Fast inverse square root: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 153: | Line 153: | ||

===Aliasing to an integer as an approximate logarithm=== |

===Aliasing to an integer as an approximate logarithm=== |

||

If |

If <math>\frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}</math> were to be calculated without a computer or a calculator, a [[table of logarithms]] would be useful, together with the identity <math>\log_b(\frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}) = \log_b(x^{-\frac{1}{2}}) = -\frac{1}{2} \log_b(x)</math>, which is valid for every base <math>b</math>. The fast inverse square root is based on this identity, and on the fact that aliasing a float32 to an integer gives a rough approximation of its logarithm. Here is how: |

||

If |

If <math>x</math> is a positive [[Normal number (computing)|normal number]]: |

||

:<math>x = 2^{e_x} (1 + m_x)</math> |

:<math>x = 2^{e_x} (1 + m_x)</math> |

||

| Line 163: | Line 163: | ||

:<math>\log_2(x) = e_x + \log_2(1 + m_x)</math> |

:<math>\log_2(x) = e_x + \log_2(1 + m_x)</math> |

||

and since |

and since <math>m_x \in [0, 1)</math>, the logarithm on the right hand side can be approximated by{{Sfn|McEniry|2007|p=3}} |

||

:<math>\log_2(1 + m_x) \approx m_x + \sigma</math> |

:<math>\log_2(1 + m_x) \approx m_x + \sigma</math> |

||

where |

where <math>\sigma</math> is a free parameter used to tune the approximation. For example, <math>\sigma = 0</math> yields exact results at both ends of the interval, while <math>\sigma = \frac{1}{2} - \frac{1+\ln(\ln(2))}{2\ln(2)} \approx 0.0430357</math> yields the [[Approximation theory#Optimal polynomials|optimal approximation]] (the best in the sense of the [[uniform norm]] of the error). |

||

[[File:Log_by_aliasing_to_int.svg|thumb|right|The integer aliased to a floating point number (in blue), compared to a scaled and shifted logarithm (in gray).]] |

[[File:Log_by_aliasing_to_int.svg|thumb|right|The integer aliased to a floating point number (in blue), compared to a scaled and shifted logarithm (in gray).]] |

||

| Line 175: | Line 175: | ||

:<math>\log_2(x) \approx e_x + m_x + \sigma.</math> |

:<math>\log_2(x) \approx e_x + m_x + \sigma.</math> |

||

Interpreting the floating-point bit-pattern of |

Interpreting the floating-point bit-pattern of <math>x</math> as an integer <math>I_x</math> yields<ref group=note>Since <math>x</math> is positive, <math>S_x = 0</math>.</ref> |

||

:<math>\begin{align} |

:<math>\begin{align} |

||

| Line 184: | Line 184: | ||

\end{align}</math> |

\end{align}</math> |

||

It then appears that |

It then appears that <math>I_x</math> is a scaled and shifted piecewise-linear approximation of <math>\log_2(x)</math>, as illustrated in the figure on the right. In other words, <math>\log_2(x)</math> is approximated by |

||

:<math>\log_2(x) \approx \frac{I_x}{L} - (B - \sigma).</math> |

:<math>\log_2(x) \approx \frac{I_x}{L} - (B - \sigma).</math> |

||

===First approximation of the result=== |

===First approximation of the result=== |

||

The calculation of |

The calculation of <math>y=\frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}</math> is based on the identity |

||

:<math>\log_2(y) = - \tfrac{1}{2}\log_2(x)</math> |

:<math>\log_2(y) = - \tfrac{1}{2}\log_2(x)</math> |

||

Using the approximation of the logarithm above, applied to both |

Using the approximation of the logarithm above, applied to both <math>x</math> and <math>y</math>, the above equation gives: |

||

:<math>\frac{I_y}{L} - (B - \sigma) \approx - \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{I_x}{L} - (B - \sigma)\right)</math> |

