Apollo 16: Difference between revisions

Cassiopeia (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by Pizzadude1316 (talk) (HG) (3.4.4) |

→Particles and Fields Subsatellite PFS-2: The cited reference didn't support the original phrasing. Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 255: | Line 255: | ||

The Apollo 16 Particles and Fields Subsatellite (PFS-2) was a small satellite released into lunar orbit from the service module. Its principal objective was to measure charged particles and magnetic fields all around the Moon as the Moon orbited Earth, similar to its sister spacecraft, [[PFS-1]], released eight months earlier by Apollo 15. "The low orbits of both subsatellites were to be similar ellipses, ranging from {{convert|55|to|76|mi|km|abbr=off}} above the lunar surface."<ref name=nasa20061106>{{cite web |title=Bizarre Lunar Orbits |url=https://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2006/06nov_loworbit/ |last=Bell |first=Trudy E. |date=November 6, 2006 |editor-last=Phillips |editor-first=Tony |work=Science@NASA |publisher=NASA |accessdate=2012-12-09 |quote=''Lunar mascons make most low lunar orbits unstable ... As a satellite passes 50 or 60 miles overhead, the mascons pull it forward, back, left, right, or down, the exact direction and magnitude of the tugging depends on the satellite's trajectory. Absent any periodic boosts from onboard rockets to correct the orbit, most satellites released into low lunar orbits (under about 60 miles or 100 km) will eventually crash into the Moon. ... [There are] a number of 'frozen orbits' where a spacecraft can stay in a low lunar orbit indefinitely. They occur at four inclinations: 27°, 50°, 76°, and 86°"—the last one being nearly over the lunar poles. The orbit of the relatively long-lived Apollo 15 subsatellite [[PFS-1]] had an inclination of 28°, which turned out to be close to the inclination of one of the frozen orbits—but poor PFS-2 was cursed with an inclination of only 11°.''}}</ref> |

The Apollo 16 Particles and Fields Subsatellite (PFS-2) was a small satellite released into lunar orbit from the service module. Its principal objective was to measure charged particles and magnetic fields all around the Moon as the Moon orbited Earth, similar to its sister spacecraft, [[PFS-1]], released eight months earlier by Apollo 15. "The low orbits of both subsatellites were to be similar ellipses, ranging from {{convert|55|to|76|mi|km|abbr=off}} above the lunar surface."<ref name=nasa20061106>{{cite web |title=Bizarre Lunar Orbits |url=https://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2006/06nov_loworbit/ |last=Bell |first=Trudy E. |date=November 6, 2006 |editor-last=Phillips |editor-first=Tony |work=Science@NASA |publisher=NASA |accessdate=2012-12-09 |quote=''Lunar mascons make most low lunar orbits unstable ... As a satellite passes 50 or 60 miles overhead, the mascons pull it forward, back, left, right, or down, the exact direction and magnitude of the tugging depends on the satellite's trajectory. Absent any periodic boosts from onboard rockets to correct the orbit, most satellites released into low lunar orbits (under about 60 miles or 100 km) will eventually crash into the Moon. ... [There are] a number of 'frozen orbits' where a spacecraft can stay in a low lunar orbit indefinitely. They occur at four inclinations: 27°, 50°, 76°, and 86°"—the last one being nearly over the lunar poles. The orbit of the relatively long-lived Apollo 15 subsatellite [[PFS-1]] had an inclination of 28°, which turned out to be close to the inclination of one of the frozen orbits—but poor PFS-2 was cursed with an inclination of only 11°.''}}</ref> |

||

Instead, something unexpected happened. "The orbit of PFS-2 rapidly changed shape and distance from the Moon. In 2-1/2 weeks the satellite was swooping to within a hair-raising {{convert|6|mi|km}} of the lunar surface at closest approach. As the orbit kept changing, PFS-2 backed off again, until it seemed to be a safe 30 miles away. But not for long: inexorably, the subsatellite's orbit carried it back toward the Moon. And on May 29, 1972—only 35 days and 425 orbits after its release"—PFS-2 crashed into the Lunar surface.<ref name=nasa20061106/> |

|||

==Spacecraft locations== |

==Spacecraft locations== |

||

Revision as of 01:38, 24 March 2019

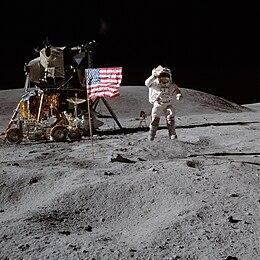

John Young on the Moon, with the Apollo Lunar Module and Lunar Roving Vehicle in the background | |

| Mission type | Manned lunar landing |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA[1] |

| COSPAR ID |

|

| SATCAT no. |

|

| Mission duration | 11 days, 1 hour, 51 minutes, 5 seconds |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft |

|

| Manufacturer |

|

| Launch mass | 107,226 pounds (48,637 kg) |

| Landing mass | 11,995 pounds (5,441 kg) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 3 |

| Members | |

| Callsign |

|

| EVAs | 1 in cislunar space to retrieve film cassettes |

| EVA duration | 1 h 23 min 42 s |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | April 16, 1972, 17:54:00 UTC |

| Rocket | Saturn V SA-511 |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39A |

| End of mission | |

| Recovered by | USS Ticonderoga |

| Landing date | April 27, 1972, 19:45:05 UTC |

| Landing site | South Pacific Ocean 0°43′S 156°13′W / 0.717°S 156.217°W |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Selenocentric |

| Periselene altitude | 20.2 kilometers (10.9 nmi) |

| Aposelene altitude | 108.3 kilometers (58.5 nmi) |

| Epoch | April 20, 1972, 00:27 UTC |

| Lunar orbiter | |

| Spacecraft component | Command and service module |

| Orbital insertion | April 19, 1972, 20:22:27 UTC |

| Orbital departure | April 25, 1972, 02:15:33 UTC |

| Orbits | 64 |

| Lunar lander | |

| Spacecraft component | Lunar module |

| Landing date | April 21, 1972, 02:23:35 UTC |

| Return launch | April 24, 1972, 01:25:47 UTC |

| Landing site | Descartes Highlands 8°58′23″S 15°30′01″E / 8.97301°S 15.50019°E |

