Tatars: Difference between revisions

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

The Volga Tatars used the Turkic [[Old Tatar language]] for their literature between the 15th and 19th centuries. It was written in the [[İske imlâ alphabet|İske imlâ]] variant of the [[Arabic script]], but actual spelling varied regionally. The older literary language included a large number of Arabic and Persian loanwords. The modern literary language, however, often uses Russian and other European-derived words instead. |

The Volga Tatars used the Turkic [[Old Tatar language]] for their literature between the 15th and 19th centuries. It was written in the [[İske imlâ alphabet|İske imlâ]] variant of the [[Arabic script]], but actual spelling varied regionally. The older literary language included a large number of Arabic and Persian loanwords. The modern literary language, however, often uses Russian and other European-derived words instead. |

||

Outside of Tatarstan, urban Tatars usually speak [[Russian language|Russian]] as their first language (in cities such as Moscow, [[Saint-Petersburg]], [[Nizhniy Novgorod]], [[Tashkent]], [[Almaty]], and cities of the [[Ural (region)|Ural]] and western Siberia) and other languages in a worldwide diaspora. |

|||

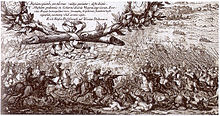

[[File:Firinat xalikov war.jpg|200px|thumb|right|[[Qolsharif]] and his students defend their mosque during the [[Siege of Kazan]].]] |

[[File:Firinat xalikov war.jpg|200px|thumb|right|[[Qolsharif]] and his students defend their mosque during the [[Siege of Kazan]].]] |

||

Revision as of 00:08, 24 January 2013

| Ruslan Chagaev • Dinara Safina Şihabetdin Märcani • Pyotr Gavrilov Gabdulkhay Akhatov • Sofia Gubaidulina • Diniyar Bilyaletdinov • Ğabdulla Tuqay | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| ca. 6.8 million[citation needed] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 5,310,649[1] |

| 467,829[2] | |

| 203,371[3] | |

| 73,304[4] | |

| 36,355[5] | |

| 31,500[citation needed] | |

| 19,000[citation needed] | |

| 5,000[citation needed] | |

| Languages | |

| Tatar, Russian | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam majority, Russian Orthodox minority | |

Tatars (Tatar: [Tatarlar / Татарлар] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), sometimes spelled Tartars) are a Turkic[6][7][8][9][10] ethnic group in Eastern Europe. The Tatars are native people of Volga region of Russia, Tatarstan and Bashkortostan. Most Tatars live in the Russian Federation, with a population of 5.5 million, including 2 million in the republic of Tatarstan, 1 million in the republic of Bashkortostan and 2.5 million in other regions of Russia. After the dissolution of the USSR, significant populations of Tatars found themselves in the newly independent Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Ukraine. However, there is a trend of repatriation of Tatars to Russia, including to Tatarstan and Bashkortostan.

History

The present territory of Tatarstan was inhabited by the Volga Bulgars who settled on the Volga river in the 7th century and converted to Islam in 922 during the missionary work of Ahmad ibn Fadlan.[citation needed] After the Mongol invasion, Bulgaria was defeated, ruined and incorporated in the Golden Horde. Much of the population survived, and there was a certain degree of mixing between it and the Kipchaks of the Horde during the ensuing period. The group as a whole accepted the exonym "Tatars" (finally in the end of the 19th century; although the name Bulgars persisted in some places; the majority identified themselves simply as the Muslims) and the language of the Kipchaks; on the other hand, the invaders eventually converted to Islam. As the Horde disintegrated in the 15th century, the area became the territory of the Kazan khanate, which was ultimately conquered by Russia in the 16th century.

Name

The name Tatar likely originated amongst the nomadic Tatar confederation in the north-eastern Gobi desert in the 5th century.[11] The name "Tatars" was used an alternative term for the Shiwei, a nomadic confederation to which these Tatar people belonged.

