Newt Gingrich: Difference between revisions

→Personal life: rm uncited + analysis |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 244: | Line 244: | ||

[[Category:American political writers]] |

[[Category:American political writers]] |

||

[[Category:Baptists from the United States]] |

[[Category:Baptists from the United States]] |

||

[[Category:Bohos]] |

|||

[[Category:Clinton Administration]] |

[[Category:Clinton Administration]] |

||

[[Category:Congressional scandals]] |

[[Category:Congressional scandals]] |

||

Revision as of 07:13, 6 March 2008

This article needs to be updated. |

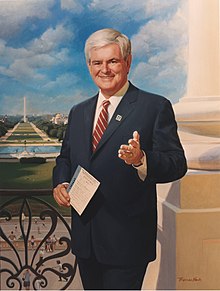

Newt Gingrich | |

|---|---|

| File:NewtGingrich2.jpg | |

| 58th Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives | |

| In office January 4, 1995 – January 3, 1999 | |

| Preceded by | Tom Foley |

| Succeeded by | Dennis Hastert |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Georgia's 6th district | |

| In office January 3, 1979 – January 3, 1999 | |

| Preceded by | Jack Flynt |

| Succeeded by | Johnny Isakson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | thumb right |

| Died | thumb right |

| Resting place | thumb right |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouses | Jackie Battley (1962-1977) Marianne Ginther (1981-1999) Callista Bisek (2000-current) |

| Parent |

|

| Alma mater | Emory University Tulane University |

| Signature | File:GingrichSig.gif |

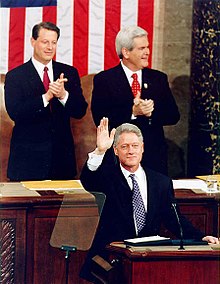

Newton Leroy Gingrich, (born June 17, 1943), served as the Speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1995 to 1999. In 1995, Time magazine selected him as the Person of the Year for his role in leading the Republican Revolution in the House, ending 40 years of Democratic Party majorities in that body. During his tenure as Speaker he represented the public face of the Republican opposition to Bill Clinton.

A college history professor, conservative political leader, and prolific author, Gingrich twice ran unsuccessfully for the House before first winning a seat in November 1978. He was re-elected 10 times, and his activism as a member of the House's Republican minority eventually enabled him to succeed Dick Cheney as House Minority Whip in 1989. As a co-author of the 1994 Contract with America, Gingrich was in the forefront of the Republican Party's dramatic success in the 1994 Congressional elections and subsequently was elected Speaker. Gingrich's leadership in Congress was marked by opposition to many of the policies of the Clinton Administration, culminating in the impeachment of President Clinton. Shortly after the 1998 elections, where Republicans lost 5 seats in the House, Gingrich announced his resignation as Speaker.

After resigning his seat, Gingrich has maintained a career as a political analyst and consultant and continues to write works related to government and other subjects, such as historical fiction.

Early life and education

Newt Gingrich was born Newton Leroy McPherson on June 17, 1943 in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, to nineteen-year-old Newton Searles McPherson and sixteen-year-old Kathleen Daugherty, who were married in September 1942.[1][2] His mother raised him by herself until she married Robert Gingrich, who then adopted Newt. Gingrich has a younger half-sister, Candace Gingrich, a gay and lesbian rights activist who was born when Newt was already a young adult.

Gingrich was the child of a career military family, moving a number of times while growing up and attending school at various military installations. He ultimately graduated from Baker High School in Columbus, Georgia in 1961. He received a B.A. degree from Emory University in Atlanta in 1965. He received an M.A. in 1968 and a Ph.D in 1971 in Modern European History from Tulane University in New Orleans.

Gingrich taught history at University of West Georgia in Carrollton, Georgia from 1970 to 1978, although he was untenured.[3] Newt also taught a class, Renewing American Civilization, at Kennesaw State University in 1993.[4]

Personal life

Newt Gingrich has been married three times. He married Jackie Battley, his former high school geometry teacher, when he was 19 years old (she was seven years his senior at 26 years old).[5][6] After an alleged affair with Ann Manning in 1977, Gingrich sought a divorce from Battley.[7] In 1981, Gingrich wed Marianne Ginther,[8] to whom he remained married until 1999, the same year Gingrich had an affair with a then 33-year-old Congressional staffer, Callista Bisek. He and Bisek were married in 2000 and currently reside in Virginia. Gingrich has two daughters, Kathy and Jackie from his marriage to Jackie Battley, two sons-in-law and two grandchildren.[9]

