MDMA: Difference between revisions

→Use in psychotherapy: clarified expertise |

|||

| Line 143: | Line 143: | ||

==Use in psychotherapy== |

==Use in psychotherapy== |

||

Some scientists<ref>http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/health/article3850302.ece</ref> have suggested that MDMA may facilitate self-examination with reduced fear, which may prove useful in a therapeutic setting. Individuals[http://www.maps.org], including Rick Doblin, have suggested that MDMA-assisted psychotherapy could provide "gentle yet profound long-term growth."<ref> Doblin, R. ( 2002) A clinical plan for MDMA (ecstasy) in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Partnering with the FDA. J. Psychoactive Drugs, 35, 185–194.</ref> |

Some scientists<ref>http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/health/article3850302.ece</ref> have suggested that MDMA may facilitate self-examination with reduced fear, which may prove useful in a therapeutic setting. Individuals[http://www.maps.org], including Rick Doblin (Ph.D., public policy), have suggested that MDMA-assisted psychotherapy could provide "gentle yet profound long-term growth."<ref> Doblin, R. ( 2002) A clinical plan for MDMA (ecstasy) in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Partnering with the FDA. J. Psychoactive Drugs, 35, 185–194.</ref> |

||

A small number of therapists, including George Greer, Joseph Downing, and Philip Wolfson, used it in their practices until it was made illegal. George Greer synthesized MDMA in the lab of Alexander Shulgin and administered it to about 80 of his clients over the course of the remaining years preceding MDMA's Schedule I placement in 1985. In a published summary of the effects,<ref>{{cite journal |title= Subjective Reports of the Effects of MDMA in a Clinical Setting |author= Greer, G.; Tolbert, R. | journal= Journal of Psychoactive Drugs |volume= 18 |issue= 4 |pages= 319–327 |year= 1986 |url= http://www.heffter.org/pages/subjrep.html |format=reprint }}</ref> the authors reported patients felt improved in various, mild psychiatric disorders and other personal benefits, especially improved intimate communication with their significant others. In a subsequent publication on the treatment method, the authors reported that one patient with severe pain from terminal cancer experienced lasting pain relief and improved quality of life. <ref>{{cite journal |title= A Method of Conducting Therapeutic Sessions with MDMA |author= Greer, G.; Tolbert, R. |journal= Journal of Psychoactive Drugs |volume= 30 |issue= 4 |pages=371–379 |year= 1998 |url= http://www.heffter.org/pages/sessions.html |format= reprint }}</ref> However, few of the results in this early MDMA psychotherapy were measured using methods considered reliable or convincing in scientific practice. For example, the questionnaires used might not have been sensitive to negative changes and it is not known to what extent similar patients might improve from chance or from psychotherapy. |

A small number of therapists, including George Greer, Joseph Downing, and Philip Wolfson, used it in their practices until it was made illegal. George Greer synthesized MDMA in the lab of Alexander Shulgin and administered it to about 80 of his clients over the course of the remaining years preceding MDMA's Schedule I placement in 1985. In a published summary of the effects,<ref>{{cite journal |title= Subjective Reports of the Effects of MDMA in a Clinical Setting |author= Greer, G.; Tolbert, R. | journal= Journal of Psychoactive Drugs |volume= 18 |issue= 4 |pages= 319–327 |year= 1986 |url= http://www.heffter.org/pages/subjrep.html |format=reprint }}</ref> the authors reported patients felt improved in various, mild psychiatric disorders and other personal benefits, especially improved intimate communication with their significant others. In a subsequent publication on the treatment method, the authors reported that one patient with severe pain from terminal cancer experienced lasting pain relief and improved quality of life. <ref>{{cite journal |title= A Method of Conducting Therapeutic Sessions with MDMA |author= Greer, G.; Tolbert, R. |journal= Journal of Psychoactive Drugs |volume= 30 |issue= 4 |pages=371–379 |year= 1998 |url= http://www.heffter.org/pages/sessions.html |format= reprint }}</ref> However, few of the results in this early MDMA psychotherapy were measured using methods considered reliable or convincing in scientific practice. For example, the questionnaires used might not have been sensitive to negative changes and it is not known to what extent similar patients might improve from chance or from psychotherapy. |

||

Revision as of 17:58, 28 June 2008

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Sublingual salla |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic, CYP extensively involved |

| Elimination half-life | The half-life of MDMA is dose dependent, increasing with higher doses, but is around 6–10 hours at doses of 40–125 mg |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

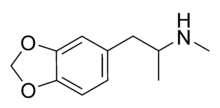

| Formula | C11H15NO2 |

| Molar mass | 193.25 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine), most commonly known today by the street name Ecstasy (often abbreviated E, X, or XTC), is a semisynthetic member of the amphetamine[2] class of psychoactive drugs, a subclass of the phenethylamines[3]. MDMA also falls under many other broad categories of substances, including stimulants, psychedelics, and the empathogenic-entactogens.

MDMA's primary effects are more consistent than those produced by most psychedelics, and its incumbent euphoria appears to be characteristically distinct from that of most stimulants. It is also considered unusual for its tendency to produce a sense of intimacy with others as well as diminished feelings of fear and anxiety.

MDMA is criminalized in all countries in the world under a UN agreement[4], and its possession, manufacture, or sale may result in criminal prosecution. MDMA is one of the most widely used illicit drugs in the world and is taken in a variety of contexts far removed from its roots in psychotherapeutic settings. It is commonly associated with the rave culture and its related genres of music.

There are concerns within science, health care, and drug policy circles that MDMA may lead to neurotoxic damage of the central nervous system, the presence, reversibility, extent and significance of which are yet to be determined[5][6]. Based on these and other health concerns, there are suggestions that the risks of even single doses of MDMA outweigh its potential benefits[7][8]. These concerns, however, are not based on conclusive evidence, and MDMA is therefore deemed to require further study[9][10].

Before it was made a controlled substance, MDMA was used to aid psychotherapy, often couples therapy, the results of which are poorly documented. Studies have also recently been initiated to examine the therapeutic potential of MDMA for posttraumatic stress disorder and anxiety associated with cancer. In addition, several research groups are using it in humans for basic scientific research.[11]

History

At the end of the 19th century, the Merck company of Germany was interested in developing substances that stopped abnormal bleeding. One of the most important compounds was hydrastinine. The plant from which it was isolated became rarer, and they started looking for alternatives. The scientific reports from the laboratory from 1911 and 1912 show that they wanted to use 3-methyl-hydrastinine as an alternative. They believed that this methylated analog of hydrastinine might be similarly effective. Drs. Walther Beck, Otto Wolfes and Anton Köllisch started on the project. In the newly developed synthetic pathway to 3-methyl-hydrastinine, MDMA was mentioned as one of several key precursors under the name of Methylsafrylamin. In 1912 Dr. Anton Köllisch was requested to develop a patentable synthesis for 3-methyl-hydrastinine. The patent started on December 24, 1912. It is a procedural patent for compounds which are key precursors for therapeutics. MDMA was not the purpose of the patent. It was Dr. Max Oberlin (also at Merck) who in 1927 was the first person interested in the pharmacological properties of MDMA. Research on the substance was stopped for economic reasons, and the substance was buried in oblivion for some decades. In the 1950s the American and German armies were interested in psychotropic agents; MDMA was among the tested substances. Most probably for this reason, MDMA was re-synthesized at Merck. In his laboratory journal of 1952 Dr. Albert van Schoor describes how MDMA kills 6 flies in 30 minutes. In 1959 Dr. Fruhstorfer works on MDMA and similar psychotropics, his substance H671 was identified to be MDMA. The research on these substances led to the marketing of Reaktivin in 1960. Its chemical structure is not related to MDMA. The first scientific paper on MDMA appeared in 1960 and described a synthesis for MDMA. It is written in Polish by Biniecki and Krajewski and almost unknown. In 1978 Alexander Shulgin published the first scientific article on the drug’s psychotropic effect in humans.[12]

The U.S. Army did, however, carry out lethal dose studies of MDMA and several other compounds on animals in the mid-1950s. It was given the name EA-1475, with the EA standing for either (accounts vary) "Experimental Agent" or "Edgewood Arsenal."[13] The results of these studies were not declassified until 1969.

