Calvin and Hobbes: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

==Video game== |

==Video game== |

||

People are still wondering if theres going to be a [[Calvin and hobbes Video game]] Acording to |

People are still wondering if theres going to be a [[Calvin and hobbes Video game]] Acording to |

||

[[Bill |

[[Bill watterson]] he can not decide if there is going to be one |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

Revision as of 21:08, 9 November 2007

| Calvin and Hobbes | |

|---|---|

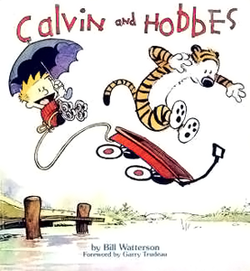

Calvin and Hobbes took many wagon rides over the years. This one showed up on the cover of the first collection of comic strips. | |

| Author(s) | Bill Watterson |

| Website | www.gocomics.com/calvinandhobbes/ Calvin and Hobbes |

| Current status/schedule | Concluded |

| Launch date | 1985-11-18 |

| End date | 1995-12-31 |

| Syndicate(s) | Universal Press Syndicate |

| Publisher(s) | Andrews McMeel Publishing |

Calvin and Hobbes is a comic strip written and illustrated by Bill Watterson, following the humorous antics of Calvin, an imaginative six-year old boy, and Hobbes, his energetic and sardonic—albeit stuffed—tiger. The pair are named after John Calvin, a 16th century French Reformation theologian, and Thomas Hobbes, a 17th century English political philosopher.[1] The strip was syndicated daily from November 18, 1985 to December 31, 1995. At its height, Calvin and Hobbes was carried by over 2,400 newspapers worldwide. To date, more than 30 million copies of the 18 Calvin and Hobbes books have been printed,[2] and popular culture is still replete with references to the strip.

The strip is vaguely set in the contemporary Midwestern United States, on the outskirts of suburbia, a location probably inspired by Watterson's home town of Chagrin Falls, Ohio. Calvin and Hobbes appear in most of the strips, while very few focus on other members of Calvin's family. The broad themes of the strip deal with Calvin's flights of fantasy, his friendship with Hobbes, his misadventures, his views on a diverse range of political and cultural issues and his relationships and interactions with his parents, classmates, educators, and other members of society. The dual nature of Hobbes is also a recurring motif. Calvin sees Hobbes one way (alive), while other characters see him as something else (a stuffed animal).

Even though the series does not mention specific political figures like political strips such as Garry Trudeau's Doonesbury, it does examine broad issues like environmentalism and the flaws of opinion polls.[3] A number of cartoons feature Calvin announcing the results of "polls of household six-year-olds" to his father, treating his father's position as though it were an elected political office.

Because of Watterson's strong anti-merchandising sentiments[4] and his reluctance to return to the spotlight, almost no legitimate Calvin and Hobbes merchandise exists outside of the book collections. Some officially approved items were created for marketing purposes and are now sought by collectors.[5] Two notable exceptions to the licensing embargo were the publication of two 16-month wall calendars and the textbook Teaching with Calvin and Hobbes.[6] However, the strip's immense popularity has led to the appearance of various "bootleg" items, including T-shirts, keychains, bumper stickers, and window decals, often including obscene language or references wholly uncharacteristic of the whimsical spirit of Watterson's work.

Video game

People are still wondering if theres going to be a Calvin and hobbes Video game Acording to Bill watterson he can not decide if there is going to be one

History

Calvin and Hobbes was first conceived when Watterson, having worked in an advertising job he detested,[7] began devoting his spare time to cartooning, his true love. He explored various strip ideas but all were rejected by the syndicates to which he sent them. Watterson did, however, receive a positive response to one strip, which featured a side character (the main character's little brother) who had a stuffed tiger. Told that these characters were the strongest, Watterson began a new strip centered on them.[8] The syndicate (United Features Syndicate) that gave him this advice rejected the new strip, and Watterson endured a few more rejections before Universal Press Syndicate decided to take it.[9][4]

The first strip was published on November 18, 1985 and the series quickly became a hit. Within a year of syndication, the strip was published in roughly 250 newspapers. By April 1 1987, only sixteen months after the strip began, Watterson and his work were featured in an article by the Los Angeles Times.[4] Calvin and Hobbes twice earned Watterson the Reuben Award from the National Cartoonists Society, in the Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year category, first in 1986 and again in 1988. He was nominated again in 1992. The Society awarded him the Humor Comic Strip Award for 1988.[10]

Before long, the strip was in wide circulation outside the United States; for more information on publication in various countries and languages, see Calvin and Hobbes in translation.

Watterson took two extended breaks from writing new strips—from May 1991 to February 1992, and from April through December of 1994.

In 1995, Watterson sent a letter via his syndicate to all editors whose newspapers carried his strip. It contained the following:

I will be stopping Calvin and Hobbes at the end of the year. This was not a recent or an easy decision, and I leave with some sadness. My interests have shifted however, and I believe I've done what I can do within the constraints of daily deadlines and small panels. I am eager to work at a more thoughtful pace, with fewer artistic compromises. I have not yet decided on future projects, but my relationship with Universal Press Syndicate will continue. That so many newspapers would carry Calvin and Hobbes is an honor I'll long be proud of, and I've greatly appreciated your support and indulgence over the last decade. Drawing this comic strip has been a privilege and a pleasure, and I thank you for giving me the opportunity.

The 3,160th and final strip ran on Sunday, December 31, 1995.[2] It depicted Calvin and Hobbes outside in freshly-fallen snow, reveling in the wonder and excitement of the winter scene. "It's a magical world, Hobbes, ol' buddy… Let's go exploring!" Calvin exclaims as they zoom off on their sled,[11] leaving, according to one critic, "a hole in the comics page that no strip has been able to fill."[12]

Syndication and Watterson's artistic standards

From the outset, Watterson found himself at odds with the syndicate, which urged him to begin merchandising the characters and touring the country to promote the first collections of comic strips; Watterson refused. To him, the integrity of the strip and its artist would be undermined by commercialization, which he saw as a major negative influence in the world of cartoon art.[13]

Watterson also grew increasingly frustrated by the gradual shrinking of available space for comics in the newspapers. He lamented that without space for anything more than simple dialogue or spare artwork, comics as an art form were becoming dilute, bland, and unoriginal.[14][13] Watterson strove for a full-page version of his strip (as opposed to the few cells allocated for most strips). He longed for the artistic freedom allotted to classic strips such as Little Nemo and Krazy Kat, and he gave a sample of what could be accomplished with such liberty in the opening pages of the Sunday strip compilation, The Calvin and Hobbes Lazy Sunday Book.[15]

During Watterson's first sabbatical from the strip, Universal Press Syndicate continued to charge newspapers full price to re-run old Calvin and Hobbes strips. Few editors approved of the move, but the strip was so popular that they had little choice but to continue to run it for fear that competing newspapers might pick it up and draw its fans away.

