Nguyễn dynasty: Difference between revisions

m clean up, replaced: “ → ", ” → ", representant → representative |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

{{Infobox former country |

{{Infobox former country |

||

|native_name = {{lang|vi|Việt Nam quốc}} ({{lang|vi|越南國}})<br>{{lang|vi|Đại Nam quốc}} ({{lang|vi|大南國}}) |

|native_name = {{lang|vi|Việt Nam quốc}} ({{lang|vi|越南國}})<br>{{lang|vi|Đại Nam quốc}} ({{lang|vi|大南國}}) |

||

|conventional_long_name = Vietnam (1802-1839)<br> |

|conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Vietnam (1802-1839)<br>Empire of Đại Nam (1839-1945) |

||

|common_name = Nguyễn Dynasty |

|common_name = Nguyễn Dynasty |

||

|status = Monarchy, [[protectorate]] |

|status = Monarchy, [[protectorate]] |

||

Revision as of 13:50, 28 June 2019

Kingdom of Vietnam (1802-1839) Empire of Đại Nam (1839-1945) Việt Nam quốc (越南國) Đại Nam quốc (大南國) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1802–1945 | |||||||||||

| Anthem: "Đăng dàn cung" | |||||||||||

Việt Nam at its greatest territorial extent in 1829 (under Emperor Minh Mạng), superimposed on the modern political map | |||||||||||

| Status | Empire (1802–1885)[a] Protectorate of France (1885–1945) | ||||||||||

| Capital | Huế | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Vietnamese | ||||||||||

| Religion | Neo-Confucianism, Buddhism, Catholicism | ||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||

• 1802–1820 | Gia Long (First) | ||||||||||

• 1926–1945 | Bảo Đại (Last) | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Nguyễn Ánh defeated Tây Sơn dynasty | 1802 | ||||||||||

• Coronation of Gia Long | 1 June 1802 | ||||||||||

| 1 September 1858 | |||||||||||

| 5 June 1862 | |||||||||||

| 25 August 1883 | |||||||||||

| 6 June 1884 | |||||||||||

| 26 September 1940 | |||||||||||

• Abdication of Bảo Đại | 30 August 1945 | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1830 | 7,600,000 | ||||||||||

• 1860 | 10,000,000 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Văn (Sapèque), Tiền, and Lạng Piastre (from 1885) | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Vietnam Laos Cambodia | ||||||||||

The Nguyễn dynasty or House of Nguyễn (Template:Lang-vi; Hán-Nôm: 阮朝, Nguyễn triều) was the last imperial family of Vietnam.[1] Their ancestral line can be traced back to the beginning of the Common Era. However, only by the mid-sixteenth century the most ambitious family branch, the Nguyễn Lords had risen to conquer, control and establish feudal rule over large territory.[2]

Imperial rule lasted for 143 years, when Gia Long ascended the throne in 1802, after putting an end to the rise of the Tây Sơn and uniting the country, Emperor Bảo Đại, the dynasty's last representative abdicated the throne and transferred sovereign power to the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in 1945.

Nguyễn dynastic rule was obtained by the support of the French, who compromised its authority from the beginning. Sovereignty was eventually lost to French colonialism as the nation was divided into three administrative entities of French Indochina: Cochinchina became a French colony, and Annam and Tonkin became nominally-independent protectorates.[3]

Origins and rise to power

First mentioned in the first century CE, the Nguyễn family clan, that originated in the Thanh Hóa Province exerted substantial political influence and military power, in particular throughout early modern Vietnamese history. Affiliations with the ruling elite date back to the tenth century when Nguyễn Bặc was appointed the first Grand Chancellor of the short-lived Đinh dynasty under Đinh Bộ Lĩnh and its successor Emperor Lê Lợi of the Early Lê dynasty.[4][5] Nguyễn Thị Anh, a queen consort of emperor Lê Thái Tông served as official regent of Annam for her son emperor Lê Nhân Tông between 1442 and 1453.[6]

In 1527 Mạc Đăng Dung, after defeating and executing the Lê vassal Nguyễn Hoang Du in a civil war emerged as the intermediate victor and established the Mạc dynasty by deposing emperor Lê Cung Hoàng of the once prosperous but rapidly declining later Lê dynasty. Nguyễn Hoang Du's son Nguyễn Kim and his Trịnh lord allies remained loyal to the Lê and attempted to restore the Lê dynasty to power, thereby reigniting the civil war.[7][8]

Nguyễn Kim, who had served as leader of the alliance during the six-year conquest of the Southern Dynasty against Mạc Đăng Dung, was assassinated in 1545 by a captured Mạc general. Kim's son-in-law, Trịnh Kiểm (who had killed the eldest son of Nguyễn Kim), took command of the alliance. In 1558, Lê Anh Tông, emperor of the re-established Lê dynasty entrusted Nguyễn Hoàng (Kim's second son) with the lordship of the southern part of central Vietnam, which had been conquered during the 15th century from the Champa principalities.[9]

Nguyễn Hoàng chose the city of Huế as his residence and established the dominion of the Nguyễn Chúa (Vietnamese: lords) in the southern part of the country. Although the Nguyễn and Trịnh lords ruled as de facto kings in their respective lands, they paid official tribute to the Lê emperors in a ceremonial gesture, as imperial power was confined to representation.

Nguyễn Hoàng and his successors continued their rivalry with the Trịnh lords, expanded their territory by making parts of Cambodia a protectorate, invaded Laos, captured the last vestiges of Champa in 1693 and ruled in an unbroken line until 1776.[10][11][12]

Struggle for sovereignty

First Tây Sơn–Nguyễn civil war (1771–1785)

The end of the Nguyễn lord reign

The 17th-century war between the Trịnh and the Nguyễn ended in an uneasy peace, as neither side was capable to unite the country under its rule. After 100 years of domestic peace, the Nguyễn lords were confronted with the Tây Sơn rebellion in 1774. Its military had had considerable losses in manpower after a series of campaigns in Cambodia and proved unable to contain the revolt. By the end of the year, the Trịnh lords had formed an alliance with the Tây Sơn rebels and captured Huế in 1775.[13]

Nguyễn lord Nguyễn Phúc Thuần fled south to the Quảng Nam province, where he left a garrison under co-ruler Nguyễn Phúc Dương. He fled further south to the Gia Định Province (around modern-day Ho Chi Minh City) by sea before the arrival of Tây Sơn leader Nguyễn Nhạc, whose forces defeated the Nguyễn garrison and seized Quảng Nam.[14]

In early 1777 a large Tây Sơn force under Nguyễn Huệ and Nguyễn Lữ attacked and captured Gia Định from the sea and defeated the Nguyễn Lord forces. The Tây Sơn received widespread popular support as they presented themselves as champions of the Vietnamese people, who rejected any foreign influence and fought for the full reinstitution of the Lê dynasty. Hence, the elimination of the Nguyễn and Trinh lordships was considered a priority and all but one member of the Nguyễn family captured at Saigon were executed.

