Scorer

Scoring in cricket matches involves two elements – the number of runs scored and the number of wickets lost by each team. The scorer is someone appointed to record all runs scored, all wickets taken and, where appropriate, the number of overs bowled. In professional games, in compliance with the Laws of Cricket, two scorers are appointed, most often one provided by each team.

The scorers have no say in whether runs or extras are scored, wickets taken or overs bowled. This is the job of the umpires on the field of play, who signal to the scorers in cases of ambiguity such as when runs are to be given as extras rather than credited to the batsmen, or when the batsman is to be awarded a boundary 4 or 6. So that the umpire knows that they have seen each signal, the scorers are required to immediately acknowledge it.

While it is possible to keep score using a pencil and plain paper, scorers often use pre-printed scoring books, and these are commercially available in many different styles. Simple score books allow the recording of each batsman's runs, their scores and mode of dismissal, the bowlers' analyses, the team score and the score at the fall of each wicket. More sophisticated score books allow for the recording of more detail, and other statistics such as the number of balls faced by each batsman. Scorers also sometimes produce their own scoring sheets to suit their techniques, and some use coloured pens to highlight events such as wickets, or differentiate the actions of different batsmen or bowlers. It is often possible to tell from a modern scorecard the time at which everything occurred, who bowled each delivery, which batsman faced it, whether the batsman left the ball or played and missed, or which direction the batsman hit the ball and whether runs were scored. Sometimes details of occurrences between deliveries, or incidental details like the weather, are recorded.

In early times runs scored were sometimes simply recorded by carving notches on a stick – this root of the use of the slang term "notches" for "runs". In contrast, scoring in the modern game has become a specialism, particularly for international and national cricket competitions. While the scorers' role is clearly defined under the Laws of Cricket to be merely the recording of runs, wickets and overs, and the constant checking of the accuracy of their records with each other and with the umpires, in practice a modern scorer's role is complicated by other requirements. For instance, cricket authorities often require information about matters such as the rate at which teams bowled their overs. The media also ask to be notified of records, statistics and averages. For many important matches, unofficial scorers keep tally for the broadcast commentators and newspaper journalists allowing the official scorers to concentrate undisturbed. In the English county game, the scorers also keep score on a computer that updates a central server, to meet the demands of the online press that scores should be as up-to-date as possible.

The official scorers occasionally make mistakes, but unlike umpires' mistakes these may be corrected after the event.

Some cricket statisticians who keep score unofficially for the printed and broadcast media have become quite famous, for instance Bill Frindall, who scored for the BBC radio commentary team from 1966 to 2008, and Jo King.

The ECB's Association of Cricket Officials provides training for scorers.[1]

Methods of scoring

There are predominantly two methods that scorers use to record a game: manually and computerised.

The manual method uses a scorecard and a pen. The scorecard is colloquially known as The Book. Using the book, the scorer fills out two main sections per ball, the bowling analysis and the batting analysis. Each section helps track the number of balls bowled in an over, any extras (such as Wide Balls and No Balls) and also any wickets (or dismissals). At the end of each over, the scorer may fill in an over analysis with the score at the end of the over, the number of wickets that have fallen, any penalties incurred and the number of the bowler in the analysis.

Most software used for cricket scoring uses a form at the front end with buttons for the scorer to press to record ball by ball events. Additional functions include being able to draw a line denoting where the ball went from the batting crease and where the ball pitched. This gives additional charts tracking bowling placement and shot selection which can then be used at the coaching level. This additional information, however, does not form part of the critical role of a scorer, which is to keep track of the score of the game. It has been known for scorers to use both methods in conjunction with one another, in case the computer goes down or runs out of battery.

In addition to PC software, mobile apps are being used. Most of the amateur tournaments use mobile apps on their smartphones because they are more convenient and free, which makes it perfect fit for amateur cricketers since they cannot afford to spend money on standalone and custom software. There are several cricket scoring apps[2] such as Total Cricket Scorer (TCS), a comprehensive program favoured many scorers in the County Championship[citation needed] in England, CricHQ, CricHeroes, CricScores, CricksLab, CricClubs, Chauka etc.. TCS was bought out by CricHQ in late 2015. Mobile apps allow amateur cricketers to keep their scores online, and also provide them with personalised statistics and graphs on their own mobile devices.

