk

Low-end home and hotel safes often utilize a solenoid as the locking device and can often be opened using a powerful rare-earth magnet.

Electronic methods

Electronic locks are not vulnerable to traditional manipulation techniques (except for brute-force entry). These locks are often compromised through power analysis attacks.[12][13] Several tools exist that can automatically retrieve or reset the combination of an electronic lock; notably, the Little Black Box[14] and Phoenix. Tools like these are often connected to wires in the lock that can be accessed without causing damage to the lock or container. Nearly all high-end, consumer-grade electronic locks are vulnerable to some form of electronic attack.

TEMPEST

The combinations for some electronic locks can be retrieved by examining electromagnetic emissions coming from the lock. Because of this, many safe locks used to protect critical infrastructure are tested and certified to resist TEMPEST attacks. These include the Kaba Mas X-10 and S&G 2740B, which are FF-L-2740B compliant.

Spiking the lock

Low-end electronic fire-safes, such as those used in hotels or for home use, are locked with either a small motor or a solenoid. If the wires running to the device (solenoid or motor) can be accessed, the device can be 'spiked' with a voltage from an external source - typically a 9 volt battery - to open the container.

Keypad-based attacks

If an electronic lock accepts user input from a keypad, this process can be observed in order to reveal the combination. Common attacks include:

- Visually observing a user enter the combination (shoulder surfing)

- Hiding a camera in the room which records the user pressing keys

- Examining fingerprints left on the keys

- Placing certain gels, powders, or substances on the keys that can be smudged or transferred between keys when the combination is entered, and observed at a later time.

- Placing a "skimmer" (akin to those used for credit card fraud) behind the keypad to record the digital signals that are sent to the lock body when the combination is entered.

- Examining wear or deformity of buttons which are pressed more often than others

Many of these techniques require the attacker to tamper with the keypad, wait for the unsuspecting user to enter the combination, and return at a later time to retrieve the information. These techniques are sometimes used by members of intelligence or law enforcement agencies, as they are often effective and surreptitious.

High-security keypads

Some keypads are designed to inhibit the aforementioned attacks. This is usually accomplished by restricting the viewing angle of the keypad (either by using a mechanical shroud or special buttons), or randomizing the positions of the buttons each time a combination is entered.

Some keypads use small LED or LCD displays inside of the buttons to allow the number on each button to change. This allows for randomization of the button positions, which is normally performed each time the keypad is powered on. The buttons usually contain a lenticular screen in front of the display, which inhibits off-axis viewing of the numbers.

When properly implemented, these keypads make the "shoulder surfing" attack infeasible, as the combination bears no resemblance to the positions of the keys which are pressed.

While these keypads can be used on safes and vaults, this practice is uncommon.

Media depictions

Movies often depict a safe-cracker determining the combination of a safe lock using his fingers or a sensitive listening device to determine the combination of a rotary combination lock. Other films also depict an elaborate scheme of explosives and other devices to open safes.

Some of the more famous works include:

- A Retrieved Reformation (1909)

- The Asphalt Jungle (1950)

- Rififi (1955)

- The Cracksman (1963)

- You Only Live Twice (1967)

- Who's Minding the Mint? (1967)

- Olsen Gang

- Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969)

- On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969)—Auto-dialer

- The Burglars (1971)

- Cool Breeze (1972)

- Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974)

- No Deposit, No Return (1976)

- Thief (1981)

- Vabank (1981)

- Blood Simple (1984)

- Short Circuit 2 (1988)

- Die Hard (1988)—Drilling, guessing electronic passwords

- Disorganized Crime (1989)

- Breaking In (1989)—Drilling, hammering (a cheap safe), nitroglycerin explosives, torch-cutting (with this method the contents were destroyed), social engineering

- Hudson Hawk (1991)

- Killing Zoe (1994)

- Heat (1995)—Drilling, physical sabotage of external security systems

- Safe Men (1998)

- The Newton Boys (1998)

- Blue Streak (1999)

- Sexy Beast (2000)—Tunneling into a bank vault, and physical destruction of security devices by flooding

- Small Time Crooks (2000)

- Ocean's Eleven (2001)—Social engineering, physical sabotage of security systems

- The Score (2001)—rilling, thermal lance, internal explosion. This method shown at the climax of the film was tested on an episode of MythBusters (see below).

- Panic Room (2002)—Drilling, brute force, physical destruction of electronic security systems

- The Italian Job (2003)

- Bad Santa (2003)

- Brainiac: Science Abuse (2003)—The safe was eventually cracked by a high-explosive round fired using a Challenger 2 Tank. The contents were destroyed.

- The Ladykillers (2004)

- Burn Notice (2007–2013)

- The Bank Job (2008)

- Payday: The Heist (2011)

- Dom Hemingway (2013)

- Payday 2 (2013-2016)

- Battlefield Hardline (2015; video game)—Safe-cracking robot

- Army of Thieves (2021)

Three safecracking methods seen in movies were also tested on the television show MythBusters, with some success.[15][16] While the team was able to blow the door off of a safe by filling the safe with water and detonating an explosive inside it, the contents of the safe were destroyed and filling the safe with water required sealing it from the inside. The safe had also sprung many leaks.

See also

References

- ^ Archived from the original on December 9, 2016

- ^ Archived August 1, 2017

- ^ archived from original June 28, 2017

- ^ archived from original on June 28, 2017

- ^ archived from original on August 9, 2016.

- ^ Archived from the original on June 28, 2017.

- ^ Richard P. Feynman as told to Ralph Leighton; edited by Edward Hutchings (1985). "Surely you're joking, Mr. Feynman!": adventures of a curious character. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-01921-7.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Dialer ITL-2000II" (Press release). Zieh-Fix, Inc. Retrieved 2020-10-12.

- ^ Marc Weber Tobias. "Unsafe Gun Safes Can Be Opened By A Three-Year Old". Forbes.

- ^ "Kids Can Open Gun Safes With Straws and Paper Clips, Researchers Say". WIRED. 27 July 2012.

- ^ How to break into most digital safe's. YouTube. 1 March 2012. Archived from the original on 2021-12-12.

- ^ DEFCONConference (2016-11-10), DEF CON 24 - Plore - Side channel attacks on high security electronic safe locks, archived from the original on 2021-12-12, retrieved 2019-05-18

- ^ EEVblog (2015-07-05), EEVblog #762 - How Secure Are Electronic Safe Locks?, archived from the original on 2021-12-12, retrieved 2019-05-18

- ^ "Lockmasters. Lockmasters Little Black Box; LKM522BATMAG". www.lockmasters.com. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

- ^ "Crimes and Myth-Demeanors 1". Mythbusters. Season 4. Episode 54. July 12, 2006.

- ^ "Crimes and Myth-Demeanors 2". MythBusters. Season 4. Episode 59. August 23, 2006.