Gadsden flag: Difference between revisions

→Appearance and symbolism: this is more professional word. Motto is a common speaking word Tags: Reverted Mobile edit Mobile app edit Android app edit |

m →Appearance and symbolism: Fixed typo Tags: Manual revert canned edit summary Mobile edit Mobile app edit Android app edit |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

==Appearance and symbolism== |

==Appearance and symbolism== |

||

===Variations in appearance=== |

===Variations in appearance=== |

||

Many variations of the Gadsden flag exist. The motto sometimes includes an apostrophe in the word "Don't" and sometimes not;<ref name="natgeo" />{{rp|339}} the [[typeface]] used for the |

Many variations of the Gadsden flag exist. The motto sometimes includes an apostrophe in the word "Don't" and sometimes not;<ref name="natgeo" />{{rp|339}} the [[typeface]] used for the motto is sometimes a [[serif]] typeface and other times sans-serif. The rattlesnake sometimes is shown as resting on a green ground; representations dating from 1885 and 1917 do not display anything below the rattlesnake. The rattlesnake usually faces to the left, and the early representations mentioned above face left. However, some versions of the flag show the snake facing to the right. |

||

===History of the rattlesnake symbol in America=== |

===History of the rattlesnake symbol in America=== |

||

Revision as of 03:14, 30 August 2023

| |

| Use | Banner |

|---|---|

| Proportion | Varies, generally 2:3 |

| Adopted | December 20, 1775 |

| Design | A yellow banner charged with a yellow coiled timber rattlesnake facing toward the hoist sitting upon a patch of green grass, with thirteen rattles for the thirteen colonies, the words "DONT TREAD ON ME" positioned below the snake in black |

| Designed by | Christopher Gadsden |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Libertarianism in the United States |

|---|

|

The Gadsden flag is a historical American flag with a yellow field depicting a timber rattlesnake[1][2] coiled and ready to strike. Beneath the rattlesnake are the words "DONT TREAD ON ME".[a] Some modern versions of the flag include an apostrophe.

The flag is named for Christopher Gadsden, a South Carolina delegate to the Continental Congress and brigadier general in the Continental Army[4][5] who designed the flag in 1775 during the American Revolution.[6] He gave the flag to Commodore Esek Hopkins, and it was unfurled on the main mast of Hopkins' flagship USS Alfred on December 20, 1775.[5][7] Two days later, Congress made Hopkins commander-in-chief of the Continental Navy.[8] He adopted the Gadsden banner as his personal flag, flying it from the mainmast of the flagship while he was aboard.[5] The Continental Marines also flew the flag during the early part of the war.[6]

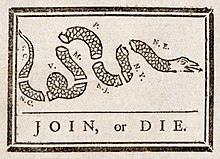

The rattlesnake was a symbol of the unity of the Thirteen Colonies at the start of the Revolutionary War, and it had a long history as a political symbol in America. Benjamin Franklin used it for his Join, or Die woodcut in 1754.[5][9] Gadsden intended his flag as a warning to Britain not to violate the liberties of its American subjects.[5]

The flag has been described as the "most popular symbol of the American revolution."[5] Its design proclaims an assertive warning of vigilance and willingness to act in defense against coercion.[10] This has led it to be associated with the ideas of individualism and liberty.[11][12][13][14][15][16] It is often used in the United States as a symbol for right-libertarianism, classical liberalism, and small government; for distrust or defiance against authorities and government.[17][18][19]

Appearance and symbolism

Variations in appearance

Many variations of the Gadsden flag exist. The motto sometimes includes an apostrophe in the word "Don't" and sometimes not;[20]: 339 the typeface used for the motto is sometimes a serif typeface and other times sans-serif. The rattlesnake sometimes is shown as resting on a green ground; representations dating from 1885 and 1917 do not display anything below the rattlesnake. The rattlesnake usually faces to the left, and the early representations mentioned above face left. However, some versions of the flag show the snake facing to the right.

