Ramla

Ramla

| |

|---|---|

| Hebrew transcription(s) | |

| • ISO 259 | Ramla |

| • Also spelled | Ramle Ramleh (unofficial) |

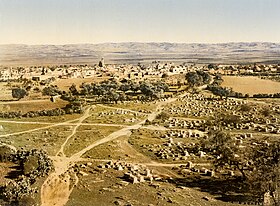

Ramla seen from the White Tower with the eastern hills around Modi'in in the background, 2013 | |

| Coordinates: 31°55′39″N 34°51′45″E / 31.92750°N 34.86250°E | |

| Country | |

| District | Central |

| Subdistrict | Ramla Subdistrict |

| Founded | c. 705–715 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Michael Vidal |

| Area | |

• Total | 9,993 dunams (9.993 km2 or 3.858 sq mi) |

| Population (2022)[1] | |

• Total | 79,132 |

| • Density | 7,900/km2 (21,000/sq mi) |

Ramla or Ramle (Template:Lang-he, Ramlā; Template:Lang-ar, ar-Ramleh)[2] is a city in the Central District of Israel. Today, Ramle is one of Israel's mixed cities, with both a significant Jewish and Arab populations.[3]

The city was founded in the early 8th century CE by the Umayyad prince Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik as the capital of Jund Filastin, the district he governed in Bilad al-Sham before becoming caliph in 715. The city's strategic and economic value derived from its location at the intersection of the Via Maris, connecting Cairo with Damascus, and the road connecting the Mediterranean port of Jaffa with Jerusalem.[4] It rapidly overshadowed the adjacent city of Lydda, whose inhabitants were relocated to the new city. Not long after its establishment, Ramla developed as the commercial centre of Palestine, serving as a hub for pottery, dyeing, weaving, and olive oil, and as the home of numerous Muslim scholars. Its prosperity was lauded by geographers in the 10th–11th centuries, when the city was ruled by the Fatimids and Seljuks.

It lost its role as a provincial capital shortly before the arrival of the First Crusaders (c. 1099), after which it became the scene of various battles between the Crusaders and Fatimids in the first years of the 12th century. Later that century, it became the centre of a lordship in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, a Crusader state established by Godfrey of Bouillon.

Ramla had an Arab-majority population before most were expelled or fled during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War.[5] The town was subsequently repopulated by Jewish immigrants. Today, Ramla is one of Israel's mixed cities, with a population 76% Jewish and 24% Arab (see Arab citizens of Israel).[1][3]

History

Early Muslim period

The Umayyad prince and governor of Palestine, Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik, founded Ramla as the seat of his administration,[6][7][8] replacing Lydda, the Muslims' original provincial capital.[6][7] Sulayman had been appointed governor by his father Caliph Abd al-Malik before the end of his reign in 705 and continued in office through the reign of his brother Caliph al-Walid I (r. 705–715), whom he succeeded.[6] He died as caliph in 717. Ramla remained the capital of Palestine through the Fatimid period (10th–11th centuries).[9] Its role as the principal city and district capital came to an end shortly before the arrival of the First Crusaders in 1099.[10] It received its name, the singular form of raml (sand), from the sandy area in which it sat.[11]

Sulayman's motives for founding Ramla were personal ambition and practical considerations. The location of Ramla near Lydda, a long-established and prosperous city, was logistically and economically advantageous.[12] The area's economic importance was based on its strategic location at the intersection of the two major roads linking Egypt with Syria (the so-called "Via Maris") and linking Jerusalem with the Mediterranean coast.[13] Sulayman established his city in Lydda's vicinity, avoiding Lydda proper. This was likely due to a lack of available space for wide-scale development and agreements dating to the Muslim conquest in the 630s that, at least formally, precluded him from confiscating desirable property within Lydda.[12]

In a tradition recorded by the historian Ibn Fadlallah al-Umari (died 1347), a determined local Christian cleric refused Sulayman's requests for plots in the middle of Lydda. Infuriated, he attempted to have the cleric executed, but his local adviser Raja ibn Haywa dissuaded him and instead proposed building a new city at a superior, adjacent site.[14] In choosing the site, Sulayman utilized the strategic advantages of Lydda's vicinity while avoiding the physical constraints of an already-established urban center.[15] Historian Moshe Sharon holds that Lydda was "too Christian in ethos for the taste of the Umayyad rulers", particularly following the Arabization and Islamization reforms instituted by Abd al-Malik.[16]

According to al-Jahshiyari (died 942), Sulayman sought a lasting reputation as a great builder following the example of his father and al-Walid, the respective founders of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and the Great Mosque of Damascus. The construction of Ramla was Sulayman's "way to immortality" and "his personal stamp on the landscape of Palestine", according to Luz.[17]

