Caliph: Difference between revisions

ahmadiyyas are not muslims Tag: section blanking |

m Reverted edits by 80.195.176.248 (talk): unexplained content removal (HG) |

||

| Line 100: | Line 100: | ||

Prior to its reestablishment, occasional demonstrations were held calling for the reestablishment of the Caliphate. Organisations which call for the re-establishment of the Caliphate include [[Hizb ut-Tahrir]] and the [[Muslim Brotherhood]].<ref name="autogenerated1">Jay Tolson, "Caliph Wanted: Why An Old Islamic Institution Resonates With Many Muslims Today", ''U.S News & World Report'' 144.1 (January 14, 2008): 38-40.</ref> |

Prior to its reestablishment, occasional demonstrations were held calling for the reestablishment of the Caliphate. Organisations which call for the re-establishment of the Caliphate include [[Hizb ut-Tahrir]] and the [[Muslim Brotherhood]].<ref name="autogenerated1">Jay Tolson, "Caliph Wanted: Why An Old Islamic Institution Resonates With Many Muslims Today", ''U.S News & World Report'' 144.1 (January 14, 2008): 38-40.</ref> |

||

===Ahmadiyya Caliphate=== |

|||

{{main|Khalifatul Masih}} |

|||

The [[Ahmadiyya Muslim Community]], a [[messianism|messianic]] movement in Islam, ''believes'' that the [[Khalifatul Masih|Ahmadiyya Caliphate]] established after the passing of the community's founder [[Mirza Ghulam Ahmad]] is the re-establishment of the [[Rashidun Caliphate]] (The Rightly Guided Caliphs)<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.alislam.org/topics/khilafat/ | title=The Ahmadiyya Khalifat | accessdate=March 5, 2011}}</ref> as prophesized by Muhammad.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.alislam.org/egazette/updates/the-islamic-khilafat-its-rise-fall-and-re-emergence/ | title=The Islamic Khilafat – Its Rise, Fall, and Re-emergence | accessdate=March 8, 2011 | author=Ahmad, Rafi}}</ref> The current successor to Mirza Ghulam Ahmad is [[Khalifatul Masih]] V, [[Mirza Masroor Ahmad]] residing in [[London]], [[England]].<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.reviewofreligions.org/1772/editorial-68/ | title=Hadhrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad, Khalifatul Masih V | accessdate=March 9, 2011 | publisher=The Review of Religions}}</ref> |

|||

The Ahmadiyya community's Caliph (Khalifa) has overall authority in all religious and organizational matters. According to Ahmadis, it is not essential for a Muslim Caliph to be the head of a state but instead the spiritual and religious significance of the Caliph should be emphasized. The Ahmadiyya believe their community is about 10 to 20 million strong in 200 countries and territories of the world. |

|||

==Titular uses== |

==Titular uses== |

||

Revision as of 14:15, 15 November 2014

Caliph or khalifa is a title used for Islamic rulers who are considered political-religious leaders of the Islamic community of believers, and who rule in accordance with Islamic law. A state ruled by a caliph is a caliphate.

Following Muhammad's death in 632, the early leaders of the Muslim nation were called Khalifat Rasul Allah, the political successors to the messenger of God (referring to Muhammad). A calipha is either a female caliph or the wife or widow of a caliph. There was one known instance in history that a calipha ruled a Caliphate: Sitt al-Mulk was regent of the Fatimid Caliphate from 1021 to 1023. Some caliphas, such as Zaynab an-Nafzawiyyah and Al-Khayzuran bint Atta, wielded great influence in the courts of their husbands.

The term derives from the Arabic word khalīfah (خَليفة ⓘ), which means "successor", "steward", or "deputy".

