Arwa al-Sulayhi: Difference between revisions

m Copying from Category:11th-century women regents to Category:11th-century regents using Cat-a-lot |

→Name: An Arab name existing since before Islam. |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

== Name == |

== Name == |

||

The name Arwa ({{lang-ar|أَرْوَى|Arwā'}}) literally means "female [[ibex]]".<ref name="El-Azhari 2021"/> It is also a traditional |

The name Arwa ({{lang-ar|أَرْوَى|Arwā'}}) literally means "female [[ibex]]".<ref name="El-Azhari 2021"/> It is also a traditional Arab name for girls connoting gracefulness, beauty, softness, and liveliness.<ref name="Haeri 2020"/> There is some controversy over whether this was actually her real name - S.M. Stern<ref name="Hamdani 1974">{{cite journal |last1=Hamdani |first1=Abbas |title=The dāʿī Ḥātim ibn Ibrāhīm al-Ḥāmidī (d. 596 H./ 1199 A.D.) and His Book "Tuḥfat al-qulūb" |journal=Oriens |date=1974 |volume=23/24 |pages=258–300 |doi=10.2307/1580105 |jstor=1580105 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/1580105 |access-date=30 April 2022}}</ref> and Sultan Naji,<ref name="Naji">{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JMBJLwjTj8cC&q=%22Sayyidah+bint+Ahmed%22|title=Bibliyūjrāfiyā Mukhtārah Wa-tafsīrīyah ʻan Al-Yaman|last=Nājī|first=Sulṭān|date=1973|publisher=Kuwait University, Libraries Department|page=184}}</ref> for example, argue that Arwa's real name was Sayyidah, not Arwa.<ref name="Hamdani 1974"/><ref name="Naji"/> Stern suggested a possible confusion with a different Sulayhid princess named Arwa,<ref name="Hamdani 1974"/> and Naji wrote that she is "wrongly called Arwa".<ref name="Naji"/> However, Abbas Hamdani says that early Isma'ili sources do in fact call her Arwa, such as [[Idris Imad al-Din]] and one version of [[Umara ibn Abi al-Hasan al-Yamani|'Umara al-Yamani]]'s ''Tarikh''.<ref name="Hamdani 1974"/> The name "as-Sayyidah al-Hurrah", or "the noble lady", is used in these texts as an honorific title "qualifying the name Arwa".<ref name="Hamdani 1974"/> Hamdani says Arwa was probably known interchangeably by both names during her own lifetime.<ref name="Hamdani 1974"/> Samer Traboulsi argues that the names "Sayyidah" and "Sayyidah Hurrah" are "titles used out of respect" and that Arwa was her actual name.<ref name="Traboulsi 2003">{{cite journal |last1=Traboulsi |first1=Samer |title=The Queen was Actually a Man: Arwā Bint Aḥmad and the Politics of Religion |journal=Arabica |date=2003 |volume=50 |issue=1 |pages=96–108 |doi=10.1163/157005803321112164 |jstor=4057749 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/4057749 |access-date=30 April 2022}}</ref> |

||

==Sources== |

==Sources== |

||

Revision as of 11:23, 17 May 2024

Malikah (Template:Lang-ar) Arwā bint Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn Jaʿfar ibn Mūsā Aṣ-Ṣulayḥī | |

|---|---|

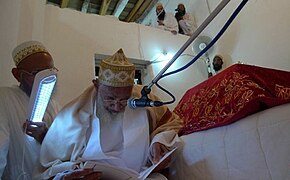

Mausoleum of Queen Arwa inside Queen Arwa Mosque, Jibla | |

| Born | 440 Hijri (1048 CE) |

| Died | 1138 (aged 89–90) |

| Resting place | Queen Arwa Mosque, Jibla |

| Other names | As-Sayyidah Al-Ḥurrah ([ٱلسَّيِّدَة ٱلْحُرَّة] Error: {{Lang}}: invalid parameter: |lit= (help)) Al-Malikah Al-Ḥurrah (Template:Lang-ar or Al-Ḥurratul-Malikah (Template:Lang-ar) Malikat Sabaʾ Aṣ-Ṣaghīrah (مَلِكَة سَبَأ ٱلصَّغِيْرَة, "Little Queen of Sheba") |