| Sample mass | 95.71 kilograms (211.0 lb) |

| Surface EVAs | 3 |

| EVA duration |

|

| Lunar rover | |

| Distance driven | 26.7 kilometers (16.6 mi) |

| Docking with LM | |

| Docking date | April 16, 1972, 21:15:53 UTC |

| Undocking date | April 20, 1972, 18:07:31 UTC |

| Docking with LM Ascent Stage | |

| Docking date | April 24, 1972, 03:35:18 UTC |

| Undocking date | April 24, 1972, 20:54:12 UTC |

| Payload | |

| Mass |

|

Left to right: Mattingly, Young, Duke | |

Apollo 16 was the tenth manned mission in the United States Apollo space program, the fifth and penultimate to land on the Moon and the first to land in the lunar highlands. The second of the so-called "J missions," it was crewed by Commander John Young, Lunar Module Pilot Charles Duke and Command Module Pilot Ken Mattingly. Launched from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida at 12:54 PM EST on April 16, 1972, the mission lasted 11 days, 1 hour, and 51 minutes, and concluded at 2:45 PM EST on April 27.[2][3][4]

Young and Duke spent 71 hours—just under three days—on the lunar surface, during which they conducted three extra-vehicular activities or moonwalks, totaling 20 hours and 14 minutes. The pair drove the Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV), the second produced and used on the Moon, for 26.7 kilometers (16.6 mi). On the surface, Young and Duke collected 95.8 kilograms (211 lb) of lunar samples for return to Earth, while Command Module Pilot Ken Mattingly orbited in the command and service module (CSM) above to perform observations. Mattingly spent 126 hours and 64 revolutions in lunar orbit. After Young and Duke rejoined Mattingly in lunar orbit, the crew released a subsatellite from the service module (SM). During the return trip to Earth, Mattingly performed a one-hour spacewalk to retrieve several film cassettes from the exterior of the service module.[2][3]

Apollo 16's landing spot in the highlands was chosen to allow the astronauts to gather geologically older lunar material than the samples obtained in the first four landings, which were in or near lunar maria. Samples from the Descartes Formation and the Cayley Formation disproved a hypothesis that the formations were volcanic in origin.[5]

Crew

| Position[6] | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | John W. Young Fourth spaceflight | |

| Command Module Pilot | Thomas K. Mattingly II First spaceflight | |

| Lunar Module Pilot | Charles M. Duke Jr. Only spaceflight | |

Mattingly had originally been assigned to the prime crew of Apollo 13, but was exposed to rubella through Duke, at that time on the back-up crew for Apollo 13, who had caught it from one of his children. He never contracted the illness, but was nevertheless removed from the crew and replaced by his backup, Jack Swigert, three days before the launch.[7] Young, a captain in the United States Navy, had flown on three spaceflights prior to Apollo 16: Gemini 3, Gemini 10 and Apollo 10, which orbited the Moon.[8] One of 19 astronauts selected by NASA in April 1966, Duke had never flown in space before Apollo 16. He served on the support crew of Apollo 10 and was a capsule communicator (CAPCOM) for Apollo 11.[9]

Backup crew

| Position[6] | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Fred W. Haise Jr. | |

| Command Module Pilot | Stuart A. Roosa | |

| Lunar Module Pilot | Edgar D. Mitchell | |

Although not officially announced, the original backup crew consisted of Fred W. Haise (CDR), William R. Pogue (CMP) and Gerald P. Carr (LMP), who were targeted for the prime crew assignment on Apollo 19.[10][11] However, after the cancellations of Apollos 18 and 19 were finalized in September 1970 this crew would not rotate to a lunar mission as planned. Subsequently, Roosa and Mitchell were recycled to serve as members of the backup crew after returning from Apollo 14, while Pogue and Carr were reassigned to the Skylab program where they flew on Skylab 4.[12][13]

Support crew

- Anthony W. England[14]

- Karl G. Henize[15]

- Henry W. Hartsfield Jr.[16]

- Robert F. Overmyer[15]

- Donald H. Peterson[17]

Mission insignia

The insignia of Apollo 16 is dominated by a rendering of an American eagle and a red, white and blue shield, representing the people of the United States, over a gray background representing the lunar surface. Overlaying the shield is a gold NASA vector, orbiting the Moon. On its gold-outlined blue border, there are 16 stars, representing the mission number, and the names of the crew members: Young, Mattingly, Duke.[18] The insignia was designed from ideas originally submitted by the crew of the mission.[19]

Planning and training

Landing site selection

Apollo 16 was the second of the Apollo type J missions, featuring the use of the Lunar Roving Vehicle, increased scientific capability, and lunar surface stays of three days.[2] As Apollo 16 was the penultimate mission in the Apollo program and there was no new hardware or procedures to test on the lunar surface, the last two missions (the other being Apollo 17) presented opportunities for astronauts to clear up some uncertainties in understanding the Moon's properties. Although previous Apollo expeditions, including Apollo 14 and Apollo 15, obtained samples of pre-mare lunar material, before lava began to upwell from the Moon's interior and flood the low areas and basins, none had actually visited the lunar highlands.[20]

Apollo 14 had visited and sampled a ridge of material that had been ejected by the impact that created the Mare Imbrium impact basin. Likewise, Apollo 15 had also sampled material in the region of Imbrium, visiting the basin's edge. There remained the possibility, because the Apollo 14 and Apollo 15 landing sites were closely associated with the Imbrium basin, that different geologic processes were prevalent in areas of the lunar highlands far from Mare Imbrium. Several members of the scientific community remarked that the central lunar highlands resembled regions on Earth that were created by volcanic processes and hypothesized the same might be true on the Moon. They had hoped that scientific output from the Apollo 16 mission would provide an answer.[20]

Two locations on the Moon were given primary consideration for exploration by the Apollo 16 expedition: the Descartes Highlands region west of Mare Nectaris and the crater Alphonsus. At Descartes, the Cayley and Descartes formations were the primary areas of interest in that scientists suspected, based on telescopic and orbital imagery, that the terrain found there was formed by magma more viscous than that which formed the lunar maria. The Cayley Formation's age was approximated to be about the same as Mare Imbrium based on the local frequency of impact craters. The considerable distance between the Descartes site and previous Apollo landing sites would be beneficial for the network of geophysical instruments,[21] portions of which were deployed on each Apollo expedition beginning with Apollo 12.[5]