History of the rattlesnake symbol in America

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2022) |

The timber rattlesnake can be found in the area of the original Thirteen Colonies. Like the bald eagle, part of its significance is that it was unique to the Americas, serving as a means of showing a separate identity from the Old World. Its use as a symbol of the American colonies can be traced back to the publications of Benjamin Franklin. In 1751, he made the first reference to the rattlesnake in a satirical commentary published in his Pennsylvania Gazette. It had been the policy of Parliament to send convicted criminals to the Americas (primarily the Province of Georgia), so Franklin suggested that they thank them by sending rattlesnakes to Britain.[21]

In 1754, during the French and Indian War, Franklin published Join, or Die, a woodcut of a snake cut into eight sections. It represented the colonies, with New England joined as the head and South Carolina as the tail, following their order along the coast. This was the first political cartoon published in an American newspaper.[citation needed]

In 1774, Paul Revere added Franklin's iconic cartoon to the nameplate of Isaiah Thomas's paper, the Massachusetts Spy, depicted there as fighting a British griffin.[22]

In December 1775, Benjamin Franklin published an essay in the Pennsylvania Journal under the pseudonym "American Guesser" in which he suggested that the rattlesnake was a good symbol for the American spirit and its valuation for vigilance, assertiveness, individualism, unity, and liberty:[23]

[...] there was painted a Rattle-Snake, with this modest motto under it, "Don't tread on me." [...] she has no eye-lids. She may therefore be esteemed an emblem of vigilance. She never begins an attack, nor, when once engaged, ever surrenders [...] The Rattle-Snake is solitary, and associates with her kind only when it is necessary for their preservation [...] 'Tis curious and amazing to observe how distinct and independent of each other the rattles of this animal are, and yet how firmly they are united together, so as never to be separated but by breaking them to pieces. [...] The power of fascination attributed to her, by a generous construction, may be understood to mean, that those who consider the liberty and blessings which America affords, and once come over to her, never afterwards leave her, but spend their lives with her.

The rattlesnake symbol was first officially adopted by the Continental Congress in 1778 when it approved the design for the seal of the War Office.[citation needed] At the top center of the seal is a rattlesnake holding a banner that says, "This we'll defend". This design of the War Office seal was carried forward—with some minor modifications—into the subsequent designs as well as the Department of the Army's seal, emblem and flag.[citation needed] As such, some variation of a rattlesnake symbol has been in continuous official use by the US Army for over 243 years.

Other American flags that use a rattlesnake motif include The United Companies of the Train of Artillery of the Town of Providence, the First Navy Jack, and the Culpeper Minutemen flag, among others.

In the 21st century, the Gadsden Flag has been used by supporters of the Tea Party movement.

History

George Washington established the Continental Navy in 1775 as Commander in Chief of the Continental Forces, before Esek Hopkins was named Commodore of the Navy. The first ships were used to intercept incoming transport ships carrying war supplies to the British in the colonies in order to supply the Continental Army, which was desperately undersupplied in the opening years of the American Revolutionary War.

Continental Colonel Christopher Gadsden represented South Carolina in the Congress, and he was one of seven members of the Marine Committee outfitting the first naval mission.[5][20]: 289 Paul Aron described Gadsden as a "leading advocate of an American navy."[24] The first Marines carried drums painted yellow and depicting a coiled rattlesnake with thirteen rattles along with the motto "Don't Tread on Me." This is the first recorded mention of the flag's symbolism.[citation needed]

Gadsden decided that the American navy needed a distinctive flag and took it upon himself to make one in 1775.[25][6] He gave Commodore Esek Hopkins a yellow rattlesnake flag to serve as his personal standard on USS Alfred, the flagship of America's first navy squadron.[7][20]: 289 Gadsden intended the design as a warning to Great Britain not to trample the liberties of its subjects.[26] The rattlesnake was seen in Charleston, South Carolina as a "noble and useful" animal that gave warning before it attacked.[5] Before being appointed to lead the Navy, Hopkins had led The United Companies of the Train of Artillery of the Town of Providence, a unit that flew a flag similar to Gadsden's.[27][28] He unfurled the Gadsden flag on the main mast of USS Alfred on December 20, 1775 while the ship was at anchor in Chesapeake Bay.[5][25] Whenever he was aboard, Hopkins flew the flag from the mainmast of the flagship as his personal banner.[5] Alfred was also the first recorded ship to fly the Grand Union Flag, the first national flag of the United States, when Senior Lieutenant John Paul Jones hoisted it on December 3, 1775 while the ship floated in the Delaware River near Philadelphia.[29][7]