| Known for | Being a long-reigning Queen of Yemen and Islam |

| Predecessor | Asma bint Shihab |

| Successor | (Sulayhid Dynasty abolished) |

| Spouses | |

| Children | Abd al-Imam Muhammad Abd al-Mustansir Ali Fatimah Umm Hamdan |

| Father | Ahmad ibn Muhammad |

| Part of a series on Islam Isma'ilism |

|---|

|

|

|

Arwa al-Sulayhi, full name Arwā bint Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn Jaʿfar ibn Mūsā aṣ-Ṣulayḥī (Template:Lang-ar, c. 1048–1138, died 22nd Shaban, 532 AH or May 5, 1138 was a long-reigning ruler of Yemen, firstly as the co-ruler of her first two husbands and then as sole ruler, from 1067 until her death in 1138.[1] She was the last of the rulers of the Sulayhid Dynasty and was also the first woman to be accorded the prestigious title of Hujjah in the Isma'ili branch of Shia Islam, signifying her as the closest living image of God's will in her lifetime, in the Ismaili doctrine. She is popularly referred to as As-Sayyidah Al-Ḥurrah (Template:Lang-ar), Al-Malikah Al-Ḥurrah (Template:Lang-ar or Al-Ḥurratul-Malikah (Template:Lang-ar), and Malikat Sabaʾ Aṣ-Ṣaghīrah (Template:Lang-ar).

As female sovereign, Arwa has an almost unique position in history: though there were more female monarchs in the international Muslim world, Arwa and Asma bint Shihab were the only female monarchs in the Muslim Arab world to have had the khutbah, the ultimate recognition of Muslim monarchial status, proclaimed in their name in the mosques.[2] She founded several mosques, the most prominent of which is Queen Arwa Mosque.

Arwa was the first queen regnant in the Muslim world.[3] Through her title of hujjah, she is the only Muslim woman to ever wield both political and religious authority in her own right.[1]

Her political career can basically be divided into four parts.[3] The first spans the period from her marriage to al-Mukarram Ahmad in 1065 until the death of her mother-in-law Asma in 1074.[3] During this period, there is no evidence that she held any political power.[3] The second begins after Asma's death, and Ahmad began to delegate all power to Arwa at that point until his 1086 death.[3] Third, after his death, Arwa wielded power as queen mother to her son Abd al-Mustansir, and she was also ordered by al-Mustansir to marry Saba' al-Sulayhi (although never consummated) for legitimacy and then was nominally consort even if she held the real power.[3] Finally, after Saba's death in 1097 or 1098, Arwa reigned as sole queen in her own right, with no male nominally in charge.[3]

Name

The name Arwa (Template:Lang-ar) literally means "female ibex".[3] It is also a traditional Arab name for girls connoting gracefulness, beauty, softness, and liveliness.[1] There is some controversy over whether this was actually her real name - S.M. Stern[4] and Sultan Naji,[5] for example, argue that Arwa's real name was Sayyidah, not Arwa.[4][5] Stern suggested a possible confusion with a different Sulayhid princess named Arwa,[4] and Naji wrote that she is "wrongly called Arwa".[5] However, Abbas Hamdani says that early Isma'ili sources do in fact call her Arwa, such as Idris Imad al-Din and one version of 'Umara al-Yamani's Tarikh.[4] The name "as-Sayyidah al-Hurrah", or "the noble lady", is used in these texts as an honorific title "qualifying the name Arwa".[4] Hamdani says Arwa was probably known interchangeably by both names during her own lifetime.[4] Samer Traboulsi argues that the names "Sayyidah" and "Sayyidah Hurrah" are "titles used out of respect" and that Arwa was her actual name.[6]

Sources

There are three main sources for Arwa's life.[3] The first is the Ta'rikh al-Yaman, or "History of Yemen", by the 12th-century Umara al-Yamani.[3] Umara was a Fatimid sympathizer, despite being a Sunni, who settled in Egypt in 1164.[3] His book covered the Sulayhid dynasty and influenced later chroniclers like Taj al-Din al-Yamani, Ali al-Khazraji, and Yahya ibn al-Husayn.[3]

The second is the 'Uyun al-Akhbar wa Funun al-Athar, by Idris Imad al-Din, the 19th Tayyibi Isma'ili da'i mutlaq who lived during the 15th century.[3] Volume 7 of this work was dedicated to the religious doctrinal history of the Sulayhids.[3] His work is important because, as a da'i, he had insider access to sources that would have been off-limits for others.[3]

Finally, there is the sijillat between the Sulayhids and the Fatimids, which are important as a primary source.[3] The Sijillat al-Mustansiriyya, which comprises 66 sijills that were sent from the Fatimid chancery to the Sulayhids, is the main source for this; it found its way to Gujarat in India.[3]

In general, Isma'ili sources have historically been very limited because they have been off-limits to everyone except followers of the da'wah.[3] They are found in Isma'ili libraries throughout Yemen, western India, Iran, and Central Asia but only available to approved adherents.[3] They have also been made available through the Institute of Ismaili Studies in London.[3] This has contributed to some of the obscurity surrounding Arwa and her life.[3] Another contributing factor is that Egyptian (such as Ibn Muyassar, al-Maqrizi, and Ibn Taghribirdi) and Iraqi (such as Ibn al-Athir) historians generally paid little attention to Yemen during the Fatimid era.[3]

