Nubians: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

In ancient times Nubians were depicted by [[Egyptians]] as having very dark skin, often shown with hooped [[earrings]] and with braided or extended hair.<ref>[http://www.dignubia.org/maps/timeline/img/b1540a-nubian-tribute-huy.jpg Dig Nubia] – Image</ref> Ancient Nubians were famous for their skill and precision with the bow.<ref>[http://www.dignubia.org/maps/timeline/bce-3200.htm Dig Nubia] – Nubia: Land of the Bow</ref> They were hired by the Carthaginian general Hannibal in the Punic Wars to fight against the Romans for their horsemanship. |

In ancient times Nubians were depicted by [[Egyptians]] as having very dark skin, often shown with hooped [[earrings]] and with braided or extended hair.<ref>[http://www.dignubia.org/maps/timeline/img/b1540a-nubian-tribute-huy.jpg Dig Nubia] – Image</ref> Ancient Nubians were famous for their skill and precision with the bow.<ref>[http://www.dignubia.org/maps/timeline/bce-3200.htm Dig Nubia] – Nubia: Land of the Bow</ref> They were hired by the Carthaginian general Hannibal in the Punic Wars to fight against the Romans for their horsemanship. |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

Revision as of 08:59, 1 January 2013

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Languages | |

| Kenuzi-Dongola, Nobiin, other Nubian languages; Sudanese Arabic, Egyptian Arabic, Sa'idi Arabic, | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam |

The Nubians (Template:Lang-ar/Template:Lang-ar) are an ethnic group originally from northern Sudan, and southern Egypt. The Nubian people in Sudan inhabit the region between Wadi Halfa in the north and Aldaba in the south. The main Nubian groups from north to south are the Halfaweyen, Sikut, Mahas, and Danagla. They speak different dialects of the Nubian language.

In ancient times Nubians were depicted by Egyptians as having very dark skin, often shown with hooped earrings and with braided or extended hair.[1] Ancient Nubians were famous for their skill and precision with the bow.[2] They were hired by the Carthaginian general Hannibal in the Punic Wars to fight against the Romans for their horsemanship.

History

Nubians are the people of southern Egypt and northern Sudan, settling along the banks of the Nile from Aswan. They were very famous for their horsemanship, for which they rode their horses bareback and held on by their knees, making them light, mobile, and efficient, and a good cavalry choice. Their Nubian language is an Eastern Sudanic language, part of the Nilo-Saharan phylum.

The Old Nubian language is attested from the 8th century, and is thus the oldest recorded language of Africa outside of the Afro-Asiatic group. It was the language of the Noba nomads who occupied the Nile between the First and Third Cataracts and the Makorae nomads who occupied the land between the Third and Fourth Cataracts following the collapse of the Kingdom of Kush sometime in the 4th century CE. The Makorae were a separate tribe who eventually conquered or inherited the lands of the Noba: they established a Byzantine-influenced state called the Kingdom of Makuria which administered the Noba lands separately as the eparchy of Nobadia. Nobadia was converted to Miaphysitism by the Orthodox priest Julian and Bishop Longinus of Constantinople, and thereafter received its bishops from the Pope of Alexandria.

The name "Nubia" or "Nubian" has a contested origin. It may originate with an ancient Egyptian noun, nebu, meaning gold. Another etymology claims that it originates with the name of a particular group of people, the Noubai, living in the area that would become known as Nubia. Scholars may also refer to Nubians as Kushites, a reference to the Kush, the territory of the Nubians as it was called by Ancient Egyptians.[3] It may originate with the Greek historian Strabo, who referred to the Nubas people.[4]

The earliest history of ancient Nubia comes from the Paleolithic Era of 300,000 years ago. By around 6000 BCE, the Nubians had developed an agricultural economy and had contact with Egypt. The Nubians began using a system of writing relatively late in their history, when they adopted the Egyptian system. Ancient Nubian history is categorized according to the following periods:[5]