Qur'an

The Qur'an uses the term khalifa twice. First, in al-Baqara 30, it refers to God creating humanity as his khalifa on Earth. Second, in Sad 26, it addresses King David as God's khalifa and reminds him of his obligation to rule with justice.[1]

Succession to Muhammad

| Caliphate خِلافة |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

In his book The Early Islamic Conquests (1981), Fred Donner argues that the standard Arabian practice at the time was for the prominent men of a kinship group, or tribe, to gather after a leader's death and elect a leader from amongst themselves. There was no specified procedure for this shura or consultation. Candidates were usually, but not necessarily, from the same lineage as the deceased leader. Capable men who would lead well were preferred over an ineffectual heir.

Sunni Muslims believe and confirm that Abu Bakr was chosen by the community and that this was the proper procedure. Sunnis further argue that a caliph should ideally be chosen by election or community consensus.

Shi'a Muslims believe that Ali, the son-in-law and cousin of Muhammad, was chosen by Muhammad as his spiritual and temporal successor as the Mawla (the Imam and the Caliph) of all Muslims at a place called al-Gadhir Khumm. Here Mohammad called upon the around 100,000 gathered returning pilgrims to give their bayah (oath of allegiance) to Ali in his very presence and thenceforth to proclaim the good news of Ali's succession to his (Muhammad's) leadership to all Muslims they should come across.

Word usage / etymology

The word "caliph" is derived from the Arabic word khalifa (خليفة ḫalīfah/[khalīfah] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized transliteration standard: allah (help)) meaning "successor", "substitute", or "lieutenant". In Matthew S. Gordon's The Rise of Islam, caliph is said to translate to "deputy (or representative) of God." It is used in the Quran to establish Adam's role as representative of God on earth. Khalifa is also used to describe the belief that man's role, in his real nature, is as khalifa or viceroy to Allah.[2] The word is also most commonly used for the Islamic leader of the Ummah; starting with Abu Bakr and his line of successors.

The first four Caliphs: Abu Bakr as-Siddiq, Umar ibn al-Khattab, Uthman ibn Affan, and Ali ibn Abi Talib are commonly known by Sunnis, mainly, as the Khulafā’ur-Rāshideen ("rightly guided successors") Caliphs.

It should be noted that in Indonesia, the term caliph traditionally has a looser meaning, and has been applied to numerous leaders. For example, the current sultan Hamengkubuwono X has 'caliph' in his title, but without serious meaning.

History

Succession and recognition

Sunni and Shi'a Muslims differ on the legitimacy of the reigns of the Rashidun Caliphs, the first four Caliphs. The Sunnis follow the Caliphates of all four, while the Shi'ites recognize only the Caliphate of Ali and the short Caliphate of his son Hasan. This schism occurred following the death of Muhammad.

According to Sunni beliefs, Muhammad gave no specific directions as to the choosing of his successor when he died. At this time there were two customary means of selecting a leader: having a hereditary leader for general purposes, and choosing someone with good qualities in times of crisis or opportunities for action.

While Sunni and Shia Islam differ sharply on the conduct of a caliph and the right relations between a leader and a community, they do not differ on the underlying theory of stewardship. Both abhor waste of natural resources in particular to show off or demonstrate power.

In the initial stages the latter way of choosing leadership prevailed among the leading companions of Muhammad. Abu Bakr was elected as the first caliph or successor to Muhammad, with the other companions of Muhammad giving an oath of allegiance to him. Those opposing this method thought that Ali, Muhammad's nearest relative, should have succeeded him. However the appointment of the next two caliphs varied from the election of Abu Bakr. On his deathbed, Abu Bakr appointed Umar as his successor without an election by the community of Believers. The oath, approving the appointment of Umar, was taken only by the Companions present in Medina at the time. This led to certain groups disputing the authority of Umar. Umar also altered the way his successor would be found. Before he was assassinated, Umar decided that his successor would come from a group of six. This group included Ali and Uthman, another companion of Muhammad. These six would have to establish from among themselves Umar's successor. Ultimately Uthman was chosen as Umar's successor, becoming the third Caliph. After the assassination of Uthman, Ali was elected as the fourth Caliph