By winter 1775, the South Carolina Provincial Congress expected that the British would invade Charleston and recalled Gadsden home from Congress in Philadelphia to command the 1st South Carolina Regiment.[5] By January 14, Gadsden had both his orders to return home and permission from the Continental Congress to leave.[5] On Friday, February 9, 1776, he presented an example of his yellow rattlesnake flag to president of the Congress William Henry Drayton.[5]

Gadsden's presentation of the rattlesnake flag was recorded in the South Carolina congressional journals on February 9, 1776:

Col. Gadsden presented to the Congress an elegant standard, such as is to be used by the commander in chief of the American Navy; being a yellow field, with a lively representation of a rattlesnake in the middle in the attitude of going to strike and these words underneath, "Don't tread on me."[30]

In 1861, a ship from Georgia entered Boston Harbor flying a version of the Gadsden Flag with 15 stars on it signifying the 15 slave states. The captain removed the flag after a large and angry crowd gathered, who then destroyed it. [31]

Modern use

For historical reasons, the Gadsden flag is still popularly flown in Charleston, South Carolina, the city where Christopher Gadsden first presented the flag and where it was commonly used during the revolution, along with the blue and white crescent flag of pre-Civil War South Carolina.

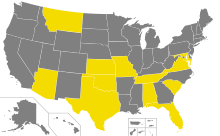

The Gadsden flag has become a popular specialty license plate in several states. As of 2022[update], the following states offer the option of obtaining a Gadsden flag specialty license plate: Alabama, Arizona,[32] Florida,[33][34] Kansas,[35] Maryland,[36] Missouri, Montana,[37] Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee,[38] Texas, and Virginia.[39][40]

Use as a libertarian symbol

In the 1970s the Gadsden flag started being used by libertarians, using it as a symbol representing individual rights and limited government.[41] The flag's prominent yellow color is also strongly associated with libertarianism.[42] The libertarian Free State Project uses a modified version of the flag with the snake replaced with a porcupine, a symbol of the movement.[43][unreliable source?]

Used in a terrorist act

In 2014, the flag was used by Jerad and Amanda Miller, the perpetrators of the 2014 Las Vegas shootings who killed two police officers and a civilian.[44] The Millers reportedly placed the Gadsden Flag on the corpse of one of the officers they killed.[45]

Use by the left

In the mid-1970s, the New Left People's Bicentennial Commission used the Gadsden Flag symbolism on buttons and literature.[46][47]

Use by the right

The Gadsden flag has also been used by groups and individuals on the right. The Gadsden flag was featured prominently in a report related to the January 6, 2021 storming of the United States Capitol.[48][b]

Use as a symbol of the Tea Party movement

Beginning in 2009, the Gadsden flag was widely used as a protest symbol by protesters who supported the American Tea Party movement.[51][52][53] It was also displayed by members of Congress at Tea Party rallies.[54] In some cases, the flag was ruled to be a political, rather than a historic or military, symbol due to the strong Tea Party connection.[55]

Legal cases involving the Gadsden flag

In March 2013, the Gadsden flag was raised at a vacant armory building in New Rochelle, New York without permission from city officials. The city ordered its removal[56] and the United Veterans Memorial & Patriotic Association, which had maintained the U.S. flag at the armory, filed suit against the city. A federal judge dismissed the case, rejecting the United Veterans' First Amendment argument and ruling that the flagpole in question was city property and thus did not represent private speech.[57]