MDMA first appeared sporadically as a street drug in the early 1970s after its counterculture analogue, MDA, became criminalized in the United States in 1970.[14] MDMA use, however, remained very limited until the end of the decade. MDMA began to be used therapeutically in the late-1970s after noted chemist Alexander Shulgin tried it himself, in 1977,[15] and subsequently introduced it to psychotherapist Leo Zeff. As Zeff and others spread word about MDMA, it developed a reputation for enhancing communication during clinical sessions, reducing patients' psychological defenses, and increasing capacity for therapeutic introspection. However, no formal measures of these putative effects were made and blinded or placebo-controlled trials were not conducted. A small number of therapists, including George Greer, Joseph Downing, and Philip Wolfson, used it in their practices until it was made illegal. Other therapists continued to conduct therapy illegally and MDMA was not legally given to humans until Charles Grob initiated an ascending-dose safety study in healthy volunteers. Subsequent legally-approved MDMA studies in humans have taken place in Detroit, Chicago, San Francisco, and South Carolina, as well as in Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Spain.[16]

Due to the wording of the United Kingdom's existing Misuse of Drugs Act of 1971, MDMA was automatically classified as a Class A drug in 1977.

In the early 1980s in the United States, MDMA rose to prominence in trendy nightclubs in the Dallas area, then in gay dance clubs.[17] From there use spread to rave clubs in major cities around the country, and then to mainstream society. The drug was first proposed for scheduling by the DEA in July 1984,[18] and was classified as a Schedule I controlled substance in the United States from May 31, 1985.[19]

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, ecstasy was widely used in the United Kingdom and other parts of Europe, becoming an integral element of rave culture and other psychedelic/dancefloor-influenced music scenes, such as Madchester and Acid House. Spreading along with rave culture, illicit MDMA use became increasingly widespread among young adults in universities and later in high schools. MDMA became one of the four most widely used illicit drugs in the United States, along with cocaine, heroin and cannabis.[citation needed] Today in the US, according to some estimates, only cannabis will attract more first-time users.[20]

Effects

Mode of action

The mechanism of MDMA's unusual effects has yet to be fully understood, although it is generally thought that the primary relevant pharmacological characteristic of the drug is its affinity for SERTs. SERTs are the part of the serotonergic neuron which remove serotonin from the synapse to be recycled or stored for later use. Not only does MDMA inhibit the reuptake of serotonin into this pump, but it reverses the action of the transporter so that it begins pumping serotonin into the synapse from inside the cell.[2] In addition, MDMA induces the release of norepinephrine and dopamine.[21]

MDMA's unusual empathic/entactogenic effects have been hypothesized to be at least partly the result of the release of oxytocin,[22] a hormone usually released following such events as orgasm and childbirth, which is thought to facilitate bonding and the establishment of trust. MDMA is thought to cause this release by indirectly stimulating 5-HT1A receptors. However, the evidence that oxytocin is involved in the effects of MDMA is derived from studies conducted on rats where the emotional effects can only be indirectly measured, in this case by the time animals spend in close proximity to one another. Controlled human studies have not yet been carried out, and it is not known conclusively if MDMA has oxytocinergic action in humans. The question of why other serotonergic drugs do not produce a similarly profound emotional state like MDMA also remains unanswered.

Acute effects

The primary effects attributable to MDMA consumption are predictable and fairly consistent amongst users.[3] [4] [5] The most common effects include:

- Euphoria

- Decreased hostility and insecurity

- Increased feelings of intimacy with others

- Feelings of empathy towards others

- Ability to discuss anxiety-provoking topics with markedly-increased ease

- A strong sense of inner peace and self-acceptance

- Feelings of insightfulness and mental clarity

- Intensification of sensory experience, particularly auditory and tactile

- Decreased appetite

- Urinary retention (also see hyponatremia)

- Mydriasis (abnormal pupil dilation)

- Increased physical energy

- Increased heart rate and blood pressure

Other effects may include:

- Short-term memory lapses

- Trisma (lockjaw)

- Bruxia (involuntary teeth grinding)

- Nystagmus (rapid, uncontrollable eye movements)

- Several hours of restlessness following primary subjective effects, often accompanied by a peaceful, "glowing" feeling

- A period of general malaise following primary subjective effects, normally resolving within a few days

- Mildly-blurred vision following primary subjective effects, gradually resolving over a period of up to several days, also known as "plurring"

Serious complications increasing in likelihood with dose, environmental severity, degree of physical activity, and/or certain drug interactions include:

- Hyperthermia (due to an intemperate environment and/or lack of hydration and/or rest from physical activity, usually dancing)

- Dehydration (due to an intemperate environment and/or lack of hydration and/or rest from physical activity, usually dancing)

- Hyponatremia (due to drug induced antidiuretic hormone release and/or excess compensatory intake of fluids, a rare complication)

- Serotonin syndrome (believed to be due to excess release of serotonin, sometimes triggered by coadministration of other serotonergic drugs)

Effects of chronic use

The long-term health effects of ecstasy use are generally not well-known, and the research that has been devoted to addressing the relevant issues thus far has been largely inconclusive. The primary concern is generally that there may be negative long-term consequences that result from the drug's alleged neurotoxic effects on serotonergic neurons.[23] Some further studies have also shown that this damage causes increased rates of depression and anxiety, even after quitting the drug.[24][25] In addition to this, some studies have indicated that MDMA may cause long-term memory and cognition impairment. [26] Many factors, including total lifetime MDMA consumption, the duration of abstinence between uses, the environment of use, poly-drug use/abuse, quality of mental health, various lifestyle choices, and predispositions to develop clinical depression and other disorders may contribute to various possible health consequences. MDMA use has been occasionally associated with liver damage[27], excessive wear of teeth[28], and Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder[29].

Controversy surrounding research

Research into the neurotoxic effects of MDMA has been highly controversial because of the possible influence of political pressures on the science. Government institutions, as part of a struggle to get ecstasy off the streets, often assert that the drug causes irreparable brain damage. Popular claims that MDMA drains spinal fluid or causes holes in the brain are scientifically unfounded. Much research on the long-term effects of the drug has been funded by government grants and has been used to fuel the National Institute on Drug Abuse's (NIDA) "Brain on Ecstasy" anti-ecstasy campaign. The campaign's widely distributed postcard shows two halves of a brain, one normal and one "after ecstasy." The brain of the ecstasy user appears darker and has holes, which has led to the common misconception that brain imaging studies prove ecstasy creates holes in your brain. A DEA agent interviewed in Peter Jennings's documentary Ecstasy Rising goes so far as to say that ecstasy "turns your brain into Swiss cheese"[30]. However, there are major flaws in this interpretation, the most obvious being that the images shown are not structural brain images, and don't show any holes. Instead, what they actually depict are subtle, relative differences in some marker of neural activity, a more ambiguous finding. Brain imaging studies here and in other domains are notoriously misinterpreted and over-generalized by the media and general public.