- A-group culture (3700-2800 BCE)

- C-group culture (2300-1600 BCE)

- Kingdom of Kerma (2500-1500 BCE)

- Nubian contemporaries of Egyptian New Kingdom (1550-1069 BCE)

- Kingdom of Napata and Egypt's Nubian dynasty XXV (1000-653 BCE)

- Kingdom of Napata (1000-275 BCE)

- Kingdom of Meroe (275 BCE-300/350 CE)

Nubia consisted of four regions with varied agriculture and landscapes. The Nile river and its valley lay in the north and central parts of Nubia, allowing farming using irrigation. The western Sudan had a mixture of peasant agriculture and nomadism. Eastern Sudan had primarily nomadism, with a few areas of irrigation and agriculture. Finally, there was the fertile pastoral region of the south, where Nubia's larger agricultural communities were located.[6]

Nubia was dominated by kings from clans that controlled the gold mines. Trade in exotic goods from other parts of Africa—ivory, animal skins—passed to Egypt through Nubia.

Modern Nubians

The descendants of the ancient Nubians still inhabit the general area of what was ancient Nubia. Today, they live in what is called the former Old Nubia, which is mainly in modern Egypt. Nubians have been resettled in large numbers (an estimated 50,000 people) away from southern Egypt since the 1960s, when the Aswan High Dam was built on the Nile, flooding ancestral lands.[7] Some resettled Nubians continue working as farmers (sharecroppers) on resettlement farms whose landowners live elsewhere; most work in Egypt's cities. Whereas Arabic was once only learned by Nubian men who travelled for work, it is increasingly being learned by Nubian women who have access to school, radio and television. Nubian women are working outside the home in increasing numbers.[8]

Culture

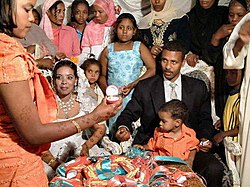

Nubian Egyptians have had a strong interest in the archeological discoveries of recent decades that have brought a richer knowledge of ancient Nubia. Nubians were often subjected to discrimination in Egypt before this research became widely known. Nubians now take pride in their cultural history. Some express an affinity with Sudanese culture, as many have relatives in Sudan. This common identity has been celebrated in poetry, novels, music and storytelling.[9]

Nubians in modern Sudan include the Danaqla around Dongola Reach, the Mahas from the Third Cataract to Wadi Halfa, and the Sikurta around Aswan. These Nubians write using their own script. They also practice scarification: Mahas men and women have three scars on each cheek, while the Danaqla wear these scars on their temples. Younger generations appear to be abandoning this custom.[10]

Nubia's ancient cultural development was influenced by its geography. It is sometimes divided into Upper Nubia and Lower Nubia. Upper Nubia was where the ancient Kingdom of Napata (the Kush) was located. Lower Nubia has been called "the corridor to Africa", where there was contact and cultural exchange between Nubians, Egyptians, Greeks, Assyrians, Romans, and Arabs. Lower Nubia was also where the Kingdom of Meroe flourished.[11] The languages spoken by modern Nubians are based on ancient Sudanic dialects. From north to south, they are: Kenuz, Fadicha (Matoki), Sukkot, Mahas, Danagla.[12]

Kerma, Nepata and Meroe were Nubia's largest population centres. The rich agricultural lands of Nubia supported these cities. Ancient Egyptian rulers sought control of Nubia's wealth, including gold and the important trade routes within its territories.[13] Nubia's trade links with Egypt led to Egypt's domination over Nubia during the New Kingdom period. Egypt's language, writing system, and architecture were imposed on Nubia. The emergence of the Kingdom of Meroe in the 8th century BCE led to Egypt being under the control of Nubian rulers for half a century, although they preserved many Egyptian cultural traditions.[14] Nubian kings were considered pious scholars and patrons of the arts, copying ancient Egyptian texts and even restoring some Egyptian cultural practices.[15] After this, Egypt's influence declined greatly. Meroe became the centre of power for Nubia and cultural links with sub-Saharan Africa gained greater influence.[16]

