Empedocles: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 1182025028 by 208.52.61.125 (talk) Both spellings are used, but "Acragas" is a disambiguation link. |

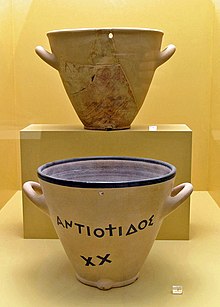

m Added a picture |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|5th century BC Greek philosopher}} |

{{Short description|5th century BC Greek philosopher}} |

||

{{Other uses}} |

{{Other uses}} |

||

[[File:Empedokles.jpeg|thumb|Empedocles]] |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=April 2020}} |

{{Use dmy dates|date=April 2020}} |

||

{{Infobox philosopher |

{{Infobox philosopher |

||

Revision as of 22:29, 15 November 2023

Empedocles | |

|---|---|

Empedocles, 17th-century engraving | |

| Born | c. 494 BC |

| Died | c. 434 BC |

| Era | Pre-Socratic philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

Main interests | Cosmogony, Biology |

Notable ideas | Classical four elements: fire, air, earth and water Love and Strife as opposing physical forces |

Empedocles (/ɛmˈpɛdəkliːz/; Template:Lang-grc-gre; c. 494 – c. 434 BC, fl. 444–443 BC) was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for originating the cosmogonic theory of the four classical elements. He also proposed forces he called Love and Strife which would mix and separate the elements, respectively.

Empedocles challenged the practice of animal sacrifice and killing animals for food. He developed a distinctive doctrine of reincarnation. He is generally considered the last Greek philosopher to have recorded his ideas in verse. Some of his work survives, more than is the case for any other pre-Socratic philosopher. Empedocles' death was mythologized by ancient writers, and has been the subject of a number of literary treatments.

Life

Although the exact dates of Empedocles' birth and death are unknown and ancient accounts of his life conflict on the exact details, they agree that he was born in the early 5th century BC in the Greek city of Akragas in Magna Graecia, present-day Sicily.[1] Modern scholars believe the accuracy of the accounts that he came from a rich and noble family and that his grandfather, also named Empedocles, had won a victory in the horse race at Olympia in the 71st. Olympiad (496–495 BC),[a] Little else can be determined with accuracy.[1]

Primary sources of information on the life of Empedocles come from the Hellenistic period, several centuries after his own death and long after any reliable evidence about his life would have perished.[2] Modern scholarship generally believes that these biographical details, including Aristotle's assertion that he was the "father of rhetoric",[b] his chronologically impossible tutelage under Pythagoras, and his employment as a doctor and miracle worker, were fabricated from interpretations of Empedocles' poetry, as was common practice for the biographies written during this time.[2]

Death and legacy

According to Aristotle, he died at the age of 60 (c. 430 BC), even though other writers have him living up to the age of 109.[c] Likewise, there are myths concerning his death: a tradition, which is traced to Heraclides Ponticus, represented him as having been removed from the Earth; whereas others had him perishing in the flames of Mount Etna.[d] Diogenes Laërtius records the legend that Empedocles died by throwing himself into Mount Etna in Sicily, so that the people would believe his body had vanished and he had turned into an immortal god;[e] the volcano, however, threw back one of his bronze sandals, revealing the deceit. Another legend maintains that he threw himself into the volcano to prove to his disciples that he was immortal; he believed he would come back as a god after being consumed by the fire. Lucretius speaks of him with enthusiasm, and evidently viewed him as his model.[f] Horace also refers to the death of Empedocles in his work Ars Poetica and admits poets the right to destroy themselves.[g] In Icaro-Menippus, a comedic dialogue written by the second-century satirist Lucian of Samosata, Empedocles' final fate is re-evaluated. Rather than being incinerated in the fires of Mount Etna, he was carried up into the heavens by a volcanic eruption. Although a bit singed by the ordeal, Empedocles survives and continues his life on the Moon, surviving by feeding on dew.

Burnet states that Empedocles likely did not die in Sicily, that both the positive story of Empedocles being taken up to heaven and the negative one about him throwing himself into a volcano could be easily accepted by ancient writers, as there was no local tradition to contradict them.[4]

Empedocles' death is the subject of Friedrich Hölderlin's play Tod des Empedokles (The Death of Empedocles) as well as Matthew Arnold's poem Empedocles on Etna.