One major PET study published by McCann et al. concludes that MDMA use is associated with deficits in serotonin neurons all over the brain, which may lead to functional consequences such as depression, anxiety or memory problems[31]. While this finding may have some merit, misinterpretations of these PET images have contributed to the "holes in your brain" propaganda. Additionally, the study has been criticized for multiple methodological issues, such as including users of multiple drugs whose effects are unknown, and high variability within groups[32]. In a study published a few years later by some of the same researchers, Ricaurte et al. claim common recreational doses of ecstasy can cause Parkinson's disease based on their work with non-human primates[33]. The paper was later retracted after the discovery that they had accidentally administered methamphetamine, not MDMA, to all but one of their animals [34]. These kinds of flaws in the scientific literature on the effects of ecstasy contribute to the distrust of this entire area of research, however valid, among the users and the public.

Misinterpretations of scientific data on the effects of ecstasy use have appeared in the media. One such case occurred on an MTV special on Ecstasy (November 28, 2000) [35]. During the special, doctors of an ecstasy user reported the patient's brain scans showed "holes in the brain" like one would expect to see in a stroke victim. This was a misrepresentation of the image, which did not show structural holes, but instead differences in relative blood flow.

Research outside of the United States, where ecstasy may be decriminalized, may be subject to less political pressure. The initial findings of a massive research project (NeXT) funded by the Netherlands government were published in 2006.[36] The project tracks ecstasy users in an attempt to determine the psychological and neurological effects of ecstasy use. The initial findings reported no structural neuronal damage from first time ecstasy use. However, a relative decrease of blood volume was found in some brain areas after just a single use. Behaviourally, subjects showed increased impulsivity and decreased depression. These results could be interpreted in many ways, but the authors conclude that "it is impossible to state, based on this study, that incidental use of ecstasy is totally safe for the brain."

Recreational use

MDMA use has increased markedly since the late 1980s, and spread beyond its original subcultures to mainstream use, with prices generally falling, although there is still wide geographical variance, both regionally and between countries.

According to the United States Drug Enforcement Administration’s drug information and the results of Monitoring the Future for 2004 and 2005 around 3% of 8th graders, around 4% of 10th graders, and around 6% of 12th graders reported MDMA use. [37]

In 2007, MDMA was the only drug reported to have in increase in use among 8th, 10th, and 12th graders. Simultaneously, perceived risk and disapproval ratings have declined among these students.[38]

United Kingdom

In 1995 it was reported that the street price per pill in the United Kingdom was "about £15 each,"[39] although two years later this had shifted to a range of £8 to £15 each.[40] A 2001 Home Office study reported that the cost per pill to end-point consumer, "could be as little as £7.50, or as much as £10 to £15 when purchased in clubs."[41]

In 2007 the Greater London Authority highlighted regional variations, reporting on the average street price per pill in five selected cities.[42] They were:

- Bristol £5

- London £3.50

- Manchester £3

- Nottingham £2

- Torquay £1.50

Supply

Worldwide, almost all MDMA is supplied via clandestine routes. The synthesis of MDMA is more complex than that of analogues such as methamphetamine, but still well within the grasp of a university-level chemistry student. Arguably, the most difficult part of the synthesis is obtaining the necessary chemical precursors, some of which have few legitimate uses outside of clandestine drug production. Distribution of many of these precursors is now heavily monitored by government agencies like the DEA.

Ecstasy pills

Pills come in a variety of "brands or batches", usually identified by the icons stamped on the pills. The purpose of this is to help identify and providing an indicator as to the strength and quality of a particular tablet. Many popular icons are appropriated for this use; an example would be "Red Mercedes", which derives its name from its red color and imprinted Mercedes-Benz logo. However, the brands do not consistently designate the actual active compound(s) within the pill, as it is possible for copycat manufacturers to make their own pills which replicate the appearance of a well-known brand.

MDMA powder/crystals

MDMA powder, usually the hydrochloride salt, is often simply called "crystal," "molly," or "mandy," and in the UK, "Muds," "Mud," or "madman" (a play on words: MaDMAn), a mutation of "madman," "mandy," and "MD." This powder is produced in MDMA labs and provided to the pill-manufacturers to press the tablets into their desired form. When pressed into pill tablets, MDMA powder is always mixed with pill binders because pure MDMA cannot be pressed.

In many parts of the world the usage of plain MDMA powder instead of pills is popular. One of the reasons for this is likely the superior control over dose and purity that the user is granted. This is because the powder form is less likely to be cut due to the greater ease of detecting impurities, and also because of MDMA's distinctive, intensely bitter taste. Because of this unpleasant taste, many users choose to "bomb" or "parachute" pure MDMA, whereby a dose is wrapped in cigarette papers or a small piece of toilet paper and then swallowed.

MDMA powder can also be insufflated, a route which leads to a quicker onset and dissipation of more intense effects, although users claim that this method of administration can be very unpleasant due to an intense burning sensation in the nose or throat.

Use in psychotherapy

Some scientists[43] have suggested that MDMA may facilitate self-examination with reduced fear, which may prove useful in a therapeutic setting. Individuals[6], including Rick Doblin (Ph.D., public policy), have suggested that MDMA-assisted psychotherapy could provide "gentle yet profound long-term growth."[44]

A small number of therapists, including George Greer, Joseph Downing, and Philip Wolfson, used it in their practices until it was made illegal. George Greer synthesized MDMA in the lab of Alexander Shulgin and administered it to about 80 of his clients over the course of the remaining years preceding MDMA's Schedule I placement in 1985. In a published summary of the effects,[45] the authors reported patients felt improved in various, mild psychiatric disorders and other personal benefits, especially improved intimate communication with their significant others. In a subsequent publication on the treatment method, the authors reported that one patient with severe pain from terminal cancer experienced lasting pain relief and improved quality of life. [46] However, few of the results in this early MDMA psychotherapy were measured using methods considered reliable or convincing in scientific practice. For example, the questionnaires used might not have been sensitive to negative changes and it is not known to what extent similar patients might improve from chance or from psychotherapy.

LSD, another psychedelic drug, also has a history of use in psychotherapy. Osmond and Hoffer hypothesized that LSD could be beneficial for schizophrenic patients and began conducting experiments using the drug. Erika Dyck suggests that there were two reasons for the failure of LSD to be considered beneficial in psychotherapy. One being that the method used by Osmond and Hoffer to study the drug and its effects became inadequate as a form of clinical testing. The other was that LSD, being heavily entangled in the revolution of the 1960’s, was not culturally accepted in America[47].