Escape of Nguyễn Ánh

The 13-year-old Nguyễn Ánh escaped and with the help of the Vietnamese Catholic priest Paul Hồ Văn Nghị soon arrived at the Paris Foreign Missions Society in Hà Tiên. With Tây Son search parties closing in, he kept on moving and eventually met the French missionary Pigneau de Behaine. By retreating to the Thổ Chu Islands in the Gulf of Thailand, both escaped Tây Sơn capture.[15][16][17]

Pigneau de Behaine resolved to support Ánh, who had declared himself heir of the Nguyễn lordship.[18] A month later the Tây Sơn army under Nguyễn Huệ had returned to Quy Nhơn. Ánh seized the opportunity and quickly deployed an army at his new base in Long Xuyên, marched to Gia Định in December 1777, raided the palace of Long Hồ and occupied the city. The Tây Sơn returned to Gia Định in February 1778 and recaptured the province. When Ánh approached with his army, the Tây Sơn retreated.[19][19]

By the summer of 1781, Ánh's forces had grown to 30,000 soldiers, 80 battleships, three large ships and two Portuguese ships procured with the help of de Behaine. Ánh organized an unsuccessful ambush of the Tây Sơn base camps in the Phú Yên province. In March 1782 Tây Sơn emperor Thái Đức and his brother Nguyễn Huệ sent a naval force to attack Ánh. Ánh's army was defeated and he fled via Ba Giồng to Svay Rieng in Cambodia.

Nguyễn–Cambodian agreement

Ánh met with the Cambodian King Ang Eng, who granted him exile and offered support in his struggle with the Tây Sơn. In April 1782 a Tây Sơn army invaded Cambodia, detained and forced Ang Eng to pay tribute, and demanded, that all Vietnamese nationals living in Cambodia were to return to Vietnam.[20]

Chinese Vietnamese support for Nguyễn Ánh

Support by the Chinese Vietnamese began when the Qing dynasty overthrew the Ming dynasty. The Han Chinese refused to live under the Manchu Qing and fled to Southeast Asia (including Vietnam). Most were welcomed by the Nguyễn lords to resettle in southern Vietnam for business and trade.

In 1782, Nguyễn Ánh escaped to Cambodia and the Tây Sơn seized southern Vietnam (now Cochinchina). They discriminated against the ethnic Chinese, displeasing the Chinese Vietnamese. That April, Nguyễn loyalists Tôn Thất Dụ, Trần Xuân Trạch, Trần Văn Tự and Trần Công Chương sent military support to Ánh. The Nguyễn army killed grand admiral Phạm Ngạn, who had a close relationship with the emperor Thái Đức, at Tham Lương bridge.[20] Thái Đức, angry, thought that the ethnic Chinese had collaborated in the killing. He sacked the town of Cù lao (present-day Biên Hòa), which had a large Chinese population,[21][22] and ordered the oppression of the Chinese community to avenge their assistance to Ánh. Ethnic cleansing had previously occurred in Hoi An, leading to support by wealthy Chinese for Ánh. He returned to Giồng Lữ, defeated admiral Nguyễn Học of the Tây Sơn and captured eighty battleships. Ánh then began a campaign to reclaim southern Vietnam, but Nguyễn Huệ deployed a naval force to the river and destroyed his navy. Ánh again escaped with his followers to Hậu Giang. Cambodia later cooperated with the Tây Sơn to destroy Ánh's force and made him retreat to Rạch Giá, then to Hà Tiên and Phú Quốc.

Nguyễn–Thai alliance

Following consecutive losses to the Tây Sơn, Ánh sent his general Châu Văn Tiếp to Siam to request military assistance. Siam, under Chakri rule, wanted to conquer Cambodia and southern Vietnam. King Rama I agreed to ally with the Nguyễn lord and intervene militarily in Vietnam. Châu Văn Tiếp sent a secret letter to Ánh about the alliance. After meeting with Siamese generals at Cà Mau, Ánh, thirty officials and some troops visited Bangkok to meet Rama I in May 1784. The governor of Gia Định Province, Nguyễn Văn Thành, advised Ánh against foreign assistance.[23][24]

Rama I, fearing the growing influence of the Tây Sơn dynasty in Cambodia and Laos, decided to dispatch his army against it. In Bangkok, Ánh began to recruit Vietnamese refugees in Siam to join his army (which totaled over 9,000).[25] He returned to Vietnam and prepared his forces for the Tây Sơn campaign in June 1784, after which he captured Gia Định. Rama I nominated his nephew, Chiêu Tăng, as admiral the following month. The admiral led Siamese forces including 20,000 marine troops and 300 warships from the Gulf of Siam to Kiên Giang province. In addition, more than 30,000 Siamese infantry troops crossed the Cambodian border to An Giang province.[26] On 25 November 1784, Admiral Châu Văn Tiếp died in battle against the Tây Sơn in Mang Thít District, Vĩnh Long Province. The alliance was largely victorious from July through November, and the Tây Sơn army retreated north. However, emperor Nguyễn Huệ halted the retreat and counter-attacked the Siamese forces in December. In the decisive battle of Rạch Gầm–Xoài Mút, more than 20,000 Siamese soldiers died and the remainder retreated to Siam.[27]

Ánh, disillusioned with Siam, escaped to Thổ Chu Island in April 1785 and then to Ko Kut Island in Thailand. The Siamese army escorted him back to Bangkok, and he was briefly exiled in Thailand.

1787 French alliance

The war between the Nguyễn lord and the Tây Sơn dynasty forced Ánh to find more allies. His relationship with de Behaine improved, and support for an alliance with France increased. Before the request for Siamese military assistance, de Behaine was in Chanthaburi and Ánh asked him to come to Phú Quốc Island.[28] Ánh asked him to contact King Louis XVI of France for assistance; de Behaine agreed to coordinate an alliance between France and Vietnam, and Ánh gave him a letter to present at the French court. Ánh's oldest son, Nguyễn Phúc Cảnh, was chosen to accompany de Behaine. Due to inclement weather, the voyage was postponed until December 1784. The group departed from Phú Quốc Island for Malacca and thence to Pondicherry, and Ánh moved his family to Bangkok.[29] The group arrived in Lorient in February 1787, and Louis XVI agreed to meet them in May.

Treaty of Versailles (1787)

On 28 November 1787, de Behaine signed the Treaty of Versailles with French Minister of Foreign Affairs Armand Marc at the Palace of Versailles on behalf of Nguyễn Ánh.[30] The treaty stipulated that France provide four frigates, 1,200 infantry troops, 200 artillery, 250 cafres (African soldiers), and other equipment. Nguyễn Ánh ceded the Đà Nẵng estuary and Côn Sơn Island to France.[31] The French were allowed to trade freely and control foreign trade in Vietnam. Vietnam had to build one ship per year which was similar to the French ship which brought aid and give it to France. Vietnam was obligated to supply food and other aid to France when the French were at war with other East Asian nations.