:<math>\frac{I_y}{L} - (B - \sigma) \approx - \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{I_x}{L} - (B - \sigma)\right)</math> |

||

Thus, an approximation of |

Thus, an approximation of <math>I_y</math> is: |

||

:<math>I_y \approx \tfrac{3}{2} L (B - \sigma) - \tfrac{1}{2} I_x</math> |

:<math>I_y \approx \tfrac{3}{2} L (B - \sigma) - \tfrac{1}{2} I_x</math> |

||

| Line 209: | Line 209: | ||

:<math>\tfrac{3}{2} L (B - \sigma) = \mathtt{0x5F3759DF}</math> |

:<math>\tfrac{3}{2} L (B - \sigma) = \mathtt{0x5F3759DF}</math> |

||

from which it can be inferred that |

from which it can be inferred that <math>\sigma \approx 0.0450466</math>. The second term, <math>\frac{1}{2}I_x</math>, is calculated by shifting the bits of <math>I_x</math> one position to the right.{{sfn|Hennessey|Patterson|1998|p=305}} |

||

===Newton's method=== |

===Newton's method=== |

||

| Line 225: | Line 225: | ||

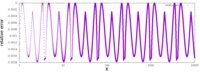

| footer = Relative error between direct calculation and fast inverse square root carrying out 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 iterations of Newton's root-finding method. Note that double precision is adopted and the smallest representable difference between two double precision numbers is reached after carrying out 4 iterations. |

| footer = Relative error between direct calculation and fast inverse square root carrying out 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 iterations of Newton's root-finding method. Note that double precision is adopted and the smallest representable difference between two double precision numbers is reached after carrying out 4 iterations. |

||

}} |

}} |

||

With |

With <math>y</math> as the inverse square root, <math>f(y)=\frac{1}{y^2}-x=0</math>. The approximation yielded by the earlier steps can be refined by using a [[root-finding method]], a method that finds the [[zero of a function]]. The algorithm uses [[Newton's method]]: if there is an approximation, <math>y_n</math> for <math>y</math>, then a better approximation <math>y_{n+1}</math> can be calculated by taking <math>y_n - \frac{f(y_n)}{f\prime(y_n)}</math>, where <math>f\prime(y_n)</math> is the [[derivative]] of <math>f(y)</math> at <math>y_n</math>.{{Sfn|Hardy|1908|p=323}} For the above <math>f(y)</math>, |

||

:<math>y_{n+1} = \frac{y_{n}\left(3-xy_n^2\right)}{2}</math> |

:<math>y_{n+1} = \frac{y_{n}\left(3-xy_n^2\right)}{2}</math> |

||

where |

where <math>f(y)= \frac{1}{y_2} - x</math> and <math>f(y) = -\frac{2}{y_3}</math>. |

||

Treating |

Treating <math>y</math> as a floating-point number, <code>y = y*(threehalfs - x/2*y*y);</code> is equivalent to |

||

:<math>y_{n+1} = y_{n}\left (\frac32-\frac{x}{2}y_n^2\right ) = \frac{y_{n}\left(3-xy_n^2\right)}{2}.</math> |

:<math>y_{n+1} = y_{n}\left (\frac32-\frac{x}{2}y_n^2\right ) = \frac{y_{n}\left(3-xy_n^2\right)}{2}.</math> |

||

By repeating this step, using the output of the function ( |

By repeating this step, using the output of the function (<math>y_{n+1}</math>) as the input of the next iteration, the algorithm causes <math>y</math> to [[Rate of convergence|converge]] to the inverse square root.{{Sfn|McEniry|2007|p=6}} For the purposes of the [[id Tech 3|''Quake III'' engine]], only one iteration was used. A second iteration remained in the code but was [[Comment out|commented out]].{{Sfn|Eberly|2001|p=2}} |

||

===Accuracy=== |

===Accuracy=== |

||

| Line 242: | Line 242: | ||

==Subsequent improvements== |

==Subsequent improvements== |

||

===Magic number=== |

===Magic number=== |

||

It is not known precisely how the exact value for the magic number was determined. Chris Lomont developed a function to minimize [[approximation error]] by choosing the magic number |