Similarly, this cultural unacceptance could be a reason why MDMA use in psychotherapy has not been seriously considered. Individuals like Ben Sessa, David J. Nutt, John H. Halpern and organizations like MAPS have recently been reconsidering the potential of MDMA in psychotherapy, for advanced stage cancer patients as well as for post-traumatic stress disorder. Halpern argues that the mental and physical effects of MDMA can be relieving and therapeutic for cancer patients[48] [49].

An ongoing study by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies is evaluating the efficacy of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for treating those diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder. To participate, patients must have had the disorder for a number of years and tried other treatments without success. In a newspaper interview, the researchers report promising tendencies for some participants to have reduced disease severity after MDMA psychotherapy.[50] However, despite the initially positive nature of the results, they are only press reports of individual participants in a currently-unpublished Phase II study, and similar research by other scientists will need to be conducted in order to demonstrate the efficacy of MDMA as a psychotherapeutic agent.

Still, MDMA for psychotherapeutic use has its critics. A.C. Parrott reminds that MDMA is powerful and affects neurotransmitter pathways and can intensify psychobiological functions. He argues that although there has been shown to be positive effects when using this drug, the negative effects cannot be ignored. Parrott cautions researchers stating that environmental factors are difficult to control and can effect a patient’s experience on the drug. Parrott also highlights that once the affects of MDMA begin to wear off, “there is a period of neurotransmitter recovery when low moods predominate, and these may exacerbate psychiatric distress. From either side, it is clear that MDMA should be further researched before any decision is made regarding its use in psychotherapy[51].

Synthesis

Safrole, a colorless or slightly yellow oil, extracted from the root-bark or the fruit of sassafras plants is the primary precursor for all manufacture of MDMA. There are numerous synthetic methods available in the literature to convert safrole into MDMA via different intermediates. One common route is via the MDP2P (3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl-2-propanone, also known as piperonyl acetone) intermediate. This intermediate can be produced in at least two different ways. One method is to isomerize safrole in the presence of a strong base to isosafrole and then oxidize isosafrole to MDP2P. Another, reportedly better method, is to make use of the Wacker process to oxidize safrole directly to the MDP2P (3,4-methylenedioxy phenyl-2-propanone) intermediate. This can be done with a palladium catalyst. Once the MDP2P intermediate has been produced it is then consumed via a reductive amination to form MDMA as the product.

According to DEA Microgram newsletters very little safrole is actually required to make MDMA.[52] "Ocotea cymbarum is an essential oil... that typically contains between 80 and 94 percent safrole," "a 500-milliliter bottle of Ocotea cymbarum sells for $20 to more than $100," "An MDMA producer with access to the proper chemicals can use a 500-milliliter quantity of Ocotea cymbarum to produce an estimated 1,300 to 2,800 tablets containing 120 milligrams of MDMA."

Legal issues

MDMA is illegal in most of the world under the UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances and other international agreements, although some limited exceptions exist for research. Generally, the use, sale or manufacture of MDMA are all criminal offenses.

In the United States, MDMA was legal and unregulated until May 31, 1985, at which time it was added to DEA Schedule I, for drugs deemed to have no medical uses and a high potential for abuse. During DEA hearings to criminalize MDMA, most experts recommended DEA Schedule III prescription status for the drug, due to its beneficial usage in psychotherapy. The judge overseeing the hearings, Francis Young, also made this recommendation. Nonetheless, the DEA classified it as Schedule I.[53]

That same year, the World Health Organization's Expert Committee on Drug Dependence recommended that MDMA be placed in Schedule I of the Convention on Psychotropic Substances. Unlike the Controlled Substances Act, the Convention has a provision in Article 7(a) that allows use of Schedule I drugs for "scientific and very limited medical purposes." The committee's report stated:[54]

- The Expert Committee held extensive discussions concerning therapeutic usefulness of 3,4 Methylenedioxymethamphetamine. While the Expert Committee found the reports intriguing, it felt that the studies lacked the appropriate methodological design necessary to ascertain the reliability of the observations. There was, however, sufficient interest expressed to recommend that investigations be encouraged to follow up these preliminary findings. To that end, the Expert Committee urged countries to use the provisions of article 7 of the Convention on Psychotropic Substances to facilitate research on this interesting substance.

In the United Kingdom, MDMA is a Class A drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, making it illegal to sell, buy, or possess without a license. Penalties include a maximum of seven years and/or unlimited fine for possession; life and/or unlimited fine for production or trafficking.

Health concerns

While the short-term adverse effects and contraindications of MDMA are fairly well known, there is significant debate within the scientific and medical communities possible regarding long-term physical and psychological effects of MDMA.

UK government assessment of overall harm

The chief executive of the UK Medical Research Council stated that MDMA is "on the bottom of the scale of harm," and was rated to be of lesser concern than alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis, as well as several classes of prescription medications, when examining the harmfulness of twenty popular recreational drugs. The UK study placed great weight on the risk for acute physical harm, the propensity for physical and psychological dependency on the drug, and the negative familial and societal impacts of the drug. Based on these factors, the study placed MDMA at number 18 in the list. [7]

Physical

The short-term physical health risks of MDMA consumption include hyperthermia [55] [56], and hyponatremia.[57] These dangers usually manifest themselves within the context of the rave subculture, as dancing often occurs in untempered environments where hundreds or even thousands of people are gathered in close proximity, sometimes indoors. Continuous dancing without sufficient rest or rehydration may cause body temperature to rise to dangerous levels, and loss of fluid via excessive perspiration puts the body at further risk as the stimulatory and euphoric qualities of the drug may render the user oblivious to their energy expenditure for quite some time. Diuretics such as alcohol and caffeine, also a stimulant, may exacerbate these risks further.

Hyponatremia (abnormally low salts in the blood) has been reported in some MDMA users. It is not clear to what extent this is due to the known ability of MDMA to induce antidiruetic hormone release and/or whether these people inadvertently consumed excess fluids in an attempt to remain hydrated. MDMA on its own does not cause dehydration and there is no need to drink extra fluids unless one has extra fluid loss, such as from sweating. Premenopausal females experiencing rapidly developing hyponatremia are at risk of neurological complications including seizures, coma, and death because hyponatremia can cause neurons to swell and stop working. MDMA-releated hyponatremia is relatively uncommon.

Hypertension is a risk in some users due to the increase in heart rate and blood pressure, but this is normally well-tolerated in young, healthy individuals who do not have pre-existing cardiovascular vulnerabilities.

Neurological overview

MDMA causes a reduction in the concentration of serotonin transporters (SERTs) in the brain. The rate at which the brain recovers from serotonergic changes is unclear. A number of studies [58], including some performed by George Ricaurte at Johns Hopkins University, have demonstrated lasting serotonergic changes occurring due to MDMA exposure. Baboons who were given a neurotoxic dose of MDMA showed partial regrowth of SERTs when scanned a year later.[59] Human users also show some recovery of serotonergic markers and, in some PET studies, have been indistinguishable from non-users. However, the same study also concluded that the reduction in memory performance due to heavy, prolonged MDMA use may be long-lasting.[60]

Although oxidative stress (see neurotoxicity theory below) may cause SERTs to degrade faster than they are able to be replaced, the serotonin axon itself seems to have been spared[dubious – discuss], which indicates that neurotoxicity may not be the means by which SERT count was reduced. It is possible that excess serotonin in the synapse due to MDMA, especially if uses occur within a short period, causes the serotonin cells to produce fewer SERTs, a phenomenon which has already been demonstrated with other serotonin-depleting drugs.[61] MDMA use may also cause a decrease in the number of serotonin receptors on the dendrite of the neuron. (See down-regulation theory below.)

