Mammalian reproduction

Most mammals are viviparous, giving birth to live young. However, the five species of monotreme, the platypuses and the echidnas, lay eggs. The monotremes have a sex determination system different from that of most other mammals.[1] In particular, the sex chromosomes of a platypus are more like those of a chicken than those of a therian mammal.[2]

The mammary glands of mammals are specialized to produce milk, a liquid used by newborns as their primary source of nutrition. The monotremes branched early from other mammals and do not have the teats seen in most mammals, but they do have mammary glands. The young lick the milk from a mammary patch on the mother's belly.

Viviparous mammals are in the subclass Theria; those living today are in the Marsupialia and Placentalia infraclasses. A marsupial has a short gestation period, typically shorter than its estrous cycle, and gives birth to an underdeveloped (altricial) newborn that then undergoes further development; in many species, this takes place within a pouch-like sac, the marsupium, located in the front of the mother's abdomen. Some placentals, e.g. guinea pig, give birth to fully developed (precocial) young, usually after long gestation periods, while some others, e.g. mouse, give birth to underdeveloped young.

Maturity and reproductive age

Sexual maturity and thus the earliest age at which mammals can reproduce varies dramatically across species. Members of the rodent family Cricetidae can reach sexual maturity in 1–2 months, e.g. the Norway lemming (Lemmus lemmus) in 39 days. Many dogs (family Canidae) and bovids (Bovidae) take about a year to reach maturity while primates (including humans) and dolphins (Delphinidae) require more than 10 years. Some whales take even longer, with the longest duration being recorded for the Bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus), which reaches maturity at an age of only about 23 years.[3]

Reproductive system

Placental mammals

Male placental mammals

The mammalian male reproductive system contains two main divisions, the penis and the testicles, the latter of which is where sperm are produced. In humans, both of these organs are outside the abdominal cavity, but they can be primarily housed within the abdomen in other animals. For instance, a dog's penis is covered by a penile sheath except when mating. Having the testicles outside the abdomen best facilitates temperature regulation of the sperm, which require specific temperatures to survive. The external location may also cause a reduction in the heat-induced contribution to the spontaneous mutation rate in male germinal tissue.[4] Sperm are the smaller of the two gametes and are generally very short-lived, requiring males to produce them continuously from the time of sexual maturity until death. The produced sperm are stored in the epididymis until ejaculation. The sperm cells are motile and they swim using tail-like flagella to propel themselves towards the ovum. The sperm follows temperature gradients (thermotaxis)[5] and chemical gradients (chemotaxis) to locate the ovum.

Female placentals

The mammalian female reproductive system likewise contains two main divisions: the vagina and uterus, which act as the receptacle for the sperm, and the ovaries, which produce the female's ova. All of these parts are always internal. The vagina is attached to the uterus through the cervix, while the uterus is attached to the ovaries via the Fallopian tubes. At certain intervals, the ovaries release an ovum, which passes through the fallopian tube into the uterus.

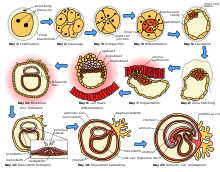

If, in this transit, it meets with sperm, the egg selects sperm with which to merge; this is termed fertilization. The fertilization usually occurs in the oviducts, but can happen in the uterus itself. The zygote then implants itself in the wall of the uterus, where it begins the processes of embryogenesis and morphogenesis. When developed enough to survive outside the womb, the cervix dilates and contractions of the uterus propel the fetus through the birth canal, which is the vagina.

The ova, which are the female sex cells, are much larger than the sperm and are normally formed within the ovaries of the fetus before its birth. They are mostly fixed in location within the ovary until their transit to the uterus, and contain nutrients for the later zygote and embryo. Over a regular interval, in response to hormonal signals, a process of oogenesis matures one ovum which is released and sent down the Fallopian tube. If not fertilized, this egg is released through menstruation in humans and other great apes, and reabsorbed in other mammals in the estrus cycle.

Gestation

Gestation, called pregnancy in humans, is the period of time during which the fetus develops, dividing via mitosis inside the female. During this time, the fetus receives all of its nutrition and oxygenated blood from the female, filtered through the placenta, which is attached to the fetus' abdomen via an umbilical cord. This drain of nutrients can be quite taxing on the female, who is required to ingest slightly higher levels of calories. In addition, certain vitamins and other nutrients are required in greater quantities than normal, often creating abnormal eating habits. The length of gestation, called the gestation period, varies greatly from species to species; it is 40 weeks in humans, 56–60 in giraffes and 16 days in hamsters.

Birth

Once the fetus is sufficiently developing, chemical signals start the process of birth, which begins with contractions of the uterus and the dilation of the cervix. The fetus then descends to the cervix, where it is pushed out into the vagina, and eventually out of the female. The newborn, which is called an infant in humans, should typically begin respiration on its own shortly after birth. Not long after, the placenta is passed as well.