As various of these nomadic groups became part of Genghis Khan's army in the early 13th century, a fusion of Mongol and Turkic elements took place, and the invaders of Rus and the Pannonian Basin became known to Europeans as Tatars or Tartars (see Tatar yoke).[11] After the breakup of the Mongol Empire, the Tatars became especially identified with the western part of the empire, known as the Golden Horde.[11] "Tatar" was used by Christian Europeans to designate speakers of Altaic (Turkic, Mongolic, Tungusic) languages; for instance, Azeris were formerly called Iranian/Persian Tatars, and the Khakas were called Abakan Tatars. Later on however, the name "Tatar" was no longer used to refer to most Altaic-speakers: it became a name for the relatively unrelated Turkic-speaking Muslim populations of the former Golden Horde in Europe, such as those of the former Kazan, Crimean, Astrakhan, Qasim, and Siberian Khanates. The Muslim Nogays, Bashkirs, Azeris, Karachays, Balkars, Kumyks, and Kazakhs, as well as the Christian Chuvash were no longer designated as Tatars.

The form Tartar has its origins in either Latin or French, coming to Western European languages from Turkish and Persian Tātār ("mounted courier, mounted messenger; postrider"). From the beginning, the extra r was present in the Western forms, and according to the Oxford English Dictionary this was most likely due to an association with Tartarus (Hell in Greek mythology), though some claim that the name Tartar was in fact used amongst the Tatars themselves. Another possibility is that Tartar in British Received Pronunciation is pronounced as Tātar. Nowadays Tatar is usually used to refer to the people, but Tartar is still almost always used for derived terms such as tartar sauce or steak tartare.[12]

Some Volga Tatars prefer to be called Bulgars and reject the Tatar name, a position known as Bulgarism. Bulgarism pertains to the notion that the Volga Tatars are actual Bulgars.

Traditional celebrations

Historically, the traditional celebrations of Tatars depended largely on the agricultural cycle.

Spring/Summer period

Fall/Winter period

Tatar cuisine

Tatar cuisine is rich with authentic hot soups (şulpa), dough-based dishes (qistibi, pilmän, öçpoçmaq, etc.) and sweets (çäkçäk, göbädiä, etc.). Traditional Tatar beverages are ayran, katyk and kumys.

Subgroups

The majority of the Tatar population are Volga Tatars, native to the Volga region. Smaller notable subgroups include the Crimean Tatars, Lipka Tatars and Astrakhan Tatars in Europe and the Siberian Tatars in Asia.

Volga Tatars

Some Volga Tatars speak different dialects of Tatar language. Therefore, they form distinct groups such as the Mişär group and the Qasim group. Mişär-Tatars (or Mishars) are a group of Tatars speaking a dialect of the Tatar language. They live in Chelyabinsk, Tambov, Penza, Ryazan, Nizhegorodskaya oblasts of Russia and in Bashkortostan and Mordovia. They lived near and along the Volga River, in Tatarstan. The Western Tatars have their capital in the town of Qasím (Kasimov in Russian transcription) in Ryazan Oblast, with a Tatar population of 1100.[citation needed] A minority of Christianized Volga Tatars are known as Keräşens.

The Volga Tatars used the Turkic Old Tatar language for their literature between the 15th and 19th centuries. It was written in the İske imlâ variant of the Arabic script, but actual spelling varied regionally. The older literary language included a large number of Arabic and Persian loanwords. The modern literary language, however, often uses Russian and other European-derived words instead.

Outside of Tatarstan, urban Tatars usually speak Russian as their first language (in cities such as Moscow, Saint-Petersburg, Nizhniy Novgorod, Tashkent, Almaty, and cities of the Ural and western Siberia) and other languages in a worldwide diaspora.

In the 1910s the Volga Tatars numbered about half a million in the Kazan Governorate in Tatarstan, their historical homeland, about 400,000 in each of the governments of Ufa, 100,000 in Samara and Simbirsk, and about 30,000 in Vyatka, Saratov, Tambov, Penza, Nizhny Novgorod, Perm and Orenburg. An additional 15,000 had migrated to Ryazan or were settled as prisoners in the 16th and 17th centuries in Lithuania (Vilnius, Grodno and Podolia). An additional 2000 resided in St. Petersburg. The Kazan Tatars speak the Tatar language, a Turkic language with substantial amount of Russian and Arabic loanwords. Most Kazan Tatars practice Sunni Islam.

Before 1917, polygamy was practised[citation needed] only by the wealthier classes and was a waning institution.

