Transmission line: Difference between revisions

math format nudges (spacing) |

inserted alpha and beta as real & imag parts of gamma |

||

| Line 161: | Line 161: | ||

The solutions for <math>V(x)</math> and <math>I(x)</math> are: |

The solutions for <math>V(x)</math> and <math>I(x)</math> are: |

||

:<math>V(x) = V_{( |

:<math>V(x) = V_{(+)} e^{+\gamma\,x} + V_{(-)} e^{-\gamma\,x} \,</math> |

||

:<math>I(x) = \frac{1}{Z_0}\,\left( V_{( |

:<math>I(x) = \frac{1}{Z_0}\,\left( V_{(+)} e^{+\gamma\,x} - V_{(-)} e^{-\gamma\,x} \right) ~\,. </math> |

||

The constants <math>V_{(\pm)}</math> must be determined from boundary conditions. For a voltage pulse <math>V_{\mathrm{in}}(t) \,</math>, starting at <math>x = 0</math> and moving in the positive <math>x</math> direction, then the transmitted pulse <math>V_{\mathrm{out}}(x,t) \,</math> at position <math>x</math> can be obtained by computing the Fourier Transform, <math>\tilde{V}(\omega)</math>, of <math>V_{\mathrm{in}}(t) \,</math>, attenuating each frequency component by <math>e^{-\operatorname{Re}(\gamma)\,x} \,</math>, advancing its phase by <math>-\operatorname{Im}(\gamma)\,x\,</math>, and taking the [[Fourier inversion theorem|inverse Fourier Transform]]. The real and imaginary parts of <math>\gamma</math> can be computed as |

The constants <math>V_{(\pm)}</math> must be determined from boundary conditions. For a voltage pulse <math>V_{\mathrm{in}}(t) \,</math>, starting at <math>x = 0</math> and moving in the positive <math>x</math> direction, then the transmitted pulse <math>V_{\mathrm{out}}(x,t) \,</math> at position <math>x</math> can be obtained by computing the Fourier Transform, <math>\tilde{V}(\omega)</math>, of <math>V_{\mathrm{in}}(t) \,</math>, attenuating each frequency component by <math>e^{-\operatorname{Re}(\gamma)\,x} \,</math>, advancing its phase by <math>-\operatorname{Im}(\gamma)\,x\,</math>, and taking the [[Fourier inversion theorem|inverse Fourier Transform]]. The real and imaginary parts of <math>\gamma</math> can be computed as |

||

:<math>\operatorname{Re}(\gamma) = (a^2 + b^2)^{1/4} \cos(\mathrm{atan2}(b,a)/2) \,</math> |

:<math>\operatorname{Re}(\gamma) = \alpha = (a^2 + b^2)^{1/4} \cos(\mathrm{atan2}(b,a)/2) \,</math> |

||

:<math>\operatorname{Im}(\gamma) = (a^2 + b^2)^{1/4} \sin(\mathrm{atan2}(b,a)/2) \,</math> |

:<math>\operatorname{Im}(\gamma) = \beta = (a^2 + b^2)^{1/4} \sin(\mathrm{atan2}(b,a)/2) \,</math> |

||

where [[atan2]] is the two-parameter arctangent, and |

where [[atan2]] is the two-parameter arctangent, and |

||

| Line 179: | Line 179: | ||

For small losses and high frequencies, to first order in <math>\tfrac{R}{\omega\,L}</math> and <math>\tfrac{G}{\omega\,C}</math> one obtains |

For small losses and high frequencies, to first order in <math>\tfrac{R}{\omega\,L}</math> and <math>\tfrac{G}{\omega\,C}</math> one obtains |

||

:<math>\operatorname{Re}(\gamma) \approx \tfrac{1}{2}\sqrt{L\,C\,}\,\left( \frac{R}{L} + \frac{G}{C} \right) \,</math> |

:<math>\operatorname{Re}(\gamma) = \alpha \approx \tfrac{1}{2}\sqrt{L\,C\,}\,\left( \frac{R}{L} + \frac{G}{C} \right) \,</math> |

||

:<math>\operatorname{Im}(\gamma) \approx \omega\,\sqrt{L\,C\,} ~.\,</math> |

:<math>\operatorname{Im}(\gamma) = \beta \approx \omega\,\sqrt{L\,C\,} ~.\,</math> |

||

Noting that an advance in phase by <math>- \omega\,\delta</math> is equivalent to a time delay by <math>\delta</math>, <math>V_{out}(t)</math> can be simply computed as |

