Irish Crown Jewels

The Jewels Belonging to the Most Illustrious Order of Saint Patrick, commonly called the Irish Crown Jewels or State Jewels of Ireland, were the heavily jewelled star and badge regalia created in 1831 for the Sovereign and Grand Master of the Order of St Patrick, an order of knighthood established in 1783 by George III as King of Ireland to be an Irish equivalent of the English Order of the Garter and the Scottish Order of the Thistle. The British monarch was the Sovereign of the order, as monarch of Ireland until 1801 and of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland thereafter. The Lord Lieutenant of Ireland was the Grand Master in the absence of the Sovereign. The insignia were worn by the Sovereign at the investiture of new knights as members of the order, and by the Grand Master on other formal ceremonial occasions.

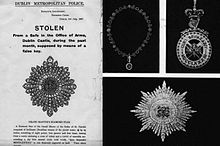

They were stolen from Dublin Castle in 1907, along with the collars of five knights of the order. The theft has never been solved, and the items have never been recovered.[1]

History

The original regalia of the Sovereign were only slightly more opulent than the insignia of an ordinary Knight Member of the order; the king's 1783 ordinance said they were to be "of the same materials and fashion as those of Our Knights, save only those alterations which befit Our dignity".[2] The regalia were replaced in 1831 by new ones presented by William IV as part of a revision of the order's structure. They were delivered from London to Dublin on 15 March by the 18th Earl of Erroll in a mahogany box together with a document titled "A Description of the Jewels of the Order of St. Patrick, made by command of His Majesty King William the Fourth, for the use of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, and which are Crown Jewels."[3] They contained 394 precious stones taken from the English Crown Jewels of Queen Charlotte and the Order of the Bath star of her husband George III.[4] The jewels were assembled by Rundell & Bridge. On the badge of Saint Patrick's blue enamel, the green shamrock was of emeralds and the red Saint Patrick's Saltire of rubies; the motto of the order was in pink diamonds and the encrustation was of Brazilian diamonds of the first water.[4][5] Notices issued after the theft described the jewels thus:

A Diamond Star of the Grand Master of the Order of St. Patrick composed of brilliants (Brazilian stones) of the purest water, 4+5⁄8 by 4+1⁄4 inches, consisting of eight points, four greater and four lesser, issuing from a centre enclosing a cross of rubies and a trefoil of emeralds surrounding a sky blue enamel circle with words, "Quis Separabit MDCCLXXXIII." in rose diamonds engraved on back. Value about £14,000. (equivalent to £1,870,000 in 2023).[6]

— [7]

A Diamond Badge of the Grand Master of the Order of St. Patrick set in silver containing a trefoil in emeralds on a ruby cross surrounded by a sky blue enamelled circle with "Quis Separabit MDCCLXXXIII." in rose diamonds surrounded by a wreath of trefoils in emeralds, the whole enclosed by a circle of large single Brazilian stones of the finest water, surmounted by a crowned harp in diamonds and loop, also in Brazilian stones. Total size of oval 3 by 2+3⁄8 inches; height 5+5⁄8 inches. Value £16,000. (equivalent to £2,140,000 in 2023).[6]

— [8]

When not being worn or cleaned, the insignia of the Sovereign and those of deceased Knights were in the custody of the Ulster King of Arms, the senior Irish officer of arms, and kept in a bank vault.[9] The description "Crown Jewels" was officially applied to the star and badge regalia of the Sovereign in a 1905 revision of the order's statutes. The label "Irish Crown Jewels" was publicised by newspapers after their theft.[10]

Theft

In 1903, the Office of Arms, the Ulster King of Arms's office within the Dublin Castle complex, was transferred from the Bermingham Tower to the Bedford or Clock Tower. The jewels were transferred to a new safe, which was to be placed in the newly constructed strongroom. The new safe was too large for the doorway to the strongroom, and Sir Arthur Vicars, the Ulster King of Arms, instead had it placed in his library.[1] Seven latch keys to the door of the Office of Arms were held by Vicars and his staff, and two keys to the safe containing the regalia were both in the custody of Vicars. Vicars was known to get drunk on overnight duty and he once awoke to find the jewels around his neck. It is not known whether this was a prank or practice for the actual theft.

The regalia were last worn by the Lord Lieutenant, The 7th Earl of Aberdeen, on 15 March 1907, at a function to mark Saint Patrick's Day on 17 March. They were last known to be in the safe on 11 June, when Vicars showed them to a visitor to his office. The jewels were discovered to be missing on 6 July 1907, four days before the start of a visit by King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra to the Irish International Exhibition, at which it was planned to invest The 2nd Baron Castletown into the order. The theft is reported to have angered the King, but the visit went ahead.[11] However, the investiture ceremony was cancelled.[9] Some family jewels inherited by Vicars and valued at £1,500 (equivalent to £200,000 in 2023)[6] were also stolen,[12] along with the collars of five Knight Members of the order: four living (the Marquess of Ormonde and Earls of Howth, of Enniskillen, and of Mayo) and one deceased (The 9th Earl of Cork).[13] These were valued at £1,050 (equivalent to £140,000 in 2023)[6].[14]