Ali's caliphate and the rise of the Umayyad Dynasty

Ali's reign as Caliph was plagued by great turmoil and internal strife. Ali was faced with multiple rebellions and insurrections. The primary one came from a misunderstanding on the part of Mu'awiyah, the governor of Damascus, marking the beginning of the end of the Caliphs. The Persians, taking advantage of this, infiltrated the two armies and attacked the other army causing chaos and internal hatred between the Companions at the Battle of Siffin. The battle lasted several months, resulting in a stalemate. In order to avoid further bloodshed, Ali agreed to negotiate with Mu'awiyah. This caused a faction of approximately 4,000 people that would be known as the Kharijites, to abandon the fight. After defeating the Kharijites at the Battle of Nahrawan, Ali would later be assassinated by the Kharijite Ibn Muljam. Ali's son Hasan was elected as the next Caliph, but handed his title to Mu'awiyah a few months later. Mu'awiyah became the fifth Caliph, establishing the Umayyad Dynasty,[3] named after the great-grandfather of Uthman and Mu'awiyah, Umayya ibn Abd Shams.[4] (All Caliphs after Mu'awiyah aren't considered true caliphs from an islamic perspective, though it was used as a title afterwards.)

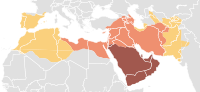

Umayyads

Under the Umayyads (661 to 750 AD, and 929 to 1031 in the Iberian Peninsula), the Muslim empire grew rapidly. To the West, Muslim rule expanded across North Africa and into Spain. To the East, it expanded through Iran and ultimately to India. This made it one of the largest empires in the history of West Eurasia, extending its entire breadth.

However, the Umayyad dynasty was not universally supported within Islam itself. Some Muslims supported prominent early Muslims like az-Zubayr; others felt that only members of Muhammad's clan, the Banū Hashim, or his own lineage, the descendants of ʻAlī, should rule. There were numerous rebellions against the Umayyads, as well as splits within the Umayyad ranks (notably, the rivalry between Yaman and Qays). Eventually, supporters of the Banu Hisham and Alid claims united to bring down the Umayyads in 750. However, the Shiʻat ʻAlī, "the Party of ʻAlī", were again disappointed when the Abbasid dynasty took power, as the Abbasids were descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib and not from ʻAlī.

Abbasids

The Abbasids would provide an unbroken line of rulers for over five centuries (750-1258 AD). It consolidated Islamic rule and cultivated great intellectual and cultural developments in the Middle East. But by 940 the power of the caliphate under the Abbasids was waning as non-Arabs, particularly the Turkish (and later the Mamluks in Egypt in the latter half of the 13th century), gained military power, and sultans and emirs became increasingly independent. However, the caliphate endured as both a symbolic position and a unifying entity for the Islamic world.

During the period of the Abbasid dynasty, Abbasid claims to the caliphate did not go unchallenged. The Shiʻa Said ibn Husayn of the Fatimid dynasty, which claimed descent from Muhammad through his daughter, claimed the title of Caliph in 909, creating a separate line of caliphs in North Africa. Initially covering Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya, the Fatimid caliphs extended their rule for the next 150 years, taking Egypt and the Levant, before the Abbasid dynasty was able to turn the tide, limiting Fatimid rule to Egypt. The Fatimid dynasty finally ended in 1171. The Umayyad dynasty, which had survived and come to rule over the Muslim provinces of Spain, reclaimed the title of Caliph in 929, lasting until it was overthrown in 1031. This period of upheaval was known as the Fitna of al-Ándalus.

Fatimids

The Fatimid Caliphate or al-Fātimiyyūn (Arabic الفاطميون) was a Berber Shi'ite dynasty that ruled over varying areas of the Maghreb, Egypt, Malta and the Levant from 5 January 909 to 1171, during the time that the (Sunni) Abbasid Caliphate ruled from Baghdad. The caliphate was ruled by the Fatimids, who established the Egyptian city of Cairo as their capital. The term Fatimite is sometimes used to refer to the citizens of this caliphate. The ruling elite of the state belonged to the Ismaili branch of Shi'ism. The leaders of the dynasty were also Shi'ite Ismaili religious tribes, hence, they had a religious significance to Ismaili Muslims. They are also part of the chain of holders of the title of Caliph, as recognized by Shi'ites majority. Therefore, this constitutes a rare period in history in which some form of Shi'ism and the title of Caliph were united to any degree. The Fatimids, however, are not recognized nor counted by the Sunnis as a caliphate.