For a detailed and comprehensive explanation of this topic, see TheDea.org's evaluation of studies.[62]

Receptor down-regulation

One theory of SERT-depletion arising out of long-term MDMA use is receptor down-regulation which is one form of synaptic plasticity. When any neurotransmitter is present in excess for prolonged periods of time, the brain responds in an attempt to reestablish its own natural neuro-electrical balance. Weekly use of MDMA over a prolonged period may actually cause serotonin receptors to retreat into the dendrite of serotonin nerve cells. [63] The change in synaptic serotonin concentration due to recreational MDMA use is at the extreme end of what is even possible in the brain and therefore, down-regulation could occur fairly easily with regular use. [citation needed]

This process causes the brain to become desensitized to the neurotransmitters present in the synapses and therefore also to the effects of MDMA itself. Therefore, in addition to a generally decreased quality of mood between doses[citation needed], greater amounts of MDMA are required to achieve the same level of desired effects. It is this cycle that is often believed to be the cause of long-term emotional problems among regular ecstasy users[citation needed].

Neurotoxicity

Under another theory, MDMA is considered neurotoxic in humans. While the method of this toxicity has not been definitively established, one theory is that the metabolism of MDMA-induced dopamine release leads to the lipid peroxidation of the axons of serotonergic neurons. This occurs when MAO-B metabolizes dopamine into free radicals capable of damaging cells, leading to a reduction in SERT count and damaging or destroying the axon, thus interfering with the integrity of the brain's serotonin network.[64][65] Neurotoxicity of serotonergic neurons would occur in selective areas of the human brain as serotonin cells are highly concentrated in certain areas such as the neocortex and hippocampus.

Normally, the brain is able to protect itself from oxidative stress, but it is believed that the aforementioned damage can be partially attributed to MDMA's unique interaction with serotonin transporters. Not only does MDMA reverse the normal functioning of the transporter in which case serotonin is pumped out of the cell, but once the stored serotonin has been depleted, the transporter begins to take up dopamine which has been shown to be toxic to serotonin cells by itself. Once MAO oxidizes dopamine inside the serotonin cell, the damage is greatly magnified. Several studies have demonstrated that such damage in the brain is reversible after prolonged abstinence from the drug.[66][67]

One now infamous study on the MDMA toxicity, which claimed that a single recreational dose of MDMA could cause Parkinson's Disease in later life due to severe dopaminergic stress, was actually retracted by Ricaurte himself after he discovered his lab had administered not MDMA but methamphetamine, which is known to cause dopaminergic changes similar to the serotonergic changes caused by MDMA.[68] Ricaurte blamed this mistake on the chemical supply company that sold the material to his lab. Most studies have found that levels of the dopamine transporter (or other markers of dopamine function) in MDMA users are normal.

Antioxidants have been shown to prevent the neurotoxicity of MDMA in rats. In one study, intravenous administration of alpha lipoic acid completely blocked the neurotoxic effects of MDMA. No scientific experiment has been performed to date with human subjects, although some users report that taking various combinations of antioxidants before, during, and after using MDMA serves to moderate the subsequent mood-dip and shorten the psychological recovery period.[69]

The administration of an SSRI in rats prior to the administration of MDMA has been shown to completely block neurotoxicity. This is due to the binding of such medications with SERTs. However, administering an SSRI prior to administration of MDMA also completely or partially blocks the desired effects of the latter, something a large number of users prescribed an SSRI have reported. As a compromise it has been shown that administration of an SSRI 3-4 hours after MDMA, at which time the primary effects will have tapered off significantly, markedly limits neurotoxicity overall despite some axonal damage having already occurred.[70] Several studies have administered MDMA and SSRIs to humans, including paroxetine and citalopram, and these combinations have not cause obvious increases in risk or toxicity. However, the SSRI was always given before the MDMA and potential complications may still exist.[citation needed]

Psychological

MDMA use commonly results in a rebound period of poor mood commonly known as a "comedown" (also known as a "downbuzz"), the length and severity of which depends on the user, the dose, time since previous usage, any polydrug use/abuse, and a host of other factors. It is sometimes claimed that heavy or frequent use may precipitate lasting depression and anxiety in vulnerable users, particularly those prone to depression or other mental disorders as well as anyone in a state of life crisis, although there is little published data on this.

"Redosing" in an attempt to extend MDMA's desired effects has been shown to substantially increase neurotoxicity in animals. Users also report increases in undesired physical side effects associated with MDMA use such as trisma and bruxia [citation needed]. The longer MDMA is active and being metabolized in the brain, the greater the neurotoxic damage and the greater the risk of exacerbating pre-existing emotional problems.[dubious – discuss] The more occasions MDMA is used, the greater the chances of long-term problems.[71] Deficits in memory have been shown in long term MDMA users.[72]

A recent University of Louisiana study found no significant relationship between depression and recreational ecstasy use.[73][74] The preliminary results from an ongoing Dutch study also indicates that the very moderate use of Ecstasy was not associated with depression or decreased mental state. These users also appear to be free of neurological injury of any kind.[dubious – discuss][75]

Drug interactions

Individuals who have stopped taking any type of SSRI after prolonged medication may not be able to experience the desired effects of MDMA for as long as several months following discontinuation of the medication. This is due to the fact that SSRIs decrease the brain's sensitivity to the presence of serotonin as the brain seeks to reestablish a normal neuro-electrical balance.

Most people who die while under the influence of MDMA have also consumed significant quantities of at least one other drug. The risk of MDMA-induced death overall is minimal. [76]

The use of MDMA can be dangerous when combined with other drugs (particularly monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and antiretroviral drugs, in particular ritonavir). Combining MDMA with MAOIs can precipitate hypertensive crisis, as well as serotonin syndrome which can be fatal.[77] MAO-B inhibitors such as deprenyl do not seem to carry these risks when taken at selective doses, and have been used to completely block neurotoxicity in rats. [78]

Purity

Due to its near-universal illegality, the purity of a substance sold as Ecstasy is unknown to the typical user. The MDMA content of tablets varies widely between regions and different brands of pills and fluctuates somewhat each year. Pills may contain other active substances meant to stimulate in a way similar to MDMA, such as amphetamine, methamphetamine, ephedrine, or caffeine, all of which may be comparatively cheap to produce and can help to boost profit overall. In some cases, tablets sold as Ecstasy do not even contain any MDMA. Instead they may contain an assortment of presumably undesirable drugs such as paracetamol, ibuprofen, etc.[79]

Scientific surveys of seized Ecstasy pills in the United Kingdom and Europe indicate that purity levels are generally high, and that adulterants are rare.[80] Although the US government's Office of National Drug Control Policy reports that over 55% of ecstasy pills seized in the United States in 2007 were laced with methamphetamine, it is unknown what percentage of a tablet on average the drug constitutes.[8][citation needed] It should also be noted that as a general rule, tablets seized do not necessarily represent the entire market accurately, as it is impossible to know how many of each tablet are being consumed and what each contains.

