Peshitta: Difference between revisions

Empty section Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 131: | Line 131: | ||

{{Books of the Bible}} |

{{Books of the Bible}} |

||

{{Authority control}} |

{{Authority control}} |

||

[[Category:2nd-century Christian texts]] |

|||

Revision as of 18:49, 11 November 2019

| Peshitta | |

|---|---|

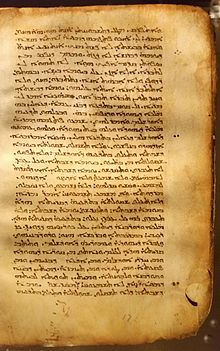

9th-century manuscript | |

| Full name | ܡܦܩܬܐ ܦܫܝܛܬܐ mappaqtâ pšîṭtâ |

| Other names | Peshitta, Peshittâ, Pshitta, Pšittâ, Pshitto, Fshitto |

| Complete Bible published | 2nd century AD |

| Translation type | Syriac language |

| Religious affiliation | Syriac Christianity |

ܒܪܵܫܝܼܬܼ ܒܪ݂ܵܐ ܐܲܠܵܗܵܐ ܝܵܬܼ ܫܡܲܝܵܐ ܘܝܵܬܼ ܐܲܪܥܵܐ ܘܐܲܪܥܵܐ ܗܘ̣ܵܬܼ ܬܘܿܗ ܘܒ݂ܘܿܗ ܘܚܸܫܘܿܟ݂ܵܐ ܥܲܠ ܐܲܦܲܝ̈ ܬܗܘܿܡܵܐ ܘܪܘܼܚܹܗ ܕܐܲܠܵܗܵܐ ܡܪܲܚܦܵܐ ܥܲܠ ܐܲܦܲܝ̈ ܡܲܝ̈ܵܐ ܘܐܸܡܲܪ݂ ܐܲܠܵܗܵܐ: ܢܸܗܘܸܐ ܢܘܼܗܪܵܐ ܘܲܗ̤ܘܵܐ ܢܘܼܗܪܵܐ

ܘܣܲܓܝܼܐܹ̈ܐ ܡܸܢ ܒܢܲܝ̈ ܝܼܣܪܵܝܹܠ ܢܲܦܢܹܐ ܠܘܵܬ݂ ܡܵܪܝܵܐ ܐܲܠܵܗܗܘܿܢ | |

| Part of a series on |

| Oriental Orthodoxy |

|---|

|

| Oriental Orthodox churches |

|

|

The Peshitta (Template:Lang-syc or ܦܫܝܼܛܬܵܐ pšīṭtā) is the standard version of the Bible for churches in the Syriac tradition.

The consensus within biblical scholarship, though not universal, is that the Old Testament of the Peshitta was translated into Syriac from Hebrew, probably in the 2nd century AD, and that the New Testament of the Peshitta was translated from the Greek.[1] This New Testament, originally excluding certain disputed books (2 Peter, 2 John, 3 John, Jude, Revelation), had become a standard by the early 5th century. The five excluded books were added in the Harklean Version (616 AD) of Thomas of Harqel.[2] However, the 1905 United Bible Society Peshitta used new editions prepared by the Irish Syriacist John Gwynn for the missing books.

Etymology

The name 'Peshitta' is derived from the Syriac mappaqtâ pšîṭtâ (ܡܦܩܬܐ ܦܫܝܛܬܐ), literally meaning 'simple version'. However, it is also possible to translate pšîṭtâ as 'common' (that is, for all people), or 'straight', as well as the usual translation as 'simple'. Syriac is a dialect, or group of dialects, of Eastern Aramaic, originating around Edessa. It is written in the Syriac alphabet, and is transliterated into the Latin script in a number of ways, generating different spellings of the name: Peshitta, Peshittâ, Pshitta, Pšittâ, Pshitto, Fshitto. All of these are acceptable, but 'Peshitta' is the most conventional spelling in English.