Although college peers noted Gingrich's preference to discuss politics more than his personal life,[10] Gingrich’s personal life has been the subject of much attention from both the media and his political opponents over the years. In 1992, his Democratic opponent, Tony Center, ran an ad claiming that Gingrich had "delivered divorce papers to his wife the day after her cancer operation," which was not strictly true, although friends have acknowledged that he discussed divorce terms with his estranged wife while visiting her in the hospital.[11]

Positions

Illegal immigration

From Gingrich's five challenges: "No serious nation in the age of terror can afford to have wide-open borders with millions of illegal aliens crossing at will."

Although a source of friction in the conservative wing of the GOP (and some pro-union "blue dog" democrats), Gingrich supports a "guest worker program" for Mexican citizens, meaning that an undetermined number of Mexican citizens would be allowed to come to the United States and work for a period of time, then return to Mexico. Gingrich also supports the idea of allowing some of these guest workers to become citizens. In his book Winning the Future, he says:

"Along with total border control, we must make it easier for people who enter the United States legally, to work for a set period of time, obey the law, and return home. The requirements for participation in a worker visa program should be tough and uncompromising. The first is essential: Everyone currently working in the United States illegal must return to their home country to apply for the worker visa program. Anything less than requiring those who are here illegally to return home to apply for legal status is amnesty, plain and simple."

Global warming

In April 2007, Gingrich held an open debate on climate change with Senator John Kerry. In this debate, he stated that he believes that global warming is indeed an occurring phenomenon: "My message, I think, is that the evidence is sufficient that we should move toward the most effective possible steps to reduce carbon loading in the atmosphere." Gingrich's environmental ideas were revealed in his book, A Contract with the Earth. Gingrich supports tax breaks to mitigate carbon emissions instead of regulations such as cap-and-trade.[12]

United States Representative

Early elections

In 1974 and 1976, Gingrich made two unsuccessful runs for Congress in Georgia's sixth congressional district, which stretched from the southern Atlanta suburbs to the Alabama border. Gingrich lost both times to incumbent Democrat Jack Flynt. Flynt was a conservative Democrat who had served in Congress since 1955 and never faced a serious challenge prior to Gingrich's two runs against him. However, Gingrich nearly defeated Flynt in 1974, a year that was otherwise a very bad year for Republicans due to Watergate. A 1976 rematch was similarly close, despite the presence of favorite son Jimmy Carter on the presidential ballot.

Flynt chose not to run for re-election in 1978, and the Democrats fielded state senator Virginia Shapard in his place. Shapard's support of the Equal Rights Amendment [1] backfired against her in the socially conservative district, and Gingrich defeated her by almost 9 points.

Gingrich was reelected six times from this district, facing only one truly difficult race. In the House elections of 1990, he defeated Democrat David Worley by only 974 votes. [2]

Pre-speakership congressional activities

In 1981, Gingrich co-founded the Congressional Military Reform Caucus (MRC) as well as the Congressional Aviation and Space Caucus. In 1983 he founded the Conservative Opportunity Society, a group that included young conservative House Republicans. In 1983, Gingrich demanded the expulsion of fellow representatives Dan Crane and Gerry Studds for their roles in the Congressional Page sex scandal.

In May 1988, Gingrich (along with 77 other House members and Common Cause) brought ethics charges against Democratic Speaker Jim Wright, who was alleged to have used a book deal to circumvent campaign-finance laws and House ethics rules and eventually resigned as a result of the inquiry. Gingrich's success in forcing Wright's resignation was in part responsible for his rising influence in the Republican caucus.[citation needed] In 1989, after House Minority Whip Dick Cheney was appointed Secretary of Defense, Gingrich was elected to succeed him. Gingrich and others in the house, especially the newly minted Gang of Seven, railed against what they saw as ethical lapses in the House, an institution that had been under Democratic control for almost 40 years. The House banking scandal and Congressional Post Office Scandal were emblems of the corruption exposed.

Election of 1992

During the 1990s round of redistricting, Georgia picked up an additional seat as a result of the 1990 United States Census. However, the Democratic-controlled General Assembly split Gingrich's old territory among three other districts. Gingrich's home in Carrollton was drawn into the Columbus-based 3rd District, represented by five-term Democrat Richard Ray.

