Gliese 581 planetary system: Difference between revisions

→Planets: fix overview table |

m →Planets: Properly fixing it. |

||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center; margin-left:auto; margin-right:auto;" |

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center; margin-left:auto; margin-right:auto;" |

||

|+ The |

|+ The Gliese 581 planetary system <ref name="SCI-20140703">{{cite journal |last=Robertson |first=Paul |last2=Mahadevan |first2=Suvrath |last3=Endl |first3=Michael |last4=Roy |first4=Arpita |title=Stellar activity masquerading as planets in the habitable zone of the M dwarf Gliese 581 |url=http://www.sciencemag.org/content/early/2014/07/02/science.1253253.abstract |journal=[[Science (journal)|Science]] |date=3 July 2014 |doi=10.1126/science.1253253 |accessdate=8 July 2014 |arxiv=1407.1049 |bibcode=2014Sci...345..440R |volume=345 |pages=440–444 }}</ref> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

! align=center style="background:#a0b0ff;"| Companion<br /><small>(in order from star)</small> |

! align=center style="background:#a0b0ff;"| Companion<br /><small>(in order from star)</small> |

||

Revision as of 15:33, 29 September 2017

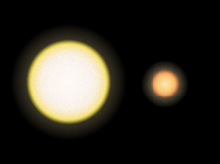

The orbits of planets in the Gliese 581 planetary system compared to those of the Solar System | |

| Age | 7–11 billion years |

|---|---|

| Location | Libra constellation |

| Right ascension | 15h 19m 26.8250s |

| Declination | −07° 43′ 20.209″ |

| Population | |

| Known stars | 1 |

| Known planets | 3–5 |

| Planetary system | |

The Gliese 581 planetary system is the gravitationally bound system comprising Gliese 581 and the objects that orbit it. The system is known to consist of at least three planets (possibly up to five) along with a debris disc discovered using the radial velocity method. The system's notability is due primarily to early exoplanetology discoveries, between 2008 and 2010, of possible terrestrial planets orbiting within its habitable zone and the system's relatively close proximity to the Solar System at 20 light years away. Though its observation history is controversial due to false detections and conjecture, and with the radial velocity method yielding little information about the planets themselves beyond their mass.

The confirmed planets are believed to be located close to the star with near-circular orbits. In order of distance from the star, these are Gliese 581e, Gliese 581b, and Gliese 581c. The letters represent the discovery order, with b being the first planet to be discovered around the star.

Observation history

The first announcement of a planet around the star was Gliese 581b discovered by astronomers at the Observatory of Geneva in Switzerland and Grenoble University in France. Detected in August 2005 and using extensive data from the ESO/HARPS spectrometer it was the fifth planet to be discovered around a red dwarf.[1] Further observations by the same group resulted in the detection of two more planets, Gliese 581c and Gliese 581d.[2][3][4] The orbital period of Gliese 581d was originally thought to be 83 days but was later revised to a lower value of 67 days.[5] The revised orbital distance would place it at the outer limits of the habitable zone, the distance at which it is believed possible for liquid water to exist on the surface of a planetary body, given favourable atmospheric conditions. Gliese 581d was estimated to receive about 30% of the intensity of light the Earth receives from the Sun. By comparison, sunlight on Mars has about 40% of the intensity of that on Earth, though if high levels of carbon dioxide are present in the planetary atmosphere, the greenhouse effect could keep temperatures above freezing.[6]

The next discovery was the inner planet Gliese 581e, also by the Observatory of Geneva and using data from the HARPS instrument, was announced on 21 April 2009.[5] This planet, at a minimum mass of 1.9 Earths, was at the time the least massive confirmed exoplanet identified around a main-sequence star.[4]

On September 29, 2010, astronomers using the Keck Observatory proposed two additional planets, Gliese 581f and Gliese 581g, both in nearly circular orbits based on analysis of a combination of data sets from the HARPS and HIRES instruments. The proposed planet Gliese 581f was thought to be a 7 Earth-mass planet in a 433-day orbit and too cold to support liquid water. The candidate planet Gliese 581 g attracted more attention: nicknamed Zarmina by one of its discoverers,[7] the predicted mass of Gliese 581 g was between 3 and 4 Earth-masses, with an orbital period of 37 days. The orbital distance was calculated to be well within the star's habitable zone, though the planet was expected to be tidally locked with one side of the planet always facing the star.[8][9] In an interview with Lisa-Joy Zgorski of the National Science Foundation, Steven Vogt was asked what he thought about the chances of life existing on Gliese 581 g. Vogt was optimistic: "I'm not a biologist, nor do I want to play one on TV. Personally, given the ubiquity and propensity of life to flourish wherever it can, I would say that ... the chances of life on this planet are 100%. I have almost no doubt about it."[10]