It is not known precisely how the exact value for the magic number was determined. Chris Lomont developed a function to minimize [[approximation error]] by choosing the magic number <math>R</math> over a range. He first computed the optimal constant for the linear approximation step as {{mono|0x5F37642F}}, close to {{mono|0x5F3759DF}}, but this new constant gave slightly less accuracy after one iteration of Newton's method.{{Sfn|Lomont|2003|p=10}} Lomont then searched for a constant optimal even after one and two Newton iterations and found {{mono|0x5F375A86}}, which is more accurate than the original at every iteration stage.{{Sfn|Lomont|2003|p=10}} He concluded by asking whether the exact value of the original constant was chosen through derivation or [[trial and error]].{{Sfn|Lomont|2003|pp=10–11}} Lomont said that the magic number for 64-bit IEEE754 size type double is {{mono|0x5FE6EC85E7DE30DA}}, but it was later shown by Matthew Robertson to be exactly {{mono|0x5FE6EB50C7B537A9}}.<ref name="robertson" /> |

||

Jan Kadlec reduced the relative error by a further factor of 2.7<!--Rounded from 2.693495--> by adjusting the constants in the single Newtons's method iteration as well,<ref>{{cite web |

Jan Kadlec reduced the relative error by a further factor of 2.7<!--Rounded from 2.693495--> by adjusting the constants in the single Newtons's method iteration as well,<ref>{{cite web |

||

Revision as of 18:24, 16 August 2021

Fast inverse square root, sometimes referred to as Fast InvSqrt() or by the hexadecimal constant 0x5F3759DF, is an algorithm that estimates , the reciprocal (or multiplicative inverse) of the square root of a 32-bit floating-point number in IEEE 754 floating-point format. This operation is used in digital signal processing to normalize a vector, i.e., scale it to length 1. For example, computer graphics programs use inverse square roots to compute angles of incidence and reflection for lighting and shading. The algorithm is best known for its implementation in 1999 in the source code of Quake III Arena, a first-person shooter video game that made heavy use of 3D graphics. The algorithm only started appearing on public forums such as Usenet in 2002 or 2003.[1][note 1] At the time, it was generally computationally expensive to compute the reciprocal of a floating-point number, especially on a large scale; the fast inverse square root bypassed this step.

The algorithm accepts a 32-bit floating-point number as the input and stores a halved value for later use. Then, treating the bits representing the floating-point number as a 32-bit integer, a logical shift right by one bit is performed and the result subtracted from the number 0x5F3759DF, which is a floating point representation of an approximation of .[3] This results in the first approximation of the inverse square root of the input. Treating the bits again as a floating-point number, it runs one iteration of Newton's method, yielding a more precise approximation.

The algorithm was originally attributed to John Carmack, but an investigation showed that the code had deeper roots in both the hardware and software side of computer graphics. Adjustments and alterations passed through both Silicon Graphics and 3dfx Interactive, with Gary Tarolli's implementation for the SGI Indigo as the earliest known use. Investigation has shed some light on the original constant being derived via a collaboration between Cleve Moler and Gregory Walsh, while Gregory was working for Ardent Computing in the early 1980s.[4]

With subsequent hardware advancements, especially the x86 SSE instruction rsqrtss, this method is not generally applicable to modern computing,[5] though it remains an interesting example both historically[6] and for more limited machines, such as low-cost embedded systems. However, more manufacturers of embedded systems are including trigonometric and other math accelerators such as CORDIC, obviating the need for such algorithms.

Motivation

The inverse square root of a floating point number is used in calculating a normalized vector.[7] Programs can use normalized vectors to determine angles of incidence and reflection. 3D graphics programs must perform millions of these calculations every second to simulate lighting. When the code was developed in the early 1990s, most floating-point processing power lagged behind the speed of integer processing.[1] This was troublesome for 3D graphics programs before the advent of specialized hardware to handle transform and lighting.

The length of the vector is determined by calculating its Euclidean norm: the square root of the sum of squares of the vector components. When each component of the vector is divided by that length, the new vector will be a unit vector pointing in the same direction. In a 3D graphics program, all vectors are in three-dimensional space, so would be a vector .

is the Euclidean norm of the vector.

is the normalized (unit) vector, using to represent .

which relates the unit vector to the inverse square root of the distance components. The inverse square root can be used to compute because this equation is equivalent to

where the fraction term is the inverse square root of .

