Opposition to Vladimir Putin in Russia: Difference between revisions

| Line 110: | Line 110: | ||

In October 2023, Putin's close associate [[Vyacheslav Volodin]], Speaker of the State Duma, said that Russians who "desire the victory of the murderous Nazi Kyiv regime" should be sent to the far-eastern region of [[Magadan Oblast|Magadan]], known for its Stalin-era [[Gulag]] camps, and forced to work in the mines.<ref>{{cite news |title=Returning Russians who backed Ukraine must be sent to the mines, says Putin ally |url=https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-10-12/putin-ally-says-traitorous-returnees-deserve-harsh-treatment/102966078 |work=ABC News |date=11 October 2023}}</ref> In November 2023, Volodin wrote on his Telegram channel that [[Russian emigration following the Russian invasion of Ukraine|Russians who left the country]] after the Russian invasion of Ukraine and are now returning "should understand that no one here is waiting for them with open arms" because they "committed treason against Russia".<ref>{{cite news |title=Russian State Duma speaker says ‘traitors’ who left after Ukraine invasion not welcome in Russia |url=https://meduza.io/en/news/2023/11/25/russian-state-duma-speaker-says-traitors-who-left-after-ukraine-invasion-not-welcome-in-russia |work=[[Meduza]] |date=25 November 2023}}</ref> |

In October 2023, Putin's close associate [[Vyacheslav Volodin]], Speaker of the State Duma, said that Russians who "desire the victory of the murderous Nazi Kyiv regime" should be sent to the far-eastern region of [[Magadan Oblast|Magadan]], known for its Stalin-era [[Gulag]] camps, and forced to work in the mines.<ref>{{cite news |title=Returning Russians who backed Ukraine must be sent to the mines, says Putin ally |url=https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-10-12/putin-ally-says-traitorous-returnees-deserve-harsh-treatment/102966078 |work=ABC News |date=11 October 2023}}</ref> In November 2023, Volodin wrote on his Telegram channel that [[Russian emigration following the Russian invasion of Ukraine|Russians who left the country]] after the Russian invasion of Ukraine and are now returning "should understand that no one here is waiting for them with open arms" because they "committed treason against Russia".<ref>{{cite news |title=Russian State Duma speaker says ‘traitors’ who left after Ukraine invasion not welcome in Russia |url=https://meduza.io/en/news/2023/11/25/russian-state-duma-speaker-says-traitors-who-left-after-ukraine-invasion-not-welcome-in-russia |work=[[Meduza]] |date=25 November 2023}}</ref> |

||

=== |

===2022–present Russian partisan movement=== |

||

{{main|Belarusian and Russian partisan movement (2022–present)}} |

{{main|Belarusian and Russian partisan movement (2022–present)}} |

||

In response to the invasion of Ukraine, numerous armed [[Democracy|pro-democratic]], and [[anti-authoritarianism|anti-authoritarian]] partisan and insurgent groups have sprung up within Russia in open rebellion with the aim of sabotaging the war effort and overthrowing Putin and his regime.<ref name="BelSat">{{Cite web|date=August 12, 2022|title=Коктейли Молотова и рельсовая война — стратегия новой российской оппозиции. Роман Попков поговорил с "партизанами" об их методах борьбы |trans-title=Molotov cocktails and rail war: the strategy of the new Russian opposition. Roman Popkov speaks with the "partisans" about their methods of struggle|url=https://vot-tak.tv/novosti/09-08-2022-guerrilla/|website=БелСат|language=ru}}</ref> These groups primarily engage in [[guerrilla warfare]] against the state and utilize the destruction of infrastructure such as [[Rail war in Russia (2022–present)|railways]], [[2022 Russian military commissariats attacks|military recruitment centers]], and radio towers, as well as other means to harm the state such as conducting assassinations. Some of the most notable groups involved in the conflict include the [[Combat Organization of Anarcho-Communists]] '''(BOAK)''' regarded by [[The Insider (website)|The Insider]] as "The most active 'subversive' force" within Russia since the war began,<ref name="theinsider.pro"/> the [[National Republican Army (Russia)|National Republican Army]],<ref name="Smart20220823">{{Cite web |last=Smart |first=Jason Jay |date=2022-08-23 |title=Exclusive interview: Russia's NRA Begins Activism |url=https://www.kyivpost.com/ukraine-politics/exclusive-interview-russias-nra-begins-activism.html |access-date=2023-09-18 |website=[[Kyiv Post]]|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230709232921/https://www.kyivpost.com/post/6613|archive-date=July 9, 2023}}</ref> the [[Freedom of Russia Legion]],<ref name="Glavcom">{{Cite web |date=2022-08-31 |title=Российская оппозиция начинает вооруженное сопротивление Путину: подписано декларацию |url=https://glavcom.ua/ru/news/mozhovoj-tsentr-sverzhenija-rezhima-putina-budet-dejstvovat-v-ukraine-872092.html |access-date=2023-09-18 |website=Главком {{!}} Glavcom |language=ru|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230529204433/https://glavcom.ua/ru/news/mozhovoj-tsentr-sverzhenija-rezhima-putina-budet-dejstvovat-v-ukraine-872092.html|archive-date=May 29, 2023}}</ref> and the [[far-right politics|far-right]] [[Russian Volunteer Corps]].<ref name=":2">{{Cite news |url=https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/how-russians-end-up-far-right-militia-fighting-ukraine-2023-05-11/ |title=How Russians end up in a far-right militia fighting in Ukraine |website=[[Reuters]]|date=11 May 2023 |last1=Pikulicka-Wilczewska |first1=Agnieszka |last2=Pikulicka-Wilczewska |first2=Agnieszka }}</ref> |

In response to the invasion of Ukraine, numerous armed [[Democracy|pro-democratic]], and [[anti-authoritarianism|anti-authoritarian]] partisan and insurgent groups have sprung up within Russia in open rebellion with the aim of sabotaging the war effort and overthrowing Putin and his regime.<ref name="BelSat">{{Cite web|date=August 12, 2022|title=Коктейли Молотова и рельсовая война — стратегия новой российской оппозиции. Роман Попков поговорил с "партизанами" об их методах борьбы |trans-title=Molotov cocktails and rail war: the strategy of the new Russian opposition. Roman Popkov speaks with the "partisans" about their methods of struggle|url=https://vot-tak.tv/novosti/09-08-2022-guerrilla/|website=БелСат|language=ru}}</ref> These groups primarily engage in [[guerrilla warfare]] against the state and utilize the destruction of infrastructure such as [[Rail war in Russia (2022–present)|railways]], [[2022 Russian military commissariats attacks|military recruitment centers]], and radio towers, as well as other means to harm the state such as conducting assassinations. Some of the most notable groups involved in the conflict include the [[Combat Organization of Anarcho-Communists]] '''(BOAK)''' regarded by [[The Insider (website)|The Insider]] as "The most active 'subversive' force" within Russia since the war began,<ref name="theinsider.pro"/> the [[National Republican Army (Russia)|National Republican Army]],<ref name="Smart20220823">{{Cite web |last=Smart |first=Jason Jay |date=2022-08-23 |title=Exclusive interview: Russia's NRA Begins Activism |url=https://www.kyivpost.com/ukraine-politics/exclusive-interview-russias-nra-begins-activism.html |access-date=2023-09-18 |website=[[Kyiv Post]]|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230709232921/https://www.kyivpost.com/post/6613|archive-date=July 9, 2023}}</ref> the [[Freedom of Russia Legion]],<ref name="Glavcom">{{Cite web |date=2022-08-31 |title=Российская оппозиция начинает вооруженное сопротивление Путину: подписано декларацию |url=https://glavcom.ua/ru/news/mozhovoj-tsentr-sverzhenija-rezhima-putina-budet-dejstvovat-v-ukraine-872092.html |access-date=2023-09-18 |website=Главком {{!}} Glavcom |language=ru|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230529204433/https://glavcom.ua/ru/news/mozhovoj-tsentr-sverzhenija-rezhima-putina-budet-dejstvovat-v-ukraine-872092.html|archive-date=May 29, 2023}}</ref> and the [[far-right politics|far-right]] [[Russian Volunteer Corps]].<ref name=":2">{{Cite news |url=https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/how-russians-end-up-far-right-militia-fighting-ukraine-2023-05-11/ |title=How Russians end up in a far-right militia fighting in Ukraine |website=[[Reuters]]|date=11 May 2023 |last1=Pikulicka-Wilczewska |first1=Agnieszka |last2=Pikulicka-Wilczewska |first2=Agnieszka }}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 12:31, 19 February 2024

