History of liberalism: Difference between revisions

clarification |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

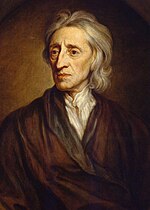

'''Liberalism''' is the belief in freedom and equal rights generally associated with such thinkers as [[John Locke]] and [[Montesquieu]]. Liberalism as a political movement spans the better part of the last four centuries, though the use of the word ''liberalism'' to refer to a specific political doctrine did not occur until the 19th century. Perhaps the first modern state founded on liberal principles, with no hereditary aristocracy, was [[ |

'''Liberalism''' is the belief in freedom and equal rights generally associated with such thinkers as [[John Locke]] and [[Montesquieu]]. Liberalism as a political movement spans the better part of the last four centuries, though the use of the word ''liberalism'' to refer to a specific political doctrine did not occur until the 19th century. Perhaps the first modern state founded on liberal principles, with no hereditary aristocracy, was the [[United States of America]], whose [[Declaration of Independence]] states that "all men are created equal and endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights". A few years later, the [[French Revolution]] overthrew the hereditary aristocracy, with the slogan "liberty, equality, fraternity", and was the first state in history to grant [[universal male suffrage]].The [[Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen]], first codified in 1789 in [[France]], is a foundational document of both liberalism and [[human rights]]. |

||

Some argue that |

Some argue that Liberalism started as a major doctrine and political endeavor in response to the religious wars gripping Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries. Some scholars also point to historical precedents of modern liberalism in the writings of the [[School of Salamanca]], [[Thomas Aquinas]], the [[Stoics]] and [[Aristotle]].<ref>If the newly burgeoning liberal Thomism began with Cardinal Cajeta in Italy, the torch was soon passed to a set of sixteeth century theologians who revived Thomism and scholasticism and kept them alive for over a century: the School of Salamaca in Spain. - Murray N. Rothbard, Economic Thought Before Adam Smith, Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2006. (p. 101)</ref><ref>Both Rothbard and Hayek have argued that the roots of the Austrian School came from the teachings of the School of Salamanca in the 15th century and Physiocrats in the 18th century. - http://archive.mises.org/10900/the-second-full-day-in-salamanca/</ref><ref>Jerry M. Williams, Robert E. Lewis, Early Images of the Americas: Transfer and Invention, University of Arizona Press, 1993</ref><ref>J. Budziszewski, True Tolerance: Liberalism and the Necessity of Judgment, Transaction Publishers, 1999. (p. 127)</ref><ref>J. Budziszewski, The nearest coast of darkness: a vindication of the politics of virtues, Cornell University Press, 1988.</ref><ref>Ernest Gellner, Cesar Cansino, Liberalism in Modern Times: Essays in Honour of Jose G. Merquior, Central European University Press, 1996</ref> In any case, the intellectual progress of the [[Age of Enlightenment|Enlightenment]], which questioned old traditions about societies and governments, eventually coalesced into powerful revolutionary movements that toppled archaic regimes all over the world, especially in [[Liberalism in Europe|Europe]], [[Liberalism and conservatism in Latin America|Latin America]], and [[Liberalism in the United States|North America]]. Liberalism fully exploded as a comprehensive movement against the [[Ancien Régime|old order]] during the [[French Revolution]], which set the pace for the future development of human history. |

||

[[Classical liberalism|Classical liberals]], who broadly emphasized the importance of [[free market]]s and [[civil liberties]], dominated liberal history in the 19th century. The onset of the [[First World War]] and the [[Great Depression]], however, accelerated the trends begun in late 19th century Europe toward [[social liberalism]] that emphasized a greater role for the state in ameliorating devastating social conditions. By the beginning of the 21st century, [[liberal democracy|liberal democracies]] and their fundamental characteristics—support for [[constitution]]s, [[Election|free and fair elections]] and [[Pluralism (political philosophy)|pluralistic society]]—had prevailed in most regions around the world. |

[[Classical liberalism|Classical liberals]], who broadly emphasized the importance of [[free market]]s and [[civil liberties]], dominated liberal history in the 19th century. The onset of the [[First World War]] and the [[Great Depression]], however, accelerated the trends begun in late 19th century Europe toward [[social liberalism]] that emphasized a greater role for the state in ameliorating devastating social conditions. By the beginning of the 21st century, [[liberal democracy|liberal democracies]] and their fundamental characteristics—support for [[constitution]]s, [[Election|free and fair elections]] and [[Pluralism (political philosophy)|pluralistic society]]—had prevailed in most regions around the world. |

||

Revision as of 16:41, 15 October 2012

Liberalism is the belief in freedom and equal rights generally associated with such thinkers as John Locke and Montesquieu. Liberalism as a political movement spans the better part of the last four centuries, though the use of the word liberalism to refer to a specific political doctrine did not occur until the 19th century. Perhaps the first modern state founded on liberal principles, with no hereditary aristocracy, was the United States of America, whose Declaration of Independence states that "all men are created equal and endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights". A few years later, the French Revolution overthrew the hereditary aristocracy, with the slogan "liberty, equality, fraternity", and was the first state in history to grant universal male suffrage.The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, first codified in 1789 in France, is a foundational document of both liberalism and human rights.

Some argue that Liberalism started as a major doctrine and political endeavor in response to the religious wars gripping Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries. Some scholars also point to historical precedents of modern liberalism in the writings of the School of Salamanca, Thomas Aquinas, the Stoics and Aristotle.[1][2][3][4][5][6] In any case, the intellectual progress of the Enlightenment, which questioned old traditions about societies and governments, eventually coalesced into powerful revolutionary movements that toppled archaic regimes all over the world, especially in Europe, Latin America, and North America. Liberalism fully exploded as a comprehensive movement against the old order during the French Revolution, which set the pace for the future development of human history.