Then, upon Watterson's return, Universal Press announced that Watterson had decided to sell his Sunday strip as an unbreakable half of a newspaper or tabloid page. Many editors and even a few cartoonists, such as Bil Keane (The Family Circus), criticized him[16] for what they perceived as arrogance and an unwillingness to abide by the normal practices of the cartoon business—a charge that Watterson ignored. Watterson had negotiated the deal to allow himself more creative freedom in the Sunday comics. Prior to the switch, he had to have a certain number of panels with little freedom as to layout (because in different newspapers the strip would appear at a different width); afterwards, he was free to go with whatever graphic layout he wanted, however unorthodox. His frustration with the standard space division requirements is evident in strips before the change; for example, a 1988 Sunday strip published before the deal is one large panel, but with all the action and dialogue in the bottom part of the panel so editors could crop the top part if they wanted to fit the strip into a smaller space. Watterson's explanation for the switch:

I took a sabbatical after resolving a long and emotionally draining fight to prevent Calvin and Hobbes from being merchandised. Looking for a way to rekindle my enthusiasm for the duration of a new contract term, I proposed a redesigned Sunday format that would permit more panel flexibility. To my surprise and delight, Universal responded with an offer to market the strip as an unbreakable half page (more space than I'd dared to ask for), despite the expected resistance of editors.

To this day, my syndicate assures me that some editors liked the new format, appreciated the difference, and were happy to run the larger strip, but I think it's fair to say that this was not the most common reaction. The syndicate had warned me to prepare for numerous cancellations of the Sunday feature, but after a few weeks of dealing with howling, purple-faced editors, the syndicate suggested that papers could reduce the strip to the size tabloid newspapers used for their smaller sheets of paper. … I focused on the bright side: I had complete freedom of design and there were virtually no cancellations.

For all the yelling and screaming by outraged editors, I remain convinced that the larger Sunday strip gave newspapers a better product and made the comics section more fun for readers. Comics are a visual medium. A strip with a lot of drawing can be exciting and add some variety. Proud as I am that I was able to draw a larger strip, I don't expect to see it happen again any time soon. In the newspaper business, space is money, and I suspect most editors would still say that the difference is not worth the cost. Sadly, the situation is a vicious circle: because there's no room for better artwork, the comics are simply drawn; because they're simply drawn, why should they have more room?[17]

Calvin and Hobbes remained extremely popular after the change and thus Watterson was able to expand his style and technique for the more spacious Sunday strips without losing carriers.

Merchandising

Bill Watterson is notable for his insistence that cartoon strips should stand on their own as an art form, and he has resisted the use of Calvin and Hobbes in merchandising of any sort.[9] This insistence stuck despite the fact that it could have generated millions of dollars per year in additional personal income. Watterson explains in a 2005 press release:

Actually, I wasn't against all merchandising when I started the strip, but each product I considered seemed to violate the spirit of the strip, contradict its message, and take me away from the work I loved. If my syndicate had let it go at that, the decision would have taken maybe 30 seconds of my life.[18]

Watterson did ponder animating Calvin and Hobbes, and has expressed admiration for the art form. In a 1989 interview in The Comics Journal, Watterson states:

If you look at the old cartoons by Tex Avery and Chuck Jones, you'll see that there are a lot of things single drawings just can't do. Animators can get away with incredible distortion and exaggeration . . . because the animator can control the length of time you see something. The bizarre exaggeration barely has time to register, and the viewer doesn’t ponder the incredible license he's witnessed. In a comic strip, you just show the highlights of action—you can't show the buildup and release . . . or at least not without slowing down the pace of everything to the point where it's like looking at individual frames of a movie, in which case you've probably lost the effect you were trying to achieve. In a comic strip, you can suggest motion and time, but it's very crude compared to what an animator can do. I have a real awe for good animation.[13]

After this he was asked if it was "a little scary to think of hearing Calvin's voice." He responded that it was "very scary," and that although he loved the visual possibilities of animation, the thought of casting voice actors to play his characters was uncomfortable. He was also unsure he wanted to work with an animation team, as he had done all previous work by himself. Ultimately, Calvin and Hobbes was never made into an animated series. Watterson later stated in the "Calvin and Hobbes Tenth Anniversary Book" that he liked the fact that his strip was a "low-tech, one-man operation," and took great pride in the fact that he drew every line and wrote every word on his own.[19]

Except for the books, two 16-month calendars (1988–1989 and 1989–1990), Teaching with Calvin and Hobbes,[6] and one T-shirt for a traveling art exhibit on comics, virtually all Calvin and Hobbes merchandise, including T-shirts as well as the ubiquitous stickers for automobile rear windows which depict Calvin urinating on a company's or sports team's name or logo, is unauthorized. As Watterson pointed out during the notes of one of the collection books, the original image was of Calvin filling up a water balloon from a faucet. After threat of a lawsuit alleging infringement of copyright and trademark, some of the sticker makers replaced Calvin with a different boy, while other makers ignored the issue.[citation needed] Watterson wryly commented, "I clearly miscalculated how popular it would be to show Calvin urinating on a Ford logo."[18] Some legitimate special items were produced, such as promotional packages to sell the strip to newspapers, but these were never sold outright.

Style and influences

Calvin and Hobbes strips are characterized by sparse but careful craftsmanship, intelligent humor, poignant observations, witty social and political commentary, and well-developed characters. Precedents to Calvin's fantasy world can be found in Crockett Johnson's Barnaby, Charles M. Schulz's Peanuts, Percy Crosby's Skippy, Berkeley Breathed's Bloom County, and George Herriman's Krazy Kat, while Watterson's use of comics as sociopolitical commentary reaches back to Walt Kelly's Pogo. Schulz and Kelly, in particular, influenced Watterson's outlook on comics during his formative years.[9]

Notable elements of Watterson's artistic style are his characters' diverse and often exaggerated expressions (particularly those of Calvin), elaborate and bizarre backgrounds for Calvin's flights of imagination, well-captured kinetics, and frequent visual jokes and metaphors. In the later years of the strip, with more space available for his use, Watterson experimented more freely with different panel layouts, stories without dialogue, and greater use of whitespace. He also made a point of not showing certain things explicitly: the "Noodle Incident" and the children's book Hamster Huey and the Gooey Kablooie were left to the reader's imagination, where Watterson was sure they would be “more outrageous” than he could portray.[20]

Watterson's technique started with minimalist pencil sketches (though the larger Sunday strips often required more elaborate work); he then would use a small sable brush and India ink to complete most of the remaining drawing. He was careful in his use of color, often spending a great deal of time in choosing the right colors to employ for the weekly Sunday strip.[21]

Art and academia

Watterson has used the strip to criticize the artistic world, principally through Calvin's unconventional creations of snowmen. When Miss Wormwood complains that he is wasting class time drawing incomprehensible things (a Stegosaurus in a rocket ship, for example), Calvin proclaims himself "on the cutting edge of the avant-garde." He begins exploring the medium of snow when a warm day melts his snowman. His next sculpture "speaks to the horror of our own mortality, inviting the viewer to contemplate the evanescence of life," much in the vein of Ecclesiastes. Over the years, Calvin's creative instincts diversify to include sidewalk drawings (or as he terms them, examples of "suburban postmodernism").