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Russian. (January 2013) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

|

|---|

Opposition to the government of President Vladimir Putin in Russia, commonly referred to as the Russian opposition, can be divided between the parliamentary opposition parties in the State Duma and the various non-systemic opposition organizations. While the former are largely viewed as being more or less loyal to the government and Putin,[1][2] the latter oppose the government and are mostly unrepresented in government bodies. According to Russian NGO Levada Center, about 15% of the Russian population disapproved of Putin in the beginning of 2023.[3][4]

The "systemic opposition" is mainly composed of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (KPRF), the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR), A Just Russia – For Truth (SRZP), New People and other minor parties; these political groups, while claiming to be in opposition, generally support the government's policies.[5][6]

Major political parties considered to be part of the non-systemic opposition include Yabloko and the People's Freedom Party (PARNAS), along with the unregistered party Russia of the Future and Libertarian Party of Russia (LPR). Other notable opposition groups included the Russian Opposition Coordination Council (KSO) (2012–2013) and The Other Russia (2006–2011), as well as various non-governmental organizations (NGOs).[5]

Their supporters vary in political ideology, ranging from liberals, socialists, and anarchists, to Russian nationalists. They are mainly unified by their opposition to Putin and government corruption. However, a lack of unity within the opposition has also hindered its standing.[7][8][9] Opposition figures claim that a number of laws have been passed and other measures taken by Putin's government to prevent them from having any electoral success.

Background and composition

The Guardian's report from Luke Harding noted that during the 2000s Neo-Nazis, Russian nationalists, and ultranationalist groups were the most significant opposition to Putin's government.[10]

Some observers noted what they described as a "generational struggle" among Russians over perception of Putin's rule, with younger Russians more likely to be against Putin and his policies and older Russians more likely to accept the narrative presented by state-controlled media in Russia. Putin's approval rating among young Russians was 32% in January 2019, according to the Levada Center.[11] Another poll from the organization placed Putin's support among Russians aged 18–24 at 20% in December 2020.[12]

Actions and campaigns

Current campaigns of the opposition include the dissemination of anti-Putin reports such as Putin. Results. 10 years (2010), Putin. Corruption (2011) and Life of a Slave on Galleys (2012). Video versions of these reports, entitled Lies of Putin's regime,[13] have been viewed by about 10 million times on the Internet.[14]

In addition, smaller-scale series of actions are conducted. For example, in Moscow in the spring of 2012 saw a series of flash mobs "White Square", when protesters walked through the Red Square with white ribbons,[15] in the late spring and summer, they organized the protest camp "Occupy Abay" and autumn they held weekly "Liberty walks" with the chains symbolizing solidarity with political prisoners.[16]

A monstration is a parody demonstration where participants gently poke fun at Kremlin policies.[17]

Participation in elections

Some opposition figures, for example, chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov, said there are no elections in Putin's Russia,[18][19] and that participation in a procedure called elections only legitimizes the regime.[citation needed]

On the other hand, a small part of liberals (the party of "Democratic Choice") consider elections as the main tool to achieve their political goals.[20]

History

2006–2008 Dissenters' March

The Dissenters' March was a series of Russian opposition protests started in 2006. It was preceded by opposition rallies in Russian cities in December 2005 which involved fewer people. Most of the Dissenters' March protests were unsanctioned by authorities. The Dissenters' March rally was organized by The Other Russia, a broad umbrella group that includes opposition leaders, including National Bolshevik Party with its leader Eduard Limonov, far-left Vanguard of Red Youth as well as liberals such as former world chess champion and United Civil Front leader Garry Kasparov.

2009–2011 Strategy-31

Strategy-31 was a series of civic protests in support of the right to peaceful assembly in Russia guaranteed by Article 31 of the Russian Constitution. Since 31 July 2009, the protests were held in Moscow on Triumfalnaya Square on the 31st of every month with 31 days.[21] Strategy-31 was led by writer Eduard Limonov and human rights activist Lyudmila Alexeyeva.

2011–2013 Russian protests

Starting from 5 December 2011, the day after the elections to the State Duma, there have been repeated massive political actions of Russian citizens who disagree with the outcome of these "elections". The current surge of mass opposition rallies has been called in some publications "a snow revolution".[22][23][24][25] These rallies continued during the campaign for the election of the President of Russia and after 4 March 2012, presidential election, in which Putin officially won the first round. The protesters claimed that the elections were accompanied by violations of the election legislation and widespread fraud. One of the main slogans of the majority of actions was "For Fair Elections!" and a white ribbon has been chosen as symbol of protests. Beginning from spring 2012 the actions were called marches of millions and took the form of a march followed by a rally. The speeches of participants were anti-Putin and anti-government.

The "March of Millions" on 6 May 2012 at the approach to Bolotnaya Square was dispersed by the police. In the Bolotnaya Square case 17 people are accused of committing violence against police (12 of them are in jail). A large number of human rights defenders and community leaders have declared the detainees innocent and the police responsible for the clashes.[26][27]

For the rally on 15 December 2012, the anniversary of the mass protests against rigged elections, the organizers failed to agree with the authorities, and participation was low. Several thousand people gathered without placards on Lubyanka Square and laid flowers at the Solovetsky Stone.[28]

2014 anti-war protests

In 2014, members of the Russian opposition have held anti-war protests in opposition to the Russian military intervention in Ukraine in the aftermath of the 2014 Ukrainian revolution and Crimean crisis. The March of Peace protests took place in Moscow on 15 March, a day before the Crimean status referendum. The protests have been the largest in Russia since the 2011 protests. Reuters reported that 30,000 people participated in 15 March anti-war rally.[29]

2017–2018 Russian protests

On 26 March 2017, protests against alleged corruption in the Russian government took place simultaneously in many cities across the country. The protests began after the release of the film He Is Not Dimon to You by Alexei Navalny's Anti-Corruption Foundation. An April 2017 Levada poll found that 45% of surveyed Russians supported the resignation of Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev,[30] against it 33% of respondents. Newsweek reported that "An opinion poll by the Moscow-based Levada Center indicated that 38 percent of Russians supported the rallies and that 67 percent held Putin personally responsible for high-level corruption."[31]

A May 2017 Levada poll found that 58% of surveyed Russians supported the protests, while 23% said they disapprove.[32]

2018 Russian pension protests

From July 2018, almost every weekend, protest rallies and demonstrations were organized against the planned retirement age hike. Such events occurred in nearly all major cities countrywide including Novosibirsk, St.-Petersburg and Moscow. These events were coordinated by all opposition parties with the leading role of the communists. Also trade unions and some individual politicians (among whom Navalny) functioned as organizers of the public actions.[33]

An intention to hike the retirement age has drastically downed the rating of the President Vladimir Putin and Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev in Russia. So in July 2018, just 49% would vote for Putin if the presidential elections were held in that moment (while during the elections in March 2018, he got 76.7%).[34][35]

2019 Russian protests

In the first half of 2019 there were approximately 863 protests across the country.[36]