Investigation

A police investigation was conducted by the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP).[13] Posters issued by the DMP depicted and described the missing jewels. Detective Chief Inspector John Kane of Scotland Yard arrived on 12 July to assist.[5] His report, never released, is said to have named the culprit and to have been suppressed by the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC).[5] Vicars refused to resign his position, and similarly refused to appear at a Viceregal Commission under Judge James Johnston Shaw into the theft held from 10 January 1908. Vicars argued for a public Royal Commission instead, which would have had power to subpoena witnesses.[1] He publicly accused his second in command, Francis Shackleton, of the theft. Kane explicitly denied to the Commission that Shackleton, brother of the explorer Ernest Shackleton, was involved. Shackleton was exonerated in the Commission's report, and Vicars was found to have "not exercise[d] due vigilance or proper care as the custodian of the regalia." Vicars was compelled to resign, as were all the staff in his personal employ.

Rumours and theories

There was a theory that the jewels were stolen by political activists who were in the Irish Republican Brotherhood. In the House of Commons in August 1907, Pat O'Brien, MP blamed "loyal and patriotic Unionist criminals".[15] Lord Haddo, the son of the Lord Lieutenant, was alleged by some newspapers to have been involved in the theft;[16] Augustine Birrell, the Chief Secretary for Ireland, stated in the Commons that Haddo had been in Great Britain throughout the time period within which the theft took place.[17] In 1912 and 1913 Laurence Ginnell suggested that the police investigation had established the identity of the thief, that his report had been suppressed to avoid scandal,[18] and that the jewels were "at present within the reach of the Irish Government awaiting the invention of some plausible method of restoring them without getting entangled in the Criminal Law".[19] In an adjournment debate in 1912 he alleged:[20]

- The police charged with collecting evidence in connection with the disappearance of the Crown Jewels from Dublin Castle in 1907 collected evidence inseparable from it of criminal debauchery and sodomy being committed in the castle by officials, Army officers, and a couple of nondescripts of such position that their conviction and exposure would have led to an upheaval from which the Chief Secretary shrank. To prevent that, he suspended the operation of the Criminal Law, and appointed a whitewashing commission with the result for which it was appointed.

His speech was curtailed when a quorum of forty MPs was not present in the chamber.[20] He elaborated the following week on the alleged depravity of "two of the characters", namely army captain Richard Gorges ("a reckless bully, a robber, a murderer, a bugger, and a sod") and Shackleton ("One of [Gorges'] chums in the Castle, and a participant in the debauchery").[21] Birrell denied any cover-up and urged Ginnell to give to the police any evidence he had relating to the theft or any sexual crime.[21] Walter Vavasour Faber also asked about a cover-up;[22] Edward Legge supported this theory.[23]

After Francis Shackleton was imprisoned in 1914 for passing a cheque stolen from a widow,[9][24] The 6th Earl Winterton asked for the judicial inquiry demanded by Vicars.[25]

On 23 November 1912, the London Mail alleged that Vicars had allowed a woman reported to be his mistress to obtain a copy to the key to the safe and that she had fled to Paris with the jewels. In July 1913 Vicars sued the paper for libel; it admitted that the story was completely baseless and that the woman in question did not exist; Vicars was awarded damages of £5,000.[26] Vicars left nothing in his will to his half-brother Pierce Charles de Lacy O'Mahony, on the grounds that Mahony had repudiated a promise to recompense Vicars for the loss of income caused by his resignation.[27]

Another theory was that the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) had smuggled the jewels to the United States.[4]

A 1927 memo of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State, released in the 1970s, stated that W. T. Cosgrave "understands that the Castle jewels are for sale and that they could be got for £2,000 or £3,000."[4]

In 1968 the Irish journalist Bulmer Hobson published an account of the theft[28] which stated that the jewels had been stolen by Shackleton in complicity with Captain Richard Gorges, after they had plied Vicars with so much whiskey that he had passed out. Hobson claimed the jewels had been taken to Amsterdam by Shackleton, and pledged for £20,000, with the proviso that they not be broken up for three years. Both men were homosexual, and official fears that a witch-hunt might cause greater scandal (as had the Dublin Castle homosexual scandals of 1884), may have been a reason for the compromising of the investigation.[29] In 1913 Shackleton was charged with defrauding the Scottish nobleman Lord Ronald Gower of his fortune.[30]

A 2002 book suggests the jewels were stolen as a Unionist plot to embarrass the Liberal government, and later secretly returned to the Royal Family.[31]

Folklore within the Genealogical Office of the Republic of Ireland, the successor to the Office of Arms, was that the jewels were never removed from the Clock Tower, but were merely hidden. In 1983, when the Genealogical Office vacated its structurally unsound premises inside the Clock Tower, Donal Begley, the Chief Herald of Ireland, supervised the removal of walls and floorboards, in case the jewels might be revealed, but they were not.[32]

Fictional accounts

A 1967 book suggests that the 1908 Sherlock Holmes story "The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans" was inspired by the theft; author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was a friend of Vicars, and the fictional Valentine Walters, who steals the Plans but is caught by Holmes, has similarities with Francis Shackleton.[33]

Jewels, a Bob Perrin novel based on the theft, was published in 1977.[34]

The Case of the Crown Jewels by Donald Serrell Thomas, a Sherlock Holmes story based on the theft, was published in 1997.

