British nuclear testing in the United States: Difference between revisions

Afernand74 (talk | contribs) NTS not defined in the lead + CTBT |

Theprussian (talk | contribs) re-wrote entire first paragraph as too informal. |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

Following the success of [[Operation Grapple]] in which the UK |

Following the success of [[Operation Grapple]] in which the UK developed a nuclear weapon capability, Britain launched negotiations with the US on a treaty under in which both could share information and material to design, test and maintain their nuclear weapons. This effort culminated in the [[1958 US–UK Mutual Defence Agreement]]. Which allowed the UK to test nuclear weapons in the United States. |

||

The United Kingdom signed the [[Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty]] in 1996 and ratified it in 1998, confirming the British commitment towards ending nuclear test explosions in the world. |

|||

== Background == |

== Background == |

||

Revision as of 00:15, 5 November 2018

| NTS series | |

|---|---|

Krakatau subcritical experiment being lowered into the floor of the tunnel of the U1a Complex at the Nevada Test Site. The cables extending from the hole will carry data from the experiment to recording instruments. | |

| Information | |

| Country | United Kingdom |

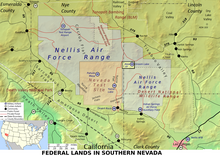

| Test site | NTS Area 19, 20, Pahute Mesa; NTS, Areas 1-4, 6-10, Yucca Flat |

| Period | 1962–1991 |

| Number of tests | 24 |

| Test type | underground shaft |

| Max. yield | 140 kilotonnes of TNT (590 TJ) |

| Test series chronology | |

Following the success of Operation Grapple in which the UK developed a nuclear weapon capability, Britain launched negotiations with the US on a treaty under in which both could share information and material to design, test and maintain their nuclear weapons. This effort culminated in the 1958 US–UK Mutual Defence Agreement. Which allowed the UK to test nuclear weapons in the United States.

Background

During the early part of the Second World War, Britain had a nuclear weapons project, codenamed Tube Alloys.[1] At the Quebec Conference in August 1943, the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill and the President of the United States, Franklin Roosevelt, signed the Quebec Agreement, which merged Tube Alloys with the American Manhattan Project to create a combined British, American and Canadian project. The British government had trusted that the United States would continue to share nuclear technology, which it regarded as a joint discovery, but the United States Atomic Energy Act of 1946 (McMahon Act) ended technical cooperation.[2] The British government feared that there might be a resurgence of United States isolationism, as had occurred after the First World War, in which case Britain might have to fight an aggressor alone,[3] and that Britain might lose its great power status and its influence in world affairs. It therefore restarted its own development effort,[4] now codenamed High Explosive Research.[5]

Implicit in the decision to develop atomic bombs was the need to test them.[6] Lacking open, thinly-populated areas, British officials considered locations overseas.[7] The preferred site was the American Pacific Proving Grounds. A request to use it was sent to the American Joint Chiefs of Staff, but no reply was received until October 1950, when the Americans turned down the request.[8] The uninhabited Monte Bello Islands in Australia were selected as an alternative.[9] Meanwhile, negotiations continued with the Americans. Oliver Franks, the British Ambassador to the United States, lodged a formal request on 2 August 1951 for use of the Nevada Test Site. This was looked upon favourably by the United States Secretary of State, Dean Acheson, and the chairman of the United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), Gordon Dean, but opposed by the Robert A. Lovett, the Deputy Secretary of Defense and Robert LeBaron, the Deputy Secretary of Defence for Atomic Energy Affairs. In view of security concerns, Lovett and LeBaron wanted the tests to be conducted by Americans, with British participation limited to selected British scientists. President Harry S. Truman endorsed this counterproposal on 24 September 1951.[10]

The Nevada Test Site would be cheaper than Monte Bello, although the cost would be paid in scarce dollars. Information gathered would have to be shared with the Americans, who would not share their own data. It would not be possible to test from a ship, and the political advantages in demonstrating that Britain could develop and test nuclear weapons without American assistance would be foregone,[9] and the Americans were under no obligation to make the test site available for subsequent tests. Also, as Lord Cherwell noted, an American test meant that "in the lamentable event of the bomb failing to detonate, we should look very foolish indeed."[11] In the end, Monte Bello was chosen, and the first British atomic bomb was tested there in Operation Hurricane on 3 October 1952.[12] The next British test series, Operation Totem, was conducted at Emu Field in South Australia, but at their conclusion, the British Government formally requested a permanent testing site from the Australian Government, which led to the agreement on the use of the Maralinga test site in August 1954.[13] The first of the British nuclear tests at Maralinga was held in September 1956.[14]