From July 2019, protest rallies for an access to 2019 Moscow City Duma election of independent candidates started in Moscow. The 20 July rally was the largest since 2012. The 27 July rally set a record in number of detainees and police violence.[37][38] The 10 August rally outnumbered the 27 July rally, oppositional sources report 50–60 thousand participants.[39]

2020–21 Khabarovsk Krai protests

On 9 July 2020, the popular governor of the Khabarovsk Krai, Sergei Furgal, who defeated the candidate of Putin's United Russia party in elections two years ago, was arrested and flown to Moscow. Furgal was arrested 15 years after the alleged crimes he is accused of. Every day since 11 June, mass protests have been held in the Khabarovsk Krai in support of Furgal.[40] On 25 July, tens of thousands of people were estimated to have taken part in the third major rally in Khabarovsk.[41] The protests included chants of "Away with Putin!", "This is our region", "Furgal was our choice" or "shame on LDPR" and "Shame on the Kremlin!"[41][42][43]

In a Levada Center poll carried out from 24 to 25 July 2020, 45% of surveyed Russians viewed the protests positively, 26% neutrally and 17% negatively.[44]

2021 Russian protests

On 23 January 2021, protests across Russia were held in support of the Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny, who was detained and then jailed after returning to Russia on 17 January following his poisoning. A few days before the protests, an investigation by Navalny and his Anti-Corruption Foundation was published, accusing Putin of corruption. The video garnered 70 million views in a few days.[45]

Since jailing of Navalny a "hardening of the course" was observed from the government side, with a choice of "go West or East" being offered to prominent opposition figures, meaning a non-negotiable alternative of either going on emigration ("West") or to prison colonies ("East"). Among those who left Russia are politicians Lyubov Sobol, Dmitry Gudkov, Ivan Zhdanov (whose father had been however arrested in Russia as a hostage), Kira Yarmysh, journalists Andrei Soldatov, Irina Borogan, Roman Badanin. The wave of repressions has been also linked with the September 2021 Duma elections.[46][47]

2021 Russian election protests

Protests against alleged large-scale fraud in favour of the ruling party were held.[48]

2022 anti-war protests

Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, protesters have used the white-blue-white flag as a symbol of opposition though not all used the flag. Several opposition activists (such as Maria Motuznaya) had criticized the justification by AssezJeune (one of the creators of the flag) to remove the red stripe.[49]

On the afternoon of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Investigative Committee of Russia issued a warning to Russians that they would face legal repercussions for joining unsanctioned protests related to "the tense foreign political situation".[50] The protests have been met with widespread repression by the Russian authorities. According to OVD-Info, at least 14,906 people were detained from 24 February to 13 March,[51][52] including the largest single-day mass arrests in post-Soviet Russian history on 6 March.[53]

In February 2022, more than 30,000 technology workers,[54] 6,000 medical workers, 3,400 architects,[55] more than 4,300 teachers,[56] more than 17,000 artists,[57] 5,000 scientists,[58] and 2,000 actors, directors, and other creative figures signed open letters calling for Putin's government to stop the war.[59][60] Some Russians who signed petitions against Russia's war in Ukraine lost their jobs.[61]

On 17 March, Putin gave a speech in which he called opponents of the war "scum and traitors," saying that a "natural and necessary self-cleansing of society will only strengthen our country."[62][63] Russian authorities were encouraging Russians to report their friends, colleagues and family members to the police for expressing opposition to the war in Ukraine.[64]

More than 2,000 people were detained or fined by May 2022 under the laws prohibiting "fake" information about the military.[65] In July 2022, Alexei Gorinov, a member of the Krasnoselsky district council in Moscow, was sentenced to seven years in prison after making anti-war comments at a council meeting in March.[66] Lawyer Pavel Chikov said that this was the first jail term under the new Russian 2022 war censorship laws.[67] According to Amnesty International, as of June 2023, up to 20,000 Russian citizens had been subject to heavy reprisals for opposing the war in Ukraine.[68]

In October 2023, Putin's close associate Vyacheslav Volodin, Speaker of the State Duma, said that Russians who "desire the victory of the murderous Nazi Kyiv regime" should be sent to the far-eastern region of Magadan, known for its Stalin-era Gulag camps, and forced to work in the mines.[69] In November 2023, Volodin wrote on his Telegram channel that Russians who left the country after the Russian invasion of Ukraine and are now returning "should understand that no one here is waiting for them with open arms" because they "committed treason against Russia".[70]

2022–present Russian partisan movement

In response to the invasion of Ukraine, numerous armed pro-democratic, and anti-authoritarian partisan and insurgent groups have sprung up within Russia in open rebellion with the aim of sabotaging the war effort and overthrowing Putin and his regime.[71] These groups primarily engage in guerrilla warfare against the state and utilize the destruction of infrastructure such as railways, military recruitment centers, and radio towers, as well as other means to harm the state such as conducting assassinations. Some of the most notable groups involved in the conflict include the Combat Organization of Anarcho-Communists (BOAK) regarded by The Insider as "The most active 'subversive' force" within Russia since the war began,[9] the National Republican Army,[72] the Freedom of Russia Legion,[73] and the far-right Russian Volunteer Corps.[74]

2023 Wagner rebellion

On June 23, 2023, forces loyal to Yevgeny Prigozhin's Wagner Group began a mutiny against the Russian government. Citing the Russian Ministry of Defence's, and namely the Russian Minister of Defense, Sergei Shoigu's mishandling of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, as well as claiming the Russian army shelled one of the Wagner group's barracks, resulting in casualties. Wagner occupied the city of Rostov-on-Don, surrounding and then seizing the headquarters of the Southern Military District. Prigozhin vowed to march on Moscow and arrest Shoigu, and other Russian generals, and put them on trial for murder of Wagner personnel.[75][needs update]

There were no sizeable spontaneous displays of public support for the Putin government during the rebellion.[76] The Russian population displayed a predominantly "silent" and apathetic reaction.[77][78] Russia analyst Anna Matveeva contrasted the Russian public's response to that of the Turkish public during the 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt, where numerous Turkish citizens actively participated in anti-coup demonstrations.[79]

2024 Russian presidential election

Under the previous rules, Putin would have had to have stood down as president in 2024 due to term limits in Russia's constitution,[80][81] but it was widely expected that he would attempt to stay in power through certain means such as changing the constitution, even though Putin claimed in 2018 that he wouldn't.[82][83][80] Subsequently, Putin announced that constitutional changes would be proposed allowing him to stay in power until 2036 by "resetting" his terms, widely criticised by opponents, and these changes were then 'approved' in a referendum in which independent election monitors received hundreds of reports of violations and employees who were paid by the state such as teachers, doctors and public sector workers were deliberately prompted to vote in favour.[84][80][81] Leader of the opposition Alexei Navalny dismissed the legitimacy of the poll and denounced the changes, saying that they would make Putin "president for life".[84] The changes meant that Putin could now officially run in the 2024 Russian presidential election, and he announced he would do so.[85]

Journalist Yekaterina Duntsova tried to run in the 2024 election, saying she would run on an platform opposing the war in Ukraine and commenting: "Any sane person taking this step would be afraid - but fear must not win".[85][86] However, only three days after her application, she was barred from running by the Central Election Commission, who claimed that she had made '100 mistakes' on her forms and barred her from even collecting signatures to start her campaign.[85][87] The BBC reported on Dunstova's rejection that: "the immediate slap-down of a Putin critic will be seen as evidence by some that no dissent will be tolerated in the campaign".[85] Another individual who attempted to become a candidate, the nationalist pro-war blogger Igor Girkin, openly declared that the election was a "sham", stating that "the only winner is known in advance" and "I understand perfectly well that in the current situation in Russia, participating in the presidential campaign is like sitting down at a table to play with card sharps".[85][88] Girkin, a former FSB agent and a Putin critic, was later sentenced to four years imprisonment.[89]

