Austronesian languages: Difference between revisions

Austronesier (talk | contribs) Not necessary Tag: Reverted |

Offends people’s of Madagascar and Taiwan Tags: Reverted Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Language family |

{{Short description|Language family}} |

||

{{Distinguish|Austroasiatic languages}} |

{{Distinguish|Austroasiatic languages}} |

||

{{Infobox language family |

{{Infobox language family |

||

Revision as of 09:25, 18 August 2024

| Austronesian | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Taiwan, Maritime Southeast Asia, Madagascar, parts of Mainland Southeast Asia, Hainan (China), and Oceania (Polynesia, Micronesia, Melanesia, New Guinea) |

| Ethnicity | Austronesian peoples |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families |

| Proto-language | Proto-Austronesian |

| Subdivisions | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | map |

| Glottolog | aust1307 |

The historical distribution of Austronesian languages | |

The Austronesian languages (pron:/ˌɔːstrəˈniːʒən/ AW-strə-NEE-zhən) are a language family widely spoken throughout Maritime Southeast Asia, parts of Mainland Southeast Asia, Madagascar, the islands of the Pacific Ocean and Taiwan (by Taiwanese indigenous peoples).[1] They are spoken by about 328 million people (4.4% of the world population).[2][3] This makes it the fifth-largest language family by number of speakers. Major Austronesian languages include Malay (around 250–270 million in Indonesia alone in its own literary standard named "Indonesian"),[4] Javanese, Sundanese, Tagalog (standardized as Filipino[5]), Malagasy and Cebuano. According to some estimates, the family contains 1,257 languages, which is the second most of any language family.[6]

In 1706, the Dutch scholar Adriaan Reland first observed similarities between the languages spoken in the Malay Archipelago and by peoples on islands in the Pacific Ocean.[7] In the 19th century, researchers (e.g. Wilhelm von Humboldt, Herman van der Tuuk) started to apply the comparative method to the Austronesian languages. The first extensive study on the history of the phonology was made by the German linguist Otto Dempwolff.[8] It included a reconstruction of the Proto-Austronesian lexicon. The term Austronesian was coined (as German austronesisch) by Wilhelm Schmidt, deriving it from Latin auster "south" and Ancient Greek νῆσος (nêsos "island").[9]

Most Austronesian languages are spoken by island dwellers. Only a few languages, such as Malay and the Chamic languages, are indigenous to mainland Asia. Many Austronesian languages have very few speakers, but the major Austronesian languages are spoken by tens of millions of people. For example, Indonesian is spoken by around 197.7 million people. This makes it the eleventh most-spoken language in the world. Approximately twenty Austronesian languages are official in their respective countries (see the list of major and official Austronesian languages).

By the number of languages they include, Austronesian and Niger–Congo are the two largest language families in the world. They each contain roughly one-fifth of the world's languages. The geographical span of Austronesian was the largest of any language family in the first half of the second millennium CE, before the spread of Indo-European in the colonial period. It ranged from Madagascar off the southeastern coast of Africa to Easter Island in the eastern Pacific. Hawaiian, Rapa Nui, Māori, and Malagasy (spoken on Madagascar) are the geographic outliers.

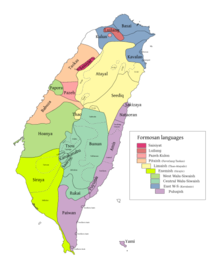

According to Robert Blust (1999), Austronesian is divided into several primary branches, all but one of which are found exclusively in Taiwan. The Formosan languages of Taiwan are grouped into as many as nine first-order subgroups of Austronesian. All Austronesian languages spoken outside the Taiwan mainland (including its offshore Yami language) belong to the Malayo-Polynesian (sometimes called Extra-Formosan) branch.

Most Austronesian languages lack a long history of written attestation. This makes reconstructing earlier stages—up to distant Proto-Austronesian—all the more remarkable. The oldest inscription in the Cham language, the Đông Yên Châu inscription dated to c. 350 AD, is the first attestation of any Austronesian language.

Typological characteristics

Phonology

The Austronesian languages overall possess phoneme inventories which are smaller than the world average. Around 90% of the Austronesian languages have inventories of 19–25 sounds (15–20 consonants and 4–5 vowels), thus lying at the lower end of the global typical range of 20–37 sounds. However, extreme inventories are also found, such as Nemi (New Caledonia) with 43 consonants.[10]

The canonical root type in Proto-Austronesian is disyllabic with the shape CV(C)CVC (C = consonant; V = vowel), and is still found in many Austronesian languages.[11] In most languages, consonant clusters are only allowed in medial position, and often, there are restrictions for the first element of the cluster.[12] There is a common drift to reduce the number of consonants which can appear in final position, e.g. Buginese, which only allows the two consonants /ŋ/ and /ʔ/ as finals, out of a total number of 18 consonants. Complete absence of final consonants is observed e.g. in Nias, Malagasy and many Oceanic languages.[13]

Tonal contrasts are rare in Austronesian languages,[14] although Moklen and a few languages of the Chamic, South Halmahera–West New Guinea and New Caledonian subgroups do show lexical tone.[15]

Morphology

Most Austronesian languages are agglutinative languages with a relatively high number of affixes, and clear morpheme boundaries.[16] Most affixes are prefixes (Malay and Indonesian ber-jalan 'walk' < jalan 'road'), with a smaller number of suffixes (Tagalog titis-án 'ashtray' < títis 'ash') and infixes (Roviana t<in>avete 'work (noun)' < tavete 'work (verb)').[17]

Reduplication is commonly employed in Austronesian languages. This includes full reduplication (Malay and Indonesian anak-anak 'children' < anak 'child'; Karo Batak nipe-nipe 'caterpillar' < nipe 'snake') or partial reduplication (Agta taktakki 'legs' < takki 'leg', at-atu 'puppy' < atu 'dog').[18]

Syntax

It is difficult to make generalizations about the languages that make up a family as diverse as Austronesian. Very broadly, one can divide the Austronesian languages into three groups: Philippine-type languages, Indonesian-type languages and post-Indonesian type languages:[19]

- The first group includes, besides the languages of the Philippines, the Austronesian languages of Taiwan, Sabah, North Sulawesi and Madagascar. It is primarily characterized by the retention of the original system of Philippine-type voice alternations, where typically three or four verb voices determine which semantic role the "subject"/"topic" expresses (it may express either the actor, the patient, the location and the beneficiary, or various other circumstantial roles such as instrument and concomitant). The phenomenon has frequently been referred to as focus (not to be confused with the usual sense of that term in linguistics). Furthermore, the choice of voice is influenced by the definiteness of the participants. The word order has a strong tendency to be verb-initial.

- In contrast, the more innovative Indonesian-type languages, which are particularly represented in Malaysia and western Indonesia, have reduced the voice system to a contrast between only two voices (actor voice and "undergoer" voice), but these are supplemented by applicative morphological devices (originally two: the more direct *-i and more oblique *-an/-[a]kən), which serve to modify the semantic role of the "undergoer". They are also characterized by the presence of preposed clitic pronouns. Unlike the Philippine type, these languages mostly tend towards verb-second word-orders. A number of languages, such as the Batak languages, Old Javanese, Balinese, Sasak and several Sulawesi languages seem to represent an intermediate stage between these two types.[20][21]

- Finally, in some languages, which Ross calls "post-Indonesian", the original voice system has broken down completely and the voice-marking affixes no longer preserve their functions.

Lexicon

The Austronesian language family has been established by the linguistic comparative method on the basis of cognate sets, sets of words from multiple languages, which are similar in sound and meaning which can be shown to be descended from the same ancestral word in Proto-Austronesian according to regular rules. Some cognate sets are very stable. The word for eye in many Austronesian languages is mata (from the most northerly Austronesian languages, Formosan languages such as Bunun and Amis all the way south to Māori).[22]

Other words are harder to reconstruct. The word for two is also stable, in that it appears over the entire range of the Austronesian family, but the forms (e.g. Bunun dusa; Amis tusa; Māori rua) require some linguistic expertise to recognise. The Austronesian Basic Vocabulary Database gives word lists (coded for cognateness) for approximately 1000 Austronesian languages.[22]

Classification

The internal structure of the Austronesian languages is complex. The family consists of many similar and closely related languages with large numbers of dialect continua, making it difficult to recognize boundaries between branches. The first major step towards high-order subgrouping was Dempwolff's recognition of the Oceanic subgroup (called Melanesisch by Dempwolff).[8] The special position of the languages of Taiwan was first recognized by André-Georges Haudricourt (1965),[23] who divided the Austronesian languages into three subgroups: Northern Austronesian (= Formosan), Eastern Austronesian (= Oceanic), and Western Austronesian (all remaining languages).