While British atomic bomb development represented an extraordinary scientific and technological achievement, hopes that the United States would be sufficiently impressed to restore the nuclear Special Relationship were dashed.[15] In November 1952, the United States conducted Ivy Mike, the first successful test of a true thermonuclear device or hydrogen bomb. Britain was therefore still several years behind in nuclear weapons technology.[16] The Defence Policy Committee, chaired by Churchill and consisting of the senior Cabinet members, considered the political and strategic implications, and concluded that "we must maintain and strengthen our position as a world power so that Her Majesty's Government can exercise a powerful influence in the counsels of the world."[17] In July 1954, Cabinet agreed to proceed with the development of thermonuclear weapons.[18]

The Australian government would not permit thermonuclear tests in Australia,[19] so Christmas Island in the Pacific was chosen for Operation Grapple, the testing of Britain's thermonuclear designs.[20] The Grapple tests were facilitated by the United States, which also claimed the island.[21] Although the initial tests were unsuccessful,[22] the Grapple X test on 8 November 1957 achieved the desired result, and Britain became only the third nation to develop thermonuclear weapon technology.[23][24] The British weapon makers had demonstrated all of the technologies that were needed to produce a megaton hydrogen bomb that weighed no more than 1 long ton (1.0 t) and was immune to premature detonation caused by nearby nuclear explosions. A one-year international moratorium commenced on 31 October 1958, and Britain never resumed atmospheric testing.[25]

British timing was good. The Soviet Union's launch of Sputnik 1 on 4 October 1957, came as a tremendous shock to the American public, and amid the widespread calls for action in response to the Sputnik crisis, officials in the United States and Britain seized an opportunity to mend the Anglo-American relationship that had been damaged by the Suez Crisis the year before.[26] The Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, wrote to President Dwight D. Eisenhower on 10 October, urging that the two countries pool their resources,[27] as Macmillan put it, "to meet the Soviet challenge on every front, military, political, economic and ideological."[28] The McMahon Act was amended to allow limited exchanges of nuclear weapons data and non-nuclear components of nuclear weapons to nations that had made substantial progress in the field. Only Britain qualified as a nation that had made substantial progress.[29] The bill was signed into law by Eisenhower on 2 July 1958,[30] and the 1958 US–UK Mutual Defence Agreement (MDA) was signed by Dulles and Samuel Hood, the British Minister in Washington, the following day,[31] and approved by the United States Congress on 30 July, thus restoring the Special Relationship.[32] Macmillan called it "the Great Prize".[33]

Testing

The MDA did not specifically address British nuclear testing at the Nevada Test Site (NTS), but it did provide a high-level framework for it to occur. The prospect was raised by the British Ambassador to the United States, Sir Roger Makins, at a meeting with the Chairman of the AEC, Glenn T. Seaborg, and Sir William Penney, the head of nuclear weapons development at the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA). On 3 November 1961, Macmillan wrote to President John F. Kennedy requesting the use of the Nevada Test Site for the testing of Super Octopus, a British kiloton warhead intended for use with the American Skybolt missile that was of great interest to weapon designers on both sides of the Atlantic. The response was positive, and on 8 February 1962, Seaborg announced, specifically referencing the MDA, that there would be a UK nuclear test at the NTS.[34][35] This developed into a procedure for approval of a British nuclear test. The director of the British Atomic Weapons Research Establishment (AWRE) would lodge a request with the chairman of the AEC, who would then make a recommendation to the president through the Secretary of State and the Secretary of Defence. Every test had to be approved by the president and the National Security Council.[36]

A Joint Working Group (JOWOG) was set up to coordinate the British tests. Test safety and containment requirements remained a US Federal responsibility. The JOWOG therefore decided that the UK would provide the test device and diagnostics package, while the US would provide everything else, including the test canister and the data cables leading from it to the trailers with US recording equipment. This threw up issues regarding the interface between the British diagnostics package and the American recording equipment. There were also issues related to procedures, particularly with regard to the testing of electronic and mechanical devices. A further complicating factor was that the US had two rival nuclear weapons laboratories, the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), with different procedures.[37]

