Meuse-Rhenish

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

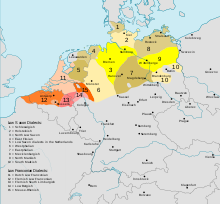

(Low Franconian in yellow)

| This article is a part of a series on |

| Dutch |

|---|

| Low Saxon dialects |

| West Low Franconian dialects |

| East Low Franconian dialects |

In literary studies, Meuse-Rhenish (Template:Lang-de, Template:Lang-nl (rare: Template:Lang-nl), Template:Lang-fr) is the modern term for literature written in the Middle Ages in the greater Meuse-Rhine area, in a literary language that is effectively Middle Dutch. This area stretches in the northern triangle roughly between the rivers Meuse (in Belgium and the Netherlands) and Rhine (in Germany).

It also applies to the Low Franconian dialects that have been spoken in that area continuously from medieval times up to now in modern times in a non-literary context. It includes varieties of South Guelderish (Zuid-Gelders) and Limburgish in the Belgian and Dutch provinces of Limburg, and their German counterparts Low Rhenish (Template:Lang-de) including Bergish in German Northern Rhineland. Although some dialects of this group are spoken within the language area where German is the standard, they actually are Low Franconian in character, and are more closely related to Dutch than to High German, and could therefore also be called Dutch (see also Dutch dialects). With regard to this German part only, Meuse-Rhenish equals the total of Low Rhenish vernaculars.

Low Rhenish and Limburgish

Low Rhenish (Template:Lang-de, Template:Lang-nl) is the collective name in German for the regional Low Franconian language varieties spoken alongside the so-called Lower Rhine in the west of Germany. Low Franconian is a language or dialect group that has developed in the lower parts of the Frankish Empire, northwest of the Benrath line. From this group both the Dutch and later the Afrikaans standard languages have arisen. The differences between Low Rhenish and Low Saxon are smaller than between Low Rhenish and High German. Yet, Low Rhenish does not belong to Low German, but to Low Franconian. Therefore, it could properly be called German Dutch. Indeed, Deutschniederländisch was the official term under the Prussian Reign of the 19th century.

(East Meuse-Rhenish dialect area)

Today, Low Franconian dialects are spoken mainly in regions to the west of the rivers Rhine and IJssel in the Netherlands, in the Dutch speaking part of Belgium, but also in Germany in the Lower Rhine area. Only the latter have traditionally been called Low Rhenish, but they can be regarded as the German extension or counterpart of the Limburgish dialects in the Netherlands and Belgium, and of Zuid-Gelders (South Guelderish) in the Netherlands.

Low Rhenish differs strongly from High German. The more to the north it approaches the Netherlands, the more it sounds like Dutch. As it crosses the Dutch-German as well as the Dutch-Belgian borders, it becomes a part of the language landscape in three neighbouring countries. In two of them Dutch is the standard language. In Germany, important towns on the Lower Rhine and in the Rhine-Ruhr area, including parts of the Düsseldorf Region, are part of it, among them Kleve, Xanten, Wesel, Moers, Essen, Duisburg, Düsseldorf, Oberhausen and Wuppertal. This language area stretches towards the southwest along cities such as Neuss, Krefeld and Mönchengladbach, and the Heinsberg district, where it is called Limburgish, crosses the German-Dutch border into the Dutch province of Limburg, passing cities east of the Meuse river (in both Dutch and German called Maas) such as Venlo, Roermond and Geleen, and then again crosses the Meuse between the Dutch and Belgian provinces of Limburg, encompassing the cities of Maastricht (NL) and Hasselt (B). Thus a mainly political-geographic (not linguistic) division can be made into western (Dutch) South Guelderish and Limburgish at the west side, and eastern (German) Low Rhenish and South East Low Franconian at the east side of the border. The eastmost varieties of the latter, east of the Rhine from Düsseldorf to Wuppertal, are referred to as Bergish.

Limburgish is recognised as a regional language in the Netherlands. As such, it receives moderate protection under chapter 2 of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. The area in which Limburgish is spoken roughly fits within a wide circle from Venlo (NL) to Düsseldorf (D) to Aachen (D) to Maastricht (NL) to Hasselt (B) and back to Venlo.[citation needed] In Germany, it is common to consider the Limburgish varieties as belonging to the Low Franconian language varieties;[citation needed] in the Netherlands and Belgium, however, all these varieties are traditionally considered to be West Central German, part of High German. This difference is caused by a difference in definition: linguists of the Low Countries define a High German variety as one that has taken part in any of the first three phases of the High German consonant shift. In German sources, the dialects linguistically counting as Limburgish spoken east of the river Rhine are often called "Bergish" (after the former Duchy of Berg). West of the river Rhine they are called "Low Rhenish", "Limburgish" or "Ripuarian". Limburgish is not recognised by the German government as an official language. Low Rhenish is considered as a group of dialects in Germany. Together all these varieties belong to a greater continuum; this superordinating group is called Meuse-Rhenish. These insights are rather new among dialectologists on both sides of the national Dutch-German border.[citation needed]

German population in the Meuse-Rhine area are used to let the geographic 'Lower Rhine' area begin approximately with the Benrath line, coincidentally. They do mostly not think of the Ripuarian-speaking area as Low Rhenish, which includes the South Bergish or Upper Bergish area east of the Rhine, south of the Wupper, north of the Sieg.

