Sojourner Truth: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 75.190.163.170 (talk) to last version by Denisarona |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

| birth_date = Isabella Baumfree<br/>c. 1797 |

| birth_date = Isabella Baumfree<br/>c. 1797 |

||

| death_date = {{death date|1883|11|26|mf=y}} (aged 86) |

| death_date = {{death date|1883|11|26|mf=y}} (aged 86) |

||

| birth_place = [[Swartekill, New York]] |

| birth_place = [[Swartekill, New York]]. Hump me in the butt. |

||

| death_place = [[Battle Creek]], [[Michigan]] |

| death_place = [[Battle Creek]], [[Michigan]] |

||

| occupation = [[domestic servant]], [[abolitionist]], [[author]] |

| occupation = [[domestic servant]], [[abolitionist]], [[author]] |

||

Revision as of 13:31, 23 April 2012

Sojourner Truth | |

|---|---|

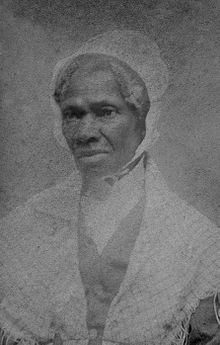

An albumen silver print from approximately 1870 by Randall Studios | |

| Born | Isabella Baumfree c. 1797 Swartekill, New York. Hump me in the butt. |

| Died | November 26, 1883 (aged 86) |

| Occupation(s) | domestic servant, abolitionist, author |

| Parent(s) | James and Elizabeth Baumfree |

Sojourner Truth (/[invalid input: 'icon']soʊˈdʒɜːrnər ˈtruːθ/; c. 1797 – November 26, 1883) was the self-given name, from 1843 onward, of Isabella Baumfree, an African-American abolitionist and women's rights activist. Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, Ulster County, New York, but escaped with her infant daughter to freedom in 1826. After going to court to recover her son, she became the first black woman to win such a case against a white man. Her best-known extemporaneous speech on racial inequalities, Ain't I a Woman?, was delivered in 1851 at the Ohio Women's Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. During the Civil War, Truth helped recruit black troops for the Union Army; after the war, Truth tried unsuccessfully to secure land grants from the federal government for former slaves.

Early years

Truth was one of "ten or twelve" children born to James and Elizabeth Baumfree.[1] James Baumfree was a slave captured from the Gold Coast in modern-day Ghana. Elizabeth Baumfree, also known as Mau-Mau Bet to children who knew her, was the daughter of African slaves from the Coast of Guinea.[2] The Baumfree family were slaves of Colonel Hardenbergh. The Hardenbergh estate was in a hilly area called by the Dutch name Swartekill (just north of present-day Rifton), in the town of Esopus, New York, 95 miles north of New York City.[3] After the colonel's death, ownership of the family slaves passed to his son, Charles Hardenbergh.[4]

After the death of Charles Hardenbergh in 1806, Truth, known as Belle, was sold at an auction. She was about 9 years old and was included with a flock of sheep for $100 to John Neely, near Kingston, New York. Until she was sold, Truth spoke only Dutch.[5] She suffered many hardships at the hands of Neely, whom she later described as cruel and harsh and who once beat her with a bundle of rods. Truth previously said Neely beat her daily. Neely sold her in 1808, for $105, to Martinus Schryver of Port Ewen, a tavern keeper, who owned her for 18 months. Schryver sold her in 1810, for $175, to John Dumont of West Park, New York.[6] Although this fourth owner was kindly disposed toward her, his wife found numerous ways to harass Truth and make her life more difficult.[4]

Around 1815, Truth met and fell in love with a slave named Robert from a neighboring farm. Robert's owner (Catlin) forbade the relationship; he did not want his slave to have children with a slave he did not own, because he would not own the children. Robert was savagely beaten and Truth never saw him again. Later, he died from the aforementioned injuries.[7] In 1817, Truth was forced by Dumont to marry an older slave named Thomas. She had five children: Diana (1815), fathered by Robert; and Thomas who died shortly after birth; Peter (1821); Elizabeth (1825); and Sophia (ca. 1826), fathered by Thomas.[8]

Freedom

The state of New York began, in 1799, to legislate the abolition of slavery, although the process of emancipating New York slaves was not complete until July 4, 1827. Dumont had promised to grant Truth her freedom a year before the state emancipation, "if she would do well and be faithful." However, he changed his mind, claiming a hand injury had made her less productive. She was infuriated but continued working, spinning 100 pounds of wool, to satisfy her sense of obligation to him.