For the first test, E. R. Drake Seager from the AWRE was designated the trial superintendent and Robert Campbell from LANL was designated the test director, these being the styles of the heads of the British and American teams. The test, codenamed Pampas, was conducted on 1 March 1962. It was Britain's first underground test.[37] The new Super Octopus implosion system worked but the overall result was disappointing. The RO.106 (Tony) warhead was based on the American Tsetse warhead, but used a different, safer but less powerful conventional explosive, EDC11. The result was that the yield was less than Tsetse, and too small to be used as the primary in the Skybolt warhead. A follow-up test of what became the basis for the WE.177 design codenamed Tendrac therefore took place on 7 December 1962, and was judged a success.[35] Tim subcritical tests and Vixen safety tests related to WE.177 were conducted at Maralinga in March and April 1963,[38] but four more British safety tests were conducted out at the NTS Tonopah Test Range as part of Operation Roller Coaster: Double Tracks on 15 May 1963, Clean Slate 1 on 25 May 1963, Clean Slate 2 on 31 May 1963 and Clean Slate 3 on 9 June 1963.[37][39] The Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, which went into effect on 10 October 1963, banned atmospheric nuclear testing, and the Maralinga range was closed for good in 1967.[37][38]

The Polaris Sales Agreement, which was signed in Washington, DC, on 6 April 1963,[40] meant that a new warhead was required. The Skybolt warhead tested in Tendrac had to be redesigned with a Re-Entry System (RES) that could be fitted to a Polaris missile, at an estimated cost of between £30 million and £40 million. The alternative was to make a British copy of the W58. While the AWRE was familiar with the W47 warhead used in the A2 Polaris missile, it knew nothing of the W58 used in the A3 which the British government had decided to buy. A presidential determination was required to release information on the W58 under the MDA, but with this in hand, a mission led by John Challens, the Chief of Warhead Development at the AWRE, visited the LLNL from 22 to 24 January 1963, and was shown details of the W58.[41] However a carbon copy of the American design was not possible, as the British used a different conventional explosive, and British fissile material was of a different composition of isotopes of plutonium. A new warhead was designed, with a fission primary codenamed Katie and a fusion secondary codenamed Reggie. The whole warhead was given the designation ET.317.[42]

A new test series was required, which was conducted with the LANL. The first was Whetstone Commorant on 17 July 1964. It was followed by Whetstone Courser on 25 September. The latter used an ET.317 Katie, but with 0.45 kg less plutonium. The test was a failure due to a fault in the American-made neutron initiators, and had to be repeated in the Flintlock Charcoal test on 10 September 1965. This test had to be authorised by the Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, and his cabinet. Charcoal produced the highest yield of any UK nuclear test at NTS up to that date. The design saved 166 kg of plutonium across the Polaris warhead stockpile, and reduced the cost of its production by £2.5 million. This was the last UK nuclear test for nine years; in 1965, Wilson suspended all nuclear testing on the grounds that it was unnecessary.[43][42]

In November 1972, the British government secured permission to conduct three more tests at the NTS as part of the Super Antelope, a component of the Chevaline programme, which aimed to harden the UK Polaris missiles against Soviet countermeasures. The first test was Arbor Fallon on 17 July 1974, which conducted in collaboration with LLNL, as it was the designer of the original Polaris warhead. It was Anvil Banon on 26 August 1976 and Cresset Fondutta 11 April 1978. These aimed to produced a lighter weight which would therefore have the same or greater range than the original ET.317, as shorter range drastically reduced the sea room in which the submarines could operate. A complication arose in 1976 in the form of the Threshold Test Ban Treaty, which limited tests to 150 kilotonnes of TNT (630 TJ). [44][45] Three more tests of Chevaline were subsequently added. Quicksilver Quargel on 20 November 1978 was a test of a warhead which could survive a high-speed re-entry. It worked as designed, producing a yield of 47 kilotonnes of TNT (200 TJ). Quicksilver Nessel on 29 August 1979 tested a new lightweight primary, which was of great interest to the Americans. Finally, there was Tinderbox Colwick on 26 April 1980.[44][46]