Life and reign

Arwa was born in 1047 or 1048 CE (440 AH) to Ahmad ibn al-Qasim al-Sulayhi and al-Raddah al-Sulayhi.[3] The Sulayhid ruler Ali al-Sulayhi was her paternal uncle.[1][note 1] Her father (Ahmad) died while she was young (the exact date is never stated) and her mother remarried 'Amir ibn Sulayman al-Zawahi, a member of an allied tribe who would later become one of Arwa's major political rivals.[1] After her father's death, Arwa was raised in the royal palace under Ali and Asma.[3] The royal couple supposedly realized her intelligence early on and provided her with the best education available.[1] (According to Umara, the Sulayhids in general took pride in providing good education for their women.)[7]

In 1065/6 (458 AH),[note 2] around the age of 18, Arwa was married to her paternal cousin, the wali al-ahd (crown prince) al-Mukarram Ahmad.[7][3] This marriage was arranged by Ali shortly after his older son and original heir al-A'azz died.[4][note 3] As her mahr, or bride wealth, Ali gave Arwa the net yearly revenue from the city of Aden, which amounted to 100,000 dinars.[7] This was paid by the Ma'nid emirs of Aden, but they later suspended its payment when Ali died, only to be resumed when al-Mukarram Ahmad restored Sulayhid authority there.[7][note 4]

Arwa had four children with al-Mukarram Ahmad: Fatimah (d. 1140), who married Ali b. Saba'; Umm Hamdan (d. 1122), who married her cousin Ali al-Zawahi; and two sons Muhammad and Ali who both died in childhood around 1087.[3][note 5]

As queen consort

In 1067, Ali al-Sulayhi was killed by the Najahid ruler of Zabid, Sa'id.[7] Queen Asma was taken prisoner in Zabid along with several other women.[7] Al-Mukarram Ahmad succeeded Ali as both king and da'i, bringing Arwa to the new rank of queen consort.[1] Local rulers across Yemen were rising up in defiance of Sulayhid authority, hoping to take advantage of the power vacuum after Ali's death.[6] Ahmad spent the next few years campaigning to try and reassert his authority, which he eventually succeeded at doing.[6]

According to Shahla Haeri and Taef El-Azhari, there is no evidence that Arwa was ever in a position of political or religious authority during this period.[3][1] According to Samer Traboulsi, however, al-Mukarram's absence during his continuous campaigning would have given Arwa a chance to play a political role.[6]

The role of Asma bint Shihab at this point is disputed, as is her influence on Arwa. According to Fatema Mernissi, Asma had in effect been co-ruler of Yemen alongside her husband Ali during his life, and then was the power behind the throne during al-Mukarram's nominal reign.[2] Taef El-Azhari, however, says that this assertion is not supported by contemporary sources - while they do portray Asma as a highly esteemed individual, there is only one instance of her actually setting policy: in 1063, when she got her brother As'ad appointed as deputy over the Tihama region.[3] As a result, El-Azhari says, Asma was probably not a major influence on Arwa's political career.[3] On the other hand, Delia Cortese and Simonetta Calderini suggest that Umara's account of Asma convincing her son to wage war on another tribe indicates that she did wield political influence during his reign.[7] They also point to Ibn Khaldun, who "candidly" wrote that Asma was the one who was really in charge during her son's early reign.[7] Meanwhile, Shahla Haeri says that Asma was "in charge of political affairs and governance, controlling sensitive strategic information and managing all state and financial matters" until her death, and that Arwa "might have learned from Asma simply by observing her or assisting her in her various official duties, given the close relationship between the two women and the ease with which Arwa replaced her mother-in-law after her death".[1]

1074–1084: regency for al-Mukarram Ahmad

Asma died in 1074/5 (467 CE), and Ahmad became bedridden due to paralysis soon after.[1][7][4][6][note 6] Based on Umara's account, Ahmad's paralysis (or paraplegia) may have been caused by wounds sustained in battle at Zabid against the Najahids at the start of his reign.[4] While Ahmad remained the de jure ruler of Yemen, Arwa became the de facto sovereign as he delegated all power to her.[4][1][3][7]

According to Husain Hamdani (1931), Ahmad delegated responsibility to Arwa because he "honored the counsel of his wife and had great faith in her shrewdness and intelligence".[1] The 12th-century account by Umara al-Yamani, however, attributes this decision to Ahmad having "given himself up to the pleasures of music and wine" and wanting to pass off the responsibility of governing to his wife.[7] In Umara's version, Arwa was reluctant to accept this authority, saying "a woman who is [still] desirable in bed is not suitable for running a state".[7] Cortese and Calderini say that "while this statement is presented as an expression of her personal reservations, one suspects that it was indeed constructed by the panegyrist Umara as a device to praise her modesty by showing her reluctance to be thrown into the spotlight."[7] Umara may have also been uncomfortable with this gender role reversal and needing to find a culturally acceptable rationalization for it.[1]