A full and proper characterization of ecstasy pills requires advanced lab techniques, such as high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (usually referred to as HPLC-MS), gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (usually referred to as GC-MS) and gas chromatography-infrared spectroscopy (usually referred to as GC-IRD). Ecstasydata.org, an American non-profit organization, uses such techniques to analyze MDMA pills for a fee.

In the Netherlands, testing of pills has been available free of charge and funded by the government at festivals and parties for almost 2 decades, but government funding has ceased in recent years, and testing of pills at festivals and parties has been banned. Testing of pills as well as other common partydrugs is still possible at several testing facilities spread throughout the country, and free of charge. Both GC/MS and HPLC/MS analysis are used to determine the active constituents of the drugs being tested, and quantative analysis is performed on some drugs including Ecstasy pills and LSD blotter paper to analyse the quantities of active consituent(s) in the pills or blotters tested. Results of the quantative analysis are given in milligrams of (each) active constituent(s) in pills, and in micrograms for the constituents of tested blotter papers. Testing results are passed on to a EU monitoring program on new drugs trends. This way early warning reports can been given when possibly dangerous adulterated substances appear on the market, like cocaine adulterated with atropine, or Ecstasy pills adulterated with or containing solely PMA. The latter has never appeared in Dutch pills but is used as an example to explain the aim of the monitoring program.

DanceSafe, among other companies, provides home testing kits to verify the contents of MDMA pills. PillReports.com and Trancesafe.com each provide the results of home testing kits in addition to the suspected contents when a test has not been performed.

PMA

There have been a number of deaths attributed to PMA, a potent and highly neurotoxic hallucinogenic amphetamine, being sold as Ecstasy. PMA is unique in its ability to quickly elevate body temperature and heart rate at relatively low doses, especially in comparison to MDMA.[81] Hence, a user who believes he is consuming two 120mg pills of MDMA could actually be consuming a dose of PMA that is potentially lethal, depending on the purity of the pill. Not only does PMA cause the release of serotonin, but also acts as an MAO-A inhibitor. When combined with an ecstasy-like substance, serotonin syndrome can result.

While both PMA and MDMA are currently Schedule I in the US, PMA was scheduled more than 10 years before MDMA.[82][83] Additionally, both drugs were rescued from obscurity by the same man, Alexander Shulgin, who at the time was synthesizing new psychoactive chemicals having been granted a license by the DEA to conduct autonomous research.

Between the late 1970s and early 1990s, virtually no PMA-related deaths were reported worldwide.[82] It was not until safrole, one of the key ingredients in the original method of MDMA synthesis, was made more difficult to acquire that PMA began to be seen in batches of ecstasy pills in any notable quantity.

PMA is almost never sought after as a drug of choice, and assuming otherwise would be impractical for several reasons. One reason is because it is so rare, another is that those who are aware of its existence are usually equally familiar with its unique hazards. The psychological effects of PMA as compared to MDMA are also quite different, making the former an unlikely substitute; PMA lacks the empathogenic qualities of MDMA, and depending on the analogue ingested, may only produce physical stimulation absent of any notable euphoria.

Heredity

In theory, a small percentage of users may be highly sensitive to MDMA; this may make first-time use especially hazardous. This includes, but is not limited to, people with congenital heart defects. Some scientists have suggested that a small percentage of people lack the proper enzymes to break down the drug. One enzyme involved in MDMA's breakdown is CYP2D6, which is deficient or totally absent in 5–10% of the Caucasian population and those of African descent, and in 1–2% of Asians.[84] However, there is no clear evidence linking lack of this enzyme to problems in users, and again the connection remains theoretical.

Poly substance use

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2008) |

Tobacco is not known for dangerous interactions with MDMA but carries its own risks, and MDMA users may be prone to overindulgence resulting in short term problems such as sore throat or coughing. Alcoholic and caffeinated beverages, which are both diuretics, can enhance the likelihood of dehydration and should be avoided.

MDMA is occasionally known for being taken in conjunction with psychedelic drugs, such as LSD or Psilocybin mushrooms. As this practice has become more prevalent, most of the more common combinations have been given nicknames. Some examples include "candy flipping", MDMA combined with LSD[85], also known as trolling (tripping and rolling), hippie flipping or flower flipping, which is MDMA combined with mushrooms,[citation needed] or triple flipping, which is MDMA with mushrooms and LSD.[citation needed] Any of these combinations has the ability to produce an extremely powerful experience and may carry an increased risk of neurotoxicity, complications and/or injury when compared to any individual substance.

Clubbers in Europe are increasingly using ketamine during or after MDMA use. Using smaller amounts while on MDMA has little pronounced effect, as the stimulation from the MDMA balances out the depressant qualities of the ketamine. This may however increase the hallucinogenic effects of the MDMA. Clubbers more often use ketamine after the primary effects of MDMA have worn off to make the comedown less dysphoric. Clubbers may also take speed during MDMA use to intensify the effects, or after MDMA use to stay awake and energised once tolerance and serotonin depletion has prevented them from gaining any more effect from MDMA. Using MDMA and amphetamine together makes both substances more neurotoxic than using them separately.[citation needed][citation needed]

Many users use mentholated products while taking MDMA, as it is believed to heighten the drug's effects. Examples include menthol cigarettes, Vicks[86] lozenges, etc. This sometimes has deleterious results on the upper respiratory tract.[87]

See also

- Retracted article on toxicity of MDMA on dopamine cells

- Psychedelic therapy

- Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies

- Rick Doblin

- Alexander Shulgin

- MDA

- MDEA

- MDMC (Methylone)

- PMA

- Amphetamine

- Leah Betts & Anna Wood (Deaths attributed to hyponatermia)

- RAVE Act

- Ecstasy Rising, (2004 ABC television documentary hosted by Peter Jennings)

References

- ^ Stimulants, narcotics, hallucinogens - Drugs, Pregnancy, and Lactation, Gerald G. Briggs, OB/GYN News, June 1, 2003.

- ^ http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec15/ch198/ch198k.html?qt=amphetamine&alt=sh

- ^ http://www.nlm.nih.gov/cgi/mesh/2008/MB_cgi?mode=&term=Phenethylamines&field=entry

- ^ "Where is Ecstacy Legal?"

- ^ The pharmacology and clinical pharmacology of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, "ecstasy") [1]

- ^ The neuropsychology of ecstasy (MDMA) use: a quantitative review.

- ^ McCann & Ricaurte (2001) 'Caveat Emptor: Editors Beware' Neuropsychopharmacology 24,3:333-4 http://www.maps.org/w3pb/new/2001/2001_mccann_1129_1.pdf

- ^ Gijsman et al. (1999) 'MDMA study' Neuropsychopharmacology 21,4:597 http://www.maps.org/w3pb/new/1999/1999_gijsman_295_1.pdf

- ^ Kish (2002) 'How strong is the evidence that brain serotonin neurons are damaged in human users of ecstasy?' Pharmacol Biochem Behav 71,4:845–855 http://www.maps.org/w3pb/new/2003/2003_kish_6239_1.pdf

- ^ Aghajanian & Liebermann (2001) 'Caveat Emptor: Reseearchers Beware' Neuropsychopharmacology 24,3:335-6 http://www.maps.org/w3pb/new/2001/2001_aghajanian_1130_1.pdf

- ^ MAPS: Psychedelic Research Worldwide

- ^ Bernschneider-Reif S, Oxler F, Freudenmann RW. The origin of MDMA ("ecstasy")--separating the facts from the myth. Pharmazie. 2006;61:966-72.