Starting with Guardian Dutchess on 24 October 1980, British tests were aimed at developing a warhead for a UK Trident missile system. The decision to acquire Trident meant that from 1978, British designers had access to American data on the effects of nuclear weapons on military systems, which had significant effect on designs. The shift to Trident meant that after six tests in collaboration with LLNL, the British testing now switched back to collaboration with LANL. Starting with Cresset Fondutta testing moved out to the Pahute Mesa, where tests could be conducted with less seismic impact on populated areas such as Las Vegas. Tests in Areas 19 and 20 involved travelling up to 60 miles (97 km) from the base camp in Mercury, Nevada. After the Praetorian Rousanne test with LANL on 12 November 1981, LLNL again became the American partner, starting with Praetorian Gibne on 12 April 1982. The final test at NTS was Julin Bristol on 26 November 1991.[47]

In all, 24 British nuclear tests were conducted at the NTS.[47]

Subcritical testing

Preparations were under way for another test in 1992 when President George H. W. Bush announced a moratorium on testing, much to the surprise of both American and British personnel at the NTS. This moratorium was extended by his successor, President Bill Clinton. In 1996, the United States signed the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), but the US Senate failed to ratify it in 1999.[48] The United Kingdom signed the CTBT in 1996, and ratified it in 1998 becoming, with France, the first two of the five declared nuclear-weapon states to ratify it.[49] This ratification confirmed the UK commitment towards ending nuclear test explosions in the world.

Subcritical British nuclear tests continued, notably Etna (Vito) on 14 February 2002 and Krakatau on 23 February 2006.[50][51][52] Subcritical tests are any type of tests involving nuclear materials and possibly chemical high explosives that purposely result in no yield. The name refers to the lack of creation of a critical mass of fissile material. They are the only type of tests allowed under the interpretation of the CTBT tacitly agreed to by the major atomic powers.[53][54]

Summary

| Name | Date time (UTC) | Local time zone | Location | Elevation + height | Delivery, Purpose | Device | Yield | Fallout | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nougat/Pampas | 1 March 1962 19:10:00.09 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U3al 37°02′28″N 116°01′46″W / 37.04118°N 116.02952°W | 1,196 m (3,924 ft) - 363.14 m (1,191.4 ft) | underground shaft | 9.5 kt | Venting detected off site, 2 kCi (74 TBq) | [55][56][57][58] | |

| Storax/Tendrac | 7 December 1962 19:00:00.1 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U3ba 37°03′06″N 116°01′48″W / 37.05174°N 116.03002°W | 1,202 m (3,944 ft) - 302.67 m (993.0 ft) | underground shaft | 10 kt | [56][57][58] | ||

| Whetstone/Cormorant | 17 July 1964 17:18:30.03 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U3df 37°01′03″N 116°01′46″W / 37.01761°N 116.02956°W | 1,184 m (3,885 ft) - 271.64 m (891.2 ft) | underground shaft | 2 kt | Venting detected on site, 11 Ci (410 GBq) | [55][56][57][58][59] | |

| Whetstone/Courser | 25 September 1964 17:02:00.03 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U3do 37°04′21″N 116°00′58″W / 37.07245°N 116.01614°W | 1,237 m (4,058 ft) - 358.99 m (1,177.8 ft) | underground shaft | no yield | [56][58] | ||

| Flintlock/Charcoal | 10 September 1965 17:12:00.03 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U7g 37°04′41″N 116°01′03″W / 37.07797°N 116.01745°W | 1,245 m (4,085 ft) - 455.44 m (1,494.2 ft) | underground shaft, weapons development |

Polaris warhead? | 29 kt | [56][57][58] | |

| Arbor/Fallon | 23 May 1974 13:38:30.164 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U2dv 37°07′28″N 116°04′47″W / 37.12455°N 116.07975°W | 1,276 m (4,186 ft) - 466.04 m (1,529.0 ft) | underground shaft, weapons development |

Chevaline warhead? | 20 kt | Venting detected, 72 Ci (2,700 GBq) | [55][56][57][58] |

| Anvil/Banon | 26 August 1976 14:30:00.168 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U2dz 37°07′31″N 116°04′59″W / 37.125199°N 116.083193°W | 1,275 m (4,183 ft) - 536.4 m (1,760 ft) | underground shaft, weapons development |

Chevaline warhead? | 51 kt | Venting detected, 6 Ci (220 GBq) | [55][56][57][58] |

| Cresset/Fondutta | 11 April 1978 15:30:00.161 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U19zs 37°17′59″N 116°19′36″W / 37.29963°N 116.3267°W | 2,072 m (6,798 ft) - 633.07 m (2,077.0 ft) | underground shaft, weapons development |