In practice, whether Umara's description of her reluctance is true or not, Arwa seems to have had "few, if any, qualms about her gender or the extent of her political authority".[1] Not long after becoming regent, she made two important decisions.[3] The first was moving the capital from Sanaa to Dhu Jibla, further south.[3] Ostensibly this was for medical reasons on Ahmad's behalf.[7] Most likely, however, the decision to relocate was made because the Sulayhids wanted a better capital than Sanaa, "where Sulayhid authority was being eroded".[7][note 7] Arwa marched in person at the head of an army to Dhu Jibla, where she enlarged the city and supervised personally the construction of the new Dar al-'Izz palace.[3] She would reside here for most of the year, while al-Mukarram would reside in the nearby citadel of al-Ta'kar.[3][note 8]

The second decision she made was the bold move to have the khutbah proclaimed in her name, after those of the caliph and her husband.[3] This is the first time the khutbah was ever said in a woman's name.[3]

In contrast to her mother-in-law, Queen Asma, Arwa did not appear unveiled when she attended councils as Asma had famously done.[2] The reason for this was reported because she was much younger than her mother-in-law, it would have potentially been more scandalous in her case to follow that example.[2] However, although she was veiled, she still attended state councils in person and thus mixed with men, and refused to conduct the meetings hidden by a screen.[2]

In 1075 she made a move against the Najahid leader Sa'id al-Ahwal, leading to "the mother of all battles", as Umara described it.[3] The Najahids were devastated, and Arwa had Sa'id's head displayed directly under her room's window at the palace at Dhu Jibla.[3] This was both to avenge Ali's death and to "show her strength and determination domestically, in addition to eliminating the Najahids in her western territories".[3]

Arwa's extensive correspondence with the Fatimid chancery is first attested during this period, in the form of three sijills addressed to her between 1078 and 1080.[3] The first (#44) is dated to August 1078, the second (#20) is from April 1080, and the third (#21) is undated but probably was also sent in 1080.[3] Another, sijill #51, was sent to her from the Fatimid queen mother Rasad in 1078.[3] These sijills do not call Arwa "queen", but they do give her extensive titles such as "deputy of the commander of the faithful".[3] The first and third don't even mention Ahmad, the nominal ruler, indicating that the Fatimids at this point recognized Arwa as the de facto sovereign over Yemen.[3]

Important members of Arwa's administration during the 1070s included the qadi 'Imran al-Yami and Abu al-Futuh ibn As'ad.[3] Her mother's husband 'Amir al-Zawahi and her own husband's cousin Saba' ibn Ahmad al-Sulayhi, who both went on to play an important role in the 1080s, are not mentioned in historical chronicles during the 1070s.[3] They likely were already important during this period but the chronicles simply do not mention them yet.[3]

1084–1097/8: regency for Abd al-Mustansir and marriage to Saba' ibn Ahmad

Al-Mukarram Ahmad died at al-Ta'kar in October 1084.[3][note 9] He left a will stating that his cousin Saba' should succeed him.[3] Arwa concealed the news of her husband's death and wrote to the Fatimids to request the appointment of her 10-year-old son Abd al-Mustansir Ali as the official new Sulayhid ruler.[3][note 10] The reply came in a sijill dated to July 1085 and described Arwa as "the one on whom the caliph would depend to guard the da'wah, and to loyally serve Fatimid affairs".[3]

This was an especially precarious transitional period, and some tribal leaders used the chance to challenge Arwa's authority.[1] Aden and other areas again seceded from Sulayhid rule.[3] This period witnessed the most intensive correspondence between the Fatimids and Sulayhids, with as many as 11 sijills sent concerning the succession of Abd al-Mustansir.[6]

At about this time, the Fatimid caliph issued an unprecedented decree that raised Arwa to the rank of hujjah - the highest rank in the Isma'ili hierarchy after the caliph himself.[6][1] This decree, unfortunately, only survives in a quotation from Idris Imad al-Din.[6] It said Arwa had been given this rank because she had received the "wisdom and science of the imam" by some of the da'wah's most esteemed members (probably referring to Lamak ibn Malik).[6] As a result, she was now to be considered a model religious figure whose example should be followed by the Isma'ili community.[6]