Classical liberals, who broadly emphasized the importance of free markets and civil liberties, dominated liberal history in the 19th century. The onset of the First World War and the Great Depression, however, accelerated the trends begun in late 19th century Europe toward social liberalism that emphasized a greater role for the state in ameliorating devastating social conditions. By the beginning of the 21st century, liberal democracies and their fundamental characteristics—support for constitutions, free and fair elections and pluralistic society—had prevailed in most regions around the world.

Prelude

After centuries of dominance, the Roman Empire irrevocably splintered in 476. The eastern part of the Roman world became the Byzantine Empire and the western part fractured into a series of kingdoms that collectively represented a shadow of the erstwhile Roman eagle. Despite these enormous geopolitical changes, however, one constant remained to give Europe a certain sense of unity and stability: Christianity. Originally insulted as a fringe cult, Christians were persecuted for centuries after the death of Jesus, but they spread efficiently throughout the empire despite constant harassment from Roman authorities, appealing especially to the poor and those at the bottom of the social ladder.[7] When Constantine integrated Christians into Roman life in the 4th century, the stage was set for the eventual domination of the Christian religion. Although the Roman Empire collapsed and splintered, Christianity was sufficiently entrenched into the fabric of society to survive the resulting sociopolitical chaos that characterized the period.[8]

Christianity provided the post-Roman European world with a sense of purpose and direction. European experiences during the Middle Ages were often characterized by fear, uncertainty, and warfare—the latter being especially endemic in medieval life.[9] Christian societies largely believed that history unfolded according to a divine plan over which humans had little control.[10] Something of a quid pro quo relationship emerged between the Catholic Church and regional rulers: the Church gave kings and queens authority to rule while the latter spread the message of the Christian faith and did the bidding of Christian social and military forces.[11] It was an astute, symbiotic relationship in a world rife with uncertainty and danger. For much of the Middle Ages, the authority of the Church was virtually unquestioned and unquestionable. Leaders who challenged that authority were often severely rebuked and sometimes even publicly embarrassed, as evidenced by Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV waiting barefoot in the snow at the fort of Canossa to receive forgiveness from the Pope.[12] The world was very pious and religion permeated all aspects of life. The influence of the Church can be seen by the fact that the very term often referred to European society as a whole.[13] When it invoked the will of God in 1095, the Church set the stage for dozens of crusades against pagans, Muslims, and various other groups.

The Church experienced fortunate times that lasted for centuries, but outside events and internal struggles crippled the power of the greatest institution in European life. In the 14th century, disputes over papal successions—and, indeed, over just who was the Pope and who was not—rocked the Western world.[14] These disputes significantly harmed the reputation of the Church. The middle of the 14th century also witnessed the spread of the Black Death, which exterminated perhaps up to one-third of the European population—some 20 million humans gone in just a few years.[15] These enormous fatality rates incensed people across the continent, and much of their rage was directed at the Church, which was viewed as ineffectual in the face of such carnage.[16] The Black Death had a profound influence on future European history, laying the groundwork—through peasant uprisings and the eventual emergence of a small class of property owners—for the eventual pluralism that became a hallmark of the liberal world.[17]

The emergence of the Renaissance in the 15th century also helped to weaken unquestioning submission to the Church by reinvigorating interest in science and in the classical world.[18] In the 16th century, the Protestant Reformation developed from sentiments that viewed the Church as an oppressive ruling order too involved in the feudal and baronial structure of European society.[19] In response to the Protestant Reformation, the Church launched a Counter Reformation to contain the bubbling sentiments, but this effort ultimately unraveled in the Thirty Years War, a deadly European conflict that lasted from 1618 until 1648. The war saw Catholic forces suffer massive defeats, and the religious unity of Europe was shattered. [citation needed]

In England, disputes between the Parliament and King Charles I sparked a massive civil war in the 1640s. Charles was executed in 1649 and the Parliament ultimately succeeded—with the so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688—in establishing a limited and constitutional monarchy after decades of strife.

Beginning

A pivotal figure in the development of liberal philosophy as a distinct ideology was the English philosopher John Locke[20][21]. Arguments between Locke and Thomas Hobbes inspired later social contract theories outlining the relationship between people and their governments.[22] Locke developed the relatively radical notion that government acquires consent from the governed. His influential Two Treatises (1690), the foundational text of liberal ideology, outlined his major ideas. Once humans moved out of their natural state and formed societies, Locke argued as follows: "Thus that which begins and actually constitutes any political society is nothing but the consent of any number of freemen capable of a majority to unite and incorporate into such a society. And this is that, and that only, which did or could give beginning to any lawful government in the world."[23] The stringent insistence that lawful government did not have a supernatural basis was a sharp break with the dominant theories of governance, which advocated the divine right of kings,[24] and echoed the earlier thought of Aristotle. One political scientist described this new thinking as follows: "In the liberal understanding, there are no citizens within the regime who can claim to rule by natural or supernatural right, without the consent of the governed".[25]

Locke had other intellectual opponents besides Hobbes. In the First Treatise, Locke aimed his guns first and foremost at one of the doyens of 17th century English conservative philosophy: Robert Filmer. Filmer's Patriarcha (1680) argued for the Divine Right of Kings by appealing to biblical teaching, claiming that the authority granted to Adam by God gave successors of Adam in the male line of descent a right of dominion over all other humans and creatures in the world.[26] Locke disagreed so thoroughly and obsessively with Filmer, however, that the First Treatise is almost a sentence-by-sentence refutation of Patriarcha. Reinforcing his respect for consensus, Locke argued that "conjugal society is made up by a voluntary compact between men and women".[27] Locke maintained that the grant of dominion in Genesis was not to men over women, as Filmer believed, but to humans over animals.[28] Locke was certainly no feminist by modern standards, but the first major liberal thinker in history accomplished an equally major task on the road to making the world more pluralistic: the integration of women into social theory.[29]