Noting that an advance in phase by <math>- \omega\,\delta</math> is equivalent to a time delay by <math>\delta</math>, <math>V_{out}(t)</math> can be simply computed as |

||

Revision as of 18:18, 19 September 2017

In communications and electronic engineering, a transmission line is a specialized cable or other structure designed to conduct alternating current of radio frequency, that is, currents with a frequency high enough that their wave nature must be taken into account. Transmission lines are used for purposes such as connecting radio transmitters and receivers with their antennas, distributing cable television signals, trunklines routing calls between telephone switching centres, computer network connections and high speed computer data buses.

This article covers two-conductor transmission line such as parallel line (ladder line), coaxial cable, stripline, and microstrip. Some sources also refer to waveguide, dielectric waveguide, and even optical fibre as transmission line, however these lines require different analytical techniques and so are not covered by this article; see Waveguide (electromagnetism).

Overview

Ordinary electrical cables suffice to carry low frequency alternating current (AC), such as mains power, which reverses direction 100 to 120 times per second, and audio signals. However, they cannot be used to carry currents in the radio frequency range,[1] above about 30 kHz, because the energy tends to radiate off the cable as radio waves, causing power losses. Radio frequency currents also tend to reflect from discontinuities in the cable such as connectors and joints, and travel back down the cable toward the source.[1][2] These reflections act as bottlenecks, preventing the signal power from reaching the destination. Transmission lines use specialized construction, and impedance matching, to carry electromagnetic signals with minimal reflections and power losses. The distinguishing feature of most transmission lines is that they have uniform cross sectional dimensions along their length, giving them a uniform impedance, called the characteristic impedance,[2][3][4] to prevent reflections. Types of transmission line include parallel line (ladder line, twisted pair), coaxial cable, and planar transmission lines such as stripline and microstrip.[5][6] The higher the frequency of electromagnetic waves moving through a given cable or medium, the shorter the wavelength of the waves. Transmission lines become necessary when the length of the cable is longer than a significant fraction of the transmitted frequency's wavelength.

At microwave frequencies and above, power losses in transmission lines become excessive, and waveguides are used instead,[1] which function as "pipes" to confine and guide the electromagnetic waves.[6] Some sources define waveguides as a type of transmission line;[6] however, this article will not include them. At even higher frequencies, in the terahertz, infrared and visible ranges, waveguides in turn become lossy, and optical methods, (such as lenses and mirrors), are used to guide electromagnetic waves.[6]

The theory of sound wave propagation is very similar mathematically to that of electromagnetic waves, so techniques from transmission line theory are also used to build structures to conduct acoustic waves; and these are called acoustic transmission lines.

History

Mathematical analysis of the behaviour of electrical transmission lines grew out of the work of James Clerk Maxwell, Lord Kelvin and Oliver Heaviside. In 1855 Lord Kelvin formulated a diffusion model of the current in a submarine cable. The model correctly predicted the poor performance of the 1858 trans-Atlantic submarine telegraph cable. In 1885 Heaviside published the first papers that described his analysis of propagation in cables and the modern form of the telegrapher's equations.[7]

Applicability

In many electric circuits, the length of the wires connecting the components can for the most part be ignored. That is, the voltage on the wire at a given time can be assumed to be the same at all points. However, when the voltage changes in a time interval comparable to the time it takes for the signal to travel down the wire, the length becomes important and the wire must be treated as a transmission line. Stated another way, the length of the wire is important when the signal includes frequency components with corresponding wavelengths comparable to or less than the length of the wire.

A common rule of thumb is that the cable or wire should be treated as a transmission line if the length is greater than 1/10 of the wavelength. At this length the phase delay and the interference of any reflections on the line become important and can lead to unpredictable behaviour in systems which have not been carefully designed using transmission line theory.