Whether Arwa was hujjah in religious matters or solely a political figurehead is debated.[1] Husain Hamdani writes that Arwa was given full authority over both spiritual and political matters, while Delia Cortese and Simonetta Calderini say that al-Mustansir's decision must have been based on solid theological ground.[1] On the other hand, Samer Traboulsi argues that her role as hujjah was essentially symbolic and she had no role in actually running the da'wah in Yemen - that was done by Lamak ibn Malik.[6] There is no evidence that women were actually ever allowed to hold any positions within the da'wah outside of her unique case.[6] Her appointment was political, rather than religious, and was motivated by the Fatimids wanting to promote stability in the region by authorizing Arwa (who was already an experienced political figure).[6] Abbas Hamdani similarly says that Arwa's "institutional authority was also more concentrated on 'the temporal side'", and Farhad Daftary says that "the term hujjah was also used in a more limited sense".[1]

Whatever the exact nature of her hujjah-ship was, Arwa now ruled Yemen as regent for her son Abd al-Mustansir, with Lamak in charge of administering the da'wah.[1] She also empowered Saba', who held the title amir al-ajall, to oversee the security of the Sulayhid state.[1][6] She also put him in charge of her sons' education.[1]

Saba' was unsuccessful in his new task as a military leader and his army was defeated in 1086 by a Najahid-Zaydi coalition.[6] Not long after this defeat, Arwa's stepfather, 'Amir ibn Sulayman al-Zawahi, rose in revolt against Saba'.[6] The sources are silent about the causes for this conflict but it was probably over control of the Sulayhid state - as a woman, Arwa was seen as unfit to rule.[6]

Arwa sent a letter to al-Mustansir explaining the precarious situation in Yemen.[6] Her letter has not survived, but the sijill al-Mustansir sent in reply has.[6] In it - the only one of his 66 sijills to be directed to the general public - he admonished the people to obey Arwa's authority, because he had only given her authority once he was sure of her wisdom and piety, and to disobey her was to disobey the imam himself.[6] Soon afterwards, the civil war ended and Saba' and 'Amir were reconciled.[6]

Around 1090, Abd al-Mustansir died suddenly.[3] According to Samer Traboulsi, Arwa's younger son Muhammad had already died a short while earlier, leaving Arwa as the sole ruler.[6] According to Taef El-Azhari, on the other hand, Muhammad inherited his brother's nominal throne.[3] In any case, Saba' started to demand his right to be king at this point[3] and proposed marriage to Arwa.[6]

According to some chronicles, Saba's proposal led to a military standoff with Arwa as she refused his proposal.[3] El-Azhari considers this "highly improbable" but describes how it reflects her power.[3] The supposed confrontation happened when Saba' quickly headed to Dhu Jibla with his army, only to be refused entry to the palace when he arrived.[6] He waited outside for a while but eventually realized that Arwa was not going to let him marry her, so he ended up returning to his own fortress in embarrassment.[6][note 11]

Whether this story is true or not, Saba's marriage proposal ended up getting official Fatimid support.[3] Al-Mustansir gave this proposal his blessing and sent an ustadh (a high court official) to inform Arwa of his orders that she marry Saba'.[6][note 12] Arwa had no choice but to obey the imam's command and agreed.[6] The marriage contract was concluded, but it's doubtful that it was ever consummated.[3]

This event indicates a shift in Fatimid attitudes towards Arwa.[6] After the deaths of her sons, they were no longer willing to back her - perhaps they thought a woman should not be in power for that long - and they planned for her to be married to a man, Saba', who would then hold actual power.[6] His marriage to Arwa would help give his rule legitimacy among the local sultans and tribal shaykhs.[6]

Al-Mustansir died in 1094 without a clear successor, leading to a conflict over the Fatimid succession between his sons al-Musta'li and Nizar.[3] The mother of al-Musta'li sent Arwa an epistle in 1096 (sijill #35), seeking support for her son's rule.[3] Al-Musta'li himself followed suit soon after.[1] Realizing the strength of al-Musta'li's political position, Arwa pragmatically chose to support him.[3] Notably, the Fatimids never sent any sijills to Saba', even though he was nominally king at this point, indicating that Arwa still held de facto power in Yemen.[3]

1097/8–1138: independent rule

Saba' died in 1098 (491 AH) and 'Amir died a year later, in 1099 (492 AH).[4] Arwa was thus freed of her two main political rivals,[6] and she was now the uncontested monarch of Yemen in her own right, without any need for marriage or sons.[3] Arwa was publicly named al-malika, or "queen" - the first time this had ever happened in the Islamic world.[3] This time, the Fatimids appear to have accepted Arwa as sovereign.[3] Chroniclers like 'Umara al-Yamani or Idris Imad al-Din never mention any later Fatimid decrees expressing that they were upset with Arwa remaining in power this way, or that they objected to her policies.[6] According to Taef El-Azhari, the reason for their acquiescence this time is because they were already preoccupied with the Nizari-Musta'li schism and, after 1097, with the First Crusade.[3]