Brief history of the Peshitta

The Peshitta had from the 5th century onward a wide circulation in the East, and was accepted and honored by the whole diversity of sects of Syriac Christianity. It had a great missionary influence: the Armenian and Georgian versions, as well as the Arabic and the Persian, owe not a little to the Syriac. The famous Nestorian tablet of Chang'an witnesses to the presence of the Syriac scriptures in the heart of China in the 8th century. The Peshitta was first brought to the West by Moses of Mindin, a noted Syrian ecclesiastic who unsuccessfully sought a patron for the work of printing it in Rome and Venice. However, he was successful in finding such a patron in the Imperial Chancellor of the Holy Roman Empire at Vienna in 1555—Albert Widmanstadt. He undertook the printing of the New Testament, and the emperor bore the cost of the special types which had to be cast for its issue in Syriac. Immanuel Tremellius, the converted Jew whose scholarship was so valuable to the English reformers and divines, made use of it, and in 1569 issued a Syriac New Testament in Hebrew letters. In 1645, the editio princeps of the Old Testament was prepared by Gabriel Sionita for the Paris Polyglot, and in 1657 the whole Peshitta found a place in Walton's London Polyglot. For long the best edition of the Peshitta was that of John Leusden and Karl Schaaf, and it is still quoted under the symbol "Syrschaaf", or "SyrSch".

New Testament Peshitta

When the earliest extant New Testament Peshitta text, the Khabouris Codex was found, the news article "US Library gets an Ancient Bible" appeared in the New York Times on March 26, 1955 reporting on the oldest known New Testament Bible written in "the language used by Christ." The article noted that it was taken to the White House where President Eisenhower viewed it. The Codex was said to be insured for "an hour and a half" in the amount of $1,500,000 US dollars.[3] This discovery challenges the long held idea that the Peshitta (Aramaic New Testament Scriptures) were written after the Greek and Hebrew texts, and lending credence to the minority viewpoint held by the Church of the East which itself states to be in possession of the New Testament Scriptures as handed down by the Apostles themselves.

In a detailed examination of Matthew 1–14, Gwilliam found that the Peshitta agrees with the Textus Receptus only 108 times and with Codex Vaticanus 65 times. Meanwhile, in 137 instances it differs from both, usually with the support of the Old Syriac and the Old Latin, and in 31 instances it stands alone.[4]

To this end, and in reference to the originality of the Peshitta, the words of Patriarch Shimun XXI Eshai are summarized as follows:

- "With reference to....the originality of the Peshitta text, as the Patriarch and Head of the Holy Apostolic and Catholic Church of the East, we wish to state, that the Church of the East received the scriptures from the hands of the blessed Apostles themselves in the Aramaic original, the language spoken by our Lord Jesus Christ Himself, and that the Peshitta is the text of the Church of the East which has come down from the Biblical times without any change or revision."[5]

In the first century CE, Josephus, the Jewish historian, testified that Aramaic was widely spoken and understood accurately by Parthians, Babylonians, the remotest Arabians, and those of his nation beyond Euphrates with Adiabeni. He says:

"I have proposed to myself, for the sake of such as live under the government of the Romans, to translate those books into the Greek tongue, which I formerly composed in the language of our country, and sent to the Upper Barbarians. Joseph, the son of Matthias, by birth a Hebrew, a priest also, and one who at first fought against the Romans myself, and was forced to be present at what was done afterwards, [am the author of this work],"

Jewish Wars (Book 1, Preface, Paragraph 1)(1:3)

and continuing,

"I thought it therefore an absurd thing to see the truth falsified in affairs of such great consequence, and to take no notice of it; but to suffer those Greeks and Romans that were not in the wars to be ignorant of these things, and to read either flatteries or fictions, while the Parthians, and the Babylonians, and the remotest Arabians, and those of our nation beyond Euphrates, with the Adiabeni, by my means, knew accurately both whence the war begun, what miseries it brought upon us, and after what manner it ended."