The four terminal model

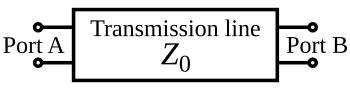

For the purposes of analysis, an electrical transmission line can be modelled as a two-port network (also called a quadripole), as follows:

In the simplest case, the network is assumed to be linear (i.e. the complex voltage across either port is proportional to the complex current flowing into it when there are no reflections), and the two ports are assumed to be interchangeable. If the transmission line is uniform along its length, then its behaviour is largely described by a single parameter called the characteristic impedance, symbol Z0. This is the ratio of the complex voltage of a given wave to the complex current of the same wave at any point on the line. Typical values of Z0 are 50 or 75 ohms for a coaxial cable, about 100 ohms for a twisted pair of wires, and about 300 ohms for a common type of untwisted pair used in radio transmission.

When sending power down a transmission line, it is usually desirable that as much power as possible will be absorbed by the load and as little as possible will be reflected back to the source. This can be ensured by making the load impedance equal to Z0, in which case the transmission line is said to be matched.

Some of the power that is fed into a transmission line is lost because of its resistance. This effect is called ohmic or resistive loss (see ohmic heating). At high frequencies, another effect called dielectric loss becomes significant, adding to the losses caused by resistance. Dielectric loss is caused when the insulating material inside the transmission line absorbs energy from the alternating electric field and converts it to heat (see dielectric heating). The transmission line is modelled with a resistance (R) and inductance (L) in series with a capacitance (C) and conductance (G) in parallel. The resistance and conductance contribute to the loss in a transmission line.

The total loss of power in a transmission line is often specified in decibels per metre (dB/m), and usually depends on the frequency of the signal. The manufacturer often supplies a chart showing the loss in dB/m at a range of frequencies. A loss of 3 dB corresponds approximately to a halving of the power.

High-frequency transmission lines can be defined as those designed to carry electromagnetic waves whose wavelengths are shorter than or comparable to the length of the line. Under these conditions, the approximations useful for calculations at lower frequencies are no longer accurate. This often occurs with radio, microwave and optical signals, metal mesh optical filters, and with the signals found in high-speed digital circuits.

Telegrapher's equations

The telegrapher's equations (or just telegraph equations) are a pair of linear differential equations which describe the voltage () and current () on an electrical transmission line with distance and time. They were developed by Oliver Heaviside who created the transmission line model, and are based on Maxwell's Equations.

The transmission line model represents the transmission line as an infinite series of two-port elementary components, each representing an infinitesimally short segment of the transmission line:

- The distributed resistance of the conductors is represented by a series resistor (expressed in Ohms per unit length).

- The distributed inductance (due to the magnetic field around the wires, self-inductance, etc.) is represented by a series inductor (in Henries per unit length).

- The capacitance between the two conductors is represented by a shunt capacitor (in farads per unit length).

- The conductance of the dielectric material separating the two conductors is represented by a shunt resistor between the signal wire and the return wire (in siemens per unit length).

The model consists of an infinite series of the elements shown in the figure, and the values of the components are specified per unit length so the picture of the component can be misleading. , , , and may also be functions of frequency. An alternative notation is to use , , and to emphasize that the values are derivatives with respect to length. These quantities can also be known as the primary line constants to distinguish from the secondary line constants derived from them, these being the propagation constant, attenuation constant and phase constant.

The line voltage and the current can be expressed in the frequency domain as

When the elements and are negligibly small the transmission line is considered as a lossless structure. In this hypothetical case, the model depends only on the and elements which greatly simplifies the analysis. For a lossless transmission line, the second order steady-state Telegrapher's equations are:

These are wave equations which have plane waves with equal propagation speed in the forward and reverse directions as solutions. The physical significance of this is that electromagnetic waves propagate down transmission lines and in general, there is a reflected component that interferes with the original signal. These equations are fundamental to transmission line theory.

If and are included, the Telegrapher's equations become:

where is the propagation constant

and the characteristic impedance can be expressed as

The solutions for and are:

The constants must be determined from boundary conditions. For a voltage pulse , starting at and moving in the positive direction, then the transmitted pulse at position can be obtained by computing the Fourier Transform, , of , attenuating each frequency component by , advancing its phase by , and taking the inverse Fourier Transform. The real and imaginary parts of can be computed as

where atan2 is the two-parameter arctangent, and

For small losses and high frequencies, to first order in and one obtains

Noting that an advance in phase by is equivalent to a time delay by , can be simply computed as

Input impedance of transmission line

The characteristic impedance Z0 of a transmission line is the ratio of the amplitude of a single voltage wave to its current wave. Since most transmission lines also have a reflected wave, the characteristic impedance is generally not the impedance that is measured on the line.