At the time, floating-point division was generally expensive compared to multiplication; the fast inverse square root algorithm bypassed the division step, giving it its performance advantage. Quake III Arena, a first-person shooter video game, used the fast inverse square root algorithm to accelerate graphics computation, but the algorithm has since been implemented in some dedicated hardware vertex shaders using field-programmable gate arrays (FPGA).[8]

Overview of the code

The following code is the fast inverse square root implementation from Quake III Arena, stripped of C preprocessor directives, but including the exact original comment text:[9]

float Q_rsqrt( float number )

{

long i;

float x2, y;

const float threehalfs = 1.5F;

x2 = number * 0.5F;

y = number;

i = * ( long * ) &y; // evil floating point bit level hacking

i = 0x5f3759df - ( i >> 1 ); // what the fuck?

y = * ( float * ) &i;

y = y * ( threehalfs - ( x2 * y * y ) ); // 1st iteration

// y = y * ( threehalfs - ( x2 * y * y ) ); // 2nd iteration, this can be removed

return y;

}

At the time, the general method to compute the inverse square root was to calculate an approximation for , then revise that approximation via another method until it came within an acceptable error range of the actual result. Common software methods in the early 1990s drew approximations from a lookup table.[10] The key of the fast inverse square root was to directly compute an approximation by utilizing the structure of floating-point numbers, proving faster than table lookups. The algorithm was approximately four times faster than computing the square root with another method and calculating the reciprocal via floating-point division.[11] The algorithm was designed with the IEEE 754-1985 32-bit floating-point specification in mind, but investigation from Chris Lomont showed that it could be implemented in other floating-point specifications.[12]

The advantages in speed offered by the fast inverse square root trick came from treating the 32-bit floating-point word[note 2] as an integer, then subtracting it from a "magic" constant, 0x5F3759DF.[1][13][14][15] This integer subtraction and bit shift results in a bit pattern which, when re-defined as a floating-point number, is a rough approximation for the inverse square root of the number. One iteration of Newton's method is performed to gain some accuracy, and the code is finished. The algorithm generates reasonably accurate results using a unique first approximation for Newton's method; however, it is much slower and less accurate than using the SSE instruction rsqrtss on x86 processors also released in 1999.[5][16]

According to the C standard, reinterpreting a floating point value as an integer by removing the pointer to it is considered to be able to cause unexpected behavior (undefined behavior). This problem could be circumvented using the library function memcpy. The following code follows C standards, though at the cost of needing an additional variable, and needing more memory: the floating point value is placed in an anonymous union containing an additional 32-bit unsigned integer member, and accesses to that integer provides a bit level view of the contents of the floating point value.

#include <stdint.h> // uint32_t

float Q_rsqrt( float number )

{

const float x2 = number * 0.5F;

const float threehalfs = 1.5F;

union {

float f;

uint32_t i;

} conv = { .f = number };

conv.i = 0x5f3759df - ( conv.i >> 1 );

conv.f *= threehalfs - ( x2 * conv.f * conv.f );

return conv.f;

}

However, type punning through a union is undefined behavior in C++. A correct method for doing this in C++ is through std::bit_cast. That also allows the function to work in constexpr context.

//only works after C++20 standard

#include <bit>

#include <limits>

#include <cstdint>

constexpr float Q_rsqrt(float number) noexcept

{

static_assert(std::numeric_limits<float>::is_iec559); // (enable only on IEEE 754)

float const y = std::bit_cast<float>(

0x5f3759df - (std::bit_cast<std::uint32_t>(number) >> 1));

return y * (1.5f - (number * 0.5f * y * y));

}

Worked example

As an example, the number can be used to calculate . The first steps of the algorithm are illustrated below:

0011_1110_0010_0000_0000_0000_0000_0000 Bit pattern of both x and i 0001_1111_0001_0000_0000_0000_0000_0000 Shift right one position: (i >> 1) 0101_1111_0011_0111_0101_1001_1101_1111 The magic number 0x5F3759DF 0100_0000_0010_0111_0101_1001_1101_1111 The result of 0x5F3759DF - (i >> 1)

Interpreting as IEEE 32-bit representation:

0_01111100_01000000000000000000000 1.25 × 2−3 0_00111110_00100000000000000000000 1.125 × 2−65 0_10111110_01101110101100111011111 1.432430... × 263 0_10000000_01001110101100111011111 1.307430... × 21

Reinterpreting this last bit pattern as a floating point number gives the approximation , which has an error of about 3.4%. After one single iteration of Newton's method, the final result is , an error of only 0.17%.