Two weeks after the announcement of the discovery of Gliese 581f and Gliese 581g, astronomer Francesco Pepe of the Geneva Observatory reported that in a new analysis of 179 measurements taken by the HARPS spectrograph over 6.5 years, neither planet g nor planet f was detectable,[11][12] and the relevant measurements were included in a paper uploaded to the arXiv preprint server, though still unpublished in a refereed journal.[13] The non-existence of Gliese 581f was accepted relatively quickly: it was shown that the radial velocity variations that led to the claimed discovery of Gliese 581f were instead associated with the stellar activity cycle rather than an orbiting planet.[14] Nevertheless, the existence of planet g remained controversial: Vogt responded in the media that he stood by the discovery[15][16] and questions arose as to whether the effect was due to the assumption of circular rather than eccentric orbits[17] or the statistical methods used.[18]

Bayesian analysis found no clear evidence for a fifth planetary signal in the combined HIRES/HARPS data set,[19][20] though other studies led to the conclusion that the data did support the existence of planet g, albeit with strong degeneracies in the parameters as a result of the first eccentric harmonic with the outer planet Gliese 581d.[21]

Using the assumption that the noise present in the data was correlated (red noise rather than white noise), Roman Baluev called into question not only the existence of planet g, but Gliese 581d as well, suggesting there were only three planets (Gliese 581b, c, and e) present.[22][23]

On 27 November 2012, the European Space Agency announced that the Herschel space observatory had discovered a comet belt "at 25 ± 12 AU to more than 60 AU".[24] It must have "at least 10 times" as many comets as does the Solar system. This likely rules out Saturn-mass planets beyond 0.75 AU.[25] However another (undiscovered) planet further out, say a Neptune-mass planet at 5 AU, might be required to keep the comet belt replenished.[24]

A different objection against the existence of Gliese 581d was offered in a 2014 study whose authors argued that Gliese 581d is "an artifact of stellar activity which, when incompletely corrected, causes the false detection of the planet g."[26][27] This remains controversial.[28]

Gliese 581

Gliese 581 is a star of spectral type M3V (a red dwarf) about twenty light years away from Earth in the Libra constellation. Its estimated mass is about a third of that of the Sun, and it is the 89th closest known star to the Sun.

Gliese 581 is one of the oldest, least active M dwarfs, its low stellar activity bodes better than most for its planets retaining significant atmospheres and from the sterilising impact stellar flares.[29]

Planets

Ongoing analysis of the system has produced several models for the orbitral arrangement of the system. There is no current consensus and 3-planet, 4-planet, 5-planet and 6-planet models have been proposed to address the available radial velocity data. Most of these models predict, however, that the inner planets are close in with circular orbits, while outer planets, particularly Gliese 581d, should it exist, are on more elliptical orbits.

Models of the habitable zone of Gliese 581 show that it extends from about 0.1 to 0.5 AU taking in part of the orbit of Gliese 581d. The first three planets orbit closer to the star than the inner edge of the habitable zone, with planets d and (g) orbiting within it.[26]

| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (days) |

Eccentricity | Inclination | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| e | ≥1.7 ± 0.2 M🜨 | 0.02815 ± 0.00006 | 3.1490 ± 0.0002 | 0.00-0.06 | — | — |

| b | ≥15.8 ± 0.3 M🜨 | 0.04061 ± 0.00003 | 5.3686 ± 0.0001 | 0.00-0.03 | — | — |

| c | ≥5.5 ± 0.3 M🜨 | 0.0721 ± 0.0003 | 12.914 ± 0.002 | 0.00-0.06 | — | — |

| g (unconfirmed) | ≥2.2 M🜨 | 0.13 | 32 | 0.00 | — | — |

| d[30] (unconfirmed) | 6.98 ± 0.3 M🜨 | 0.21847 ± 0.00028 | 66.87 ± 0.13 | 0.00-0.25 | — | — |

| Debris disk[24] | 25 ± 12 AU–>60 AU | 30° – 70° | — | |||

Confirmed planets

Gliese 581e

Gliese 581e is the innermost planet and, with a minimum mass of 1.7 Earth masses, is the least massive of the three. Discovered in 2009, it is also the most recent confirmed planet to have been discovered in this system.[5] It takes 3.15 days to complete an orbit. Initial analyses suggested that the planet's orbit is quite elliptical but after correcting the radial velocity measurements for stellar activity, the data now indicate a circular orbit.[26]