In a study that represents the first lexicostatistical classification of the Austronesian languages, Isidore Dyen (1965) presented a radically different subgrouping scheme.[24] He posited 40 first-order subgroups, with the highest degree of diversity found in the area of Melanesia. The Oceanic languages are not recognized, but are distributed over more than 30 of his proposed first-order subgroups. Dyen's classification was widely criticized and for the most part rejected,[25] but several of his lower-order subgroups are still accepted (e.g. the Cordilleran languages, the Bilic languages or the Murutic languages).

Subsequently, the position of the Formosan languages as the most archaic group of Austronesian languages was recognized by Otto Christian Dahl (1973),[26] followed by proposals from other scholars that the Formosan languages actually make up more than one first-order subgroup of Austronesian. Robert Blust (1977) first presented the subgrouping model which is currently accepted by virtually all scholars in the field,[27] with more than one first-order subgroup on Taiwan, and a single first-order branch encompassing all Austronesian languages spoken outside of Taiwan, viz. Malayo-Polynesian. The relationships of the Formosan languages to each other and the internal structure of Malayo-Polynesian continue to be debated.

Primary branches on Taiwan (Formosan languages)

In addition to Malayo-Polynesian, thirteen Formosan subgroups are broadly accepted. The seminal article in the classification of Formosan—and, by extension, the top-level structure of Austronesian—is Blust (1999). Prominent Formosanists (linguists who specialize in Formosan languages) take issue with some of its details, but it remains the point of reference for current linguistic analyses. Debate centers primarily around the relationships between these families. Of the classifications presented here, Blust (1999) links two families into a Western Plains group, two more in a Northwestern Formosan group, and three into an Eastern Formosan group, while Li (2008) also links five families into a Northern Formosan group. Harvey (1982), Chang (2006) and Ross (2012) split Tsouic, and Blust (2013) agrees the group is probably not valid.

Other studies have presented phonological evidence for a reduced Paiwanic family of Paiwanic, Puyuma, Bunun, Amis, and Malayo-Polynesian, but this is not reflected in vocabulary. The Eastern Formosan peoples Basay, Kavalan, and Amis share a homeland motif that has them coming originally from an island called Sinasay or Sanasay.[28] The Amis, in particular, maintain that they came from the east, and were treated by the Puyuma, amongst whom they settled, as a subservient group.[29]

Blust (1999)

- Formosan

- Western Plains

- Thao language a.k.a. Sao: Brawbaw and Shtafari dialects

- Central Western Plains

- Babuza language; old Favorlang language: Taokas and Poavosa dialects

- Papora-Hoanya language: Papora, Hoanya dialects

- Northwest Formosan

- Saisiyat language: Taai and Tungho dialects

- Pazeh language and Kulun

-

- Atayal language

- Seediq language a.k.a. Truku/Taroko

-

- Northern (Kavalanic languages)

- Basay language: Trobiawa and Linaw–Qauqaut dialects

- Kavalan language

- Ketagalan language, or Ketangalan

- Central (Ami)

- Siraya language

- Northern (Kavalanic languages)

-

- Mantauran, Tona, and Maga dialects of Rukai are divergent

- Paiwan language (south-eastern tip of Formosa)

- (outside Formosa)

Li (2008)

This classification retains Blust's East Formosan, and unites the other northern languages. Li (2008) proposes a Proto-Formosan (F0) ancestor and equates it with Proto-Austronesian (PAN), following the model in Starosta (1995).[30] Rukai and Tsouic are seen as highly divergent, although the position of Rukai is highly controversial.[31]

Sagart (2004, 2021)

Sagart (2004) proposes that the numerals of the Formosan languages reflect a nested series of innovations, from languages in the northwest (near the putative landfall of the Austronesian migration from the mainland), which share only the numerals 1–4 with proto-Malayo-Polynesian, counter-clockwise to the eastern languages (purple on map), which share all numerals 1–10. Sagart (2021) finds other shared innovations that follow the same pattern. He proposes that pMP *lima 'five' is a lexical replacement (from 'hand'), and that pMP *pitu 'seven', *walu 'eight' and *Siwa 'nine' are contractions of pAN *RaCep 'five', a ligature *a or *i 'and', and *duSa 'two', *telu 'three', *Sepat 'four', an analogical pattern historically attested from Pazeh. The fact that the Kradai languages share the numeral system (and other lexical innovations) of pMP suggests that they are a coordinate branch with Malayo-Polynesian, rather than a sister family to Austronesian.[32][33]

Sagart's resulting classification is:[34]

- Austronesian (pAN ca. 5200 BP)

- Pituish

(pAN *RaCepituSa 'five-and-two' truncated to *pitu 'seven'; *sa-ŋ-aCu 'nine' [lit. one taken away])- Limaish

(pAN *RaCep 'five' replaced by *lima 'hand'; *Ca~ reduplication to form the series of numerals for counting humans)- Enemish

(additive 'five-and-one' or 'twice-three' replaced by reduplicated *Nem-Nem > *emnem [*Nem 'three' is reflected in Basay, Siraya and Makatao]; pAN *kawaS 'year, sky' replaced by *CawiN)- Walu-Siwaish

(*walu 'eight' and *Siwa 'nine' from *RaCepat(e)lu 'five-and-three' and *RaCepiSepat 'five-and-four')- Central WS

(pAN *isa etc. 'one' replaced by *Ca~CiNi (reduplication of 'alone') in the human-counting series; pAN *iCit 'ten' replaced by *ma-sa-N 'one times'.) - East WS (pEWS ca. 4500 BP)

(innovations *baCaq-an 'ten'; *nanum 'water' alongside pAN *daNum)- Puluqish

(innovative *sa-puluq 'ten', from *sa- 'one' + 'separate, set aside'; use of prefixes *paka- and *maka- to mark abilitative)- Northern: Ami–Puyuma

(*sasay 'one'; *mukeCep 'ten' for the human and non-human series; *ukak 'bone', *kuCem 'cloud') - Paiwan

- Southern Austronesian (pSAN ca. 4000 BP)

(linker *atu 'and' > *at after *sa-puluq in numerals 11–19; lexical innovations such as *baqbaq 'mouth', *qa-sáuŋ 'canine tooth', *qi(d)zúR 'saliva', *píntu 'door', *-ŋel 'deaf')

- Northern: Ami–Puyuma

Malayo-Polynesian

The Malayo-Polynesian languages are—among other things—characterized by certain sound changes, such as the mergers of Proto-Austronesian (PAN) *t/*C to Proto-Malayo-Polynesian (PMP) *t, and PAN *n/*N to PMP *n, and the shift of PAN *S to PMP *h.[35]

There appear to have been two great migrations of Austronesian languages that quickly covered large areas, resulting in multiple local groups with little large-scale structure. The first was Malayo-Polynesian, distributed across the Philippines, Indonesia, and Melanesia. The second migration was that of the Oceanic languages into Polynesia and Micronesia.[36]

Major languages

History

From the standpoint of historical linguistics, the place of origin (in linguistic terminology, Urheimat) of the Austronesian languages (Proto-Austronesian language) is most likely the main island of Taiwan, also known as Formosa; on this island the deepest divisions in Austronesian are found along small geographic distances, among the families of the native Formosan languages.

According to Robert Blust, the Formosan languages form nine of the ten primary branches of the Austronesian language family.[37] Comrie (2001:28) noted this when he wrote:

... the internal diversity among the... Formosan languages... is greater than that in all the rest of Austronesian put together, so there is a major genetic split within Austronesian between Formosan and the rest... Indeed, the genetic diversity within Formosan is so great that it may well consist of several primary branches of the overall Austronesian family.

At least since Sapir (1968), writing in 1949, linguists have generally accepted that the chronology of the dispersal of languages within a given language family can be traced from the area of greatest linguistic variety to that of the least. For example, English in North America has large numbers of speakers, but relatively low dialectal diversity, while English in Great Britain has much higher diversity; such low linguistic variety by Sapir's thesis suggests a more recent spread of English in North America. While some scholars suspect that the number of principal branches among the Formosan languages may be somewhat less than Blust's estimate of nine (e.g. Li 2006), there is little contention among linguists with this analysis and the resulting view of the origin and direction of the migration. For a recent dissenting analysis, see Peiros (2004).

The protohistory of the Austronesian people can be traced farther back through time. To get an idea of the original homeland of the populations ancestral to the Austronesian peoples (as opposed to strictly linguistic arguments), evidence from archaeology and population genetics may be adduced. Studies from the science of genetics have produced conflicting outcomes. Some researchers find evidence for a proto-Austronesian homeland on the Asian mainland (e.g., Melton et al. 1998), while others mirror the linguistic research, rejecting an East Asian origin in favor of Taiwan (e.g., Trejaut et al. 2005). Archaeological evidence (e.g., Bellwood 1997) is more consistent, suggesting that the ancestors of the Austronesians spread from the South Chinese mainland to Taiwan at some time around 8,000 years ago.