French Revolution

On 27 December 1787, Pigneau de Behaine and Nguyễn Phúc Cảnh left France for Pondicherry to wait for the military support promised by the treaty. However, due to the French Revolution and the abolition of the French monarchy, the treaty was never executed. Thomas Conway, who was responsible for French assistance, refused to provide it. Although the treaty was not implemented, de Behaine recruited French businessman who intended to trade in Vietnam and raised funds to assist Nguyễn Ánh. He spent fifteen thousand francs of his own money to purchase guns and warships. Cảnh and de Behaine returned to Gia Định in 1788 (after Nguyễn Ánh had recaptured it), followed by a ship with the war materiel. Frenchmen who were recruited included Jean-Baptiste Chaigneau, Philippe Vannier, Olivier de Puymanel, and Jean-Marie Dayot. A total of twenty people joined Ánh's army. The French purchased and supplied equipment and weaponry, reinforcing the defense of Gia Định, Vĩnh Long, Châu Đốc, Hà Tiên, Biên Hòa, Bà Rịa and training Ánh's artillery and infantry according to the European model.[32]

Second civil war (1787–1802)

Weakening of the Tây Sơn dynasty

In 1786, Nguyễn Huệ led the army against the Trịnh lords; Trịnh Khải escaped to the north and committed suicide. After the Tây Sơn army returned to Quy Nhơn, subjects of the Trịnh lord restored Trịnh Bồng (son of Trịnh Giang) as the next lord. Lê Chiêu Thống, emperor of the Lê dynasty, wanted to regain power from the Trịnh. He summoned Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh, governor of Nghệ An, to attack the Trịnh lord at the Imperial Citadel of Thăng Long. Trịnh Bồng surrendered to the Lê and became a monk. Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh wanted to unify the country under Lê rule, and began to prepare the army to march south and attack the Tây Sơn. Huệ led the army, killed Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh, and captured the later Lê capital. The Lê royal family were exiled to China, and the later Lê dynasty collapsed.

At that time, Nguyễn Huệ's influence became stronger in northern Vietnam; this made emperor Nguyễn Nhạc of the Tây Sơn dynasty suspect Huệ's loyalty. The relationship between the brothers became tense, eventually leading to battle. Huệ had his army surround Nhạc's capital, at Quy Nhơn citadel, in 1787. Nhạc begged Huệ not to kill him, and they reconciled. In 1788, Lê emperor Lê Chiêu Thống fled to China and asked for military assistance. Qing emperor Qianlong ordered Sun Shiyi to lead the military campaign into Vietnam. The campaign failed, diplomatic relations with Vietnam were normalized, and the Tây Sơn dynasty began to weaken.

Ánh's counter-attack

Ánh began to reorganize a strong armed force in Siam. He left Siam (after thanking King Rama I), and returned to Vietnam.[33][34] During the 1787 war between Nguyễn Huệ and Nguyễn Nhạc in northern Vietnam, Ánh recaptured the southern Vietnamese capital of Gia Định. Southern Vietnam had been ruled by the Nguyễns and they remained popular, especially with the ethnic Chinese. Nguyễn Lữ, the youngest brother of Tây Sơn (who ruled southern Vietnam), could not defend the citadel and retreated to Quy Nhơn. The citadel of Gia Định was seized by the Nguyễn lords.[35]

In 1788 de Behaine and Ánh's son, Prince Cảnh, arrived in Gia Định with modern war equipment and more than twenty Frenchmen who wanted to join the army. The force was trained and strengthened with French assistance.[36]

Defeat of the Tây Sơn

After the fall of the citadel at Gia Định, Nguyễn Huệ prepared an expedition to reclaim it before his death on 16 September 1792. His young son, Nguyễn Quang Toản, succeeded him as emperor of the Tây Sơn and was a poor leader.[37] In 1793, Nguyễn Ánh began a campaign against Quang Toản. Due to conflict between officials of the Tây Sơn court, Quang Toản lost battle after battle. In 1797, Ánh and Nguyễn Phúc Cảnh attacked Qui Nhơn (then in Phú Yên Province) in the battle of Thị Nại. They were victorious, capturing a large amount of Tây Sơn equipment.[38] Quang Toản became unpopular due to his murders of generals and officials, leading to a decline in the army. In 1799, Ánh captured the citadel of Quy Nhơn. He seized the capital (Phú Xuân) on 3 May 1802, and Quang Toản retreated north. Ánh then executed all the members of the Tây Sơn dynasty that year.

Origin of the dynasty

Unification of Vietnam

Nguyễn Phúc Ánh united Vietnam after a three-hundred-year division of the country. He celebrated his coronation at Huế on 1 June 1802 and proclaimed himself emperor (Template:Lang-vi), with the era name Gia Long (嘉隆) and the Thế temple name Nguyễn Thế Tổ (阮世祖). Gia Long prioritized the nation's defense, and feared that it could again be divided by civil war. He replaced the feudal system with a reformist Doctrine of the Mean, based on Confucianism.[39][40]

Government

Emperor

The Nguyễn dynasty maintained the bureaucracy and hierarchic system of former dynasties. The head of state was the emperor, who wielded absolute authority. Under the emperor was the Ministry of Interior (which worked on papers, royal messages and recording) and four Grand Secretariats (Template:Lang-vi), later renamed the Ministry of Secret Council.[citation needed] East Asia's monarchic system consisted of nobles and mandarins. Mandarins were civil or military.

Civil service and bureaucracy

| Rank | Civil position | Military position |

|---|---|---|

| Upper first rank (Bậc trên nhất phẩm) | Imperial Clan Court (Tông Nhân Phủ, Tôn nhân lệnh) Three Ducal Ministers (Tam công): * Grand Preceptor (Thái sư) * Grand Tutor (Thái phó) * Grand Protector (Thái bảo) |

Same |

| First senior rank (Chánh nhất phẩm) | Left Right Imperial Clan Court (Tôn nhân phủ, Tả Hữu tôn chính") Three Vice-Ducal Ministers (Tam Thiếu) * Vice Preceptor (Thiếu sư) * Vice Tutor (Thiếu phó) * Vice Protector (Thiếu bảo) |

Same |

| First junior rank (Tòng nhất phẩm) | Council of State (Tham chính viện) House of Councillors (Tham Nghị viện) Grand Secretariat (Thị trung Đại học sĩ) |