Late in 1826, Truth escaped to freedom with her infant daughter, Sophia. She had to leave her other children behind because they were not legally freed in the emancipation order until they had served as bound servants into their twenties.[5] She later said:

I did not run off, for I thought that wicked, but I walked off, believing that to be all right.[5]

She found her way to the home of Isaac and Maria Van Wagener, who took her and her baby in. Isaac offered to buy her services for the remainder of the year (until the state's emancipation took effect), which Dumont accepted for $20.[5] She lived there until the New York State Emancipation Act was approved a year later.

Truth learned that her son Peter, then five years old, had been sold illegally by Dumont to an owner in Alabama. With the help of the Van Wageners, she took the issue to court and, after months of legal proceedings, got back her son, who had been abused by his new owner.[4] Truth became one of the first black women to go to court against a white man and win the case.[9] See also Elizabeth Freeman

Truth had a life-changing religious experience during her stay with the Van Wageners, and became a devout Christian. In 1829 she moved with her son Peter to New York City, where she worked as a housekeeper for Elijah Pierson, a Christian Evangelist. In 1832, she met Robert Matthews, also known as Matthias Kingdom or Prophet Matthias, and went to work for him as a housekeeper.[4] In a bizarre twist of fate, Elijah Pierson died, and Robert Matthews and Truth were accused of stealing from and poisoning him. Both were acquitted and Robert Matthews moved west.[5]

In 1839, Truth's son Peter took a job on a whaling ship called the Zone of Nantucket. From 1840 to 1841, she received three letters from him, though in his third letter he told her he had sent five. When the ship returned to port in 1842, Peter was not on board and Truth never heard from him again.[4]

"The Truth Calls Me"

On June 1, 1843, Truth changed her name to Sojourner Truth and told her friends, "The Spirit calls me, and I must go." She became a Methodist, and left to make her way traveling and preaching about the abolition of slavery. In 1844, she joined the Northampton Association of Education and Industry in Northampton, Massachusetts. Founded by abolitionists, the organization supported women's rights and religious tolerance as well as pacifism. There were 210 members and they lived on 500 acres (2.0 km2), raising livestock, running a sawmill, a gristmill, and a silk factory. While there, Truth met William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, and David Ruggles. In 1846, the group disbanded, unable to support itself.[5] In 1847, she went to work as a housekeeper for George Benson, the brother-in-law of William Lloyd Garrison. In 1849, she visited John Dumont before he moved west.[4]

Truth started dictating her memoirs to her friend Olive Gilbert, and in 1850 William Lloyd Garrison privately published her book, The Narrative of Sojourner Truth: A Northern Slave.[5] That same year, she purchased a home in Northampton for $300, and spoke at the first National Women's Rights Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts.

"Ain't I a Woman?"

In 1851, Truth left Northampton to join George Thompson, an abolitionist and speaker. In May, she attended the Ohio Women's Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio where she delivered her famous extemporaneous speech on women's rights, later known as "Ain't I a Woman". The convention was organized by Hannah Tracy and Frances Dana Barker Gage, who both were present when Truth spoke. Different versions of Truth's words have been recorded, with the first one published a month later by Marius Robinson, a newspaper owner and editor who was in the audience. Robinson's recounting of the speech included no instance of the question "Ain't I a Woman?" Twelve years later in May 1863, Gage published another, very different, version. In it, Truth's speech pattern had characteristics of Southern slaves, and the speech included sentences and phrases that Robinson didn't report. Gage's version of the speech became the historic standard, and is known as "Ain't I a Woman?" because that question was repeated four times.[10] Truth's own speech pattern was not Southern in nature, as she was born and raised in New York, and spoke only Dutch until she was nine years old.[11]