Watterson also directed criticism toward the academic world. Calvin writes a "revisionist autobiography", recruiting Hobbes to take pictures of him doing stereotypical kid activities like playing sports in order to make him seem more well-adjusted. In another strip, he carefully crafts an "artist's statement," knowing that such essays convey more messages than artworks themselves ever do (Hobbes blandly notes “You misspelled Weltanschauung.”). He indulges in what Watterson calls “pop psychobabble” to justify his destructive rampages and shift blame to his parents, citing "toxic codependency." Once, he pens a book report, based on the theory that the purpose of academic scholarship is to "inflate weak ideas, obscure poor reasoning, and inhibit clarity," entitled The Dynamics of Interbeing and Monological Imperatives in Dick and Jane: A Study in Psychic Transrelational Gender Modes. Displaying his creation to Hobbes, he remarks, "Academia, here I come!" Watterson explains that he adapted this jargon (and similar examples from several other strips) from an actual book of art criticism.[20]

Overall, Watterson's satirical essays serve to attack both sides, criticizing both the commercial mainstream and the artists who are supposed to be "outside" it. Walking contemplatively through the woods, not long after he began drawing his "Dinosaurs In Rocket Ships" series, Calvin tells Hobbes:

The hard part for us avant-garde post-modern artists is deciding whether or not to embrace commercialism. Do we allow our work to be hyped and exploited by a market that's simply hungry for the next new thing? Do we participate in a system that turns high art into low art so it's better suited for mass consumption?

Of course, when an artist goes commercial, he makes a mockery of his status as an outsider and free thinker. He buys into the crass and shallow values art should transcend. He trades the integrity of his art for riches and fame.

Oh, what the heck. I'll do it.

Visual distortions

On several occasions, Watterson drew strips with strange visual distortions: inverted colors, objects turning "neo-cubist," or other distortions. Only Calvin is able to perceive these alterations, which seem to illustrate his own shifting world view.

In the Tenth Anniversary Book, Watterson explains that some of these strips were metaphors for his own experiences, illustrating, for example, his conflicts with his syndicate: a 1989 Sunday strip—normally in color—was drawn almost entirely in an inverted monochrome. Calvin is accused by his father of seeing issues "in black and white," — an accusation sometimes leveled at Watterson regarding his refusal to license the strip — to which he replies "Sometimes that's the way things are!" — a retort used by Watterson himself.

Passage of time

When the strips were originally published, Calvin's settings were seasonally appropriate for the Northern Hemisphere. Calvin would be seen building snowmen or sledding during the wintertime, and outside activities such as water balloon fights would replace school during the summer. Christmas and Halloween strips were run during those times of year.

Although Watterson depicts several years' worth of holidays, school years, summer vacations, and camping trips, and characters are aware of multiple "current" years (such as "'94 model toboggans," "Vote Dad in '88," the '90s as the new decade, etc.) Calvin is never shown to age nor have any birthday celebrations. (The only birthday shown was that of Susie Derkins). Such temporal distortions are fairly common among comic strips; consider the children in Peanuts, who existed without aging for decades. Likewise, the characters in Krazy Kat celebrate the New Year but never grow old, and young characters like Ignatz Mouse's offspring never seem to grow up. These uses of a floating timeline are very unlike the pre-2007 For Better or For Worse series, in which the characters age each year with their reading audience as well as get married and have children.

While Calvin does not grow older in the strip, reference is made in two strips—from November 18 and 19, 1995—to Calvin having once been two and three years old and now feeling that "a lifetime of experience has left [him] bitter and cynical." "This is a photograph of me when I was two," he tells Hobbes while flipping through a family photo album, and later remarks: "Isn't it weird that one's own past can seem unreal?" So while Calvin's age remains perpetually suspended at six within the realm of the strip, acknowledgment is made to a time before Calvin was as old as he is now depicted. Since temporal suspension is such a common narrative device among many comic strips, readers are likely to suspend disbelief, as with regard to Calvin's precocious vocabulary, accepting that he "was never a literal six-year-old".[20]

Ironically, in an early strip, Calvin's dad criticizes him for not living in the moment, proclaiming, "Yeah, I know, you think you're going to be six all your life."

Social criticisms

In addition to his criticisms of art and academia, Watterson often used the strip to comment on American culture and society, admitting that the content of the strips has emerged as a sort of self-portrait. With rare exception, the strip avoids reference to actual people or events. Watterson's commentary is therefore necessarily generalized. He expresses frustration with public decadence and apathy, with commercialism, and with the pandering nature of the mass media. Calvin is often seen "glued" to the television, while his father speaks with the voice of the author, struggling to impart his values on Calvin.

Watterson's vehicle for criticism is often Hobbes who comments on Calvin's unwholesome habits from a more cynical perspective. He is more likely to make a wry observation than actually intervene; alternatively, he may even watch as Calvin inadvertently makes the point himself. In one instance, Calvin tells Hobbes about a science fiction story he has read in which machines turn humans into zombie slaves. Hobbes makes a comment about the irony of machines controlling us instead of the other way around, when Calvin then exclaims, "Hey! What time is it?? My TV show is on!" and sprints back inside to watch it, leaving Hobbes to contemplate the irony of the situation. This subtlety becomes a poignant criticism in and of itself and has been established as one of Watterson's trademarks.[citation needed]

Watterson also expresses his despair at the human condition in a far more philosophical manner.[citation needed] Calvin admires Hobbes for not being human, something the tiger trumpets often. Calvin's affection for Hobbes in turn adds to his misanthropy. Some of the most tender and emotional moments in the strips are when Calvin and Hobbes are together by themselves and vocalizing their mutual affections. "Not so hard," Calvin sobs, embraced by his animal friend, "...You squeeze my tears out." Calvin often directly mocks his father for joining the "rat race" and talks often with Hobbes of his resolve to behave like an animal in order to "get the most out of life".

Main characters

Calvin

First appearance: November 18 1985

Named after 16th-century theologian John Calvin (founder of Calvinism and a strong believer in predestination), Calvin is an impulsive, sometimes overly creative, imaginative, energetic, curious, intelligent, and often selfish six-year-old, whose last name the strip never gives [22]. Despite his low grades, Calvin has a wide vocabulary range that rivals that of an adult as well as an emerging philosophical mind, implying that he comes from a naturally literate family, as seen in this anecdote:

- Calvin: "Dad, are you vicariously living through me in the hope that my accomplishments will validate your mediocre life and in some way compensate for all of the opportunities you botched?"