With exceptions, the Fatimids were recorded to exercise a slight degree of tolerance towards non-Shi'ite sects of Islam, as well as towards Jews, Christians and pagans, due to the Shi'ite minority in every single land they conquered.[1]

Shadow Caliphate

1258 saw the conquest of Baghdad and the murder of the Abassid ruler al-Musta'sim by Mongol forces under Hulagu Khan. A surviving member of the Abbasid House was installed as Caliph at Cairo under the patronage of the Mamluk Sultanate three years later. However, the authority of this line of Caliphs was heavily restrained to ceremonial and religious matters, and Muslim historians refer to it as a "shadow" of Abbasid rule.[citation needed]

Ottomans

As the Ottoman Empire grew in size and strength, Ottoman rulers beginning with Mehmed II began to claim caliphal authority. Their claim was strengthened when the Ottomans defeated the Mamluks in 1517 and annexed the Arab lands. The last Abbasid ruler at Cairo, al-Mutawakkil III, became a political prisoner and was taken to Constantinople (conquered in 1453), where he was forced to surrender his authority to Selim I. However Ottoman rulers were known by the title of Sultan.

According to Barthold, the first time the title of caliph was used as a political instead of symbolic religious title by the Ottomans was in the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca ending the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774. The outcome of this war was disastrous for the Ottomans. Large territories, including those with large Muslim populations such as the Crimean Peninsula, were lost to the Christian Russian Empire. However, the Ottomans under Abdulhamid I claimed a diplomatic victory, the recognition of themselves as protectors of Muslims in Russia as part of the peace treaty. This was the first time the Ottoman caliph was acknowledged as having political significance outside of Ottoman borders by a European power. As a consequence of this diplomatic victory, as the Ottoman borders were shrinking, the powers of the Ottoman caliph increased.

Around 1880 Sultan Abdulhamid II reasserted the title as a way of countering creeping European colonialism in Muslim lands. His claim was most fervently accepted by the Barelwis of British India. By the eve of the First World War, the Ottoman state, despite its weakness vis-à-vis Europe, represented the largest and most powerful independent Islamic political entity. But the sultan also enjoyed[citation needed] some authority beyond the borders of his shrinking empire as caliph of Muslims in Egypt, India and Central Arabia.

Abolition of the institution

The Khilafat movement (1919–1924) was a pan-Islamic, political protest campaign launched by Muslims in British India to influence the British government and to protect the Ottoman Empire at the end of the First World War. After the Armistice of Mudros of October 1918 with the military occupation of Istanbul and Treaty of Versailles (1919), the position of the Ottomans was uncertain. The movement to protect or restore the Ottomans gained force after the Treaty of Sèvres (August 1920) which imposed the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire and gave Greece a powerful position in Anatolia, to the distress of the Turks. They called for help and the movement was the result. The movement had collapsed by late 1922.

The new ruler of Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, wanted a secular state. On 3 March 1924, the Turkish Grand National Assembly dissolved the institution of the Caliphate.

Prior to its reestablishment, occasional demonstrations were held calling for the reestablishment of the Caliphate. Organisations which call for the re-establishment of the Caliphate include Hizb ut-Tahrir and the Muslim Brotherhood.[5]

Ahmadiyya Caliphate

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, a messianic movement in Islam, believes that the Ahmadiyya Caliphate established after the passing of the community's founder Mirza Ghulam Ahmad is the re-establishment of the Rashidun Caliphate (The Rightly Guided Caliphs)[6] as prophesized by Muhammad.[7] The current successor to Mirza Ghulam Ahmad is Khalifatul Masih V, Mirza Masroor Ahmad residing in London, England.[8]

The Ahmadiyya community's Caliph (Khalifa) has overall authority in all religious and organizational matters. According to Ahmadis, it is not essential for a Muslim Caliph to be the head of a state but instead the spiritual and religious significance of the Caliph should be emphasized. The Ahmadiyya believe their community is about 10 to 20 million strong in 200 countries and territories of the world.