The first structure Sulayman erected in Ramla was his palatial residence,[15] which dually served as the seat of Palestine's administration (diwan). The next structure was the Dar al-Sabbaghin (House of the Dyers). At the center of the new city was a congregational mosque, later known as the White Mosque.[18] It was not completed until the reign of Sulayman's successor Caliph Umar II (r. 717–720).[19] The Sulayman's construction works were financially managed by a Christian from Lydda, Bitrik ibn al-Naka.[11] The remains of the White Mosque, dominated by a minaret added at a later date, are visible in the present day. In the courtyard are underground water cisterns from the Umayyad period.[20] From early on, Ramla developed economically as a market town for the surrounding area's agricultural products, and as a center for dyeing, weaving and pottery. It was also home to many Muslim religious scholars.[21]

Sulayman built an aqueduct in the city called al-Barada, which transported water to Ramla from Tel Gezer, about 10 kilometers (6 mi) to the southeast.[22] Ramla superseded Lydda as the commercial center of Palestine. Many of Lydda's Christian, Samaritan and Jewish inhabitants were moved to the new city.[23] Although the traditional accounts are in agreement that Lydda almost immediately fell into obscurity following the founding of Ramla, narratives vary about the extent of Sulayman's efforts to transfer Lydda's inhabitants to Ramla, some holding that he only demolished a church in Lydda and others that he demolished the city altogether.[7] Al-Ya'qubi (died 839) noted Sulayman razed the houses of Lydda's inhabitants to force their relocation to Ramla and punished those who resisted.[24][25] In the words of al-Jahshiyari, Sulayman "founded the town of al-Ramla and its mosque and thus caused the ruin of Lod [Lydda]".[26]

The Abbasids toppled the Umayyads in 750, confiscating the White Mosque and all other Umayyad properties in Ramla. The Abbasids annually reviewed the high costs of maintaining the Barada canal, though starting under the reign of Caliph al-Mu'tasim it became a regular part of the state's expenditures. In the late 9th century the Muslim inhabitants were composed mainly of Arabs and Persians, while the clients of the Muslims were Samaritans.[11]

The golden age of Ramla under the Umayyads and Abbasids, when the city overtook Jerusalem as a trade center, later gave way to a period of political instability and war beginning in the late 10th century. The Egypt-based Fatimids conquered Ramla in 969 and ten years later the city was destroyed by the Jarrahids, a branch of the Tayy tribe.[27]

Nonetheless, the 10th-century Jerusalemite geographer al-Muqaddasi described Ramla as "a fine city, and well built; its water is good and plentiful; it fruits are abundant". He noted that it "combines manifold advantages, situated as it is in the midst of beautiful villages and lordly towns, near to holy places and pleasant hamlets", as well as bountiful fields, walled towns and hospices. The geographer further noted the city's significant commerce and "excellent markets", lauding the quality of its fruits and bread as the best of their kind.[28][29] During this period, Ramla was one of the major centers for the production and export of oil extracted from unripe olives, known as anfa kinon (Greek: ὀμφάκιον, ὀμφάχινον; Latin: omphacium; Template:Lang-ar), and used in cuisine and medicine.[30][31]

Conversely, the city's disadvantages included the severe muddiness of the place during the rainy winter season and its hard, sandy grounds due to its distance from natural water sources. The limited drinking water gathered in the city's cisterns were generally inaccessible to the poorer inhabitants.[32]

By 1011–1012, the Jarrahids controlled all of Palestine, except for the coastal towns, and captured Ramla from its Fatimid garrison, making it their capital. The city and the surrounding places were plundered by the Bedouin, impoverishing much of the population. The Jarrahids brought the Alid emir of Mecca, al-Hasan ibn Ja'far, to act as caliph in defiance of the Fatimids.[33] The development was short-lived, as the Jarrahids abandoned al-Hasan after Fatimid bribes, and the caliphal claimant left the city for Mecca.[34] A Fatimid army led by Ali ibn Ja'far ibn Fallah wrested control of Ramla from the Jarrahids, who continued to dominate the surrounding countryside.[35] The following decade was marked by peace, but, in 1024, the Jarrahids renewed their rebellion. The Fatimid general Anushtakin al-Dizbari secured Ramla for a few months, but the Jarrahids overran the city that year, killing and harassing several inhabitants and seizing much of the population's wealth. They appointed their own governor, Nasr Allah ibn Nizal. In the following year, al-Dizbari drove the Jarrahids out of Ramla, but was recalled to Egypt in 1026. In 1029, he returned and routed the Jarrahids and their Bedouin allies.[36]

Persian geographer Nasir-i-Khusrau visited the city in 1047, remarking:

Ramla is a great city, with strong walls built of stone, mortared, of great height and thickness, with iron gates opening therein. From the town to the sea-coast is a distance of three leagues. The inhabitants get their water from the rainfall, and in each house is a tank for storing the same, in order that there may always be a supply. In the middle of the Friday Mosque [White Mosque], also, is a large tank: and from it, when it is filled with water, anyone who wishes may take. The area of the mosque measures two hundred paces (Gam) by three hundred. Over one of its porches (suffah) is an inscription stating that on the 15th of Muharram, of the year 425 (=10th of December, 1033 CE), there came an earthquake[37] of great violence, which threw down a large number of buildings, but that no single person sustained an injury. In the city of Ramla there is marble in plenty, and most of the buildings and private houses are of this material; and, further, the surface thereof they do most beautifully sculpture and ornament. They cut the marble here with a toothless saw, which is worked with 'Mekka sand'. They saw the marble in length, as is the case with wood, to form the columns; not in across; they also cut it into slabs. The marbles that I saw here were of all colours, some variegated, some green, red, black and white. There is, too, at Ramla, a particular kind of fig, and this they export to all the countries round. This city Ramla, throughout Syria and the West, is known under the name of Filastin.[38][39]