In late January 2024, a source in the Putin administration told the Latvia-based news outlet Meduza: "There’s a portion of the electorate that wants the war to end. If [Putin’s opponent in the elections] decides to cater to this demand, they may get a decent percentage. And [the Putin administration] doesn’t need that."[90]

Boris Nadezhdin declared his intention to run on a platform of opposing Putin and the Ukraine war.[91][92] He quickly gained support, and queues formed in towns and villages across Russia and outside Boris Nadezhdin’s headquarters in Moscow to sign their name in support of his bid for presidency.[93][94][92] Footage showed how many thousands had queued even in the snow to sign their names, and he garnered "surprise levels of support".[92][95][96][97] Nadezhdin proved particularly popular with younger urban Russians.[95] The number of Russians who had turned up to sign their names was so unexpectedly high that extra sign-up centres had to be added in Moscow.[96] NBC News said that the fact that Nadezhdin had managed to collect more than 100,000 signatures to support his campaign was "no small feat for a candidate who says his campaign is funded exclusively by crowdfunding".[97]

In what was described as something "seemingly unachievable in Russian politics"[97], Nadezhdin managed to unify many prominent opposition politicians and public figures behind his campaign and gained their endorsements: Yekaterina Duntsova (who had previously been barred[98][99]), Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Ekaterina Schulmann, Yulia Navalnaya (wife of Alexei Navalny), Ilya Varlamov, Lyubov Sobol and many others.[100][101][102][103] Russia's main opposition leader Navalny also passed a message from his imprisonment giving his backing to Nadezhdin's campaign.[92] Navalny had himself been barred from the previous Russian presidential election in 2018 on what is widely seen as political grounds.[92]

In January 2024, citing unidentified sources in the Kremlin, the independent news outlet Vyorstka reported that the CEC, at the behest of the Kremlin, would likely reject Nadezhdin’s registration due to his criticism of Putin and anti-war stances.[104] The CEC regularly uses the process of having to collect signatures to refuse to register would-be opposition candidates, acting as a form of filter to stop unwanted developments for the Kremlin.[105] It was already widely thought that authorities would not welcome a candidate who is openly anti the war in Ukraine.[106] On 30 January 2024, Kremlin propagandist and television presenter Vladimir Solovyov warned Nadezhdin: "I feel bad for Boris. The fool didn’t realize that he’s not being set up to run for president but for a criminal case on charges of betraying the Motherland."[90]

On 8 February 2024, Nadezhdin was barred from running due to alleged "irregularities" in the signatures of voters supporting his candidacy.[107] The election commission claimed that only 95,587 of his signatures in support of his candidacy were valid, just short of the 100,000 needed to run.[92] His team said that some of the "errors" the election commission had claimed existed were merely minor typos that happened when handwritten names were put into its computers.[108]

From prison, Alexei Navalny, as well as his allies, had called on supporters to protest Putin and the invasion of Ukraine during the third day of the presidential election by all going to vote against Putin at the same time.[109] Navalny then died in suspicious circumstances in his harsh imprisonment at a prison colony in the Arctic Circle, aged only 47, on 16 February 2024.[110][111] After his death, Russians began bringing flowers to monuments to victims of political repression in cities across the country.[112] People laid flowers at Moscow’s Solovetsky Stone and the Wall of Grief.[113] The Moscow Prosecutor’s Office warned Russians against mass protests.[114]

Opposition figures

- Zhanna Agalakova[115][116]

- Liya Akhedzhakova[117][118]

- Malik Akhmedilov[119]* †

- Georgy Alburov[120]

- Lyudmila Alexeyeva[121]*[a]

- Maria Alyokhina[122]

- Maximilian Andronikov, a.k.a. "Caesar"[123]*[b]

- Vladimir Ashurkov[124]

- Ilya Azar[125]

- Farid Babayev[126]*†

- Anastasia Baburova[127]* †

- Mikhail Beketov[128]* †

- Nikita Belykh[129]*[c]

- Boris Berezovsky[130]* †[d]

- Darya Besedina[131]

- Nikolai Bondarenko[132]

- Dmitry Bykov[133]*[e]

- Yuriy Chervochkin[134]* †

- Alexei Devotchenko[135]* †

- Roman Dobrokhotov[136]*[f]

- Yury Dud[137]*[g]

- Yekaterina Duntsova[138]

- Natalya Estemirova[127]* †

- Sergei Furgal[132]*[h]

- Maria Gaidar[139]*[i]

- Yegor Gaidar[140]*[j] †

- Maxim Galkin[141]*[k]

- Igor Girkin[142][143]*[l]

- Nikolai Glushkov[145]* †

- Alexei Gorinov[146]*[m]

- Dmitry Gudkov[125]*[n]

- Gennady Gudkov[147]*[n]

- Andrey Illarionov[148]*[n]

- Vladimir Kara-Murza[149]*[o]

- Nadezhda Karpova[150]*[p]

- Garry Kasparov[151]*[n]

- Mikhail Kasyanov[152]*[q]

- Maxim Katz[153]

- Irina Khakamada[154]

- Mikhail Khodorkovsky[149]*[n]

- Pavel Khodorkovsky[155]*[n]

- Andrei Kozyrev[156]*[n]

- Nina L. Khrushcheva[157]*[n]

- Timur Kuashev[158]* †

- Alexander Litvinenko[127]* †

- Marina Litvinenko[159]

- Mikhail Lobanov[160]

- Ravil Maganov[161]* †

- Sergei Magnitsky[127]* †

- Mikhail Matveyev[162][163][164][165]

- Stanislav Markelov[127]* †

- Boris Mints[166]*[r]

- Sergey Mitrokhin[167]

- Sergey Mokhnatkin[168]* †

- Dmitry Muratov[169]

- Boris Nadezhdin[170]

- Yulia Navalnaya[171]

- Alexei Navalny[172]* †

- Boris Nemtsov[173]* †

- Zhanna Nemtsova[174]*[s]

- Oleg Orlov[175][176]

- Marina Ovsyannikova[177]*[t]

- Oxxxymiron[179][180][181]*[u]

- Leonid Parfyonov[182]

- Dmitry Petrov[183]* †

- Nikolay Platoshkin[184]*[v]

- Anna Politkovskaya[140]* †

- Ilya Ponomarev[185]*[n]

- Lev Ponomaryov[186]

- Yevgeny Prigozhin[187]* †

- Mikhail Prokhorov[188][189]*[w]

- Valery Rashkin[190][191]

- Yevgeny Roizman[149]*[x]

- Ivan Rybkin[192]*[y]

- Vladimir Ryzhkov[193][194]

- Yekaterina Samutsevich

- Ekaterina Schulmann[195]*[z]

- Viktor Shenderovich[196]*[aa]

- Yuri Shevchuk[197]

- Lev Shlosberg[198]

- Ruslan Shaveddinov[120]*[ab]

- Yuri Shchekochikhin[127]* †

- Yury Shutov[199]* †

- Natalya Sindeyeva[200]

- Aleksandra Skochilenko[201]*[ac]

- Emilia Slabunova[202]

- Irina Slavina*[203] †

- Olga Smirnova[204]*[ad]

- Fyodor Smolov[205]

- Ksenia Sobchak[206][207]

- Lyubov Sobol[120]*[ae]

- Vladimir Sviridov

- Nadya Tolokonnikova

- Sergei Tretyakov[208]* †

- Anastasia Udaltsova[209]

- Sergei Udaltsov[209]

- Yevgeny Urlashov[210]*[af]

- Denis Voronenkov[127]* †

- Alexei Venediktov[211]*[ag]

- Pyotr Verzilov[212]*[ah]

- Kira Yarmysh[120]*[n]

- Ilya Yashin[125]*[ai]

- Grigory Yavlinsky[213]

- Magomed Yevloyev[214]* †

- Sergei Yushenkov[127]* †

- Akhmed Zakayev[215]*[n]

- Ivan Zhdanov[120]*[n]

Symbols

In 2012, the term white ribbon opposition was applied to the protesters for fair elections as they wore white ribbons as their symbol.[15]

The white-blue-white flag is a symbol of opposition to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine that has been used by Russian anti-war protesters. It has also been used as a symbol of opposition to the current government of Russia.

