Standing on the shoulders of giants: Difference between revisions

Reverted to revision 737267336 by Brandmeister (talk): Remove random edit. (TW) |

|||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

==Attribution and meaning== |

==Attribution and meaning== |

||

Isaac also said it in 1663 |

|||

The attribution to Bernard is due to [[John of Salisbury]]. In 1159, John wrote in his ''Metalogicon'': "Bernard of Chartres used to compare us to dwarfs perched on the shoulders of giants. He pointed out that we see more and farther than our predecessors, not because we have keener vision or greater height, but because we are lifted up and borne aloft on their gigantic stature." <ref name="MacGarry Metalogicon">{{cite book |

The attribution to Bernard is due to [[John of Salisbury]]. In 1159, John wrote in his ''Metalogicon'': "Bernard of Chartres used to compare us to dwarfs perched on the shoulders of giants. He pointed out that we see more and farther than our predecessors, not because we have keener vision or greater height, but because we are lifted up and borne aloft on their gigantic stature." <ref name="MacGarry Metalogicon">{{cite book |

||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pA3VbvUf67EC&lpg=PA167&ots=73r28_CEGY&pg=PA167#v=onepage&q=&f=false |

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pA3VbvUf67EC&lpg=PA167&ots=73r28_CEGY&pg=PA167#v=onepage&q=&f=false |

||

Revision as of 22:35, 12 September 2016

The metaphor of dwarfs standing on the shoulders of giants (Template:Lang-la) expresses the meaning of "discovering truth by building on previous discoveries".[1] This concept has been traced to the 12th century, attributed to Bernard of Chartres. Its most familiar expression in English is by Isaac Newton in 1676: "If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants."[2]

Attribution and meaning

The attribution to Bernard is due to John of Salisbury. In 1159, John wrote in his Metalogicon: "Bernard of Chartres used to compare us to dwarfs perched on the shoulders of giants. He pointed out that we see more and farther than our predecessors, not because we have keener vision or greater height, but because we are lifted up and borne aloft on their gigantic stature." [3][4][page needed]

According to medieval historian Richard William Southern, Bernard was comparing the modern scholar (12th century) to the ancient scholars of Greece and Rome:[5]

[The phrase] sums up the quality of the cathedral schools in the history of learning, and indeed characterizes the age which opened with Gerbert (950–1003) and Fulbert (960–1028) and closed in the first quarter of the 12th century with Peter Abelard. [The phrase] is not a great claim; neither, however, is it an example of abasement before the shrine of antiquity. It is a very shrewd and just remark, and the important and original point was the dwarf could see a little further than the giant. That this was possible was above all due to the cathedral schools with their lack of a well-rooted tradition and their freedom from a clearly defined routine of study.

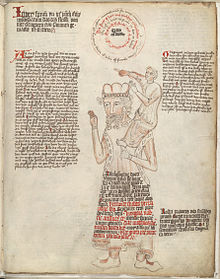

The visual image (from Bernard of Chartres) appears in the stained glass of the south transept of Chartres Cathedral. The tall windows under the Rose Window show the four major prophets of the Hebrew Bible (Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel) as gigantic figures, and the four New Testament evangelists (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) as ordinary-size people sitting on their shoulders. The evangelists, though smaller, "see more" than the huge prophets (since they saw the Messiah about whom the prophets spoke).

The phrase also appears in the works of the Jewish tosaphist Isaiah di Trani (c. 1180 – c. 1250):[6]

Should Joshua the son of Nun endorse a mistaken position, I would reject it out of hand, I do not hesitate to express my opinion, regarding such matters in accordance with the modicum of intelligence allotted to me. I was never arrogant claiming "My Wisdom served me well". Instead I applied to myself the parable of the philosophers. For I heard the following from the philosophers, The wisest of the philosophers asked: "We admit that our predecessors were wiser than we. At the same time we criticize their comments, often rejecting them and claiming that the truth rests with us. How is this possible?" The wise philosopher responded: "Who sees further a dwarf or a giant? Surely a giant for his eyes are situated at a higher level than those of the dwarf. But if the dwarf is placed on the shoulders of the giant who sees further? ... So too we are dwarfs astride the shoulders of giants. We master their wisdom and move beyond it. Due to their wisdom we grow wise and are able to say all that we say, but not because we are greater than they.