Algorithm

The algorithm computes by performing the following steps:

- Alias the argument to an integer as a way to compute an approximation of the binary logarithm

- Use this approximation to compute an approximation of

- Alias back to a float, as a way to compute an approximation of the base-2 exponential

- Refine the approximation using a single iteration of Newton's method.

Floating-point representation

Since this algorithm relies heavily on the bit-level representation of single-precision floating-point numbers, a short overview of this representation is provided here. In order to encode a non-zero real number as a single precision float, the first step is to write as a normalized binary number:[17]

where the exponent is an integer, , and is the binary representation of the "significand" . Since the single bit before the point in the significand is always 1, it need not be stored. From this form, three unsigned integers are computed:[18]

- , the "sign bit", is if is positive and negative or zero (1 bit)

- is the "biased exponent", where is the "exponent bias"[note 3] (8 bits)

- , where [note 4] (23 bits)

These fields are then packed, left to right, into a 32-bit container.[19]

As an example, consider again the number . Normalizing yields:

and thus, the three unsigned integer fields are:

these fields are packed as shown in the figure below:

Aliasing to an integer as an approximate logarithm

If were to be calculated without a computer or a calculator, a table of logarithms would be useful, together with the identity , which is valid for every base . The fast inverse square root is based on this identity, and on the fact that aliasing a float32 to an integer gives a rough approximation of its logarithm. Here is how:

If is a positive normal number:

then

and since , the logarithm on the right hand side can be approximated by[20]

where is a free parameter used to tune the approximation. For example, yields exact results at both ends of the interval, while yields the optimal approximation (the best in the sense of the uniform norm of the error).

Thus there is the approximation

Interpreting the floating-point bit-pattern of as an integer yields[note 5]

It then appears that is a scaled and shifted piecewise-linear approximation of , as illustrated in the figure on the right. In other words, is approximated by

First approximation of the result

The calculation of is based on the identity

Using the approximation of the logarithm above, applied to both and , the above equation gives:

Thus, an approximation of is:

which is written in the code as

i = 0x5f3759df - ( i >> 1 );

The first term above is the magic number

from which it can be inferred that . The second term, , is calculated by shifting the bits of one position to the right.[21]

Newton's method

With as the inverse square root, . The approximation yielded by the earlier steps can be refined by using a root-finding method, a method that finds the zero of a function. The algorithm uses Newton's method: if there is an approximation, for , then a better approximation can be calculated by taking , where is the derivative of at .[22] For the above ,

where and .

Treating as a floating-point number, y = y*(threehalfs - x/2*y*y); is equivalent to

By repeating this step, using the output of the function () as the input of the next iteration, the algorithm causes to converge to the inverse square root.[23] For the purposes of the Quake III engine, only one iteration was used. A second iteration remained in the code but was commented out.[15]

Accuracy

As noted above, the approximation is surprisingly accurate. The single graph on the right plots the error of the function (that is, the error of the approximation after it has been improved by running one iteration of Newton's method), for inputs starting at 0.01, where the standard library gives 10.0 as a result, while InvSqrt() gives 9.982522, making the difference 0.017479, or 0.175% of the true value, 10. The absolute error only drops from then on, while the relative error stays within the same bounds across all orders of magnitude.

History

The source code for Quake III was not released until QuakeCon 2005, but copies of the fast inverse square root code appeared on Usenet and other forums as early as 2002 or 2003.[1] Initial speculation pointed to John Carmack as the probable author of the code, but he demurred and suggested it was written by Terje Mathisen, an accomplished assembly programmer who had previously helped id Software with Quake optimization. Mathisen had written an implementation of a similar bit of code in the late 1990s, but the original authors proved to be much further back in the history of 3D computer graphics with Gary Tarolli's implementation for the SGI Indigo as a possible earliest known use. Rys Sommefeldt concluded that the original algorithm was devised by Greg Walsh at Ardent Computer in consultation with Cleve Moler, the creator of MATLAB.[24] Cleve Moler learned about this trick from code written by William Kahan and K.C. Ng at Berkeley around 1986.[25] Jim Blinn also demonstrated a simple approximation of the inverse square root in a 1997 column for IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications.[26][27] Paul Kinney implemented a fast method for the FPS T Series computer[28] around 1986. The system included vector floating-point hardware which was not rich in integer operations. The floating-point values were floated to allow manipulation to create the initial approximation.