However, with the deaths of Saba' and 'Amir - as well as Lamak, who had died at about the same time - Arwa was left without some of her most important advisors.[4] She appointed the loyal amir al-Mufaddal ibn Abi'l-Barakat al-Himyari to succeed Saba' as army commander and to guard the royal treasures at al-Ta'kar.[3][4] Al-Mufaddal was antagonistic towards Saba's family and may have been responsible for alienating the rulers of Aden and Sanaa, who now broke away from Sulayhid rule.[4] Al-Mufaddal led various campaigns throughout Yemen in order to restore Arwa's authority.[3] He was most successful in bringing the Zuray'ids of Aden into submission, who agreed to pay an annual tribute of 50,000 dinars (half of what they had paid previously).[3] Sanaa, on the other hand, broke away for good under the Hamdanids, supported by the family of Qadi 'Imran al-Yami.[4]

In 1109, the ruler of the Tihama, Fatik, died.[3] His successor, al-Mansur, was just an infant, and the region was plunged into civil war.[3] Some local commanders went to al-Mufaddal and offered to pay a quarter of the Tihama's annual revenues to Arwa as tribute in return for military support.[3] In 1110, while al-Mufaddal was away campaigning in the Tihama, there was a coup at al-Ta'kar against the deputy governor he had appointed there.[3] Led by a group of Sunni jurists and backed by the Khawlan tribe, the coup succeeded in taking control of the citadel.[3] Al-Mufaddal went to try and retake al-Ta'kar, but he died on the way.[3] When Arwa heard of this, she marched in person at the head of an army - a rare occurrence - to al-Ta'kar, where she negotiated with the coup leaders and successfully brought al-Ta'kar back under her control.[3]

After al-Mufaddal's death, Sulayhid control over Yemen weakened.[3] Aden broke away again, and at one point even al-Ta'kar was lost again for a while.[3] Arwa appointed al-Mufaddal's cousin, As'ad ibn Abi'l-Futuh, to succeed him as deputy, but he does not seem to have been very effective.[3] In 1119, Arwa, now 65 years old, wrote to the Fatimids requesting assistance.[3] The Fatimid vizier al-Afdal Shahanshah responded by sending Ali ibn Ibrahim ibn Najib al-Dawla, who Arwa appointed commander of the army.[3] The goal of Ibn Najib al-Dawla's mission is debated. According to Samer Traboulsi, he was sent to bring Arwa under closer Fatimid control. According to Husain Hamdani, on the other hand, he had been sent solely to assist her.[1]

Ibn Najib al-Dawla was able to restore Sulayhid authority over several key castles, but he was unable to retake any major cities like Aden, Sanaa, or Zabid. In 1123, the new Fatimid vizier al-Ma'mun al-Bata'ihi sent 400 Armenian archers and 700 knights to reinforce him. However, the tribal leaders loyal to Arwa were expressing "some discomfort at his presence".[3]

Meanwhile, Ibn Najib al-Dawla's victories had apparently inflated his ego, and he tried to stage a coup against Arwa and replace her as leader - he thought she was "old and feeble-minded and needed to step down".[1] Arwa quickly led a counterattack and besieged his soldiers; meanwhile, she ordered "large sums of Egyptian money to be distributed" to the tribal leaders who were on bad terms with Ibn Najib al-Dawla. She apparently spread rumors that the money had come from Ibn Najib al-Dawla himself. Ibn Najib al-Dawla's own mercenaries were upset and abandoned him, and he was forced to submit to Arwa.[1] He was arrested and kept prisoner in Dhu Jibla for an unknown length of time.[3]

The caliph al-Amir ended up recalling Ibn Najib al-Dawla. Arwa sent Ibn Najib al-Dawla back to Egypt by boat - in a wooden cage.[3] On the same boat, she sent her trusted secretary al-Azdi as an envoy to apologize to the caliph for arresting Ibn Najib al-Dawla, along with precious gifts.[3] They never made it to Egypt, as the ship sank on the way.[3][dubious – discuss] Arwa was accused of paying the ship's captain to scupper it, but according to Taef El-Azhari this is unlikely because al-Azdi was also on the ship.[3]

Religious policy

Arwa was given the highest rank in the Yemeni dawah, that of Hujjat, by Imām Al-Mustansir Billah in 1084. This was the first time that a woman had ever been given such a status in the whole history of Islam. Under her rule, Shi'ite da'is were sent to western India. Owing to her patronage of missions, an Ismāʿīlī community was established in Gujarat in the second half of the 11th century, which still survives there today as Dawoodi Bohra, Sulaymani and Alavi.[8]

In the 1094 schism, Arwa supported Al-Musta'li to be the rightful successor to Al-Mustansir Billah. Due to the high opinion in which Arwa was held in Yemen and western India, these two areas followed her in regarding Imām al-Musta'li as the new Fatimid Caliph.