- ^ Saunders, Nicholas. Ecstasy Reconsidered (1997), page 7.

- ^ http://www.erowid.org/chemicals/mdma/mdma_info6.shtml

- ^ Tom Shroder, "The Peace Drug", Washington Post Magazine, November 25, 2007

- ^ Bibliography of psychadelic research studies collected by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies

- ^ The Austin Chronicle - "Countdown to Ecstasy" by Marc Savlov

- ^ "Pharmaceutical company unravels drug's chequered past" (HTML). 2005. Retrieved 18 August.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Erowid MDMA Vault : Info #3 on scheduling

- ^ Primetime with Peter Jennings

- ^ "This is your brain". TheDEA.

- ^ "Ecstasy really does unleash the love hormone". New Scientist. April 4, 2007.

- ^ Parrott AC, Lasky J (1998). "Ecstasy (MDMA) effects upon mood and cognition: before, during and after a Saturday night dance". Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 139 (3): 261–8. PMID 9784083.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Verheyden SL, Henry JA, Curran HV (2003). "Acute, sub-acute and long-term subjective consequences of 'ecstasy' (MDMA) consumption in 430 regular users". Hum Psychopharmacol. 18 (7): 507–17. doi:10.1002/hup.529. PMID 14533132.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Verheyden SL, Maidment R, Curran HV (2003). "Quitting ecstasy: an investigation of why people stop taking the drug and their subsequent mental health". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford). 17 (4): 371–8. PMID 14870948.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rodgers J, Buchanan T, Scholey AB, Heffernan TM, Ling J, Parrott AC (2003). "Patterns of drug use and the influence of gender on self-reports of memory ability in ecstasy users: a web-based study". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford). 17 (4): 389–96. PMID 14870950.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jones and Simpson (1999) "Mechanisms and management of hepatotoxicity in ecstasy (MDMA) and amphetamine intoxications" Aliment Pharmacol Ther 13,2:129-33

- ^ Milosevic et al. (1999) "The occurrence of toothwear in users of Ecstasy (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine) Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 27,4:283-7

- ^ [http://www.maps.org/w3pb/new/1991/1991_creighton_526_1.pdf Creighton et al. 1991 ‘Ecstasy’ psychosis and flashbacks. Br. J. Psychiatry 159, 713�/715.]

- ^ Peter Jennings "Ecstasy Rising." ABC. Apr 1, 2004.

- ^ McCann et al. (1998). Positron emission tomographic evidence of toxic effect of MDMA ("Ecstasy") on brain serotonin neurons in human beings. The Lancet, 352, 9138

- ^ Kish,S. J. (2002) How strong is the evidence that brain serotonin neurons are damaged in human users of ecstasy? Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, 71, 845 – 855

- ^ Ricaurte et al. (2002). Severe Dopaminergic Neurotoxicity in Primates After a Common Recreational Dose Regimen of MDMA ("Ecstasy"). Science, 297, 5590, 2260 - 2263

- ^ Ricaurte et al. (2003). Retraction of Ricaurte et al., Science 297 (5590) 2260-2263. Science, 301, 5639, 1479

- ^ Doblin, R. Clarification of Information Presented on MTV's Special on Ecstasy. MAPS

- ^ Win et al. (2006). A Prospective Cohort Study on Sustained Effects of Low-Dose Ecstasy Use on the Brain in New Ecstasy Users. Neuropsychopharmacology, 1-13

- ^ DEA, Drug Information, MDMA

- ^ Johnston, L. D., O'Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2007, December 11). National press release, "Overall, illicit drug use by American teens continues gradual decline in 2007." University of Michigan News Service, Ann Arbor, 57 pp.

- ^ Saunders, Nicholas. Ecstatsy and the Dance Culture (1995), page 168

- ^ Saunders, Nicholas. Ecstasy Reconsidered (1997), page 237

- ^ Home Office Research Study 227 Middle market drug distribution, page 22

- ^ London: The highs and the lows 2—A report from the Greater London Alcohol and Drug Alliance. City Hall, London: Greater London Authority. 2007. ISBN 1-85261-974-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/health/article3850302.ece

- ^ Doblin, R. ( 2002) A clinical plan for MDMA (ecstasy) in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Partnering with the FDA. J. Psychoactive Drugs, 35, 185–194.

- ^ Greer, G.; Tolbert, R. (1986). "Subjective Reports of the Effects of MDMA in a Clinical Setting" (reprint). Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 18 (4): 319–327.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Greer, G.; Tolbert, R. (1998). "A Method of Conducting Therapeutic Sessions with MDMA" (reprint). Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 30 (4): 371–379.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dyck, E. (2005) Flashback: Psychiatric Experimentation With LSD in Historical Perspective. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 50, 381-387.

- ^ Sessa, B., & Nutt, D. (2007) MDMA, politics and medical research: Have we thrown the baby out with the bathwater? Journal of Psychopharmacology, 21, 787-791.

- ^ Halpern, J. H. (2006) Update on the MDMA-assisted Psychotherapy Study for Treatment-Resistant Anxiety Disorders Secondary to Advanced Stage Cancer. MAPS, 17, 16.

- ^ Shroder, T. (November 25, 2007). "The Peace Drug". Washington Post. p. W12.

- ^ Parrott, A. C. (2006, June) The psychotherapeutic potential of MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine): an evidence-based review. Psychopharmacology, 191, 181-193.

- ^ Nov 05 DEA Microgram newsletter

- ^ MAPS. "Documents from the DEA Scheduling Hearing of MDMA,".

- ^ E for Ecstasy by Nicholas Saunders, Appendix 1: Reference Section

- ^ Nimmo S M, Kennedy B W, Tullett W M, Blyth A S, Dougall J R (1993) Drug-induced hyperthermia. Anaesthesia 48: 892–895

- ^ Malberg J E, Seiden L S (1998) Small changes in ambient temperature causes large changes in 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-induced serotonin neurotoxicity and core body temperature in the rat. J. Neuroscience 18: 5086–5094

- ^ Wolff K, Tsapakis E M, Winstock A R, Hartley D, Holt D, Forsling M L, Aitchison K J(2006) Vasopressin and oxytocin secretion in response to the consumption of ecstasy in a clubbing population. Journal of Psychopharmacology 20(3): 400–410

- ^ Fischer, C. and Hatzidimitriou, G. and Wlos, J. and Katz, J. and Ricaurte, G. (1995). "Reorganization of ascending 5-HT axon projections in animals previously exposed to the recreational drug (+/-) 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA," ecstasy")". Journal of Neuroscience. Soc Neuroscience.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Scheffel U, Szabo Z, Mathews WB, Finley PA, Dannals RF, Ravert HT, Szabo K, Yuan J, Ricaurte GA. “In vivo detection of short- and long-term MDMA neurotoxicity--a positron emission tomography study in the living baboon brain”. Synapse. 1998;29(2):183-92. Abstract

- ^ Reneman L, Lavalaye J, Schmand B, de Wolff FA, van den Brink W, den Heeten GJ, Booij J. “Cortical Serotonin Transporter Density and Verbal Memory in Individuals Who Stopped Using 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or 'Ecstasy'): Preliminary Findings”. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(10):901-906. Abstract

- ^ "p-Chlorophenylalanine Changes Serotonin Transporter mRNA Levels and Expression of the Gene Product", Journal of Neurochemistry, 1996. Online copy (pdf)

- ^ Neurotoxicity, at TheDEA.org

- ^ Down-regulation of Receptors: The most probable cause of ecstasy-related depression at DanceSafe.org

- ^ Neurotoxicity at Dancesafe.org

- ^ Does MDMA Cause Brain Damage?, Matthew Baggott, and John Mendelson

- ^ Research on Ecstasy Is Clouded by Errors, Donald G. McNeil Jr., New York Times, December 2, 2003.