Banner Unit Lieutenant General, General-in-Chief, Provincial Commander-in-Chief |

| Second senior rank (Chánh nhị phẩm) | 6 ministries (Lục bộ): * Ministry of Personnel (Bộ Lại) * Ministry of Rites (Bộ Lễ) * Ministry of Justice (imperial China) (Bộ Hình) * Ministry of Finance (Bộ Hộ) * Ministry of Public Works (Bộ Công) * Ministry of Defense (Bộ Binh) Supreme Censorate (Đô sát viện, Tả Hữu Đô ngự sử) |

Banner Captain General, Commandants of Divisions, Brigade General |

| Second junior rank (Tòng nhị phẩm) | 6 Ministerial Advisors (Lục bộ Tả Hữu Tham tri) Grand coordinator and provincial governor (Tuần phủ) Supreme Vice-Censorate (Đô sát viện, Tả Hữu Phó đô ngự sử) |

Major General, Colonel |

| Third senior rank (Chánh tam phẩm) | Senior Head of 6 Ministries (Chánh thiêm sự) Administration Commissioner (Cai bạ) Surveillance Commissioner (Ký lục) State Auxiliary Academician of Secretariat (Thị trung Trực học sĩ) Court Auxiliary Academician (Trực học sĩ các điện) Court academician (Học sĩ các điện) Provincial governor (Hiệp trấn các trấn) |

Brigadiers of Artillery & Musketry, Brigadier of Scouts, Banner Division Colonel |

| Third junior rank (Tòng tam phẩm) | Junior Head of Six Ministries (Thiếu thiêm sự) Senior Palace Administration Commissioner (Cai bạ Chính dinh) Chargé d'affaires (Tham tán) Court of Imperial Seals (Thượng bảo tự) General Staff (Tham quân) |

Banner Brigade Commander |

| Fourth senior rank (Chánh tứ phẩm) | Provincial Education Commissioner of Guozijian (Quốc tử giám Đốc học) Head of six ministries (Thiếu thiêm sự) Junior Court of Imperial Seals (Thượng bảo thiếu Khanh) Grand Secretaries (Đông các học sĩ) Administration Commissioner of Trường Thọ palace (Cai bạ cung Trường Thọ) Provincial Advisor to Defense Command Lieutenant Governor (Tham hiệp các trấn) |

Lieutenant Colonel of Artillery, Musketry & Scouts Captain, Police Major |

| Fourth junior rank (Tòng tứ phẩm) | Provincial Vice Education Commissioner of Guozijian (Quốc tử giám phó Đốc học), Prefect (Tuyên phủ sứ), | Captain, Assistant Major in Princely Palaces |

| Fifth senior rank (Chánh ngũ phẩm) | Inner Deputy Supervisors of Instruction at Hanlin Institutes, Sub-Prefects | Police Captain, Lieutenant or First Lieutenant |

| Fifth junior rank (Tòng ngũ phẩm) | Assistant Instructors and Librarians at Imperial and Hanlin Institutes, Assistant Directors of Boards and Courts, Circuit Censors | Gate Guard Lieutenants, Second Captain |

| Sixth senior rank (Chánh lục phẩm) | Secretaries & Tutors at Imperial & Hanlin Institutes, Secretaries and Registrars at Imperial Offices, Police Magistrate | Bodyguards, Lieutenants of Artillery, Musketry & Scouts, Second Lieutenants |

| Sixth junior rank (Tòng lục phẩm) | Assistant Secretaries in Imperial Offices and Law Secretaries, Provincial Deputy Sub-Prefects, Buddhist & Taoist priests | Deputy Police Lieutenant |

| Seventh senior rank (Chánh thất phẩm) | None | City Gate Clerk, Sub-Lieutenants |

| Seventh junior rank (Tòng thất phẩm) | Secretaries in Offices of Assistant Governors, Salt Controllers & Transport Stations | Assistant Major in Nobles' Palaces |

| Eighth senior rank (Chánh bát phẩm) | None | Ensigns |

| Eighth junior rank (Tòng bát phẩm) | Sub-director of Studies, Archivists in Office of Salt Controller | First Class Sergeant |

| Ninth senior rank (Chánh cửu phẩm) | None | Second Class Sergeant |

| Ninth junior rank (Tòng cửu phẩm) | Prefectural Tax Collector, Deputy Jail Warden, Deputy Police Commissioner, Tax Examiner | Third Class Sergeant, Corporal, First & Second Class Privates |

Taxes

Vietnam's monetary subunit was the quan (貫). One quan equaled 10 coins, equivalent to ₫600. Officials received the following taxes (Template:Lang-vi):

- First senior rank (Chánh nhất phẩm): 400 quan; rice: 300 kg; per-capita tax: 70 quan

- First junior rank (Tòng nhất phẩm): 300 quan; rice: 250 kg; tax: 60 quan

- Second senior rank (Chánh nhị phẩm): 250 quan; rice: 200 kg; tax: 50 quan

- Second junior rank (Tòng nhị phẩm): 180 quan; rice: 150 kg; tax: 30 quan

- Third senior rank (Chánh tam phẩm): 150 quan; rice: 120 kg; tax: 20 quan

- Third junior rank (Tòng tam phẩm): 120 quan; rice: 90 kg; tax: 16 quan

- Fourth senior rank (Chánh tứ phẩm): 80 quan; rice: 60 kg; tax: 14 quan

- Fourth junior rank (Tòng tứ phẩm): 60 quan; rice: 50 kg; tax: 10 quan

- Fifth senior rank (Chánh ngũ phẩm): 40 quan; rice: 43 kg; tax: 9 quan

- Fifth junior rank (Tòng ngũ phẩm): 35 quan; rice: 30 kg; tax: 8 quan

- Sixth senior rank (Chánh lục phẩm): 30 quan; rice: 25 kg; tax: 7 quan

- Sixth junior rank (Tòng lục phẩm): 30 quan; rice: 22 kg; tax: 6 quan

- Seventh senior rank (Chánh thất phẩm): 25 quan; rice: 20 kg; tax: 5 quan

- Seventh junior rank (Tòng thất phẩm): 22 quan; rice: 20 kg; tax: 5 quan

- Eighth senior rank (Chánh bát phẩm): 20 quan; rice: 18 kg; tax: 5 quan

- Eighth junior rank (Tòng bát phẩm): 20 quan; rice: 18 kg; tax: 4 quan

- Ninth senior rank (Chánh cửu phẩm): 18 quan; rice: 16 kg; tax: 4 quan

- Ninth junior rank (Tòng cửu phẩm): 18 quan; rice: 16 kg; tax: 4 quan

Pension

When mandarins retired, they could receive one hundred to four hundred quan from the emperor. When they died, the royal court provided twenty to two hundred quan for a funeral.[citation needed]

Culture

After Gia Long, other dynastic rulers encountered problems with Catholic missionaries and other Europeans in Indochina. China's Qing Jiaqing Emperor refused Gia Long's request to change his country's name to Nam Việt, changing its name to Việt Nam.[41]