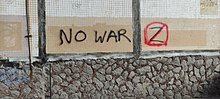

During the Wagner Group mutiny, forces loyal to the Wagner group painted a red Z on the side of their vehicles, in reference to the white Z used by Russian forces during the invasion of Ukraine.[216]

In culture

Books

- 12 Who Don't Agree (2009), non-fiction book by Valery Panyushkin

- Winter is Coming (2015), non-fiction book by former Russian chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov

Films

- Les Enfants terribles de Vladimir Vladimirovitch Poutine (2006)

- This is Our City (2007), by Alexander Shcherbanosov

- The Revolution That Wasn't (2008), by Alyona Polunina

- Term (2018), by Alexander Rastorguyev

- Putin's Palace: History of the World's Largest Bribe (2021), by Alexei Navalny

- Navalny (2022), by Daniel Roher

See also

- 2022–2023 Belarusian and Russian partisan movement

- Assassination of Boris Nemtsov

- Belarusian opposition

- Democracy movements of China

- Dissenters' March

- Kazakh opposition

- Kirill Serebrennikov

- National Endowment for Democracy

- Non-system opposition

- Political groups under Vladimir Putin's presidency

- Reaction of Russian intelligentsia to the 2014 annexation of Crimea

- Russia under Vladimir Putin

- "Russia will be free"

Notes

- ^ Died in 2018

- ^ Currently fighting in Ukraine

- ^ Since 2018 has been imprisoned

- ^ In exile since 2000, subject to an Interpol Red Notice by the Russian government, found dead in mysterious circumstances in 2013

- ^ Survived a suspected poisoning in 2019

- ^ In exile since 2021, warrant for his arrest issued by Russian government

- ^ In exile since 2022, designated a "foreign agent" by the Russian government

- ^ Since 2020 has been imprisoned

- ^ Currently lives abroad

- ^ Survived a poisoning in 2006, died unexpectedly at 53 in 2009

- ^ In exile since 2022, designated a "foreign agent" by the Russian government

- ^ Sentenced to four years imprisonment in a penal colony in 2024 for insulting Putin[144]

- ^ Sentenced to seven years' imprisonment in 2022 for objecting to the Russian Invasion of Ukraine[146]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Currently in exile

- ^ Survived poisoning by FSB agents in 2015 and 2017, imprisoned since 2022

- ^ Currently lives abroad

- ^ In exile since 2022

- ^ Currently in exile, arrest warrant issued by the Russian government

- ^ Currently in exile

- ^ In exile since 2023, sentenced to 8.5 years imprisonment in absentia for "spreading knowingly false information"[178]

- ^ Designated a "foreign agent" by the Russian government

- ^ Issued a five-year suspended prison sentence in 2021

- ^ Currently lives abroad

- ^ Since 2022 has been imprisoned

- ^ Survived a kidnapping in 2004

- ^ Currently in exile, designated a "foreign agent" by the Russian government

- ^ In exile since 2022

- ^ Designated a "foreign agent" by the Russian government, warrant for his arrest also issued

- ^ Sentenced to seven years imprisonment in 2023 for replacing five price tags in a local supermarket with notes criticising the Russian invasion of Ukraine

- ^ In exile since 2022

- ^ Currently in exile, warrant for her arrest issued by Russian government

- ^ Imprisoned since 2017

- ^ Labelled a "foreign agent" by the Russian Government in 2022

- ^ Survived a poisoning in 2017

- ^ Since 2022 has been imprisoned

References

- ^ Ben Noble, Putin just won a supermajority in the Duma. That matters. Archived 28 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Washington Post (1 October 2016): "During the 2011-2016 parliamentary session, the Kremlin often engineered supermajorities with votes from loyal opposition Duma deputies."

- ^ Thomas F Remington, Presidential Decrees in Russia: A Comparative Perspective (Cambridge University Press, 2014), p. 44: "The 'within-system' opposition parties, such as the communists and A Just Russia, must be willing to play their prescribed role as tame, domesticated versions of a real opposition."

- ^ "Indicators". Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- ^ "Putin's approval rating ends 2022 at 81%, boosted by support for the war in Ukraine". www.intellinews.com. 2 January 2023. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- ^ a b Ros, Cameron (3 March 2016). Systemic and Non-Systemic Opposition in the Russian Federation: Civil Society Awakens?. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 9781317047230. Archived from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ The Russian Awakening (PDF). Washington DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. 2012. p. 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 November 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ Peter Finn, Infighting Fractures Russian Opposition: Kremlin's Democratic Foes Help Marginalize Themselves With Suspicions, Old Feuds Archived 25 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Washington Post (28 March 2007).

- ^ A fourth term for Russia's perpetual president Archived 27 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine, The Economist (19 March 2018): "a fractured opposition."

- ^ a b Zemlyanskaya, Alisa (5 July 2022). "Этот поезд в огне: как российские партизаны поджигают военкоматы и пускают поезда под откос". The Insider (in Russian). Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ "Putin's worst nightmare". The Guardian. 8 February 2009. Archived from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ "Opinion: How Putin and the Kremlin lost Russian youths". The Washington Post. 17 June 2019. Archived from the original on 14 September 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ "Vladimir Putin's popularity with young Russians plummeting, opinion poll finds". The Times. 11 December 2020. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ "Ложь путинского режима". YouTube. Archived from the original on 23 July 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ^ b_nemtsov (10 November 2012). "Ролики "Ложь путинского режима"". Archived from the original on 24 November 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ a b "Стой! Кто идет?". www.kasparov.ru. Archived from the original on 22 April 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "Грани.Ру: В Москве задержаны участники "Прогулки свободы"". graniru.org. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "Moscow threatens to block BBC Russian service Service". Z News. 5 August 2014. Archived from the original on 4 May 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ^ Соколов, Михаил (6 June 2011). ""Выборов, которые приведут к отстранению Путина от власти, в России быть не может. Надо четко зафиксировать наш призыв к демонтажу существующей системы. Она убивает будущее России. Выживание путинского режима – это гибель страны. Вот об этом надо говорить, а не соблазнять людей предвыборными пустышками"". Радио Свобода. Archived from the original on 22 April 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "Грани.Ру | Юрий Староверов: Марш регионов вместо иллюзий". graniru.org. Archived from the original on 22 April 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "О нас. Что такое "Демократический выбор"?". Демократический выбор. Archived from the original on 18 April 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- ^ Toepfl, Florian (April 2013). "Making sense of the news in a hybrid regime: how young Russians decode state TV and an oppositional blog" (PDF). Journal of Communication. 63 (4): 244–265. doi:10.1111/jcom.12018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- ^ "Ежедневный Журнал: Координационный совет накануне выборов". ej.ru. Archived from the original on 8 June 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "Высокий градус русской зимы". Газета.Ru. Archived from the original on 12 June 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ Андерс Аслунд. Урок для России. Снежная революция не должна повторить ошибки Оранжевой. — KyivPost, 22.02.2012 Archived 13 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Протест против Путина: "снежная революция" в России тает". www.inopressa.ru. Archived from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "За права человека". За права человека. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "Грани.Ру: В Москве прошел митинг в поддержку "узников Болотной"". graniru.org. Archived from the original on 31 May 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "Стояние у Соловецкого камня: Итоги запрещенной оппозиционной акции". Archived from the original on 17 December 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "Ukraine crisis triggers Russia's biggest anti-Putin protest in two years". Reuters. 15 March 2014. Archived from the original on 7 June 2022. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ^ "Russian Polls Do Mean Something After All Archived 26 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine". Bloomberg. 26 April 2017.