Philosophy

Based on the surviving fragments of his work, modern scholars generally believe that Empedocles was directly responding to Parmenides' doctrine of monism and was likely acquainted with the work of Anaxagoras, although it is unlikely he was aware of either the later Eleatics or the doctrines of the Atomists.[5] Many later accounts of his life claim that Empedocles studied with the Pythagoreans on the basis of his doctrine of reincarnation, although he may have instead learned this from a local tradition rather than directly from the Pythagoreans.[5]

Cosmogony

Empedocles established four ultimate elements which make all the structures in the world—fire, air, water, earth.[6][h] Empedocles called these four elements "roots", which he also identified with the mythical names of Zeus, Hera, Nestis, and Aidoneus[i] (e.g., "Now hear the fourfold roots of everything: enlivening Hera, Hades, shining Zeus. And Nestis, moistening mortal springs with tears").[7] Empedocles never used the term "element" (στοιχεῖον, stoicheion), which seems to have been first used by Plato.[j][better source needed] According to the different proportions in which these four indestructible and unchangeable elements are combined with each other the difference of the structure is produced.[6] It is in the aggregation and segregation of elements thus arising, that Empedocles, like the atomists, found the real process which corresponds to what is popularly termed growth, increase or decrease. One interpreter describes his philosophy as asserting that "Nothing new comes or can come into being; the only change that can occur is a change in the juxtaposition of element with element."[6] This theory of the four elements became the standard dogma for the next two thousand years.

The four elements, however, are simple, eternal, and unalterable, and as change is the consequence of their mixture and separation, it was also necessary to suppose the existence of moving powers that bring about mixture and separation. The four elements are both eternally brought into union and parted from one another by two divine powers, Love and Strife (Philotes and Neikos).[6] Love (φιλότης) is responsible for the attraction of different forms of what we now call matter, and Strife (νεῖκος) is the cause of their separation.[k] If the four elements make up the universe, then Love and Strife explain their variation and harmony. Love and Strife are attractive and repulsive forces, respectively, which are plainly observable in human behavior, but also pervade the universe. The two forces wax and wane in their dominance, but neither force ever wholly escapes the imposition of the other.

As the best and original state, there was a time when the pure elements and the two powers co-existed in a condition of rest and inertness in the form of a sphere.[6] The elements existed together in their purity, without mixture and separation, and the uniting power of Love predominated in the sphere: the separating power of Strife guarded the extreme edges of the sphere.[l] Since that time, strife gained more sway[6] and the bond which kept the pure elementary substances together in the sphere was dissolved. The elements became the world of phenomena we see today, full of contrasts and oppositions, operated on by both Love and Strife.[6] Empedocles assumed a cyclical universe whereby the elements return and prepare the formation of the sphere for the next period of the universe.

Empedocles attempted to explain the separation of elements, the formation of earth and sea, of Sun and Moon, of atmosphere.[6] He also dealt with the first origin of plants and animals, and with the physiology of humans.[6] As the elements entered into combinations, there appeared strange results—heads without necks, arms without shoulders.[6][m] Then as these fragmentary structures met, there were seen horned heads on human bodies, bodies of oxen with human heads, and figures of double sex.[6][n] But most of these products of natural forces disappeared as suddenly as they arose; only in those rare cases where the parts were found to be adapted to each other did the complex structures last.[6] Thus the organic universe sprang from spontaneous aggregations that suited each other as if this had been intended.[6] Soon various influences reduced creatures of double sex to a male and a female, and the world was replenished with organic life.[6]

Psychology

Like Pythagoras, Empedocles believed in the transmigration of the soul or metempsychosis, that souls can be reincarnated between humans, animals and even plants.[o] According to him, all humans, or maybe only a selected few among them,[8] were originally long-lived daimons who dwelt in a state of bliss until committing an unspecified crime, possibly bloodshed or perjury.[8][9] As a consequence, they fell to Earth, where they would forced to spend 30,000 cycles of metempsychosis through different bodies before being able to return to the sphere of divinity.[8][9] One's behavior during his lifetime would also determine his next incarnation.[8] Wise people, who have learned the secret of life, are closer to the divine,[6][p] while their souls similarly closer are to the freedom from the cycle of reincarnations, after which they are able to rest in happiness for eternity.[q] This cycle of mortal incarnation seems to have been inspired by the god Apollo's punishment as a servant to Admetus.[9]

Empedocles was a vegetarian[r][better source needed] and advocated vegetarianism, since the bodies of animals are also dwelling places of punished souls.[s] For Empedocles, all living things were on the same spiritual plane; plants and animals are links in a chain where humans are a link too.[6]