At the Alphonsus, three scientific objectives were determined to be of primary interest and paramount importance: the possibility of old, pre-Imbrium impact material from within the crater's wall, the composition of the crater's interior and the possibility of past volcanic activity on the floor of the crater at several smaller "dark halo" craters. Geologists feared, however, that samples obtained from the crater might have been contaminated by the Imbrium impact, thus preventing Apollo 16 from obtaining samples of pre-Imbrium material. There also remained the distinct possibility that this objective had already been satisfied by the Apollo 14 and Apollo 15 missions, as the Apollo 14 samples had not yet been completely analyzed and samples from Apollo 15 had not yet been obtained.[5]

It was decided to target the Apollo 16 mission for the Descartes site. Following the decision, the Alphonsus site was considered the most likely candidate for Apollo 17, but was eventually rejected. With the assistance of orbital photography obtained on the Apollo 14 mission, the Descartes site was determined to be safe enough for a manned landing. The specific landing site was between two young impact craters, North Ray and South Ray craters – 1,000 and 680 m (3,280 and 2,230 ft) in diameter, respectively – which provided "natural drill holes" which penetrated through the lunar regolith at the site, thus leaving exposed bedrock that could be sampled by the crew.[5]

After selecting the landing site for Apollo 16, sampling the Descartes and Cayley formations, two geologic units of the lunar highlands, was determined by mission planners to be the primary sampling interest of the mission. It was these formations that the scientific community widely suspected were formed by lunar volcanism, but this hypothesis was proven incorrect by the composition of lunar samples from the mission.[5]

Training

In preparing for their mission, in addition to the usual Apollo spacecraft training, Young and Duke, along with backup commander Fred Haise, underwent an extensive geological training program that included several field trips to introduce them to concepts and techniques they would use in analyzing features and collecting samples on the lunar surface. During these trips, they visited and provided scientific descriptions of geologic features they were likely to encounter.[22][23][24] In July 1971, they visited Sudbury, Ontario, Canada for geology training exercises, the first time U.S. astronauts did so. Geologists chose the area because of a 60 mi (97 km) wide crater created about 1.8 billion years ago by a large meteorite.[25] The Sudbury Basin shows evidence of shatter cone geology familiarizing the Apollo crew with geologic evidence of a meteor impact. During the training exercises the astronauts did not wear space suits, but carried radio equipment to converse with each other and scientist-astronaut Anthony W. England, practicing procedures they would use on the lunar surface.[26]

In addition to the field geology training, Young and Duke also trained to use their EVA space suits, adapt to the reduced lunar gravity, collect samples, and drive the Lunar Roving Vehicle. They also received survival training and preparation for other technical aspects of the mission.[27]

Command Module Pilot Mattingly also received training in recognizing geological features from orbit by flying over the field areas in an airplane, and trained to operate the Scientific Instrument Module from lunar orbit.

Mission highlights

Launch and outbound trip

The launch of Apollo 16 was delayed one month from March 17 to April 16. This was the first launch delay in the Apollo program due to a technical problem. During the delay, the space suits, a spacecraft separation mechanism and batteries in the lunar module (LM) were modified and tested.[28] There were concerns that the explosive mechanism designed to separate the docking ring from the command module (CM) would not create enough pressure to completely sever the ring. This, along with a dexterity issue in Young's space suit and fluctuations in the capacity of the lunar module batteries, required investigation and trouble-shooting.[29] In January 1972, three months before the planned April launch date, a fuel tank in the command module was accidentally damaged during a routine test.[30] The rocket was returned to the Vertical Assembly Building (VAB) and the fuel tank replaced, and the rocket returned to the launch pad in February in time for the scheduled launch.[31]

The official mission countdown began on Monday, April 10, 1972, at 8:30 AM, six days before the launch. At this point the Saturn V rocket's three stages were powered up and drinking water was pumped into the spacecraft. As the countdown began, the crew of Apollo 16 was participating in final training exercises in anticipation of a launch on April 16. The astronauts underwent their final preflight physical examination on April 11.[32] On April 15, liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants were pumped into the spacecraft, while the astronauts rested in anticipation of their launch the next day.[33]

The Apollo 16 mission launched from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida at 12:54 PM EST on April 16, 1972.[34] The launch was nominal; the crew experienced vibration similar to that of previous crews. The first and second stages of the Saturn V rocket performed nominally; the spacecraft entered orbit around Earth just under 12 minutes after lift-off. After reaching orbit, the crew spent time adapting to the zero-gravity environment and preparing the spacecraft for Trans Lunar Injection (TLI), the burn of the third-stage rocket that would propel them to the Moon. In Earth orbit, the crew faced minor technical issues, including a potential problem with the environmental control system and the S-IVB third stage's attitude control system, but eventually resolved or compensated for them as they prepared to depart towards the Moon. After two orbits, the rocket's third stage reignited for just over five minutes, propelling the craft towards the Moon at about 22,000 mph (35,000 km/h).[35] Six minutes after the burn of the S-IVB, the command and service module, containing the crew, separated from the rocket and traveled for 15 m (49 ft) before turning around and retrieving the lunar module from inside the expended rocket stage. The maneuver, known as transposition, went smoothly and the LM was extracted from the S-IVB.[36][37] Following transposition and docking, the crew noticed the exterior surface of the lunar module was giving off particles from a spot where the LM's skin appeared torn or shredded; at one point, Duke estimated they were seeing about five to ten particles per second. The crew entered the lunar module through the docking tunnel connecting it with the command module to inspect its systems, at which time they did not spot any major issues. Once on course towards the Moon, the crew put the spacecraft into a rotisserie "barbecue" mode in which the craft rotated along its long axis three times per hour to ensure even heat distribution about the spacecraft from the Sun. After further preparing the craft for the voyage, the crew began the first sleep period of the mission just under 15 hours after launch.[38]