Evidence from historical linguistics suggests that it is from this island that seafaring peoples migrated, perhaps in distinct waves separated by millennia, to the entire region encompassed by the Austronesian languages.[38] It is believed that this migration began around 6,000 years ago.[39] However, evidence from historical linguistics cannot bridge the gap between those two periods. The view that linguistic evidence connects Austronesian languages to the Sino-Tibetan ones, as proposed for example by Sagart (2002), is a minority one. As Fox (2004:8) states:

Implied in... discussions of subgrouping [of Austronesian languages] is a broad consensus that the homeland of the Austronesians was in Taiwan. This homeland area may have also included the P'eng-hu (Pescadores) islands between Taiwan and China and possibly even sites on the coast of mainland China, especially if one were to view the early Austronesians as a population of related dialect communities living in scattered coastal settlements.

Linguistic analysis of the Proto-Austronesian language stops at the western shores of Taiwan; any related mainland language(s) have not survived. The only exceptions, the Chamic languages, derive from more recent migration to the mainland.[40] However, according to Ostapirat's interpretation of the seriously discussed Austro-Tai hypothesis, the Kra–Dai languages (also known as Tai–Kadai) are exactly those related mainland languages.

Hypothesized relations

Genealogical links have been proposed between Austronesian and various families of East and Southeast Asia.

Austro-Tai

An Austro-Tai proposal linking Austronesian and the Kra-Dai languages of the southeastern continental Asian mainland was first proposed by Paul K. Benedict, and is supported by Weera Ostapirat, Roger Blench, and Laurent Sagart, based on the traditional comparative method. Ostapirat (2005) proposes a series of regular correspondences linking the two families and assumes a primary split, with Kra-Dai speakers being the people who stayed behind in their Chinese homeland. Blench (2004) suggests that, if the connection is valid, the relationship is unlikely to be one of two sister families. Rather, he suggests that proto-Kra-Dai speakers were Austronesians who migrated to Hainan Island and back to the mainland from the northern Philippines, and that their distinctiveness results from radical restructuring following contact with Hmong–Mien and Sinitic. An extended version of Austro-Tai was hypothesized by Benedict who added the Japonic languages to the proposal as well.[41]

Austric

A link with the Austroasiatic languages in an 'Austric' phylum is based mostly on typological evidence. However, there is also morphological evidence of a connection between the conservative Nicobarese languages and Austronesian languages of the Philippines.[citation needed] Robert Blust supports the hypothesis which connects the lower Yangtze neolithic Austro-Tai entity with the rice-cultivating Austro-Asiatic cultures, assuming the center of East Asian rice domestication, and putative Austric homeland, to be located in the Yunnan/Burma border area.[42] Under that view, there was an east-west genetic alignment, resulting from a rice-based population expansion, in the southern part of East Asia: Austroasiatic-Kra-Dai-Austronesian, with unrelated Sino-Tibetan occupying a more northerly tier.[42]

Sino-Austronesian

French linguist and Sinologist Laurent Sagart considers the Austronesian languages to be related to the Sino-Tibetan languages, and also groups the Kra–Dai languages as more closely related to the Malayo-Polynesian languages.[43] Sagart argues for a north-south genetic relationship between Chinese and Austronesian, based on sound correspondences in the basic vocabulary and morphological parallels.[42] Laurent Sagart (2017) concludes that the possession of the two kinds of millets[a] in Taiwanese Austronesian languages (not just Setaria, as previously thought) places the pre-Austronesians in northeastern China, adjacent to the probable Sino-Tibetan homeland.[42] Ko et al.'s genetic research (2014) appears to support Laurent Sagart's linguistic proposal, pointing out that the exclusively Austronesian mtDNA E-haplogroup and the largely Sino-Tibetan M9a haplogroup are twin sisters, indicative of an intimate connection between the early Austronesian and Sino-Tibetan maternal gene pools, at least.[44][45] Additionally, results from Wei et al. (2017) are also in agreement with Sagart's proposal, in which their analyses show that the predominantly Austronesian Y-DNA haplogroup O3a2b*-P164(xM134) belongs to a newly defined haplogroup O3a2b2-N6 being widely distributed along the eastern coastal regions of Asia, from Korea to Vietnam.[46] Sagart also groups the Austronesian languages in a recursive-like fashion, placing Kra-Dai as a sister branch of Malayo-Polynesian. His methodology has been found to be spurious by his peers.[47][48]

Japanese

Several linguists have proposed that Japanese is genetically related to the Austronesian family, cf. Benedict (1990), Matsumoto (1975), Miller (1967).

Some other linguists think it is more plausible that Japanese is not genetically related to the Austronesian languages, but instead was influenced by an Austronesian substratum or adstratum.

Those who propose this scenario suggest that the Austronesian family once covered the islands to the north as well as to the south. Martine Robbeets (2017)[49] claims that Japanese genetically belongs to the "Transeurasian" (= Macro-Altaic) languages, but underwent lexical influence from "para-Austronesian", a presumed sister language of Proto-Austronesian.

The linguist Ann Kumar (2009) proposed that some Austronesians might have migrated to Japan, possibly an elite-group from Java, and created the Japanese-hierarchical society. She also identifies 82 possible cognates between Austronesian and Japanese, however her theory remains very controversial.[50] The linguist Asha Pereltsvaig criticized Kumar's theory on several points.[51] The archaeological problem with that theory is that, contrary to the claim that there was no rice farming in China and Korea in prehistoric times, excavations have indicated that rice farming has been practiced in this area since at least 5000 BC.[51] There are also genetic problems. The pre-Yayoi Japanese lineage was not shared with Southeast Asians, but was shared with Northwest Chinese, Tibetans and Central Asians.[51] Linguistic problems were also pointed out. Kumar did not claim that Japanese was an Austronesian language derived from proto-Javanese language, but only that it provided a superstratum language for old Japanese, based on 82 plausible Javanese-Japanese cognates, mostly related to rice farming.[51]

East Asian

In 2001, Stanley Starosta proposed a new language family named East Asian, that includes all primary language families in the broader East Asia region except Japonic and Koreanic. This proposed family consists of two branches, Austronesian and Sino-Tibetan-Yangzian, with the Kra-Dai family considered to be a branch of Austronesian, and "Yangzian" to be a new sister branch of Sino-Tibetan consisting of the Austroasiatic and Hmong-Mien languages.[52] This proposal was further researched on by linguists such as Michael D. Larish in 2006, who also included the Japonic and Koreanic languages in the macrofamily. The proposal has since been adopted by linguists such as George van Driem, albeit without the inclusion of Japonic and Koreanic.[53]

Ongan

Blevins (2007) proposed that the Austronesian and the Ongan protolanguage are the descendants of an Austronesian–Ongan protolanguage.[54] This view is not supported by mainstream linguists and remains very controversial. Robert Blust rejects Blevins' proposal as far-fetched and based solely on chance resemblances and methodologically flawed comparisons.[55]

Writing systems

Most Austronesian languages have Latin-based writing systems today. Some non-Latin-based writing systems are listed below.

- Brahmi script

- Kawi script

- Balinese alphabet – used to write Balinese, Kawi, Malay, Sasak, and Sanskrit.

- Batak alphabet – used to write several Batak languages.

- Baybayin – used to write Tagalog and several Philippine languages.

- Bima alphabet – once used to write the Bima language.

- Buhid alphabet – used to write Buhid language.

- Hanunó'o alphabet – used to write Hanuno'o language.

- Javanese script – used to write the Javanese language and several neighbouring languages like Madurese.

- Kerinci alphabet (Kaganga) – used to write the Kerinci language.

- Kulitan alphabet – used to write the Kapampangan language.

- Lampung alphabet – used to write Lampung and Komering.

- Linggi alphabet – used to write Peninsular Malayic languages.

- Lontara alphabet – used to write the Buginese, Makassarese and several languages of Sulawesi.

- Sundanese script – standardized script based on Old Sundanese script, used to write the Sundanese language.

- Rejang alphabet – used to write the Rejang language.

- Rencong alphabet – once used to write the Malay language.

- Tagbanwa alphabet – once used to write various Palawan languages.

- Lota alphabet – used to write the Ende-Li'o language.

- Cham alphabet – used to write Cham language.

- Kawi script

- Arabic script

- Pegon alphabet – used to write Javanese, Sundanese and Madurese as well as several smaller neighbouring languages.

- Jawi alphabet – used to write Malay, Acehnese, Banjar, Minangkabau, Maguindanao, Tausug, Western Cham and others.

- Sorabe alphabet – once used to write several dialects of Malagasy language.

- Hangul – used to write the Cia-Cia language but the project is no longer active.

- Dunging – used to write the Iban language

- Avoiuli – used to write the Raga language.

- Eskayan – used to write the Eskayan language, a secret language based on Boholano.

- Woleai script (Caroline Island script) – used to write the Carolinian language (Refaluwasch).