Titular uses

Religious leaders

- In 19th century Sudan, Mohammed Ahmed so-called "the Mahdi" was succeeded by Abdallahi ibn Muhammad "the Khalifa".

- In the Ahmadiyya sect, khalifatul Masih is the title of the successors of its founding Messiah, except in the break-away Lahore branch, which is led by its own Emirs.

Secular offices

In Morocco, the Sherifian Monarch awarded the title Khalifa or Chaliphe, here meaning 'Viceroy', to royal princes (styled Mulay), including future Sultans, who represented the crown in a part of the sultanate:

- especially in the former royal capitals Marrakesh, Fes and Meknes

- also in other mayor cities, e.g. in Shawiya, Casablanca, Tafilalt, Tadla, Tiznit Tindouf, in the valley of the Draa River and in Tetouan.

- but also, in the 20th century, as irrevocably fully mandated Representative of the Sultan in the Spanish Zone, known after him in Spanish as el Jalifato (note the definite article; although the Spanish word can also be applied to other deputies of various Moroccan officials), besides the Alto comisario (de facto governing 'High Commissioner') of the colonial 'protector' Spain, which called his office el Jalifa (not Califa, the word for any 'imperial' Caliph, ruling a califato):

- 19 April 1913 - 9 November 1923 Mulay al-Mahdi bin Isma'il bin Muhammad (d. 1923)

- 9 November 1923 - 9 November 1925 Vacant

- 9 November 1925 - 16 March 1941 Mulay Hassan bin al-Mahdi (1st time) (born 1912)

- 16 March 1941 - October 1945 Vacant

- October 1945 - 7 April 1956 Mulay Hassan bin al-Mahdi (2nd time)

Sokoto Caliphate

The leaders of Sokoto Caliphate have used the title Caliph (Amir al-Mu'minin) from 1804.

The Islamic State (ISIS)

On 29 June 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant declared the territories under its control (on the Iraq-Syria border) to be a new Caliphate, naming Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi as the Caliph. [9]

Authority of the successor

The question of who should succeed Muhammad was not the only issue that faced the early Muslims; they also had to clarify the extent of the leader's powers. Muhammad, during his lifetime, was not only the Muslim political leader, but the Islamic prophet. All law and spiritual practice proceeded from Muhammad. Nobody claimed that his successor would be a prophet; succession referred to political authority. The uncertainty centered on the extent of that authority. Muhammad's revelations from God were soon written down (the Qur'an), which was a supreme authority, limiting what any leader could legitimately command, though few "Caliphs" actually abided by it.

However, some later caliphs did believe that they had authority to rule in matters not specified in the Quran. They believed themselves to be temporal and spiritual leaders in issues not commanded in the Quran, and insisted that implicit obedience to the caliph in all things not contradicting the Quran, was the hallmark of the good Muslim. Patricia Crone and Martin Hinds, in their book God's Caliph, outline the evidence for an early, expansive view of the caliph's importance and authority. They argue that this view of the caliph was eventually nullified (in Sunni Islam, at least) by the rising power of the ulema, or Islamic lawyers, judges, scholars, and religious specialists. The ulema insisted on their right to determine what was legal and orthodox. The proper Muslim leader, in the ulema's opinion, was the leader who enforced the rulings of the ulema, rather than making rulings of his own, unless he himself was qualified in Islamic law. Conflict between caliph and ulema, akin to a modern judiciary, was a recurring theme in early Islamic history, and ended in the victory of the ulema. The caliph was henceforth limited to temporal rule only. He would be considered a righteous caliph if he were guided by the ulema. Crone and Hinds argue that Shi'a Muslims, with their expansive view of the powers of the imamate, have preserved some of the beliefs of the early Umayyad dynasty which ironically, they despise. Crone and Hinds' thesis is not accepted by the scholars, however, who have evidence that the reason behind this is that the Rashidun and Umayyad leaders were Ulema themselves.