Crusader period

The armies of the First Crusade took the hastily evacuated town without a fight. In the early years of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem though, control over this strategic location led to three consecutive battles between the Crusaders and Egyptian armies from Ascalon, a Fatimid-held town along the southern coast of Palestine. As Crusader rule stabilized, Ramla became the seat of a seigneury in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the Lordship of Ramla within the County of Jaffa and Ascalon. It was a city of some economic significance and an important way station for pilgrims travelling to Jerusalem. The Crusaders identified it with the biblical Ramathaim and called it Arimathea.[40][41]

Around 1163, the rabbi and traveller Benjamin of Tudela, who also mistook it for a more ancient city, visited "Rama, or Ramleh, where there are remains of the walls from the days of our ancestors, for thus it was found written upon the stones. About 300 Jews dwell there. It was formerly a very great city; at a distance of two miles (3 km) there is a large Jewish cemetery."[42]

Mamluk period

In the 1480s, in the late Mamluk era, Felix Fabri visted Ramla and described (among other things) the hammam there; "built in a wonderous and clever fashion".[43]

Ottoman period

In the early days of the Ottoman period, in 1548, a census was taken recording 528 Muslim families and 82 Christian families living in Ramla.[44][45][46]

On 2 March 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte occupied Ramla during his unsuccessful bid to conquer Palestine, using the Franciscan hospice as his headquarters.[47] The village appeared as 'Ramleh' on the map of Pierre Jacotin compiled during this campaign.[48]

In 1838, Edward Robinson found Ramleh to be a town of about 3000 inhabitants, surrounded by olive-groves and vegetables. It had few streets, and the houses were made of stone and were well-built. There were several mosques in the town.[49]

In 1863, Victor Guérin noted that the Latin (Catholic) population was reduced to two priests and 50 parishioners.[50] In 1869, the population was given as 3,460; 3000 Muslims, 400 Greek Orthodox and 60 Catholics.[51]

In 1882, the Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine noted that there was a bazaar in the town, "but its prosperity has much decayed, and many of the houses are falling into ruins, including the Serai."[52] Expansion began only at the end of the 19th century.[53]

In 1889, 31 Jewish worker families settled in the town, which had no Jewish population at the time.[54]

British Mandate period

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, 'Ramleh' had a population of 7,312 inhabitants; 5,837 Muslims, 1,440 Christians and 35 Jews.[55] The Christians were further noted by denomination: 1,226 Orthodox, 2 Syriac Orthodox (Jacobites), 150 Roman Catholics, 8 Melkite Catholics, 4 Maronite, 15 Armenian, 2 Abyssinian Church and 36 Anglicans.[56]

Less than a decade later, the population had increased nearly 25%; the 1931 census recorded 10,347 people, of whom there were 8,157 Muslims, 5 Jews, 2,194 Christians and 2 Druze, in a total of 2,339 houses.[57]

Ramla was connected to wired electricity (supplied by the Zionist-owned Palestine Electric Company) towards the end of the 1920s. Economist Basim Faris noted this fact as proof of Ramla's higher standard of living than neighbouring Lydda. In Ramla, he wrote, "economic demands triumph over nationalism" while Lydda, "which is ten minutes' walk from Ramleh, is still averse to such a convenience as electric current, and so is not as yet served; perhaps the low standard of living of the poor population prevents the use of the service at the present rates, which cannot compete with petroleum for lighting".[58]

Sheikh Mustafa Khairi was mayor of Ramla from 1920 to 1947.[59]

The 1945/46 survey gives 'Ramle' a population of 15,160, of whom 11,900 were Muslim and 3,260 Christian.[60]

1947–48 war

Ramla was part of the territory allotted to a proposed Arab state under the 1947 UN Partition Plan.[61] However, Ramla's geographic location and its strategic position on the main supply route to Jerusalem made it a point of contention during the 1947–1948 civil war, followed by the internationalised 1948 Arab–Israeli War. A bomb by the Jewish militia group Irgun went off in the Ramla market on 18 February, killing 7 residents and injuring 45.[62][63]

After a number of unsuccessful raids on Ramla, the Israeli army launched Operation Dani. Ramla was captured on 12 July 1948, a few days after the capture of Lydda. The Arab resistance surrendered on July 12,[64] and most of the remaining inhabitants were driven out.[65] A disputed claim, advanced by scholars including Ilan Pappé, characterizes this as ethnic cleansing.[66] After the Israeli capture, some 1,000 Arabs remained in Ramla; more were transferred to the town by the IDF from outlying Arab settlements.[citation needed]