The journey of liberalism continued beyond Locke. French philosopher René Descartes asked in the 17th century if there were any beliefs that one could hold a priori. He concluded that self-existence—"I think, therefore I am"—and the existence of a supernatural deity were two such beliefs.[30] Descartes was looking for absolute certainty because of his deep skepticism about received knowledge. Once Descartes introduced systematic doubt as a formal philosophy, the intelligentsia of the European world took up the banner and spearheaded the Enlightenment, a period of profound intellectual vitality that questioned old traditions and influenced several European monarchies throughout the 18th century. A prominent example of a monarch who took the Enlightenment project seriously was Joseph II of Austria, who ruled from 1780 to 1790 and implemented a wide array of radical reforms, such as the complete abolition of serfdom, the imposition of equal taxation policies between the aristocracy and the peasantry, the institution of religious toleration, including equal civil rights for Jews, and the suppression of Catholic religious authority throughout his empire, creating a more secular nation.[31] Besides the Enlightenment, a rising tide of industrialization and urbanization in Western Europe during the 18th century also contributed to the growth of liberal society by spurring commercial and entrepreneurial activity. The ideas and trends developing at the time did not exist in a vacuum, a fact to which the Americans and later the French, with permanent consequences for human history, paid much tribute.[citation needed]

Era of revolution

The American colonies had been loyal British subjects for decades, but tensions between the two sides were exacerbated by the Seven Years War, which lasted from 1756 until 1763. The war drained British coffers and forced the monarchy to squeeze more and more resources from its recalcitrant colonies. The colonies resented this taxation without representation and decided, after a myriad of internal discussions and petitions to the British government, that they would declare independence and face the consequences. The Declaration of Independence, written by Thomas Jefferson, echoed Locke convincingly: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, and are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness".[32] Military engagements in the American Revolution began in 1775 and were largely complete by 1781, when a Franco-American army combined with a French fleet bottled up thousands of British troops at Yorktown. The American Revolution formally concluded in 1783 with the Treaty of Paris, in which the British recognized American independence.

After the war, the colonies debated about how to move forward. Their first attempt at cooperation transpired under the Articles of Confederation, which were eventually regarded as too inadequate to provide security, or even a functional government. The colonies held a Constitutional Convention in 1787 to resolve the problems stemming from the Articles of Confederation. The resulting Constitution of the United States was a monumental document in American history and in world history as well. In the context of the times, the Constitution was an extremely revolutionary and liberal document.[citation needed] The Americans skipped the monarchical system and settled on a republic, laying the groundwork for over two centuries of liberal democratic expansion throughout the globe.[citation needed] The Constitution revealed the degree to which the Enlightenment had influenced the American colonies.[citation needed] The basic fabric of the new American government was lifted from the pages of a French philosopher, the Baron de Montesquieu, whose Spirit of Laws (1748) laid the framework for a republic with three branches of government: the executive, the legislative, and the judicial.[33] The American theorists and politicians who created the Constitution were also heavily influenced by the ideas of Locke. As one historian writes: "The American adoption of a democratic theory that all governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed, as it had been put as early as the Declaration of Independence, was epoch-marking".[34] The American Revolution was an important struggle in liberal history, and it was quickly followed by the most important: the French Revolution.

Three years into the French Revolution, German writer Johann von Goethe reportedly told the defeated Prussian soldiers after the Battle of Valmy that "from this place and from this time forth commences a new era in world history, and you can all say that you were present at its birth".[35] Historians widely regard the Revolution as one of the most important events in human history, and the end of the early modern period is attributed to the onset of the Revolution in 1789.[36] The Revolution is often seen as marking the "dawn of the modern era,"[37] and its convulsions are widely associated with "the triumph of liberalism".[38] Describing the participatory politics of the French Revolution, one historian commented that "thousands of men and even many women gained firsthand experience in the political arena: they talked, read, and listened in new ways; they voted; they joined new organizations; and they marched for their political goals. Revolution became a tradition, and republicanism an enduring option".[39] For liberals, the Revolution was their defining moment, and later liberals approved of the French Revolution almost entirely—"not only its results but the act itself," as two historians noted.[40]

The French Revolution began in 1789 with the convocation of the Estates-General in May. The first year of the Revolution witnessed members of the Third Estate proclaiming the Tennis Court Oath in June, the Storming of the Bastille in July, the passage of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in August, and an epic march on Versailles that forced the royal court back to Paris in October. The next few years were dominated by tensions between various liberal assemblies and a conservative monarchy intent on thwarting major reforms. A republic was proclaimed in September 1792 and King Louis XVI was executed the following year. External events also played a dominant role in the development of the Revolution. The French Revolutionary Wars started in 1792 and ultimately led to spectacular French victories: the conquest of the Italian peninsula, the Low Countries, and most territories west of the Rhine—achievements that had eluded previous French governments for centuries. Internally, popular sentiments radicalized the Revolution, culminating in the brutal Reign of Terror from 1793 until 1794. After the fall of Robespierre and the Jacobins, the Directory assumed control of the French state in 1795 and held power until 1799, when it was replaced by the Consulate under Napoleon Bonaparte.[citation needed]

Napoleon ruled as First Consul for about five years, centralizing power and streamlining the bureaucracy along the way. The Napoleonic Wars, pitting the heirs of a revolutionary state against the old monarchies of Europe, started in 1805 and lasted for a decade. Along with their boots and Charleville muskets, French soldiers brought to the rest of the European continent the liquidation of the feudal system, the liberalization of property laws, the end of seigneurial dues, the abolition of guilds, the legalization of divorce, the disintegration of Jewish ghettos, the collapse of the Inquisition, the permanent destruction of the Holy Roman Empire, the elimination of church courts and religious authority, the establishment of the metric system, and equality under the law for all men.[41] Napoleon wrote that "the peoples of Germany, as of France, Italy and Spain, want equality and liberal ideas,"[42] with some historians suggesting that he may have been the first person ever to use the word liberal in a political sense.[43] He also governed through a method that one historian described as "civilian dictatorship," which "drew its legitimacy from direct consultation with the people, in the form of a plebiscite".[44] Napoleon did not always live up the liberal ideals he espoused, however. His most lasting achievement, the Civil Code, served as "an object of emulation all over the globe,"[45] but it also perpetuated further discrimination against women under the banner of the "natural order".[46]