At the same time, they created a new 6th District in Fulton and Cobb counties in the wealthy northern suburbs of Atlanta — an area Gingrich had never represented. However, Gingrich sold his home in Carrollton, moved to Marietta in the new 6th and won a very close Republican primary. The primary victory was tantamount to election in the new, heavily Republican district. Also, Ray narrowly lost to Republican state senator Mac Collins.

Speaker of the House

The Contract with America and rise to Speaker

In the 1994 campaign season, in an effort to offer a concrete alternative to shifting Democratic policies and to unite distant wings of the Republican Party, Gingrich presented Dick Armey's and his Contract with America. The contract was signed by himself and other Republican candidates for the House of Representatives. The contract ranged from issues with broad popular support, including welfare reform, term limits, tougher crime laws, and a balanced budget law, to more specialized legislation such as restrictions on American military participation in U.N. missions. In the November 1994 elections, Republicans gained 54 seats and took control of the House for the first time since 1954.

Longtime House Minority Leader Bob Michel of Illinois had not run for re-election in 1994, giving Gingrich, as the highest-ranking Republican returning to Congress, the inside track to becoming Speaker. Legislation proposed by the 104th United States Congress included term limits for Congressional Representatives, tax cuts, welfare reform, and a balanced budget amendment, as well as independent auditing of the finances of the House of Representatives and elimination of non-essential services such as the House barbershop and shoe-shine concessions. Congress fulfilled Gingrich's Contract promise to bring all ten of the Contract's issues to a vote within the first 100 days of the session, even though most legislation was held up in the Senate, vetoed by President Bill Clinton, or substantially altered in negotiations with Clinton. The Contract was criticized by the Sierra Club and by Mother Jones magazine as a Trojan horse tactic that, while deploying the rhetoric of reform, would have the real effect of allowing corporate polluters to profit at the expense of the environment;[13] It was referred to by opponents, including President Clinton, as the "Contract on America".[14]

However, most parts of the Contract eventually became law in some fashion and represented a dramatic departure from the legislative goals and priorities of previous Congresses. See Implementation of the Contract for a detailed discussion of what was and was not enacted.

Government shutdown and the "snub"

The momentum of the Republican Revolution stalled in late 1995 and early 1996 as a result of a budget fight between Congressional Republicans and President Bill Clinton. Speaker Gingrich and the new Republican majority wanted deep cuts to government spending, which Clinton flatly rejected. Without enough votes to override President Clinton's veto, Gingrich led the Republicans not to submit a revised budget, allowing the previously approved appropriations to expire on schedule, and causing parts of the Federal government to shut down for lack of funds.

Gingrich inflicted a temporary blow to his public image by seeming to suggest that the Republican hard-line stance over the budget was in part due to his feeling "snubbed" by the President the day before following his return from Yitzhak Rabin's funeral in Israel. Gingrich was lampooned in the media as a petulant figure with an inflated self-image,[citation needed] and at least one editorial cartoon depicted him as having thrown a temper tantrum.[15] Democratic leaders took the opportunity to attack Gingrich's motives for the budget standoff, and some say the shutdown might have contributed to Clinton's re-election in November 1996.[16][17]

Tom DeLay recounts the event in his book, No Retreat, No Surrender, that Gingrich "made the mistake of his life" and says the following of Gingrich's mis-step of the shutdown:[18]

"He told a room full of reporters that he forced the shutdown because Clinton had rudely made him and Bob Dole sit at the back of Air Force One...Newt had been careless to say such a thing, and now the whole moral tone of the shutdown had been lost. What had been a noble battle for fiscal sanity began to look like the tirade of a spoiled child..The revolution, I can tell you, was never the same."

In her autobiography, Living History Hillary Rodham Clinton shows a picture of Bill Clinton, Dole, and Gingrich laughing on the plane, disproving the "snub".

Ethics sanctions

Eighty-four ethics charges were filed against Speaker Gingrich during his term, including claiming tax-exempt status for a college course run for political purposes. Following an investigation by the House Ethics Committee, Gingrich was sanctioned for US$300,000[19] after the House Ethics Committee concluded that inaccurate information supplied to investigators represented "intentional or ... reckless" disregard of House rules.[20] Special Counsel James M. Cole concluded that Gingrich violated federal tax law and had lied to the ethics panel in an effort to force the committee to dismiss the complaint against him. However, the full panel refused to reach a conclusion about whether Gingrich had violated federal tax law and instead decided to leave that finding up to the IRS.[21] In 1999, the IRS cleared the organizations connected with the "Renewing American Civilization" courses under investigation for possible tax violations, which suggests that Gingrich did not use tax-exempt money for political purposes.[22]

Leadership challenge

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2007) |

In the summer of 1997, a few House Republicans had come to see Gingrich's public image as a liability and attempted to replace him as Speaker. According to Time, the conspiracy was engineered by several Republican backbenchers, including Steve Largent of Oklahoma, Lindsey Graham of South Carolina and Mark Souder of Indiana. They soon gained the support of the four Republicans who ranked directly below Gingrich in the House leadership — Armey, House Majority Whip Tom DeLay, Republican conference chairman John Boehner of Ohio, and Republican leadership chairman Bill Paxon of New York.