There is an ethnic nationalist movement among Kazan Tatars which stresses descent from the Bulgars and is known as Bulgarism - there have been graffiti on the walls in the streets of Kazan with phrases such as "Bulgaria is alive".[citation needed]

A significant number of Volga Tatars emigrated during the Russian Civil War, mostly to Turkey and Harbin, China. According to the Chinese government, there are still 5,100 Tatars living in Xinjiang province.

Keräşens

Large numbers of Tatars were forcibly Christianized by Ivan the Terrible during the 16th century and later in the 18th century.

Some scientists suppose that Suars were ancestors of the Keräşen Tatars, and they had been converted to Christianity by Armenians in the 6th century, while they lived in the Caucasus. Suars, like other tribes (which later converted to Islam) became Volga Bulgars and later the modern Chuvash (mostly Christians) and Tatars (mostly Muslims).

Keräşen Tatars live all over Tatarstan and in Udmurtia, Bashkiria and Chelyabinsk Oblast. Some of them did assimilate among Chuvash and Tatars with Sunni Muslim self-identification. Eighty years of Atheistic Soviet rule made Tatars of both confessions not as religious as they were. As such, differences between Tatars and Keräşen Tatars now is only that Keräşens have Russian names.

Some Turkic (Kuman) tribes in Golden Horde converted to Christianity in the 13th and 14th centuries (Nestorianism). Some prayers, written in that time in the Codex Cumanicus, sound like modern Keräşen prayers, but there is no information about the connection between Christian Kumans and modern Keräşens.

Volga Tatars around the world

Places where Volga Tatars live include:

- Ural and Upper Kama (since the 15th century) 15th century - colonization, 16th - 17th century - re-settled by Russians, 17th - 19th century - exploring of Ural, working in the plants

- West Siberia (since the 16th century): 16th - from Russian repressions after conquering of Khanate of Kazan by Russians, 17th - 19th century - exploring of West Siberia, end of 19th - first half of the 20th century - industrialization, railways construction, 1930s - Joseph Stalin's repressions, 1970s - 1990s oil workers

- Moscow (since the 17th century): Tatar feudals in the service of Russia, tradesmen, since the 18th century - Saint-Petersburg

- Kazakhstan (since the 18th century): 18th – 19th centuries - Russian army officers and soldiers, 1930s – industrialization, since 1950s - settlers on virgin lands - re-emigration in 1990s

- Finland (since 1804): (mostly Mişärs) - 19th century - from a group of some 20 villages in the Sergach region on the Volga River. See Finnish Tatars.

- Central Asia (since the 19th century) (Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Xinjiang ) - 19th-century Russian officers and soldiers, tradesmen, religious emigrants, 1920-1930s - industrialization, Soviet education program for Central Asia peoples, 1948, 1960 - help for Ashgabat and Tashkent ruined by earthquakes - re-emigration in 1980s

- Caucasus, especially Azerbaijan (since the 19th century) - oil workers (1890s), bread tradesmen

- Northern China (since 1910s) - railway builders (1910s) - re-emigrated in 1950s

- East Siberia (since the 19th century) - resettled farmers (19th century), railroad builders (1910s, 1980s), exiled by the Soviet government in 1930s

- Germany and Austria - 1914, 1941 - prisoners of war, 1990s - emigration

- Turkey, Japan, Iran, China, Egypt (since 1918) - emigration

- UK, USA, Australia, Canada, Argentina, Mexico - (1920s) re-emigration from Germany, Turkey, Japan, China and others. 1950s - prisoners of war from Germany, which did not go back to the USSR, 1990s - emigration after the breakup of USSR

- Sakhalin, Kaliningrad, Belarus, Ukraine, Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania, Karelia - after 1944-45 builders, Soviet military personnel

- Murmansk Oblast, Khabarovsk Krai, Northern Poland and Northern Germany (1945–1990) - Soviet military personnel

- Israel - wives or husbands of Jews (1990s)

Astrakhan Tatars

The Astrakhan Tatars (around 80,000) are a group of Tatars, descendants of the Astrakhan Khanate's nomadic population, who live mostly in Astrakhan Oblast. For the 2000 Russian census 2000, most Astrakhan Tatars declared themselves simply as Tatars and few declared themselves as Astrakhan Tatars. A large number of Volga Tatars live in Astrakhan Oblast and differences between them have been disappearing.