Stubborn French ambitions combined with a long conflict against Britain, the failure of the Continental System, and the catastrophe in Russia eventually led to the collapse of the First Empire in 1815 at the fields of Waterloo, where the Imperial Guard made its last stand under the rhythms of the Marseillaise, which was banned in the Bourbon Restoration.[47] Klemens von Metternich, the Austrian foreign minister, constructed the basis for the conservative decades that stretched into the middle of the 19th century.[citation needed] This unprecedented period of chaos and revolution, however, had introduced the world to a new movement and ideology that would soon crisscross the globe.

Children of revolution

The world after the French Revolution provided liberals with an opportunity to reshape the basic structures of society. Abolitionist and suffrage movements took off in the 19th century throughout the Western world. Slowly but surely, democratic ideals were spreading. Parliamentary power in Britain increased, France established an enduring republic in the 1870s, and a vicious war in the United States ensured the survival of that nation and signaled the end of slavery. Meanwhile, strange assortments of liberal and nationalist sentiments were on the march in Italy and Germany, which finally coalesced into nations in the late 19th century. Liberal agitation in Latin America reached a fever pitch as the region was gradually brought into the common social and political patterns of the modern world.[citation needed]

Liberals after the Revolution wanted to develop a world free from government intervention, or at least free from too much government intervention. They championed the ideal of negative liberty, which constitutes the absence of coercion and the absence of external constraints.[48] They believed governments were cumbersome burdens and they wanted governments to stay out of the lives of individuals.[49] Liberals simultaneously pushed for the expansion of civil rights and for the expansion of free markets and free trade as part of the Industrial Revolution. The latter kind of economic thinking had been formalized by Adam Smith in his monumental Wealth of Nations (1776), an important marker in the history of capitalism. Smith revolutionized the field of economics and posited the existence of an "invisible hand" of the free market as a self-regulating mechanism that did not depend on external interference.[50] Sheltered by liberalism, the laissez-faire economic world of the 19th century emerged with full tenacity, particularly in the United States and in the United Kingdom.[51]

Politically, liberals saw the 19th century as a gateway to achieving the promises of 1789. In Spain, the Liberales, the first group to use the liberal label in a political context,[52] fought for the implementation of the 1812 Constitution for decades—overthrowing the monarchy in 1820 as part of the Trienio Liberal and defeating the conservative Carlists in the 1830s. In France, the July Revolution of 1830, orchestrated by liberal politicians and journalists, removed the Bourbon monarchy and inspired similar uprisings elsewhere in Europe. Frustration with the pace of political progress, however, sparked even more gigantic revolutions in 1848. Revolutions spread throughout the Austrian Empire, the German states, and the Italian states. Governments fell rapidly. Liberal nationalists demanded written constitutions, representative assemblies, greater suffrage rights, and freedom of the press.[53] A second republic was proclaimed in France. Serfdom was abolished in Prussia, Galicia, Bohemia, and Hungary.[54] The supposedly indomitable Metternich, the Austrian builder of the reigning conservative order, shocked Europe when he resigned and fled to Britain in panic and disguise.[55] Eventually, however, the success of the revolutionaries petered out. Without French help, the Italians were easily defeated by the Austrians. With some luck and skill, Austria also managed to contain the bubbling nationalist sentiments in Germany and Hungary, helped along by the failure of the Frankfurt Assembly to unify the German states into a single nation. Under abler leadership, however, the Italians and the Germans wound up realizing their dreams for independence. The Sardinian Prime Minister, Camillo di Cavour, was a shrewd liberal who understood that the only effective way for the Italians to gain independence was if the French were on their side.[56] Napoleon III agreed to Cavour's request for assistance and France defeated Austria in the Franco-Austrian War of 1859, setting the stage for Italian independence. German unification transpired under the leadership of Otto von Bismarck, who decimated the enemies of Prussia in war after war, finally triumphing against France in 1871 and proclaiming the German Empire in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, ending another saga in the drive for nationalization. The French proclaimed a third republic after their loss in the war, and the rest of French history transpired under republican eyes.[citation needed]

Just a few decades after the French Revolution, liberalism went global. The liberal and conservative struggles in Spain also replicated themselves in Latin America. Like its former master, the region was a hotbed of wars, conflicts, and revolutionary activity throughout the 19th century. In Mexico, the liberales instituted the program of La Reforma in the 1850s, reducing the power of the military and the Catholic Church.[57] The conservadores were outraged at these steps and launched a revolt, which sparked a deadly conflict. From 1857 to 1861, Mexico was gripped in the bloody War of Reform, a massive internal and ideological confrontation between the liberals and the conservatives.[58] The liberals eventually triumphed and Benito Juárez, a dedicated liberal and now a Mexican national hero, became the president of the republic. After Juárez, Mexico suffered from prolonged periods of dictatorial repression, which lasted until the Mexican Revolution in the early 20th century. Another regional example of liberal influence can be found in Ecuador. As with other nations throughout the region at the time, Ecuador was steeped in conflict and uncertainty after gaining independence from Spain. By the middle of the 19th century, the country had descended into chaos and madness, with the people divided between rival liberal and conservative camps. From these conflicts, García Moreno established a conservative government that ruled the country for several years. The liberals, however, were incensed at the conservative regime and overthrew it completely in the Liberal Revolution of 1895. The Radical Liberals who toppled the conservatives were led by Eloy Alfaro, a firebrand who implemented a variety of sociopolitical reforms, including the separation of church and state, the legalization of divorce, and the establishment of public schools.[59]