Subsequent improvements

Magic number

It is not known precisely how the exact value for the magic number was determined. Chris Lomont developed a function to minimize approximation error by choosing the magic number over a range. He first computed the optimal constant for the linear approximation step as 0x5F37642F, close to 0x5F3759DF, but this new constant gave slightly less accuracy after one iteration of Newton's method.[29] Lomont then searched for a constant optimal even after one and two Newton iterations and found 0x5F375A86, which is more accurate than the original at every iteration stage.[29] He concluded by asking whether the exact value of the original constant was chosen through derivation or trial and error.[30] Lomont said that the magic number for 64-bit IEEE754 size type double is 0x5FE6EC85E7DE30DA, but it was later shown by Matthew Robertson to be exactly 0x5FE6EB50C7B537A9.[31]

Jan Kadlec reduced the relative error by a further factor of 2.7 by adjusting the constants in the single Newtons's method iteration as well,[32] arriving after an exhaustive search at

conv.i = 0x5F1FFFF9 - ( conv.i >> 1 );

conv.f *= 0.703952253f * ( 2.38924456f - x * conv.f * conv.f );

return conv.f;

A complete mathematical analysis for determining the magic number is now available for single-precision floating-point numbers.[33]

Zero finding

Intermediate to the use of one vs. two iterations of Newton's method in terms of speed and accuracy is a single iteration of Halley's method. In this case, Halley's method is equivalent to applying Newton's method with the starting formula . The update step is then

where the implementation should calculate only once, via a temporary variable.

See also

- Methods of computing square roots § Approximations that depend on the floating point representation

- Magic number

Notes

- ^ There was a discussion on the Chinese developer forum CSDN back in 2000.[2]

- ^ Use of the type

longreduces the portability of this code on modern systems. For the code to execute properly,sizeof(long)must be 4 bytes, otherwise negative outputs may result. Under many modern 64-bit systems,sizeof(long)is 8 bytes. The more portable replacement isint32_t. - ^ should be in the range for to be representable as a normal number.

- ^ The only real numbers that can be represented exactly as floating point are those for which is an integer. Other numbers can only be represented approximately by rounding them to the nearest exactly representable number.

- ^ Since is positive, .

References

- ^ a b c d Sommefeldt, Rys (2006-11-29). "Origin of Quake3's Fast InvSqrt()". Beyond3D. Retrieved 2009-02-12.

- ^ "Discussion on CSDN". Archived from the original on 2015-07-02.

- ^ Munafo, Robert. "Notable Properties of Specific Numbers". mrob.com. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018.

- ^ "Beyond3D - Origin of Quake3's Fast InvSqrt() - Part Two". www.beyond3d.com. Retrieved 2021-07-03.

A big thanks to Greg for saying hello and passing on his information, and big thanks to Slashdot (and Geo for the slashvertising submission) since without the big publicity, Greg might never have seen the original article.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Ruskin, Elan (2009-10-16). "Timing square root". Some Assembly Required. Archived from the original on 2021-02-08. Retrieved 2015-05-07.

- ^ feilipu. "z88dk is a collection of software development tools that targets the 8080 and z80 computers".

- ^ Blinn 2003, p. 130.

- ^ Middendorf 2007, pp. 155–164.

- ^ "quake3-1.32b/code/game/q_math.c". Quake III Arena. id Software. Retrieved 2017-01-21.

- ^ Eberly 2001, p. 504.

- ^ Lomont 2003, p. 1.

- ^ Lomont 2003.

- ^ Lomont 2003, p. 3.

- ^ McEniry 2007, p. 2, 16.

- ^ a b Eberly 2001, p. 2.

- ^ Fog, Agner. "Lists of instruction latencies, throughputs and micro-operation breakdowns for Intel, AMD and VIA CPUs" (PDF). Retrieved 2017-09-08.