- ^ Cortical Serotonin Transporter Density and Verbal Memory in Individuals Who Stopped Using 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or 'Ecstasy'): Preliminary Findings, Reneman L, Lavalaye J, Schmand B, de Wolff FA, van den Brink W, den Heeten GJ, Booij J. Archives of General Psychiatry 2001;58(10):901-906.

- ^ Ecstasy Study Botched, Retracted, Kristen Philipkoski, Wired.com, 09.05.03

- ^ Do Antioxidants Protect Against MDMA Hangover, Tolerance, and Neurotoxicity?, Earth Erowid, Dec 2001.

- ^ The Prozac Misunderstanding at TheDEA.org

- ^ Depression at DanceSafe.org

- ^ Wareing, M. and Fisk, J.E. and Murphy, P.N. (2000). "Working memory deficits in current and previous users of MDMA ('ecstasy')" (PDF). Br J Psychol. pp. 181--8.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Study claims recreational ecstasy use and depression unrelated, Wikinews, April 26, 2006]

- ^ Recreational Ecstacy Use and Depression, Journal of Psychopharmacology, Vol. 20, No. 3, 411-416 (2006) DOI: 10.1177/0269881106063265

- ^ A Prospective Cohort Study on Sustained Effects of Low-Dose Ecstasy Use on the Brain in New Ecstasy Users

- ^ Primetime video

- ^ Death following ingestion of MDMA (ecstasy) and moclobemide, Vuori et al. Addiction 2003 Mar;98(3):365-368

- ^ The Prozac Misunderstanding, at TheDEA.org

- ^ Summary Statistics for EcstasyData.org Lab Testing Results

- ^ "Is ecstasy MDMA? A Review of the proportion of ecstasy tablets containing MDMA, their dosage levels, and the changing perceptions of purity", AC Parrott, Psychopharmacology, March 2004: "The latest reports suggest that non-MDMA tablets are now infrequent, with purity levels between 90% and 100%."

- ^ Club Drug Update, Jeff Morelock, PRP Online, Spring 2003

- ^ a b PMA Timeline at Erowid

- ^ MDMA Timeline at Erowid

- ^ eMedicine - Toxicity, MDMA : Article by David Yew

- ^ UMD Center for Substance Abuse Research. "Ecstasy:CESAR".

- ^ "Director's Report to the National Advisory Council on Drug Abuse".

- ^ Erowid Experience Vaults: Vicks used with Ecstasy - Important Warning About Vicks on Ecstasy - 4287

Further reading

- Adam, David. Truth about ecstasy's unlikely trip from lab to dance floor: Pharmaceutical company unravels drug's chequered past, Guardian Unlimited, .

- Baggott, Matthew, and John Mendelson. “MDMA Neurotoxicity”. Ecstasy: The Complete Guide. Ed. Julie Holland. Spring 2001 from www.erowid.com.

- de la Torre, Rafael et al. (2000), Non-linear pharmacokinetics of MDMA (`ecstasy') in humans. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 2000; 49(2):104-9

- de la Torre, Rafael & Farré, Magí (2004). Neurotoxicity of MDMA (ecstasy): the limitations of scaling from animals to humans. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 25, 505-508.

- Eisner, Bruce. Ecstasy: The MDMA Story, 2nd ed. Berkeley, CA: Ronin Publishing, 1994.

- Erowid, Earth. “Do Antioxidants Protect Against MDMA Hangover, Tolerance, and Neurotoxicity?” Erowid Extracts. December 2001; 2:6-11.

- Jones, Douglas C. et al. (2004). Thioether Metabolites of 3,4-Methylenedioxyamphetamine and 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine Inhibit Human Serotonin Transporter (hSERT) Function and Simultaneously Stimulate Dopamine Uptake into hSERT-Expressing SK-N-MC Cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 311, 298-306.

- Kalant H. (2001) The pharmacology and toxicology of "ecstasy" (MDMA) and related drugs. CMAJ. October 2;165(7):917-28. Review. PMID Full Text

- Miller, R.T. et al. (1997). 2,5-Bis-(glutathione-S-yl)-alpha-methyldopamine, a putative metabolite of (+/-)-3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine, decreases brain serotonin concentrations. Eur J Pharmaco. 323(2-3), 173-80. Abstract retrieved April 17, 2005, from PubMed.

- Monks, T.J. et al. (2004). The role of metabolism in 3,4-(+)-methylenedioxyamphetamine and 3,4-(+)-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (ecstasy) toxicity. Ther Drug Monit 26(2), 132-136.

- Morgan, Michael John (2000). Ecstasy (MDMA): a review of its possible persistent psychological effects. Psychopharmacology 152, 230-248.

- Shankaran, Mahalakshmi, Bryan K. Yamamoto, and Gary A. Gudelsky. “Ascorbic Acid Prevents 3,4,-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)- Induced Hydroxyl Radical Formation and the Behavioral and Neurochemical Consequences of the Depletion of Brain 5-HT”. Synapse. 2001; 40:55-64.

- Strote, Jared et al. (2002). Increasing MDMA use among college students: results of a national survey. Journal of Adolescent Health 30, 64-72.

- Sumnall, Harry R. & Cole, Jon C. (2005). Self-reported depressive symptomatology in community samples of polysubstance misusers who report Ecstasy use: a meta-analysis. Journal of Psychopharmacology 19(1), 84-92.

- Vollmer, Grit. "Crossing the Barrier." Scientific American Mind. June/July 2006, 34-39.

- Yeh, S. Y. “Effects of Salicylate on 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-Induced Neurotoxicity in Rats”. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1997; Vol. 58, No. 3: 701-708.

- Gerra G, Zaimovic A, Ampollini R, Giusti F, Delsignore R, Raggi MA, Laviola G, Macchia T, Brambilla F. "Experimentally induced aggressive behavior in subjects with 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine ("Ecstasy") use history: psychobiological correlates." J Subst Abuse. 2001;13(4):471-91

- Reid LW, Elifson KW, Sterk CE. "Hug drug or thug drug? Ecstasy use and aggressive behavior". Violence Vict. 2007;22(1):104-19.

- Ksir, Charles, Carl L. Hart, and Oakley Ray. Drugs, Society and Human Behavior, 12th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill, 2006.

External links

- Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies MDMA Resarch Page - A regularly updated information source about MAPS' efforts to develop MDMA into an FDA-approved prescription medicine.

- MDMA PiHKAL entry

- Jennings, Peter. "Primetime Special: Peter Jennings — Ecstasy Rising." ABC News, April 1, 2004.

- EcstasyData.org A database of photos and lab-test results of over 1500 pills of "Ecstasy."

- American Council for Drug Education factsheet on Ecstasy