In 2014, a US Postal Service employee filed a complaint about a coworker repeatedly wearing a hat with a Gadsden Flag motif at work. Postal service administration dismissed the complaint, but the United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission reversed the decision and called for a careful investigation. The EEOC issued a statement clarifying that it did not make any decision that the Gadsden flag was a "racist symbol," or that wearing a depiction of it constituted racial discrimination.[58]

Rainbow version

Street Patrol, a 1990s queer self-defense group affiliated with Queer Nation/San Francisco, used as its logo a coiled snake over a triangle holding a ribbon with the motto "Don't Tread on Me".[59][60] Some libertarian circles use a version of the flag with the snake and motto placed over a rainbow flag.[61] Following the 2016 Orlando nightclub shooting, posters containing a rainbow Gadsden flag inscribed with "#ShootBack" were placed around West Hollywood.[62]

Use outside the U.S.

The Gadsden flag has been co-opted by supporters of Argentine right-libertarian presidential candidate Javier Milei. [63]

Appearances in popular culture

The Gadsden flag has made numerous appearances in popular culture, particularly in post-apocalyptic stories.

In film and television

- In the 1982 film Tootsie, the character of Jeff Slater (Bill Murray) is shown to have the Gadsden flag displayed in his bedroom.

- In the 1985 film “Rocky IV”, the character of Paulie (Burt Young) wears a coat with the flag on the back while in Russia.

- In the 1995 The Simpsons episode "Bart vs. Australia", Bart reveals in an act of "patriotism" the phrase "Don't Tread On Me" written across his buttocks when he is supposed to be kicked by the Australian Prime Minister as a punishment.

- In the 2006 CBS apocalyptic drama series Jericho, Gadsden flags are shown several times, most notably in the series finale when Jericho's mayor, Gray Anderson (Michael Gaston), replaces the town hall's "Allied States of America" flag with a Gadsden flag.[64]

- In the 2009 NBC mockumentary sitcom Parks and Recreation, Ron Swanson (Nick Offerman) has a miniature Gadsden flag in his office.[65]

- In the 2023 HBO apocalyptic drama series The Last of Us, Bill (Nick Offerman) has a Gadsden flag in his house.[66]

In music

- American heavy metal band Metallica recorded a song called "Don't Tread on Me" on their self-titled fifth studio album, released in 1991. The album cover features a dark-gray picture of a coiled rattlesnake like the one found on the Gadsden Flag.[67]

Notes

References

- ^ Waser, Thomas (December 6, 2016). "The Symbolism of the Timber-Rattlesnake in Early America". Herpetology Guy (Thomas Waser) on Steemit. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

- ^ "Timber Rattlesnake Conservation Strategy for Pennsylvania State Forest Lands". Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. April 7, 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

- ^ Lowth, Robert (1794). A Short Introduction to English Grammar: With Critical Notes. pp. 67, 79.

- ^ "GADSDEN, Christopher | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Godbold Jr., E. Stanly; Woody, Robert Hilliard (1982). Christopher Gadsden and the American Revolution. Univ. of Tennessee Press. pp. 142–150. ISBN 978-0-87049-363-8.

- ^ a b c "Short History of the United States Flag". American Battlefield Trust. November 6, 2019. Archived from the original on February 15, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Alfred". Naval History and Heritage Command. U.S. Navy. June 9, 2022. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

Alfred, Hopkins' flagship, was placed in commission on 3 December 1775

- ^ "Esek Hopkins appointed Commander-in-Chief of Continental Navy". California SAR. Archived from the original on February 20, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ "Join, or Die". Pennsylvania Gazette. Philadelphia. May 9, 1754. p. 2. Retrieved January 19, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Rattlesnake as a Symbol of America - by Benjamin Franklin". greatseal.com. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ^ "Top 23 Symbols of Freedom & Liberty Throughout History". Give Me History. November 25, 2020.