In contrast to Robinson's report, Gage's 1863 version included Truth saying her 13 children were sold away from her into slavery. Truth is widely believed to have had five children, with one sold away, and was never known to boast more children.[11] Gage's 1863 recollection of the convention conflicts with her own report directly after the convention: Gage wrote in 1851 that Akron in general and the press in particular were largely friendly to the woman's rights convention, but in 1863 she wrote that the convention leaders were fearful of the "mobbish" opponents.[11] Other eyewitness reports of Truth's speech told a calm story, one where all faces were "beaming with joyous gladness" at the session where Truth spoke; that not "one discordant note" interrupted the harmony of the proceedings.[11] In contemporary reports, Truth was warmly received by the convention-goers, the majority of whom were long-standing abolitionists, friendly to progressive ideas of race and civil rights.[11] In Gage's 1863 version, Truth was met with hisses, with voices calling to prevent her from speaking.[12]

Over the next decade, Truth spoke before dozens, perhaps hundreds, of audiences. From 1851 to 1853, Truth worked with Marius Robinson, the editor of the Ohio Anti-Slavery Bugle, and traveled around that state speaking. In 1853, she spoke at a suffragist "mob convention" at the Broadway Tabernacle in New York City; that year she also met Harriet Beecher Stowe.[4] In 1856, she traveled to Battle Creek, Michigan, to speak to a group called the Friends of Human Progress. In 1858, someone interrupted a speech and accused her of being a man; Truth opened her blouse and revealed her breasts.[4][5]

Other notable speeches

Mob Convention—September 7, 1853: At the convention, young men greeted her with “a perfect storm,” hissing and groaning. In response, Truth said, “You may hiss as much as you please, but women will get their rights anyway. You can’t stop us, neither”.[11] Sojourner, like other public speakers, often adapted her speeches to how the audience was responding to her. In her speech, Sojourner speaks out for women’s rights. She incorporates religious references in her speech, particularly the story of Esther. She then goes on to say that, just as women in scripture, women today are fighting for their rights. Moreover, Sojourner scolds the crowd for all their hissing and rude behavior, reminding them that God says to “Honor thy father and thy mother.” [13]

American Equal Rights Association—May 9–10, 1867: Her speech was addressed to the American Equal Rights Association, and divided into three sessions. Sojourner was received with loud cheers instead of hisses, now that she had a better-formed reputation established. The Call had advertised her name as one of the main convention speakers.[13] For the first part of her speech, she spoke mainly about the rights of black women. Sojourner argued that because the push for equal rights had led to black men winning new rights, now was the best time to give black women the rights they deserve too. Throughout her speech she kept stressing that “we should keep things going while things are stirring” and fears that once the fight for colored rights settles down, it would take a long time to warm people back up to the idea of colored women’s having equal rights.[13]

In the second sessions of Sojourner’s speech, she utilized a story from the Bible to help strengthen her argument for equal rights for women. She ended her argument by accusing men of being self-centered, saying, “man is so selfish that he has got women’s rights and his own too, and yet he won’t give women their rights. He keeps them all to himself.” For the final session of Sojourner’s speech, the center of her attention was mainly on women’s right to vote. Sojourner told her audience that she owned her own house, as did other women, and must therefore pay taxes. Nevertheless, they were still unable to vote because they were women. Black women who were slaves were made to do hard manual work, such as building roads. Sojourner argues that if these women were able to perform such tasks, then they should be allowed to vote because surely voting is easier than building roads.