On July 9, DeLay, Boehner and Paxon had the first of several secret meetings to discuss the rebellion. The next night, DeLay met with 20 of the plotters in Largent's office, and appeared to assure them that the leadership was with them.

Under the plan, Armey, DeLay, Boehner and Paxon were to present Gingrich with an ultimatum — resign or be voted out. Combined with the votes of the Democrats, there appeared to be enough votes to vacate the chair. However, the rebels decided that they wanted Paxon to be the new Speaker. At that point, Armey backed out, and told his chief of staff to warn Gingrich about the coup.

In response, Gingrich forced Paxon to resign his post, but backed off initial plans to force a vote of confidence in the rest of the Republican leadership.[23]

Fall from speakership, resignation from the House

By 1998, Gingrich had become a highly visible and polarizing figure in the public's eye, making him an easy target for Democratic congressional candidates across the nation. In 1997 a strong majority of Americans believed Gingrich should have been replaced as Speaker of the House, and he held an all-time low job approval rating of 28%.[24] During this period, Gingrich focused on the perjury charges against Clinton as a unifying campaign theme in national Republican advertising. While Republicans believed this theme would ensure gains in the 1998 midterm elections, they instead lost five seats in the House — the worst performance in 64 years for a party that didn't hold the presidency.

Gingrich suffered much of the blame for the election loss. Facing another rebellion in the Republican caucus, he announced on November 6 that he would not only stand down as Speaker, but would leave the House as well. He had been handily reelected to an 11th term in that election, but declined to take his seat. According to Newsweek, he had lost control over his caucus long before the election, and it was possible that he would not have been reelected as Speaker in any case.[25]

Post-congressional life

Gingrich has since remained involved in national politics and public policy debate. He is a senior fellow at the conservative think tank American Enterprise Institute, focusing on health care (he has founded the Center for Health Transformation), information technology, the military, and politics. Gingrich is also a Distinguished Visiting Fellow at the conservation think tank Hoover Institute, focusing on U.S. politics, world history, national security policy, and environmental policy issues. He sometimes serves as a commentator, guest or panel member on television news shows, mostly on the Fox News Channel. He is listed as a contributor by Fox News Channel, and frequently appears as a guest on the channel; he has also hosted occasional specials for the Fox News Channel.

In June 2006, Gingrich publicly called for Congressman Jack Murtha to be censured by the United States Congress for what Gingrich claims was Murtha's statement that America was a greater threat to world stability than Iran or North Korea. The paper that originally printed the statement has recently backed away and admitted that Murtha had been misquoted and was merely citing a poll that showed the world believed the United States was a greater threat than either of those nations. Gingrich, however, has refused to apologize or retract his call for Murtha to be censured.

Besides politics Gingrich has written a book, Rediscovering God in America. Since Gingrich has, "dedicated much of his time to calling America back to our Christian heritage", Jerry Falwell invited him to be the speaker, for the second time, at Liberty University's graduation, May 19, 2007.[26]

Alternate history collaboration with William R. Forstchen

In 1995, Gingrich collaborated with William R. Forstchen on the alternate history novel 1945, describing a World War II in which the US fought against (and defeated) Japan only, while Nazi Germany defeated the Soviet Union, and the two confront each other in a cold war that swiftly turns hot.

Some years later, Gingrich and Forstchen turned to co-authoring an alternate history trilogy of the American Civil War, in which the Confederacy wins the battle of Gettysburg. The trilogy consists of Gettysburg (2003), Grant Comes East (2004), and Never Call Retreat (2005).

In 2007 they published Pearl Harbor: A Novel of December 8th, the first of a new series.