- Rongorongo – possibly used to write the Rapa Nui language.

- Gagarit Abada – used to write Dusunic languages but it was not widely used.

- Gangga Melayu – used to write Perak Malay

- Braille – used in Filipino, Malaysian, Indonesian, Tolai, Motu, Māori, Samoan, Malagasy, and many other Austronesian languages.

Comparison charts

Below are two charts comparing list of numbers of 1–10 and thirteen words in Austronesian languages; spoken in Taiwan, the Philippines, the Mariana Islands, Indonesia, Malaysia, Chams or Champa (in Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam), East Timor, Papua, New Zealand, Hawaii, Madagascar, Borneo, Kiribati, Caroline Islands, and Tuvalu.

| Austronesian List of Numbers 1–10 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proto-Austronesian | *əsa *isa |

*duSa | *təlu | *Səpat | *lima | *ənəm | *pitu | *walu | *Siwa | *(sa-)puluq | |||||||||||

| Formosan languages | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||||||||||

| Atayal | qutux | sazing | cyugal | payat | magal | mtzyu / tzyu | mpitu / pitu | mspat / spat | mqeru / qeru | mopuw / mpuw | |||||||||||

| Seediq | kingal | daha | teru | sepac | rima | mmteru | mpitu | mmsepac | mngari | maxal | |||||||||||

| Truku | kingal | dha | tru | spat | rima | mataru | empitu | maspat | mngari | maxal | |||||||||||

| Thao | taha | tusha | turu | shpat | tarima | katuru | pitu | kashpat | tanathu | makthin | |||||||||||

| Papora | tanu | nya | tul | pat | lima | minum | pitu | mehal | mesi | metsi | |||||||||||

| Hoanya | mital | misa | miru | mipal | lima | rom | pito | talo | asia | myataisi | |||||||||||

| Babuza | nata | naroa | natool'a | napat | nahup | natap | natu | maaspat | nataxaxoan | tsihet | |||||||||||

| Favorlang | natta | narroa | natorra | naspat | nachab | nataap | naito | maaspat | tannacho | tschiet | |||||||||||

| Taokas | tatanu | rua | tool'a | lapat | hasap | tahap | yuweto | mahalpat | tanaso | tais'id | |||||||||||

| Pazeh/Kaxabu | adang | dusa | tu'u | supat | xasep | xasebuza | xasebidusa | xasebitu'u | xasebisupat | isit | |||||||||||

| Saisiyat | 'aeihae' | roSa' | to:lo' | Sopat | haseb | SayboSi: | SayboSi: 'aeihae' | maykaSpat | hae'hae' | lampez / langpez | |||||||||||

| Tsou | coni | yuso | tuyu | sʉptʉ | eimo | nomʉ | pitu | voyu | sio | maskʉ | |||||||||||

| Hla'alua | canni | suua | tuulu | paatʉ | kulima | kʉnʉmʉ | kupitu | kualu | kusia | kumaahlʉ | |||||||||||

| Kanakanavu | cani | cusa | turu | sʉʉpatʉ | rima | nʉmʉ | pitu | aru | sia | maan | |||||||||||

| Bunun | tasʔa | dusa | tau | paat | hima | nuum | pitu | vau | siva | masʔan | |||||||||||

| Rukai | itha | drusa | tulru | supate | lrima | eneme | pitu | valru | bangate | pulruku / mangealre | |||||||||||

| Paiwan | ita | drusa | tjelu | sepatj | lima | enem | pitju | alu | siva | tapuluq | |||||||||||

| Puyuma | sa | druwa | telu | pat | lima | unem | pitu | walu | iwa | pulu | |||||||||||

| Kavalan | usiq | uzusa | utulu | uspat | ulima | unem | upitu | uwalu | usiwa | rabtin | |||||||||||

| Basay | tsa | lusa | tsu | səpat | tsjima | anəm | pitu | wasu | siwa | labatan | |||||||||||

| Amis | cecay | tosa | tolo | spat | lima | enem | pito | falo | siwa | pulu' / mo^tep | |||||||||||

| Sakizaya | cacay | tosa | tolo | sepat | lima | enem | pito | walo | siwa | cacay a bataan | |||||||||||

| Siraya | sasaat | duha | turu | tapat | tu-rima | tu-num | pitu | pipa | kuda | keteng | |||||||||||

| Taivoan | tsaha' | ruha | toho | paha' | hima | lom | kito' | kipa' | matuha | kaipien | |||||||||||

| Makatao | na-saad | ra-ruha | ra-ruma | ra-sipat | ra-lima | ra-hurum | ra-pito | ra-haru | ra-siwa | ra-kaitian | |||||||||||

| Qauqaut | ca | lusa | cuu | səpat | cima | anəm | pitu | wacu | siwa | labatan | |||||||||||

| Malayo-Polynesian languages | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||||||||||

| Proto-Malayo-Polynesian | *əsa *isa |

*duha | *təlu | *əpat | *lima | *ənəm | *pitu | *walu | *siwa | *puluq | |||||||||||

| Yami(Tao) | asa | adoa | atlo | apat | alima | anem | apito | awao | asiam | asa ngernan | |||||||||||

| Acehnese | sifar soh |

sa | duwa | lhee | peuet | limong | nam | tujoh | lapan | sikureueng | siploh | ||||||||||

| Balinesea | nul |

siki besik |

kalih dua |

tiga telu |

papat |

lima |

nenem |

pitu |

kutus |

sia |

dasa | ||||||||||

| Banjar | asa | dua | talu | ampat | lima | anam | pitu | walu | sanga | sapuluh | |||||||||||

| Batak, Toba | sada | dua | tolu | opat | lima | onom | pitu | ualu | sia | sampulu | |||||||||||

| Buginese | séddi | dua | tellu | eppa’ | lima | enneng | pitu | arua | aséra | seppulo | |||||||||||

| Cia-Cia | dise ise |

rua ghua |

tolu | pa'a | lima | no'o | picu | walu oalu |

siua | ompulu | |||||||||||

| Cham | sa | dua | klau | pak | lima | nam | tujuh | dalapan | salapan | sapluh | |||||||||||

| Old Javanese[56] | siji sa- |

rwa | tĕlu | pāt | lima | nĕm | pitu | walu | sanga | sapuluh | |||||||||||

| Javanese[57] | nol | siji | loro | telu | papat | lima | enem | pitu | wolu | sanga | sepuluh | ||||||||||

| Kelantan-Pattani | kosong | so | duwo | tigo | pak | limo | ne | tujoh | lape | smile | spuloh | ||||||||||

| Komering | nol | osai | rua | tolu | pak | lima | nom | pitu | walu | suwai | puluh | ||||||||||

| Madurese | nol | settong | dhuwa' | tello' | empa' | lema' | ennem | petto' | ballu' | sanga' | sapolo | ||||||||||

| Makassarese | lobbang nolo' |

se're | rua | tallu | appa' | lima | annang | tuju | sangantuju | salapang | sampulo | ||||||||||

| Indonesian/Malay | kosong sifar[58] nol[59] |

sa/se satu suatu |

dua | tiga | empat | lima | enam | tujuh | delapan lapan[60] |

sembilan | sepuluh | ||||||||||

| Minangkabau | ciek | duo | tigo | ampek | limo | anam | tujuah | salapan | sambilan | sapuluah | |||||||||||

| Moken | cha:? | thuwa:? | teloj (təlɔy) |

pa:t | lema:? | nam | luɟuːk | waloj (walɔy) |

chewaj (cʰɛwaːy / sɛwaːy) |

cepoh | |||||||||||

| Rejang | do | duai | tlau | pat | lêmo | num | tujuak | dêlapên | sêmbilan | sêpuluak | |||||||||||

| Sasak | sekek | due | telo | empat | lime | enam | pituk | baluk | siwak | sepulu | |||||||||||

| Sundanese | nol | hiji | dua | tilu | opat | lima | genep | tujuh | dalapan | salapan | sapuluh | ||||||||||

| Terengganu Malay | kosong | se | duwe | tige | pak | lime | nang | tujoh | lapang | smilang | spuloh | ||||||||||

| Tetun | nol | ida | rua | tolu | hat | lima | nen | hitu | ualu | sia | sanulu | ||||||||||

| Tsat (HuiHui)c | sa˧ * ta˩ ** |

tʰua˩ | kiə˧ | pa˨˦ | ma˧ | naːn˧˨ | su˥ | paːn˧˨ | tʰu˩ paːn˧˨ | piu˥ | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Ilocano | ibbong awan |

maysa | dua | tallo | uppat | lima | innem | pito | walo | siam | sangapulo | ||||||||||

| Ibanag | awan | tadday | duwa | tallu | appa' | lima | annam | pitu | walu | siyam | mafulu | ||||||||||

| Pangasinan | sakey | duwa | talo | apat | lima | anem | pito | walo | siyam | samplo | |||||||||||