- Calvin's father: "If I were, you can bet I'd be re-evaluating my strategy."

- Calvin (later, to his mother): "Mom, Dad keeps insulting me."

He has also said, "You know how Einstein got bad grades as a kid? Well, mine are even worse!" He commonly wears his distinctive red-and-black striped shirt, black jeans, and magenta sneakers. He is also a compulsive reader of comic books and has a strong thirst for pop culture, including trendy or modern apparel, pulp fiction, and electronic devices—which mostly remain a wish throughout the series. Nevertheless, his often-vulgar experiences seem to give him valuable experiences, contrasting his preferences (and unusual derivations of thoughts) to the standards and morals his parents set to him. Calvin chews gum regularly and subscribes to a magazine called "Chewing". Hobbes occasionally challenges Calvin's strange obsession, but otherwise just remains calmly waiting for the strip to end. Throughout the series, he is also revealed to be a "trial and error" sort of person. Watterson has described Calvin thus:

- "Calvin is pretty easy to do because he is outgoing and rambunctious and there's not much of a filter between his brain and his mouth."[23]

- "I guess he's a little too intelligent for his age. The thing that I really enjoy about him is that he has no sense of restraint, he doesn't have the experience yet to know the things that you shouldn't do."

Calvin, as the protagonist, often breaks the fourth wall.

Hobbes

First appearance: November 18 1985

In the classic comic tradition of sidekicks, Hobbes represents Calvin's potential maturity and externalized conscience. A comic about a young boy throwing slushballs into a neighbor girl's head would be sad and trite without Hobbes there to wisely tease him, "You think she's cute, right?"

From everyone else's point of view, Hobbes is Calvin's stuffed tiger. From Calvin's point of view, however, Hobbes is an anthropomorphic tiger, much larger than Calvin and full of his own attitudes and ideas. But when the perspective shifts to any other character, readers again see merely a stuffed animal, usually seated at an off-kilter angle. This is, of course, an odd dichotomy, and Watterson explains it thus:

When Hobbes is a stuffed toy in one panel and alive in the next, I'm juxtaposing the "grown-up" version of reality with Calvin's version, and inviting the reader to decide which is truer.[9]

Hobbes' inanimacy is called into question, however, when he pounces on Calvin (often leaving Calvin disheveled) and in one incident, ties him to a chair in such a way that his father is unable to understand how he could have done it himself. In another Hobbes leaves Calvin hanging by the seat of his pants from a tree branch above Calvin's head. Also, in a very early strip, Calvin says that Hobbes ate a classmate of his (and Hobbes seems to verify this). No other reference to Hobbes doing anything to another person is ever made, and this incident is probably just a humorous throwaway line.

Hobbes is named after the 17th-century philosopher Thomas Hobbes, who had what Watterson described as "a dim view of human nature."[20] Thomas Hobbes' most famous work is titled Leviathan, in which his description of the human condition also mirrors a physical description of Calvin as "...nasty, brutish and short". Hobbes is much more rational and aware of consequences than Calvin, but seldom interferes with Calvin's troublemaking beyond a few oblique warnings—after all, Calvin will be the one to get in trouble for it, not Hobbes. Hobbes also has the habit of regularly stalking and pouncing on Calvin, most often when Calvin returns home from school. Hobbes is sarcastic when Calvin is being hypocritical about things he dislikes [24].

Although the first strips clearly show Calvin capturing Hobbes by means of a snare (with tuna fish sandwich as the bait), a later comic (August 1, 1989) seems to imply that Hobbes is, in fact, older than Calvin, and has been around his whole life. Watterson eventually decided that it was not important to establish how Calvin and Hobbes had first met.[20]

Supporting characters

It has been suggested that this article be merged with Secondary characters in Calvin and Hobbes and Talk:Secondary characters in Calvin and Hobbes#Merger proposal. (Discuss) Proposed since September 2007. |

Calvin's family

Dad's first appearance: November 18 1985

Mom's first appearance: November 26 1985

Calvin's mother and father are for the most part typical Middle American middle-class parents. Like many other characters in the strip, their relatively down-to-earth and sensible attitudes serve primarily as a foil for Calvin's outlandish behavior. At the beginning of the strip, Watterson says some fans were angered by the way Calvin's parents thought of Calvin (his father once remarked that he had really wanted a dog). Calvin’s father is a patent attorney (Bill Watterson has said that the specific was more humorous than the generic); his mother is a stay-at-home mom. Both parents go through the entire strip unnamed, except as "Mom" and "Dad," or such nicknames as "hon" and "dear" when referring to each other. Watterson has never given Calvin's parents names "because as far as the strip is concerned, they are important only as Calvin's mom and dad." This ended up being somewhat problematic when Calvin's Uncle Max was in the strip for a week and could not refer to the parents by name and was one of the main reasons that Max never reappeared.[20]

Susie Derkins

First appearance: December 5 1985

Susie Derkins, the only important character with both a given name and a family name, is a classmate of Calvin's who lives in his neighborhood. Named for the pet beagle of Watterson's wife's family,[25] she first appeared early in the strip as a new student in Calvin's class. In contrast with Calvin, she is polite and diligent in her studies, and her imagination usually seems mild-mannered and civilized, consisting of stereotypical young girl games such as playing house or having tea parties with her stuffed animals. Her approach to these games is arguably more modern, however, some might say even cynical. Though both of them hate to admit it, Calvin and Susie have quite a bit in common. For example, Susie is shown on occasion with a stuffed rabbit dubbed "Mr. Bun," and Calvin, of course, has Hobbes. It is also hinted that while Susie plays the goody two shoes, she has a mischievous streak as wide as Calvin's, shown through her gleeful finger pointing and "encouragement" for Calvin's antics. Watterson admits that Calvin and Susie have a bit of a nascent crush on each other, and that Susie is inspired by the type of women that he himself finds attractive. Her relationship with Calvin, though, is frequently conflicted, and never really becomes sorted out. Their love/hate relationship is most obvious in some of the early comics involving Susie and Calvin's relationships, when some punchlines revolved around Susie and Calvin going out of their way to malign each other, followed immediately by each thinking romantic thoughts about the other.

Miss Wormwood

First appearance: November 21 1985

Miss Wormwood is Calvin's world-weary teacher, named after the apprentice devil in C.S. Lewis' The Screwtape Letters. She perpetually wears polka-dotted dresses, and serves, like others, as a foil to Calvin's mischief. Throughout the strip's run, we get clues that Miss Wormwood is waiting to retire, takes a lot of medication, and is apparently a heavy smoker and drinker (habits certainly not helped by Calvin's antics). Watterson has said that he has a great deal of sympathy for Miss Wormwood, who is clearly stressed over trying to keep rowdy children under control so they can learn something. She once ironically commented, "It's not enough that we have to be disciplinarians. Now we need to be psychologists," clearly speaking for teachers in general.