- ^ "Alexei Navalny: Is Russia's Anti-Corruption Crusader Vladimir Putin's Kryptonite? Archived 12 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine". Newsweek. 17 April 2017.

- ^ "Акции протеста 12 июня Archived 4 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine". Levada Center. 13 June 2017

- ^ J. Heintz (28 July 2018). "Tens of thousands of Russians protest retirement age hikes". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on 8 June 2022. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ S. Walker (16 July 2018). "Successful World Cup fails to halt slide in Vladimir Putin's popularity". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ R. Dobrokhotov (13 July 2018). "Why Putin's approval rating is falling". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 4 May 2022. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ "Russian Officials Appear Unable to Suppress Protests". VOA News. 7 October 2019. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ Nechepurenko, Ivan (27 July 2019). "Moscow Police Arrest More Than 1,300 at Election Protest". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ "Thousand arrests at Moscow election protest". 27 July 2019. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ "Митинг на проспекте Сахарова собрал, по данным источников "Эха Москвы", от 50 до 60 тысяч человек". Эхо Москвы (in Russian). Archived from the original on 10 August 2019. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- ^ "Anti-Putin Protests in Russia's Far East Gather Steam". VOA News. 25 July 2020. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Protests Swell in Russia's Far East in a Stark New Challenge to Putin". The New York Times. 25 July 2020. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ "Anger at Kremlin Grows in Latest Massive Russian Far East Protest". The Moscow Times. 25 July 2020. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ "Anti-Kremlin protests in Khabarovsk: 'We hate Moscow!'". Deutsche Welle. 26 July 2020. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ "45 Percent of Russians Support Anti-Putin Protests While Just 17 Percent Oppose Demonstrations: Poll". Newsweek. 28 July 2020. Archived from the original on 18 September 2020. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ "Protests for Jailed Kremlin Critic Navalny Sweep Russia". The Moscow Times. 23 January 2021. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ Troianovski, Anton; Matsnev, Oleg (30 August 2021). "Exile or Jail: The Grim Choice Facing Russian Opposition Leaders". The New York Times. Moscow. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ "Navalny's spokeswoman Kira Yarmysh has fled Russia, reports Interfax". Meduza. Archived from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ "В центре Москвы прошла акция КПРФ против результатов выборов. Перед ее началом полиция взяла в осаду сторонников коммунистов — в горкоме партии и Мосгордуме". Meduza (in Russian). Archived from the original on 25 September 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ^ "У антивоенного движения появился новый символ протеста — бело-сине-белый флаг. "Медуза" рассказывает, кто и зачем его придумал". Meduza. 14 March 2022. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ "Moscow Warns Russians Against Staging Anti-War Protests". Voice of America. 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022.

- ^ Нет войне – Как российские власти борются с антивоенными протестами [No to war – How Russian authorities are fighting anti-war protests]. OVD Info (in Russian). Archived from the original on 22 March 2022. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ Shevchenko, Vitaly (15 March 2022). "Ukraine war: Protester exposes cracks in Kremlin's war message". BBC News. Archived from the original on 15 March 2022.

- ^ Vladimirova, Alexandra (14 April 2022). "Closed Shops, Zs, Green Ribbons: Russia's Post-Invasion Reality". The Moscow Times. Archived from the original on 20 April 2022. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ "Scores of IT workers in Russia sign public anti-war petition". TechCrunch. 1 March 2022. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Anti-war sentiment grows in Russia as troops close in on Ukrainian capital". PBS. 26 February 2022. Archived from the original on 27 February 2022.

- ^ "The Kremlin forces schools and theaters to uphold Putin's invasion propaganda". Coda Media. 1 March 2022. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Nearly 20,000 Russian artists are demanding a withdrawal from Ukraine". Quartz. 2 March 2022. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Global research community condemns Russian invasion of Ukraine". Nature. 1 March 2022. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Russian Government Orders Media Outlets To Delete Stories Referring To 'Invasion' Or 'Assault' On Ukraine". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, RFE/RL. 26 February 2022. Archived from the original on 27 February 2022.

- ^ "Russia's anti-war lobby goes online". France 24. 26 February 2022. Archived from the original on 27 February 2022.

- ^ "She Signed an Open Letter Calling for Peace. Then Got Fired". The Moscow Times. 3 March 2022. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022.

- ^ "Putin warns Russia against pro-Western 'traitors' and scum". Reuters. 16 March 2022. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ "Putin says Russia must undergo a 'self-cleansing of society' to purge 'bastards and traitors' as thousands flee the country". Business Insider. 16 March 2022. Archived from the original on 22 March 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ "Russians Are Snitching On Friends and Family Who Oppose the War in Ukraine". Vice. 8 August 2022. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ "Video shows defiant Russian audience chanting 'fuck the war' at St Petersburg concert". Business Insider. 23 May 2022. Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Karev, Andrey (10 July 2022). "'I'll be exonerated much sooner than this'". Novaya Gazeta Europa. Archived from the original on 12 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ "Russia-Ukraine war: Moscow politician gets 7 years for denouncing war". BBC News. 8 July 2022. Archived from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ "Russia: 20,000 activists subject to heavy reprisals as Russia continues to crack down on anti-war movement at home". Amnesty International. 20 July 2023.

- ^ "Returning Russians who backed Ukraine must be sent to the mines, says Putin ally". ABC News. 11 October 2023.

- ^ "Russian State Duma speaker says 'traitors' who left after Ukraine invasion not welcome in Russia". Meduza. 25 November 2023.

- ^ "Коктейли Молотова и рельсовая война — стратегия новой российской оппозиции. Роман Попков поговорил с "партизанами" об их методах борьбы" [Molotov cocktails and rail war: the strategy of the new Russian opposition. Roman Popkov speaks with the "partisans" about their methods of struggle]. БелСат (in Russian). 12 August 2022.

- ^ Smart, Jason Jay (23 August 2022). "Exclusive interview: Russia's NRA Begins Activism". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 9 July 2023. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ "Российская оппозиция начинает вооруженное сопротивление Путину: подписано декларацию". Главком | Glavcom (in Russian). 31 August 2022. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ Pikulicka-Wilczewska, Agnieszka; Pikulicka-Wilczewska, Agnieszka (11 May 2023). "How Russians end up in a far-right militia fighting in Ukraine". Reuters.

- ^

- Osborn, Andrew; Liffey, Kevin (23 June 2023). "Russia accuses mercenary boss of mutiny after he says Moscow killed 2,000 of his men". Reuters. Archived from the original on 23 June 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- Cooney, Christy; Seales, Rebecca (23 June 2023). "Russia accuses Wagner chief of urging 'armed mutiny'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 23 June 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- Dress, Brad (23 June 2023). "Wagner chief says Russia's war in Ukraine intended to benefit elites, accuses Moscow of lying". The Hill. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- "'All the way': Wagner head escalates threats with Russia military". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- Sauer, Pjotr (23 June 2023). "Wagner chief accuses Moscow of lying to public about Ukraine". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 23 June 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- Sauer, Pjotr (23 June 2023). "Russia investigates Wagner chief for 'armed mutiny' after call for attack on military". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 24 June 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- Williams, Tom; Nancarrow, Dan (24 June 2023). "Live: Wagner fighters allegedly march into Russia, with leader vowing to go 'all the way' against military". ABC News. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- Gavin, Gabriel; Ross, Tim; Sheftalovich, Zoya (23 June 2023). "Putin in crisis: Wagner chief Prigozhin declares war on Russian military leadership, says 'we will destroy everything'". POLITICO. Archived from the original on 23 June 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ Walker, Shaun (27 June 2023). "Putin's portrayal of response to uprising as a Kremlin win is proving a hard sell". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 28 June 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ Aron, Leon (25 June 2023). "'The People Are Silent': The Main Reason the Wagner Mutiny Bodes Ill for Putin". Politico. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023.