| Kapampangan | alá | métung/ isá | adwá | atlú | ápat | limá | ánam | pitú | walú | siám | apúlu | ||||||||||

| Tagalog | walâ | isá | dalawá | tatló | apat | limá | anim | pitó | waló | siyám | sampû | ||||||||||

| Bikol | warâ | sarô | duwá | tuló | apát | limá | anóm | pitó | waló | siyám | sampulò | ||||||||||

| Aklanon | uwa | isaea sambilog |

daywa | tatlo | ap-at | lima | an-om | pito | waeo | siyam | napueo | ||||||||||

| Karay-a | wara | (i)sara | darwa | tatlo | apat | lima | anəm | pito | walo | siyam | napulo | ||||||||||

| Onhan | isya | darwa | tatlo | upat | lima | an-om | pito | walo | siyam | sampulo | |||||||||||

| Romblomanon | isá | duhá | tuyó | upát | limá | onúm | pitó | wayó | siyám | napuyò | |||||||||||

| Masbatenyo | isád usád |

duwá duhá |

tuló | upát | limá | unóm | pitó | waló | siyám | napulò | |||||||||||

| Hiligaynon | walâ | isá | duhá | tatló | apat | limá | anom | pitó | waló | siyám | napulò | ||||||||||

| Cebuano | walâ | usá | duhá | tuló | upát | limá | unóm | pitó | waló | siyám | napulò pulò | ||||||||||

| Waray | waráy | usá | duhá | tuló | upát | limá | unóm | pitó | waló | siyám | napulò | ||||||||||

| Tausug | sipar | isa | duwa | tū | upat | lima | unum | pitu | walu | siyam | hangpu' | ||||||||||

| Maranao | isa | dowa | təlo | pat | lima | nəm | pito | walo | siyaw | sapolo | |||||||||||

| Benuaq (Dayak Benuaq) | eray | duaq | toluu | opaat | limaq | jawatn | turu | walo | sie | sepuluh | |||||||||||

| Lun Bawang/ Lundayeh | na luk dih | eceh | dueh | teluh | epat | limeh | enem | tudu' | waluh | liwa' | pulu' | ||||||||||

| Dusun | aiso | iso | duo | tolu | apat | limo | onom | turu | walu | siam | hopod | ||||||||||

| Malagasy | aotra | isa iray |

roa | telo | efatra | dimy | enina | fito | valo | sivy | folo | ||||||||||

| Sangirese (Sangir-Minahasan) | sembau | darua | tatelu | epa | lima | eneng | pitu | walu | sio | mapulo | |||||||||||

| Biak | bei | oser | suru | kyor | fyak | rim | wonem | fik | war | siw | samfur | ||||||||||

| Oceanic languagesd | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||||||||||

| Chuukese | eet | érúúw | één | fáán | niim | woon | fúús | waan | ttiw | engoon | |||||||||||

| Fijian | saiva | dua | rua | tolu | vaa | lima | ono | vitu | walu | ciwa | tini | ||||||||||

| Gilbertese | akea | teuana | uoua | tenua | aua | nimaua | onoua | itua | wanua | ruaiwa | tebwina | ||||||||||

| Hawaiian | 'ole | 'e-kahi | 'e-lua | 'e-kolu | 'e-hā | 'e-lima | 'e-ono | 'e-hiku | 'e-walu | 'e-iwa | 'umi | ||||||||||

| Māori | kore | tahi | rua | toru | whā | rima | ono | whitu | waru | iwa | tekau ngahuru | ||||||||||

| Marshallese[61] | o̧o | juon | ruo | jilu | emān | ļalem | jiljino | jimjuon | ralitōk | ratimjuon | jon̄oul | ||||||||||

| Motue[62] | ta | rua | toi | hani | ima | tauratoi | hitu | taurahani | taurahani-ta | gwauta | |||||||||||

| Niuean | nakai | taha | ua | tolu | fā | lima | ono | fitu | valu | hiva | hogofulu | ||||||||||

| Rapanui | tahi | rua | toru | hā | rima | ono | hitu | va'u | iva | angahuru | |||||||||||

| Rarotongan Māori | kare | ta'i | rua | toru | 'ā | rima | ono | 'itu | varu | iva | nga'uru | ||||||||||

| Rotuman | ta | rua | folu | hake | lima | ono | hifu | vạlu | siva | saghulu | |||||||||||

| Samoan | o | tasi | lua | tolu | fa | lima | ono | fitu | valu | iva | sefulu | ||||||||||

| Samoan (K-type) |

o | kasi | lua | kolu | fa | lima | ogo | fiku | valu | iva | sefulu | ||||||||||

| Tahitian | hō'ē tahi |

piti | toru | maha | pae | ōno | hitu | va'u | iva | hō'ē 'ahuru | |||||||||||

| Tongan | noa | taha | ua | tolu | fa | nima | ono | fitu | valu | hiva | hongofulu taha noa | ||||||||||

| Tuvaluan | tahi tasi |

lua | tolu | fa | lima | ono | fitu | valu | iva | sefulu | |||||||||||

| Yapese | dæriiy dæriiq |

t’aareeb | l’ugruw | dalip | anngeeg | laal | neel’ | medlip | meeruuk | meereeb | ragaag | ||||||||||

| English | one | two | three | four | person | house | dog | road | day | new | we | what | fire |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proto-Austronesian | *əsa, *isa | *duSa | *təlu | *əpat | *Cau | *balay, *Rumaq | *asu | *zalan | *qaləjaw, *waRi | *baqəRu | *kita, *kami | *anu, *apa | *Sapuy |

| Tetum | ida | rua | tolu | haat | ema | uma | asu | dalan | loron | foun | ita | saida | ahi |

| Amis | cecay | tosa | tolo | sepat | tamdaw | luma | wacu | lalan | cidal | faroh | kita | uman | namal |

| Puyuma | sa | dua | telu | pat | taw | rumah | soan | dalan | wari | vekar | mi | amanai | apue, asi |

| Tagalog | isa | dalawa | tatlo | apat | tao | bahay | aso | daan | araw | bago | tayo / kami | ano | apoy |

| Bikol | sarô | duwá | tuló | apát | táwo | haróng | áyam | dalan | aldáw | bàgo | kitá/kami | anó | kaláyo |

| Rinconada Bikol | əsad | darwā | tolō | əpat | tawō | baləy | ayam | raran | aldəw | bāgo | kitā | onō | kalayō |

| Waray | usa | duha | tulo | upat | tawo | balay | ayam, ido |

dalan | adlaw | bag-o | kita | anu | kalayo |

| Cebuano | usa, isa |

duha | tulo | upat | tawo | balay | iro | dalan | adlaw | bag-o | kita | unsa | kalayo |

| Hiligaynon | isa | duha | tatlo | apat | tawo | balay | ido | dalan | adlaw | bag-o | kita | ano | kalayo |

| Aklanon | isaea, sambilog |

daywa | tatlo | ap-at | tawo | baeay | ayam | daean | adlaw | bag-o | kita | ano | kaeayo |

| Kinaray-a | (i)sara | darwa | tatlo | apat | tawo | balay | ayam | dalan | adlaw | bag-o | kita | ano | kalayo |

| Tausug | hambuuk | duwa | tu | upat | tau | bay | iru' | dan | adlaw | ba-gu | kitaniyu | unu | kayu |

| Maranao | isa | dowa | təlo | pat | taw | walay | aso | lalan | gawi’i | bago | səkita/səkami | antona’a | apoy |

| Kapampangan | métung | adwá | atlú | ápat | táu | balé | ásu | dálan | aldó | báyu | íkatamu | nánu | apî |

| Pangasinan | sakey | dua, duara |

talo, talora |

apat, apatira |

too | abong | aso | dalan | ageo | balo | sikatayo | anto | pool |

| Ilokano | maysa | dua | tallo | uppat | lima | innem | pito | walo | siam | sangapulo | |||

| Ivatan | asa | dadowa | tatdo | apat | tao | vahay | chito | rarahan | araw | va-yo | yaten | ango | apoy |

| Ibanag | tadday | dua | tallu | appa' | tolay | balay | kitu | dalan | aggaw | bagu | sittam | anni | afi |

| Yogad | tata | addu | tallu | appat | tolay | binalay | atu | daddaman | agaw | bagu | sikitam | gani | afuy |

| Gaddang | antet | addwa | tallo | appat | tolay | balay | atu | dallan | aw | bawu | ikkanetam | sanenay | afuy |

| Tboli | sotu | lewu | tlu | fat | tau | gunu | ohu | lan | kdaw | lomi | tekuy | tedu | ofih |

| Lun Bawang/ Lundayeh | eceh | dueh | teluh | epat | lemulun/lun | ruma' | uko' | dalan | eco | beruh | teu | enun | apui |

