Decorator pattern: Difference between revisions

→Examples: Removed C#-example because it was not the decorator pattern (it was normal inheritance, and did not allow for more than one behaviour to be added). Only added to confusion. |

Photonique (talk | contribs) remove odd citation needed comment |

||

| Line 313: | Line 313: | ||

} |

} |

||

private: |

private: |

||

Coffee* basicCoffee_; // |

|||

Coffee* basicCoffee_; // {{citation needed|reason=Could this not go into a base Decorator interface for reuse?, See Java example above|date=September 2014}} |

|||

}; |

}; |

||

Revision as of 03:37, 14 September 2014

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2013) |

In object-oriented programming, the decorator pattern (also known as Wrapper, an alternative naming shared with the Adapter pattern) is a design pattern that allows behavior to be added to an individual object, either statically or dynamically, without affecting the behavior of other objects from the same class.[1]

Intent

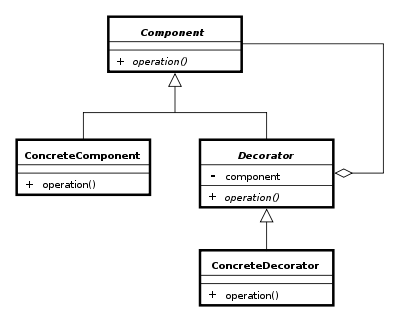

The decorator pattern can be used to extend (decorate) the functionality of a certain object statically, or in some cases at run-time, independently of other instances of the same class, provided some groundwork is done at design time. This is achieved by designing a new decorator class that wraps the original class. This wrapping could be achieved by the following sequence of steps:

- Subclass the original "Component" class into a "Decorator" class (see UML diagram);

- In the Decorator class, add a Component pointer as a field;

- Pass a Component to the Decorator constructor to initialize the Component pointer;

- In the Decorator class, redirect all "Component" methods to the "Component" pointer; and

- In the ConcreteDecorator class, override any Component method(s) whose behavior needs to be modified.

This pattern is designed so that multiple decorators can be stacked on top of each other, each time adding a new functionality to the overridden method(s).

Note that decorators and the original class object share a common set of features. In the previous diagram, the "operation()" method was available in both the decorated and undecorated versions.

The decoration features (e.g., methods, properties, or other members) are usually defined by an interface, mixin (a.k.a. "trait") or class inheritance which is shared by the decorators and the decorated object. In the previous example the class "Component" is inherited by both the "ConcreteComponent" and the subclasses that descend from "Decorator".

The decorator pattern is an alternative to subclassing. Subclassing adds behavior at compile time, and the change affects all instances of the original class; decorating can provide new behavior at run-time for individual objects.

This difference becomes most important when there are several independent ways of extending functionality. In some object-oriented programming languages, classes cannot be created at runtime, and it is typically not possible to predict, at design time, what combinations of extensions will be needed. This would mean that a new class would have to be made for every possible combination. By contrast, decorators are objects, created at runtime, and can be combined on a per-use basis. The I/O Streams implementations of both Java and the .NET Framework incorporate the decorator pattern.

Motivation

As an example, consider a window in a windowing system. To allow scrolling of the window's contents, we may wish to add horizontal or vertical scrollbars to it, as appropriate. Assume windows are represented by instances of the Window class, and assume this class has no functionality for adding scrollbars. We could create a subclass ScrollingWindow that provides them, or we could create a ScrollingWindowDecorator that adds this functionality to existing Window objects. At this point, either solution would be fine.

Now let's assume we also desire the ability to add borders to our windows. Again, our original Window class has no support. The ScrollingWindow subclass now poses a problem, because it has effectively created a new kind of window. If we wish to add border support to all windows, we must create subclasses WindowWithBorder and ScrollingWindowWithBorder. Obviously, this problem gets worse with every new feature to be added. For the decorator solution, we simply create a new BorderedWindowDecorator—at runtime, we can decorate existing windows with the ScrollingWindowDecorator or the BorderedWindowDecorator or both, as we see fit.

Note, in the previous example, that the "SimpleWindow" & "WindowDecorator" classes implement the "Window" interface, which defines the "draw();" method and the "getDescription();" method, that are required in this scenario, in order to decorate a window control.

Examples

Java

First example (window/scrolling scenario)

The following Java example illustrates the use of decorators using the window/scrolling scenario.