Gliese 581b

Gliese 581b is the most massive planet known to be orbiting Gliese 581 and was the first to be discovered.[1]

Gliese 581c

Gliese 581c is the third planet orbiting Gliese 581. It was discovered in April 2007.[2] In their 2007 paper, Udry et al. asserted that if Gliese 581c has an Earth-type composition, it would have a radius of 1.5R⊕, which would have made it at the time "the most Earth-like of all known exoplanets".[2] A direct measurement of the radius cannot be taken because, viewed from Earth, the planet does not transit its star. The minimum mass of the planet is 5.5 times that of Earth. The planet initially attracted attention as being potentially habitable, though this has since been discounted.[31] The mean blackbody surface temperature has been estimated to lie between −3 °C (for a Venus-like albedo) and 40 °C (for an Earth-like albedo),[2] however, the temperatures could be much higher (about 500 degrees Celsius) due to a runaway greenhouse effect akin to that of Venus.[31][32] Some astronomers believe the system may have undergone planetary migration and Gliese 581c may have formed beyond the frost line, with a composition similar to icy bodies like Ganymede. Gliese 581c completes a full orbit in just under 13 days.[2]

Unconfirmed planets

Gliese 581g

Gliese 581g, unofficially known as Zarmina (or Zarmina's World), is an unconfirmed (and disputed)[33] exoplanet claimed to orbit within the Gliese 581 planetary system, twenty light-years from Earth. It was discovered by the Lick–Carnegie Exoplanet Survey, and is the sixth planet orbiting the star;[34] however, its existence could not be confirmed by the European Southern Observatory (ESO) / High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS) survey team, and its existence remains controversial. It is thought to be near the middle of the habitable zone of its star.[35] That means it could sustain liquid water—a necessity for all known life—on its surface, if there are favorable atmospheric conditions on the planet.

Gliese 581g was claimed to be detected by astronomers of the Lick–Carnegie Exoplanet Survey. The authors stated that data sets from both High Resolution Echelle Spectrometer (HIRES) and HARPS were needed to sense the planet; however, the ESO/HARPS survey team could not confirm its existence. The planet remained unconfirmed as consensus for its existence could not be reached. Additional reanalysis only found evidence for four planets, but the discoverer, Steven S. Vogt, did not agree with those conclusions; another study by Guillem Anglada-Escudé later supported the planet's existence. In 2012, a reanalysis by Vogt supported its existence.[36] A new study in 2014 concluded that it was a false positive;[37] however, in 2015, a reanalysis of the data suggested that it could still exist. The planet is thought to be tidally locked to its star. If the planet has a dense atmosphere, it may be able to circulate heat. The actual habitability of the planet depends on the composition of its surface and the atmosphere. It is thought to have temperatures around −37 to −11 °C (−35 to 10 °F). By comparison, Earth has an average surface temperature of 15 °C (59 °F)—while Mars has an average surface temperatures of about −63 °C (−81 °F). The planet has, according to Vogt, a "100%"[38] chance of supporting life, but this is disputed. The supposed detection of Gliese 581g foreshadows what Vogt calls "a second Age of Discovery".[8]

Gliese 581d

Gliese 581d is an exoplanet that was once considered disputed due to inaccurate analysis caused by noise and stellar activity,[26][27] but reanalysis suggests that it does in fact exist, despite stellar variability.[30] Its mass is thought to be 6.98 Earths and its radius is thought to be 2.2R⊕. It is considered to be a super-Earth, but remarkable in that its orbit is inside the habitable zone and has a solid surface allowing for any water present on its surface to form liquid oceans and even landmasses characteristic of Earth’s surface, although with a much higher surface gravity. Its orbital period is thought to be 66.87 days long, with a semi-major axis of 0.21847, with an unconfirmed eccentricity. Analysis suggests that it orbits within the star's habitable zone, where the temperatures are just right to support life.[39][31][32]

SETI

The Gliese 581 system has been the target of both SETI and Active SETI searches for extraterrestrial life. A Message from Earth (AMFE) is a high-powered digital radio signal that was sent on October 9, 2008, toward Gliese 581c. The signal is a digital time capsule containing 501 messages that were selected through a competition on the social networking site Bebo. The message was sent using the Yevpatoria RT-70 radio telescope radar telescope of the National Space Agency of Ukraine. The signal will reach Gliese 581 in early 2029.[citation needed]