Gia Long's son, Minh Mạng, was then faced with the Lê Văn Khôi revolt in which native Christians and their European clergy tried to replace him and install a grandson of Gia Long who had converted to Roman Catholicism. The missionaries then incited frequent revolts in an attempt to Catholicize the throne and the country,[42] although Minh Mạng set aside public lands as part of his reforms.[43]

Minh Mang engineered the final conquest of the Champa Kingdom after the centuries-long Cham–Vietnamese wars. Cham Muslim leader Katip Suma was educated in Kelantan, returning to Champa to declare a jihad against the Vietnamese after Minh Mang's annexation of the region.[44][45][46][47] The Vietnamese forced Champa's Muslims to eat lizard and pig meat and its Hindus to eat beef to assimilate them into Vietnamese culture.[48]

Minh Mang sinicized ethnic minorities (such as Cambodians), claimed the legacy of Confucianism and China's Han dynasty for Vietnam, and used the term "Han people" (漢人, Hán nhân) to refer to the Vietnamese.[49][50] According to the emperor, "We must hope that their barbarian habits will be subconsciously dissipated, and that they will daily become more infected by Han [Sino-Vietnamese] customs."[51] These policies were directed at the Khmer and hill tribes.[52] Nguyen Phuc Chu had referred to the Vietnamese as "Han people" in 1712, distinguishing them from the Chams.[53] The Nguyen lords established colonies after 1790. Gia Long said, "Hán di hữu hạn" (漢 夷 有 限, "The Vietnamese and the barbarians must have clear borders"), distinguishing the Khmer from the Vietnamese.[54] Minh Mang implemented an acculturation policy for minority non-Vietnamese peoples.[55] "Thanh nhân" (清 人) or "Đường nhân" (唐人) were used to refer to ethnic Chinese by the Vietnamese, who called themselves "Hán dân" (漢 民) and "Hán nhân" (漢人) during 19th-century Nguyễn rule.[56] Since 1827, descendants of Ming dynasty refugees were called Minh nhân (明人) or Minh Hương (明 鄉) by Nguyễn rulers, to distinguish with ethnic Chinese.[57] Minh nhân were treated as Vietnamese since 1829.[58][59]: 272 They were not allowed to go to China, and also not allowed to wear the Manchu queue.[60]

"Trung Quốc" (中國) was used as a name for Vietnam by Gia Long in 1805.[61] Due to its dominance during the 19th century, Vietnam regards Cambodia and Laos as tributary states.[62]

The Nguyen dynasty popularized Chinese clothing.[63][64][65][66][67][68] Trousers were adopted by female White H'mong speakers,[69] replacing their traditional skirts.[70] The traditional Han Chinese Ming tunics and trousers were worn by the Vietnamese. The áo dài was developed in the 1920s, when compact, close-fitting tucks were added to Chinese-style clothing.[71] Chinese trousers and tunics were ordered by Nguyễn Phúc Khoát during the 18th century, replacing Vietnamese sarongs.[72] Although the Chinese trousers and tunic were mandated by the Nguyen government, skirts were worn in isolated north Vietnamese hamlets until the 1920s.[73] Chinese Ming-, Tang-, and Han-dynasty clothing was ordered for the Vietnamese military and bureaucrats by Nguyễn Phúc Khoát.[74]

An 1841 polemic, "On Distinguishing Barbarians", was based on the Qing sign "Vietnamese Barbarians' Hostel" (越夷會館) on the Fujian residence of Nguyen diplomat and Hoa Chinese Lý Văn Phức (李文馥).[75][76][77][78] It argued that the Qing did not subscribe to the neo-Confucianist texts from the Song and Ming dynasties which were learned by the Vietnamese,[79] who saw themselves as sharing a civilization with the Qing.[80] Non-Chinese highland tribes and other non-Vietnamese peoples living near (or in) Vietnam were called "barbarian" by the Vietnamese imperial court.[81][82] The essay distinguishes the Yi and Hua, and mentions Zhao Tuo, Wen, Shun and Taibo.[83][84][85][86][87] Kelley and Woodside described Vietnam's Confucianism.[88]

Emperors Minh Mạng, Thiệu Trị and Tự Đức, were opposed to French involvement in Vietnam, and tried to reduce the country's growing Catholic community. The imprisonment of missionaries who had illegally entered the country was the primary pretext for the French to invade (and occupy) Indochina. Like Qing China, a number of incidents involved other European nations during the 19th century.

The last independent Nguyễn emperor was Tự Đức. A succession crisis followed his death, as the regent Tôn Thất Thuyết orchestrated the murders of three emperors in a year. This allowed the French to take control of the country and its monarchy. All emperors since Đồng Khánh were chosen by the French, and only ruled symbolically.

French protectorate

Napoleon III took the first steps to establish a French colonial influence in Indochina. He approved the launching of a naval expedition in 1858 to punish the Vietnamese for their mistreatment of European Catholic missionaries and force the court to accept a French presence in the country. Factors in his decision were the belief that France risked becoming a second-rate power by not expanding its influence in East Asia, and the expanding idea that France had a civilizing mission. This led to an invasion in 1861.

By 1862, the war was over. Vietnam conceded three provinces in the south (French Cochinchina), opened three ports to French trade, allowed free passage of French warships to Kampuchea (which led to an 1863 French protectorate of Kampuchea), allowed freedom for French missionaries, and gave France a large indemnity for the cost of the war. France did not intervene in the Christian-supported Vietnamese rebellion in Bắc Bộ (despite missionary urging) or the subsequent slaughter of thousands of Christians after the rebellion, suggesting that persecution of Christians prompted the intervention but military and political reasons drove colonialism in Vietnam.

In 1885, France conquered the rest of Vietnam and promoted development of the Mekong Delta by the Vietnamese. The Nguyễn dynasty nominally ruled the French protectorates of Annam and Tonkin, which were (like Cochinchina) territories of French Indochina. France added new ingredients to Vietnam's cultural stew: Catholicism and a Latin-based alphabet. The spelling used in the Vietnamese transliteration was Portuguese, because the French relied on a dictionary compiled earlier by a Portuguese cleric.

World War I

While seeking to maximize the use of Indochina's natural resources and manpower to fight World War I, France cracked down on Vietnam's patriotic mass movements. Indochina (mainly Vietnam) had to provide France with 70,000 soldiers and 70,000 workers, who were forcibly drafted from villages to serve on the French battlefront. Vietnam also contributed 184 million piastres in loans and 336,000 tons of food.

These burdens proved heavy, since agriculture experienced natural disasters from 1914 to 1917. Lacking a unified nationwide organization, the vigorous Vietnamese national movement failed to use the difficulties France had as a result of war to stage significant uprisings.