Most Mainstream Muslims (non-Shi'ites) believe that the caliph has always been a merely temporal ruler, and that the ulema has always been responsible for enforcing orthodox, Islamic law (shari'a). As for the special role ascribed to the first four caliphs, Islamic tradition holds that they were followers the Qur'an and the way or sunnah of Muhammad in all things and, for this reason, calls them the Rashidun, the Rightly Guided Caliphs. They also believe that the Khilafah ended towards the end of Ali's reign and not with the fall of the Ottomans. Every Muslim leader after Ali and Muawiyah, they say, were not legitimate due to they not being accepted by all the Muslims. Caliphs are not a significant part of mainstream Islam as opposed to the Shi'ites.

Al-Ghazali on the desired character traits for administration

Al Ghazali's "Nasihat al-Muluk" or "Advice for Kings", part of the Nasîhatnâme genre, gave ten different ethics of royal administration:

- The ruler should understand the importance and danger of the authority entrusted to him. In authority there is great blessing, since he who exercises it righteously obtained unsurpassed happiness but if any ruler fails to do so he incurs torment (in the afterlife) surpassed only by the torment for unbelief.

- The ruler should always be thirsting to meet devout religious scholars and ask them for advice.

- The ruler should understand that he must not covet the wives of other men and be content with personally refraining from injustice, but must discipline his slave-troops, servants, and officers and never tolerate unjust conduct by them; for he will be interrogated (in the afterlife) not only about his own unjust deeds but also about those of his staff.

- The ruler should not be dominated by pride; for pride gives rise to the dominance of anger, and will impel him to revenge. Anger is the evil genius and blight of the intellect. If anger is becoming dominant it will be necessary for the ruler in all his affairs to bend his inclinations in the direction of forgiveness and make a habit of generosity and forbearance unless he is to be like the wild beasts.

- In every situation that arises, the ruler should figure that he is the subject and the other person is the holder of authority. He should not sanction for others anything that he would not sanction for himself. For if he would do so he would be making fraudulent and treasonable use of the authority entrusted to him.

- The ruler should not disregard the attendance of petitioners at his court and should beware of the danger of so doing. He should solve the grievances of the Muslims.

- The ruler should not form a habit of indulging the passions. Although he might dress more finely or eat more sumptuously, he should be content with all that he has; for without contentment, just conduct will not be possible.

- The ruler should make the utmost effort to behave gently and avoid governing harshly.

- The ruler should endeavor to keep all the subjects pleased with him. The ruler should not let himself be so deluded by the praise he gets from any who approach him as to believe that all the subjects are pleased with him. On the contrary, such praise is entirely due to fear. He must therefore appoint trustworthy persons to gather intelligence and inquire about his standing among the people, so that he may be able to learn his faults from men's tongues.

- The ruler should not give satisfaction to any person if a contravention of God's law would be required to please him for no harm will come from such a person's displeasure.

Single Caliph for the Muslim world

According to the Sahih Muslim hadith, Muhammad said:

The children of Israel have been governed by Prophets; whenever a Prophet died another Prophet succeeded him; but there will be no prophet after me. There will be caliphs and they will number many (in one time); they asked: What then do you order us? He said: Fulfil bayah to them, only the first of them, the first of them, and give them their dues; for verily Allah will ask them about what he entrusted them with[10]

According to the Sīrat Rasūl Allāh of Ibn Isḥaq, Abu-Bakr, Muhammad's closest friend, said:

It is forbidden for Muslims to have two Amirs for this would cause differences in their affairs and concepts, their unity would be divided and disputes would break out amongst them. The Sunnah would then be abandoned, the bida'a (innovations of rituals) would spread and Fitna would grow, and that is in no one's interests".[11]

Umar bin Al-Khattab another disciple of Muhammad is reported by the same source to have said: "There is no way for two (leaders) together at any one time"[11]

(Referring in the quotes above to two leaders in the same land.)