By the time Mission Control issued the wake-up call to the crew for flight day two, the spacecraft was about 98,000 nautical miles (181,000 km) away from the Earth, traveling at about 5,322 ft/s (1,622 m/s). As it was not due to arrive in lunar orbit until flight day four,[39] flight days two and three were largely preparatory days, consisting of spacecraft maintenance and scientific research. On day two, the crew performed an electrophoresis experiment, also performed on Apollo 14, in which they attempted to prove the higher purity of particle migrations in the zero-gravity environment. The remainder of day two included a two-second mid-course correction burn performed by the CSM's service propulsion system engine to tweak the spacecraft's trajectory. Later in the day, the astronauts entered the lunar module for the second time in the mission to further inspect the landing craft's systems. The crew reported they had observed additional paint peeling from a portion of the LM's outer aluminum skin. Despite this, the crew discovered that the spacecraft's systems were performing nominally. Following the LM inspection, the crew reviewed checklists and procedures for the following days in anticipation of their arrival and the Lunar Orbit Insertion burn. Command Module Pilot Mattingly reported a "gimbal lock" warning light, indicating the craft was not reporting an attitude. Mattingly alleviated this by realigning the guidance system using the Sun and Moon. At the end of day two, Apollo 16 was about 140,000 nautical miles (260,000 km) away from Earth.[40]

At the beginning of day three, the spacecraft was about 157,000 nautical miles (291,000 km) away from the Earth. The velocity of the craft steadily decreased, as it had not yet reached the lunar sphere of gravitational influence. The early part of day three was largely housekeeping, spacecraft maintenance and exchanging status reports with Mission Control in Houston. The crew performed the Apollo light flash experiment, or ALFMED, to investigate "light flashes" that were seen by the astronauts when the spacecraft was dark, regardless of whether or not their eyes were open, on Apollo lunar flights. This was thought to be caused by the penetration of the eye by cosmic ray particles.[41][42] During the second half of the day, Young and Duke again entered the lunar module to power it up and check its systems, and perform housekeeping tasks in preparation for lunar landing. The systems were found to be functioning as expected. Following this, the crew donned their space suits and rehearsed procedures that would be used on landing day. Just before the end of flight day three at 59 hours, 19 minutes, 45 seconds after liftoff, while 178,673 nautical miles (330,902 km) from the Earth and 33,821 nautical miles (62,636 km) from the Moon, the spacecraft's velocity began increasing as it accelerated towards the Moon after entering the lunar sphere of influence.[43]

After waking up on flight day four, the crew began preparations for the maneuver that would brake the spacecraft into orbit around the Moon, or lunar orbit insertion.[39] At a distance of 11,142 nautical miles (20,635 km) from the Moon, the scientific instrument module (SIM) bay cover was jettisoned. At just over 74 hours into the mission, the spacecraft passed behind the Moon, losing direct contact with Mission Control. While over the far side of the Moon, the CSM's service propulsion system engine burned for 6 minutes and 15 seconds, braking the spacecraft into an orbit around the Moon with a low point (pericynthion) of 58.3 and a high point (apocynthion) of 170.4 nautical miles (108.0 and 315.6 km, respectively).[44] After entering lunar orbit, the crew began preparations for the Descent Orbit Insertion (DOI) maneuver to further modify the spacecraft's orbital trajectory. The maneuver was successful, decreasing the craft's pericynthion to 10.7 nautical miles (19.8 km). The remainder of flight day four was spent making observations and preparing for activation of the lunar module, undocking, and landing the next day.[45]

Lunar surface

The crew continued preparing for lunar module activation and undocking shortly after waking up to begin flight day five. The boom that extended the mass spectrometer out from the CSM's scientific instruments bay was stuck in a semi-deployed position. It was decided that Young and Duke would visually inspect the boom after undocking from the CSM in the LM. They entered the LM for activation and checkout of the spacecraft's systems. Despite entering the LM 40 minutes ahead of schedule, they completed preparations only 10 minutes early due to numerous delays in the process.[37] With the preparations finished, they undocked in the LM Orion from Mattingly in the CSM Casper 96 hours, 13 minutes, 13 seconds into the mission.[46] For the rest of the two crafts' passes over the near side of the Moon, Mattingly prepared to shift Casper to a circular orbit while Young and Duke prepared Orion for the descent to the lunar surface. At this point, during tests of the CSM's steerable rocket engine in preparation for the burn to modify the craft's orbit, a malfunction occurred in the engine's backup system. According to mission rules, Orion would have then re-docked with Casper, in case Mission Control decided to abort the landing and use the lunar module's engines for the return trip to Earth. After several hours of analysis, however, mission controllers determined that the malfunction could be worked around and Young and Duke could proceed with the landing.[20] As a result of this, powered descent to the lunar surface began about six hours behind schedule. Because of the delay, Young and Duke began their descent to the surface at an altitude higher than that of any previous mission, at 20.1 kilometers (10.9 nmi). At an altitude of about 4,000 m (13,000 ft), Young was able to view the landing site in its entirety. Throttle-down of the LM's landing engine occurred on time and the spacecraft tilted forward to its landing orientation at an altitude of 2,200 m (7,200 ft). The LM landed 270 m (890 ft) north and 60 m (200 ft) west of the planned landing site at 104 hours, 29 minutes, and 35 seconds into the mission, at 2:23:35 UTC on April 21.[37][47]

After landing, Young and Duke began powering down some of the LM's systems to conserve battery power. Upon completing their initial adjustments, the pair configured Orion for their three-day stay on the lunar surface, removed their space suits and took initial geological observations of the immediate landing site. They then settled down for their first meal on the surface. After eating, they configured the cabin for their first sleep period on the Moon.[48][49] The landing delay caused by the malfunction in the CSM's main engine necessitated significant modifications to the mission schedule. Apollo 16 would spend one less day in lunar orbit after surface exploration had been completed to afford the crew contingency time to compensate for any further problems and to conserve expendables. In order to improve Young's and Duke's sleep schedule, the third and final moonwalk of the mission was trimmed from seven hours to five.[37]