| Indonesian/Malay | sa/se, satu, suatu |

dua | tiga | empat | orang | rumah, balai |

anjing | jalan | hari | baru | kita, kami | apa, anu |

api |

| Old Javanese | esa, eka |

rwa, dwi |

tĕlu, tri |

pat, catur[63] |

wwang | umah | asu | dalan | dina | hañar, añar[64] | kami[65] | apa, aparan |

apuy, agni |

| Javanese | siji, setunggal |

loro, kalih |

tĕlu, tiga[66] |

papat, sekawan |

uwong, tiyang, priyantun[66] |

omah, griya, dalem[66] |

asu, sĕgawon |

dalan, gili[66] |

dina, dinten[66] |

anyar, énggal[66] |

awaké dhéwé, kula panjenengan[66] |

apa, punapa[66] |

gĕni, latu, brama[66] |

| Sundanese | hiji,

saésé |

dua, salayan | tilu, tolu | opat | urang,

jalma, jalmi |

imah,

rorompok, bumi |

anying | jalan | poé | anyar, énggal |

arurang | naon,

nahaon |

seuneu |

| Acehnese | sa | duwa | lhèë | peuët | ureuëng | rumoh, balè, seuëng |

asèë | röt | uroë | barô | (geu)tanyoë | peuë | apui |

| Minangkabau | ciek | duo | tigo | ampek | urang | rumah | anjiang | labuah, jalan |

hari | baru | awak | apo | api |

| Rejang | do | duai | tlau | pat | tun | umêak | kuyuk | dalên | bilai | blau | itê | jano, gen, inê |

opoi |

| Lampungese | sai | khua | telu | pak | jelema | lamban | kaci | ranlaya | khani | baru | kham | api | apui |

| Komering | osai | rua | tolu | pak | jolma | lombahan | asu | ranggaya | harani | anyar ompai |

ram sikam kita |

apiya | apuy |

| Buginese | se'di | dua | tellu | eppa' | tau | bola | asu | laleng | esso | baru | idi' | aga | api |

| Temuan | satuk | duak | tigak | empat | uwang, eang |

gumah, umah |

anying, koyok |

jalan | aik, haik |

bahauk | kitak | apak | apik |

| Toba Batak | sada | dua | tolu | opat | halak | jabu | biang, asu | dalan | ari | baru | hita | aha | api |

| Kelantan-Pattani | so | duwo | tigo | pak | oghe | ghumoh, dumoh |

anjing | jale | aghi | baghu | kito | gapo | api |

| Biak | oser | suru | kyor | fyak | snon | rum | naf, rofan |

nyan | ras | babo | nu, nggo |

sa, masa |

for |

| Chamorro | håcha, maisa |

hugua | tulu | fatfat | taotao/tautau | guma' | ga'lågu[67] | chålan | ha'åni | nuebu[68] | hita | håfa | guåfi |

| Motu | ta, tamona |

rua | toi | hani | tau | ruma | sisia | dala | dina | matamata | ita, ai |

dahaka | lahi |

| Māori | tahi | rua | toru | whā | tangata | whare | kurī | ara | rā | hou | tāua, tātou/tātau māua, mātou/mātau |

aha | ahi |

| Gilbertese | teuana | uoua | tenua | aua | aomata | uma, bata, auti (from house) |

kamea, kiri |

kawai | bong | bou | ti | tera, -ra (suffix) |

ai |

| Tuvaluan | tasi | lua | tolu | fá | toko | fale | kuli | ala, tuu |

aso | fou | tāua | a | afi |

| Hawaiian | kahi | lua | kolu | hā | kanaka | hale | 'īlio | ala | ao | hou | kākou | aha | ahi |

| Banjarese | asa | duwa | talu | ampat | urang | rūmah | hadupan | heko | hǎri | hanyar | kami | apa | api |

| Malagasy | isa | roa | telo | efatra | olona | trano | alika | lalana | andro | vaovao | isika | inona | afo |

| Dusun | iso | duo | tolu | apat | tulun | walai, lamin |

tasu | ralan | tadau | wagu | tokou | onu/nu | tapui |

| Kadazan | iso | duvo | tohu | apat | tuhun | hamin | tasu | lahan | tadau | vagu | tokou | onu, nunu |

tapui |

| Rungus | iso | duvo | tolu, tolzu |

apat | tulun, tulzun |

valai, valzai |

tasu | dalan | tadau | vagu | tokou | nunu | tapui, apui |

| Sungai/Tambanuo | ido | duo | tolu | opat | lobuw | waloi | asu | ralan | runat | wagu | toko | onu | apui |

| Iban | satu, sa, siti, sigi |

dua | tiga | empat | orang, urang |

rumah | ukui, uduk |

jalai | hari | baru | kitai | nama | api |

| Sarawak Malay | satu, sigek |

dua | tiga | empat | orang | rumah | asuk | jalan | ari | baru | kita | apa | api |

| Terengganuan | se | duwe | tige | pak | oghang | ghumoh, dumoh |

anjing | jalang | aghi | baghu | kite | mende, ape, gape, nape |

api |

| Kanayatn | sa | dua | talu | ampat | urakng | rumah | asu' | jalatn | ari | baru | kami', diri' |

ahe | api |

| Yapese | t’aareeb | l’ugruw | dalip | anngeeg | beaq | noqun | kuus | kanaawooq | raan | beqeech | gamow | maang | nifiiy |

See also

- Languages of Taiwan

- Austronesian Formal Linguistics Association

- List of Austronesian languages

- List of Austronesian regions

Notes

- ^ Setaria italica and Panicum miliaceum.

References

- ^ Blust, Robert Andrew. "Austronesian Languages". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ^ "Statistical Summaries; Ethnologue".

- ^ "Austronesian; Ethnologue".

- ^ Sneddon, James Neil (2004). The Indonesian Language: Its History and Role in Modern Society. UNSW Press. p. 14.)

- ^ Gonzalez, Andrew B. (1980). Language and Nationalism: The Philippine Experience Thus Far. Manila: Ateneo de Manila University Press. p. 76. ISBN 9711130009.

- ^ Robert Blust (2016). History of the Austronesian Languages. University of Hawaii at Manoa.

- ^ Pereltsvaig (2018), p. 143.

- ^ a b Dempwolff, Otto. Vergleichende Lautlehre des austronesischen Wortschatzes [Comparative phonology of the Austronesian vocabularies] (3 vols). Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für Eingeborenen-Sprachen (Supplements to the Journal of Native Languages) 15; 17; 19 (in German). Berlin: Dietrich Reimer.

- ^ John Simpson; Edmund Weiner, eds. (1989). Official Oxford English Dictionary (OED2) (Dictionary). Oxford University Press.

- ^ Blust (2013), p. 169.

- ^ Blust (2013), p. 212.

- ^ Blust (2013), pp. 215–218.

- ^ Blust (2013), pp. 220–222.

- ^ Crowley (2009), p. 100.

- ^ Blust (2013), pp. 188–189, 200, 206.

- ^ Blust (2013), p. 355.

- ^ Blust (2013), pp. 370–399.

- ^ Blust (2013), pp. 406–431.

- ^ Ross (2002), p. 453.

- ^ Adelaar, K. Alexander; Himmelmann, Nikolaus (2005). The Austronesian Languages of Asia and Madagascar. Routledge. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0415681537.

- ^ Croft, William (2012). Verbs: Aspect and Causal Structure. Oxford University Press. p. 261. ISBN 978-0199248599.

- ^ a b Greenhill, Blust & Gray 2003–2019.

- ^ Haudricourt (1965), p. 315.

- ^ Dyen (1965).

- ^ Grace (1966).

- ^ Dahl (1973).

- ^ Blust (1977).

- ^ Li (2004).

- ^ Taylor, G. (1888). "A ramble through southern Formosa". The China Review. 16: 137–161.

The Tipuns... are certainly descended from emigrants, and I have not the least doubt but that the Amias are of similar origin; only of later date, and most probably from the Mejaco Simas [that is, Miyako-jima], a group of islands lying 110 miles to the North-east.... By all accounts the old Pilam savages, who merged into the Tipuns, were the first settlers on the plain; then came the Tipuns, and a long time afterwards the Amias. The Tipuns, for some time, acknowledged the Pilam Chief as supreme, but soon absorbed both the chieftainship and the people, in fact the only trace left of them now, is a few words peculiar to the Pilam village, one of which, makan (to eat), is pure Malay. The Amias submitted themselves to the jurisdiction of the Tipuns.

- ^ Starosta, S (1995). "A grammatical subgrouping of Formosan languages". In P. Li; Cheng-hwa Tsang; Ying-kuei Huang; Dah-an Ho & Chiu-yu Tseng (eds.). Austronesian Studies Relating to Taiwan. Taipei: Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica. pp. 683–726.