State of Israel

Ramla became a mixed Jewish–Arab town within the state of Israel. Arab homes of those who left in Ramla were given by the Israeli government to Jews, first Holocaust refugees from Europe and then immigrants from Arab and Muslim countries.[67] In February 1949, the Jewish population was over 6,000. Ramla remained economically depressed over the next two decades, although the population steadily mounted, reaching 34,000 by 1972.[67]

A 2013 Israeli police report documented that the Central District ranks fourth among Israel's seven districts in terms of drug-related arrests.[68] Today, five of Israel's prisons are located in Ramla, including the maximum-security Ayalon Prison and the country's only women's prison, called Neve Tirza.[69] In 2015, Ramla had one of Israel's highest crime rates.[70]

Earthquakes

The city suffered severe damage from earthquakes in 1033, 1068, 1070, 1546, and 1927.[71]

Landmarks and notable buildings

White Tower

The Tower of Ramla, also known as the White Tower, was built in the 13th century. It served as the minaret of the White Mosque (al-Masjid al-Abyad) erected by Caliph Suleiman in the 8th century, of which only remnants are to be seen today.[72] The tower is six stories high, with a spiral staircase of 119 steps.[73]

Pool of Arches

The Pool of Arches, also known as St. Helen's Pool and Bīr al-Anezīya, is an underground water cistern built during the reign of the Abbasid caliph Haroun al-Rashid in 789 CE (in the Early Muslim period) to provide Ramla with a steady supply of water.[74] Use of the cistern was apparently discontinued at the beginning of the tenth century (the beginning of the Fatimid period), possibly due to the fact that the main aqueduct to the city went out of use at that time.[75]

Great Mosque

The Crusaders built a cathedral in the first half on the 12th century, converted into a mosque when the Mamluks conquered Ramla in the second half of the 13th century, when they added a round minaret, an entrance from the north, and a mihrab. The Great Mosque of Ramla, also known as the El-Omari Mosque, it is in architectural terms Israel's largest and best-preserved Crusader church.[76]

Franciscan church and hospice

The Hospice of St Nicodemus and St Joseph of Arimathea on Ramla's main boulevard, Herzl Street, is easily recognized by its clock-faced, square tower. It belongs to the Franciscan church. Napoleon used the hospice as his headquarters during his Palestine campaign in 1799.

Ramla Museum

The Ramla Museum is housed in the former municipal headquarters of the British Mandatory authorities. The building, from 1922, incorporates elements of Arab architecture such as arched windows and patterned tiled floors. After 1948, it was the central district office of the Israeli Ministry of Finance. In 2001, the building became a museum documenting the history of Ramla.

Other

The Commonwealth War Cemetery is the largest of its kind in Israel, holding graves of soldiers fallen during both World Wars and the British Mandate period.[citation needed]

The Giv'on immigration detention centre is also located in Ramla.[citation needed]

Archaeology

Identification

A tradition reported by Ishtori Haparchi (1280–1355) and other early Jewish writers is that Ramla was the biblical Gath of the Philistines.[77][78] Initial archaeological claims seemed to indicate that Ramla was not built on the site of an ancient city,[79] although in recent years the ruins of an older city were uncovered to the south of Ramla.[80] Earlier, Benjamin Mazar had proposed that ancient Gath lay at the site of Ras Abu Hamid east of Ramla.[81] Avi-Yonah, however, considered that to be a different Gath, usually now called Gath-Gittaim.[82] This view is also supported by other scholars, those holding that there was, both, a Gath (believed to be Tell es-Safi) and Gath-rimmon or Gittaim (in or near Ramla).[83][84]

Excavation history

Archaeological excavations in Ramla conducted in 1992–1995 unearthed the remains of a dyeing industry (Dar al-Sabbaghin, House of the Dyers) near the White Mosque; hydraulic installations such as pools, subterranean reservoirs and cisterns; and abundant ceramic finds that include glass, coins and jar handles stamped with Arabic inscriptions.[85] Excavations in Ramla continued as late as 2010, led by Eli Haddad, Orit Segal, Vered Eshed, and Ron Toueg, on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA).[86]

In January 2021, archaeologists from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Haifa University announced the discovery of six engraving on 120,000-year-old aurochs bone near the city of Ramla in the open-air Middle Paleolithic site of Nesher Ramla. According to archaeologist Yossi Zaidner, this finding was definitely the oldest in the Levant. Three-dimensional imaging and microscopic analysis were used to examine the bone. The six lines ranged in length from 38 to 42 millimeters.[87][88][89]