Eighth Anniversary of Negro Freedom—New Year’s Day, 1871: On this occasion the Boston papers related that “…seldom is there an occasion of more attraction or greater general interest. Every available space of sitting and standing room was crowded”.[13] She starts off her speech by giving a little background about her own life. Sojourner recounts how her mother told her to pray to God that she may have good masters and mistresses. She goes on to retell how her masters were not good to her, about how she was whipped for not understanding English, and how she would question God why he had not made her masters be good to her. Sojourner admits to the audience that she had once hated white people, but she says once she met her final master, Jesus, she was filled with love for everyone. Once slaves were emancipated, she tells the crowd she knew her prayers had been answered. That last part of Sojourner’s speech brings in her main focus. Some freed slaves were living on government aid at that time, paid for by taxpayers. Sojourner announces that this is not any better for those colored people than it is for the members of her audience. She then proposes that black people are given their own land. Because a portion of the South’s population contained rebels that were unhappy with the abolishment of slavery, that region of the United States was not well suited for colored people. She goes on to suggest that colored people be given land out west to build homes and prosper on.

On a mission

Truth sold her home in Northampton in 1857 and bought a house in Harmonia, Michigan, just west of Battle Creek.[5] According to the 1860 census, her household in Harmonia included her daughter, Elizabeth Banks (age 35), and her grandsons James Caldwell (misspelled as "Colvin"; age 16) and Sammy Banks (age 8).[4]

During the Civil War, Truth helped recruit black troops for the Union Army. Her grandson, James Caldwell, enlisted in the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. In 1864, Truth was employed by the National Freedman's Relief Association in Washington, D.C., where she worked diligently to improve conditions for African-Americans. In October of that year, she met President Abraham Lincoln.[4] In 1865, while working at the Freedman's Hospital in Washington, Truth rode in the streetcars to help force their desegregation.[4]

Truth is credited with writing a song, "The Valiant Soldiers", for the 1st Michigan Colored Regiment; it was said to be composed during the war and sung by her in Detroit and Washington, D.C. It is sung to the tune of "John Brown's Body" or "The Battle Hymn of the Republic".[14] Although Truth claimed to have written the words, it has been disputed (see Marching Song of the First Arkansas).

In 1867, Truth moved from Harmonia to Battle Creek. In 1868, she traveled to western New York and visited with Amy Post, and continued traveling all over the East Coast. At a speaking engagement in Florence, Massachusetts, after she had just returned from a very tiring trip, when Truth was called upon to speak she stood up and said,

Children, I have come here like the rest of you, to hear what I have to say.[15]

In 1870, Truth tried to secure land grants from the federal government to former slaves, a project she pursued for seven years without success. While in Washington, D.C., she had a meeting with President Ulysses S. Grant in the White House. In 1872, she returned to Battle Creek and tried to vote in the presidential election, but was turned away at the polling place.

Truth spoke about abolition, women's rights, prison reform, and preached to the Michigan Legislature against capital punishment. Not everyone welcomed her preaching and lectures, but she had many friends and staunch support among many influential people at the time, including Amy Post, Parker Pillsbury, Frances Gage, Wendell Phillips, William Lloyd Garrison, Laura Smith Haviland, Lucretia Mott, and Susan B. Anthony."[15]

Several days before Truth died, a reporter came from the Grand Rapids Eagle to interview her. "Her face was drawn and emaciated and she was apparently suffering great pain. Her eyes were very bright and mind alert although it was difficult for her to talk." [4] Truth died on November 26, 1883, at her home in Battle Creek, Michigan, and was buried at Oak Hill Cemetery in Battle Creek, beside other family members.

Cultural references

- 1862—William Wetmore Story's statue, "The Libyan Sibyl", inspired by Sojourner Truth, won an award at the London World Exhibition.[5]

- 1892—Albion artist Frank Courter is commissioned to paint the meeting between Truth and President Abraham Lincoln.[4]

- 1981—Truth is inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York.[4]

- 1981—Feminist theorist and author bell hooks titles her first major work after Truth's "Ain't I a Woman?" speech.

- 1983—Truth is in the first group of women inducted into the Michigan Women's Hall of Fame in Lansing.[4]

- 1986—U.S. Postal Service issued a commemorative postage stamp honoring Sojourner Truth.[4][16]

- 1997—The NASA Mars Pathfinder mission's robotic rover was named "Sojourner" after her.[17]

- 1998—S.T. Writes Home appears on the web offering "Letters to Mom from Sojourner Truth," in which the Mars Pathfinder Rover at times echoes its namesake.