Imam Al-Nawawi a 12th-century authority of the Sunni Shafi'i madhhab said: "It is forbidden to give an oath to two caliphs or more, even in different parts of the world and even if they are far apart"[12]

Notable Caliphs

- Rashidun ("Righteously Guided")

- Abu Bakr, first Rashidun Caliph. Subdued rebel tribes in the Ridda wars.

- Umar (Umar ibn al-Khattab), second Rashidun Caliph. During his reign, the Islamic empire expanded to include Egypt, Jerusalem and Persia.

- Uthman Ibn Affan, third Rashidun Caliph. The various written copies of the Qur'an were standardized under his direction. Killed by rebels.

- Ali (Ali ibn Abu Talib), fourth Rashidun Caliph. Considered by Shi'a Muslims however to be the first Imam. His reign was fraught with internal conflict, with Muawiyah ibn Abi Sufyan (Muawiyah I) and Amr ibn al-As controlling the Levant and Egypt regions independently of Ali.

- Hasan ibn Ali, fifth Caliph. Considered as "rightly guided" by several historians. He abdicated his right to the caliphate in favour of Muawiyah I in order to end the potential for ruinous civil war.

- Muawiyah I, first caliph of the Umayyad dynasty. Muawiyah instituted dynastic rule by appointing his son Yazid I as his successor, a trend that would continue through subsequent caliphates.

- Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz (Umar II), Umayyad caliph who is considered one of the finest rulers in Muslim history. He is also considered by some (mainly Sunnis) to be among the "rightly guided" caliphs.

- Harun al-Rashid, Abbasid caliph during whose reign Baghdad became the world's prominent centre of trade, learning, and culture. Harun is the subject of many stories in the famous One Thousand and One Nights. He established the legendary library Bayt al-Hikma ("House of Wisdom").

- Al-Ma'mun, a great Abbasid patron of Islamic philosophy and science.

- Fatih Sultan Mehmed (Mehmed II), an Ottoman caliph highly regarded for his long succession of campaigns which resulted in a tremendous extension of direct Ottoman rule.

- Suleiman the Magnificent, an Ottoman caliph during whose reign the Ottoman Empire reached its zenith.

- Abdul Hamid II, last Ottoman caliph to rule with independent, absolute power.

- Abdülmecid II, last caliph of the Ottoman dynasty. Nominally the 37th Head of the Ottoman dynasty.

Several Arabic surnames found throughout the Middle East are derived from the word khalifa. These include: Khalif, Khalifa, Khillif, Kalif, Kalaf, Khalaf, and Kaylif. The usage of this title as a surname is comparable to the existence of surnames such as King, Duke, and Noble in the English language.

Dynasties

The more important dynasties include:

- The Umayyad dynasty in Damascus (661–750), followed by:

- The Abbasid dynasty in Baghdad (750–1258), and later in Cairo (under Mameluk control) (1260–1517).

- The Shi'ite Fatimid dynasty in North Africa and Egypt (909–1171).

- The Rahmanids, a surviving branch of the Damascus Umayyads, established "in exile" as emirs of Córdoba, Spain, declared themselves Caliphs (known as the Caliphs of Córdoba; not universally accepted; 929–1031).

- The Almohad dynasty in North Africa and Spain (not universally accepted; 1145–1269). Traced their descent not from Muhammad, but from a puritanic reformer in Morocco who claimed to be the Mahdi, bringing down the "decadent" Almoravid emirate, and whose son established a sultanate and claimed to be a caliph.

- The Ottomans rulers (1453–1924; main title Padishah, also known as Great Sultan etc.) claimed caliphal authority beginning with Mehmed II. Their claim was strengthened in 1517 when the Ottomans defeated the Mamluk Sultanate of Cairo and made Egypt part of the Ottoman Empire.