Notes

- ^ a b c Nosowitz, Dan (4 November 2021). "The Greatest Unsolved Heist in Irish History". Atlas Obscura - Stories. Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ Statutes and Ordinances 1852, pp.46–47

- ^ Statutes and Ordinances 1852, pp.104–105

- ^ a b c d O'Riordan, Tomás (Winter 2001). "The Theft of the Irish Crown Jewels, 1907". History Ireland. 9 (4).

- ^ a b c "The Theft of the Irish 'Crown Jewels'". Online exhibitions. Dublin: National Archives of Ireland. 2007. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ "DMP – poster 1". Dublin Metropolitan Police. 2007 [Original date 8 July 1907]. Archived from the original on 6 February 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ^ "DMP – poster 2". Dublin Metropolitan Police. 2007 [Original date 8 July 1907]. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ^ a b c "Chapter 12: The Illustrious Order of St. Patrick". History of Dublin Castle. Office of Public Works. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ Galloway, Peter (1983). The Most Illustrious Order of St. Patrick: 1783 – 1983. Phillimore. ISBN 9780850335088.

- ^ Legge 1913, p.55

- ^ "The mystery of the missing Crown Jewels". The Irish Times. 26 March 2002. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ a b Superintendent John Lowe's report – page 1 (Report). National Archives of Ireland. CSORP/1913/18119 – page 1. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. With links to subsequent pages.

- ^ "DMP – poster 3". National Archives of Ireland. 2007 [Original date 8 July 1907]. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013.

- ^ HC Deb 13 August 1907 vol 180 cc1065-6

- ^ Legge 1913, pp. xv, 62–63

- ^ HC Deb 01 April 1908 vol 187 cc509-10

- ^ HC Deb 28 January 1913 vol 47 cc1189-90

- ^ HC Deb 23 January 1913 vol 47 cc589-90

- ^ a b HC Deb 06 December 1912 vol 44 cc2751-2

- ^ a b HC Deb 20 December 1912 vol 45 cc1955-62

- ^ HC Deb 13 February 1913 vol 48 cc1159-61

- ^ Legge 1913, pp. 64–65

- ^ "The Case of Francis Shackleton". Auckland Star. 8 March 1913. p. 13. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ HC Deb 19 February 1914 vol 58 cc1113-4

- ^ "The Irish Crown Jewels". No. Volume XLVII, Issue 20. Marlborough Express. 29 August 1913. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

{{cite news}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ "Will of Sir Arthur Vicars". National Archives of Ireland, Principal Registry. 20 March 1922. p. 4.

- ^ Hobson, Bulmer (1968). Ireland Yesterday and Tomorrow. Tralee.

- ^ Trevelyan, Raleigh (1978). Princes Under The Volcano. William Morrow & Company. pp. 337–8.

- ^ "COLOSSAL FRAUD. LORD RONALD GOWER RUINED. SIR E. SHACKLETON'S BROTHER CHARGED". The West Australian. 15 February 1913. p. 11.

- ^ Cafferky, John; Hannafin, Kevin (2002). Scandal & betrayal: Shackleton and the Irish crown jewels. Collins. ISBN 9781903464250.

- ^ Hood 2002 pp.232–233

- ^ Bamford, Francis; Bankes, Viola (1967). Vicious Circle: The Case of the Missing Irish Crown Jewels. Horizon Press.

- ^ Perrin, Robert (1977). Jewels. Pan Books. ISBN 9780330255875.

References

- Hood, Susan (2002). Royal Roots, Republican Inheritance: The Survival of the Office of Arms. Dublin: Woodfield Press in association with National Library of Ireland. ISBN 9780953429332.

- Statutes and Ordinances of the Most Illustrious Order of St. Patrick. Dublin: George & John Grierson for Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1852. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- Legge, Edward (1913). More about King Edward. Boston: Small, Maynard.

- Viceregal Commission to investigate the circumstances of the loss of the regalia of the Order of Saint Patrick (1908). Report. Command papers. Vol. Cd.3906. HMSO. Retrieved 31 October 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- {{cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/op1255338-1001 |title=Appendix |series=Command papers |volume=Cd.3936 |access-date=31 October 2019 |via=Internet Archive |date=1908 |author=Viceregal Commission to investigate the circumstances of the loss of the regalia of the Order of Saint Patrick

Further reading

- Peter Galloway, The Most Illustrious Order: The Order of Saint Patrick and its Knights. Unicorn Press, London, 1999. ISBN 0-906290-23-6.

External links

- Murphy, Sean J (29 April 2008). "A Centenary Report on the Theft of the Irish Crown Jewels in 1907". Irish Historical Mysteries. Bray, Co. Wicklow, Ireland: Centre for Irish Genealogical and Historical Studies. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- "The Theft of the Irish 'Crown Jewels'". Online exhibitions. Dublin: National Archives of Ireland. 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2019.