Possible 2008 presidential run

Between 2005 and 2007, Gingrich expressed interest in being a candidate for the 2008 Republican nomination for the Presidency.[27][28][29][30] On September 28, 2007, Gingrich announced that if his supporters pledged $30 million to his campaign (until October 21), he would compete for the nomination.[31]

However, on September 29 spokesman Rick Tyler said that Gingrich would not seek the presidency in 2008 because he could not continue to serve as chairman of American Solutions. "It is legally impermissible for him to continue on as chairman of American Solutions (for Winning the Future) and to explore a campaign for president," Tyler said.[32]

Books authored

Nonfiction

- The Government's Role in Solving Societal Problems. Associated Faculty Press, Incorporated. January 1982 ISBN 0-86733-026-0

- Window of Opportunity. Tom Doherty Associates, December 1985. ISBN 0-312-93923-X

- Contract with America (co-editor). Times Books, December 1994. ISBN 0-8129-2586-6

- Restoring the Dream. Times Books, May 1995. ISBN 0-8129-2666-8

- Quotations from Speaker Newt. Workman Publishing Company, Inc., July 1995. ISBN 0-7611-0092-X

- To Renew America. Farrar Straus & Giroux, July 1996. ISBN 0-06-109539-7

- Lessons Learned The Hard Way. HarperCollins Publishers, May 1998 ISBN 0-06-019106-6

- Presidential Determination Regarding Certification of the Thirty-Two Major Illicit Narcotics Producing and Transit Countries. DIANE Publishing Company, September 1999. ISBN 0-7881-3186-9

- Saving Lives and Saving Money. Alexis de Tocqueville Institution, April 2003. ISBN 0-9705485-4-0

- Winning the Future. Regnery Publishing, January 2005. ISBN 0-89526-042-5

- Rediscovering God in America: Reflections on the Role of Faith in Our Nation's History and Future. Integrity Publishers, October 2006. ISBN 1-59145-482-4

- "A Contract with the Earth," (Newt on the environment) Johns Hopkins Press, October 1, 2007.

- Real Change: From the World That Fails to the World That Works. Regnery Publishing, January 2008. ISBN 978-1596980532

Alternate History

Alternate history is a subgenre of speculative fiction that is set in a world in which history has diverged from history as it is generally known. Gingrich co-wrote the following alternate history novels and series of novels with William R. Forstchen.

- 1945 Baen Books, August 1995 ISBN 978-0671877392

Civil War Series

- Gettysburg: A Novel of the Civil War Thomas Dunne Books, June 2003 ISBN 978-0312309350

- Grant Comes East Thomas Dunne Books, June 2004 ISBN 0-312-30937-6

- Never Call Retreat: Lee and Grant: The Final Victory Thomas Dunne Books, June 2005 ISBN 0-312-34298-5

Pacific War Series

- Pearl Harbor: A Novel of December 8th Thomas Dunne Books, May 2007 ISBN 0-312-36350-8

References

- ^ "The Long March of Newt Gingrich". PBS Frontline. 1996-01-16. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "Biography of Newton Gingrich". U.S. Congressional Library. 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- ^ Lemann, Nicholas (1996-02-26). "America's New Class System". CNN/Time. Retrieved 2006-08-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Scott, Thomas (2007-02-21). "Kennesaw State University". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2007-05-21.

- ^ Russakoff, Dale (December 18, 1994), "He Knew What He Wanted; Gingrich Turned Disparate Lessons Into a Single-Minded Goal Series: MR. SPEAKER: THE RISE OF NEWT GINGRICH Series Number: 1/4;", Washington Post, pp. A1

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Cox, Major W. (1995-01-04). "Gingrich May Be Perfect for the Task". Montgomery Advertiser. Retrieved 2007-03-09.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Talbot (1998-08-28). first=Stephen "Newt's glass house". Salon. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Missing pipe in:|url=(help) - ^ "Good Newt, Bad Newt". Vanity Fair (via PBS).

- ^ "?".

- ^ "?".

