Mundillo: Difference between revisions

Mmangan333 (talk | contribs) Added the statue of a woman working lace |

Mmangan333 (talk | contribs) American arts award recipient added |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Handmade bobbin lace, tradition and cultural heritage of Puerto Rico and Panama}} |

Bobbin lace made in Puerto Rico{{Short description|Handmade bobbin lace, tradition and cultural heritage of Puerto Rico and Panama}} |

||

[[File:Mundillo de Moca.jpg|thumb|Mundillo de Moca]] |

[[File:Mundillo de Moca.jpg|thumb|Mundillo de Moca]] |

||

[[File:Mundillo 1920.jpg|thumb|Women in Puerto Rico making Mundillo lace, 1920]] |

[[File:Mundillo 1920.jpg|thumb|Women in Puerto Rico making Mundillo lace, 1920]] |

||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

In the 20th century, lacemaking became an important economic activity by women of the island. Prior to WWII, lace provided income for many families to supplement the wages of men who had traveled off-island for work.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last1=Santiago de Curet |first1=Annie |title=Revivals! Diverse Traditions 1920-1945 {{!}} The History of Twentieth-Century American Craft |last2=Kingsley |first2=April |publisher=Harry N. Abrams, Inc. with the American Craft Museum |year=1994 |isbn=0810919559 |editor-last=Kardon |editor-first=Janet |pages=94–95 |language=English |chapter=Puerto Rican Lacemaking: A Persistent Tradition}}</ref> A revival of the tradition in the 1960s and 1970s engaged a new generation of lacemakers.<ref name="Fernandez-Sacco 2020 p. 93">{{cite journal | last=Fernandez-Sacco | first=Ellen | title=Bound to History: Leoncia Lasalle's Slave Narrative from Moca, Puerto Rico, 1945 | journal=Genealogy | publisher=MDPI AG | volume=4 | issue=3 | date=September 11, 2020 | issn=2313-5778 | doi=10.3390/genealogy4030093 | page=93 | doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name=":0" /> In the 1990s, it was reported that 300 people were practitioners of mundillo on the island of Puerto Rico.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Goldstein |first=Elaine Dann |date=1993-01-03 |title=Fine Mundillo Lace From Puerto Rico |pages=6 |work=New York Times |url=https://www.proquest.com/docview/109236295 |access-date=2023-02-24|id={{ProQuest|109236295}} }}</ref> |

In the 20th century, lacemaking became an important economic activity by women of the island. Prior to WWII, lace provided income for many families to supplement the wages of men who had traveled off-island for work.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last1=Santiago de Curet |first1=Annie |title=Revivals! Diverse Traditions 1920-1945 {{!}} The History of Twentieth-Century American Craft |last2=Kingsley |first2=April |publisher=Harry N. Abrams, Inc. with the American Craft Museum |year=1994 |isbn=0810919559 |editor-last=Kardon |editor-first=Janet |pages=94–95 |language=English |chapter=Puerto Rican Lacemaking: A Persistent Tradition}}</ref> A revival of the tradition in the 1960s and 1970s engaged a new generation of lacemakers.<ref name="Fernandez-Sacco 2020 p. 93">{{cite journal | last=Fernandez-Sacco | first=Ellen | title=Bound to History: Leoncia Lasalle's Slave Narrative from Moca, Puerto Rico, 1945 | journal=Genealogy | publisher=MDPI AG | volume=4 | issue=3 | date=September 11, 2020 | issn=2313-5778 | doi=10.3390/genealogy4030093 | page=93 | doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name=":0" /> In the 1990s, it was reported that 300 people were practitioners of mundillo on the island of Puerto Rico.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Goldstein |first=Elaine Dann |date=1993-01-03 |title=Fine Mundillo Lace From Puerto Rico |pages=6 |work=New York Times |url=https://www.proquest.com/docview/109236295 |access-date=2023-02-24|id={{ProQuest|109236295}} }}</ref> |

||

In 2023, [[Rosa Elena Egipciaco]] was awarded a [[National Endowment for the Arts]] Fellowship for her work on preserving, designing, and teaching the lace tradition.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Rosa Elena Egipciaco |url=https://www.arts.gov/honors/heritage/rosa-elena-egipciaco |access-date=2024-12-09 |website=www.arts.gov |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

In Moca, commonly known as the Capital or cradle of Mundillo,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://pr.gov/Directorios/Pages/DirectoriodeMunicipios.aspx|title=Directorio de Municipios de Puerto Rico|website=PR GOV}}</ref> there is an annual festival dedicated to the handmade lace as well as a museum, El Museo Del Mundillo.<ref name="NYT 2009">{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/25/travel/25puerto-rico.html|title=Affordable Caribbean: Puerto Rico|first=John|last=Haskins|work=The New York Times |date=January 22, 2009|via=NYTimes.com}}</ref> |