Empedocles is credited with the first comprehensive theory of light and vision. Historian Will Durant noted that "Empedocles suggested that light takes time to pass from one point to another."[10][better source needed] He put forward the idea that we see objects because light streams out of our eyes and touches them. While flawed, this became the fundamental basis on which later Greek philosophers and mathematicians like Euclid would construct some of the most important theories of light, vision, and optics.[11][better source needed]

Knowledge is explained by the principle that elements in the things outside us are perceived by the corresponding elements in ourselves.[t] Like is known by like. The whole body is full of pores and hence respiration takes place over the whole frame. In the organs of sense these pores are specially adapted to receive the effluences which are continually rising from bodies around us; thus perception occurs.[u] In vision, certain particles go forth from the eye to meet similar particles given forth from the object, and the resultant contact constitutes vision.[v] Perception is not merely a passive reflection of external objects.[12][better source needed]

Empedocles also attempted to explain the phenomenon of respiration by means of an elaborate analogy with the clepsydra, an ancient device for conveying liquids from one vessel to another.[w][13] This fragment has sometimes been connected to a passage[x] in Aristotle's Physics where Aristotle refers to people who twisted wineskins and captured air in clepsydras to demonstrate that void does not exist. The fragment certainly implies that Empedocles knew about the corporeality of air, but he says nothing whatever about the void, and there is no evidence that Empedocles performed any experiment with clepsydras.[13]

Writings

According to Diogenes Laertius,[y] Empedocles wrote two poems, one "On Nature" and the other "On Purifications" which together comprised 5000 lines. However, only approximately 550 lines of his poetry survive, quoted in fragments by later ancient sources.

In the old editions of Empedocles, about 450 lines were ascribed to "On Nature" which outlined his philosophical system, and explains not only the nature and history of the universe, including his theory of the four classical elements, but also theories on causation, perception, and thought, as well as explanations of terrestrial phenomena and biological processes. The other 100 lines were typically ascribed to his "Purifications", which was taken to be a poem about ritual purification, or the poem that contained all his religious and ethical thought, which early editors supposed that it was a poem that offered a mythical account of the world which may, nevertheless, have been part of Empedocles' philosophical system.

However, with the discovery of the Strasbourg papyrus,[14][z] which contains a large section of "On Nature" that includes many lines that were formerly attributed to "On Purifications"[15] there is now considerable debate[16][17] about whether the surviving fragments of his teaching should be attributed to two separate poems, with different subject matter, or whether they may all derive from one poem with two titles,[18] or whether one title refers to part of the whole poem.

Notes

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 51

- ^ Aristotle, Poetics, 1, ap. Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 57.

- ^ Apollonius, ap. Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 52, comp. 74, 73

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 67, 69, 70, 71; Horace, ad Pison. 464, etc.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 69

- ^ See especially Lucretius, i. 716, etc.[3]

- ^ Horace Ars Poetica

- ^ Frag. B17 (Simplicius, Physics, 157–159)

- ^ Frag. B6 (Sextus Empiricus, Against the Mathematicians, x, 315)

- ^ Plato, Timaeus, 48b–c

- ^ Frag. B35, B26 (Simplicius, Physics, 31–34)

- ^ Frag. B35 (Simplicius, Physics, 31–34; On the Heavens, 528–530)

- ^ Frag. B57 (Simplicius, On the Heavens, 586)

- ^ Frag. B61 (Aelian, On Animals, xvi 29)

- ^ Frag. B127 (Aelian, On Animals, xii. 7); Frag. B117 (Hippolytus, i. 3.2)

- ^ Clement of Alexandria, Miscellanies, iv. 23.150

- ^ Clement of Alexandria, Miscellanies, v. 14.122

- ^ Plato, Meno

- ^ Sextus Empiricus, Against the Mathematicians, ix. 127; Hippolytus, vii. 21

- ^ Frag. B109 (Aristotle, On the Soul, 404b11–15)

- ^ Frag. B100 (Aristotle, On Respiration, 473b1–474a6)

- ^ Frag. B84 (Aristotle, On the Senses and their Objects, 437b23–438a5)

- ^ Aristotle, On Respiration 13

- ^ Aristotle, Physics, 213a24–7

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 77

- ^ Not to be confused with The Strasbourg papyrus

References

- ^ a b Kingsley & Parry 2020, §1.

- ^ a b Inwood 2001, pp. 6–8.

- ^ Sedley 2003.

- ^ Burnet 1892, pp. 202–203.

- ^ a b Inwood 2001, p. 6-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Wallace 1911.

- ^ Kingsley 1995.