- 1999—The Broadway musical The Civil War includes Sojourner Truth: Ain't I a Woman. On the 1999 cast recording, it was performed by Maya Angelou.

- The leftist group the Sojourner Truth Organization is named after her.

- The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America commemorates her as a renewer of society on March 10, with Harriet Tubman.

- 2002—scholar Molefi Kete Asante lists Sojourner Truth on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[18]

- 2004—The King's College, located inside the Empire State Building in New York City, has a house system (modeled after Oxford University's), and each house is named after an influential leader. In 2004, they voted to name one of the houses 'The House of Sojourner Truth'.

- She is commemorated in a monument of "Michigan Legal Milestones" erected by the State Bar of Michigan.[19]

- She is also commemorated together with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Amelia Bloomer and Harriet Ross Tubman in the calendar of saints of the Episcopal Church on July 20.

- The Library at the State University of New York at New Paltz, in New Paltz, New York, is named in her honor.

- 2009—The first black woman honored with a bust in the US Capitol.[20] The bust was sculpted by noted artist Artis Lane.

Books

- Narrative of Sojourner Truth: A Northern Slave (1850).

- Dover Publications 1997 edition: ISBN 0-486-29899-X

- Penguin Classics 1998 edition: ISBN 0-14-043678-2. Introduction & notes by Nell Irvin Painter.

- University of Pennsylvania online edition (html format, one chapter per page)

- University of Virginia online edition (HTML format, 207 kB, entire book on one page)

- Alison Piepmeier, Out in Public: Configurations of Women's Bodies in Nineteenth-Century America The University of North Carolina Press, 2004) ISBN 0-80-785569-3

- Paul E. Johnson and Sean Wilentz, The Kingdom of Matthias: A Story of Sex and Salvation in 19th-Century America (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994) ISBN 0-19-509835-8

- Carleton Mabee with Susan Mabee Newhouse, Sojourner Truth: Slave, Prophet, Legend (New York and London: New York University Press, 1993) ISBN 0-8147-5525-9

- Nell Irvin Painter, Sojourner Truth: A Life, A Symbol (New York and London: W. W. Norton & Co., 1996) ISBN 0-393-31708-0

- Jacqueline Sheehan, Truth: A Novel (New York: Free Press, 2003) ISBN 0-7432-4444-3

- Erlene Stetson and Linda David, Glorying in Tribulation: The Lifework of Sojourner Truth (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1994) ISBN 0-87013-337-3

- Michael Warren Williams, The African American encyclopedia, Volume 6, Marshall Cavendish Corp., 1993, ISBN 1854355511

- William Leete Stone, Matthias and his Impostures- or, The Progress of Fanaticism (New York, 1835) Internet Archive online edition (pdf format, 16.9 MB, entire book on one pdf)

- Gilbert Vale, Fanaticism - Its Source and Influence Illustrated by the Simple Narrative of Isabella, in the Case of Matthias, Mr. and Mrs. B. Folger, Mr. Pierson, Mr. Mills, Catherine, Isabella, &c. &c. (New York, 1835) Google Books online edition (pdf format, 9.9 MB, entire book on one pdf or one page per page)[13]

References

- ^ The "ten or twelve" figure is from the section "Her brothers and sisters" in the Narrative (p. 10 in the 1998 Penguin Classics edition edited by Nell Irvin Painter); it is also used in Painter's biography, Sojourner Truth: A Life, A Symbol (Norton, 1996), p. 11; and in Carleton Mabee with Susan Mabee Newhouse's biography, Sojourner Truth: Slave, Prophet, Legend (New York University Press, 1993), p. 3.

- ^ Michael Warren Williams (1993), p. 1581

- ^ Whalin, W. Terry (199ŵ7). Sojourner Truth. Barbour Publishing, Inc. ISBN 9781593106294.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|coauthors=and|month=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Amazing Life page". Sojourner Truth Institute site. Retrieved December 28, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Sojourner Truth page". Women in History site. Retrieved December 28, 2006.

- ^ "State University of New York at New Paltz". On the trail of Sojourner Truth in Ulster County, New York by Corinne Nyquist Librarian, Sojourner Truth Library. Retrieved March 6, 2008.