- ^ Goldberg 1991, p. 7.

- ^ Goldberg 1991, pp. 15–20.

- ^ Goldberg 1991, p. 16.

- ^ McEniry 2007, p. 3.

- ^ Hennessey & Patterson 1998, p. 305.

- ^ Hardy 1908, p. 323.

- ^ McEniry 2007, p. 6.

- ^ Sommefeldt, Rys (2006-12-19). "Origin of Quake3's Fast InvSqrt() - Part Two". Beyond3D. Retrieved 2008-04-19.

- ^ Moler, Cleve. "Symplectic Spacewar". MATLAB Central - Cleve's Corner. MATLAB. Retrieved 2014-07-21.

- ^ Blinn 1997, pp. 80–84.

- ^ "sqrt implementation in fdlibm".

- ^ Fazzari, Rod; Miles, Doug; Carlile, Brad; Groshong, Judson (1988). "A New Generation of Hardware and Software for the FPS T Series". Proceedings of the 1988 Array Conference: 75–89.

- ^ a b Lomont 2003, p. 10.

- ^ Lomont 2003, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Matthew Robertson (2012-04-24). "A Brief History of InvSqrt" (PDF). UNBSJ.

- ^ Kadlec, Jan (2010). "Řrřlog::Improving the fast inverse square root" (personal blog). Retrieved 2020-12-14.

- ^ Moroz et al. 2018.

Bibliography

- Blinn, Jim (July 1997). "Floating Point Tricks". IEEE Computer Graphics & Applications. 17 (4): 80. doi:10.1109/38.595279.

- Blinn, Jim (2003). Jim Blinn's Corner: Notation, notation notation. Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN 1-55860-860-5.

- Eberly, David (2001). 3D Game Engine Design. Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN 978-1-55860-593-0.

- Goldberg, David (1991). "What every computer scientist should know about floating-point arithmetic". ACM Computing Surveys. 23 (1): 5–48. doi:10.1145/103162.103163. S2CID 222008826.

- Hardy, Godfrey (1908). A Course of Pure Mathematics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-72055-9.

- Hennessey, John; Patterson, David A. (1998). Computer Organization and Design (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers. ISBN 978-1-55860-491-9.

- Lomont, Chris (February 2003). "Fast Inverse Square Root" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-02-13.

- McEniry, Charles (August 2007). "The Mathematics Behind the Fast Inverse Square Root Function Code" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-11.

- Middendorf, Lars; Mühlbauer, Felix; Umlauf, George; Bodba, Christophe (June 1, 2007). "Embedded Vertex Shader in FPGA" (PDF). In Rettberg, Achin (ed.). Embedded System Design: Topics, Techniques and Trends. IFIP TC10 Working Conference:International Embedded Systems Symposium (IESS). et al. Irvine, California: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-72258-0_14. ISBN 978-0-387-72257-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-05-01.

- Striegel, Jason (2008-12-04). "Quake's fast inverse square root". Hackszine. O'Reilly Media. Archived from the original on 2009-02-15. Retrieved 2013-01-07.

- IEEE Computer Society (1985), 754-1985 - IEEE Standard for Binary Floating-Point Arithmetic, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers

- Moroz, Leonid V.; Walczyk, Cezary J.; Hrynchyshyn, Andriy; Holimath, Vijay; Cieslinski, Jan L. (January 2018). "Fast calculation of inverse square root with the use of magic constant analytical approach". Applied Mathematics and Computation. 316 (C). Elsevier Science Inc.: 245–255. arXiv:1603.04483. doi:10.1016/j.amc.2017.08.025. S2CID 7494112.

Further reading

- Kushner, David (August 2002). "The wizardry of Id". IEEE Spectrum. 39 (8): 42–47. doi:10.1109/MSPEC.2002.1021943.

External links

- 0x5f3759df, further investigations into accuracy and generalizability of the algorithm by Christian Plesner Hansen

- Origin of Quake3's Fast InvSqrt()

- Quake III Arena source code

- Implementation of InvSqrt in DESMOS

- "Fast Inverse Square Root — A Quake III Algorithm" (YouTube)

![{\displaystyle [1,254]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d801b7a8b6fe75d43aab5629d4f425d519f9ba82)