References during the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries

Diego de Estella took up the quote in the 16th century; by the 17th century it had become commonplace. Robert Burton, in The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621), quotes Stella thus:

I say with Didacus Stella, a dwarf standing on the shoulders of a giant may see farther than a giant himself.

Later editors of Burton misattributed the quote to Lucan; in their hands Burton's attribution Didacus Stella, in luc 10, tom. ii "Didacus on the Gospel of Luke, chapter 10; volume 2" became a reference to Lucan's Pharsalia 2.10. No reference or allusion to the quote is found there.

Later in the 17th century, George Herbert, in his Jacula Prudentum (1651), wrote "A dwarf on a giant's shoulders sees farther of the two."

Isaac Newton remarked in a letter to his rival Robert Hooke dated February 5, 1676 [O.S.][7] (February 15, 1676 [N.S.]) that:

What Des-Cartes [sic] did was a good step. You have added much several ways, & especially in taking the colours of thin plates into philosophical consideration. If I have seen further it is by standing on the sholders [sic] of Giants.

This has recently been interpreted by a few writers as a sarcastic remark directed at Hooke's appearance.[8] Although Hooke was not of particularly short stature, he was of slight build and had been afflicted from his youth with a severe kyphosis. However, at this time Hooke and Newton were on good terms and had exchanged many letters in tones of mutual regard. Only later, when Robert Hooke criticized some of Newton's ideas regarding optics, Newton was so offended that he withdrew from public debate, and the two men remained enemies until Hooke's death.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, in The Friend (1828), wrote:

The dwarf sees farther than the giant, when he has the giant's shoulder to mount on.

Against this notion, Friedrich Nietzsche argues that a dwarf (the academic scholar) brings even the most sublime heights down to his level of understanding. In the section of Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1882) entitled "On the Vision and the Riddle", Zarathustra climbs to great heights with a dwarf on his shoulders to show him his greatest thought. Once there however, the dwarf fails to understand the profundity of the vision and Zarathustra reproaches him for "making things too easy on [him]self." If there is to be anything resembling "progress" in the history of philosophy, Nietzsche in "Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks" (1873) writes, it can only come from those rare giants among men, "each giant calling to his brother through the desolate intervals of time," an idea he got from Schopenhauer's work in Der handschriftliche Nachlass.[9]

Contemporary references

- The British two pound coin bears the inscription STANDING ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS on its edge; this is intended as a quotation of Newton.[10]

- Google Scholar has adopted "Stand on the shoulders of giants" as its motto.

- In Umberto Eco's novel, The Name of the Rose, William of Baskerville utters the words when speaking to Nicholas of Morimondo, the master glazier at the monastery. Nicholas says about his art: "We no longer have the learning of the ancients, the age of giants is past!", to which William replies: "We are dwarfs, but dwarfs who stand on the shoulders of those giants, and small though we are, we sometimes manage to see farther on the horizon than they."

- Linux Mint installation slideshow has a slide titled "Standing on the shoulder of giants" meaning Ubuntu, Debian and GNU.

- It is referenced by Mark Zuckerberg, played by Jesse Eisenberg, in the 2010 film The Social Network.

- The fourth studio album from British rock band Oasis is titled "Standing on the Shoulder of Giants". Songwriter Noel Gallagher chose the name after reading it printed on the edge of a £2 coin; he scribbled the phrase down but spelled it incorrectly with the word 'Shoulder' rather than 'Shoulders' as he was inebriated at the time.

- In Jurassic Park, Dr. Ian Malcolm argues that John Hammond's research and advancement in the field of genetics was based on the work of those before him, limiting his responsibility in whatever happens, stating: "You stood on the shoulders of geniuses to accomplish something as fast as you could..."