In May 1916, sixteen-year-old emperor Duy Tân escaped from his palace in order to participate in an uprising of Vietnamese troops. The French were informed of the plan, and its leaders were arrested and executed. Duy Tân was deposed and exiled to the island of Réunion in the Indian Ocean.

World War II

Nationalist sentiment intensified in Vietnam (especially during and after the First World War), but uprisings and tentative efforts failed to obtain concessions from the French. The Russian Revolution greatly impacted 20th-century Vietnamese history.

For Vietnam, the outbreak of World War II on 1 September 1939 was as decisive as the 1858 French seizure of Đà Nẵng. The Axis power of Japan invaded Vietnam on 22 September 1940, attempting to construct military bases to strike against Allied forces in Southeast Asia.

The Viet Minh, a communist resistance movement, developed under Ho Chi Minh from 1941 to 1945. During a 1944–1945 famine in northern Vietnam, over one million people starved to death. In March 1945, realizing that Allied victory was inevitable, the Japanese overthrew the French in Vietnam, imprisoned their civil servants and proclaimed an independent Vietnam (under Japanese protection, with Bảo Đại its emperor).

Dynastic succession

The French persuaded Bảo Đại to return as chief of state (Quốc Trưởng) of the State of Vietnam (Quốc Gia Việt Nam), set up by France in areas over which it had regained control during a bloody war with the Viet Minh under Ho Chi Minh, in 1948. Bảo Đại spent much of his time during the conflict at his luxurious home in Đà Lạt (in the Vietnamese Highlands) or in Paris. This ended with the French defeat at Điện Biên Phủ in 1954.

The French negotiated with the U.S. to divide Vietnam. It was divided into North Vietnam (governed by the Viet Minh) and South Vietnam, with a new government. Bảo Đại's prime minister, Ngô Đình Diệm, defeated him in a 1955 referendum generally regarded as rigged; an improbable 98 percent of voters supported Diem's proposal for a republic, and the number of votes for the republic far exceeded the number of registered voters. Diem became president of the Republic of Vietnam (Việt Nam Cộng Hòa), ending Bảo Đại's involvement in Vietnamese affairs.

Bảo Đại went into exile in France, where he died in 1997 and was buried in Cimetière de Passy. Crown Prince Bảo Long succeeded him as head of the imperial house of Vietnam on 31 July of that year and was succeeded by his brother, Bảo Thắng, on 28 July 2007.

Bảo Thắng died on 15 March 2017 without an heir leaving the succession to the youngest half brother Bảo Ân.

Legacy

Art

Historical records

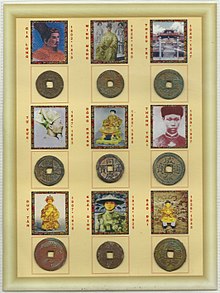

Emperors

The following list is the emperors' era names, which have meaning in Chinese and Vietnamese. For example, the first ruler's era name, Gia Long, is the combination of the old names for Saigon (Gia Định) and Hanoi (Thăng Long) to show the new unity of the country; the fourth, Tự Đức, means "Inheritance of Virtues"; the ninth, Đồng Khánh, means "Collective Celebration".

| Temple name | Posthumous name | Personal name | Lineage | Reign | Regnal name | Tomb | Events | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Thế Tổ | Khai Thiên Hoằng Đạo Lập Kỷ Thùy Thống Thần Văn Thánh Vũ Tuấn Đức Long Công Chí Nhân Đại Hiếu Cao Hoàng Đế | Nguyễn Phúc Ánh | Nguyễn lords | 1802–20 | Gia Long | Thiên Thọ lăng | Unified and named Vietnam, founded its last dynasty |

|

Thánh Tổ | Thể Thiên Xương Vận Chí Hiếu Thuần Đức Văn Vũ Minh Đoán Sáng Thuật Đại Thành Hậu Trạch Phong Công Nhân Hoàng Đế | Nguyễn Phúc Đảm | Son | 1820–41 | Minh Mệnh | Hiếu Lăng | Annexed the remaining Panduranga kingdom, renamed Vietnam Đại Nam (Great Nam/Great South), suppressed religion |

|

Hiến Tổ | Thiệu Thiên Long Vận Chí Thiện Thuần Hiếu Khoan Minh Duệ Đoán Văn Trị Vũ Công Thánh Triết Chượng Chương Hoàng Đế | Nguyễn Phúc Miên Tông | Son | 1841–47 | Thiệu Trị | Xương Lăng | |

|

Dực Tông | Thể Thiên Hanh Vận Chí Thành Đạt Hiếu Thể Kiện Đôn Nhân Khiêm Cung Minh Lược Duệ Văn Anh Hoàng Đế | Nguyễn Phúc Hồng Nhậm | Son | 1847–83 | Tự Đức | Khiêm Lăng | Faced French invasion and ceded Cochinchina to France |

|

Cung Tông | Huệ Hoàng Đế | Nguyễn Phúc Ưng Chân | Nephew (adopted son of Tự Đức) | 1883 | Dục Đức | An Lăng | Three-day emperor (20–23 July 1883) |

| – | Văn Lãng Quận Vương | Nguyễn Phúc Hồng Dật | Uncle (son of Thiệu Trị) | 1883 | Hiệp Hòa | Four-month emperor (30 July – 29 November 1883) | ||

| Giản Tông | Thiệu Đức Chí Hiếu Uyên Duệ Nghị Hoàng Đế | Nguyễn Phúc Ưng Đăng | Nephew (son of Hiệp Hòa's brother) | 1883–84 | Kiến Phúc | Bồi Lăng | Eight-month emperor (2 December 1883 – 31 July 1884) | |

|

– | — | Nguyễn Phúc Ưng Lịch | Younger brother | 1884–85 | Hàm Nghi | Thonac Cemetery, France | Dethroned after one year, continuing his rebellion until was captured in 1888 and fled to Algeria |

|

Cảnh Tông | Hoằng Liệt Thống Thiết Mẫn Huệ Thuần Hoàng Đế | Nguyễn Phúc Ưng Kỷ | Older brother | 1885–89 | Đồng Khánh | Tư Lăng | Pro-West |

|

– | Hoài Trạch Công | Nguyễn Phúc Bửu Lân | Cousin (son of Dục Đức) | 1889–1907 | Thành Thái | An Lăng | |

|

– | — | Nguyễn Phúc Vĩnh San | son | 1907–16 | Duy Tân | An Lăng | |

|

Hoằng Tông | Tự Đại Gia Vận Thánh Minh Thần Trí Nhân Hiếu Thành Kính Di Mô Thừa Liệt Tuyên Hoàng Đế | Nguyễn Phúc Bửu Đảo | Cousin (son of Đồng Khánh) | 1916–25 | Khải Định | Ứng Lăng | Collaborated with the French, and was a political figurehead for French colonial rulers. Unpopular with the Vietnamese people, nationalist leader Phan Châu Trinh accused him of selling Vietnam to the French and living in imperial luxury while the people were exploited. |

|

– | — | Nguyễn Phúc Vĩnh Thụy | Son | 1926–45 | Bảo Đại | Cimetière de Passy, France | Created the Empire of Vietnam under Japanese occupation during World War II; abdicated and transferred power to the Viet Minh in 1945, ending the Vietnamese monarchy. Removed as head of state of the State of Vietnam, changing it to a republic with Ngo Dinh Diem as president. Unpopular, considered an impotent puppet of the French colonial regime. |

After the death of Emperor Tự Đức (and according to his will), Dục Đức ascended to the throne on 19 July 1883. He was dethroned and imprisoned three days later, after being accused of deleting a paragraph from Tự Đức's will. With no time to announce his dynastic title, his era name was named for his residential palace.