Liberals were active throughout the world in the 19th century, but it was in Britain that the future character of liberalism would take shape. The liberal sentiments unleashed after the revolutionary era of the previous century ultimately coalesced into the Liberal Party, formed in 1859 from various Radical and Whig elements. The Liberals produced one of the greatest British prime ministers—William Gladstone, who was also known as the Grand Old Man.[60] Under Gladstone, the Liberals reformed education, disestablished the Church of Ireland, and introduced the secret ballot for local and parliamentary elections. Following Gladstone, and after a period of Conservative domination, the Liberals returned with full strength in the general election of 1906, aided by working class voters worried about food prices. After that historic victory, the Liberal Party shifted from its classical liberalism and laid the groundwork for the future British welfare state, establishing various forms of health insurance, unemployment insurance, and pensions for elderly workers.[61] The intellectual foundations for this new liberalism were coherently established by philosopher Thomas Hill Green, who conceived of positive liberty as the freedom of the individual to achieve his or her potential.[62] After various global and catastrophic events, including wars and economic collapses, this new kind of liberalism would sweep over much of the world in the 20th century.[citation needed]

Wars and renewal

The 20th century started perilously for liberalism. The First World War sparked geopolitical turmoil throughout the European continent and threatened to unravel the success of liberal democracy. However, the Allies managed to win and the number of republics in Europe reached 13 by the end of the war, as compared with only three at the start of the war in 1914.[63] The Russian Revolution, which occurred during the war, marked another milestone on the road of modernity. The eventual communist victory and the creation of the Soviet Union highlighted the threat that liberalism now faced from a new and dangerous enemy. Meanwhile, the uncertain world that emerged from the cauldron of the First World War suffered from massive economic setbacks in the years following 1918. Inflation skyrocketed in many European nations and the stock market in the United States collapsed in 1929, triggering a series of recessions throughout the Western world that became collectively known as the Great Depression. Liberalism survived, winning out against fascism in the Second World War before facing off against communism for several more decades during the Cold War.[citation needed]

World War I proved a major challenge for liberal democracies, although they ultimately defeated the dictatorial states of the Central Powers. The war precipitated the collapse of older forms of government, including empires and dynastic states, a phenomenon that became quite apparent in Russia. The massive defeats that Russia sustained in the first few years of World War I significantly tainted the reputation of the monarchy, already reeling from earlier losses to Japan and political struggles with the Kadets, a powerful liberal bloc in the Duma. Facing huge shortages in basic necessities along with widespread riots in early 1917, Czar Nicholas II abdicated in March, bringing to an end three centuries of Romanov rule and paving the way for liberals to declare a republic. To Russia's liberals, the French Revolution was the centerpiece of human history, and they repeatedly used the slogans, symbols, and ideas of the Revolution—plastering liberté, égalité, fraternité over major public spaces—to establish an emotional attachment to the past, an attachment that liberals hoped would galvanize the public to fight for modern values.[64] But democracy was no simple task, and the Provisional Government that took over the country's administration needed the cooperation of the Petrograd Soviet, an organization that united leftist industrial laborers, to function and survive. Under the uncertain leadership of Alexander Kerensky, however, the Provisional Government mismanaged Russia's continuing involvement in the war, prompting angry reactions from the Petrograd workers, who drifted further and further to the left. The Bolsheviks, a communist group led by Vladimir Lenin, seized the political opportunity from this confusion and launched a second revolution in Russia during the same year. The communists violently overthrew the fragile liberal-socialist order in October, after which Russia witnessed several years of civil war between communists and conservatives wishing to restore the monarchy. The communist challenge to liberalism, however, paled in comparison to the economic problems that rocked the Western world in the 1930s.[citation needed]

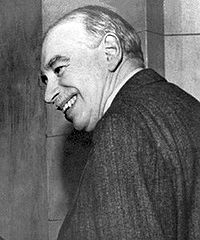

The Great Depression fundamentally changed the liberal world. It was such a calamitous period in Western civilization that the civilization itself appeared on the verge of complete collapse. There was an inkling of a new liberalism during the First World War, and even earlier in the 19th century among some states and regions, but modern liberalism finally hatched in the 1930s with the Great Depression and a new economic mastermind whose ideas formalized the responsibilities of the modern state in its administration of the economy: John Maynard Keynes. Classical liberals posited that completely free markets were the optimal economic units capable of effectively allocating resources—that over time, in other words, they would produce full employment and economic security.[65] Keynes spearheaded a broad assault on classical economics and its followers, arguing that totally free markets were not ideal, and that hard economic times required intervention and investment from the state. Where the market failed to properly allocate resources, for example, the government was required to stimulate the economy until private funds could start flowing again—a "prime the pump" kind of strategy designed to boost industrial production.[66]

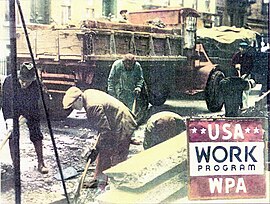

The social liberal program launched by President Roosevelt in the United States, the New Deal, proved very popular with the American public. In 1933, when FDR came into office, the unemployment rate stood at roughly 25 percent.[67] The size of the economy, measured by the gross national product, had fallen to half the value it had in early 1929.[68] The electoral victories of FDR and the Democrats precipitated a deluge of deficit spending and public works programs. In 1940, the level of unemployment had fallen by 10 points to around 15 percent.[69] Additional state spending and the gigantic public works program sparked by the Second World War eventually pulled the United States out of the Great Depression. From 1940 to 1941, government spending increased by 59 percent, the gross domestic product skyrocketed 17 percent, and unemployment fell below 10 percent for the first time since 1929.[70] By 1945, after vast government spending, public debt stood at a staggering 120 percent of GNP, but unemployment had been effectively eliminated.[71] Most nations that emerged from the Great Depression did so with deficit spending and strong intervention from the state.[citation needed]