- ^ Nicholson, Katie (February 15, 2022). "From snakes to Spartans: The meaning behind some of the flags convoy protesters are carrying". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ Miller, Matthew M. F. (November 20, 2020). "The Radical Individualism Raging Throughout America". Shondaland. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ Robertson, Marcella (October 28, 2020). "Confederate flag along I-95 in Stafford removed, replaced with 'Don't Tread On Me' flag". WUSA9.

- ^ Bosso, Joe (June 25, 2012). "James Hetfield, Kirk Hammett reflect on Metallica's Black Album". MusicRadar. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ Scocca, Tom. "Flag daze". The Boston Globe. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ Template:Title=Yellow Gadsden Flag Carries a Long and Shifting History

- ^ Neuman, Scott (August 10, 2022). "A Florida license plate has reopened the debate over the 'Don't tread on me' flag". NPR. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ Rosenberg, Matthew; Tiefenthäler, Ainara (January 13, 2021). "Decoding the Far-Right Symbols at the Capitol Riot". The New York Times. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ a b c McCandless, Byron; Gilbert Hovey Grosvenor (1917). Our flag number: with 1197 flags in full colors and 300 additional illustrations in black and white. National Geographic Society. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Leepson, Marc; DeMille, Nelson (May 30, 2006). Flag: An American Biography. Macmillan. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-312-32309-7. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "A More Perfect Union: Symbolizing the National Union of States". Library of Congress. July 23, 2010. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Franklin, Benjamin (December 27, 1775). "The Rattlesnake as a Symbol of America". The Franklin Institute. Archived from the original on August 15, 2000.

- ^ Aron, Paul (2008). We Hold These Truths...: And Other Words That Made America. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-7425-6273-8.

- ^ a b McDonough, Daniel J. (2000). Christopher Gadsden and Henry Laurens: The Parallel Lives of Two American Patriots. Susquehanna University Press. pp. 169–173. ISBN 978-1-57591-039-0.

- ^ Godbold, E.; Woody, Robert (January 1982). Christopher Gadsden and the American Revolution. The University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 0-87049-362-0.

- ^ "United Company of the Train of Artillery (U.S.)". www.crwflags.com. Archived from the original on December 8, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ "Flag of the United Train of Artillery of Providence". The Monticello Classroom. January 28, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ^ Rankin, Hugh F. “The Naval Flag of the American Revolution.” William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 11, no. 3, 1954, pp. 340–53. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1943310. Accessed 20 Feb. 2023.

- ^ Hicks, Frederick Cocks (1918). The flag of the United States. United States Government Printing Office. p. 23. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "The disgraced Confederate history of the 'Don't Tread on Me' flag". Washington Post. Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- ^ "2020 Arizona Revised Statutes :: Title 28 - Transportation :: § 28-2439 Don't tread on me special plates". Justia Law. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Neuman, Scott (August 10, 2022). "A Florida license plate has reopened the debate over the 'Don't tread on me' flag". NPR. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ Abad, Dylan (August 2, 2022). "Florida's new 'Don't Tread On Me' license plate stirs controversy". WFLA-TV. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- ^ Taborda, Noah (April 12, 2021). "Kansas Legislature endorses Gadsden flag license plate supporting state rifle association". Kansas Reflector. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ "Gadsden Pew Club license plate". Maryland Motor Vehicle Administration. Archived from the original on January 31, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ^ "Service Organizations & Associations". Montana Department of Justice.

- ^ "Friends of Sycamore Shoals State Historic Park". friendsofsycamoreshoals.org. Archived from the original on December 14, 2018. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "Seven States Now Offer 'Don't Tread on Me' License Plates; Is Yours on the List? - Tea Party News". Tea Party. Archived from the original on August 12, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Schwarz, Hunter (August 25, 2014). "States where you can get a 'Don't Tread On Me' license plate". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Walker, Rob. "The Shifting Symbolism of the Gadsden Flag". The New Yorker. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ Sawer, Marian (April 18, 2007). "Wearing your Politics on your Sleeve: The Role of Political Colors in Social Movements". Social Movement Studies. 6 (1): 39–56. doi:10.1080/14742830701251294. ISSN 1474-2837. S2CID 145495971.