// The Window interface class

public interface Window {

public void draw(); // Draws the Window

public String getDescription(); // Returns a description of the Window

}

// Extension of a simple Window without any scrollbars

class SimpleWindow implements Window {

public void draw() {

// Draw window

}

public String getDescription() {

return "simple window";

}

}

The following classes contain the decorators for all Window classes, including the decorator classes themselves.

// abstract decorator class - note that it implements Window

abstract class WindowDecorator implements Window {

protected Window windowToBeDecorated; // the Window being decorated

public WindowDecorator (Window windowToBeDecorated) {

this.windowToBeDecorated = windowToBeDecorated;

}

public void draw() {

windowToBeDecorated.draw(); //Delegation

}

public String getDescription() {

return windowToBeDecorated.getDescription(); //Delegation

}

}

// The first concrete decorator which adds vertical scrollbar functionality

class VerticalScrollBarDecorator extends WindowDecorator {

public VerticalScrollBarDecorator (Window windowToBeDecorated) {

super(windowToBeDecorated);

}

@Override

public void draw() {

super.draw();

drawVerticalScrollBar();

}

private void drawVerticalScrollBar() {

// Draw the vertical scrollbar

}

@Override

public String getDescription() {

return super.getDescription() + ", including vertical scrollbars";

}

}

// The second concrete decorator which adds horizontal scrollbar functionality

class HorizontalScrollBarDecorator extends WindowDecorator {

public HorizontalScrollBarDecorator (Window windowToBeDecorated) {

super(windowToBeDecorated);

}

@Override

public void draw() {

super.draw();

drawHorizontalScrollBar();

}

private void drawHorizontalScrollBar() {

// Draw the horizontal scrollbar

}

@Override

public String getDescription() {

return super.getDescription() + ", including horizontal scrollbars";

}

}

Here's a test program that creates a Window instance which is fully decorated (i.e., with vertical and horizontal scrollbars), and prints its description:

public class DecoratedWindowTest {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Create a decorated Window with horizontal and vertical scrollbars

Window decoratedWindow = new HorizontalScrollBarDecorator (

new VerticalScrollBarDecorator (new SimpleWindow()));

// Print the Window's description

System.out.println(decoratedWindow.getDescription());

}

}

The output of this program is "simple window, including vertical scrollbars, including horizontal scrollbars". Notice how the getDescription method of the two decorators first retrieve the decorated Window's description and decorates it with a suffix.

Second example (coffee making scenario)

The next Java example illustrates the use of decorators using coffee making scenario. In this example, the scenario only includes cost and ingredients.

// The abstract Coffee class defines the functionality of Coffee implemented by decorator

public abstract class Coffee {

public abstract double getCost(); // Returns the cost of the coffee

public abstract String getIngredients(); // Returns the ingredients of the coffee

}

// Extension of a simple coffee without any extra ingredients

public class SimpleCoffee extends Coffee {

public double getCost() {

return 1;

}

public String getIngredients() {

return "Coffee";

}

}

The following classes contain the decorators for all Coffee classes, including the decorator classes themselves..

// Abstract decorator class - note that it extends Coffee abstract class

public abstract class CoffeeDecorator extends Coffee {

protected final Coffee decoratedCoffee;

protected String ingredientSeparator = ", ";

public CoffeeDecorator (Coffee decoratedCoffee) {

this.decoratedCoffee = decoratedCoffee;

}

public double getCost() { // Implementing methods of the abstract class

return decoratedCoffee.getCost();

}

public String getIngredients() {

return decoratedCoffee.getIngredients();

}

}

// Decorator Milk that mixes milk with coffee.

// Note it extends CoffeeDecorator.

class Milk extends CoffeeDecorator {

public Milk (Coffee decoratedCoffee) {

super(decoratedCoffee);

}

public double getCost() { // Overriding methods defined in the abstract superclass

return super.getCost() + 0.5;

}

public String getIngredients() {

return super.getIngredients() + ingredientSeparator + "Milk";

}

}

// Decorator Whip that mixes whip with coffee.

// Note it extends CoffeeDecorator.

class Whip extends CoffeeDecorator {

public Whip (Coffee decoratedCoffee) {

super(decoratedCoffee);

}

public double getCost() {

return super.getCost() + 0.7;

}

public String getIngredients() {

return super.getIngredients() + ingredientSeparator + "Whip";

}

}

// Decorator Sprinkles that mixes sprinkles with coffee.