The impedance measured at a given distance, l, from the load impedance ZL may be expressed as,

- ,

where γ is the propagation constant and is the voltage reflection coefficient at the load end of the transmission line. Alternatively, the above formula can be rearranged to express the input impedance in terms of the load impedance rather than the load voltage reflection coefficient:

- .

Input impedance of lossless transmission line

For a lossless transmission line, the propagation constant is purely imaginary, γ=jβ, so the above formulas can be rewritten as,

where is the wavenumber.

In calculating β, the wavelength is generally different inside the transmission line to what it would be in free-space and the velocity constant of the material the transmission line is made of needs to be taken into account when doing such a calculation.

Special cases of lossless transmission lines

Half wave length

For the special case where where n is an integer (meaning that the length of the line is a multiple of half a wavelength), the expression reduces to the load impedance so that

for all n. This includes the case when n=0, meaning that the length of the transmission line is negligibly small compared to the wavelength. The physical significance of this is that the transmission line can be ignored (i.e. treated as a wire) in either case.

Quarter wave length

For the case where the length of the line is one quarter wavelength long, or an odd multiple of a quarter wavelength long, the input impedance becomes

Matched load

Another special case is when the load impedance is equal to the characteristic impedance of the line (i.e. the line is matched), in which case the impedance reduces to the characteristic impedance of the line so that

for all and all .

Short

For the case of a shorted load (i.e. ), the input impedance is purely imaginary and a periodic function of position and wavelength (frequency)

Open

For the case of an open load (i.e. ), the input impedance is once again imaginary and periodic

Stepped transmission line

A stepped transmission line[8] is used for broad range impedance matching. It can be considered as multiple transmission line segments connected in series, with the characteristic impedance of each individual element to be Z0,i. The input impedance can be obtained from the successive application of the chain relation

where is the wave number of the ith transmission line segment and li is the length of this segment, and Zi is the front-end impedance that loads the ith segment.

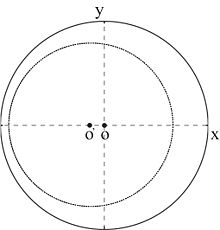

Because the characteristic impedance of each transmission line segment Z0,i is often different from that of the input cable Z0, the impedance transformation circle is off-centred along the x axis of the Smith Chart whose impedance representation is usually normalized against Z0.

Practical types

Coaxial cable

Coaxial lines confine virtually all of the electromagnetic wave to the area inside the cable. Coaxial lines can therefore be bent and twisted (subject to limits) without negative effects, and they can be strapped to conductive supports without inducing unwanted currents in them. In radio-frequency applications up to a few gigahertz, the wave propagates in the transverse electric and magnetic mode (TEM) only, which means that the electric and magnetic fields are both perpendicular to the direction of propagation (the electric field is radial, and the magnetic field is circumferential). However, at frequencies for which the wavelength (in the dielectric) is significantly shorter than the circumference of the cable, transverse electric (TE) and transverse magnetic (TM) waveguide modes can also propagate. When more than one mode can exist, bends and other irregularities in the cable geometry can cause power to be transferred from one mode to another.

The most common use for coaxial cables is for television and other signals with bandwidth of multiple megahertz. In the middle 20th century they carried long distance telephone connections.

Microstrip

A microstrip circuit uses a thin flat conductor which is parallel to a ground plane. Microstrip can be made by having a strip of copper on one side of a printed circuit board (PCB) or ceramic substrate while the other side is a continuous ground plane. The width of the strip, the thickness of the insulating layer (PCB or ceramic) and the dielectric constant of the insulating layer determine the characteristic impedance. Microstrip is an open structure whereas coaxial cable is a closed structure.

Stripline

A stripline circuit uses a flat strip of metal which is sandwiched between two parallel ground planes. The insulating material of the substrate forms a dielectric. The width of the strip, the thickness of the substrate and the relative permittivity of the substrate determine the characteristic impedance of the strip which is a transmission line.

Balanced lines

A balanced line is a transmission line consisting of two conductors of the same type, and equal impedance to ground and other circuits. There are many formats of balanced lines, amongst the most common are twisted pair, star quad and twin-lead.