Religion

Today, Nubians practise Islam. To a degree, Nubian religious practices involve a syncretism of Islam and traditional folk beliefs.[17] In ancient times, Nubians practised a mixture of traditional religion and Egyptian religion. Before the spread of Islam, many Nubians were adherents of Christianity.[18]

Ancient Nepata was an important religious centre in Nubia. It was the locaton of Gebel Barkal, a massive sandstone hill resembling a rearing cobra in the eyes of the ancient inhabitants. Egyptian priests declared it to be the home of the ancient deity Amun, further enhancing Nepata as an ancient religious site. This was the case for both Egyptians and Nubians. Egyptian and Nubian deities alike were worshipped in Nubia for 2500 years, even while Nubia was under the control of the New Kingdom of Egypt.[19] Nubian kings and queens were buried near Gebel Barkal, in pyramids as the Egyptian pharaohs were. Nubian pyramids were built at Gebel Barkal, at Nuri (across the Nile from Gebel Barkal), at El Kerru, and at Merroe, south of Gebel Barkal.[20]

Architecture

Modern Nubian architecture in Sudan is distinctive, and typically features a large courtyard surrounded by a high wall. A large, ornately decorated gate, preferably facing the Nile, dominates the property. Brightly coloured stucco is often decorated with symbols connected with the family inside, or popular motifs such as geometric patterns, palm trees, or the evil eye that wards away bad luck.[21]

Nubians invented the Nubian vault a type of curved surface forming a vaulted structure.[citation needed]

Prominent Nubians

- Alara of Nubia, founder of the Twenty-fifth dynasty of Egypt

- Taharqa, Pharaoh of the Twenty-fifth dynasty

- Anwar Sadat, Late third President of Egypt ( Egyptian Nubian father, Sudanese Nubian mother)

- Gaafar Nimeiry, Former Sudanese president

- Mohammed Wardi, Singer

- Mohamed Mounir, Singer

- Ali Hassan Kuban, Singer and musician

- Hamza El Din, Singer and musicologist

- Khalil Kalfat, Literary critic, political and economic thinker and writer

- Abdallah Khalil, Ex-Sudanese Prime Minister, co-founder of the White Flag League, co-Founder and ex-general secretary of the Umma Party

- Mohamed Hussein Tantawi Soliman, Egyptian Field Marshal and statesman, commander-in-chief of the Egyptian Armed Forces, de facto head of state of Egypt

- Jamal Muhammad Ahmed, Sudanese diplomat, statesmen, author, poet

- Ibrahim Ahmad, Prominent Sudanese politician, first Sudanese head of the University of Khartoum, first Secretary of Treasury, the first chairman of the Bank of Sudan, co-founder of Umma party, Author and negotiator of the Sudanese Declaration of Independence

- Abdul-Rahman al Mahdi, Grandson of the mahdi, prominent Sudanese dtatesman

- Muhammad Ahmad, 19th century Sufi sheikh and self-proclaimed mahdi

- Jamal Abu Seif, Founder of Itihad, the first politically-active group in the Sudan and predecessor of the famous White Flag League

- Sheikh Khalil Ateeg, Founder of the Day'fiya Ismailiya Sufi tariqa in the Sudan

- Abdu Dahab Hassanein, Founder of the Sudanese Communist Party

- Dawwod Abdul-Latif, First mayor of Khartoum

- Mohammed Tawfeg, ex-Minister of Exterior, ex-Minister of the Media

- Mo Ibrahim, Sudanese-born British mobile communications entrepreneur, one of the richest men in the United Kingdom

- Idris Ali, Egyptian novelist and short story writer

- Ibrahim Awad, Late Sudanese Musician .