Cave with rare ecosystem

In May 2006, a naturally sealed-off underground space now known as Ayyalon Cave was discovered near Ramla, outside Moshav Yad Rambam. The cave sustains an unusual type of ecosystem, based on bacteria that create all the energy they need chemically, from the sulfur compounds they find in the water, with no light or organic food coming in from the surface. A bulldozer working in the Nesher cement quarry on the outskirts of Ramla accidentally broke into the cavern. The finds have been attributed to the cave's isolation, which led to the evolution of a whole food chain of specially developed organisms, including several previously unknown species of invertebrates. With several large halls on different levels, it measures 2,700 metres (8,900 ft) long, making it the third-largest limestone cave in Israel.[90]

One of the finds was an eyeless scorpion, given the name Akrav israchanani honouring the researchers who identified it, Israel Naaman and Hanan Dimentman. All ten specimen of the blind scorpion found in the cave had been dead for several years, possibly because recent overpumping of the groundwater has led the underground lake to shrink, and with it the food supply to dwindle. Seven more species of troglobite crustaceans and springtails were discovered in "Noah's Ark Cave", as the cave has been dubbed by journalists, several of them unknown to science.[91]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1945 | 15,300 | — |

| 1972 | 34,000 | +3.00% |

| 2001 | 62,000 | +2.09% |

| 2004 | 63,462 | +0.78% |

| 2009 | 65,800 | +0.73% |

| 2014 | 72,293 | +1.90% |

According to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), a total of 63,462 people were living in Ramla at the end of 2004. In 2001, the ethnic makeup of the city was 80% Jewish, 20% Arab (16% Muslim Arabs and 4% Christian Arabs).[92] Ramla is the center of Karaite Judaism in Israel.[93]

Most Jews from Karachi, Pakistan, have immigranted to Israel and have resettled in Ramle, where they have built a synagogue named Magen Shalome, after the Magain Shalome Synagogue from Karachi.[94]

Economy

According to CBS data, there were 21,000 salaried workers and 1,700 self-employed persons in Ramla in 2000. The mean monthly wage for a salaried worker was NIS 4,300, with a real increase of 4.4% over the course of 2000. Salaried males had a mean monthly wage of NIS 5,200, with a real increase of 3.3%, compared to NIS 3,300 for women, with a real increase of 6.3%. The average income for self-employed persons was NIS 4,900. A total of 1,100 persons received unemployment benefits, and 5,600 received income supplements.

Nesher Israel Cement Enterprises, Israel's sole producer of cement, maintains its flagship factory in Ramla.[95]

Transportation

Ramla Railway Station provides an hourly service on the Israel Railways Tel Aviv–Jerusalem line. The station is located in north east side of the city and originally opened in April 1891, making it the oldest active railway station in Israel.[96] It was most recently reopened on April 12, 2003 after having been rebuilt in a new location closer to the town's center.

Education

According to CBS, there are 31 schools and 12,000 students in the city. These include 22 elementary schools with a student population of 7,700 and nine high schools with a population of 3,800. In 2001, 47% of Ramla's 12th grade students graduated with a bagrut matriculation certificate. Many of the Jewish schools are run by Jewish orthodox organisations.

The Arabs, both Muslims and Christian, increasingly depend on their own private schools and not Israeli governmental schools. There are currently two Christian schools, such as Terra Santa School, the Greek Orthodox School, and there is one Islamic school in preparations.

The Owpen House in Ramla is a preschool and daycare center for Arab and Jewish children. In the afternoons, Open House runs extracurricular coexistence programs for Jewish, Christian, and Muslim children.[97]

Notable people

Alphabetical list by surname where extant. Traditional, pre-modern Arab names by ism (given name).

- Elias Abuelazam (born 1976), serial killer

- Ron Atias (born 1995), taekwondo athlete who represented Israel at the 2016 Summer Olympics

- Orna Barbivai (born 1962), army general and politician

- Yaqub al-Ghusayn (1899–1948), Arab nationalist leader of the Youth Congress Party

- Amir Hadad (born 1978), tennis player[98]

- Barno Itzhakova (1927–2001), Tajik vocalist, immigrated to Ramla in 1991

- Khayr al-Din al-Ramli, 17th-century Islamic legal scholar

- Moni Moshonov (born 1951), actor and comedian

- Yishai Oliel (born 2000), tennis player

- Khalil al-Wazir (1935–1988), a.k.a. Abu Jihad; Palestinian Arab co-founder of the Fatah organization

Twin towns—sister cities

Ramla is twinned with:

See also

References

- ^ a b "Regional Statistics". Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ Also Ramlah, Remle and historically sometimes Rama.

- ^ a b "עיריית רמלה – אתר האינטרנט". Ramla.muni.il. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- ^ University of Haifa Excavation in Marcus Street, Ramala; Reports and studies of the Recanati Institute for Maritime Studies and Excavations, Haifa 2007

- ^ Pilger, 2011, p. 194

- ^ a b c Eisener 1997, p. 821.

- ^ a b c Bacharach 1996, p. 35.

- ^ Luz 1997, p. 52.

- ^ Taxel 2013, p. 161.

- ^ Le Strange, 1890, page ?

- ^ a b c Honigmann, p. 423.

- ^ a b Luz 1997, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Le Strange, 1890, page ? ; Encyclopedia of Islam, article "al-Ramla".