Twisted pair

Twisted pairs are commonly used for terrestrial telephone communications. In such cables, many pairs are grouped together in a single cable, from two to several thousand.[9] The format is also used for data network distribution inside buildings, but the cable is more expensive because the transmission line parameters are tightly controlled.

Star quad

Star quad is a four-conductor cable in which all four conductors are twisted together around the cable axis. It is sometimes used for two circuits, such as 4-wire telephony and other telecommunications applications. In this configuration each pair uses two non-adjacent conductors. Other times it is used for a single, balanced line, such as audio applications and 2-wire telephony. In this configuration two non-adjacent conductors are terminated together at both ends of the cable, and the other two conductors are also terminated together.

When used for two circuits, crosstalk is reduced relative to cables with two separate twisted pairs.

When used for a single, balanced line, magnetic interference picked up by the cable arrives as a virtually perfect common mode signal, which is easily removed by coupling transformers.

The combined benefits of twisting, balanced signalling, and quadrupole pattern give outstanding noise immunity, especially advantageous for low signal level applications such as microphone cables, even when installed very close to a power cable.[10][11][12][13][14] The disadvantage is that star quad, in combining two conductors, typically has double the capacitance of similar two-conductor twisted and shielded audio cable. High capacitance causes increasing distortion and greater loss of high frequencies as distance increases.[15][16]

Twin-lead

Twin-lead consists of a pair of conductors held apart by a continuous insulator. By holding the conductors a known distance apart, the geometry is fixed and the line characteristics are reliably consistent. It is lower loss than coaxial cable because the wave propagates mostly in air rather than the thin dielectric. However, it is more susceptible to interference.

Lecher lines

Lecher lines are a form of parallel conductor that can be used at UHF for creating resonant circuits. They are a convenient practical format that fills the gap between lumped components (used at HF/VHF) and resonant cavities (used at UHF/SHF).

Single-wire line

Unbalanced lines were formerly much used for telegraph transmission, but this form of communication has now fallen into disuse. Cables are similar to twisted pair in that many cores are bundled into the same cable but only one conductor is provided per circuit and there is no twisting. All the circuits on the same route use a common path for the return current (earth return). There is a power transmission version of single-wire earth return in use in many locations.

General applications

Signal transfer

Electrical transmission lines are very widely used to transmit high frequency signals over long or short distances with minimum power loss. One familiar example is the down lead from a TV or radio aerial to the receiver.

Pulse generation

Transmission lines are also used as pulse generators. By charging the transmission line and then discharging it into a resistive load, a rectangular pulse equal in length to twice the electrical length of the line can be obtained, although with half the voltage. A Blumlein transmission line is a related pulse forming device that overcomes this limitation. These are sometimes used as the pulsed power sources for radar transmitters and other devices.

Stub filters

If a short-circuited or open-circuited transmission line is wired in parallel with a line used to transfer signals from point A to point B, then it will function as a filter. The method for making stubs is similar to the method for using Lecher lines for crude frequency measurement, but it is 'working backwards'. One method recommended in the RSGB's radiocommunication handbook is to take an open-circuited length of transmission line wired in parallel with the feeder delivering signals from an aerial. By cutting the free end of the transmission line, a minimum in the strength of the signal observed at a receiver can be found. At this stage the stub filter will reject this frequency and the odd harmonics, but if the free end of the stub is shorted then the stub will become a filter rejecting the even harmonics.

Acoustic transmission lines

An acoustic transmission line is the acoustic analogue of the electrical transmission line, typically thought of as a rigid-walled tube that is long and thin relative to the wavelength of sound present in it.

See also

References

Part of this article was derived from Federal Standard 1037C.

- ^ a b c Jackman, Shawn M.; Matt Swartz; Marcus Burton; Thomas W. Head (2011). CWDP Certified Wireless Design Professional Official Study Guide: Exam PW0-250. John Wiley & Sons. pp. Ch. 7. ISBN 1118041615.

- ^ a b Oklobdzija, Vojin G.; Ram K. Krishnamurthy (2006). High-Performance Energy-Efficient Microprocessor Design. Springer. p. 297. ISBN 0387340475.

- ^ Guru, Bhag Singh; Hüseyin R. Hızıroğlu (2004). Electromagnetic Field Theory Fundamentals, 2nd Ed. Cambridge Univ. Press. pp. 422–423. ISBN 1139451928.