Through her support of Imām at-Tāyyīb she became head of a new grouping that became known as the Taiyabi Ismaili. Her enemies in Yemen in turn gave their backing to Al-Hafiz but they were unable to remove Sayyadah Arwa from power. The Taiyabi Ismaili believe that Imām al-Āmir bi'Aḥkāmill-Lāh sent a letter to Arwa commissioning her to appoint a vicegerent for his infant son, Imām Taiyyab. In accordance with this wish, she appointed Zoeb bin Moosa as Da'i al-Mutlaq, the vicegerent of the secluded at-Tāyyīb Abū l-Qāsim. The line of succession continues down to today through the various Taiyabi Duat.

Hafizi Ismāʿīlīsm, the following of al-Hafiz, intimately tied to the Fatimid regime in Cairo, disappeared soon after the collapse of the Caliphate in 1171 and the Ayyubid invasion of southern Arabia in 1173. But the Taiyabi dawah, initiated by Arwa, survived in Yemen with its headquarters remaining in Haraz. Due to the close ties between Sulayhid Yemen and Gujarat, the Taiyibi cause was also upheld in western India and Yemen, which gradually became home to the largest population of Taiyabis, known there as Sulaymani, Dawoodi Bohra and Alavi Bohra.[citation needed]

The fact that Arwa had been chosen as hujjah necessitated theological explanations for why the infallible imam would choose a woman for this position.[6] One source is the Ghāyat al-Mawālīd by al-Sultan al-Khattab, a high-ranking da'i who played an important political and military role in the last years of Arwa's rule.[6] Al-Khattab presented an original argument - albeit one grounded in existing Isma'ili theological principles - to justify Arwa in this role.[6] According to him, a person's actual sex is not determined by the bodily "envelope" they physically have.[6] Rather, their sex can only be discerned through their actions.[6] It was possible, then, for there to be people who occupied the higher, or "male", level despite having the physical form of a woman; such as Fatimah or Khadijah.[6] Therefore, he wrote that it was unfair to consider those with a female body envelope as spiritually inferior.[6] A dhakar is spiritually perfect and has reached the highest levels of spiritual knowledge, while an unthā is on a lower level and can still progress with help of a dhakar.[6] Once reaching the highest level of religious knowledge, he would immediately become a dhakar even if having the bodily envelope of a women.[6] Arwa, he argued, had done just that since al-Mustansir's appointment of her as hujjah was because she had reached such a level of wisdom, so there was no contradiction between her sex and her rank.[6] Al-Khattab said that a person must be judged on their knowledge and not based on physical appearance.[6] Al-Khattab was basically claiming that Arwa was male in essence.[6]

Building works and economic policy

In Sana'a, Arwa had the grand mosque expanded, and the road from the city to Samarra improved.[2] In Jibla, she had a new Palace of Queen Arwa and the eponymous mosque constructed. She is also known to have built numerous schools throughout her realm. Arwa improved the economy, taking an interest in supporting agriculture.[citation needed]

Death and legacy

Arwa died in 1138 at the age of 90.[1] She was buried in the mosque that she had had built at Dhu Jibla.[1] Her tomb has since become a place of pilgrimage for Muslims of various communities, both local and foreign, although they are not always aware of her Isma'ili background.[1] The Queen Arwa University in Sana'a is named after her.[9]

With Arwa's death, the Sulayhid dynasty effectively came to an end.[1] She gave all her wealth to the Tayyibi da'wah when she died, and although some members of the Sulayhids held on to scattered fortresses in the decades after her death, they were relatively insignificant.[1]

During her own lifetime, Arwa's political role may have inspired another Yemeni woman, Alam al-Malika, to assume power as queen.[3] Alam had been the concubine of the Najahid ruler Mansur until his assassination in 1125; she then ruled as regent for her infant son Fatik.[3] Later queens in Yemen may have also been influenced by Arwa's legacy to take an active role in political affairs, such as the Ayyubid queen mother Umm al-Nasir in 1215, and later the Rasulid princess al-Dar al-Shamsi (d. 1295), who defended the Rasulid capital of Zabid after her father al-Mansur Umar died and was later made queen of Zabid by her brother al-Muzaffar Yusuf I.[3]

Fatema Mernissi has lamented that Arwa, along with her mother-in-law Asma, has remained obscure both in the Muslim world and to Western scholars.[2] Samer Traboulsi notes that, as an Isma'ili woman from Yemen, Arwa was a "triply marginalized" figure who was neglected by Muslim historians; and that if not for Ali's sack of Mecca, the medieval Islamic world would not have even heard of the Sulayhids.[6]