Lineage

| 1 Gia Long 1802–1819 |

|||||||||||||

| 2 Minh Mệnh 1820–1840 |

|||||||||||||

| 3 Thiệu Trị 1841–1847 |

|||||||||||||

| 4 Tự Đức 1847–1883 |

Thoại Thái Vương | Kiên Thái Vương | 6 Hiệp Hoà 1883 | ||||||||||

| 5 Dục Đức 1883 |

9 Đồng Khánh 1885–1889 |

8 Hàm Nghi 1884–1885 |

7 Kiến Phúc 1883–1884 | ||||||||||

| 10 Thành Thái 1889–1907 |

12 Khải Định 1916–1925 |

||||||||||||

| 11 Duy Tân 1907–1916 |

13 Bảo Đại 1926–1945 |

||||||||||||

Note:

- Years are reigning years.

See also

- List of monarchs of Vietnam

- Nguyễn Trường Tộ – served Emperor Tự Đức

Notes

- ^ Member of the Imperial Chinese tributary system (1802–1839)

References

- ^ Li, Tana; Reid, Anthony (1993). Southern Vietnam under the Nguyễn. Economic History of Southeast Asia Project. Australian National University. ISBN 981-3016-69-8.

- ^ "Brief history of the Nguyen dynasty". Hue Monuments Conservation Centre. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ "The conquest of Vietnam by France". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ "Ai là tể tướng đầu tiên trong lịch sử Việt Nam? (Who is the first prime minister in Vietnamese history?)". Vietnam Union of Science and Technology Associations. 5 February 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ "VIETNAM BRIEF HISTORY". 4 DW. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ "The development of Le government in fifteenth century Vietnam". Research Gate. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ Bui Ngoc Son. "Confucian Constitutionalism in Imperial Vietnam" (PDF). National Taiwan University. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ K. W. Taylor (9 May 2013). A History of the Vietnamese. Cambridge University Press. pp. 232–. ISBN 978-0-521-87586-8.

- ^ "A GLIMPSE OF VIETNAM'S HISTORY". Web Cite. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ Danny Wong Tze Ken. "Vietnam-Champa Relations and the Malay-Islam Regional Network in the 17th–19th Centuries – The Vietnamese Victory over Champa in 1693". web archive. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ George Coedes (15 May 2015). The Making of South East Asia (RLE Modern East and South East Asia). Taylor & Francis. pp. 175–. ISBN 978-1-317-45094-8.

- ^ Michael Arthur Aung-Thwin; Kenneth R. Hall (13 May 2011). New Perspectives on the History and Historiography of Southeast Asia: Continuing Explorations. Routledge. pp. 158–. ISBN 978-1-136-81964-3.

- ^ "A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE TAY SON MOVEMENT (1771–1802)". EnglishRainbow. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ Tạ Chí Đại Trường 1973, p. 89

- ^ Thụy Khuê 2017, pp. 140–142

- ^ Tạ Chí Đại Trường 1973, p. 91

- ^ Hugh Dyson Walker (November 2012). East Asia: A New History. AuthorHouse. p. 298. ISBN 978-1-4772-6516-1.

- ^ a b Phan Khoang 2001, p. 508

- ^ a b Quốc sử quán triều Nguyễn 2007, p. 188

- ^ Tạ Chí Đại Trường 1973, pp. 110–111

- ^ Phan Khoang 2001, pp. 522–523

- ^ Phan Khoang 2001, p. 517

- ^ Huỳnh Minh 2006, p. 143

- ^ Quốc sử quán triều Nguyễn 2007, p. 195

- ^ Tạ Chí Đại Trường 1973, p. 124

- ^ Nguyễn Khắc Thuần (2005), Danh tướng Việt Nam, tập 3, Việt Nam: Nhà xuất bản Giáo dục, tr. 195

- ^ Tạ Chí Đại Trường 1973, pp. 178

- ^ Trần Trọng Kim 1971, pp. 111

- ^ Tạ Chí Đại Trường 1973, pp. 182–183

- ^ Tạ Chí Đại Trường 1973, pp. 183

- ^ Nguyễn Quang Trung Tiến 1999

- ^ Đặng Việt Thủy & Đặng Thành Trung 2008, p. 279

- ^ Phan Khoang 2001, p. 519

- ^ Sơn Nam 2009, pp. 54–55

- ^ Quốc sử quán triều Nguyễn 2007, p. 203

- ^ Trần Trọng Kim 1971, pp. 155

- ^ Quốc sử quán triều Nguyễn 2007, pp. 207–211

- ^ Kamm 1996, p. 83

- ^ Tarling 1999, pp. 245–246

- ^ Alexander Woodside (1971). Vietnam and the Chinese Model: A Comparative Study of Vietnamese and Chinese Government in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 120–. ISBN 978-0-674-93721-5.

- ^ Jacob Ramsay -Mandarins and Martyrs: The Church and the Nguyễn Dynasty in Early ... 2008 "This book is about the rise of anti-Catholic violence in early nineteenth-century Vietnam under the Nguyễn Dynasty, and the profound social and political changes it created in the decades preceding French colonialism."

- ^ Choi Byung Wook Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820–1841): 2004 Page 161 "These authors identify the creation of public land as the most important result of land measurement, and they judge that project to have been a significant achievement of the Nguyen dynasty, writing: 'Minh Mang clearly did not want southern ...'"

- ^ Jean-François Hubert (8 May 2012). The Art of Champa. Parkstone International. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-1-78042-964-9.