Monotremes

Monotremes, only five species of which exist, all from Australia and New Guinea, are mammals that lay eggs. They have one opening for excretion and reproduction called the cloaca. They hold the eggs internally for several weeks, providing nutrients, and then lay them and cover them like birds. Like marsupial "joeys", monotreme "puggles" are larval and fetus-like,[6] as like them they cannot expand their torso due to the presence of epipubic bones, forcing them to produce undeveloped young.

Marsupials

Marsupials' reproductive systems differ markedly from those of placental mammals,[7][8] though it is probably the plesiomorphic condition found in viviparous mammals, including non-placental eutherians.[9] During embryonic development, a choriovitelline placenta forms in all marsupials. In bandicoots, an additional chorioallantoic placenta forms, although it lacks the chorionic villi found in eutherian placentas.

Gametogenesis

Animals, including mammals, produce gametes (sperm and egg) through meiosis in gonads (testicles in males and ovaries in females). Sperm are produced by the process of spermatogenesis and eggs are produced by oogenesis. These processes are outlined in the article gametogenesis. During gametogenesis in mammals many genes encoding proteins that take part in DNA repair mechanisms show enhanced or specialized expression [10] These mechanisms include meiotic homologous recombinational repair and mismatch repair.

Outline of reproduction by species

- Carnivora#Reproductive system

- Reproductive behavior of dolphins

- Rut (mammalian reproduction)

- Marsupial#Reproduction

- Marsh rice rat#Reproduction and life cycle

See also

- Mammal reproductive system

- Evolution of descended testes in mammals

- Sexual reproduction#Mammals

- Sex organ#Mammals

- Human reproduction

- Animal sexual behavior#Mammals

- Pregnancy (mammals)

- Equine reproductive system

- Carnivora#Reproductive system

- Canine reproduction

- Dolphin#Reproduction and sexuality

- Llama#Reproduction

- Domestic sheep reproduction

References

- ^ Wallis MC, Waters PD, Delbridge ML, Kirby PJ, Pask AJ, Grützner F, Rens W, Ferguson-Smith MA, Graves JA, et al. (2007). "Sex determination in platypus and echidna: autosomal location of SOX3 confirms the absence of SRY from monotremes". Chromosome Research. 15 (8): 949–959. doi:10.1007/s10577-007-1185-3. PMID 18185981. S2CID 812974.

- ^ Marshall Graves, Jennifer A. (2008). "Weird Animal Genomes and the Evolution of Vertebrate Sex and Sex Chromosomes" (PDF). Annual Review of Genetics. 42: 568–586. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091714. PMID 18983263. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-04.

- ^ Pacifici, Michela; Santini, Luca; Marco, Moreno Di; Baisero, Daniele; Francucci, Lucilla; Marasini, Gabriele Grottolo; Visconti, Piero; Rondinini, Carlo (2013-11-13). "Generation length for mammals". Nature Conservation. 5: 89–94. doi:10.3897/natureconservation.5.5734. ISSN 1314-3301.

- ^ Baltz, RH; Bingham, PM; Drake, JW (1976). "Heat mutagenesis in bacteriophage T4: The transition pathway". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 73 (4): 1269–73. Bibcode:1976PNAS...73.1269B. doi:10.1073/pnas.73.4.1269. PMC 430244. PMID 4797.

- ^ Bahat, Anat; Tur-Kaspa, Ilan; Gakamsky, Anna; Giojalas, Laura C.; Breitbart, Haim; Eisenbach, Michael (2003). "Thermotaxis of mammalian sperm cells: A potential navigation mechanism in the female genital tract". Nature Medicine. 9 (2): 149–50. doi:10.1038/nm0203-149. PMID 12563318. S2CID 36538049.

- "Sperm Use Heat Sensors To Find The Egg; Weizmann Institute Research Contributes To Understanding Of Human Fertilization". ScienceDaily (Press release). 3 February 2003.

- ^ Manger, Paul R.; Hall, Leslie S.; Pettigrew, John D. (1998). "The development of the external features of the platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus)". Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences (The Royal Society). 353 (1372): 1115–1125. doi:10.1098/rstb.1998.0270. PMC 1692310. PMID 9720109.

- ^ Australian Mammal Society (December 1978). Australian Mammal Society. Australian Mammal Society.

- ^ Iowa State University Biology Dept. Discoveries about Marsupial Reproduction Anna King 2001. webpage Archived 2012-09-05 at the Wayback Machine (note shows code, html extension omitted)

- ^ Giallombardo, Andres, 2009 New Cretaceous mammals from Mongolia and the early diversification of Eutheria Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, 2009402 pages; AAT 3373736 (abstract) The origin of Placental Mammals, Cimolestidae, Zalambdalestidae

- ^ Baarends WM, van der Laan R, Grootegoed JA (2001). "DNA repair mechanisms and gametogenesis". Reproduction. 121 (1): 31–9. doi:10.1530/reprod/121.1.31. PMID 11226027.