Chevaline warhead? | 67 kt | [56][57][58] | |

| Quicksilver/Quargel | 18 November 1978 19:00:00.166 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U2fb 37°07′36″N 116°05′05″W / 37.12675°N 116.08484°W | 1,275 m (4,183 ft) - 542 m (1,778 ft) | underground shaft | Chevaline warhead? | 38 kt | Venting detected, 7 Ci (260 GBq) | [55][56][57][58] |

| Quicksilver/Nessel | 29 August 1979 15:08:00.171 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U2ep 37°07′16″N 116°04′00″W / 37.12122°N 116.06659°W | 1,260 m (4,130 ft) - 464 m (1,522 ft) | underground shaft | Chevaline warhead? | 20 kt | Venting detected | [56][57][58] |

| Tinderbox/Colwick | 26 April 1980 17:00:00.083 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U20ac 37°14′54″N 116°25′23″W / 37.24838°N 116.42311°W | 1,946 m (6,385 ft) - 633 m (2,077 ft) | underground shaft | Chevaline warhead? | 140 kt | Venting detected | [56][57][58] |

| Guardian/Dutchess | 24 October 1980 19:15:00.116 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U7bm 37°04′28″N 116°00′00″W / 37.07456°N 116.00003°W | 1,265 m (4,150 ft) - 426.72 m (1,400.0 ft) | underground shaft | 10 kt | [56][57][58] | ||

| Guardian/Serpa | 17 December 1980 15:10:00.086 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U19ai 37°19′29″N 116°18′58″W / 37.32476°N 116.3160°W | 2,028 m (6,654 ft) - 572.7 m (1,879 ft) | underground shaft | Chevaline warhead? | 35 kt | [56][57][58] | |

| Praetorian/Rousanne | 12 November 1981 15:00:00.1 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U4p 37°06′29″N 116°03′00″W / 37.10805°N 116.04993°W | 1,243 m (4,078 ft) - 517.2 m (1,697 ft) | underground shaft | Chevaline warhead? | 77 kt | [56][57][58] | |

| Praetorian/Gibne | 25 April 1982 18:05:00.008 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U20ah 37°15′21″N 116°25′24″W / 37.2558°N 116.42327°W | 1,937 m (6,355 ft) - 570 m (1,870 ft) | underground shaft | Chevaline warhead? | 89 kt | Venting detected, 0.1 Ci (3.7 GBq) | [55][56][57][58] |

| Phalanx/Armada | 22 April 1983 13:53:00.085 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U9cs 37°06′41″N 116°01′23″W / 37.11144°N 116.02319°W | 1,296 m (4,252 ft) - 265 m (869 ft) | underground shaft | Trident warhead? | 1.5 kt | I-131 venting detected, 0 | [55][56][57][58][60] |

| Fusileer/Mundo | 1 May 1984 19:05:00.093 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U7bo 37°06′22″N 116°01′24″W / 37.10612°N 116.02322°W | 1,292 m (4,239 ft) - 566 m (1,857 ft) | underground shaft, weapons development |

Trident warhead? | 77 kt | [56][57][58] | |

| Grenadier/Egmont | 9 December 1984 19:40:00.089 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U20al 37°16′12″N 116°29′55″W / 37.27004°N 116.4985°W | 1,839 m (6,033 ft) - 546 m (1,791 ft) | underground shaft, weapons development |

Trident warhead? | 103 kt | [56][57][58] | |

| Charioteer/Kinibito | 5 December 1985 15:00:00.067 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U3me 37°03′11″N 116°02′47″W / 37.05313°N 116.04628°W | 1,208 m (3,963 ft) - 579.42 m (1,901.0 ft) | underground shaft, weapons development |

Trident warhead? | 110 kt | [56][57][58] | |

| Charioteer/Darwin | 25 June 1986 20:27:45.092 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U20aq 37°15′52″N 116°30′02″W / 37.26451°N 116.50045°W | 1,849 m (6,066 ft) - 548.95 m (1,801.0 ft) | underground shaft, weapons development |

Trident warhead? | 89 kt | [56][57][58] | |

| Musketeer/Midland | 16 July 1987 19:00:00.077 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U7by 37°06′13″N 116°01′27″W / 37.10361°N 116.02413°W | 1,284 m (4,213 ft) - 486.77 m (1,597.0 ft) | underground shaft | Trident warhead? | 20 kt | [56][57][58] | |

| Aqueduct/Barnwell | 8 December 1989 15:00:00.087 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U20az 37°13′52″N 116°24′37″W / 37.23115°N 116.41032°W | 2,031 m (6,663 ft) - 600.8 m (1,971 ft) | underground shaft, weapons development |