- The The X-Files episode "Roland" features a scientist murdering his former colleagues from beyond the grave for taking credit for his research. At the final confrontation, the thieving scientist remarks "If I have seen further than other men, it's because I have stood on the shoulders of giants."

- Stephen Hawking's compilation of works by Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, Newton, and Einstein is entitled On The Shoulders of Giants. The Great Works of Physics and Astronomy, (Running Press 2002) ISBN 0-7624-1698-X.

- The American rock band R.E.M. uses the phrase "Standing on the shoulders of giants leaves me cold" in the song "King of Birds" from their fifth studio album Document.

- The American jazz and rock drummer Steve Smith wrote and produced an educational video package titled Drum Legacy - Standing on the Shoulders of Giants that traces the development of modern drumming from the concepts and techniques of earlier generations of musicians.

- On Giant's Shoulders, a 1979 BBC television film about the early life of thalidomide victim Terry Wiles.

- In the video game Portal 2, Cave Johnson states "They say great science is built on the shoulders of giants. Not here. At Aperture, we do all our science from scratch. No hand holding.".

- The metaphor of "standing on the shoulder of giants" is often used to promote and validate the free software movement. In the book Free as in Freedom, Bob Young of Red Hat supports the free software movement by saying that it enables people to stand on the shoulders of giants. He also says that standing on the shoulders of giants is the opposite of reinventing the wheel.[11]

- In the show The Big Bang Theory, when Sheldon Cooper (played by Jim Parsons) invites Professor Proton, Professor Proton is frustrated that nobody takes him seriously in the field of science because of his former role as a children's entertainer. Sheldon then proceeds to tell him that through his childhood, he was inspired to go into a scientific field thanks to Professor Proton's appearance on his TV show. Sheldon then proceeds to tell him that, if this is true of several other individuals that are Sheldon's age, then an entire generation of young scientists is standing on Professor Proton's shoulders.

- The Lubavitcher Rebbe said that our generation is compared to "dwarves standing on giants' shoulders". Although we may appear to be on a lower spiritual level (dwarves) than previous generations (who were like giants on a spiritual level), when our (much smaller) achievements are added to their (much larger) acievements, the combined achievements ultimately bring us to the era of Moshiach![12]

See also

References

- ^ Keith, Bonnie (2016). "Strategic Sourcing in the New Economy". Google Books. Palgrave McMillian. Retrieved August 15, 2016.

- ^ Newton, Isaac. "Letter from Sir Isaac Newton to Robert Hooke". Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ MacGarry, Daniel Doyle, ed. (1955). The Metalogicon of John Salisbury: A Twelfth-century Defense of the Verbal and Logical Arts of the Trivium. Translated by MacGarry, Daniel Doyle. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 167. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ^ See Merton, Robert K. (1965). On the Shoulders of Giants: A Shandean Postscript. Free Press.

- ^ Southern, Richard William (1952). Making of the Middle Ages. Yale University Press. p. 203.

- ^ Teshuvot (responsa) haRid 301–303. See Shnayer Z. Leiman, Dwarfs on the Shoulders of Giants, Tradition Spring 1993

- ^ Turnbull, H.W. ed., 1959. The Correspondence of Isaac Newton: 1661-1675, Volume 1, London, UK: Published for the Royal Society at the University Press. p. 416

- ^ Crease, Robert P. (2008). The Great Equations: The hunt for cosmic beauty in numbers. Constable and Robinson. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-84529-281-2.

- ^ Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm, Keith Ansell-Pearson, and Duncan Large. "Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks." The Nietzsche Reader. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub., 2006. 101–13. Print.

- ^ "United Kingdom Two Pound Coin Design". Royal Mint. Retrieved 2009-01-04.

- ^ Williams, Sam (2002). Free as in freedom. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-0-596-00287-9.

- ^ http://www.chabad.org/parshah/article_cdo/aid/376112/jewish/Dwarves-on-Giants-Shoulders.htm