- ^ Evans, Ben (2007-03-08). "Gingrich had an Affair during Clinton probe". AP. Retrieved 2007-03-08.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Quaid, Libby. Kerry, Gingrich Debate Global Warming, The Associated Press, April 10, 2007

- ^ "Contract on America's Environment". The Planet Newsletter. Sierra Club. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

- ^ http://www.asne.org/kiosk/archive/convention/2000/clinton.htm

- ^ http://z.about.com/d/politicalhumor/1/0/_/7/newt_baby.jpg

- ^ Hollman, Kwame (1996-11-20). PBS.org "The State of Newt". PBS. Retrieved 2006-08-14.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Murdock, Deroy (2000-08-28). NationalReview.com "Newt Gingrich's Implosion". National Review. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ DeLay, Tom. No Retreat, No Surrender: One American's Fight. p. 112.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/govt/leadership/stories/012297.htm

- ^ Yang, John E. and Dewar, Helen (1997-01-18). washingtonpost.com "Ethics Panel Supports Reprimand of Gingrich". Washington Post. p. A01. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/govt/leadership/stories/011897.htm

- ^ http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9A0DE7D61138F937A35751C0A96F958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=1

- ^ http://www.cnn.com/ALLPOLITICS/1997/07/21/time/gingrich.html

- ^ Holland, Keating (1997-04-18). "Poll: Majority Says Gingrich Loan 'Inappropriate'". CNN. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/15674090/site/newsweek/

- ^ Why I Asked Newt Gingrich to Speak at Liberty's Graduation. NewsMax.com, March 9, 2007.

- ^ Eilperin, Juliet (2006-06-10). "Gingrich May Run in 2008 if No Frontrunner Emerges". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2006-08-25.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ On 13 October 2005, Gingrich suggested he was considering a run for president, saying "There are circumstances where I will run", elaborating that those circumstances would be if no other candidate champions some of the platform ideas advocated by Gingrich. http://www.newt.org/backpage.asp?art=3573

- ^ On May 14, 2007, Gingrich stated on Good Morning America that there was a "great possibility" that he would run for President in 2008.

- ^ On May 20, Gingrich said he was "thinking about thinking about running" on Meet the Press. http://www.ontheissues.org/Archive/2007_Meet_the_Press_Newt_Gingrich.htm

- ^ CNN, Gingrich edges closer to run

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/us/AP-Gingrich-2008.html?hp

- Books

- Fenno Jr., Richard F. (2000). Congress at the Grassroots: Representational Change in the South, 1970–1998. UNC Press. ISBN 0-8078-4855-7.

- Journals

- Little, Thomas H. (1998). "On the Coattails of a Contract: RNC Activities and Republicans Gains in the 1994 State Legislative Elections". Political Research Quarterly. 51 (1): 173–190.

- Web

- "GINGRICH, Newton Leroy — Biographical Information". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Titles List". Library of Congress Online Catalog.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Ancestry of Newt Gingrich

16 — A recent speech 17 — Another recent speech

External links

- Biography at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Financial information (federal office) at the Federal Election Commission

- Profile at Vote Smart

- Senior Fellow at AEI, The American Enterprise Institute

- Distinguished Visiting Fellow at Stanford's Hoover Institute, The Hoover Institute

- Winning the Future, a weekly column by Gingrich at Human Events

- The Genuine Danger of Terrorism — Gingrich Speech in New Hampshire

- The New York Times — Newt Gingrich News news stories and commentary

- Profile: Newt Gingrich, Notable Names Database

- On the Issues — Newt Gingrich issue positions and quotes

- The Long March of Newt Gingrich PBS Frontline, Peter Boyer and Stephen Talbot, January 16, 1996. transcript chronology interviews work and writings

- Washington Post — The Presidential Field: Newt Gingrich profile and collected Post coverage

- Template:Dmoz

- Mother Jones expose detailing the earliest days of Gingrich's political career, November 1, 1984

- Gingrich comment on shutdown labeled 'bizarre' by White House CNN, November 16, 1995

- Newt Gingrich's 1996 GOPAC memo — A Key Mechanism of Control

- Salon contemporary comments on Gingrich's resignation as Speaker, November, 1998

- Salon on Gingrich's resignation, November, 1998

- PBS Gingrich interview on the Tavis Smiley show, January 30, 2006

- The Gingrich RX ScribeMedia.org, December 15, 2006

- Gingrich wants to restrict freedom of speech?

- Grassroots campaigns

- VoteNewt.net — campaign for people to vote Newt in 2008

- 1943 births

- Alternate history writers

- American adoptees

- American Enterprise Institute

- American political writers

- Baptists from the United States

- Bohos

- Clinton Administration

- Congressional scandals

- Former global warming skeptics

- Fox News Channel

- German-American politicians

- Kennesaw State University people

- Literary collaborators

- Living people

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Georgia

- Military brats

- People from Columbus, Georgia

- People from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

- People from McLean, Virginia

- Political sex scandals

- Speakers of the United States House of Representatives

- Time magazine Persons of the Year

- Tulane University alumni

- University of West Georgia