Trident warhead? | 120 kt | Venting detected, 0.1 Ci (3.7 GBq) | [55][56][57][58] |

| Sculpin/Houston | 14 November 1990 19:17:00.071 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U19az 37°13′38″N 116°22′20″W / 37.22735°N 116.37217°W | 2,031 m (6,663 ft) - 594.4 m (1,950 ft) | underground shaft, weapons development |

Trident warhead? | 103 kt | Venting detected | [56][57][58] |

| Julin/Bristol | 26 November 1991 18:35:00.073 | PST (-8 hrs) |

NTS Area U4av 37°05′47″N 116°04′14″W / 37.09644°N 116.07047°W | 1,246 m (4,088 ft) - 457 m (1,499 ft) | underground shaft, weapons development |

Trident Low Yield warhead? | 11 kt | [56][57][58] |

Notes

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 108–111.

- ^ Jones 2017, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Gowing & Arnold 1974a, pp. 181–184.

- ^ Cathcart 1995, pp. 23–24, 48, 57.

- ^ Gowing & Arnold 1974b, pp. 476–478.

- ^ Arnold & Smith 2006, p. 17.

- ^ Gowing & Arnold 1974a, pp. 307–308.

- ^ a b Gowing & Arnold 1974b, pp. 476–479.

- ^ Botti 1987, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Arnold & Smith 2006, p. 19.

- ^ Jones 2017, p. 25.

- ^ Arnold & Smith 2006, pp. 106–110.

- ^ Arnold & Smith 2006, p. 138.

- ^ Gowing & Arnold 1974b, pp. 498–502.

- ^ Arnold & Pyne 2001, pp. 16–20.

- ^ Arnold & Pyne 2001, p. 53.

- ^ Arnold & Pyne 2001, pp. 55–57.

- ^ "We Bar H-Bomb Test Here So Britain Seeks Ocean Site". The Argus (Melbourne). Victoria, Australia. 19 February 1955. p. 1. Retrieved 28 May 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Arnold & Pyne 2001, p. 104.

- ^ Botti 1987, pp. 159–160.

- ^ Arnold & Pyne 2001, p. 147.

- ^ Baylis 1994, pp. 166–170.

- ^ Arnold & Pyne 2001, pp. 160–162.

- ^ Arnold & Pyne 2001, pp. 189–191.

- ^ Botti 1987, pp. 199–201.

- ^ Arnold & Pyne 2001, p. 199.

- ^ "Foreign Relations of the United States, 1955–1957, Western Europe and Canada, Volume XXVII – Document 306". Office of the Historian, United States Department of State. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Botti 1987, pp. 232–233.

- ^ Botti 1987, pp. 234–236.

- ^ Agreement between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland for Cooperation on the uses of Atomic Energy for Mutual Defence Purposes (PDF) (Report). UK Parliament. 3 July 1958. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ Botti 1987, p. 238.

- ^ Macmillan 1971, p. 323.

- ^ Wade 2008, p. 200.

- ^ a b Moore 2010, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Wade 2008, p. 204.

- ^ a b c d Wade 2008, pp. 201–202.

- ^ a b Moore 2010, p. 203.

- ^ "Plutonium Dispersal Sites at the Nevada Test Site" (PDF). United States Department of Energy. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ Jones 2017, p. 444.

- ^ Jones 2017, pp. 413–415.

- ^ a b Stoddart 2012, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Wade 2008, p. 203.

- ^ a b Wade 2008, pp. 205–206.

- ^ Stoddart 2014a, pp. 156–162.

- ^ Stoddart 2014b, pp. 24–26.

- ^ a b Wade 2008, pp. 206–210.