The economic woes of the period prompted widespread unrest in the European political world, leading to the rise of fascism as an ideology and a movement arrayed against both liberalism and communism. Broadly speaking, fascist ideology emphasized elite rule and absolute leadership, a radical rejection of equality, the imposition of patriarchal society, a stern commitment to war as an instrument of natural behavior, the elimination of supposedly inferior or subhuman groups from the structure of the nation, and the conception of life as an "unending struggle" in which the strong would destroy and dominate the weak.[72] In Germany, the Nazis slighted the first year of the French Revolution: "1789 is abolished".[73] Echoing the Germans, Mussolini stated that "we stand for a new principle in the world; we stand for the sheer, categorical, definitive antithesis to the world of democracy...to the world which still abides by the fundamental principles laid down in 1789".[74] Hitler went further, commenting "The main plank in the National Socialist program is to abolish the liberal concept of the individual and the Marxist concept of humanity, and to substitute for them the Volk community, rooted in the soil and united by the bond of its common blood".[75] The fascist and nationalist grievances of the 1930s eventually culminated in the Second World War, the deadliest conflict in human history. The Allies prevailed in the war by 1945, and their victory set the stage for the Cold War between communist states and liberal democracies.[citation needed]

The Cold War featured extensive ideological competition and several proxy wars, but the widely feared Third World War between the Soviet Union and the United States never occurred. While communist states and liberal democracies competed against one another, an economic crisis in the 1970s inspired a temporary move away from Keynesian economics across many Western governments. This classical liberal renewal, known as neoliberalism, lasted through the 1980s and the 1990s, although recent economic troubles have prompted a resurgence in Keynesian economic thought. Meanwhile, nearing the end of the 20th century, communist states in Eastern Europe collapsed precipitously, leaving liberal democracies as the only major forms of government in the West. At the beginning of the Second World War, the number of democracies around the world was about the same as it had been forty years before.[76] After 1945, liberal democracies spread very quickly. Even as late as 1974, roughly 75 percent of all nations were considered dictatorial, but now more than half of all countries are democracies.[77] Liberalism faces recurring challenges, however, including conservatism and religious fundamentalism in several regions throughout the world. The rise of China is also challenging Western liberalism with a combination of authoritarian government and economic reforms that preceded democratization.[78]

Notes

- ^ If the newly burgeoning liberal Thomism began with Cardinal Cajeta in Italy, the torch was soon passed to a set of sixteeth century theologians who revived Thomism and scholasticism and kept them alive for over a century: the School of Salamaca in Spain. - Murray N. Rothbard, Economic Thought Before Adam Smith, Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2006. (p. 101)

- ^ Both Rothbard and Hayek have argued that the roots of the Austrian School came from the teachings of the School of Salamanca in the 15th century and Physiocrats in the 18th century. - http://archive.mises.org/10900/the-second-full-day-in-salamanca/

- ^ Jerry M. Williams, Robert E. Lewis, Early Images of the Americas: Transfer and Invention, University of Arizona Press, 1993

- ^ J. Budziszewski, True Tolerance: Liberalism and the Necessity of Judgment, Transaction Publishers, 1999. (p. 127)

- ^ J. Budziszewski, The nearest coast of darkness: a vindication of the politics of virtues, Cornell University Press, 1988.

- ^ Ernest Gellner, Cesar Cansino, Liberalism in Modern Times: Essays in Honour of Jose G. Merquior, Central European University Press, 1996

- ^ Colton and Palmer, p. 15. The Christian teaching spread at first among the poor, the people at the bottom of society, those whom Greek glories and Roman splendors had passed over or enslaved, and who had the least to delight in or to hope for in the existing world.

- ^ Tanner, p. xviii.

- ^ Tanner, p. xx.

- ^ Olson, p. 183.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, pp. 22–4.

- ^ Roberts, p. 476. To avoid trial before the German bishops presided over by Gregory (who was already on his way to Germany), Henry came in humiliation to Canossa, where he waited in the snow barefoot until Gregory would receive his penance in one of the most dramatic of all confrontations of lay and spiritual authority.

- ^ Roberts, p. 473. By 'the Church' as an earthly institution, Christians mean the whole body of the faithful, lay and cleric alike. In this sense the Church came to be the same thing as European society during the Middle Ages.

- ^ Tanner, p. 1.

- ^ Tanner, p. xix.

- ^ Peters, p. 47.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, pp. 47–8.

- ^ Johnson, p. 28. Dante was not just a mediaval man, he was a Renaissance man too. He was highly critical of the church, like many scholars who followed him.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, p. 75. They might wish to manage their own religious affairs as they did their other business, believing that the church hierarchy was too much embedded in a feudal, baronial, and monarchical system with which they had little in common.

- ^ Delaney, p. 18.

- ^ Godwin et al., p. 12.

- ^ Copleston, pp. 39–41.

- ^ Locke, p. 170.

- ^ Forster, p. 219.

- ^ Zvesper, p. 93.

- ^ Copleston, p. 33.

- ^ Kerber, p. 189.

- ^ Kerber, p. 189.

- ^ Kerber, p. 189.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, p. 291.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, p. 333.

- ^ Bernstein, p. 48.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, p. 320.

- ^ Roberts, p. 701.

- ^ Coker, p. 3.

- ^ Frey, Foreword.

- ^ Frey, Preface.

- ^ Ros, p. 11.

- ^ Hanson, p. 189.

- ^ Manent and Seigel, p. 80.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, pp. 428–9.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, p. 428.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, p. 428.

- ^ Lyons, p. 111.

- ^ Lyons, p. 94.

- ^ Lyons, pp. 98–102.

- ^ Lyons, p. 139.

- ^ Heywood, p. 47.

- ^ Heywood, pp. 47–8.

- ^ Heywood, p. 52.