- ^ Luz 1997, p. 48.

- ^ a b Luz 1997, p. 53.

- ^ Sharon 1986, p. 799.

- ^ Luz 1997, pp. 47, 53–54.

- ^ Luz 1997, pp. 37–38, 41–43.

- ^ Bacharach 1996, pp. 27, 35–36.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Islam, article "al-Ramla"; Myriam Rosen-Ayalon, The first century of Ramla, Arabica, vol 43, 1996, pp. 250–263.

- ^ Luz 1997, pp. 43–45.

- ^ Luz 1997, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Luz 1997, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Gordon et al. 2018, p. 1005.

- ^ Sharon 1986, p. 800.

- ^ Luz 1997, p. 47.

- ^ Petersen, pp. 345–346.

- ^ Mukaddasi, 1886, p. 32

- ^ Le Strange, 1890, p. 304

- ^ Muqaddasi (1906), p. 181

- ^ Amar, et al. (2004), p. 78. Cf. Babylonian Talmud, Menahot 86a, where it says that the olives used to produce the oil had not reached one-third of its natural stage of ripeness, and that it was used principally as a depilatory and to flavor meat.

- ^ Honigmann, p. 424.

- ^ Gil, pp. 381–382.

- ^ Kennedy 2016, p. 286.

- ^ Gil, p. 384.

- ^ Gil, pp. 388–391, 396–397.

- ^ Le Strange adds: "This earthquake is mentioned by the Arab annalists, who state that a third of Ramla was thrown down, the mosque in particular being left a mere heap of ruins. Footnote, p. 21

- ^ Nasir-i-Khusrau, 1997, pp. 21- 22

- ^ Le Strange adds: "Ramlah was the Arab capital of the province Filastin (Palestine), and as such was often referred to under the name of its province. The same applied to Sham (Damascus or Syria), Misr (Cairo or Egypt), and other places. Major Fuller begins his translation (J. R. A. S. vol VI, N.S., p. 142) at this point. Footnote, p. 22

- ^ Encyclopedia of Islam, article "al-Ramla".

- ^ Pringle, 1998, p. 181

- ^ Marcus Nathan Adler (1907). The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 26–27. Adler notes that earlier translations wrote "3" rather than "300", but he considers that incorrect.

- ^ Fabri, 1896, p. 256

- ^ Cohen and Lewis, 1978, pp. 135-144

- ^ From the sources listed above: no Jews in 1525, 1538, 1548, 1592; two in 1852

- ^ Petersen, 2005, p. 95

- ^ "INS Scholarship 1998: Jaffa, 1799". Napoleon-series.org. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ^ Karmon, 1960, p. 171

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, pp. 25-33

- ^ Guérin, 1868, pp. 34-55

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 252

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 253

- ^ Yehoshua Ben-Arieh, "The Population of the Large Towns in Palestine During the First Eighty Years of the Nineteenth Century, According to Western Sources", in Studies on Palestine during the Ottoman Period, ed. Moshe Ma'oz (Jerusalem, 1975), pp. 49–69.

- ^ "a באה"ק. המולוניא החדשה רמלה. | המליץ | 26 נובמבר 1889 | אוסף העיתונות | הספרייה הלאומית". www.nli.org.il. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Ramleh, p. 21

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table XIV, p. 21

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 22

- ^ Faris, A. Basim (1936) Electric Power in Syria and Palestine. Beirut: American University of Beirut Press, pp. 66-67. Also see: Shamir, Ronen (2013) Current Flow: The Electrification of Palestine. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 71, 74

- ^ "Sheikh Mustafa Yousef Ahmad Abdelrazzaq El-Khairi (El-Khayri) The Mayor of Ramla (1920–1947)". Palestineremembered.com. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ^ Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 30

- ^ UN map Archived 2009-01-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Embassy of Israel, London, website. 2002. Quoting Zeez Vilani – 'Ramla past and present'.

- ^ Scotsman, 24 February 1948: "'Jerusalem (Monday) – The 'High Command' of the Arab military organisation issued a communiqué to the newspapers here to-day claiming full responsibility for the explosion in Ben Yehuda Street on Sunday. It was said to be in reprisal for an attack by Irgun at Ramleh several days ago.'"

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 427

- ^ Many of the refugees including a large number of children died (at least 400+ according to the Arab historian 'Aref al-Aref) from thirst, hunger, and heat exhaustion after being stripped of their valuables on the way out by Israeli soldiers. Morris, "Operation Dani and the Palestinian Exodus from Lydda and Ramle in 1948", The Middle East Journal, 40 (1986) 82–109; Morris, 2004, pp. 429–430, who quotes the orders; The Rabin Memoirs (censored section, The New York Times, 23 October 1979).

- ^ For the use of the term "ethnic cleansing", see, for example, Pappé 2006.