- Osama Abdul Latif, Sudanese businessman, Chairman of DAL group

- Shikabala, Mahmoud Abdel Razek Fadlallah, Egyptian footballer who currently plays for Egyptian Premier League club Zamalek SC,

References

- ^ Dig Nubia – Image

- ^ Dig Nubia – Nubia: Land of the Bow

- ^ Bianchi, Robert Steven (2004). Daily Life Of The Nubians. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 2, 5. ISBN 9780313325014.

- ^ Remier, Pat (2010). Egyptian Mythology, A to Z. Infobase Publishing. p. 135. ISBN 9781438131801.

- ^ Bianchi, Robert Steven (2004). Daily Life Of The Nubians. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 2–3. ISBN 9780313325014.

- ^ Lobban, Richard (2004). Historical Dictionary of Ancient and Medieval Nubia. Scarecrow Press. pp. liii. ISBN 9780810847842.

- ^ Fernea, Robert A. (2005). Nubian Ceremonial Life: Studies in Islamic Syncretism And Cultural Change. American University in Cairo Press. pp. ix–xi. ISBN 9789774249556.

- ^ Fernea, Robert A. (2005). Nubian Ceremonial Life: Studies in Islamic Syncretism And Cultural Change. American University in Cairo Press. pp. ix–xi. ISBN 9789774249556.

- ^ Kemp, Graham, and Douglas P. Fry (2003). Keeping the Peace: Conflict Resolution and Peaceful Societies Around the World. Psychology Press. p. 99. ISBN 9780415947626.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Clammer, Paul (2010). Sudan: the Bradt travel guide. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 138. ISBN 9781841622064.

- ^ Lobban, Richard (2004). Historical Dictionary of Ancient and Medieval Nubia. Scarecrow Press. pp. liii. ISBN 9780810847842.

- ^ Lobban, Richard (2004). Historical Dictionary of Ancient and Medieval Nubia. Scarecrow Press. pp. liv. ISBN 9780810847842.

- ^ Bulliet, Richard W., and Pamela Kyle Crossley, Daniel R. Headrick, Lyman L. Johnson, Steven W. Hirsch (2007). The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History to 1550. Cengage Learning. p. 82. ISBN 9780618771509.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bulliet, Richard W., and Pamela Kyle Crossley, Daniel R. Headrick, Lyman L. Johnson, Steven W. Hirsch (2007). The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History to 1550. Cengage Learning. p. 83. ISBN 9780618771509.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Remier, Pat (2010). Egyptian Mythology, A to Z. Infobase Publishing. p. 135. ISBN 9781438131801.

- ^ Bulliet, Richard W., and Pamela Kyle Crossley, Daniel R. Headrick, Lyman L. Johnson, Steven W. Hirsch (2007). The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History to 1550. Cengage Learning. p. 83. ISBN 9780618771509.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fernea, Robert A. (2005). Nubian Ceremonial Life: Studies in Islamic Syncretism And Cultural Change. American University in Cairo Press. pp. iv–ix. ISBN 9789774249556.

- ^ Clammer, Paul (2010). Sudan: the Bradt travel guide. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 138. ISBN 9781841622064.

- ^ Remier, Pat (2010). Egyptian Mythology, A to Z. Infobase Publishing. p. 135. ISBN 9781438131801.

- ^ Remier, Pat (2010). Egyptian Mythology, A to Z. Infobase Publishing. p. 135. ISBN 9781438131801.

- ^ Clammer, Paul (2010). Sudan: the Bradt travel guide. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 138. ISBN 9781841622064.

- Rouchdy, Aleya (1991). Nubians and the Nubian Language in Contemporary Egypt: A Case of Cultural and Linguistic Contact. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-09197-1.

- Valbelle, Dominique (2007). The Nubian Pharaohs: Black Kings on the Nile. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 977-416-010-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Warnock Fernea, Elizabeth (1990). Nubian Ethnographies. Chicago: Waveland Press Inc. ISBN 0-88133-480-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Black Pharaohs - National Geographic Feb 2008