The next morning, flight day five, Young and Duke ate breakfast and began preparations for the first extra-vehicular activity (EVA), or moonwalk.[50][51] After the pair donned and pressurized their space suits and depressurized the lunar module cabin, Young climbed out onto the "porch" of the LM, a small platform above the ladder. Duke handed Young a jettison bag full of trash to dispose of on the surface.[52] Young then lowered the equipment transfer bag (ETB), containing equipment for use during the EVA, to the surface. Young descended the ladder and, upon setting foot on the lunar surface, became the ninth human to walk on the Moon.[37] Upon stepping onto the surface, Young expressed his sentiments about being there: "There you are: Mysterious and Unknown Descartes. Highland plains. Apollo 16 is gonna change your image. I'm sure glad they got ol' Brer Rabbit, here, back in the briar patch where he belongs."[52] Duke soon descended the ladder and joined Young on the surface, becoming the tenth and youngest human to walk on the Moon, at age 36. After setting foot on the lunar surface, Duke expressed his excitement, commenting: "Fantastic! Oh, that first foot on the lunar surface is super, Tony!"[52] The pair's first task of the moonwalk was to unload the Lunar Roving Vehicle, the Far Ultraviolet Camera/Spectrograph (UVC),[53] and other equipment, from the lunar module. This was done without problems. On first driving the lunar rover, Young discovered that the rear steering was not working. He alerted Mission Control to the problem before setting up the television camera and planting the flag of the United States with Duke.

The day's next task was to deploy the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP); while they were parking the lunar rover, on which the TV camera was mounted, to observe the deployment, the rear steering began functioning without explanation. While deploying a heat-flow experiment (that had burned up with the lunar module Aquarius on Apollo 13 and had been attempted with limited success on Apollo 15), a cable was inadvertently snapped after getting caught around Young's foot. After ALSEP deployment, they collected samples in the vicinity. About four hours after the beginning of EVA-1, they mounted the lunar rover and drove to the first geologic stop, Plum Crater, a 36 m-wide (118 ft) crater on the rim of Flag crater, about 240 m (790 ft) across. There, at a distance of 1.4 km (0.87 mi) from the LM, they sampled material from the vicinity of Flag Crater, which scientists believed penetrated through the upper regolith layer to the underlying Cayley Formation. It was there that Duke retrieved, at the request of Mission Control, the largest rock returned by an Apollo mission, a breccia nicknamed Big Muley after mission geology principal investigator William R. Muehlberger.[54][55] The next stop of the day was Buster Crater, about 1.6 km (0.99 mi) from the LM. There, Duke took pictures of Stone Mountain and South Ray Crater while Young deployed a magnetic field experiment.[56] At that point, scientists began to reconsider their pre-mission hypothesis that Descartes had been the setting of ancient volcanic activity, as the two astronauts had yet to find any volcanic material. Following their stop at Buster, Young did a demonstration drive of the lunar rover while Duke filmed with a 16 mm movie camera.[57] After completing more tasks at the ALSEP, they returned to the LM to close out the moonwalk. They reentered the LM 7 hours, 6 minutes, and 56 seconds after the start of the EVA. Once inside, they pressurized the LM cabin, went through a half-hour briefing with scientists in Mission Control, and configured the cabin for the sleep period.[54][58][59]

Shortly after waking up on the morning of flight day six three and a half minutes early, they discussed with Mission Control in Houston the day's timeline of events.[60][61] The second lunar excursion's primary objective was to visit Stone Mountain to climb up the slope of about 20 degrees to reach a cluster of five craters known as "Cinco Craters." After preparations for the day's moonwalk were completed, the astronauts climbed out of the lunar module. After departing the immediate landing site in the lunar rover, they arrived at the day's first destination, the Cinco craters, 3.8 km (2.4 mi) from the LM. At 152 m (499 ft) above the valley floor, the pair were at the highest elevation above the LM of any Apollo mission. After marveling at the view (including South Ray) from the side of Stone Mountain, which Duke described as "spectacular,"[62] the astronauts gathered samples in the vicinity.[54] After spending 54 minutes on the slope, they climbed aboard the lunar rover en route to the day's second stop, station five, a crater 20 m (66 ft) across. There, they hoped to find Descartes material that had not been contaminated by ejecta from South Ray Crater, a large crater south of the landing site. The samples they collected there, although their origin is still not certain, are, according to geologist Don Wilhelms, "a reasonable bet to be Descartes."[54] The next stop, station six, was a 10 m-wide (33 ft) blocky crater, where the astronauts believed they could sample the Cayley Formation as evidenced by the firmer soil found there. Bypassing station seven to save time, they arrived at station eight on the lower flank of Stone Mountain, where they sampled material on a ray from South Ray Crater for about an hour. There, they collected black and white breccias and smaller, crystalline rocks rich in plagioclase. At station nine, an area known as the "Vacant Lot,"[63] which was believed to be free of ejecta from South Ray, they spent about 40 minutes gathering samples. Twenty-five minutes after departing station nine, they arrived at the final stop of the day, halfway between the ALSEP site and the LM. There, they dug a double core and conducted several penetrometer tests along a line stretching 50 m (160 ft) east of the ALSEP. At the request of Young and Duke, the moonwalk was extended by ten minutes. After returning to the LM to wrap up the second lunar excursion, they climbed back inside the landing craft's cabin, sealing and pressurizing the interior after 7 hours, 23 minutes, and 26 seconds of EVA time, breaking a record that had been set on Apollo 15.[54][64] After eating a meal and proceeding with a debriefing on the day's activities with Mission Control, they reconfigured the LM cabin and prepared for the sleep period.[65]