- ^ a b c d Inwood 2001, pp. 55–68.

- ^ a b c Primavesi 2008, pp. 261–268.

- ^ Durant, Will. The Story of Civilization, Volume 2: The Life of Greece (New York; Simon & Schuster) 1939, p. 339.

- ^ Let There be Light 7 August 2006 01:50 BBC Four

- ^ "Empedocles – Encyclopedia".

- ^ a b Barnes 2002, p. 313.

- ^ a b Martin & Primavesi 1999.

- ^ Kingsley & Parry 2020.

- ^ Inwood 2001, pp. 8–21.

- ^ Trépanier 2004.

- ^ Osborne 1987, pp. 24–31, 108.

Bibliography

Ancient Testimony

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:8. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:8. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

References

- Barnes, Jonathan (11 September 2002). The Presocratic Philosophers. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-96512-0.

- Burnet, John (1892). Early Greek Philosophy. Adam and Charles Black.

- Inwood, Brad (2001). The Poem of Empedocles: A Text and Translation with an Introduction (Revised ed.). University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-8353-1.

- Guthrie, W. K. C. (1962). A History of Greek Philosophy: Volume 2, The Presocratic Tradition from Parmenides to Democritus. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29421-8.

- Kingsley, K. Scarlett; Parry, Richard (2020). "Empedocles". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Kingsley, Peter (1995). Ancient Philosophy, Mystery, and Magic: Empedocles and Pythagorean Tradition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-814988-3.

- Martin, Alain; Primavesi, Oliver (1999). L'Empédocle de Strasbourg: (P. Strasb. gr. Inv. 1665-1666) (in French). Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-015129-9.

- Primavesi, Oliver (27 October 2008). "Empedocles: Physical and Mythical Divinity". In Curd, Patricia; Graham, Daniel W. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Presocratic Philosophy. Oxford University Press, US. ISBN 978-0-19-514687-5.

- Osborne, Catherine (1987). Rethinking early Greek philosophy : Hippolytus of Rome and the Presocratics. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0-7156-1975-6.

- Sedley, D. N. (2003). Lucretius and the Transformation of Greek Wisdom. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54214-2.

- Trépanier, Simon (2004). Empedocles: An Interpretation. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-96700-6.

- Wallace, William (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). pp. 344–345.

- Wright, M. R. (1995). Empedocles: The Extant Fragments (new ed.). London: Bristol Classical Press. ISBN 1-85399-482-0.

Further reading

- Chitwood, Ava (2004). Death by philosophy : the biographical tradition in the life and death of the archaic philosophers Empedocles, Heraclitus, and Democritus. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472113880.

- Campbell, Gordon. "Empedocles". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Freeman, Kathleen (1948). Ancilla to the Pre-Socratic Philosophers: A Complete Translation of the Fragments in Diels Fragmente Der Vorsokratiker. Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-1-60680-256-4.

- Gottlieb, Anthony (2000). The Dream of Reason: A History of Western Philosophy from the Greeks to the Renaissance. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 0-7139-9143-7.

- Kirk, G. S.; Raven, J.E.; Schofield, M. (1983). The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-25444-2.

- Lambridis, Helle (1976). Empedocles : a philosophical investigation. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-6615-6.

- Long, A. A. (1999). The Cambridge Companion to Early Greek Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44122-6.

- Saetta Cottone, Rossella (2023). Soleil et connaissance. Empédocle avant Platon. Paris: Les Belles Lettres. ISBN 9782350882031.

- Stamatellos, Giannis (2007). Plotinus and the Presocratics: A Philosophical Study of Presocratic Influences in Plotinus’ Enneads. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Stamatellos, Giannis (2012). Introduction to Presocratics: A Thematic Approach to Early Greek Philosophy with Key Readings. Wiley-Blackwell.

External links

- Empedokles: Fragments, translated by Arthur Fairbanks, 1898.

- Empedocles Archived 9 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine by Jean-Claude Picot with an extended and updated bibliography

- Empedocles: Fragments at demonax.info

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Empedocles", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Works by or about Empedocles at the Internet Archive

- Works by Empedocles at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Deaths from fire

- 5th-century BC Greek philosophers

- 5th-century BC poets

- Ancient Acragantines

- Ancient Greek shamans

- Pluralist philosophers

- Ancient Greek physicists

- Philosophers of Magna Graecia

- Natural philosophers

- Philosophers of science

- Presocratic philosophers

- Philosophers of love

- Sicilian Greeks

- 490s BC births

- 430s BC deaths