- ^ "The Raja Praong Ritual: A Memory of the Sea in Cham- Malay Relations". Cham Unesco. Archived from the original on 6 February 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ (Extracted from Truong Van Mon, "The Raja Praong Ritual: a Memory of the sea in Cham- Malay Relations", in Memory And Knowledge Of The Sea In South Asia, Institute of Ocean and Earth Sciences, University of Malaya, Monograph Series 3, pp, 97–111. International Seminar on Maritime Culture and Geopolitics & Workshop on Bajau Laut Music and Dance", Institute of Ocean and Earth Sciences and the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Malaya, 23-24/2008)

- ^ Dharma, Po. "The Uprisings of Katip Sumat and Ja Thak Wa (1833–1835)". Cham Today. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Choi Byung Wook (2004). Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820–1841): Central Policies and Local Response. SEAP Publications. pp. 141–. ISBN 978-0-87727-138-3.

- ^ Norman G. Owen (2005). The Emergence of Modern Southeast Asia: A New History. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 115–. ISBN 978-0-8248-2890-5.

- ^ Zottoli, Brian A. (2011). Reconceptualizing Southern Vietnamese Hi story from the 15th to 18th Centuries: Competition along the Coasts from Guangdong to Cambod (A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan). p. 14. Archived from the original on 29 January 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

{{cite thesis}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ A. Dirk Moses (1 January 2008). Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistance in World History. Berghahn Books. pp. 209–. ISBN 978-1-84545-452-4. Archived from the original on 2008.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help) - ^ Randall Peerenboom; Carole J. Petersen; Albert H.Y. Chen (27 September 2006). Human Rights in Asia: A Comparative Legal Study of Twelve Asian Jurisdictions, France and the USA. Routledge. pp. 474–. ISBN 978-1-134-23881-1.

- ^ "Vietnam-Champa Relations and the Malay-Islam Regional Network in the 17th–19th Centuries". Web.archive.org. 17 June 2004. Archived from the original on 17 June 2004. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Choi Byung Wook (2004). Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820–1841): Central Policies and Local Response. SEAP Publications. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-0-87727-138-3.

- ^ Choi Byung Wook (2004). Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820–1841): Central Policies and Local Response. SEAP Publications. pp. 136–. ISBN 978-0-87727-138-3.

- ^ Choi Byung Wook (2004). Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820–1841): Central Policies and Local Response. SEAP Publications. pp. 137–. ISBN 978-0-87727-138-3.

- ^ Nguyễn Đức Hiệp. Về lịch sử người Minh Hương và người Hoa ở Nam bộ. Văn hóa học, 21 February 2008. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ^ 蔣為文 (2013). "越南的明鄉人與華人移民的族群認同與本土化差異" (PDF). 台灣國際研究季刊 (in Chinese (Taiwan)). 9 (4). 國立成功大學越南研究中心: 8. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ Leo Suryadinata (1997). Ethnic Chinese as Southeast Asians. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9813055502. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- ^ "明鄉人". Chinese Encyclopedia (in Chinese (Taiwan)). Chinese Culture University. 1983. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ^ Alexander Woodside (1971). Vietnam and the Chinese Model: A Comparative Study of Vietnamese and Chinese Government in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-0-674-93721-5.

- ^ "Laos and Cambodia". Country Studies. U.S. Library of Congress.

- ^ Alexander Woodside (1971). Vietnam and the Chinese Model: A Comparative Study of Vietnamese and Chinese Government in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 134–. ISBN 978-0-674-93721-5.

- ^ Globalization: A View by Vietnamese Consumers Through Wedding Windows. ProQuest. 2008. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-0-549-68091-8.

- ^ "Angelasancartier.net". angelasancartier.net. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help) - ^ "#18 Transcultural Tradition of the Vietnamese Ao Dai". Beyondvictoriana.com. 14 March 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help) - ^ "Ao Dai – LoveToKnow". Fashion-hjistory.lovetoknow.com. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- ^ "The Ao Dai and I: A Personal Essay on Cultural Identity and Steampunk". Tor.com. 20 October 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help) - ^ Vietnam. Michelin Travel Publications. 2002. p. 200.

- ^ Gary Yia Lee; Nicholas Tapp (16 September 2010). Culture and Customs of the Hmong. ABC-CLIO. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-0-313-34527-2.

- ^ Anthony Reid (2 June 2015). A History of Southeast Asia: Critical Crossroads. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 285–. ISBN 978-0-631-17961-0.

- ^ Anthony Reid (9 May 1990). Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450–1680: The Lands Below the Winds. Yale University Press. pp. 90–. ISBN 978-0-300-04750-9.

- ^ A. Terry Rambo (2005). Searching for Vietnam: Selected Writings on Vietnamese Culture and Society. Kyoto University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-920901-05-9.

- ^ Jayne Werner; John K. Whitmore; George Dutton (21 August 2012). Sources of Vietnamese Tradition. Columbia University Press. pp. 295–. ISBN 978-0-231-51110-0.

- ^ Alexander Woodside (1971). Vietnam and the Chinese Model: A Comparative Study of Vietnamese and Chinese Government in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 117–. ISBN 978-0-674-93721-5.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "越南名儒李文馥-龙文,乡贤,名儒-龙文新闻网". Lwxww.cn. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- ^ John Gillespie; Albert H.Y. Chen (30 July 2010). Legal Reforms in China and Vietnam: A Comparison of Asian Communist Regimes. Taylor & Francis. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-0-203-85269-9.John Gillespie; Albert H.Y. Chen (13 September 2010). Legal Reforms in China and Vietnam: A Comparison of Asian Communist Regimes. Routledge. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-1-136-97843-2.John Gillespie; Albert H.Y. Chen (13 September 2010). Legal Reforms in China and Vietnam: A Comparison of Asian Communist Regimes. Routledge. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-1-136-97842-5.

- ^ Charles Holcombe (January 2001). The Genesis of East Asia: 221 B.C. – A.D. 907. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 41–. ISBN 978-0-8248-2465-5.

- ^ Pamela D. McElwee (2003). 'Lost worlds' or 'lost causes'?: biodiversity conservation, forest management, and rural life in Vietnam. Yale University. p. 67.Pamela D. McElwee (2003). 'Lost worlds' or 'lost causes'?: biodiversity conservation, forest management, and rural life in Vietnam. Yale University. p. 67.

- ^ Journal of Vietnamese Studies. University of California Press. 2006. p. 317.

- ^ Journal of Vietnamese Studies. University of California Press. 2006. p. 325.

- ^ Kelley, L. (2006). ""Confucianism" in Vietnam: A State of the Field Essay". Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 1 (1–2): 325. JSTOR 10.1525/vs.2006.1.1-2.314?seq=12.

- ^ ""Confucianism" in Vietnam: A State of the Field Essay". ResearchGate. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- ^ Kelley, Liam C. (1 February 2006). ""Confucianism" in Vietnam: A State of the Field Essay". Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 1 (1–2): 314–370. doi:10.1525/vs.2006.1.1-2.314. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Woodside; Kelley; Cooke (9 March 2016). "Q. How Confucian is/was Vietnam?". Cindyanguyen.wordpress.com. Retrieved 19 November 2017.