Using optical SETI, Ragbir Bhathal claimed to have detected an unexplained pulse of light from the direction of the Gliese 581 system in 2008.[40]

In 2012, the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research at Curtin University in Perth, Gliese 581 was precisely targeted by Australian Long Baseline Array using three radio telescope facilities across Australia and the Very Long Baseline Interferometry technique, however no candidate signals were found.[41]

Debris disk

At the outer edge of the system is a massive debris disk containing more comets than the Solar System. The debris disc has an inclination between 30° and 70°.[24] If the planetary orbits lie in the same plane, their masses would be between 1.1 and 2 times the minimum mass values.[note 1]

Notes

- ^ The radial velocity method allows the determination of the minimum mass which is the product of the true mass with the sine of the orbital inclination, denoted m sin i. In general the inclination is unknown. For a given inclination, the true mass is therefore the minimum mass multiplied by 1/sin i.

References

- ^ a b Bonfils, X.; et al. (2005). "The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets VI: A Neptune-mass planet around the nearby M dwarf Gl 581". Astronomy and Astrophysics Letters. 443 (3): L15–L18. arXiv:astro-ph/0509211. Bibcode:2005A&A...443L..15B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200500193.

- ^ a b c d e Udry, S; et al. (2007). "The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets XI: Super-Earths (5 and 8 M⊕) in a 3-planet system" (PDF). Astronomy and Astrophysics Letters. 469 (3): L43–L47. arXiv:0704.3841. Bibcode:2007A&A...469L..43U. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20077612.

- ^ "New 'super-Earth' found in space". BBC News. 25 April 2007. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- ^ a b Rincon, P.; Amos, J. (21 April 2009). "Lightest exoplanet is discovered". BBC News. Retrieved 2009-04-21.

- ^ a b c Mayor, M.; et al. (2009). "The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets XVIII: An Earth-mass planet in the GJ 581 planetary system" (PDF). Astronomy and Astrophysics. 507: 487–494. arXiv:0906.2780. Bibcode:2009A&A...507..487M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200912172. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-05-21.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ von Bloh, W.; et al. (2008). "Habitability of Super-Earths: Gliese 581c and 581d". Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. 3. arXiv:0712.3219. doi:10.1017/S1743921308017031.

- ^ "The astrophysicist who discovered Zarmina describes life on "second Earth"". 1 October 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-01.

- ^ a b Vogt, S. S.; et al. (2010). "The Lick-Carnegie Exoplanet Survey: A 3.1 M_Earth Planet in the Habitable Zone of the Nearby M3V Star Gliese 581". The Astrophysical Journal. 723: 954–965. arXiv:1009.5733. Bibcode:2010ApJ...723..954V. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/723/1/954.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|class=ignored (help) - ^ "Keck Observatory discovers the first Goldilocks exoplanet" (Press release). Keck Observatory. 29 September 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

- ^ NSF. Press Release 10-172 – Video. Event occurs at 41:25–42:31. See Overbye, Dennis (2010-09-29). "New Planet May Be Able to Nurture Organisms". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-09-30.

- ^ Kerr, Richard A. (2010-10-12). "Recently Discovered Habitable World May Not Exist". Science Now. AAAS. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

- ^ Mullen, Leslie (2010-10-12). "Doubt Cast on Existence of Habitable Alien World". Astrobiology. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

- ^ T. Forveille, X. Bonfils, X.Delfosse, R. Alonso, S. Udry, F. Bouchy, M. Gillon, C. Lovis, V. Neves, M. Mayor, F. Pepe, D. Queloz, N.C. Santos, D. Segransan, J.M. Almenara, H. Deeg, M. Rabus (2011-09-12). "The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets XXXII. Only 4 planets in the Gl 581 system". arXiv:1109.2505 [astro-ph.EP].

{{cite arXiv}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Robertson, Paul; Endl, Michael; Cochran, William D.; Dodson-Robinson, Sarah E. (2013). "Hα Activity of Old M Dwarfs: Stellar Cycles and Mean Activity Levels for 93 Low-mass Stars in the Solar Neighborhood". The Astrophysical Journal. 764 (1): article id. 3. arXiv:1211.6091. Bibcode:2013ApJ...764....3R. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/764/1/3.