The ECB make free software available for cricket scoring both on PC and mobile devices from the PlayCricket website.

Detailed scoring

Cricket scorers keep track of many other facts of the game. As a minimum a scorer would note:

- For each ball, who bowled it and how many runs were scored from it, whether by the batsman with his bat ('off the bat') or byes.

- For each batsman, every scoring run made.

- For each dismissal, the kind of dismissal (e.g. LBW or run out), the bowler (in the case of a bowling, LBW, catch, wicket hit, or stumping), any other player involved (in the case of a catch, run out, or stumping), as well as the total the batting team reached at that point in the game ('the fall of wicket'). Example notations as seen on cricket scorecards:

- c fielder b bowler – Caught

- c & b bowler – Caught & bowled (the bowler was also the catching fielder)

- b bowler – Bowled

- lbw b bowler – Leg before wicket

- st wicket-keeper b bowler – Stumped

- hit wicket b bowler - Hit wicket

- run out (fielder) - Run out

- For each bowler (his 'figures'), the number of overs bowled, the number of wickets taken, the number of runs conceded, and the number of maiden overs bowled.

Traditionally, the score book might record each ball bowled by a bowler and each ball faced by a batsman, but not necessarily which batsman faced which ball. Linear scoring systems were developed from the late 19th century and early 20th century by John Atkinson Pendlington, Bill Ferguson and Bill Frindall, to keep track of the balls faced by a batsman off each bowler. Another early method of recording the number of balls faced and runs scored by each batsman off each bowler was devised by Australian scorer J.G. Jackschon in the 1890s, using a separate memorandum alongside the main scoresheet.

Frequently more detail is recorded, for instance, for a batsman, the number of balls faced and the number of minutes batted. Sometimes charts (known as wagon wheels) are prepared showing to which part of the field each scoring shot by a batsman was made (revealing the batman's favourite places to hit the ball)[3]

Technology such as Hawk-Eye allows for more detailed analysis of a bowler's performance. For instance the beehive chart shows where a bowler's balls arrived at a batsman (high, low, wide, on the off stump etc.), while the pitch map shows where the balls pitched (trending toward short, good, or full lengths). Both charts can also show the results of these balls (dots, runs, boundaries, or wickets)[4]

Scoring notation

A cricket scorer will typically mark the score sheet with a dot for a legal delivery with no wicket taken or runs scored (hence the term "a dot ball") where conventional runs are taken the score sheet is marked with the number of runs taken on that delivery.

Special notation is used in the case of extras.

Wides

The conventional scoring notation for a wide is an equal cross (likened to the umpire standing with arms outstretched signalling a wide).

If the batsmen run byes on a wide ball or the ball runs to the boundary for 4, a dot is added in each corner for each bye that is run, typically top left, then top right, then bottom left and finally all 4 corners.

If the batsman hits the stumps with his bat, or the wicket-keeper stumps him, the batsman would be out and a ‘W’ is added to the WIDE ‘cross’ symbol.

If a batsman is run out while taking byes on a wide delivery then the number of completed runs are shown as dots and an 'R' is added in the corner for the incomplete run.

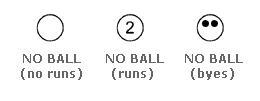

No-balls

The conventional notation for a no-ball is a circle. If the batsman hits the ball and takes runs, then the runs are marked inside the circle. In practice it is easier to write down the number then encircle it.

If a no-ball delivery eludes the wicket keeper and the batsmen run byes or the ball runs to the boundary for 4 byes, each bye taken is marked with a dot inside the circle. Again it is easier to encircle the dots.

Byes

The conventional notation for a single bye is a triangle with a horzontal edge at the base and a point at the top. If more than one bye is taken the number scored is written within the triangle - in practice it is easier to write the number down and then draw the triangle around it.

Leg byes

The conventional notation for a single leg bye is a triangle with a point at the base and horizontal edge at the top (an inverted bye symbol). If more than one leg bye is taken the number scored is written within the triangle - in practice it is easier to write the number down and then draw the triangle around it.

Match scores

Other than the information kept on a detailed scorecard, there are specific conventions for how the in-progress and overall result of a match is summarised and stated.