The Astrakhan Tatars are further divided into the Kundrov, Yurt and Karagash Tatars. The latter are also at times called the Karashi Tatars.[13]

Text from Britannica 1911:

- The Astrakhan Tatars number about 10,000 and are, with the Kalmyks, all that now remains of the once so powerful Astrakhan empire. They also are agriculturists and gardeners; while some 12,000 Kundrovsk Tatars still continue the nomadic life of their ancestors.

While Astrakhan (Ästerxan) Tatar is a mixed dialect, around 43,000 have assimilated to the Middle (i.e., Kazan) dialect. Their ancestors are Khazars, Kipchaks and some Volga Bulgars. (Volga Bulgars had trade colonies in modern Astrakhan and Volgograd oblasts of Russia.)

The Astrakhan Tatars also assimilated the Agrzhan.[14]

Siberian Tatars

The Siberian Tatars occupy three distinct regions—a strip running west to east from Tobolsk to Tomsk—the Altay and its spurs—and South Yeniseisk. They originated in the agglomerations of various Uralo-Altaic stems that, in the region north of the Altay, reached some degree of culture between the 4th and 5th centuries, but were subdued and enslaved by the Mongols.

According to the 2002 census there are 400550 Tatars in Siberia, but 300,000 of them are Volga Tatars who settled in Siberia during periods of colonization.[15]

Baraba Tatars

The Baraba Tatars take their name from one of their stems (Barama). After a strenuous resistance to Russian conquest, and much suffering at a later period from Kyrgyz and Kalmyk raids, they now live by agriculture—either in separate villages or along with Russians.

They numbered at least 9000 in 1990.

Crimean Tatars

The Crimean Tatars emerged as a nation at the time of the Crimean Khanate. The Crimean Khanate was a Turkic-speaking Muslim state which was among the strongest powers in Eastern Europe until the beginning of the 18th century.[16] The rulers of the Crimean Tatars were the progeny of Hacı I Giray a Jochid descendant of Genghis Khan. The Crimean Tatars are subdivided into three sub-ethnic groups: the Tats (not to be confused with Tat people, living in the Caucasus region) who used to inhabit the mountainous Crimea before 1944 (about 55%), the Yalıboyu who lived on the southern coast of the peninsula (about 30%), and the Noğay (about 15%).

Lipka Tatars

The Lipka Tatars are a group of Turkic-speaking Tatars who originally settled in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania at the beginning of the 14th century. The first settlers tried to preserve their shamanistic religion and sought asylum amongst the non-Christian Lithuanians.[17] Towards the end of the 14th century, another wave of Tatars - this time, Muslims, were invited into the Grand Duchy by Vytautas the Great. These Tatars first settled in Lithuania proper around Vilnius, Trakai, Hrodna and Kaunas [17] and later spread to other parts of the Grand Duchy that later became part of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. These areas comprise present-day Lithuania, Belarus and Poland. From the very beginning of their settlement in Lithuania they were known as the Lipka Tatars.

Lithuanian Tatars

After Tokhtamysh the Khan of the Golden Horde and a direct Jochid descendant of Genghis Khan was defeated by Timur, some of his tribesmen and loyalists sought refuge in Grand Duchy of Lithuania. These Muslim Tatars were given land and nobility in return for military service and were known as Lipka Tatars. They are known to have taken part in the Battle of Grunwald.

Another group appeared in Jagoldai Duchy (Lithuania's vassal) near modern Kursk in 1437 and disappeared later.

The Lipka Tatars were among the first founders of Muslim communities in the United States.

Belarusian Tatars

Islam spread in Belarus from the 14th to the 16th century. The process was encouraged by the Lithuanian princes, who invited Tatar Muslims from the Crimea and the Golden Horde as guards of state borders. Already in the 14th century the Tatars had been offered a settled way of life, state posts and service positions. By the end of the 16th century over 100,000 Tatars settled in Belarus and Lithuania, including those hired to government service, those who moved there voluntarily, prisoners of war, etc.

Tatars in Belarus generally follow Sunni Hanafi Islam. Some groups have accepted Christianity and been assimilated, but most adhere to Muslim religious traditions, which ensures their definite endogamy and preservation of ethnic features. Interethnic marriages with representatives of Belarusian, Polish, Lithuanian, Russian nationalities are not rare, but do not result in total assimilation.