In Moca, commonly known as the Capital or cradle of Mundillo,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://pr.gov/Directorios/Pages/DirectoriodeMunicipios.aspx|title=Directorio de Municipios de Puerto Rico|website=PR GOV}}</ref> there is an annual festival dedicated to the handmade lace as well as a museum, El Museo Del Mundillo.<ref name="NYT 2009">{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/25/travel/25puerto-rico.html|title=Affordable Caribbean: Puerto Rico|first=John|last=Haskins|work=The New York Times |date=January 22, 2009|via=NYTimes.com}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 00:02, 9 December 2024

Bobbin lace made in Puerto Rico

Mundillo is a craft of handmade bobbin lace that is cultivated and honored on the island of Puerto Rico and Panama.[1]

Description

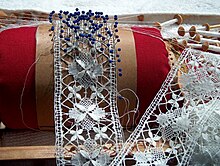

The term 'mundillo' means 'little world', referring to the cylindrical pillow on which the lace maker ('Mundillista') weaves intricate designs. The decorative lace is created using wooden bobbins about the diameter of a pencil, which are wound with thread that is twisted and crossed to form a pattern. Depending on the pattern, as few as two dozen or as many as several hundred bobbins may be used.

In addition to its use as edging and borders on tablecloths and handkerchiefs, and for traditional shirt collars and trim, mundillo is also used to decorate items for special occasions, such as wedding dresses, baptismal gowns, and the cloths used to adorn religious icons. It is said that it was once common for lovers to exchange mundillo lace with romantic inscriptions.[2]

Bobbin lace was brought to Puerto Rico from Spain,[3] where it had thrived in major commercial markets as well as a cottage industry in Galicia, Castilla, and Catalonia. In Spain, lace is called encaje, because it was worked on separately and then joined to material (the Spanish word for "join" is encajar).

In the 20th century, lacemaking became an important economic activity by women of the island. Prior to WWII, lace provided income for many families to supplement the wages of men who had traveled off-island for work.[4] A revival of the tradition in the 1960s and 1970s engaged a new generation of lacemakers.[5][4] In the 1990s, it was reported that 300 people were practitioners of mundillo on the island of Puerto Rico.[6]

In 2023, Rosa Elena Egipciaco was awarded a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship for her work on preserving, designing, and teaching the lace tradition.[7]

In Moca, commonly known as the Capital or cradle of Mundillo,[8] there is an annual festival dedicated to the handmade lace as well as a museum, El Museo Del Mundillo.[9]

Mundillo is celebrated and featured in festivals around the island.[10] A workshop with kits to help train newcomers to mundillo was offered in Morovis in 2018.[11]

In 2021, 95-year-old "mundillera" artisan Nellie Vera Sánchez[12] was awarded a National Heritage Fellowship Award by the National Endowment for the Arts in honor of her work on this traditional craft.[13]

See also

References

- ^ Panamá, GESE-La Estrella de. "El arte de tejer el mundillo". La Estrella de Panamá.

- ^ Martinez, Elena (Fall–Winter 2003). "The Queen of Mundillo". Voices: The Journal of New York Folklore. 29. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ "encajes". Vimeo.

- ^ a b Santiago de Curet, Annie; Kingsley, April (1994). "Puerto Rican Lacemaking: A Persistent Tradition". In Kardon, Janet (ed.). Revivals! Diverse Traditions 1920-1945 | The History of Twentieth-Century American Craft. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. with the American Craft Museum. pp. 94–95. ISBN 0810919559.

- ^ Fernandez-Sacco, Ellen (September 11, 2020). "Bound to History: Leoncia Lasalle's Slave Narrative from Moca, Puerto Rico, 1945". Genealogy. 4 (3). MDPI AG: 93. doi:10.3390/genealogy4030093. ISSN 2313-5778.

- ^ Goldstein, Elaine Dann (1993-01-03). "Fine Mundillo Lace From Puerto Rico". New York Times. p. 6. ProQuest 109236295. Retrieved 2023-02-24.

- ^ "Rosa Elena Egipciaco". www.arts.gov. Retrieved 2024-12-09.

- ^ "Directorio de Municipios de Puerto Rico". PR GOV.

- ^ Haskins, John (January 22, 2009). "Affordable Caribbean: Puerto Rico". The New York Times – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Journal, Newsroom, The Weekly (11 December 2019). "Old San Juan Artisan Fair to Showcase Local Handmade Crafts". The Weekly Journal.

{{cite web}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Morovis celebrará Primer Festival del Tejido Moroveño". El Vocero de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). 19 May 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ "Crónicas 90". Archivo Virtual del Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña. 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ The Weekly Journal, Newsroom (15 June 2021). "Puerto Rican Artisan Wins the National Hispanic Fellowship Award". Retrieved 16 June 2021.

{{cite news}}:|first=has generic name (help)

Further reading

- Méndez, A.H. (1993). Historia y desarrollo del mundillo mocano (in Spanish). A. Hernández Méndez.