Flight day seven was their third and final day on the lunar surface, returning to orbit to rejoin Mattingly in the CSM following the day's moonwalk. During the third and final lunar excursion, they were to explore North Ray Crater, the largest of any of the craters any Apollo expedition had visited. After exiting Orion, the pair drove the lunar rover 0.8 km (0.50 mi) away from the LM before adjusting their heading to travel 1.4 km (0.87 mi) to North Ray Crater. The drive was smoother than that of the previous day, as the craters were shallower and boulders were less abundant north of the immediate landing site. After passing Palmetto crater, boulders gradually became larger and more abundant as they approached North Ray in the lunar rover. Upon arriving at the rim of North Ray crater, they were 4.4 km (2.7 mi) away from the LM. After their arrival, the duo took photographs of the 1 km (0.62 mi) wide and 230 m (750 ft) deep crater. They visited a large boulder, taller than a four-story building, which became known as 'House Rock'. Samples obtained from this boulder delivered the final blow to the pre-mission volcanic hypothesis, proving it incorrect. House Rock had numerous bullet hole-like marks where micrometeoroids from space had impacted the rock. About 1 hour and 22 minutes after arriving, they departed for station 13, a large boulder field about 0.5 km (0.31 mi) from North Ray. On the way, they set a lunar speed record, traveling at an estimated 17.1 kilometers per hour (10.6 mph) downhill. They arrived at a 3 m (9.8 ft) high boulder, which they called 'Shadow Rock'. Here, they sampled permanently shadowed soil. During this time, Mattingly was preparing the CSM in anticipation of their return approximately six hours later. After three hours and six minutes, they returned to the LM, where they completed several experiments and offloaded the rover. A short distance from the LM, Duke placed a photograph of his family and a United States Air Force commemorative medallion on the surface.[54] Young drove the rover to a point about 90 m (300 ft) east of the LM, known as the 'VIP site,' so its television camera, controlled remotely by Mission Control, could observe Apollo 16's liftoff from the Moon. They then reentered the LM after a 5-hour and 40 minute final excursion.[67] After pressurizing the LM cabin, the crew began preparing to return to lunar orbit.[68]

Return to Earth

Eight minutes before departing the lunar surface, CAPCOM James Irwin notified Young and Duke from Mission Control that they were go for liftoff. Two minutes before launch, they activated the "Master Arm" switch and then the "Abort Stage" button, after which they awaited ignition of Orion’s ascent stage engine. When the ascent stage ignited, small explosive charges severed the ascent stage from the descent stage and cables connecting the two were severed by a guillotine-like mechanism. Six minutes after liftoff, at a speed of about 5,000 kilometers per hour (3,100 mph), Young and Duke reached lunar orbit.[54][69] Young and Duke successfully rendezvoused and re-docked with Mattingly in the CSM. To minimize the transfer of lunar dust from the LM cabin into the CSM, Young and Duke cleaned the cabin before opening the hatch separating the two spacecraft. After opening the hatch and reuniting with Mattingly, the crew transferred the samples Young and Duke had collected on the surface into the CSM for transfer to Earth. After transfers were completed, the crew would sleep before jettisoning the empty lunar module ascent stage the next day, when it was to be crashed intentionally into the lunar surface.[37]

The next day, after final checks were completed, the expended LM ascent stage was jettisoned.[70] Because of a failure by the crew to activate a certain switch in the LM before sealing it off, it initially tumbled after separation and did not execute the rocket burn necessary for the craft's intentional de-orbit. The ascent stage eventually crashed into the lunar surface nearly a year after the mission. The crew's next task, after jettisoning the lunar module ascent stage, was to release a subsatellite into lunar orbit from the CSM's scientific instrument bay. The burn to alter the CSM's orbit to that desired for the subsatellite had been cancelled; as a result, the subsatellite lasted half of its anticipated lifetime. Just under five hours later, on the CSM's 65th orbit around the Moon, its service propulsion system main engine was reignited to propel the craft on a trajectory that would return it to Earth. The SPS engine performed the burn flawlessly despite the malfunction that had delayed the lunar landing several days before.[37][70]

At a distance of about 170,000 nautical miles (310,000 km) from Earth, Mattingly performed a "deep-space" extra-vehicular activity, or spacewalk, during which he retrieved several film cassettes from the CSM's SIM bay. While outside the spacecraft, Mattingly set up a biological experiment, the Microbial Ecology Evaluation Device (MEED).[71] The MEED experiment was only performed on Apollo 16.[72] The crew carried out various housekeeping and maintenance tasks aboard the spacecraft and ate a meal before concluding the day.[71]

The penultimate day of the flight was largely spent performing experiments, aside from a twenty-minute press conference during the second half of the day. During the press conference, the astronauts answered questions pertaining to several technical and non-technical aspects of the mission prepared and listed by priority at the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston by journalists covering the flight. In addition to numerous housekeeping tasks, the astronauts prepared the spacecraft for its atmospheric reentry the next day. At the end of the crew's final full day in space, the spacecraft was approximately 77,000 nautical miles (143,000 km) from Earth and closing at a rate of about 7,000 feet per second (2,100 m/s).[73][74]

When the wake-up call was issued to the crew for their final day in space by CAPCOM Tony England, it was about 45,000 nautical miles (83,000 km) out from Earth, traveling just over 9,000 ft/s (2,700 m/s). Just over three hours before splashdown in the Pacific Ocean, the crew performed a final course correction burn, changing their velocity by 1.4 ft/s (0.43 m/s). Approximately ten minutes before reentry into Earth's atmosphere, the cone-shaped command module containing the three crewmembers separated from the service module, which would burn up during reentry. At 265 hours and 37 minutes into the mission, at a velocity of about 36,000 ft/s (11,000 m/s), Apollo 16 began atmospheric reentry. At its maximum, the temperature of the heat shield was between 4,000 and 4,500 °F (2,200 and 2,480 °C). After successful parachute deployment and less than 14 minutes after reentry began, the command module splashed down in the Pacific Ocean 350 km (220 mi) southeast of the island of Kiritimati (or "Christmas Island"), 290 hours, 37 minutes, 6 seconds after liftoff. The spacecraft and its crew was retrieved by the USS Ticonderoga. They were safely aboard the Ticonderoga 37 minutes after splashdown.[37][75]

Particles and Fields Subsatellite PFS-2

The Apollo 16 Particles and Fields Subsatellite (PFS-2) was a small satellite released into lunar orbit from the service module. Its principal objective was to measure charged particles and magnetic fields all around the Moon as the Moon orbited Earth, similar to its sister spacecraft, PFS-1, released eight months earlier by Apollo 15. "The low orbits of both subsatellites were to be similar ellipses, ranging from 55 to 76 miles (89 to 122 kilometres) above the lunar surface."[76]