The Meuse-Rhine triangle

This whole region between the Meuse and the Rhine was linguistically and culturally quite coherent during the so-called Early modern period (1543–1789), though politically more fragmented. The former predominantly Dutch speaking duchies of Guelders and Limburg lay in the heart of this linguistic landscape, but eastward the former duchies of Cleves (entirely), Jülich, and Berg partially, also fit in. The northwestern part of this triangular area came under the influence of the Dutch standard language, especially since the founding of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1815. The southeastern part became a part of the Kingdom of Prussia at the same time, and from then it was subject to High German language domination. At the dialectal level however, mutual understanding is still possible far beyond both sides of the national borders.

The close relation between Limburgish of Belgium and the Netherlands and Bergish is paralleled with that between Zuid-Gelders and Kleverlandish, which are even more clearly belonging to Low Franconian. By including Zuid-Gelders-Kleverlandish-East Bergish in this continuum, we are enlarging the territory and turn the wide circle of Limburgish into a triangle with its top along the line Arnhem – Kleve – Wesel – Duisburg – Wuppertal (along the Rhine-IJssel Line). The Diest- Nijmegen Line is its western border, the Benrath line (from Eupen to Wuppertal) is a major part of the southeastern one.

Within the Dutch speaking area, the Western continuance of Low Rhenish is divided into Limburgish and Zuid-Gelders. Together they belong to the greater triangle-shaped Meuse-Rhine area, a large group of southeastern Low Franconian dialects, including areas in Belgium, the Netherlands and the German Northern Rhineland.

Southeast Limburgish around Aachen

Southeast Limburgish is spoken around Kerkrade, Bocholtz and Vaals in the Netherlands, Aachen[citation needed] in Germany and Raeren and Eynatten in Belgium. In Germany it is mostly considered as a form of Ripuarian, instead of Limburgish. According to a vision, all varieties in a wider half circle some 20 km around Aachen and also the so-called Low Dietsch area between Voeren and Eupen in Belgium, can be taken as a group of its own, at the place where the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany meet.[citation needed] This variety still possesses interesting syntactic idiosyncrasies, probably dating from the period in which the old Duchy of Limburg existed. In Belgium, the south-eastern boundary between Meuse-Rhenish or (French) francique rhéno-mosan and Ripuarian is formed by the Low Dietsch language area. If only tonality is to be taken as to define this variety, it stretches several dozen kilometers into Germany. In Germany, the consensus is to class it as belonging to High German varieties. But this is a little over-simplified. In order to include them properly, a more encompassing concept is needed. The combination of Meuse-Rhenish and Ripuarian, including their overlapping transitional zones of Southeast Limburgish and Low Dietsch, will do.

Classification

- Indo-European

- Germanic

- West Germanic

- Low Franconian

- Meuse-Rhenish

- Limburgish and Zuid-Gelders / Low Rhenish

- Meuse-Rhenish

- Low Franconian

- West Germanic

- Germanic

Sources

- Georg Cornelissen 2003: Kleine niederrheinische Sprachgeschichte (1300–1900) : eine regionale Sprachgeschichte für das deutsch-niederländische Grenzgebiet zwischen Arnheim und Krefeld [with an introduction in Dutch. Geldern / Venray: Stichting Historie Peel-Maas-Niersgebied, ISBN 90-807292-2-1] (in German)

- Michael Elmentaler, Die Schreibsprachgeschichte des Niederrheins. Forschungsprojekt der Uni Duisburg, in: Sprache und Literatur am Niederrhein, Schriftenreihe der Niederrhein-Akademie Bd. 3, 15–34.

- Theodor Frings 1916: Mittelfränkisch-niederfränkische studien I. Das ripuarisch-niederfränkische Übergangsgebiet. II. Zur Geschichte des Niederfränkischenn in: Beiträge zur Geschichte und Sprache der deutschen Literatur 41 (1916), 193–271 en 42, 177–248.

- Irmgard Hantsche 2004: Atlas zur Geschichte des Niederrheins (= Schriftenreihe der Niederrhein-Akademie 4). Bottrop/Essen: Peter Pomp (5e druk). ISBN 3-89355-200-6

- Uwe Ludwig, Thomas Schilp (red.) 2004: Mittelalter an Rhein und Maas. Beiträge zur Geschichte des Niederrheins. Dieter Geuenich zum 60. Geburtstag (= Studien zur Geschichte und Kultur Nordwesteuropas 8). Münster/New York/München/Berlin: Waxmann. ISBN 3-8309-1380-X

- Arend Mihm 1992: Sprache und Geschichte am unteren Niederrhein, in: Jahrbuch des Vereins für niederdeutsche Sprachforschung, 88–122.

- Arend Mihm 2000: Rheinmaasländische Sprachgeschichte von 1500 bis 1650, in: Jürgen Macha, Elmar Neuss, Robert Peters (red.): Rheinisch-Westfälische Sprachgeschichte. Köln enz. (= Niederdeutsche Studien 46), 139–164.

- Helmut Tervooren 2005: Van der Masen tot op den Rijn. Ein Handbuch zur Geschichte der volkssprachlichen mittelalterlichen Literatur im Raum von Rhein und Maas. Geldern: Erich Schmidt. ISBN 3-503-07958-0

See also

- Articles needing cleanup from July 2010

- Cleanup tagged articles without a reason field from July 2010

- Wikipedia pages needing cleanup from July 2010

- West Germanic languages

- Languages of Germany

- German dialects

- Dutch language

- Dutch dialects

- Languages of the Netherlands

- Languages of Belgium

- North Rhine-Westphalia

- Rhineland