// Note it extends CoffeeDecorator.

class Sprinkles extends CoffeeDecorator {

public Sprinkles (Coffee decoratedCoffee) {

super(decoratedCoffee);

}

public double getCost() {

return super.getCost() + 0.2;

}

public String getIngredients() {

return super.getIngredients() + ingredientSeparator + "Sprinkles";

}

}

Here's a test program that creates a Coffee instance which is fully decorated (i.e., with milk, whip, sprinkles), and calculate cost of coffee and prints its ingredients:

public class Main {

public static final void main(String[] args) {

Coffee c = new SimpleCoffee();

System.out.println("Cost: " + c.getCost() + "; Ingredients: " + c.getIngredients());

c = new Milk(c);

System.out.println("Cost: " + c.getCost() + "; Ingredients: " + c.getIngredients());

c = new Sprinkles(c);

System.out.println("Cost: " + c.getCost() + "; Ingredients: " + c.getIngredients());

c = new Whip(c);

System.out.println("Cost: " + c.getCost() + "; Ingredients: " + c.getIngredients());

// Note that you can also stack more than one decorator of the same type

c = new Sprinkles(c);

System.out.println("Cost: " + c.getCost() + "; Ingredients: " + c.getIngredients());

}

}

The output of this program is given below:

Cost: 1.0; Ingredients: Coffee Cost: 1.5; Ingredients: Coffee, Milk Cost: 1.7; Ingredients: Coffee, Milk, Sprinkles Cost: 2.4; Ingredients: Coffee, Milk, Sprinkles, Whip Cost: 2.6; Ingredients: Coffee, Milk, Sprinkles, Whip, Sprinkles

C++

Here is an example program written in C++:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

/* Abstract base class */

// The abstract Coffee class defines the functionality of Coffee implemented by decorator

class Coffee {

public:

virtual double getCost() = 0; // Returns the cost of the coffee

virtual std::string getIngredients() = 0; // Returns the ingredients of the coffee

virtual ~Coffee() = 0;

};

inline Coffee::~Coffee(){}

/* SimpleCoffee class. */

// Extension of a simple coffee without any extra ingredients

class SimpleCoffee : public Coffee {

public: //Added 3/4/14 after trying to run on VSPRO2012, adding public fixed errors.

double getCost() {

return 1.0;

}

std::string getIngredients() {

return "Coffee";

}

};

/* Decorators */

// Decorator Milk that adds milk to coffee.

struct MilkDecorator : Coffee {

public:

MilkDecorator (Coffee* basicCoffee)

:basicCoffee_(basicCoffee) {

}

double getCost() { // Providing methods defined in the abstract superclass

return basicCoffee_->getCost() + 0.5;

}

std::string getIngredients() {

return basicCoffee_->getIngredients() + ", " + "Milk";

}

private:

Coffee* basicCoffee_; //

};

// Decorator Whip that adds whip to coffee

struct WhipDecorator : Coffee {

public:

WhipDecorator (Coffee* basicCoffee)

:basicCoffee_(basicCoffee) {

}

double getCost() {

return basicCoffee_->getCost() + 0.7;

}

std::string getIngredients() {

return basicCoffee_->getIngredients() + ", " + "Whip";

}

private:

Coffee* basicCoffee_; // {{citation needed|reason=Could this not go into a base Decorator interface for reuse?, See Java example above|date=September 2014}}

};

/* Test program */

int main()

{

SimpleCoffee s;

std::cout << "Cost: " << s.getCost() << "; Ingredients: " << s.getIngredients() << std::endl;

MilkDecorator m(&s);

std::cout << "Cost: " << m.getCost() << "; Ingredients: " << m.getIngredients() << std::endl;

WhipDecorator w(&s);

std::cout << "Cost: " << w.getCost() << "; Ingredients: " << w.getIngredients() << std::endl;

// Note that you can stack decorators:

MilkDecorator m2(&w);

std::cout << "Cost: " << m2.getCost() << "; Ingredients: " << m2.getIngredients() << std::endl;

}

The output of this program is given below:

Cost: 1.0; Ingredients: Coffee Cost: 1.5; Ingredients: Coffee, Milk Cost: 1.7; Ingredients: Coffee, Whip Cost: 2.2; Ingredients: Coffee, Whip, Milk

Dynamic languages

The decorator pattern can also be implemented in dynamic languages either with interfaces or with traditional OOP inheritance.

See also

- Composite pattern

- Adapter pattern

- Abstract class

- Abstract factory

- Aspect-oriented programming

- Immutable object

References

- ^ Gamma, Erich; et al. (1995). Design Patterns. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co, Inc. pp. 175ff. ISBN 0-201-63361-2.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help)