Instead, something unexpected happened. "The orbit of PFS-2 rapidly changed shape and distance from the Moon. In 2-1/2 weeks the satellite was swooping to within a hair-raising 6 miles (9.7 km) of the lunar surface at closest approach. As the orbit kept changing, PFS-2 backed off again, until it seemed to be a safe 30 miles away. But not for long: inexorably, the subsatellite's orbit carried it back toward the Moon. And on May 29, 1972—only 35 days and 425 orbits after its release"—PFS-2 crashed into the Lunar surface.[76]

Spacecraft locations

The aircraft carrier USS Ticonderoga delivered the Apollo 16 command module to the North Island Naval Air Station, near San Diego, California, on Friday, May 5, 1972. On Monday, May 8, 1972, ground service equipment being used to empty the residual toxic reaction control system fuel in the command module tanks exploded in a Naval Air Station hangar. Forty-six people were sent to the hospital for 24 to 48 hours observation, most suffering from inhalation of toxic fumes. Most seriously injured was a technician who suffered a fractured kneecap when the GSE cart overturned on him. A hole was blown in the hangar roof 250 feet above; about 40 windows in the hangar were shattered. The command module suffered a three-inch gash in one panel.[77][78][79]

The Apollo 16 command module Casper is on display at the U.S. Space & Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama. The lunar module ascent stage separated 24 April 1972 but a loss of attitude control rendered it out of control. It orbited the Moon for about a year. Its impact site remains unknown.[80] The S-IVB was deliberately crashed into the Moon. However, due to a communication failure before impact the exact location was unknown until January 2016, when it was discovered within Mare Insularum by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, approximately 160 mi (260 km) southwest of Copernicus Crater.[37][80][81]

Duke donated some flown items, including a lunar map, to Kennesaw State University in Kennesaw, Georgia. He left two items on the Moon, both of which he photographed. The most famous is a plastic-encased photo portrait of his family (NASA Photo AS16-117-18841[82]). The reverse of the photo is signed by Duke's family and bears this message: "This is the family of Astronaut Duke from Planet Earth. Landed on the Moon, April 1972." The other item was a commemorative medal issued by the United States Air Force, which was celebrating its 25th anniversary in 1972. He took two medals, leaving one on the Moon and donating the other to the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base museum.[83]

In 2006, shortly after Hurricane Ernesto affected Bath, North Carolina, eleven-year-old Kevin Schanze discovered a piece of metal debris on the ground near his beach home. Schanze and a friend discovered a "stamp" on the 36-inch (91 cm) flat metal sheet, which upon further inspection turned out to be a faded copy of the Apollo 16 mission insignia. NASA later confirmed the object to be a piece of the first stage of the Saturn V rocket that launched Apollo 16 into space. In July 2011, after returning the piece of debris at NASA's request, 16-year-old Schanze was given an all-access tour of the Kennedy Space Center and VIP seating for the launch of STS-135, the final mission of the Space Shuttle program.[84]

See also

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- ^ Richard W. Orloff. "Apollo by the Numbers: A Statistical Reference (SP-4029)". NASA.

- ^ a b c Wade, Mark. "Apollo 16". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 11 November 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Apollo 16 Mission Overview". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ "Apollo 16 (AS-511) Landing in the Descartes highlands". The Apollo Program. Washington, D.C.: National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "Landing Site Overview". Apollo 16 Mission. Lunar and Planetary Institute. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Apollo 16 Crew". The Apollo Program. Washington, D.C.: National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ Atkinson, Nancy (12 April 2010). "13 Things That Saved Apollo 13, Part 3: Charlie Duke's Measles". Universe Today. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ "Crew Set For Apollo 16 Moon Trip". Toledo Blade. Associated Press. 4 March 1971. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Charles Duke". NASA. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ Slayton & Cassutt 1994, p. 262

- ^ "Apollo 18 through 20 - The Cancelled Missions". NASA. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ Oard, Doug. "The Moonwalkers Who Could Have Been". University of Maryland. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: William Reid Pogue". NASA. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Anthony W. England". NASA. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Chariots for Apollo, Appendix B". NASA. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Henry W. Hartsfield". NASA. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Donald H. Peterson". NASA. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ "Apollo Mission Insignias". NASA. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ "0401439 - Apollo 16 Insignia". NASA. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ a b c "Descartes Surprise". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ Brzostowski and Brzostowski, pp 414-416

- ^ "Apollo Astronaut Training In Nevada". Nevada Aerospace Hall of Fame. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ "Apollo Geology Field Exercises". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Archived from the original on 17 October 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Apollo Geology Field Exercises" (PDF). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "New Evidence for the 1,850 My Sudbury Meteorite Impact" (PDF). GEOLOGI. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ Dickie, Allan (7 July 1971). "Astronauts training in Ont". The Leader-Post. Regina, Saskatchewan. The Canadian Press. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ Mason, Betsy (20 July 2011). "The Incredible Things NASA Did to Train Apollo Astronauts". Wired Science. Condé Nast Publications. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ "Apollo 16 landing postponed". The Miami News. 8 January 1972. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Moon Trip Delay Told". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Associated Press. 8 January 1972. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Apollo Launch Back To April 16 Date". Evening Independent. St. Petersburg, FL. Associated Press. 28 January 1972. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Apollo 16's Fuel Tank Won't Delay Mission". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. Associated Press. 3 February 1972. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Countdown Begins For Apollo 16 Moon Expedition". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Associated Press. 11 April 1972. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Apollo 16 Craft Fueled; Astronauts Take Rest". The Milwaukee Sentinel. Associated Press. 15 April 1972. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Apollo 16: Day One Part One: Launch and Reaching Earth Orbit". Apollo 16 Flight Journal. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Apollo 16: Day One Part Three: Second Earth Orbit and Translunar Injection". Apollo 16 Flight Journal. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Apollo 16: Day One Part Four: Transposition, Docking and Ejection". Apollo 16 Flight Journal. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Apollo 16 Flight Summary". Apollo Flight Journal. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Apollo 16: Day 1 Part 5: Settling into Translunar Coast". Apollo 16 Flight Journal. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Apollo 16: Day Four Part One - Arrival at the Moon". Apollo 16 Flight Journal. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Apollo 16: Day Two Part Two: LM Entry and Checks". Apollo 16 Flight Journal. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Apollo 16: Day Three Part One: ALFMED Experiment". Apollo 16 Flight Journal. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Apollo Light Flash Investigations (AP009)". Life Sciences Data Archive. NASA. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ "Apollo 16: Day Three Part Two: Lunar Module Activation and Checkout". Apollo 16 Flight Journal. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Apollo 16: Day Four Part Two; Lunar Orbit Insertion, Rev One and Rev Two". Apollo 16 Flight Journal. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Apollo 16: Day Four Part Three: Descent Orbit Insertion, Revs Three to Nine". Apollo 16 Flight Journal. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Apollo 16: Day Five Part Two: Lunar Module Undocking and Descent Preparation; Revs 11 and 12". Apollo 16 Flight Journal. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Landing at Descartes". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Post-Landing Activities". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Window Geology". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Wake-up for EVA-1". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Preparations for EVA-1". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ a b c "Back in the Briar Patch". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Experiment Operations During Apollo EVAs". Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science Directorate. NASA. Archived from the original on 20 February 2013. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Lindsay, Hamish. "Apollo 16" (Essay). Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Station 1 at Plum Crater". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Station 2 at Buster Crater". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Archived from the original on 25 October 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Grand Prix". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Archived from the original on 26 October 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "EVA-1 Closeout". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Archived from the original on 24 October 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Debrief and Goodnight". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Archived from the original on 21 October 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "EVA-2 Wake-up". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Archived from the original on 17 October 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Preparations for EVA-2". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Archived from the original on 21 October 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Geology Station 4 at the Stone Mountain Cincos". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Archived from the original on 25 October 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Geology Station 9". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ "EVA-2 Closeout". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Archived from the original on 26 October 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Post-EVA-2 Activities and Goodnight". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Traverse to North Ray Crater". nasa.gov.