While an innings is in progress, the innings score comprises the number of runs scored by the batting team and the number of wickets taken by the bowling team. For example, a team that has scored 100 runs and lost three wickets is said to have a score of "one hundred for three", which is written 100–3 or 100/3. The exception is in Australia, where the order of the two numbers is switched: a spoken score of "three for one hundred" and written score of 3–100 or 3/100.

When an innings is complete:

- If all of a team's batsmen were dismissed (or retired/absent hurt), the number of wickets taken is dropped from the written score, for example, 300, rather than 300–10; this may be spoken as simply "three hundred", or as "three hundred, all out".

- If a team declares its innings closed despite still having able batsmen available, a d or dec is appended to the wickets in the score, for example 300-8d or 300-8dec; this would be spoken as "three hundred for eight, declared".

- If a limited-overs innings is complete due to all overs having been faced, the progress-style score is still used, for example 275-7.

In a completed two-innings match, each team's innings scores are always written and spoken separately – the sum of the two innings scores is never written or spoken, despite the fact that it is the determining factor in who wins the match. If the match has a winner, then the winning team's score is listed first; if not, then the team which batted first is listed first. If a team has followed on in its second innings, this is indicated by appending (f/o) to its score. In this way, a finished cricket score gives enough information to describe each innings and the sequence in which they were played. The score is then usually accompanied by a statement of the result and (if applicable) margin of victory. The margin of victory can be described in four ways:

- If the team batting last wins the game, then it wins by the number of wickets it had remaining when it passed the other team's total

- If the team bowling last wins the game, then it wins according to how many more runs it had scored than the opponent across the entire game

- If the team bowling last wins the game, and has only batted one innings compared to its opponent's two, then it wins by an innings and a number of runs

- If a match is tied or drawn, but a victory or tournament advancement is awarded based on a tie-breaker rule (for example, based on the first innings leader in the knock-out portion of India's Ranji Trophy), then the tie or draw is still given as the primary match result, with the special rule appended.

Some examples of full statements of scores in two-innings matches include:

- Sri Lanka 267 & 268–4 def. New Zealand 249 & 285, Sri Lanka won by 6 wickets

- Australia 284 & 487–7d def. England 374 & 146, Australia won by 251 runs

- India 601–5d def. South Africa 275 & 189 (f/o), India won by an innings and 137 runs

- South Africa 418 & 301–7d vs England 356 & 228–9, match drawn

- Delhi 532 & 273–4 vs Tamil Nadu 449, match drawn (Delhi won on first innings lead)

The statement of score and results is similar in a limited overs match, except that for a victory by wickets, it is also conventional to append the number of balls remaining in the team's innings – since the number of overs is often a greater constraint than remaining wickets. If the overs or targets are amended by a rain rule (typically the Duckworth-Lewis method), this is always noted in the statement of result – which is important since the official margin of a victory by runs under a rain rule may not equal the difference between the teams' actual scores. As for a two-innings match, if a tied match is decided by a tie-breaker, the score will still reflect the primary result as a tie and the tie-breaker as an appendix to the result; this is even in the case of a Super Over, the runs from which are not added to the main innings score. Examples of full statements of results from limited overs matches include:

- Australia 288 def. West Indies 273–9, Australia won by 15 runs

- India 230–4 def. South Africa, India won by 6 wickets (with 15 balls remaining)

- Pakistan 349 def. Zimbabwe 99, Pakistan won by 93 runs (D/L method)

- New Zealand 174–4 vs Sri Lanka 174–6, match tied (Sri Lanka won the Super Over)

In the statement of results for a match without a winner, there are four distinct terms which may be used: draw, tie, no result and abandoned. A tie is a match in which the game is completed and the two teams finish with the same number of runs. A draw is a two-innings match which does not reach a conclusion within its allotted time. No result is the outcome of a limited overs match which does not reach a conclusion, usually because rain prevents both teams from facing the prescribed minimum number of overs. An abandoned match is in which a ball is never bowled.

See also

References

- ^ ECB ACO Education – scorer courses ("Scorers Count")

- ^ Cricket Scoring Apps For Your Local Cricket Match

- ^ Wagonwheel

- ^ Hawk-eye innovations: beehive and pitch map

Bibliography

- For a comprehensive guide to the laws and their interpretation, and for guidance to scorers: Tom Smith's Cricket Umpiring and Scoring (Marylebone Cricket Club). ISBN 978-0-297-86641-1