- On whether what occurred in Lydda and Ramle constituted ethnic cleansing:

- Morris 2008, p. 408: "although an atmosphere of what would later be called ethnic cleansing prevailed during critical months, transfer never became a general or declared Zionist policy. Thus, by war's end, even though much of the country had been 'cleansed' of Arabs, other parts of the country—notably central Galilee—were left with substantial Muslim Arab populations, and towns in the heart of the Jewish coastal strip, Haifa and Jaffa, were left with an Arab minority."

- Spangler 2015, p. 156: "During the Nakba, the 1947 [sic] displacement of Palestinians, Rabin had been second in command over Operation Dani, the ethnic cleansing of the Palestinian towns of towns of Lydda and Ramle."

- Schwartzwald 2012, p. 63: "The facts do not bear out this contention [of ethnic cleansing]. To be sure, some refugees were forced to flee: fifty thousand were expelled from the strategically located towns of Lydda and Ramle ... But these were the exceptions, not the rule, and ethnic cleansing had nothing to do with it."

- Golani and Manna 2011, p. 107: "The expulsion of some 50,000 Palestinians from their homes ... was one of the most visible atrocities stemming from Israel's policy of ethnic cleansing."

- ^ a b A. Golan, Lydda and Ramle: "From Palestinian-Arab to Israeli Towns", 1948–1967, Middle Eastern Studies 39,4 (2003), pp. 121–139.

- ^ "Zachary J. Foster, "Are Lod and Ramla the Drug Capitals of Israel and Palestine?" (Palestine Square Blog)". 30 December 2015. Archived from the original on 30 December 2015.

- ^ "There's only one women's prison in Israel — and a photographer documented the inmates in harrowing detail". Business Insider. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ^ "Police study: Tel Aviv-Jaffa, Haifa, Ramle and Eilat Israel's most violent cities". Ha'aretz. 9 October 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ D. H. K. Amiran (1996). "Location Index for Earthquakes in Israel since 100 B.C.E.". Israel Exploration Journal. 46 (1/2): 120–130.

- ^ Kaplan, Jacob (1993). Stern, Ephraim (ed.). Ramla. Vol. 4. Jerusalem: Carta for the Israel Exploration Society. pp. 1267–1269. Retrieved 23 August 2020 – via Ramle, The White Mosque: The Excavations. At the IAA Gallery of Sites and Finds.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ The Guide to Israel, Zeev Vilnai, Hamakor Press, Jerusalem, 1972, p. 208.

- ^ "Ramla Pool of Arches". Iaa-conservation.org.il. 2005-12-27. Retrieved 2014-02-04.

- ^ Toueg, Ron, Ramla, Pool of the Arches: Final Report (09/07/2020), Hadashot Arkheologiyot, Volume 132, Year 2020, Israel Antiquities Authority. Accessed 27 July 2020.

- ^ Ramla Tourism Sites at the official website Archived 2015-02-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Ishtori Haparchi, Kaphtor u'ferach, vol. II, chapter 11, s.v. ויבנה בארץ פלשתים, (3rd edition) Jerusalem 2007, p. 78 (Hebrew)

- ^ B. Mazar (1954). "Gath and Gittaim". Israel Exploration Journal. 4 (3/4): 227–235.

- ^ Nimrod Luz (1997). "The Construction of an Islamic City in Palestine. The Case of Umayyad al-Ramla". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Third Series. 7 (1): 27–54. doi:10.1017/S1356186300008300. S2CID 163178178.

- ^ "Volume 121 Year 2009 Ramla (South)". www.hadashot-esi.org.il.

- ^ Mazar (Maisler), Benjamin (1954). "Gath and Gittaim". Israel Exploration Journal. 4 (3): 233. JSTOR 27924579.

- ^ Michael Avi-Yonah. "Gath". Encyclopedia Judaica. Vol. 7 (second ed.). p. 395.

- ^ Rainey, Anson (1998). "Review by: Anson F. Rainey". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 118 (1): 73. JSTOR 606301.

- ^ Rainey, Anson (1975). "The Identification of Philistine Gath". Eretz-Israel: Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies. Nelson Glueck Memorial Volume: 63–76. JSTOR 23619091.

- ^ "Vincenz : Ramla | The Shelby White – Leon Levy Program for Archaeological Publications". Fas.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on September 6, 2008. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- ^ Israel Antiquities Authority, Excavators and Excavations Permit for Year 2010, Survey Permit # A-5947, Survey Permit # A-6029, Survey Permit # A-6052, and Survey Permit # A-6057

- ^ staff, T. O. I. "Scientists: Bone carving found in Israel could be earliest human use of symbols". www.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved 2021-07-08.

- ^ Davis-Marks, Isis. "120,000-Year-Old Cattle Bone Carvings May Be World's Oldest Surviving Symbols". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2021-07-08.

- ^ Prévost, Marion; Groman-Yaroslavski, Iris; Crater Gershtein, Kathryn M.; Tejero, José-Miguel; Zaidner, Yossi (2021-01-20). "Early evidence for symbolic behavior in the Levantine Middle Paleolithic: A 120 ka old engraved aurochs bone shaft from the open-air site of Nesher Ramla, Israel". Quaternary International. 624: 80–93. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2021.01.002. ISSN 1040-6182. S2CID 234236699.