- ^ "Sojourner Truth page". Narrative of Sojourner Truth. Retrieved December 28, 2006.

- ^ Nell Irvin Painter, Sojourner Truth: A Life, A Symbol (Norton, 1996), p. 19.

- ^ Memory.loc.gov

- ^ Craig, Maxine Leeds. Ain't I A Beauty Queen: Black Women, Beauty, and the Politics of Race, Oxford University Press USA, 2002, p. 7. ISBN 0-19-515262-X

- ^ a b c d e f Mabee, Carleton; Susan Mabee Newhouse. Sojourner Truth: Slave, Prophet, Legend, NYU Press, 1995, pp. 67–82. ISBN 0-8147-5525-9

- ^ Stanton, Elizabeth Cady; Anthony, Susan Brownell; Gage, Matilda Joslyn. History of Woman Suffrage, Volume I, pp. 115–116, covering 1848–1861. Copyright 1881.

- ^ a b c d e Montgomery, Janey (1968). A Comparative Analysis of the Rhetoric of Two Negro Women Orators—Sojourner Truth and Frances E. Watkins Harper. Hays, Kansas: Fort Hays Kansas State College. pp. 25–103.

- ^ "Documenting the American South". Narrative of Sojourner Truth. Retrieved November 7, 2007.

- ^ a b "Sojourner Truth page". Sojourner Truth Biography. Archived from the original on 2005-12-22. Retrieved December 28, 2006.

- ^ Scott catalog # 2203, first day of issue on February 4, 1986.

- ^ NASA, NASA Names First Rover to Explore the Surface of Mars. Accessed December 4, 2006.

- ^ Asante, Molefi Kete (2002). 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Amherst, New York. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-963-8.

- ^ State Bar of Michigan.

- ^ PRNewswire. Pelosi Remarks at Sojourner Truth Bust Unveiling, Retrieved on April 28, 2009.

Further reading

- Washington, Margaret (2009). Sojourner Truth's America. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-03419-0. Paperback, 2011.

External links

- Works by Sojourner Truth at Project Gutenberg

- Sojourner Truth: Online Resources, from the Library of Congress

- On the trail of Sojourner Truth SUNY New Paltz, Sojourner Truth Library

- Sojourner Truth Institute

- Poem form of Ain't I a Woman?

- Bio at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis Learning to Give site

- Narrative of Sojourner Truth, a Northern Slave, Emancipated from Bodily Servitude by the State of New York, in 1828. Boston: The Author, 1850.

- Narrative of Sojourner Truth; a Bondswoman of Olden Time, Emancipated by the New York Legislature in the Early Part of the Present Century; with a History of Her Labors and Correspondence, Drawn from Her "Book of Life" Boston: For the Author, 1875.

- Narrative of Sojourner Truth; a Bondswoman of Olden Time, Emancipated by the New York Legislature in the Early Part of the Present Century; with a History of Her Labors and Correspondence Drawn from Her "Book of Life;" Also, a Memorial Chapter, Giving the Particulars of Her Last Sickness and Death. Battle Creek, Mich.: Review and Herald Office, 1884.

- The Narrative of Sojurner Truth from American Studies at the University of Virginia

- Sojourner Truth at Find a Grave

- Sojourner Truth at C-SPAN's American Writers: A Journey Through History

- Booknotes interview with Nell Irvin Painter on Sojourner Truth: A Life, A Symbol, December 8, 1996.

- Ill-formatted IPAc-en transclusions

- 1797 births

- 1883 deaths

- People from Ulster County, New York

- American Methodists

- American abolitionists

- American people of Ghanaian descent

- American people of Guinean descent

- American slaves

- American suffragists

- Anglican saints

- People celebrated in the Lutheran liturgical calendar

- People of Michigan in the American Civil War

- Women in the American Civil War

- People acquitted of murder

- People from Northampton, Massachusetts

- People from Battle Creek, Michigan

- Black feminism

- Feminism and history

- 19th-century Christian female saints

- African American female activists