- ^ Li (2008), p. 216: "The position of Rukai is the most controversial: Tsuchida... treats it as more closely related to Tsouic languages, based on lexicostatistic evidence, while Ho... believes it to be one of the Paiwanic languages, i.e. part of my Southern group, as based on a comparison of fourteen grammatical features. In fact, Japanese anthropologists did not distinguish between Rukai, Paiwan and Puyuma in the early stage of their studies"

- ^ Laurent Sagart (2004) The Higher Phylogeny of Austronesian and the Position of Tai-Kadai

- ^ Laurent Sagart (2021) A more detailed early Austronesian phylogeny. Plenary talk at the 15th International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics.

- ^ The tree can be found at the following link. Click on the nodes to see the proposed shared innovations for each.

Laurent Sagart (July 2021). "Shared innovations in early Austronesian phylogeny" (PDF). - ^ Blust (2013), p. 742.

- ^ Greenhill, Blust & Gray (2008).

- ^ Sagart (2002).

- ^ Diamond (2000).

- ^ Blust (1999).

- ^ Thurgood (1999), p. 225.

- ^ Solnit, David B. (March 1992). "Japanese/Austro-Tai By Paul K. Benedict (review)". Language. 687 (1). Linguistic Society of America: 188–196. doi:10.1353/lan.1992.0061. S2CID 141811621.

- ^ a b c d Sagart et al. 2017, p. 188.

- ^ van Driem, George (2005). "Sino-Austronesian vs. Sino-Caucasian, Sino-Bodic vs. Sino-Tibetan, and Tibeto-Burman as default theory" (PDF). In Yogendra Prasada Yadava; Govinda Bhattarai; Ram Raj Lohani; Balaram Prasain; Krishna Parajuli (eds.). Contemporary Issues in Nepalese Linguistics. Kathmandu: Linguistic Society of Nepal. pp. 285–338 [304]. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ^ Sagart et al. 2017, p. 189.

- ^ Ko 2014, pp. 426–436.

- ^ Wei et al. 2017, pp. 1–12.

- ^ Winter (2010).

- ^ Blust (2013), pp. 710–713, 745–747.

- ^ Robbeets, Martine (2017). "Austronesian influence and Transeurasian ancestry in Japanese: A case of farming/language dispersal". Language Dynamics and Change. 7 (2): 210–251. doi:10.1163/22105832-00702005. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-002E-8635-7.

- ^ Kumar, Ann (2009). Globalizing the Prehistory of Japan: Language, Genes and Civilization. Oxford: Routledge.

- ^ a b c d "Javanese influence on Japanese". Languages Of The World. 2011-05-09. Retrieved 2023-06-13.

- ^ Starosta, Stanley (2005). "Proto-East Asian and the origin and dispersal of languages of east and southeast Asia and the Pacific". In Sagart, Laurent; Blench, Roger; Sanchez-Mazas, Alicia (eds.). The Peopling of East Asia: Putting Together Archaeology, Linguistics and Genetics. London: Routledge Curzon. pp. 182–197. ISBN 978-0-415-32242-3.

- ^ van Driem, George. 2018. "The East Asian linguistic phylum: A reconstruction based on language and genes Archived 2021-01-10 at the Wayback Machine", Journal of the Asiatic Society, LX (4): 1–38.

- ^ Blevins (2007).

- ^ Blust (2014).

- ^ Zoetmulder, P.J., Kamus Jawa Kuno-Indonesia. Vol. I-II. Terjemahan Darusuprapto-Sumarti Suprayitno. Jakarta: PT. Gramedia Pustaka Utama, 1995.

- ^ "Javanese alphabet (Carakan)". Omniglot.

- ^ from the Arabic صِفْر ṣifr

- ^ Predominantly in Indonesia, comes from the Latin nullus

- ^ lapan is a known contraction of delapan; predominant in Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei.

- ^ Cook, Richard (1992). Peace Corps Marshall Islands: Marshallese Language Training Manual (PDF), pg. 22. Accessed August 27, 2007.

- ^ Percy Chatterton, (1975). Say It In Motu: An instant introduction to the common language of Papua. Pacific Publications. ISBN 978-0-85807-025-7

- ^ s.v. kawan, Old Javanese-English Dictionary, P.J. Zoetmulder and Stuart Robson, 1982

- ^ s.v. hañar, Old Javanese-English Dictionary, P.J. Zoetmulder and Stuart Robson, 1982

- ^ s.v. kami, this could mean both first person singular and plural, Old Javanese-English Dictionary, P.J. Zoetmulder and Stuart Robson, 1982

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Javanese English Dictionary, Stuart Robson and Singgih Wibisono, 2002

- ^ From Spanish "galgo"

- ^ From Spanish "nuevo"

Bibliography

- Bellwood, Peter (July 1991). "The Austronesian Dispersal and the Origin of Languages". Scientific American. 265 (1): 88–93. Bibcode:1991SciAm.265a..88B. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0791-88.

- Bellwood, Peter (1997). Prehistory of the Indo-Malaysian archipelago. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

- Bellwood, Peter (1998). "Taiwan and the Prehistory of the Austronesians-speaking Peoples". Review of Archaeology. 18: 39–48.

- Bellwood, Peter; Fox, James; Tryon, Darrell (1995). The Austronesians: Historical and comparative perspectives. Department of Anthropology, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-7315-2132-6.

- Bellwood, Peter; Sanchez-Mazas, Alicia (June 2005). "Human Migrations in Continental East Asia and Taiwan: Genetic, Linguistic, and Archaeological Evidence". Current Anthropology. 46 (3): 480–484. doi:10.1086/430018. S2CID 145495386.

- Blench, Roger (June 10–13, 2004). Stratification in the peopling of China: how far does the linguistic evidence match genetics and archaeology? (PDF). Human migrations in continental East Asia and Taiwan: genetic, linguistic and archaeological evidence. Geneva.

- Blevins, Juliette (2007). "A Long Lost Sister of Proto-Austronesian? Proto-Ongan, Mother of Jarawa and Onge of the Andaman Islands" (PDF). Oceanic Linguistics. 46 (1): 154–198. doi:10.1353/ol.2007.0015. S2CID 143141296. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-01-11.

- Blust, Robert (1977). "The Proto-Austronesian pronouns and Austronesian subgrouping: a preliminary report". Working Papers in Linguistics. 9 (2). Honolulu: Department of Linguistics, University of Hawaii: 1–15.

- Blust, Robert (1985). "The Austronesian Homeland: A Linguistic Perspective". Asian Perspectives. 26: 46–67.

- Blust, Robert (1999). "Subgrouping, circularity and extinction: some issues in Austronesian comparative linguistics". In Zeitoun, E.; Li, P.J.K (eds.). Selected papers from the Eighth International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics. Taipei: Academia Sinica. pp. 31–94.

- Blust, Robert (2013). The Austronesian Languages (revised ed.). Australian National University. hdl:1885/10191. ISBN 978-1-922185-07-5.

- Blust, Robert (2014). "Some Recent Proposals Concerning the Classification of the Austronesian Languages". Oceanic Linguistics. 53 (2): 300–391. doi:10.1353/ol.2014.0025. S2CID 144931249.

- Comrie, Bernard (2001). "Languages of the world". In Aronoff, Mark; Rees-Miller, Janie (eds.). The Handbook of Linguistics. Languages of the world. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 19–42. ISBN 1-4051-0252-7.

- Crowley, Terry (2009). "Austronesian languages". In Brown, Keith; Ogilvie, Sarah (eds.). Concise Encyclopaedia of Languages of the World. Oxford: Elsevier. pp. 96–105.

- Dahl, Otto Christian (1973). Proto-Austronesian. Lund: Skandinavian Institute of Asian Studies.

- Diamond, Jared M (2000). "Taiwan's gift to the world". Nature. 403 (6771): 709–10. Bibcode:2000Natur.403..709D. doi:10.1038/35001685. PMID 10693781.

- Dyen, Isidore (1965). "A Lexicostatistical classification of the Austronesian languages". International Journal of American Linguistics (Memoir 19).

- Fox, James J. (19–20 August 2004). Current Developments in Comparative Austronesian Studies (PDF). Symposium Austronesia Pascasarjana Linguististik dan Kajian Budaya. Universitas Udayana, Bali. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2006. Retrieved 10 August 2006.

- Fuller, Peter (2002). "Reading the Full Picture". Asia Pacific Research. Canberra, Australia: Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved July 28, 2005.

- Grace, George W. (1966). "Austronesian Lexicostatistical Classification:a review article (Review of Dyen 1965)". Oceanic Linguistics. 5 (1): 13–58. doi:10.2307/3622788. JSTOR 3622788.

- Greenhill, S.J.; Blust, R.; Gray, R.D. (2008). "The Austronesian Basic Vocabulary Database: From Bioinformatics to Lexomics". Evolutionary Bioinformatics. 4. SAGE Publications: 271–283. doi:10.4137/EBO.S893. PMC 2614200. PMID 19204825.