Originating from different ethnic associations, Belarusian (and also Polish and Lithuanian) Tatars back in ancient days lost their native language and adopted Belarusian, Polish and Russian. However, the liturgy is conducted in the Arabic language, which is known by the clergymen. There are an estimated 5,000-10,000 Tatars in Belarus.

Polish Tatars

- Main articles: Lipka Tatars and Islam in Poland

From the 13th to 17th centuries various groups of Tatars settled and/or found refuge within the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth. This was promoted especially by the Grand Dukes of Lithuania, because of their reputation as skilled warriors. The Tatar settlers were all granted with szlachta (nobility) status, a tradition that was preserved until the end of the Commonwealth in the 18th century. They included the Lipka Tatars (13th-14th centuries) as well as Crimean and Nogay Tatars (15th-16th centuries), all of which were noticeable in Polish military history, as well as Volga Tatars (16th-17th centuries). They all mostly settled in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, lands that are now in Lithuania and Belarus.

Various estimates of the number of Tatars in the Commonwealth in the 17th century are about 15,000 persons and 60 villages with mosques. Numerous royal privileges, as well as internal autonomy granted by the monarchs allowed the Tatars to preserve their religion, traditions and culture over the centuries. The Tatars were allowed to intermarry with Christians, a thing uncommon in Europe at the time. The May Constitution of 1791 gave the Tatars representation in the Polish Sejm.

Although by the 18th century the Tatars adopted the local language, the Islamic religion and many Tatar traditions (e.g. the sacrifice of bulls in their mosques during the main religious festivals) were preserved. This led to formation of a distinctive Muslim culture, in which the elements of Muslim orthodoxy mixed with religious tolerance formed a relatively liberal society. For instance, the women in Lipka Tatar society traditionally had the same rights and status as men, and could attend non-segregated schools.

About 5,500 Tatars lived within the inter-war boundaries of Poland (1920–1939), and a Tatar cavalry unit had fought for the country's independence. The Tatars had preserved their cultural identity and sustained a number of Tatar organisations, including a Tatar archives, and a museum in Wilno (Vilnius).

The Tatars suffered serious losses during World War II and furthermore, after the border change in 1945 a large part of them found themselves in the Soviet Union. It is estimated that about 3000 Tatars live in present-day Poland, of which about 500 declared Tatar (rather than Polish) nationality in the 2002 census. There are two Tatar villages (Bohoniki and Kruszyniany) in the north-east of present-day Poland, as well as urban Tatar communities in Warsaw, Gdańsk, Białystok, and Gorzów Wielkopolski. Tatars in Poland sometimes have a Muslim surname with a Polish ending: Ryzwanowicz; another surname sometimes adopted by more assimilated Tatars is Taterczyński, literally "son of a Tatar".

The Tatars were relatively very noticeable in the Commonwealth military as well as in Polish and Lithuanian political and intellectual life for such a small community.[citation needed] In modern-day Poland, their presence is also widely known, due in part to their noticeable role in the historical novels of Henryk Sienkiewicz, which are universally recognized in Poland. A number of Polish intellectual figures have also been Tatars, e.g. the prominent historian Jerzy Łojek.

A small community of Polish speaking Tatars settled in Brooklyn, New York City in the early 1900s. They established a mosque that is still in use today.

Dobruja Tatars

- Main articles: Tatars of Romania, Crimean Tatars in Romania and Crimean Tatars in Bulgaria

Tatars were present on the territory of today's Romania and Bulgaria since the 13th century. In Romania, according to the 2002 census, 24,000 people declared their ethnicity as Tatar, most of them being Crimean Tatars living in Constanţa County in the region of Dobruja. The Crimean Tatars were colonized there by the Ottoman Empire beginning in the 17th century.

Tatar language

The Tatar language together with the Bashkir language forms the Kypchak-Bolgar (also "Uralo-Caspian") group within the Kypchak languages (Northwestern Turkic).

There are three Tatar dialects: Eastern, Central, Western.[18] The Western dialect (Misher) is spoken mostly by Mishärs, the Central dialect is spoken by Kazan and Astrakhan Tatars, and the Eastern (Sibir) dialect is spoken by Siberian Tatars in western Siberia. All three dialects have subdialects. Central Tatar is the base of literary Tatar.