- ^ Heywood, p. 53.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, p. 479.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, p. 510.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, p. 510.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, p. 509.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, pp. 546–7.

- ^ Stacy, p. 698.

- ^ Stacy, p. 698.

- ^ Handelsman, p. 10.

- ^ Cook, p. 31.

- ^ Heywood, p. 61.

- ^ Heywood, p. 59.

- ^ Mazower, p. 3.

- ^ Shlapentokh, pp. 220–8.

- ^ Shaw, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Colton and Palmer, p. 808.

- ^ Auerbach and Kotlikoff, p. 299.

- ^ Dobson, p. 264.

- ^ Steindl, p. 111.

- ^ Knoop, p. 151.

- ^ Rivlin, p. 53.

- ^ Heywood, pp. 218–26.

- ^ Heywood, p. 214.

- ^ Perry et al., p. 759.

- ^ Perry et al., p. 759.

- ^ Colomer, p. 62.

- ^ Diamond, cover flap.

- ^ Peerenboom, pp. 7–8.

References and further reading

- Adams, Ian. Ideology and politics in Britain today. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-7190-5056-1

- Alterman, Eric. Why We're Liberals. New York: Viking Adult, 2008. ISBN 0-670-01860-0

- Ameringer, Charles. Political parties of the Americas, 1980s to 1990s. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1992. ISBN 0-313-27418-5

- Antoninus, Marcus Aurelius. The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN 0-19-954059-4

- Arnold, N. Scott. Imposing values: an essay on liberalism and regulation. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. ISBN 0-495-50112-3

- Auerbach, Alan and Kotlikoff, Laurence. Macroeconomics Cambridge: MIT Press, 1998. ISBN 0-262-01170-0

- Bernstein, Richard. Thomas Jefferson: The Revolution of Ideas. New York: Oxford University Press US, 2004. ISBN 0-19-514368-X

- Browning, Gary et al. Understanding Contemporary Society: Theories of the Present. Thousand Oaks: SAGE, 2000. ISBN 0-7619-5926-2

- Chodos, Robert et al. The unmaking of Canada: the hidden theme in Canadian history since 1945. Halifax: James Lorimer & Company, 1991. ISBN 1-55028-337-5

- Coker, Christopher. Twilight of the West. Boulder: Westview Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8133-3368-7

- Colomer, Josep Maria. Great Empires, Small Nations. New York: Routledge, 2007. ISBN 0-415-43775-X

- Colton, Joel and Palmer, R.R. A History of the Modern World. New York: McGraw Hill, Inc., 1995. ISBN 0-07-040826-2

- Cook, Richard. The Grand Old Man. Whitefish: Kessinger Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-4191-6449-X

- Copleston, Frederick. A History of Philosophy: Volume V. New York: Doubleday, 1959. ISBN 0-385-47042-8

- Delaney, Tim. The march of unreason: science, democracy, and the new fundamentalism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-19-280485-5

- Diamond, Larry. The Spirit of Democracy. New York: Macmillan, 2008. ISBN 0-8050-7869-X

- Dobson, John. Bulls, Bears, Boom, and Bust. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2006. ISBN 1-85109-553-5

- Dore, Elizabeth and Molyneux, Maxine. Hidden histories of gender and the state in Latin America. Duke University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-8223-2469-5

- Dorrien, Gary. The making of American liberal theology. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001. ISBN 0-664-22354-0

- Farr, Thomas. World of Faith and Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press US, 2008. ISBN 0-19-517995-1

- Falco, Maria. Feminist interpretations of Mary Wollstonecraft. State College: Penn State Press, 1996. ISBN 0-271-01493-8

- Flamm, Michael and Steigerwald, David. Debating the 1960s: liberal, conservative, and radical perspectives. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2008. ISBN 0-7425-2212-1

- Forster, Greg. John Locke's politics of moral consensus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-521-84218-2

- Frey, Linda and Frey, Marsha. The French Revolution. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2004. ISBN 0-313-32193-0

- Gallagher, Michael et al. Representative government in modern Europe. New York: McGraw Hill, 2001. ISBN 0-07-232267-5

- Gifford, Rob. China Road: A Journey into the Future of a Rising Power. Random House, 2008. ISBN 0-8129-7524-3

- Godwin, Kenneth et al. School choice tradeoffs: liberty, equity, and diversity. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002. ISBN 0-292-72842-5

- Gould, Andrew. Origins of liberal dominance. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1999. ISBN 0-472-11015-2

- Gray, John. Liberalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995. ISBN 0-8166-2801-7

- Gregg, Pauline. Free-Born John: A Biography of John Lilburne. Phoenix Press, 2001. ISBN 978-1-84212-200-6

- Grigsby, Ellen. Analyzing Politics: An Introduction to Political Science. Florence: Cengage Learning, 2008. ISBN 0-495-50112-3

- Gross, Jonathan. Byron: the erotic liberal. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2001. ISBN 0-7425-1162-6

- Hafner, Danica and Ramet, Sabrina. Democratic transition in Slovenia: value transformation, education, and media. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2006. ISBN 1-58544-525-8

- Handelsman, Michael. Culture and Customs of Ecuador. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2000. ISBN 0-313-30244-8

- Hanson, Paul. Contesting the French Revolution. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing, 2009. ISBN 1-4051-6083-7

- Hartz, Louis. The liberal tradition in America. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1955. ISBN 0-15-651269-6

- Heywood, Andrew. Political Ideologies: An Introduction. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. ISBN 0-333-96177-3

- Hodge, Carl. Encyclopedia of the Age of Imperialism, 1800–1944. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008. ISBN 0-313-33406-4

- Jensen, Pamela Grande. Finding a new feminism: rethinking the woman question for liberal democracy. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 1996. ISBN 0-8476-8189-0

- Johnson, Paul. The Renaissance: A Short History. New York: Modern Library, 2002. ISBN 0-8129-6619-8

- Karatnycky, Adrian. Freedom in the World. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 2000. ISBN 0-7658-0760-2

- Karatnycky, Adrian et al. Nations in transit, 2001. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 2001. ISBN 0-7658-0897-8

- Kerber, Linda. "The Republican Mother". Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976.