- ^ Doherty, Brian (November 16, 2016). "Free State Project Supporter Shot in Fight That Began Over Its Porcupine Flag". Reason. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ "Las Vegas shooting suspects left swastika, 'Don't tread on me' flag on dead officers". CBS News.

- ^ "Two Cops, Three Others Killed in Las Vegas Shooting Spree". NBC News. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ^ Hall, Simon. "'Guerrilla-Theater... In the Guise of Red, White, and Blue Bunting': The People's bicentennial Commission and the Politics of (Un-)Americanism. Journal of American Studies, Vol. 52, No. 1 (February 2018); pp. 114–136. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018; pp. 114-136

- ^ Daly, Christopher. "The Peoples Bicentennial Commission: Slouching Towards the Economic Revolution" The Harvard Crimson April 28, 1975

- ^ Rosenberg, Matthew; Tiefenthäler, Ainara (January 13, 2021). "Decoding the Far-Right-Symbols at the Capitol-Riot". The New York Times. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ Melendez, Pilar (April 7, 2021). "Capitol Rioter Rosanne Boyland died from Drug-Overdose, not trampling". The Daily Beast.

- ^ "Death of QAnon-Follower at Capitol leaves a Wake of Pain". The New York Times. May 30, 2021. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ "Gadsden flag denied over State Capitol". New Haven, Connecticut: WTNH. May 26, 2010. Archived from the original on January 13, 2011. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- ^ Hayes, Ted (May 27, 2010). "'Tea Party' flag rankles some". East Bay Newspapers. Archived from the original on June 11, 2010. Retrieved September 7, 2011.

- ^ Macedo, Diane (April 7, 2010). "Connecticut Marines Fight for 'Don't Tread on Me' Flag Display". Fox News. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ^ "Gadsden Flags Flying Off the Shelves in Support of the Tea Party Tax Protest" (Press release). FlagandBanner.com. Marketwire. April 16, 2009. Archived from the original on August 14, 2009. Retrieved July 7, 2009 – via Reuters.

- ^ "Tea Party flag will not fly at Connecticut Capitol". NECN. April 8, 2010. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ^ "Flag's Believed Ties To Tea Party Lead To Removal From New Rochelle Building". CBS 2 New York. April 22, 2013. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "New Rochelle veterans lose Gadsden flag case". The Journal News / Lohud. December 24, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ "What You Should Know about EEOC and Shelton D. v. U.S. Postal Service (Gadsden Flag case)". U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Miles, Sara (July 1, 1992). "The Fabulous Fight Back". Outlook (17): 57, 59. OCLC 17286887.

- ^ Collie, Robert (April 29, 1991). "Squad patrols Castro for gay-bashers". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ "Gadsden Flag (U.S.)". Flags of the World. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ Branson-Potts, Hailey (June 16, 2016). "West Hollywood plastered with rainbow #ShootBack signs". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ "Far-right outsider takes shock lead in Argentina primary election". TheGuardian.com.

- ^ "Jericho Video – Jericho – Season 2: Episode 7: Patriots And Tyrants w/ Commentary". CBS. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "Parks And Rec: 10 Hidden Details About Ron Swanson's Office". ScreenRant. November 14, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ^ MacLeod, Riley (January 29, 2023). "'The Last of Us' tells a new but familiar queer love story". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- ^ Masciotra, David (2015). Metallica. 33 1/3. Vol. 108. Bloomsbury. p. 65.

External links

![]() Media related to Gadsden flag at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gadsden flag at Wikimedia Commons

- Activism flags

- Continental Marines

- Flags displaying animals

- Flags of the American Revolution

- Flags of the United States

- Historical flags

- History of the Thirteen Colonies

- Liberty symbols

- Military flags of the United States

- Political Internet memes

- Snakes in art

- Tea Party movement

- United States Marine Corps in the 18th and 19th centuries

- Libertarianism in the United States