Rosalyn

Rosalyn is a teenage high school senior and Calvin's official babysitter whenever Calvin's parents need a night out. She is also his swimming lessons teacher. She is the only babysitter able to tolerate Calvin's antics, which she uses to demand raises and advances from Calvin's desperate parents. She is also, according to Watterson, the only person Calvin truly fears. She does not hesitate to play as dirty as he does. She appears at the door in one strip with a baseball bat and a catchers outfit. Calvin and Rosalyn usually do not get along, except in one case where she played "Calvinball" with him in exchange for him doing his homework. Rosalyn's boyfriend, Charlie, never appears in the strip but calls her occasionally, calls that are often interrupted by Calvin. Originally she was created as a nameless, one-shot character with no plan for her to appear again; however, Watterson decided he wanted to retain her unique ability to intimidate Calvin, which ultimately led to many more appearances.

Moe

First appearance: February 6 1986

Moe is the archetypical bully character in Calvin and Hobbes, "a six-year-old who shaves," who always shoves Calvin against walls, demands his lunch money, and calls him "Twinky." Moe is the only regular character who speaks in an unusual font: his (frequently monosyllabic) dialogue is shown in crude, lower-case letters. Watterson describes Moe as "big, dumb, ugly and cruel," and a summation of "every jerk I've ever known." And while Moe is not smart, he is, as Calvin puts it, streetwise: "That means he knows what street he lives on."

Principal Spittle

First appearance: November 29, 1985

Principal Spittle—the principal at Calvin's school—is almost always featured in the final panel of a strip in which Calvin is disobedient, unruly, inattentive, or ridiculous during class. These panels usually feature Calvin trying to explain himself while Spittle stares at him, obviously annoyed (sometimes he also appears bored). It has been implied that, like Miss Wormwood, Spittle dislikes his job largely due to Calvin's behavior—Calvin has been to Spittle's office enough to make his file of transgressions the thickest in the entire school. Spittle also dreads dealing with children who break down in tears when they arrive at his office after disobeying only one rule.

Other recurring characters

The strip primarily focuses on Calvin, Hobbes, and the above mentioned secondary characters. Other characters who have appeared in multiple storylines include Calvin's family doctor (whom Calvin frequently gives a hard time during his check-ups), and the extra-terrestrials Galaxoid and Nebular—to whom Calvin sold the Earth in exchange for a collection of leaves from their planet complete with scientific classifications (in order to avoid doing that assignment for school).

Calvin's roles

Calvin imagines himself as a great many things, from dinosaurs to elephants, jungle-farers and superheroes. Three of his alter egos are well-defined and recurring: As "Stupendous Man", he pictures himself as a superhero in disguise. In reality he is wearing a mask and a cape made by his mother. Stupendous Man almost always "suffers defeat," either from Rosalyn, or his mother. However, all of his victories are, as Calvin puts it, moral. "Spaceman Spiff" is a heroic spacefarer. As Spiff, Calvin battles aliens (typically his parents or teacher) and travels to distant planets (his house, school or neighborhood). The rare "Tracer Bullet," a hardboiled private eye, says he has eight slugs in him: "one's lead, and the rest are bourbon." In one story, Bullet is called to a case, in which a "pushy dame" (Calvin's mother) accuses him of destroying an expensive lamp (broken as a result of an indoor football game between Calvin and Hobbes).

As a comparison, each of the three is used at least once to solve a test: "The mild-mannered Calvin" slips into his locker on the pretext of getting a drink of water, Stupendous Man bursts out. He runs into class to complete Calvin's paper with his powers, all the while providing his own narration and narrowly avoiding Miss Wormwood, before he's caught making a dramatic exit. Calvin flunked the test. Spaceman Spiff crashes planets Mysterio 5 and Mysterio 6 together; 5 is pulverized and 6 remains, therefore 5+6=6. Tracer Bullet provides a grim monologue where he's caught in a web of intrigue involving a "Numbers" Racket(a quiz), the Derkins dame proves out to have been silenced (Susie refuses to tell Calvin the answer), and a hired thug roughs him up (Miss Wormwood keeps him in his seat) before he gets on the trail of a "Mr. Billion."

Recurring subject matter

There are several repeating themes in the work, a few involving Calvin's real life, and many stemming from his incredible imagination. Some of the latter are clearly flights of fantasy, while others, like Hobbes, are of an apparently dual nature and do not quite work when presumed real or unreal.

Cardboard boxes

Over the years Calvin has had several adventures involving corrugated cardboard boxes which he adapts for many different uses. Some of his many uses of cardboard boxes include:

- Transmogrifier

- Flying time machine

- Duplicator (ethicator included)

- Atomic Cerebral Enhance-O-Tron

- Emergency G.R.O.S.S. meeting "box of secrecy"

- A stand for selling things, such as "lemonade"[26] and a "frank appraisal of your looks".[27]

Building the Transmogrifier is accomplished by turning a cardboard box upside-down, attaching an arrow to the side and writing a list of choices on the box (to turn into an animal not stated on the box, the name of the animal is written on the remaining space). Upon turning the arrow to a particular choice and pushing a button, the transmogrifier instantaneously rearranges the subject's "chemical configuration" (accompanied by a loud zap).[28] Calvin later invented a Transmogrifier "Gun" patterned after a water pistol.[29]

The Duplicator was also made from a cardboard box, except this time it was turned on its side. The "zap" heard after a person was successfully transmogrified was replaced with a "boink," coining the title of one of the collections after Hobbes remarks, "Scientific progress goes 'boink'?" Calvin intended to clone himself and let the clone do his work for him. However, the clone, being just like Calvin, refuses to do any work.[30] In a future strip Calvin solves this problem by adding an Ethicator to the Duplicator, thus copying only Calvin's good side. "The ethicator must've done some deep digging to unearth him!" says Hobbes; Calvin, oblivious, replies, "Talk about someone easy to exploit!" Susie comments, "If that [you are Calvin's good side] was true, you'd be a lot smaller."[31]

The Time Machine was made from the same box, this time right-side up. Passengers climb into the open top, and must be wearing protective goggles while in time-warp. Calvin first intends to travel to the future and obtain future technology that he could use to become rich in the present time. Unfortunately, he faces the wrong way as he steers and ends up in prehistoric times.[32] Later, Calvin learns from this mistake and returns to the time period to take photos of the dinosaurs.[33] In another instance, Calvin goes to the near future to retrieve his supposedly-finished homework. It is, however, unfinished, because his future self (two hours into the future) "went to the future to get it." Calvin responds, "Yeah, and here I am! Where is it?!" The 6:30 Hobbes then says to the 8:30 Hobbes, "I knew this would never work," the response being, "Right as always, Hobbes."[34]

The Atomic Cerebral Enhance-O-Tron (or quite simply, a thinking cap) was created from the same cardboard box, turned open-side-down, but with three strings attached to it. The three strings were used for input, output, and a grounding string that functioned like a lightning rod for brainstorms so Calvin could keep his ideas grounded in reality. Hobbes comments that it was probably too late for that. The strings are tied to a metal colander, which served as the thinking cap. When used, the wearer of the thinking cap would receive a boost in intelligence, resulting in the head swelling. The intelligence boost, however, is temporary. When it wears off, the subject's head reverts to its normal size. Calvin created it in order to be able to come up with a topic for his homework.[35]

The box was used once as an emergency G.R.O.S.S. meeting "box of secrecy" when Calvin's mother allowed Susie Derkins to come to Calvin's house after school one day. Hobbes voiced the opinion that the box needed air holes; Calvin replied, "Too risky. The box of secrecy must remain secure."[36]

Calvinball

Other kids' games are all such a bore!