Note on the overlap of Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates: After the massacre of the Umayyad clan by the Abbassids, one lone prince escaped and fled to North Africa, which remained loyal to the Umayyads. This was Abd-ar-rahman I. From there, he proceeded to Spain, where he overthrew and united the provinces conquered by previous Umayyad Caliphs (in 712 and 712). From 756 to 929, this Umayyad domain in Spain was an independent emirate, until Abd-ar-rahman III reclaimed the title of Caliph for his dynasty. The Umayyad Emirs of Spain are not listed in the summary below because they did not claim the caliphate until 929. For a full listing of all the Umayyad rulers in Spain see the Umayyad article.

Claims to the caliphate

Many local rulers in Islamic countries have claimed to be caliphs. Most claims were ignored outside their limited domains. In many cases, these claims were made by rebels against established authorities and ended when the rebellion was crushed. Notable claimants include:

- Abd-Allah ibn al-Zubayr (died 692), who held the Tihamah and the Hijaz against the Umayyads. Certain scholars considered him a legitimate Caliph, being a close companion of Muhammad. His rebellion, centered in Mecca, was crushed by the Umayyad general Hajjaj. Hajjaj's attack caused some damage in Mecca, and necessitated the rebuilding of the Kaaba.

- Caliph of the Sudan, a Songhai king of the Sahel.

- The Zaydi Imams of Yemen used the title for centuries and continued to use the title until 1962.

- Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca, proclaimed himself Caliph of the Arabs on 3 March 1924, two days after the office was abolished by the Grand National Assembly of Turkey. (see Sharifian Caliphate) Hussein's claim was not accepted, and in 1925 he was driven from the Hijaz by the forces of Ibn Saud due to his lack of support for Shari'ah. He continued to use the title of Caliph during his remaining life in exile, until his death in 1931.

- Kartosuwiryo (died 1962), leader of the Darul Islam rebellion that aimed to establish a caliphate in Indonesia (and eventually the rest of South East Asia). While he seldom explicitly claimed to be caliph, he was regarded as one by many supporters.

See also

- Caliphate

- Worldwide Caliphate

- List of Caliphs

- Shi'ite Imams

- Amir al-Mu'minin

- Khalifatul Masih

- Sheikh ul-Islam

- Succession to Muhammad

- Mahdi

- Sokoto Caliphate

References

- ^ Sonn, Tamara (2010). Islam: A Brief History (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-4051-8094-8.

- ^ From the article "Khalifah" in Oxford Islamic Studies Online

- ^ The Concise Encyclopedia of Islam. Cyril Glasse. pp. 39-41,318-319, 353-354

- ^ Uthman was the son of `Affan, the son of Abu-l`As, the son of Umayya ibn Abd Shams. Mu'awiyah was the son of Abu Sufyan, the son of Harb, the son of Umayya ibn Abd Shams.

- ^ Jay Tolson, "Caliph Wanted: Why An Old Islamic Institution Resonates With Many Muslims Today", U.S News & World Report 144.1 (January 14, 2008): 38-40.

- ^ "The Ahmadiyya Khalifat". Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ Ahmad, Rafi. "The Islamic Khilafat – Its Rise, Fall, and Re-emergence". Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ "Hadhrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad, Khalifatul Masih V". The Review of Religions. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- ^ http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/isis-declares-new-islamic-state-in-middle-east-with-abu-bakr-albaghdadi-as-emir-removing-iraq-and-syria-from-its-name-9571374.html

- ^ Sahih Muslim, Kitab al-Imarah (Book of Government)

- ^ a b "As-Sirah" of Ibn Ishaq; on the day of Thaqifa

- ^ Mughni Al-Muhtaj, volume 4, page 132

Bibliography

- Arnold, T. W. (1993). "Khalīfa". In Houtsma, M. Th (ed.). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936. Vol. Volume IV. Leiden: BRILL. pp. 881–885. ISBN 978-90-04-09790-2.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|volume=has extra text (help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Crone, Patricia, and Martin Hinds. God's Caliph: Religious Authority in the First Centuries of Islam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986. ISBN 0-521-32185-9.

- Donner, Fred. The Early Islamic Conquests. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1981. ISBN 0-691-05327-8.