Jewish Wars (Book 1 Preface, Paragraph 2) (1:6)

Yigael Yadin, an archeologist working on the Qumran find, also agrees with Josephus' testimony, pointing out that Aramaic was the lingua franca of this time period.[6] Josephus' testimony on Aramaic is also supported by the gospel accounts of the New Testament (specifically in Matthew 4:24-25, Mark 3:7-8, and Luke 6:17), in which people from Galilee, Judaea, Jerusalem, Idumaea, Tyre, Sidon, Syria, Decapolis, and "from beyond Jordan" came to see Jesus for healing and to hear his discourse.

A statement by Eusebius that Hegesippus "made some quotations from the Gospel according to the Hebrews and from the Syriac Gospel," means we should have a reference to a Syriac New Testament as early as 160–180 AD, the time of that Hebrew Christian writer. The translation of the New Testament is careful, faithful and literal, and the simplicity, directness and transparency of the style are admired by all Syriac scholars and have earned it the title of "Queen of the versions."[7]

Critical Edition of the New Testament

The standard United Bible Societies 1905 edition of the New Testament of the Peshitta was based on editions prepared by Syriacists Philip E. Pusey (d.1880), George Gwilliam (d.1914) and John Gwyn.[8] These editions comprised Gwilliam & Pusey's 1901 critical edition of the gospels, Gwilliam's critical edition of Acts, Gwilliam & Pinkerton's critical edition of Paul's Epistles and John Gwynn's critical edition of the General Epistles and later Revelation. This critical Peshitta text is based on a collation of more than seventy Peshitta and a few other Aramaic manuscripts. All 27 books of the common Western Canon of the New Testament are included in this British & Foreign Bible Society's 1905 Peshitta edition, as is the adultery pericope (John 7:53–8:11). The 1979 Syriac Bible, United Bible Society, uses the same text for its New Testament. The Online Bible reproduces the 1905 Syriac Peshitta NT in Hebrew characters.

Peshitta Translations

- James Murdock - The New Testament, Or, The Book of the Holy Gospel of Our Lord and God, Jesus the Messiah (1851).

- John Wesley Etheridge - A Literal Translation of the Four Gospels From the Peschito, or Ancient Syriac and The Apostolical Acts and Epistles From the Peschito, or Ancient Syriac: To Which Are Added, the Remaining Epistles and The Book of Revelation, After a Later Syriac Text (1849).

- George M. Lamsa - The Holy Bible From the Ancient Eastern Text (1933)- Contains both the Old and New Testaments according to the Peshitta text. This translation is better known as the Lamsa Bible. He also wrote several other books on the Peshitta and Aramaic primacy such as Gospel Light, New Testament Origin, and Idioms of the Bible, along with a New Testament commentary. To this end, several well-known Evangelical Protestant preachers have used or endorsed the Lamsa Bible, such as Oral Roberts, Billy Graham, and William M. Branham.

- Andumalil Mani Kathanar - Vishudha Grantham. New Testament translation in Malayalam.

- Mathew Uppani C. M. I - Peshitta Bible. Translation (including Old and New Testaments) in Malayalam (1997).

- Arch-corepiscopos Curien Kaniamparambil- Vishudhagrandham. Translation (including Old and New Testaments) in Malayalam.

- Janet Magiera- Aramaic Peshitta New Testament Translation, Aramaic Peshitta New Testament Translation- Messianic Version, and Aramaic Peshitta New Testament Vertical Interlinear (in three volumes)(2006). Magiera is connected to George Lamsa.

- The Way International - Aramaic-English Interlinear New Testament

- William Norton- A Translation, in English Daily Used, of the Peshito-Syriac Text, and of the Received Greek Text, of Hebrews, James, 1 Peter, and 1 John: With An Introduction On the Peshito-Syriac Text, and the Received Greek Text of 1881 and A Translation in English Daily Used: of the Seventeen Letters Forming Part of the Peshito-Syriac Books. William Norton was a Peshitta primacist, as shown in the introduction to his translation of Hebrews, James, I Peter, and I John.