They've gotta have rules and they gotta keep score!

Calvinball is better by far!

It's never the same! It's always bizarre!

You don't need a team or a referee!

You know that it's great, 'cause it's named after me!

— Calvinball, as described by Calvin[37]

Calvinball is a game played by Calvin and Hobbes as a rebellion against organized team sports; according to Hobbes "No sport is less organized than Calvinball!"[38] The game was first introduced in a three-week story in 1990, where Calvin is bullied into signing up to play baseball, cursed when he proves worthless at it and insulted when he quits.[38] Calvin and Hobbes usually play by themselves, although Rosalyn plays once and does very well for herself after eventually figuring the game out.[39] Most games Calvin and Hobbes play eventually turn into Calvinball.[40]

The only consistent rule is that Calvinball may never be played with the same rules twice.[41] Scoring is also arbitrary: Hobbes has reported scores of "Q to 12" and "oogy to boogy."[42] Equipment includes a volleyball (the titular "Calvinball"), a soccerball, a croquet set, a badminton set, assorted flags, bags, signs, and a hobby horse. Other things are included as needed, such as a bucket of ice-cold water, a water balloon, and various songs and poetry.[43] Players also wear masks similar to The Lone Ranger's and Zorro's—when asked why, Calvin answers "Sorry, no one's allowed to question the masks."[39] When asked how to play, Watterson states, "It's pretty simple: you make up the rules as you go."[44] Calvinball is essentially a game of wits and creativity rather than stamina or athletic skill, a prominent nomic (self-modifying) game, and one where Hobbes usually outwits Calvin himself.

Wagon and sled

Calvin and Hobbes frequently ride downhill in a wagon, sled, or toboggan, depending on the season, as a device to add some physical comedy to the strip and because, according to Watterson, "it's a lot more interesting […] than talking heads."[45] While the ride is sometimes the focus of the strip,[46] it also frequently serves as a counterpoint or visual metaphor while Calvin ponders the meaning of life, death, God, or a variety of other weighty subjects.[45][47] Most of their rides end in a spectacular crash when they ride off a cliff, leaving the sled battered and broken, and on one occasion, on fire in winter.[48] In the final strip, Calvin and Hobbes depart on their toboggan for possibilities unknown.[11]

Snowballs and snowmen

During winter, Calvin often engages in snowball fights usually throwing them at Susie but almost always resulting in Calvin getting buried in the snow as retaliation. Once, Calvin threw a snowball he was saving for three months and misses. As he moans about it, Susie scoops up the remains, bounces it menacingly in her hand, and pegs him in the chest(In the last panel, Calvin, covered in snow, comments,"The irony of this is sickening"). He sometimes teams up with Hobbes for snowball fights, but Calvin cannot seem to resist also sneaking up on Hobbes, who always seems to get the drop on him instead. This also happens during water balloon fights.

Calvin is also very talented at building snowmen, but he usually puts them in grotesque, horrific scenes that depict the snowmen dying or suffering in obscene ways (e.g., a snowman screaming with a tree growing through it, a snowman that has been cut in half by another snowman on a toboggan, a giant snow-squid devouring a crowd of snowmen, etc.). Such creations usually bring swift discipline from Calvin's parents. For example, after his mother sees him build a snowman bowling with another snowman's head, Calvin is summoned to the house, leaving him to remark to Hobbes, "First she says go out, now she says come in." In a notable storyline, Calvin builds a snowman and brings it to life using the power "invested in him by the mighty and awful Snow Demons." The snowman immediately proves to be evil (reminiscent of Frankenstein's monster) and becomes what Calvin calls a "deranged mutant killer monster snow goon." This storyline gave the title to the Calvin and Hobbes book Attack of the Deranged Mutant Killer Monster Snow Goons. In the end, Calvin succeeds in freezing the Snowgoons with a water hose, though he is caught by his parents and punished for leaving the house at night.

Calvin believes in the aforementioned "Snow Demons" as "gods" that control the weather, and that they require burned leaves as a sacrifice for a cold, snowy winter. When he tells his father this, his father says, "I'm not sure whether your grasp of meteorology or theology is the more appalling."

Calvin, unlike Hobbes, thinks of snowmen as a fine art. Bill Watterson has said that this is a parody of art's “pretentious blowhards.”[20] Once, out of ideas, Calvin signed the snow-covered landscape with a stick and declared all the world's snow as his own work of art, offering to sell it to Hobbes for a million dollars. Hobbes mellowly responds, "Sorry, it doesn't match my furniture," and walks away, leaving Calvin to contemplate, "The problem with being avant-garde is knowing who's putting on who."

G.R.O.S.S.

G.R.O.S.S. is Calvin's secret club, whose sole purpose is to exclude girls generally, and Susie Derkins specifically. The name is an acronym, reminiscent of Valerie Solanas' S.C.U.M. It stands for Get Rid Of Slimy girlS. Calvin admits "slimy girls" is a bit redundant, as—of course—all girls are slimy, "but otherwise it doesn't spell anything." After a misadventure with the car and a card table, G.R.O.S.S. relocated to a treehouse (and in one instance to beneath a cardboard box. This also had the first and only appearance of the club charter, after Calvin says that their secret plan doesn't need a secret code and Hobbes hands him the charter). Hobbes can climb up to the tree house, but Calvin requires a rope. Therefore, Hobbes refuses to drop down the rope until Calvin has said the password, which is over eight verses extolling tigers. Calvin and Hobbes are its only members, and each takes up multiple official titles while wearing newspaper chapeaux during meetings (Calvin is Dictator-For-Life, and Hobbes is President and First Tiger). The club has an anthem, but most of its words are unknown to outsiders. A surviving fragment of the anthem begins: "Oh Grohoooss! Best Club in the Cosmos . . .". Calvin often awards badges, promotions, etc., such as "Bottle Caps of Valor". Many G.R.O.S.S. plans to annoy or otherwise attack Susie have failed, including an incident when Calvin and Hobbes intended to soak Susie with a water balloon but ended up kidnapping her doll and sending a ransom note instead, to which Susie responded by kidnapping Hobbes; and another incident when Calvin and Hobbes drew up an elaborate map with a plan to hit Susie with snowballs while escaping on a sled (the last panel shows Calvin sitting on a sled saying, "Now if only it would snow!")[49]

The Noodle Incident

The famous “Noodle Incident” has never been fully explained, but the fact that Miss Wormwood knows that it occurred must mean that it happened at school. Calvin thought of a cover story which Hobbes was impressed by. He was caught, therefore his excuse was not believed. Hobbes repeatedly brings up the subject, and believes that Calvin’s cover story deserved a Pulitzer. The fact that Hobbes and even Santa have brought it up over the years means that it must have been very serious to be remembered now. The police and/or other emergency service vehicles were even involved in an unspecified incident that might have been the Noodle Incident.