- ^ Schmitt, Ron Schmitt (2002). Electromagnetics Explained: A Handbook for Wireless/ RF, EMC, and High-Speed Electronics. Newnes. p. 153. ISBN 0080505236.

- ^ Carr, Joseph J. (1997). Microwave & Wireless Communications Technology. USA: Newnes. pp. 46–47. ISBN 0750697075.

- ^ a b c d Raisanen, Antti V.; Arto Lehto (2003). Radio Engineering for Wireless Communication and Sensor Applications. Artech House. pp. 35–37. ISBN 1580536697.

- ^ Ernst Weber and Frederik Nebeker, The Evolution of Electrical Engineering, IEEE Press, Piscataway, New Jersey USA, 1994 ISBN 0-7803-1066-7

- ^ "Journal of Magnetic Resonance – Impedance matching with an adjustable segmented transmission line". Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 199: 104–110. doi:10.1016/j.jmr.2009.04.005.

- ^ Syed V. Ahamed, Victor B. Lawrence, Design and engineering of intelligent communication systems, pp.130-131, Springer, 1997 ISBN 0-7923-9870-X.

- ^ The Importance of Star-Quad Microphone Cable

- ^ Evaluating Microphone Cable Performance & Specifications

- ^ The Star Quad Story

- ^ What's Special About Star-Quad Cable?

- ^ How Starquad Works

- ^ Lampen, Stephen H. (2002). Audio/Video Cable Installer's Pocket Guide. McGraw-Hill. pp. 32, 110, 112. ISBN 0071386211.

- ^ Rayburn, Ray (2011). Eargle's The Microphone Book: From Mono to Stereo to Surround – A Guide to Microphone Design and Application (3 ed.). Focal Press. pp. 164–166. ISBN 0240820754.

- Steinmetz, Charles Proteus (August 27, 1898), "The Natural Period of a Transmission Line and the Frequency of lightning Discharge Therefrom", The Electrical World: 203–205

- Grant, I. S.; Phillips, W. R., Electromagnetism (2nd ed.), John Wiley, ISBN 0-471-92712-0

- Ulaby, F. T., Fundamentals of Applied Electromagnetics (2004 media ed.), Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-185089-X

- "Chapter 17", Radio communication handbook, Radio Society of Great Britain, 1982, p. 20, ISBN 0-900612-58-4

- Naredo, J. L.; Soudack, A. C.; Marti, J. R. (Jan 1995), "Simulation of transients on transmission lines with corona via the method of characteristics", IEE Proceedings. Generation, Transmission and Distribution., 142 (1), Morelos: Institution of Electrical Engineers, ISSN 1350-2360

Further reading

- Annual Dinner of the Institute at the Waldorf-Astoria. Transactions of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, New York, January 13, 1902. (Honoring of Guglielmo Marconi, January 13, 1902)

- Avant! software, Using Transmission Line Equations and Parameters. Star-Hspice Manual, June 2001.

- Cornille, P, On the propagation of inhomogeneous waves. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 23, February 14, 1990. (Concept of inhomogeneous waves propagation — Show the importance of the telegrapher's equation with Heaviside's condition.)

- Farlow, S.J., Partial differential equations for scientists and engineers. J. Wiley and Sons, 1982, p. 126. ISBN 0-471-08639-8.

- Kupershmidt, Boris A., Remarks on random evolutions in Hamiltonian representation. Math-ph/9810020. J. Nonlinear Math. Phys. 5 (1998), no. 4, 383-395.

- Transmission line matching. EIE403: High Frequency Circuit Design. Department of Electronic and Information Engineering, Hong Kong Polytechnic University. (PDF format)

- Wilson, B. (2005, October 19). Telegrapher's Equations. Connexions.

- John Greaton Wöhlbier, ""Fundamental Equation" and "Transforming the Telegrapher's Equations". Modeling and Analysis of a Traveling Wave Under Multitone Excitation.

- Agilent Technologies. Educational Resources. Wave Propagation along a Transmission Line. Edutactional Java Applet.

- Qian, C., Impedance matching with adjustable segmented transmission line. J. Mag. Reson. 199 (2009), 104–110.

![{\displaystyle a\equiv \omega ^{2}L\,C\,\left[\left({\frac {R}{\omega L}}\right)\left({\frac {G}{\omega C}}\right)-1\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7f940dd045448cbc3abe047d3db8e49722633555)