- ^ "VIP Site". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Archived from the original on 26 October 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Post-EVA-3 Activities". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Return to Orbit". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Apollo 16: Day 9 Part 2 - LM Jettison and Trans Earth Injection". Apollo 16 Flight Journal. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Apollo 16: Day 10 Part 2 - EVA and Housekeeping". Apollo 16 Flight Journal. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Microbial Ecology Evaluation Device (MEED)". Life Sciences Data Archive. NASA. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Apollo 16: Day 11 Part One: Geology, Experiments and Guidance Fault Investigation". Apollo 16 Flight Journal. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ^ "Apollo 16: Day 11 Part Two: Press Conference, Experiments and House-Keeping". Apollo 16 Flight Journal. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ^ "Apollo 16: Day 12 - Entry and Splashdown". Apollo 16 Flight Journal. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ^ a b Bell, Trudy E. (November 6, 2006). Phillips, Tony (ed.). "Bizarre Lunar Orbits". Science@NASA. NASA. Retrieved 2012-12-09.

Lunar mascons make most low lunar orbits unstable ... As a satellite passes 50 or 60 miles overhead, the mascons pull it forward, back, left, right, or down, the exact direction and magnitude of the tugging depends on the satellite's trajectory. Absent any periodic boosts from onboard rockets to correct the orbit, most satellites released into low lunar orbits (under about 60 miles or 100 km) will eventually crash into the Moon. ... [There are] a number of 'frozen orbits' where a spacecraft can stay in a low lunar orbit indefinitely. They occur at four inclinations: 27°, 50°, 76°, and 86°"—the last one being nearly over the lunar poles. The orbit of the relatively long-lived Apollo 15 subsatellite PFS-1 had an inclination of 28°, which turned out to be close to the inclination of one of the frozen orbits—but poor PFS-2 was cursed with an inclination of only 11°.

- ^ "46 injured in Apollo 16 explosion". Lodi News-Sentinel. United Press International. 8 May 1972. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ "46 injured in Apollo 16 explosion (cont.)". Lodi News-Sentinel. United Press International. 8 May 1972. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ "Apollo blast: 46 hurt". The Sydney Morning Herald. Australian Associated Press-Reuters. 9 May 1972. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ a b "Apollo - Current Locations". NASA. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ Emspak, Jesse (4 January 2016). "Moon Mystery Solved! Apollo Rocket Impact Site Finally Found". Space. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ "AS16-117-18841.jpg". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ Swanson 1999, pp. 244–283

- ^ Holderness, Penn (8 July 2011). "Durham teen discovers piece of space history, lands VIP seat at final launch". WNCN. Raleigh, NC: Media General, Inc. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

Bibliography

- Brzostowski, M.A., and Brzostowski, A.C., Archiving the Apollo active seismic data, The Leading Edge, Society of Exploration Geophysicists, April 2009.

- Slayton, Donald K. "Deke"; Cassutt, Michael (1994). Deke! U.S. Manned Space: From Mercury to the Shuttle (1st ed.). New York: Forge. ISBN 0-312-85503-6. LCCN 94002463. OCLC 29845663.

- Swanson, Glen E., ed. (1999). "Charles M. Duke Jr.". "Before This Decade Is Out...": Personal Reflections on the Apollo Program. The NASA History Series. Foreword by Christopher C. Kraft Jr. Washington, D.C.: NASA. ISBN 0-16-050139-3. NASA SP-4223.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)

External links

- Apollo 16 Traverses, Lunar Photomap 78D2S2(25)

- Apollo 16 Press Kit – NASA, Release No. 72-64K, 6 April 1972

- On the Moon with Apollo 16: A guidebook to the Descartes Region by Gene Simmons, NASA, EP-95, 1972

- Apollo 16: "Nothing so hidden..." (Part 1) – NASA film on the Apollo 16 mission at the Internet Archive

- Apollo 16: "Nothing so hidden..." (Part 2) – NASA film on the Apollo 16 mission at the Internet Archive

- Apollo Lunar Surface VR Panoramas – QTVR panoramas at moonpans.com

- Apollo 16 Science Experiments at the Lunar and Planetary Institute

- Audio recording of Apollo 16 landing as recorded at the Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station

- Apollo launch and mission videos ApolloTV.net

- Interview with the Apollo 16 Astronauts (28 June 1972) from the Commonwealth Club of California Records at the Hoover Institution Archives

- "Apollo 16: Driving on the Moon" – Apollo 16 film footage of lunar rover at the Astronomy Picture of the Day, 29 January 2013

- Astronaut's Eye View of Apollo 16 Site, from LROC