- Calvin: Boy, did I get in trouble at school today. Wow.

- Hobbes: What did you do?

- Calvin: I don’t even want to talk about it.

- Hobbes: Did it have anything to do with those sirens around noon?

- Calvin: I SAID I DON’T WANT TO TALK ABOUT IT!

Hobbes frequently alludes to it, as illustrated in this strip.

- Calvin: This is the worst assignment ever! I’m supposed to think up a story, write it, and illustrate it by tomorrow! Do I look like a novelist? This is impossible! I can‘t tell stories!

- Hobbes: What about your explanation of the Noodle Incident?

- Calvin: That wasn’t a story! That was the unvarnished truth!

- Hobbes: Oh, don’t be so modest. You deserved a Pulitzer.

Santa Claus also brought it up on Christmas Eve, 1995, referring to him as the “Noodle Incident kid”. In the dream, the elves explain "the kid says he was framed...we're having trouble verifying the particulars. Accounts seem to vary.” When Calvin is asked about the Incident he usually replies "No one can prove I did that!!" A “Salamander Incident” is mentioned once, to which Calvin yells “Temporary insanity! That‘s all it was!”

Books

- For the complete list of books, see List of Calvin and Hobbes books.

There are eighteen Calvin and Hobbes books, published from 1987 to 2005. These include eleven "collections," which form a complete archive of the newspaper strips, except for a single daily strip from November 28, 1985 (the collections do contain a strip for this date, but it is not the same strip that appeared in some newspapers. The alternate strip, a joke about Hobbes taking a bath in the washing machine, has circulated around the Internet). "Treasuries" usually combine the two preceding collections (albeit leaving out some strips) with bonus material and include color reprints of Sunday comics.

Watterson included a unique Easter egg in The Essential Calvin and Hobbes. The back cover is a scene of a giant Calvin rampaging through a town. The scene is in fact a faithful reproduction of the town square (actually a triangle) in Watterson's home town of Chagrin Falls, Ohio. The giant Calvin has uprooted, and is holding in his hands, the Popcorn Shop, a small, iconic candy and ice cream shop overlooking the town's namesake falls.

A complete collection of Calvin and Hobbes strips, in three hardcover volumes with a total 1440 pages, was released on October 4, 2005, by Andrews McMeel Publishing. It also includes color prints of the art used on paperback covers, the treasuries' extra illustrated stories and poems, and a new introduction by Bill Watterson. It is notable, however, that the alternate 1985 strip is still omitted, and two other strips (January 7, 1987, and November 25, 1988) have altered dialogue.[50][51][52]

To celebrate the release, Calvin and Hobbes reruns were made available to newspapers from Sunday, September 4, 2005, through Saturday, December 31, 2005,[53][54] and Bill Watterson answered a select dozen questions submitted by readers.[18] Like other reprinted strips, weekday Calvin and Hobbes strips now appear in color print when available, instead of black and white as in their first run.

Early books were printed in smaller format in black and white; these were later reproduced in twos in color in the "Treasuries" (Essential, Authoritative, and Indispensable), except for the contents of Attack of the Deranged Mutant Killer Monster Snow Goons. Those Sunday strips were never reprinted in color until the Complete collection was finally published in 2005. Every book since Snow Goons has been printed in a larger format with Sundays in color and weekday and Saturday strips larger than they appeared in most newspapers.

Remaining books do contain some additional content; for instance, The Calvin and Hobbes Lazy Sunday Book contains a long watercolor Spaceman Spiff epic not seen elsewhere until Complete, and The Calvin and Hobbes Tenth Anniversary Book contains much original commentary from Watterson. Calvin and Hobbes: Sunday Pages 1985–1995 contains 36 Sunday strips in color alongside Watterson's original sketches, prepared for an exhibition at The Ohio State University Cartoon Research Library.

An officially licensed children's textbook entitled Teaching with Calvin and Hobbes was published in a limited single print-run in 1993.[6] The book includes various Calvin and Hobbes strips together with lessons and questions to follow, such as, "What do you think the principal meant when he said they had quite a file on Calvin?" (108). The book is rare and increasingly sought by collectors.[55]

Notes

- ^ "Calvin and Hobbes Trivia". Retrieved 2007-05-12.

- ^ a b "Andrews McMeel Press Release". Retrieved 2006-05-03.

- ^ David Astor (November 4 1989). "Watterson and Walker Differ On Comics: "Calvin and Hobbes" creator criticizes today's cartooning while "Beetle Bailey"/"Hi and Lois" creator defends it at meeting". Editor and Publisher. p. 78.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c Paul Dean (May 26 1987). "Calvin and Hobbes Creator Draws On the Simple Life". Los Angeles Times.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "A Concise Guide To All Legitimate (and some not-so-legitimate) Merchandise". Retrieved 2006-03-16.

- ^ a b c Holmen, Linda (1993). Teaching with Calvin and Hobbes. Playground. ISBN 1-878849-15-8.

- ^ Watterson, Bill (1990). "Some thoughts on the real world by one who glimpsed it and fled". Retrieved 2006-03-16.

- ^ Neely Tucker (4 October 2005). "The Tiger Strikes Again". Washington Post. p. C01.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d Andrew Christie (January 1987). "An Interview With Bill Watterson: The creator of Calvin and Hobbes on cartooning, syndicates, Garfield, Charles Schulz, and editors". Honk magazine.

- ^ "NCS Reuben Award winners (1975–present)". National Cartoonists Society.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Watterson (2005), vol. 3, p. 481. Comic originally published 1995-12-31.