- Kirchner, Emil. Liberal parties in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-521-32394-0

- Knoop, Todd. Recessions and Depressions Westport: Greenwood Press, 2004. ISBN 0-313-38163-1

- Lightfoot, Simon. Europeanizing social democracy?: the rise of the Party of European Socialists. New York: Routledge, 2005. ISBN 0-415-34803-X

- Locke, John. Two Treatises of Government. reprint, New York: Hafner Publishing Company, Inc., 1947. ISBN 0-02-848500-9

- Locke, John. A Letter Concerning Toleration: Humbly Submitted. CreateSpace, 2009. ISBN 978-1-4495-2376-3

- Lyons, Martyn. Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution. New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc., 1994. ISBN 0-312-12123-7

- Mackenzie, G. Calvin and Weisbrot, Robert. The liberal hour: Washington and the politics of change in the 1960s. New York: Penguin Group, 2008. ISBN 1-59420-170-6

- Manent, Pierre and Seigel, Jerrold. An Intellectual History of Liberalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-691-02911-3

- Mazower, Mark. Dark Continent. New York: Vintage Books, 1998. ISBN 0-679-75704-X

- Mernissi, Fatima. Islam and Democracy: Fear of the Modern World. Basic Books, 2002. ISBN 0-7382-0745-4

- Monsma, Stephen and Soper, J. Christopher. The Challenge of Pluralism: Church and State in Five Democracies. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2008. ISBN 0-7425-5417-1

- Olson, Roger. The mosaic of Christian belief: twenty centuries of unity and diversity. Westmont: InterVarsity Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8308-2695-5

- Peerenboom, Randall. China modernizes. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 0-19-920834-4

- Penniman, Howard. Canada at the polls, 1984: a study of the federal general elections. Durham: Duke University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-8223-0821-5

- Perry, Marvin et al. Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics, and Society. Florence, KY: Cengage Learning, 2008. ISBN 0-547-14742-2

- Peters, Stephanie. The Black Death. New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 2004. ISBN 0-7614-1633-1

- Pierson, Paul. The New Politics of the Welfare State. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-19-829756-4

- Puddington, Arch. Freedom in the World: The Annual Survey of Political Rights and Civil Liberties. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007. ISBN 0-7425-5897-5

- Riff, Michael. Dictionary of modern political ideologies. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990. ISBN 0-7190-3289-X

- Rivlin, Alice. Reviving the American Dream Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 1992. ISBN 0-8157-7476-1

- Roberts, J.M. The Penguin History of the World. New York: Penguin Group, 1992. ISBN 0-19-521043-3

- Ros, Agustin. Profits for all?: the cost and benefits of employee ownership. New York: Nova Publishers, 2001. ISBN 1-59033-061-7

- Routledge, Paul et al. The geopolitics reader. New York: Routledge, 2006. ISBN 0-415-34148-5

- Ryan, Alan. The Making of Modern Liberalism (Princeton UP, 2012)

- Schell, Jonathan. The Unconquerable World: Power, Nonviolence, and the Will of the People. New York: Macmillan, 2004. ISBN 0-8050-4457-4

- Shaw, G. K. Keynesian Economics: The Permanent Revolution. Aldershot, England: Edward Elgar Publishing Company, 1988. ISBN 1-85278-099-1

- Shlapentokh, Dmitry. The French Revolution and the Russian Anti-Democratic Tradition. Edison, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1997. ISBN 1-56000-244-1

- Sinclair, Timothy. Global governance: critical concepts in political science. Oxford: Taylor & Francis, 2004. ISBN 0-415-27662-4

- Song, Robert. Christianity and Liberal Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-19-826933-1

- Stacy, Lee. Mexico and the United States. New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 2002. ISBN 0-7614-7402-1

- Steinberg, David I. Burma: the State of Myanmar. Georgetown University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-87840-893-2

- Steindl, Frank. Understanding Economic Recovery in the 1930s. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2004. ISBN 0-472-11348-8

- Susser, Bernard. Political ideology in the modern world. Upper Saddle River: Allyn and Bacon, 1995. ISBN 0-02-418442-X

- Tanner, Norman. The Church in the Later Middle Ages. New York: I.B. Tauris, 2008. ISBN 1-84511-438-8

- Van den Berghe, Pierre. The Liberal dilemma in South Africa. Oxford: Taylor & Francis, 1979. ISBN 0-7099-0136-4

- Van Schie, P. G. C. and Voermann, Gerrit. The dividing line between success and failure: a comparison of Liberalism in the Netherlands and Germany in the 19th and 20th Centuries. Berlin: LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster, 2006. ISBN 3-8258-7668-3

- Various authors. Countries of the World & Their Leaders Yearbook 08, Volume 2. Detroit: Thomson Gale, 2007. ISBN 0-7876-8108-3

- Venturelli, Shalini. Liberalizing the European media: politics, regulation, and the public sphere. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-19-823379-5

- Wempe, Ben. T. H. Green's theory of positive freedom: from metaphysics to political theory. Exeter: Imprint Academic, 2004. ISBN 0-907845-58-4

- Wolfe, Alan. The Future of Liberalism. New York: Random House, Inc., 2009. ISBN 0-307-38625-2

- Worell, Judith. Encyclopedia of women and gender, Volume I. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2001. ISBN 0-12-227246-3

- Young, Shaun. Beyond Rawls: an analysis of the concept of political liberalism. Lanham: University Press of America, 2002. ISBN 0-7618-2240-2

- Zvesper, John. Nature and liberty. New York: Routledge, 1993. ISBN 0-415-08923-9