Tatar was written with the Arabic alphabet prior to 1928, in the so-called İske imlâ alphabet and from 1920 to 1928 in the Yaña imlâ alphabet. In 1928 the Soviet Union introduced a Latin orthography, known as Jaŋalif. Jaŋalif was replaced by a Cyrillic orthography in 1940. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, use of Jaŋalif was revived, but the Cyrillic script was again enforced in 2002, when the Russian Federation passed a controversial law enforcing the use of Cyrillic for all official languages.[19]

Famous Tatars

- Gabdulkhay Akhatov, scientist, linguist.

- Marat Kabaev, footbaler and coach

- Aliya Garayeva, rhythmic gymnast

- Ğabdulla Tuqay, classic of the Tatar literature, a critic and a publisher.

- Hadi Taqtaş, Soviet Tatar poet, writer and publicist.

- Ğäliäsğar Kamal, Tatar writer, dramatist and playwright. Galiaskar Kamal Tatar Academic Theatre is named after him.

- Ayaz İshaki, eading figure of the Tatar national movement, author, journalist, publisher and politician.

- Sadri Maksudi Arsal, prominent Tatar and Turkish statesman, scholar and thinker.

- Yusuf Akçura, prominent Tatar activist and ideologue of Turanism in the late Ottoman Empire.

- Musa Cälil, he is the only poet of the Soviet Union who was simultaneously awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union award for his resistance fighting, and the Lenin Prize for authoring The Moabit Notebooks; both the awards were awarded to him posthumously.

- Sara Sadíqova, actress, singer (soprano), and composer.

- Marat Safin, tennis player and politician.

- Aliya Mustafina, artistic gymnast.

- Irina Shayk, Russian model (was born to ethnic Tatar father and Russian mother).

Gallery

Tatar Artists

Tatar Businessmen

Tatar Poets

Tatar Athletes

See also

References

- ^ Russian Census 2010: Population by ethnicity Template:Ru icon

- ^ "Uzbekistan - Ethnic minorities" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-06-03.

- ^ Агентство Республики Казахстан по статистике: Численность населения Республики Казахстан по отдельным этносам на 1 января 2012 года

- ^ "About number and composition population of Ukraine by data All-Ukrainian census of the population 2001". Ukraine Census 2001. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ^ Asgabat.net-городской социально-информационный портал :Итоги всеобщей переписи населения Туркменистана по национальному составу в 1995 году.

- ^ Encyclopedia Brittanica: Tatar, also spelled Tartar, any member of several Turkic-speaking peoples ... [1]

- ^ The Columbia Encyclopedia: Tatars (tä´tərz) or Tartars (tär´tərz), Turkic-speaking peoples living primarily in Russia, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan. [2]

- ^ Meriam-Webster: Tatar - a member of any of a group of Turkic peoples found mainly in the Tatar Republic of Russia and parts of Siberia and central Asia [3]

- ^ Oxford Dictionaries: Tatar - a member of a Turkic people living in Tatarstan and various other parts of Russia and Ukraine. They are the descendants of the Tartars who ruled central Asia in the 14th century. [4]

- ^ Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East and North Africa: Turks are an ethnolinguistic group living in a broad geographic expanse extending from southeastern Europe through Anatolia and the Caucasus Mountains and throughout Central Asia. Thus Turks include the Turks of Turkey, the Azeris of Azerbaijan, and the Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Tatars, Turkmen, and Uzbeks of Central Asia, as well as many smaller groups in Asia speaking Turkic languages. [5]

- ^ a b c Tatar. (2006). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved October 28, 2006, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://search.eb.com/eb/article-9071375

- ^ "Tartar, Tatar, n.2 (a.)". (1989). In Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 11 September 2008, from Oxford English Dictionary Online.

- ^ Olson, James S., An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1994) p. 55

- ^ Wixman, Ronald. The Peoples of the USSR: An Ethnographic Handbook. (Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe, Inc, 1984) p. 15

- ^ Siberian Tatars

- ^ Halil İnalcik, 1942 [page needed]

- ^ a b Template:Lt icon Lietuvos totoriai ir jų šventoji knyga - Koranas

- ^ Akhatov G. "Tatar dialectology". Kazan, 1984.(Tatar language)

- ^ Russia reconsiders Cyrillic law BBC News, 5 October 2004.