- Greenhill, S.J.; Blust, R.; Gray, R.D. (2003–2019). "Austronesian Basic Vocabulary Database". Archived from the original on 2018-12-19. Retrieved 2018-12-19.

- Haudricourt, André G. (1965). "Problems of Austronesian comparative philology". Lingua. 14: 315–329. doi:10.1016/0024-3841(65)90048-3.

- Ko, Albert Min-Shan; et al. (2014). "Early Austronesians: Into and Out Of Taiwan". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 94 (3): 426–36. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.02.003. PMC 3951936. PMID 24607387.

- Li, Paul Jen-kuei (2004). "Origins of the East Formosans:Basay, Kavalan, Amis, and Siraya" (PDF). Language and Linguistics. 5 (2): 363–376. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-04-18. Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- Li, Paul Jen-kuei (2006). The Internal Relationships of Formosan Languages. Tenth International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics (ICAL). Puerto Princesa City, Palawan, Philippines.

- Li, Paul Jen-kuei (2008). "Time perspective of Formosan Aborigines". In Sanchez-Mazas, Alicia; Blench, Roger; Ross, Malcolm D.; Peiros, Ilia; Lin, Marie (eds.). Past human migrations in East Asia: matching archaeology, linguistics and genetics. London: Routledge. pp. 211–218.

- McColl, Hugh; Racimo, Fernando; Vinner, Lasse; Demeter, Fabrice; Gakuhari, Takashi; et al. (2018-07-05). "The prehistoric peopling of Southeast Asia". Science. 361 (6397). American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS): 88–92. Bibcode:2018Sci...361...88M. bioRxiv 10.1101/278374. doi:10.1126/science.aat3628. hdl:10072/383365. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 29976827. S2CID 206667111.

- Lynch, John; Ross, Malcolm; Crowley, Terry (2002). The Oceanic languages. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon Press. ISBN 0-415-68155-3.

- Melton, T.; Clifford, S.; Martinson, J.; Batzer, M.; Stoneking, M. (1998). "Genetic evidence for the proto-Austronesian homeland in Asia: mtDNA and nuclear DNA variation in Taiwanese aboriginal tribes". American Journal of Human Genetics. 63 (6): 1807–23. doi:10.1086/302131. PMC 1377653. PMID 9837834.

- Ostapirat, Weera (2005). "Kra–Dai and Austronesian: Notes on phonological correspondences and vocabulary distribution". In Laurent, Sagart; Blench, Roger; Sanchez-Mazas, Alicia (eds.). The Peopling of East Asia: Putting Together Archaeology, Linguistics and Genetics. London: Routledge Curzon. pp. 107–131.

- Peiros, Ilia (2004). Austronesian: What linguists know and what they believe they know. The workshop on Human migrations in continental East Asia and Taiwan. Geneva.

- Pereltsvaig, Asya (2018). Languages of the World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-62196-7.

- Ross, Malcolm (2009). "Proto Austronesian verbal morphology: a reappraisal". In Adelaar, K. Alexander; Pawley, Andrew (eds.). Austronesian Historical Linguistics and Culture History: A Festschrift for Robert Blust. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. pp. 295–326.

- Ross, Malcolm; Pawley, Andrew (1993). "Austronesian historical linguistics and culture history". Annual Review of Anthropology. 22: 425–459. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.22.100193.002233. OCLC 1783647.

- Ross, John (2002). "Final words: research themes in the history and typology of western Austronesian languages". In Wouk, Fay; Malcolm, Ross (eds.). The history and typology of Western Austronesian voice systems. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. pp. 451–474.

- Sagart, Laurent; Hsu, Tze-Fu; Tsai, Yuan-Ching; Hsing, Yue-Ie C. (2017). "Austronesian and Chinese words for the millets". Language Dynamics and Change. 7 (2): 187–209. doi:10.1163/22105832-00702002. S2CID 165587524.

- Sagart, Laurent (8–11 January 2002). Sino-Tibeto-Austronesian: An updated and improved argument (PDF). Ninth International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics (ICAL9). Canberra, Australia.

- Sagart, Laurent (2004). "The higher phylogeny of Austronesian and the position of Tai–Kadai". Oceanic Linguistics. 43 (2): 411–440. doi:10.1353/ol.2005.0012. S2CID 49547647.

- Sagart, Laurent (2005). "Sino-Tibeto-Austronesian: An updated and improved argument". In Blench, Roger; Sanchez-Mazas, Alicia (eds.). The Peopling of East Asia: Putting Together Archaeology, Linguistics and Genetics. London: Routledge Curzon. pp. 161–176. ISBN 978-0-415-32242-3.

- Sapir, Edward (1968) [1949]. "Time perspective in aboriginal American culture: a study in method". In Mandelbaum, D.G. (ed.). Selected writings of Edward Sapir in language, culture and personality. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 389–467. ISBN 0-520-01115-5.

- Taylor, G. (1888). "A ramble through southern Formosa". The China Review. 16: 137–161. Archived from the original on 2021-04-11. Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- Thurgood, Graham (1999). From Ancient Cham to Modern Dialects. Two Thousand Years of Language Contact and Change. Oceanic Linguistics Special Publications No. 28. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2131-9.

- Trejaut, J. A.; Kivisild, T.; Loo, J. H.; Lee, C. L.; He, C. L. (2005). "Traces of archaic mitochondrial lineages persist in Austronesian-speaking Formosan populations". PLOS Biol. 3 (8): e247. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030247. PMC 1166350. PMID 15984912.

- Wei, Lan-Hai; Yan, Shi; Teo, Yik-Ying; Huang, Yun-Zhi; et al. (2017). "Phylogeography of Y-chromosome haplogroup O3a2b2-N6 reveals patrilineal traces of Austronesian populations on the eastern coastal regions of Asia". PLOS ONE. 12 (4): 1–12. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1275080W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0175080. PMC 5381892. PMID 28380021.

- Winter, Bodo (2010). "A Note on the Higher Phylogeny of Austronesian". Oceanic Linguistics. 49 (1): 282–287. doi:10.1353/ol.0.0067. JSTOR 40783595. S2CID 143458895.

- Wouk, Fay; Ross, Malcolm, eds. (2002). The history and typology of western Austronesian voice systems. Pacific Linguistics. Canberra: Australian National University.

Further reading

- Bengtson, John D., The "Greater Austric" Hypothesis, Association for the Study of Language in Prehistory.

- Blundell, David. "Austronesian Dispersal". Newsletter of Chinese Ethnology. 35: 1–26.

- Blust, R. A. (1983). Lexical reconstruction and semantic reconstruction: the case of the Austronesian "house" words. Hawaii: R. Blust.

- Cohen, E. M. K. (1999). Fundaments of Austronesian roots and etymology. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. ISBN 0-85883-436-7

- Marion, P., Liste Swadesh élargie de onze langues austronésiennes, éd. Carré de sucre, 2009

- Pawley, A., & Ross, M. (1994). Austronesian terminologies: continuity and change. Canberra, Australia: Dept. of Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University. ISBN 0-85883-424-3

- Sagart, Laurent, Roger Blench, and Alicia Sanchez-Nazas (Eds.) (2004). The peopling of East Asia: Putting Together Archaeology, Linguistics and Genetics. London: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-415-32242-1.

- Terrell, John Edward (December 2004). "Introduction: 'Austronesia' and the great Austronesian migration". World Archaeology. 36 (4): 586–590. doi:10.1080/0043824042000303764. S2CID 162244203.

- Tryon, D. T., & Tsuchida, S. (1995). Comparative Austronesian dictionary: an introduction to Austronesian studies. Trends in linguistics, 10. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3110127296

- Wittmann, Henri (1972). "Le caractère génétiquement composite des changements phonétiques du malgache." Proceedings of the International Congress of Phonetic Sciences 7.807–810. La Haye: Mouton.

- Wolff, John U., "Comparative Austronesian Dictionary. An Introduction to Austronesian Studies", Language, vol. 73, no. 1, pp. 145–156, Mar 1997, ISSN 0097-8507

External links

- Blust's Austronesian Comparative Dictionary

- Swadesh lists of Austronesian basic vocabulary words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

- "Homepage of linguist Dr. Lawrence Reid". Retrieved July 28, 2005.

- Summer Institute of Linguistics site showing languages (Austronesian and Papuan) of Papua New Guinea.

- "Austronesian Language Resources". Archived from the original on November 22, 2004.

- Spreadsheet of 1600+ Austronesian and Papuan number names and systems – ongoing study to determine their relationships and distribution[permanent dead link]

- Languages of the World: The Austronesian (Malayo-Polynesian) Language Family

- Introduction to Austronesian Languages and Culture (video) (Malayo-Polynesian) Language Family on YouTube

- 南島語族分布圖 Archived 2014-06-30 at the Wayback Machine