- ^ "Russians Greeted Wagner Mutiny With a Shrug and Internet Jokes". Bloomberg News. 28 June 2023. Archived from the original on 28 June 2023.

- ^ Stewart, Briar (27 June 2023). "Why average Russians did not rush to streets to defend Putin. But some rallied for Wagner troops". CBC. Archived from the original on 27 June 2023.

- ^ a b c "Putin backs proposal allowing him to remain in power in Russia beyond 2024". The Guardian. 10 March 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ a b "Putin backs amendment allowing him to remain in power". NBC News. 10 March 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ "The Rocky Road to Replacing Vladimir Putin". Chatham House. 16 April 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ "Putin's 2024 Problem: Election Win Raises Curtain On Clouded Future". RFE/RL. 18 March 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ a b "Putin wins referendum on constitutional reforms". DW News. 7 February 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Russia bans anti-war candidate from challenging Putin". BBC News. 23 December 2023. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ Latypova, Leyla (22 November 2023). "Meet Putin's Possible Election Opponent: A Single Mother of 3 Calling for Peace". The Moscow Times.

- ^ "Pro-Peace Putin Challenger Blocked From Ballot". themoscowtimes.com. The Moscow Times. 23 December 2023.

- ^ "Putin critic Girkin wants to stand in Russia presidential election". BBC News. 19 November 2023. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ "Russia jails nationalist critic Igor Girkin for four years over 'extremism'". AlJazeera. 25 January 2024. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ a b "Kremlin propagandists finally acknowledge anti-war presidential hopeful Boris Nadezhdin, and — surprise! — they say Kyiv and Russia's exiled opposition are controlling him". Meduza. 2 February 2024.

- ^ "Meet Boris Nadezhdin, Vladimir Putin's brave challenger". The Economist. 1 February 2024. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "Putin challenger Boris Nadezhdin barred from Russia's election". BBC News. 8 February 2024. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ "The anti-war candidate channelling Russians' discontent with Putin". www.ft.com. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ "Russians queue to register election candidate opposed to Ukraine offensive". France 24. 23 January 2024. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ a b "Russia blocks Boris Nadezhdin from presidential election: DW News". DW News. 8 February 2024. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ a b "Who is Boris Nadezhdin, Putin challenger who hopes to run in Russia presidential election". Channel 4 News. 8 December 2024. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ a b c Talmazan, Yuliya (8 February 2024). "Russia bars anti-war Putin critic Boris Nadezhdin from next month's election". NBC News. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ "Yekaterina Duntsova barred from running against Putin in election". Reuters. 23 December 2023. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ "Russia bars ex-journalist Duntsova from running in presidential election". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ "Оппозиционные политики призвали поддержать выдвижение Надеждина". Радио Свобода (in Russian). 22 January 2024. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ "Юрий Шевчук записал видео в поддержку Бориса Надеждина". Радио «Свобода» (in Russian). Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ "«Безопасное политическое действие». Почему выстроились очереди подписывающихся за участие Бориса Надеждина в выборах президента России". BBC News Русская служба (in Russian). 22 January 2024. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ "Юлия Навальная поставила подпись за выдвижение Бориса Надеждина в президенты России". Meduza (in Russian). Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ "'Hope for Change' or 'Kremlin Spoiler': Who Is Boris Nadezhdin, the Presidential Hopeful Uniting Pro-Peace Russians?". The Moscow Times. 25 January 2024.

- ^ "Russian Anti-War Candidacy Bid An Unexpected Obstacle In Kremlin's Effort To Smoothly Reinstall Putin". RFE/RL. 30 January 2024. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ "Putin's antiwar rival blocked from contesting Russia presidential election". AlJazeera. 8 February 2024. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ "Russian anti-war candidate Boris Nadezhdin banned from election". The Guardian. 8 February 2024.

- ^ "Russia blocks war critic Nadezhdin from facing Putin in presidential vote". France24. 8 February 2024. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ "Navalny Calls for Election Day Protest Against Putin, Ukraine Invasion". The Moscow Times. 1 February 2024.

- ^ "'They killed him': Was Putin's critic Navalny murdered?". AlJazeera. 17 February 2024. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ "Navalny tributes removed by group of masked men as Moscow police look on". The Independent. 17 February 2024.

- ^ "Moscow police begin arresting people leaving flowers in memorial of Alexey Navalny". Meduza. 17 February 2024.

- ^ "Russia's most famous opposition figure has died in prison". Meduza. 16 February 2024. Archived from the original on 16 February 2024. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ "Ukraine war: Troops could quit Severodonetsk amid Russian advance - official". BBC News. 27 May 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ "Making Putin Great (Again and Again) – Zhanna Agalakova". Moscow Times. 15 December 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ "Russian Actress, Kremlin Critic Akhedzhakova Leaves Moscow Theater Amid Pressure". RFE/RL. 30 March 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Moscow Theater Cancels Plays With Kremlin Critic Liya Akhedzhakova". Moscow Times. 9 February 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Abdulmalik Akhmedilov". Committee to Protect Journalists. 11 August 2009. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Russia: Two years after Aleksei Navalny's arrest, Russian opposition figures suppressed, jailed or exiled". Amnesty International. 23 January 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "'Wise and humane': Soviet dissident Lyudmila Alexeyeva dies aged 91". The Guardian. 9 December 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Pussy Riot's Maria Alyokhina says she escaped Russia dressed as a food courier". CNN. 12 May 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "'We are Russians just like you': anti-Putin militias enter the spotlight". The Guardian. 24 May 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Russian opposition activist Vladimir Ashurkov is granted asylum in UK". The Guardian. 1 April 2015. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ a b c "In Moscow, Putin's opponents chalk up a symbolic victory". Politico. 15 September 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Russian opposition election candidate shot". Reuters. 21 November 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Here are 10 critics of Vladimir Putin who died violently or in suspicious ways". Washington Post. 23 April 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Russian Khimki forest journalist Mikhail Beketov dies". BBC News. 9 April 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ "Russian opposition leader found guilty of embezzlement; his lawyers pledge to appeal". Los Angeles Town. 8 February 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Boris Berezovsky: Russia remembers 'controversial figure'". BBC News. 24 March 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Congratulations, You're an Elected Russian Opposition Official! Now What?". Moscow Times. 3 February 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Will a New Generation of Russians Modernize Their Country?". Carengie. 4 February 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Another Putin critic reportedly targeted in Kremlin 2019 poisoning operation". The Independent. 9 June 2019. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "The National Bolshevik was buried under guard". Kommersant. 14 December 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Anti-Putin activist found dead in Moscow home". The Guardian. 6 November 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "The brave journalists risking all to hold Vladimir Putin to account". The New European. 17 February 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "Russian regulator warns local media over coverage of Ukraine war". AlJazeera. 26 February 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Russia bans anti-war candidate from challenging Putin". BBC News. 23 December 2023. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ "Daughter of ex-Russian PM, defying Kremlin, eyes top post in key Ukraine region". Reuters. 20 July 2015. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Former Russian PM Gaidar poisoned, say his doctors". The Independent. 1 December 2006. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Russian star and Putin critic Maxim Galkin packs out Irish venue for live show tonight". Independent.ie. 26 August 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Putin critic Girkin wants to stand in Russia presidential election". BBC News. 19 November 2023. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ "Russia arrests pro-war Putin critic Igor Girkin, according to reports". The Guardian. 21 July 2023. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ "Igor Girkin shot down a passenger jet, then insulted Putin. Which one put him in jail?". BBC News. 19 November 2023. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ "Nikolai Glushkov: Putin critic 'strangled in London home by third party'". BBC News. 9 April 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Russia-Ukraine war: Moscow politician gets 7 years for denouncing war". BBC News. 8 July 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ "Russian Duma expels anti-Putin MP Gennady Gudkov". BBC News. 14 September 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "Agent of chaos: How to read Putin's lies, U-turns and retreats". Politico. 12 November 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ a b c "Vladimir Putin's critics: dead, jailed, exiled". France24. 17 April 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Nadya Karpova: The Russia striker speaking out against war in Ukraine". BBC Sport. 6 June 2022. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "Garry Kasparov: 'Why become a martyr? I can do much more outside Russia'". The Guardian. 30 April 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "Russia is electing a new parliament--but hardly anyone thinks Putin's party will lose". Los Angeles Times. 17 September 2016. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "Liberal anti-Putin coalition causes upset in Moscow council elections". The Guardian. 11 September 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "Russia's other presidential hopefuls". BBC News. 6 March 2004. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ "Mikhail Khodorkovsky reunion: son Pavel speaks after decade of separation". The Telegraph. 21 December 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "How Sergey Lavrov lost his levity to become Putin's Mr Nyet". The Times. 6 March 2022. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "Mariupol defenders ignore Russia surrender deadline:Putin could use nuclear weapons: Khrushchev's great-granddaughter". BBC News. 17 April 2022. p. 2. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