- Gorgias Press - Antioch Bible, a Peshitta text and translation of the Old Testament, New Testament, and Apocrypha.

Peshitta Manuscripts

The following manuscripts are in the British Archives:

- British Library, Add. 14470 – complete text of 22 books, from the 5th/6th century

- Rabbula Gospels

- Khaboris Codex

- Codex Phillipps 1388

- British Library, Add. 12140

- British Library, Add. 14479

- British Library, Add. 14455

- British Library, Add. 14466

- British Library, Add. 14467

- British Library, Add. 14669

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Sebastian P. Brock The Bible in the Syriac Tradition St. Ephrem Ecumenical Research Institute, 1988. Quote Page 13: "The Peshitta Old Testament was translated directly from the original Hebrew text, and the Peshitta New Testament directly from the original Greek"

- ^ Geoffrey W. Bromiley The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: Q-Z 1995– Page 976 "Printed editions of the Peshitta frequently contain these books in order to fill the gaps. D. Harklean Version. The Harklean version is connected with the labors of Thomas of Harqel. When thousands were fleeing Khosrou's invading armies, ..."

- ^ "U. S. LIBRARY GETS AN ANCIENT BIBLE; Oldest Known Copy of New Testament to Go on View in Washington April 5". The New York Times. 1955-03-26.

- ^ Bruce M. Metzger, The Early Versions of the New Testament: Their Origin, Transmission and Limitations (Oxford University Press 1977), p. 50.

- ^ His Holiness Mar Eshai Shimun, Catholicos Patriarch of the Holy Apostolic Catholic Church of the East. April 5, 1957

- ^ "Bar Kokhba: The rediscovery of the legendary hero of the last Jewish Revolt Against Imperial Rome", 234

- ^ "Syriac Versions of the Bible, by Thomas Nicol". www.bible-researcher.com. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ^ Corpus scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium: Subsidia Catholic University of America, 1987 "37 ff. The project was founded by Philip E. Pusey who started the collation work in 1872. However, he could not see it to completion since he died in 1880. Gwilliam,

Sources

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2006) The Bible in the Syriac Tradition: English Version Gorgias Press LLC, ISBN 1-59333-300-5

- Dirksen, P. B. (1993). La Peshitta dell'Antico Testamento, Brescia, ISBN 88-394-0494-5

- Flesher, P. V. M. (ed.) (1998). Targum Studies Volume Two: Targum and Peshitta. Atlanta.

- Kiraz, George Anton (1996). Comparative Edition of the Syriac Gospels: Aligning the Old Syriac Sinaiticus, Curetonianus, Peshitta and Harklean Versions. Brill: Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2002 [2nd ed.], 2004 [3rd ed.].

- Lamsa, George M. (1933). The Holy Bible from Ancient Eastern Manuscripts. ISBN 0-06-064923-2.

- Pinkerton, J. and R. Kilgour (1920). The New Testament in Syriac. London: British and Foreign Bible Society, Oxford University Press.

- Pusey, Philip E. and G. H. Gwilliam (1901). Tetraevangelium Sanctum iuxta simplicem Syrorum versionem. Oxford University Press.

- Weitzman, M. P. (1999). The Syriac Version of the Old Testament: An Introduction. ISBN 0-521-63288-9.

- Attribution

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Nicol, Thomas. "Syriac Versions" in (1915) International Standard Bible Encyclopedia

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Nicol, Thomas. "Syriac Versions" in (1915) International Standard Bible Encyclopedia

External links

- Digital text of the Peshitta, Old and New Testament with full eastern vocalization

- The Peshitta divided in chapters, the New Testament with full western vocalization at syriacbible.nl

- Dukhrana Biblical Research

- Syriac Peshitta New Testament at archive.org

- Interlinear Aramaic/English New Testament also trilinear Old Testament (Hebrew/Aramaic/English)

- Downloadable cleartext of English translations (Scripture.sf.net)