- ^ Charles Solomon (2005-10-21). "The Complete Calvin and Hobbes". Day to Day. 3:28.50 minutes in. NPR.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help) “In the final strip, Calvin and Hobbes put aside their conflicts and rode their sled into a snowy forest. They left behind a hole in the comics page that no strip has been able to fill.” - ^ a b c

Richard Samuel West (February 1989). "Interview: Bill Watterson". Comics Journal (127).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ David Astor (December 3 1988). "Watterson Knocks the Shrinking of Comics". Editor and Publisher. p. 40.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Watterson, Bill (1989). "The Cheapening of Comics". PlanetCartoonist. Archived from the original on 2007-02-09. Retrieved 2006-03-16.

- ^ Astor, David (1992-03-07). "Cartoonists discuss 'Calvin' requirement". Editor & Publisher. p. 34. Retrieved 2007-01-19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Watterson, Bill (2001). Calvin and Hobbes: Sunday Pages 1985–1995. p. 15. ISBN 0-7407-2135-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c "Fans From Around the World Interview Bill Watterson". Andrews McMeel. 2005. Retrieved 2006-03-16.

- ^ Watterson (1995), p. 11

- ^ a b c d e f g Watterson, Bill (1995). The Calvin and Hobbes Tenth Anniversary Book. Andrews McMeel. ISBN 0-8362-0438-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Watterson, Bill (2001). Calvin and Hobbes Sunday Pages 1985–1995. Andrews McMeel. ISBN 0-7407-2135-6.

- ^ Watterson, Bill (1995). Calvin and Hobbes Tenth Anniversary Book. Andrews and McMeel. p. 21. ISBN 0-8362-0438-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Williams, Gene (1987). Watterson: Calvin's other alter ego.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Watterson, Bill (1995). Calvin and Hobbes Tenth Anniversary Book. Andrews and McMeel. p. 22. ISBN 0-8362-0438-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Bill Watterson. "Cast of Characters". The Complete Calvin and Hobbes (press release). Andrew McMeel. Retrieved 2006-03-19.

- ^ Watterson (2005), vol. 3, p. 164. Comic originally published 1993-04-04

- ^ Watterson (2005), vol. 3, p. 400. Comic originally published 1995-06-30.

- ^ Watterson (2005), vol. 1, pp. 248–251. Comics originally published 1987-03-23 to 1987-04-03.

- ^ Watterson (2005), vol. 1, p. 391. Comic originally published 1988-02-08.

- ^ Watterson (2005), vol. 2, pp. 224–232. Comics originally published 1990-01-08 to 1990-02-01.

- ^ Watterson (2005), vol. 2, pp. 422–426. Comics originally published 1991-03-18 to 1991-04-03.

- ^ Watterson (2005), vol. 1, pp. 319–322. Comics originally published 1987-08-31 to 1987-09-11.

- ^ Watterson (2005), vol. 2, pp. 305–309}} Comics originally published 1990-06-25 to 1990-07-07.

- ^ Watterson (2005), vol. 3, pp. 17–22. Comics originally published 1992-05-20 to 1992-06-06.

- ^ Watterson (2005), vol. 3, pp. 261–266. Comics originally published 1993-11-15 to 1993-12-04.

- ^ Watterson (2005), vol. 3, pp. 356–359. Comics originally published 1995-03-20 to 1995-04-01.

- ^ Watterson (2005), vol. 3, p. 432. Comic originally published 1995-09-11.

- ^ a b Watterson (2005), vol. 2, pp. 268–273. Comics originally published 1990-04-16 to 1990-05-05.

- ^ a b Watterson (2005), vol. 3, pp. 430–433. Comics originally published 1995-09-04 to 1995-09-16.

- ^ Watterson (2005), vol. 3, p. 438. Comic originally published 1995-09-24.

- ^ Watterson (2005), vol. 2, p. 292. Comic originally published 1990-05-27.

- ^ Watterson (2005), vol. 2, pp. 292, 336. Comics originally published 1990-05-27 and 1990-08-26.

- ^ Watterson (2005), vol. 2, pp. 273, 292, 336, 429; vol 3, pp. 430–433, 438. Comics originally published 1990-05-05, 1990-05-27, 1990-08-26, 1991-03-31, 1995-09-04 to 1995-09-16, and 1995-09-24.

- ^ Watterson (1995), p. 129.

- ^ a b Watterson (1995), p. 104.

- ^ Watterson (2005), vol. 2, pp. 233, 325. Comics originally published 1990-01-07 and 1990-08-10.

- ^ Watterson (2005), vol. 1, pp. 26, 56, 217; vol. 2, pp. 120, 237, 267, 298, 443; vol 3, pp. 16, 170, 224, 326, 414. Comics originally published 1985-11-30, 1986-02-07, 1987-01-11, 1989-05-28, 1990-02-04, 1990-04-15, 1990-06-10, 1992-02-02, 1992-05-17, 1993-04-18, 1993-08-22, 1995-01-14, and 1995-07-30.

- ^ Watterson (2005), vol. 2, p. 373. Comic originally published 1990-12-01.

- ^ Watterson, Bill (1993). The Days are Just Packed. Andrews McMeel. ISBN 0-8362-1769-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Watterson (2005), vol. 1, p. 215; vol. 2, p. 33.

- ^ Watterson (1995), p. 43.

- ^ Watterson, Bill (1990). Weirdos from Another Planet!. Kansas City, MO: Andrews and McMeel. pp. p. 125. ISBN 0-8362-1862-0.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ "Calvin and Hobbes - We're Back!". Universal Press Syndicate. September 4 2005. Retrieved 2006-03-17.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ David Astor (May 20 2005). "Calvin and Hobbes Returning to Newspapers — Sort Of". Editor and Publisher.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Teaching with Calvin and Hobbes: Information Regarding The Book". Retrieved 2007-03-23.

References

- Watterson, Bill (1995). The Calvin and Hobbes Tenth Anniversary Book. Kansas City, MO: Andrews and McMeel. ISBN 0-8362-0438-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Watterson, Bill (2005). The Complete Calvin and Hobbes. Kansas City, MO: Andrews McMeel Publishing. ISBN 0-7407-4847-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

External links

Template:Illustrated Wikipedia

Official sites

- CalvinAndHobbes.com: The Official Calvin and Hobbes site at GoComics

- Official Calvin and Hobbes Publicity site at Andrews McMeel Publishing

Fan sites

Multimedia

- "Radio show in which fans of the comic strip express their views about the ending of Calvin and Hobbes" (mp3). CBC Canada. 1995.

- "Review of The Complete Calvin and Hobbes featuring an interview with Bill Watterson's editor Lee Salem" (Real, Windows Media). NPR. 2005.

- "In Search of Bill Watterson: A podcast interview with Bill Watterson's mother" (mp3). Jawbone Radio. 2005.

Further reading

- Chris Suellentrop (November 7, 2005). "The last great newspaper comic strip". Slate magazine.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - James Renner (November 26, 2003). "Missing! Calvin and Hobbes creator Bill Watterson". Cleveland Scene.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Neely Tucker (October 4, 2005). "The Tiger Strikes Again". The Washington Post.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)