- ^ Grossman, Lisa (2010-10-12). "Exoplanet Wars: "First Habitable World" May Not Exist". Wired. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

- ^ Wall, Mike (2010-10-13). "Astronomer Stands By Discovery of Alien Planet Gliese 581 g Amid Doubts". Space.com. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ Cowen, Ron (2010-10-13). "Swiss team fails to confirm recent discovery of an extrasolar planet that might have right conditions for life". Science News. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ Rene Andrae; Tim Schulze-Hartung; Peter Melchior (2010). "Dos and don'ts of reduced chi-squared". arXiv:1012.3754 [astro-ph.IM].

- ^ Gregory (2011). "Bayesian Re-analysis of the Gliese 581 Exoplanet System". arXiv:1101.0800 [astro-ph.SR].

- ^ Mikko Tuomi (2011). "Bayesian re-analysis of the radial velocities of Gliese 581. Evidence in favour of only four planetary companions". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 528: L5. arXiv:1102.3314. Bibcode:2011A&A...528L...5T. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201015995.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|class=ignored (help) - ^ Guillem Anglada-Escudé (2010). "Aliases of the first eccentric harmonic : Is GJ 581 g a genuine planet candidate?". arXiv:1011.0186 [astro-ph.EP].

- ^ Roman Baluev (2013). "The impact of red noise in radial velocity planet searches: Only three planets orbiting GJ581?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 429 (3): 2052–2068. arXiv:1209.3154. Bibcode:2013MNRAS.429.2052B. doi:10.1093/mnras/sts476.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Carlisle, Camille (3 July 2014). "The Planet That is No More". Sky & Telescope.com. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d J.-F. Lestrade; et al. (2012). "A DEBRIS Disk Around The Planet Hosting M-star GJ581 Spatially Resolved with Herschel". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 548: A86. arXiv:1211.4898. Bibcode:2012A&A...548A..86L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201220325.

- ^ ESA Herschel (27 November 2012). "Do missing Jupiters mean massive comet belts?".

- ^ a b c d e Robertson, Paul; Mahadevan, Suvrath; Endl, Michael; Roy, Arpita (3 July 2014). "Stellar activity masquerading as planets in the habitable zone of the M dwarf Gliese 581". Science. 345: 440–444. arXiv:1407.1049. Bibcode:2014Sci...345..440R. doi:10.1126/science.1253253. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ^ a b Quenqua, Douglas (7 July 2014). "Earthlike Planets May Be Merely an Illusion". New York Times. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ^ 'Habitable' planet GJ 581d previously dismissed as noise probably does exist

- ^ http://hpf.psu.edu/2014/07/03/gliese-581/

- ^ a b "Reanalysis of data suggests 'habitable' planet GJ 581d really could exist". Astronomy Now. 9 March 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ^ a b c von Bloh, W.; et al. (2007). "The Habitability of Super-Earths in Gliese 581". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 476 (3). Astronomy & Astrophysics: 1365–71. arXiv:0705.3758. Bibcode:2007A&A...476.1365V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20077939.

- ^ a b von Bloh, W.; et al. (2008). "Habitability of Super-Earths: Gliese 581c & 581d". Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. 3 (S249). International Astronomical Union: 503–506. arXiv:0712.3219. doi:10.1017/S1743921308017031.

- ^ Wall, Mike. "Gliese 581g Tops List of 5 Potentially Habitable Alien Planets". Space.com. Purch Group. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- ^ Hsu, Jeremy. "A Million Questions About Habitable Planet Gliese 581g (Okay, 12)". Space.com. Purch Group. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- ^ Howell, Elizabeth (May 4, 2016). "Gliese 581g: Potentially Habitable Planet — If It Exists". Space.com. Purch Group. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- ^ Wall, Mike. "Is Planet Gliese 581g Really the 'First Potentially Habitable' Alien World?". Space.com. Purch Group. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- ^ Grant, Andrew. "Habitable planets' reality questioned: star's magnetic activity could have led to false detections". Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ^ NSF. Press Release 10-172 – Video. Event occurs at 41:25–42:31. See Overbye, Dennis (September 29, 2010). "New Planet May Be Able to Nurture Organisms". The New York Times'. Retrieved September 30, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "First Habitable Exoplanet? Climate Simulation Reveals New Candidate That Could Support Earth-Like Life". ScienceDaily. 16 May 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- ^ http://www.space.com/9303-claim-alien-signal-planet-gliese-581g-called-very-suspicious.html

- ^ https://www.universetoday.com/95598/first-seti-search-of-gliese-581-finds-no-signs-of-et/