- ^ "Senate Rejects Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty; Clinton Vows to Continue Moratorium". Arms Control Association. 1 September 1999. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ "Country Profiles – United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland: CTBTO Preparatory Commission". Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ Sample, Ian (25 February 2006). "Is Britain conducting nuclear tests?". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ "U.S., Britain conduct nuclear experiment at Nevada Test Site". Las Vegas Sun. 23 February 2006. Archived from the original on 5 May 2006. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 5 March 2006 suggested (help) - ^ NNSA (26 February 2006). "Krakatau Subcritical Experiment Scheduled" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2010. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ Medalia, Jonathan (12 March 2008). "Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty: Issues and Arguments" (PDF). CRS Report for Congress. Congressional Research Service: 20–22. RL34394. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ Medalia, Jonathan (11 March 2005). "Nuclear Weapons: Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty" (PDF). CRS Issue Brief for Congress. Congressional Record Service. IB92099. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Estimated exposures and thyroid doses received by the American people from Iodine-131 in fallout following Nevada atmospheric nuclear bomb tests, Chapter 2" (PDF). National Cancer Institute. 1997. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Official list of underground nuclear explosions (Technical report). Sandia National Laboratories. 1 July 1994. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Norris, Burrows & Fieldhouse 1994, pp. 402–404.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x United States Nuclear Tests: July 1945 through September 1992 (PDF) (DOE/NV-209 REV15). Las Vegas, NV: Department of Energy, Nevada Operations Office. 1 December 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2010. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

{{cite tech report}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Nuclear explosion database". SMDC. 2004. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Radiological Effluents Released from U.S. Continental Tests 1961 Through 1992 (DOE/NV-317 Rev. 1) (PDF) (Technical report). DOE Nevada Operations Office. August 1996. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

{{cite tech report}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

References

- Arnold, Lorna; Pyne, Katherine (2001). Britain and the H-bomb. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York: Palgrave. ISBN 978-0-230-59977-2. OCLC 753874620.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Arnold, Lorna; Smith, Mark (2006). Britain, Australia and the Bomb: The Nuclear Tests and Their Aftermath. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-2102-4. OCLC 70673342.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Baylis, John (Summer 1994). "The Development of Britain's Thermonuclear Capability 1954–61: Myth or Reality?". Contemporary Record. 8 (1): 159–164. ISSN 1361-9462.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Botti, Timothy J. (1987). The Long Wait: The Forging of the Anglo-American Nuclear Alliance, 1945–58. Contributions in Military Studies. New York: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-25902-9. OCLC 464084495.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cathcart, Brian (1995). Test of Greatness: Britain's Struggle for the Atom Bomb. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5225-0. OCLC 31241690.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gowing, Margaret (1964). Britain and Atomic Energy 1939–1945. London: Macmillan. OCLC 3195209.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gowing, Margaret; Arnold, Lorna (1974a). Independence and Deterrence: Britain and Atomic Energy, 1945–1952, Volume 1, Policy Making. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-15781-7. OCLC 611555258.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gowing, Margaret; Arnold, Lorna (1974b). Independence and Deterrence: Britain and Atomic Energy, 1945–1952, Volume 2, Policy and Execution. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-16695-6. OCLC 946341039.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jones, Jeffrey (2017). Volume I: From the V-Bomber Era to the Arrival of Polaris, 1945–1964. The Official History of the UK Strategic Nuclear Deterrent. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-67493-6. OCLC 1005663721.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Macmillan, Harold (1971). Riding the Storm: 1956–1959. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-10310-4. OCLC 198741.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Moore, Richard (2010). Nuclear Illusion, Nuclear Reality: Britain, the United States, and Nuclear Weapons, 1958–64. Nuclear Weapons and International Security since 1945. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-21775-1. OCLC 705646392.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Norris, Robert S.; Burrows, Andrew S.; Fieldhouse, Richard W. (1994). Nuclear Weapons Databook, Volume 5: British, French, and Chinese Nuclear Weapons. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-1611-6. OCLC 311858583.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stoddart, Kristan (2012). Losing an Empire and Finding a Role: Britain, the USA, NATO and Nuclear Weapons, 1964–70. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-349-33656-2. OCLC 951512907.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stoddart, Kristan (2014a). The Sword and the Shield: Britain, America, NATO and Nuclear Weapons, 1970–1976. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-30093-4. OCLC 870285634.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stoddart, Kristan (2014b). Facing Down the Soviet Union: Britain, the USA, NATO and Nuclear Weapons, 1976–83. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-44031-0. OCLC 900698250.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wade, Troy E. II (2008). "Nuclear Testing: A US Perspective". In Mackby, Jenifer; Cornish, Paul (eds.). US-UK Nuclear Cooperation After 50 Years. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies Press. pp. 200–211. ISBN 978-0-89206-530-1. OCLC 845346116.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)