- ^ "Underground world found at quarry – Israel Culture, Ynetnews". Ynetnews. Ynetnews.com. June 20, 1995. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- ^ "One year later, 'Noah's Ark' cave is no longer a safe haven". Haaretz. 19 July 2007. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- ^ "Ramla, Israel". Kansas City Sister Cities.

- ^ "Karaite Center". Ramla Tourism Site. Archived from the original on 2015-02-07.

- ^ Pakistan Jewish Virtual History Tour, Jewish Virtual Library

- ^ "Nesher Israel Cement Enterprises Ltd". Nesher.co.il. Archived from the original on 2014-02-22. Retrieved 2014-02-04.

- ^ Jaffa Station History, retrieved November 6, 2009

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Tennis – 2002 – WIMBLEDON – July 1 – Aisam-Ul-Haq Qureshi". ASAP Sports. July 1, 2002. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

Bibliography

- Amar, Z.; Serri, Yaron (2004). The Land of Israel and Syria as Described by al-Tamimi – Jerusalem Physician of the 10th Century (in Hebrew). Ramat-Gan. ISBN 965-226-252-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) -- (OCLC 607157392) - Bacharach, Jere L. (1996). "Marwanid Umayyad Building Activities: Speculations on Patronage". Muqarnas Online. 13: 27–44. doi:10.1163/22118993-90000355. ISSN 2211-8993. JSTOR 1523250.

- Barron, J. B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Cohen, Amnon; Lewis, B. (1978). Population and Revenue in the Towns of Palestine in the Sixteenth Century. ISBN 0783793227.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H. H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Eisener, R. (1997). "Sulaymān b. ʿAbd al-Malik". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume IX: San–Sze. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 821–822. ISBN 978-90-04-10422-8.

- Fabri, F. (1896). Felix Fabri (circa 1480–1483 A.D.) vol I, part I. Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society.

- Gordon, Matthew S.; Robinson, Chase F.; Rowson, Everett K.; Fishbein, Michael (2018). The Works of Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-Yaʿqūbī (Volume 3): An English Translation. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-35621-4.

- Guérin, V. (1868). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Centre.

- Karmon, Y. (1960). "An Analysis of Jacotin's Map of Palestine" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 10 (3, 4): 155–173, 244–253.

- Le Strange, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Luz, Nimrod (April 1997). "The Construction of an Islamic City in Palestine. The Case of Umayyad al-Ramla". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 7 (1): 27–54. doi:10.1017/S1356186300008300. JSTOR 25183294. S2CID 163178178.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Mukaddasi (1886). Description of Syria, including Palestine. London: Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society.

- Mukaddasi (1906). M.J. de Goeje (ed.). Kitāb Aḥsan at-taqāsīm fī maʻrifat al-aqālīm (The Best Divisions for Knowledge of the Regions) (in Arabic). Leiden: Brill Co. OCLC 313566614. (3rd edition printed by Brill in 1967)

- Nasir-i-Khusrau (1897). Le Strange, Guy (ed.). Vol IV. A journey through Syria and Palestine. By Nasir-i-Khusrau [1047 A.D.]. The pilgrimage of Saewulf to Jerusalem. The pilgrimage of the Russian abbot Daniel. Translated by Guy Le Strange. London: Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society.

- Palmer, E. H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Petersen, Andrew (2005). The Towns of Palestine Under Muslim Rule. British Archaeological Reports. ISBN 1841718211.

- Pococke, R. (1745). A description of the East, and some other countries. Vol. 2. London: Printed for the author, by W. Bowyer. (Pococke, 1745, vol 2, p. 4; cited in Robinson and Smith, vol. 3, 1841, p. 233)

- Pilger, J. (2011). Freedom Next Time. Random House. ISBN 978-1407083865.

- Pringle, D. (1998). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: L-Z (excluding Tyre). Vol. II. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39037-0.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Sharon, M. (1986). "Ludd". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume V: Khe–Mahi. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 798–803. ISBN 978-90-04-07819-2.

- Taxel, Itamar (May 2013). "Rural Settlement Processes in Central Palestine, ca. 640–800 C.E.: The Ramla-Yavneh Region as a Case Study". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 369 (369). The American Schools of Oriental Research: 157–199. doi:10.5615/bullamerschoorie.369.0157. JSTOR 10.5615/bullamerschoorie.369.0157. S2CID 163507411.

External links

- Official site (in Hebrew)

- "A Dangerous Tour at Ramle", by Eitan Bronstein

- Portal Ramla

- Israel Service Corps: Ramla Community Involvement

- The Tower of Ramla, 1877

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 13: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Central District (Israel)

- Ramla

- Arab Christian communities in Israel

- Castles and fortifications of the Kingdom of Jerusalem

- Cities in Central District (Israel)

- History of Israel by location

- Populated places established in the 8th century

- Mixed Israeli communities

- 8th-century establishments in the Umayyad Caliphate