Personality

Historical sources "are unanimous in their praise" of Arwa's intelligence, charisma, and political acumen.[1] Idris Imad al-Din, for example, described her as "a woman of great piety, integrity, and excellence, perfect intelligence and erudition, surpassing men even".[1] Umara describes her as "well-read and, in addition to the gift of writing, [she] possessed a retentive memory stored with the chronology of past time."[1] He also described her knowledge of the Qur'an, her memory of poetry and history, and her skill in glossing and interpreting texts.[7] In modern times, Farhad Daftary has characterized Arwa as having had an independent personality.[1] Historical sources also describe her physical appearance, although Shahla Haeri wonders whether that many people would have seen her in person.[1] Umara described her as "of fair complexion tinged with red; tall, well-proportioned, but inclined to stoutness, perfect in beauty of features, with a clear-sounding voice".[1]

According to Haeri, these accounts would have relied heavily on oral tradition;[1] El-Azhari says these "are based on her later status, thus praising her personality and wide knowledge, but without providing further detail."[3]

-

Wooden Tasbih of Hurrat-ul-Malaika Arwa

-

The grave Hurratul mallika Arwa

See also

Notes

- ^ Ahmad's name is also given as "Ahmad ibn Ja'far ibn Musa al-Sulayhi", and al-Raddah's name is also given as "al-Radah bint al-Fari".[1]

- ^ Or 1069, in Umara's version[7]

- ^ According to Cortese and Calderini, however, the marriage happened while al-A'azz was still alive and he died soon after it took place, and Arwa was thus raised to "queen-consort-to-be".[7]

- ^ The Ma'nid emirs again suspended this payment after al-Mukarram Ahmad died in 1084.[7]

- ^ Muhammad's full name was al-Muzaffar Abd al-Imam Muhammad, and Ali's full name was al-Mukarram al-Asghar Abd al-Mustansir Ali.[6] The name "al-Mukarram al-Asghar" means "al-Mukarram the younger".[1]

- ^ There is some dispute about the date.[3]

- ^ This opposition may have come mainly from the large Zaydi population in Sanaa.[3]

- ^ According to Abbas Hamdani, she probably resided in the Haraz instead.[4]

- ^ Some sources, such as Umara and al-Janadi, give the date as 1091 instead, but the earlier date is confirmed by a sijill from al-Mustansir dated to 27 June 1085.[4]

- ^ Concealing the news of a ruler's death like this was historically not uncommon. It was done to try and prevent a political crisis over succession.[1]

- ^ According to Abbas Hamdani, Saba' eventually "gallantly" withdrew his offer when he realized just how much Arwa was opposed to the marriage.[4]

- ^ The ustadh was a eunuch named Yamin al-Dawla, who met Arwa at the Dhu Jibla palace in front of "all her advisors and secretaries".[3]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao Haeri, Shahla (2020), The Unforgettable Queens of Islam, Cambridge University Press, pp. 89–105, ISBN 978-1-107-55489-4

- ^ a b c d e f g Mernissi, Fatima; Lakeland, Mary Jo (translator) (2003), The forgotten queens of Islam, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-579868-5

{{citation}}:|first2=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci cj ck cl cm cn co cp cq El-Azhari, Taef (2021). Queens, Eunuchs, and Concubines in Islamic History, 661-1257 (PDF). Edinburgh University Press. pp. 196–252. ISBN 9781474423199. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Hamdani, Abbas (1974). "The dāʿī Ḥātim ibn Ibrāhīm al-Ḥāmidī (d. 596 H./ 1199 A.D.) and His Book "Tuḥfat al-qulūb"". Oriens. 23/24: 258–300. doi:10.2307/1580105. JSTOR 1580105. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Nājī, Sulṭān (1973). Bibliyūjrāfiyā Mukhtārah Wa-tafsīrīyah ʻan Al-Yaman. Kuwait University, Libraries Department. p. 184.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at Traboulsi, Samer (2003). "The Queen was Actually a Man: Arwā Bint Aḥmad and the Politics of Religion". Arabica. 50 (1): 96–108. doi:10.1163/157005803321112164. JSTOR 4057749. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Cortese, Delia; Calderini, Simonetta (2006). Women and the Fatimids in the World of Islam. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 128–40. ISBN 0-7486-1732-9. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ 15 Important Muslim Women in History, March 8, 2014

- ^ "About the name of the University". جامعة الملكة أروى.[permanent dead link]

- Sayyida Hurra. "The Ismāʿīlī Sulayhid Queen of Yemen by Farhad Daftary"; contained in the book Women in the Medieval Islamic World, edited by Gavin R. G. Hambly

- Monarchs of Yemen

- Arab queens

- Sulayhid dynasty

- 1040s births

- 1138 deaths

- Yemeni Ismailis

- Tayyibi Isma'ilism

- 11th-century queens regnant

- 11th-century women regents

- 11th-century regents

- 12th-century queens regnant

- 11th century in Yemen

- 12th century in Yemen

- 11th-century Ismailis

- 12th-century Ismailis

- 11th-century Yemeni people

- 12th-century Yemeni people

- Queens regnant in Asia