Ms Khrushcheva - a Russia scholar at the New School in New York and long-time critic of Mr Putin

- ^ "Russian journalist's body found after disappearance". The Guardian. 5 August 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ "Alexander Litvinenko's widow joins anti-Putin protest outside Russian embassy". The Guardian. 25 February 2023. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ "Russian Police Raid Opposition Politicians' Homes, Detain Activist". Moscow Times. 18 May 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Russian oil boss Ravil Maganov who criticised war in Ukraine dies 'after falling from hospital window'". Sky News. 1 September 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ "Russia's anti-war lobby goes online". France24. 26 February 2022. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "The participant of the rally in Samara demanded the resignation of the chairman of the CEC". Teppa.ru. 27 December 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "CVC Central Election Committee on the elections to the Coordinating Council of the Russian Opposition". Archived from the original on 23 September 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ^ Navalny, Alexei (4 October 2012). "Ещё не поздно поддержать Матвеева (и остальных) и помочь им пройти во второй тур. Голосование идёт". Twitter. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "The Russian billionaire daring to speak out about Putin". BBC News. 11 August 2022. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "Two prominent activists are planning to run for the same Moscow City Duma seat, prompting tensions among opposition supporters". Meduza. 13 May 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ Freedom House (2014). Freedom in the World 2014: The Annual Survey of Political Rights and Civil Liberties. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 573. ISBN 9781442247079.

- ^ "Dmitry Muratov: Nobel Peace Prize winner and Putin critic 'doused in paint during attack on Moscow train'". The Independent. 8 April 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Ukrainian counter-offensive against Russia expected in 'weeks rather than months', Western officials say". i. 1 June 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "'I am not afraid': Yulia Navalnaya, 'first lady' of the Russian opposition movement, emerges as a force to be reckoned with". MSNBC. 11 February 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Factbox: Who is Alexei Navalny and what does he say of Russia, Putin and death?". Reuters. 13 April 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "The man who dared to criticize Putin". DW. 27 February 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "'My father was killed because he understood early the plans of Putin': Zhanna Nemtsova". CNN. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ "'Crime of the regime': Russian dissident Orlov reacts to Navalny's death". France24. 16 February 2024. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ "Ukraine war: Oleg Orlov faces jail time for criticising Putin's war". BBC News. 9 June 2023. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ "Former Russian state TV journalist claims Putin 'doesn't have enough Novichok' to kill growing number of critics". Sky News. 11 May 2023. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ "Marina Ovsyannikova: Anti-war Russian journalist sentenced in absentia". BBC News. 4 October 2023. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ Nechepurenko, Ivan; Bilefsky, Dan (24 February 2022). "Thousands of Russians protest President Vladimir V. Putin's assault on Ukraine. Some chant: 'No to war!'". New York Times. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "Russian Rapper Oxxxymiron Stages Anti-War Rallying Cry From Istanbul". Moscow Times. 19 April 2022. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "Anti-war Russians in Turkey unite at rap concert for Ukraine". Reuters. 15 March 2022. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "Hunger Striker Oleg Shein Becomes Russia's Opposition Hero". Bloomberg News. 18 February 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ "In Memory of Dmitry Petrov". CrimethInc. 3 May 2023. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ "Russia: Prisoner of conscience Nikolai Platoshkin's suspended conviction must be quashed". Amnesty International. 19 May 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "Targeted killings spark debate within Russian opposition". Politico. 24 April 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Russian activist Lev Ponomarev: 'The Kremlin is digging its own grave by letting spooks take over domestic policy'". The Independent. 20 January 2019. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "'Weak' Putin killed Wagner mercenary chief Prigozhin, Zelensky says". The Independent. 8 September 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ "Kremlin critic Mikhail Prokhorov 'does not fear being sent to jail'". The Telegraph. 18 September 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Vladimir Putin's time as leader has passed, says Mikhail Prokhorov". The Telegraph. 1 February 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "'Kremlin framed me' says Russia's anti-Putin Communist star caught with elk blood on his hands". The Telegraph. 29 October 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ "Veteran Communist Party Lawmaker Detained for Illegal Hunting". Moscow Times. 29 October 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ "Russian Politician Missing for 3 Days". Los Angeles Times. 9 February 2004. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Russia election: Vladimir Putin celebrates victory". BBC News. 6 March 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Mikhail Gorbachev had a 'huge impact on world history', says Vladimir Putin". The Independent. 31 August 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Russians who live abroad say Moscow is hardening the views of those back home". NBC. 27 March 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Russian Writer, Staunch Kremlin Critic Barred From Entering Georgia". RFE/RL. 2 June 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Russia prosecutes veteran rock star for criticising Ukraine conflict". France24. 20 May 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Opposition Politician Accused of 'Discrediting' Russian Military". Moscow Times. 15 April 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Putin Critic Serving Life Sentence Dies In Jail". RFE/RL. 15 December 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Meet Natalya Sindeyeva – has she got news for Vladimir Putin". The Guardian. 20 February 2022. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "Russian artist jailed for seven years over Ukraine war price tag protest". The Guardian. 16 November 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ "Russian regional deputies urge Putin to issue decree ending mobilisation". Reuters. 6 December 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Russia 'drove democracy activist to fireball suicide'". The Times. 11 October 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Russian, Ukrainian ballet stars to dance together in Naples". The Independent. 4 April 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Russian soccer player Fedor Smolov publicly opposes Putin's decision to invade Ukraine: 'No to war'". Washington Post. 29 September 2023. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Russian opposition figures: Ksenia Sobchak". BBC News. 12 June 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "Ksenia Sobchak: Police raid home of 'Russian Paris Hilton' and Putin critic". Sky News. 26 October 2022. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "Russia: The KGB's Post-Soviet 'Commercialization'". RFE/RL. 20 December 2006. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Russian opposition figures: Sergei and Anastasia Udaltsov". BBC News. 12 June 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Russian Mayor, an Opposition Figure, Is Arrested". New York Times. 3 July 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Top radio chief sees Russia 'thrown back 40 years'". France24. 26 April 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ "'Highly probable' Pussy Riot activist was poisoned, say German doctors". The Guardian. 18 September 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Russians tire of Putin, says opposition leader". Reuters. 30 November 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Owner of Russian opposition website killed". Reuters. 31 August 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "From Russia with $3 billion. Another Putin opponent may have fled to London". The Guardian. 30 August 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Red Z = Wagner". Twitter. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

External links

Media related to Demonstrations and protests in Russia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Demonstrations and protests in Russia at Wikimedia Commons- List of political prisoners in Russia (Russian) in 2015, compiled by "New Chronicle of Current Events".